Spartacus

Spartacus (d. c. 71 BC) was a slave of Thracian origin, from the maidoi tribe, probably located in the Macedonian region of influence, which according to Greek and Roman sources, led a rebellion against the Roman Republic on Italian soil, which occurred between 73 and 71 BC. C., known by the name of the third servile war. This war raged across the entire peninsula for almost three years, and the events continued to have direct and indirect effects on Roman politics in subsequent years. Gladiators were slaves from the regions subdued by Rome, bought by merchants, who fought in combat in amphitheaters and arenas (coming to death on extraordinary occasions) for the entertainment of the Roman public. Espartaco, along with other gladiator slaves, devised an escape plan that triggered an outbreak throughout the peninsula. Fugitive slaves from everywhere joined them, thus forming an army that grew to approximately one hundred and twenty thousand people. Guided by Spartacus, they achieved a mixed armed force made up of men, women and children that, surprisingly, constituted a combination that repeatedly demonstrated its ability to resist and surpass the equipped and trained Roman army, the qualified legions. After numerous victories, and about to gain freedom by crossing the Alps, they returned to besiege Rome. The war finally culminated in 71 BC. c.

Origins

According to the references of the historian Plutarch, Spartacus was a Thracian, and properly Greek, according to the author. The Roman historians Apian and Florus agree on its origin. Thracian was also a type of Roman gladiator. Contemporary sources indicate that he came from the people of the maidoi (Greek Μαιδοι, «meadows»), with ancient Phrygian origin.

The maidoi lived along the southern Strymon River and the Nesto River (between Lake Kirkinis in Greece and the town of Sandanski), bordering on the macednoi. The geographical location determines that the maidoi lived within the region that is considered to have integrated the kingdom of Macedonia during the Hellenistic period (inherited from Philip II and Alexander the Great), by then a strongly Hellenized area, when the kingdom fell in 168 B.C. C. at the hands of Rome, renaming it Roman province of Macedonia (today southern Bulgaria, northern Greece and Albania).

All the known sources, very fragmentary, agree in describing Spartacus as a cultured man. Mostly the sources also agree in affirming that Spartacus came from a noble family, deducing that, according to Plutarch's writings, his wife was the prophetess of his people; normally the positions in the oracles were typical of the high strata. There is a story about a prophecy of the oracle of the Greek god Dionysus, who was worshiped by Spartacus, who predicted that he would be a liberator. The supposed noble origin is due to his nickname, since the name Spartacus was common in the princes and kings of the kingdoms in the region of Thrace and the Black Sea («Sparta», «Sparadokos»).

Apparently, when the people maedi were invaded by Rome, Spartacus was forced to join the auxiliary troops of Rome (auxilia), from which he deserted. Not being a Roman citizen, he was captured and reduced to slavery along with his wife, and by physical force he was bought by a merchant to fight in the Capuan gladiatorial school of Lentulus Batiatus.

Gladiator School

Seneca, a politician and senator to Nero and Claudius, wrote about gladiator fighting:

«By chance, at noon I attended an exhibition, waiting for some fun, some jokes, relax. But the opposite came out. These midday fighters come out without any armor, expose themselves without defense to blows, and no one strikes in vain. In the morning men cast the lions; at noon the gladiators to the spectators. The crowd demands that the victorious who has killed their opponents urge the man who, in turn, will kill him, and the last victorious reserve him for another massacre. Man, sacred to man, kill him for fun and laughter. »

In these schools, prisoners of war and convicted criminals—who were considered slaves—were trained in the skills necessary to fight to the death in gladiatorial games.

Rebellion and flight

In the year 73 B.C. C., during his stay at the gladiator school, Spartacus devised and carried out a rebellion in order to escape with two hundred companions. The plan was hatched by Spartacus, along with the Celts Casto and Canico and the Gauls Crixo and Enomao. They armed themselves with kitchen utensils and eluded the legions that intercepted them. Of the two hundred who started the rebellion, only 74 managed to escape, and some sources cite that a woman accompanied them, presumed to be a companion of Spartacus. escape strategists, for their warrior skills and possibly for their noble character (before being captured by Rome).

On the way they assaulted a convoy carrying gladiatorial weapons and seized it; then they took refuge on Mount Vesuvius, from where they began to carry out sabotage actions against neighboring towns. Spartacus established an equitable distribution of the loot among all his men, which attracted him a large number of followers among the slaves of the farms surrounding the volcano, which began the swelling of his forces.

The war, Spartacus' army and defeats of Rome

Upon learning of the mutiny, the Romans, without giving much importance to this incident, sent a small brigade of soldiers from Capua, which was defeated. The slaves quickly replaced their gladiator weapons with real Roman armor, which would cause confusion for the legions when facing an army of the same uniform as theirs.

Battle of Vesuvius

After this first defeat, the Romans sent a unit of three thousand men under the command of Gaius Claudius Glabro. Contrary to military doctrine, and underestimating ex-slaves, Claudio Glabro established his camp at the foot of the mountain, where the only path coming from the top descended, without establishing a protective fence. Upon learning of this fact, Spartacus adopted a brilliant plan: his men descended the steepest part of the volcano tied by ropes to the stump of a wild vine and fell by surprise on the Roman soldiers, causing numerous casualties and forcing the survivors to flee in disorder, leaving the camp, provisions, horses and weapons at the hands of the slaves. It was the first great victory of Spartacus, in what was later called the Battle of Vesuvius.

Organization of Spartacus' Army

After the Battle of Vesuvius, Spartacus and his companions Crixus and Oenomaus set about organizing a disciplined regular army that could successfully confront the powerful Roman legions. Among the slaves they had doctors, carpenters and priests. In this way the construction of weapons was prepared, and the infantry and cavalry were organized. With the constant influx of slaves from different parts of the empire, the slave legion managed to muster fifty to seventy thousand men. After the organization, a plan for future actions was drawn up: flee from Rome by marching north. As the slaves lacked military training, Spartacus's forces displayed some inventiveness in their use of locally available materials, which in turn resulted in their use of ingenious and unorthodox tactics when confronting disciplined Roman armies. rebels spent the winter of 73 B.C. C. arming and equipping his new recruits and expanding his territory of sabotage to include the cities of Nola, Nuceria, Turios and Metaponto.

Battles to the North

Although there is no precise information about it, it can be said that Spartacus' plan consisted of gathering as many rebels as possible and leaving Italy by crossing the Alps. This was the only possibility of freedom for most of them, since once out of Italy many rebels could escape to territories that had not yet been conquered by Rome (such as Germany).

The Romans sent against the rebels two legions brought from the northern border of Italy, under the command of the praetor Varinius. He tried to surround Spartacus with a pincer maneuver, for which he divided his forces into three parts. Spartacus, well informed by his spies, took advantage of the division of the Roman forces and separately defeated the two assistants of Varinius, and then attacked the forces commanded directly by him, reaching the point of capturing the praetor's lictors and his own horse, reason why Varinio had to flee on foot.

As a result, the rebel movement spread throughout southern Italy. Many cities were taken and sacked by the slaves. The Roman historian Salustio speaks of the disobedience of Spartacus, the massacre of the slaveholders, and the cruelties committed by former slaves against their former oppressors. Since it was impossible to wage a long war of attrition against the Roman Republic, since it was immensely rich and could rebuild its armed forces over and over again (using conscription and its allies), in order to escape, the plan began. to leave the peninsula, marching his troops north. Sometime during these events, or possibly during the winter raids of late 73 B.C. C., they lost their leader Oenomaus—perhaps in battle—and is no longer mentioned in the histories.

First separation of the slave army

At that precise moment, dissensions arose among the rebels, the result of which was the separation of a group of about twenty thousand men, made up mostly of Gauls and Germans, under the command of Crixus.

Apparently, according to what the Roman historian Sallust indicates, the dissensions were related to the plan of future actions: Spartacus wanted to get his men out of Italy, but Crixus and his men were determined to fight the Romans, defeat them and even take Rome, annihilating the oppressor. It is also possible that Crixus was also supported by the poorer strata of the free population who had joined the rebellion and who obviously had no intention of leaving Italy.

While Spartacus' troops headed north, Crixus and his army headed south to besiege Rome. Crixus did not have the strategic ability of Spartacus, and the propraetor Arrio (Gelio's assistant) intercepted and annihilated them in Apulia, Crixus himself falling in combat.

At first, consular armies were successful. Gelio's aide, the propraetor Arius, attacked a group of some thirty thousand slaves under Crixus near Mount Gargano, killing two-thirds of the rebels, including Crixus, with only one legion. historians, the slaves repulsed the legion's attack and after the victory they got drunk drinking wine to celebrate it. When the Romans returned, they found them drunk and massacred them.

Battle in the Apennine Mountains

Despite the separation of Crixus's forces, this did not weaken the slave army. His troops continued to be strengthened by the continuous influx of escaped slaves from all parts of Italy, to the point that Appian claimed that the army numbered one hundred and twenty thousand men in all. The Roman government, having noticed the constant defeats of its legions, took note of the seriousness of the danger and sent in 72 BC. To the armies of the consuls Lentulus and Gelius. Spartacus, with brilliant maneuvers in the passes of the Apennine mountains, inflicted a series of defeats on Lentulus, Gelius and Arius, avoiding ambushes set up by the Romans and continuing his advance northward. Spartacus engaged Lentulus's legion, defeated it, turned around, and destroyed Gelius's army, forcing the Roman legions to retreat in disarray. Appian claims that Spartacus executed some three hundred captured Roman soldiers to avenge Crixus' death., forcing them to fight each other to the death like gladiators.

Battle of Modena and return to the south

The defeated consular armies returned to Rome to regroup while Spartacus' followers moved north. The consuls again attacked Spartacus somewhere in the Picenus region, and again they were defeated.

The Romans became desperate when they saw that their legions established in Italy were not enough to defeat the rebels. However, they made one last attempt to prevent their departure from the Peninsula. The governor of the province of Cisalpine Gaul, the consul Gaius Cassius Longinus, gathered all available forces and awaited the arrival of Spartacus in the Po Valley, in the city of Modena. Spartacus accepted the battle proposed by the consul and defeated him, after which he was able to carry out his plan to cross the Alps, but instead he returned south.

Among classical historians, who wrote their accounts only a few years after the events themselves, there seemed to be a division over what Spartacus' motivations were. Apiano and Floro write that he intended to march on Rome itself.

Battle of Samnium and siege of Rome

Although there is no clear explanation of this matter, it can be concluded that at that moment the rebels were so enthusiastic about their string of victories that there was no question of escaping from Italy. They wished to culminate their revenge on him by taking Rome, and Spartacus was forced to submit lest he completely lose control of his undisciplined army.

Thus, Spartacus approached Rome. Knowing that he could not take the city given its powerful fortifications, he took a passive stance. The Romans, for their part, had entrusted the supreme command of the army to the praetor Marcus Licinius Crassus, awarding him the ten available legions, although they were not the best, since the soldiers were demoralized by the unprecedented victories of Spartacus.

According to Apiano, the battle between Gelio's legions and Crixus's men near Monte Gargano was the beginning of a long and complex series of military maneuvers that almost resulted in Spartacus's forces storming the same city from Rome.

With the two enemies approaching, Crassus ordered them to assume a defensive position while he worked out a strategy to defeat the rebels, which consisted of enclosing them in the mountainous Picenum region, while receiving more reinforcements. The battle was defined in the region of Samnio. However, one of his aides, Mummius, who had orders to go to a position more advanced than the one occupied by the rebels in order to surround them, opted instead to attack them directly, being defeated. During this battle, many legionaries threw down their weapons (as a sign of cowardice) and fled. After the victory, Spartacus continued his march towards the south.

In view of this defeat, Crassus decided to take severe measures to restore discipline among his troops. Those who fled before his enemies were decimated with the decimatio , a punishment that had not been used for a long time, and which consisted of condemning one in 10 of the deserters to death. He ordered his men to beat each of the condemned to death. As a consequence of this measure, no one else dared to violate the orders or tried to flee from the enemy.

March south and trade with merchants and pirates

Apian states that at this point Spartacus changed his intention to march on Rome—implying that this was Spartacus' objective after the confrontation at Picenus—because "he did not yet consider himself prepared for that kind of fight, since his force was not properly armed, and because no cities had joined him, only slaves, deserters, and rabble," and he decided to withdraw again to southern Italy. They besieged the city of Turios and the surrounding countryside, arming themselves, raiding the surrounding territories, trading the loot for bronze and iron with merchants (with whom to manufacture more weapons), and occasionally clashing with Roman forces, which were always defeated.

Crassus, having arrived from the north, and learned that the rebels were trying to cross into Sicily, took advantage of the opportunity to lock them up in the southwestern tip of the Italian peninsula. To this end he built from sea to sea a fortified line of about 65 km, composed of a deep moat and fences four and a half meters high. Spartacus resorted to a cunning tactic used by Hannibal against the Romans over a hundred years before. During one night he rounded up as many cattle as he could, put torches on their horns, and drove them over the fence. The Romans concentrated on the point where the torches were directed, but soon discovered, to their surprise, that they were not men, but cattle. The rebels, for their part, crossed the fence through another sector without being disturbed and returned to Lucania (present-day Basilicata), in the northern part of the Gulf of Taranto.

Meanwhile, Spartacus reached Campania and advancing further he reached the outskirts of the city of Turi, where many merchants appeared to obtain the loot taken by Spartacus. In need of material to build weapons, he forbade trade for lace, gold, or silver; the rebels only had to accept iron and copper, materials necessary to make weapons.

Spartacus and his army reached the Tyrrhenian Sea, in the area of Calabria. Here he came into contact with the Cilician pirates, who promised to give him a fleet to transport the rebel troops to Sicily in order to make the island an impregnable rebel stronghold, or simply flee by sea to other latitudes.

End of the war

The Senate lost faith in Crassus when they saw that he could not defeat the slaves. They then sent the general Gnaeus Pompey, recently arrived in Italy from Hispania, where he had recently suppressed the rebellion of Sertorius. Licinius Lucullus, Macedonian lieutenant, was ordered to disembark with his troops in the port of Brindisi from Greece.

The Senate's idea was to encircle the slaves from three fronts: northwest (Pompeius), southwest (Crassus), and east (Luculus). In total, the Romans would add about twenty legions (around one hundred and twenty thousand men), of which those of Pompey stood out, who returned from a victorious campaign in Hispania.

Second separation of the slave army

Spartacus attempted to negotiate with Crassus to end the conflict before Roman reinforcements arrived. When Crassus refused, a portion of Spartacus's forces broke out of confinement and fled into the mountains west of Petelia (present-day Strongoli), at Bruttium, with Crassus's legions in pursuit. The legions managed to catch up with a part of the rebels, cut off from the main army, killing over twelve thousand of them. However, Crassus's legions also suffered losses, as the fleeing slaves turned to face the Roman forces, initially defeating them, but were ultimately defeated.

Although at the beginning of the rebellion the separation of a similar group had not been of major importance, now the situation was completely different. Any weakening of the rebel forces would prove deadly, since there was no longer a reserve of slaves who could join them. In this way, Spartacus had about eighty thousand men left.

Finally, the slave troops moved south to Brindisi, possibly with the idea of crossing the Adriatic Sea and landing in Greece or Illyria. However, Espartaco wanted to do the test. Arriving near the city, his spies informed him that Lucullus was already there. He then stepped back to face Crassus and Pompey.

Battle of Silario River

In the year 71 B.C. C., in Apulia, the last battle was fought (called by some historians the battle of the Silario River). It is said that before it they took his horse to Spartacus, and he killed him with his sword, saying: "Victory will give me enough horses from among the enemies, and if I am defeated, I will no longer need them."[citation required]

Besieged in the south of the peninsula, and surrounded by the Roman armies, the rebels would be willing to sell their defeat dearly and never serve the Romans again, but they could not resist the superiority of the Roman legions. At the end of the battle, of the eighty thousand rebels, sixty thousand perished; instead the Romans only lost a thousand men; according to Roman sources, the body of Spartacus could not be located.

Survivors

The remnants of the rebel troops, approximately twenty thousand, dispersed. A certain number of them managed to flee and took refuge with the Cilician pirates, since the southern part of the Italian peninsula had an important commercial and fishing traffic. Pompey managed to destroy a troop of five thousand men who were heading north trying to leave Italy over the Alps, as was Spartacus's initial intention. The Romans took six thousand prisoners, who were crucified along the section of the Appian Way, between Capua and Rome.

Spartacus in art

Monuments

Novels

- Spartacus, novel by Rafael Giovagnoli (1874).

- The Gladiators, novel by Arthur Koestler (1940)

- Spartacus, novel by Howard Fast (1951)

- Spartacus: The Gladiator, novel by Ben Kane (2012)

- Spartacus: Rebelion, novel by Ben Kane (2012).

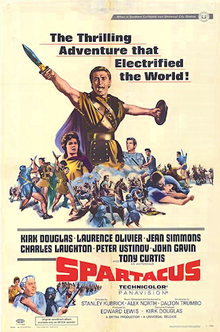

Cinema

- Spartaco (Sins of Rome), 1953 tape by director Riccardo Freda.

- SpartacusStanley Kubrick's film starring Kirk Douglas (1960).

- Spartacus and the ten gladiatorsNick Nostro (1964).

- Il gladiatore che sfidó L`imperio, tape by Domenico Paolella (1965).

Television

- Spartacus, Robert Dornhelm's television mini-series starring Goran Visnjic (2004).

- The Romans: Spartacus. The Rebellion of Slaves, novel by Max Gallo (2006).

- Spartacus: Blood and Sand (Spartac: Blood and Sand), Starz TV series created by Steven S. DeKnight and starring Andy Whitfield (2010).

- Spartacus: Gods of the Arena, prequel Spartacus: Blood and SandStarz chain. Starring Dustin Clare (2011).

- Spartacus: Vengeance, sequel Spartacus: Blood and Sand, of the Starz chain, starring Liam McIntyre (2012).

- Spartacus: War of the Damned, sequel Spartacus: Vengeance, of the Starz chain, starring Liam McIntyre (2013)

- Barbarians Rising, docudrama of the History Channel chain, starring Ben Batt (2016).

Ballets

- Spartacus, ballet of Aram Jachaturián (1956).

- Spartacus, ballet Bolshoi, Russia (2013).