Spanish medieval literature

- For the other literatures developed in the Peninsula during the Middle Ages, see: Medieval Galician Literature; Medieval Catalan Literature; Medieval Basque Literature; Medieval Spanish-Arab Literature; Hebrew Spanish Literature.

Medieval Spanish literature is understood as the manifestations of literary works written in medieval Castilian between, approximately, the beginning of the 13th century and the end of the 15th century. The works of reference for those dates are, on the one hand, the Cantar de mio Cid, whose oldest manuscript would be from 1207, and La Celestina, from 1499, the work of transition to the Renaissance.

Since, as demonstrated by the glosses used in Castile to explain or clarify Latin terms, towards the end of the 10th century spoken Latin had greatly distanced itself from its origins (beginning to give way to the different peninsular Romance languages), there are It must be understood that oral literature would be being produced in Spanish long before written literature.

This is demonstrated, on the other hand, by the fact that different authors between the mid-eleventh century and the end of the eleventh could include, at the end of their poems in Arabic or Hebrew, verses that in some cases constituted samples of traditional lyric in the Romance language, what is known as jarchas.

Introduction: the genres of medieval literature

Genres of Fiction

Literary composition in the Spanish language (and, in general, in the Romance language) was initially made in verse. There are two main reasons for this: on the one hand, its character as oral-popular literature (which implied its recitation with frequent musical accompaniment); on the other, that writing in prose required a tradition in the use of Spanish (especially for the consolidation of its syntax) which, given the cultured dominance of Latin until well into the Middle Ages, could not occur until the 13th century, when Alfonso X, el Sabio, decided to make Castilian a language of use both for the affairs of the administration of the kingdom, and for the composition of his historiographical and other types of works.

Thus, then, the first genres to consider are traditional lyric and epic poetry (cantares de gesta and romances), which, having been collected in writing from the xiii century, would be testimonies of oral compositions earlier in time; both genres make up what is called the minstrel mester literature, that is, literature composed to be recited. In addition, we must reckon with the primitive Castilian theater.

This theater seems to date back to the 11th century, in the form of representations related to religious themes. This is the case with the first theatrical text in Spanish, the Representación de los Reyes Magos, the only copy of which dates from the years in transit between the century. xii and xiii, and which, by language, can be dated to the middle of the xii. Subsequently, and until La Celestina (whose affiliation to the theatrical genre is debatable) the examples of theater in Spanish are always indirect, through references in other works.

Within the written genres, since the language of prestige for educated (or courtly) lyric during the Middle Ages was Galician-Portuguese, educated lyric in Spanish did not begin to be cultivated until the middle of the fourteenth century, appearing its most relevant figure, Jorge Manrique, in the 15th century.

As for the prose,

the earliest [prose] samples in Spanish or in another dialect linked to it date from the end of the century xii and the reign of Fernando III (1217-1252); they are historical documents and short legal texts.Pedraza Jiménez and Rodríguez Cáceres (2006, p. 31)

However, already in the same xii century, during the bishopric of Raymond, there is evidence that in the process of translating various works of various genres (mathematics, astronomy, medicine, philosophy...) into Latin, on many occasions the intermediate step of translating them orally into Spanish was taken: first from the original language to this and then, which is of singular importance, from Castilian to Latin; Such a process assumed that the Romance language was already fully constituted to express abstract ideas or high calculations.

But the full consolidation of Spanish as a written language at all levels occurred in the xiii century. On the one hand, this made possible the appearance of the works of the so-called mester de clerecía (narrative poetry in verse of a cultured type: Milagros de Nuestra Señora, by Berceo and Libro de buen amor, by Juan Ruiz) and on the other, along with the essays type works, of the first literary narrative works in prose: stories which, in principle, were translations/adaptations made by Alfonso X's workshop, and which already in the xiv century became original creations (although with an important popular background), either in the form of fictional adventure stories already close to the novel genre (Book of the Knight Zifar), or in the form of collections of short stories, as is the case of El conde Lucanor by don Juan Manuel.

Nonfiction Genres

Until well into the 13th century the languages of scholarship were Latin, Arabic, and Hebrew, in which everything was written. to do with religion, history and science. During the reign of Ferdinand III of Castile (1217-1252), Spanish gradually became a written-literary language.

As has been pointed out before, the origin of Spanish literature is in verse, and not in prose, because the technique of teaching the language was based on the imitation of classical literary texts, which were in verse. Later, when poetic techniques were consolidated and their expressive possibilities were fully developed (with the mester de clerecía), matters that were previously written in verse were transferred to the formal domain of prose.. This is also directly related to the maturation of the political and social system: prose, more difficult than verse, has a greater capacity to relate the different logical and dialectical units of human thought.

Thus, the content of the first works written in Castilian prose is mainly of a historical nature and they appear throughout the xii. In the first place, there are the Crónicas (c. 1186) of the General Charter of Navarre, brief narratives in the form of annals. Secondly, there are some brief Anales primeros toledanos (very impregnated with Mozarabisms). Later, the Liber regum (c. 1196-1209), originally in Navarro-Aragonese and translated into Spanish at the beginning of the xiii. There are also various contracts and diplomas, of a particular nature, which, when using Spanish, reflect the difficulties of understanding that written Latin posed, something that was manifested in the continuous use of glosses from the x.

Consequently, since the end of the xii century and for political reasons, legal norms have been established in writing in a language understandable to the majority: Spanish. And, little by little, certain narrative resources are being developed in legal texts: for example, the exempla or illustrative short stories of different cases. In addition, translations are very important in the development of prose in Spanish, which were started by Archbishop Raimundo in Toledo (with the so-called school of translators), since it was a very beneficial linguistic exercise., among other things, to make the Spanish syntax more flexible.

In spite of everything, the essential figure of the culture in Castilian of this time is Alfonso X; your activity

as a promoter and cultivator of science and lyrics is of extraordinary magnitude, since his name appears at the forefront of scientific treaties, legal works, historical compilations and poetic, lyrical and narrative compositions, of love and mockery, and religious songs.Alvar, Mainer and Navarro (2005, p. 102)

Both he and, later, his son Sancho IV, promoted as kings of Castilla y León the elaboration of a considerable number of works of very different essay genres.

Historiography

Alfonso X owes his greatest prestige to historiographical work; His production in this area is made up of two titles: the Estoria de España and the General Estoria .

Other works and authors linked to history are:

- La Fazienda de Ultramar

- A book of the first quarter of the century xiii which constitutes a geographical and historical route as a guide of pilgrims to the Holy Land;

- La Great conquest of Ultramar

- A story that contains a very novel chronicle of the conquest of Jerusalem during the First Crusade and dating from 1291 to 1295 in its first writing;

- The Victorial or Chronicle of But Child

- Written by Ensign Gutierre Díez de Games: he narrates the feats of this character, who handles his own story;

- La Embassy to Tamorlan

- In a medieval travel book written in 1406 by Ruy González de Clavijo, whose content is a relationship of the embassy that this author made, together with the Dominican Alfonso Páez de Santamaría, Samarkand before King Tamerlán;

- Fernán Pérez de Guzmán (1378-1460)

- Sobrino de Pero López de Ayala y señor de Batres: is the first author of portraits in Castilian literature, entitled Generations and semblances (1450); collects biographies of contemporary or near illustrious characters in time;

- Hernando del Pulgar (h.1430-1492)

- Chronist of Henry IV and the Catholic Kings, who writes another book of portraits: Males of Castile, imitation of the Generations and Semblanzas.

In particular, historiography in the xv century is led by Enrique de Villena (1384-1434). The most important text of his is The twelve labors of Hercules (1417), previously written in Catalan. It is a complex work in which, based on classical mythology and through an interpretive method, he exposes his vision of the society of his time. The production of Enrique de Villena was an innovation in Spanish prose, due to his erudition and restoration of the Latinized syntax —imitating Latin.

Religious works

Medieval works with religious content are basically from the 13th century, specifically those derived from the translation into Romance languages of the Bible and writing a doctrinal literature or catechisms.

Didactic works

The works aimed at teaching some type of knowledge materialized, first of all, in the so-called wisdom literature, which developed throughout the xiii century in the form of collections of sentences, either original or versions of originals in Arabic.

Within didactics, sermons should also be included, whose technique, given the supremacy of religious as literary authors, was enormously influential. There were two types of sermons: the cults (in Latin) and the popular ones, in the Romance language. This second, given the type of audience to which it was addressed (mixture of laymen and lawyers), abounded in the use of resources such as exempla (illustrative stories extracted from the Bible and other stories, real or fictitious). with moralizing purpose); In addition to the exempla, the sermons also used the sententiae, or sayings of famous men, originating in rhetoric and early Christianity.

In the middle of the xiii century, moralizing or didactic texts were translated from Arabic. Among them are the Book of Good Proverbs, the Golden Bites, the Book of One Hundred Chapters and the Flowers of Philosophy .

In the 14th century a singular work was also composed: the Moral Proverbs (1355-1360) by the Jew Santob of Carrion. Closely linked to Jewish teachings, the proverbs are dedicated to Pedro I of Castile and are written in seven-syllabic quatrains or Alexandrian diptychs with internal rhyme; its content expresses a very pessimistic moral relativism based on the contemplation of everyday life.

In addition to these collections of proverbs, in the Middle Ages there were also works intended for the education of princes and infants. To this tradition belong works transferred from Arabic such as Calila e Dimna, the Barlaam and Josaphat and the Sendebar, which although later were read as compilations of stories, had originally been conceived as texts for the indoctrination of princes.

A treatise by Alfonso Martínez de Toledo (1398-1468), chaplain to Juan II and Enrique IV, entitled The Archpriest of Talavera also belongs to doctrinal prose i> or El Corbacho.

Legal and legislative works

The textual practice linked to law has its first samples in Spanish with the fueros and the cartas pueblas, documents of specific scope in Castilla y León that, on the one hand, they tried to compile the privileges of each locality and, on the other, to legislate on the repopulation of the border lands.

The accession to the throne of Ferdinand III led to the search for unified legislation; The first step was the translation of Liber iudicum : the Fuero juzgo was thus established as a legal reference work for the territory conquered under his reign. The second step was already original, in the sense of starting a new legal corpus, the Setenario.

Alfonso X, for his part, not only finished the Setenario, but, relying on it, wrote the Siete partidas, a work that reflects his interest in imposing himself on their territories.

Scientific works

The concept of “the scientific” was very broad in the Middle Ages, and included astronomy, astrology, treatises on the properties of stones (The lapidary), plants and magic.

Alfonso X's interest in astrology put him in contact with Jewish and Arab scholars, from whom he took advantage of their Latin translations or commissioned new romanced versions. With them, he elaborates texts such as the Book of Knowledge of Astrology, a collection of treatises on astronomical topics, the Complete Book on the Judizios de las Estrellas, an adaptation of the treatise by Ali ibn ar-Rigal (Ali ben Ragel), or the Book of the Eighth Sphere. He also wrote treatises on measuring instruments or some astronomical tables , since his objective was to discover the future ( judicial astrology ). For this reason, he consulted his estrelleros when making decisions, which earned him the suspicion and distrust of clergymen and intriguing courtiers. He approached themes related to magic, in his Book of Forms and Images or in his version, partially preserved, of the Arabic Picatrix .

Lyric poetry

Popular lyrics

Medieval popular lyric comprises a varied tradition of compositions typical of the popular heritage, predominantly rural, used preferably during work and festivals, for which reason they were often songs associated with dance (there are also songs on the way, nursery rhymes, etc.). Thus, when considered as written texts, it must be borne in mind that under this version they appear as poetic texts isolated from their original artistic unit, which brought together lyrics and music.

Since the late 15th century many of these compositions were fixed verbatim and included in the great songbooks of the 15th and 16th centuries.

Popular Castilian lyric shares a series of elements that are a constant in the literary expression of different European traditions, which is why, for example, many of its texts are reminiscent of the Galician-Portuguese cantigas de amigo.

The contents, almost always linked to love (death for love, sorrow for separation, etc.), focus on reasons such as the description of the woman (for example, looking at her hair, often a symbol of virginity), the locations in natural settings where there is water (which symbolizes the date of love and eroticism) or flowers (also of sexual symbology), or with the presence of air or wind, symbols of loving communication.

On many occasions, the lyrical voice is a female voice, which laments before a confidante (generally the mother, sister, friend or nature) the distance from the loved one for reasons that include absence, loss or the duel.

Derived from these contents, it is possible to isolate a series of frequent themes in popular poetry: love and nature, intertwined and confused; the girl in love who does not want to be a nun; the praise of one's own beauty by the female lyrical voice; the rejection of marriage; the bad ones that cloud the love relationship; the hunt for love; etc

Formally, they are usually short compositions, from two to four verses of minor art (usually from six to eight syllables), irregular and with assonance rhyme. Given their oral roots, they are very rich in phonic resources (repetition of vowels, regular arrangement of accents, etc.) and parallelism.

As for its strophic form, there is a predominance of couplets, triplets, quatrains, etc. Sometimes, they present a gloss that develops or unfolds the chorus, with a more objective narration. The carol is the characteristic stanza: two or three verses, variable syllabically though preferably eight to six syllables, and with an abb rhyme scheme. It is estimated that they existed in Castile since the xiii century.

There are also examples of the zéjel, a poetic composition of Arabic origin, in the Cantigas of Alfonso X the Wise, in the Book of Good Love and in various cultured poets of the xv, such as Juan Álvarez Gato and Gómez Manrique.

Stylistically, the expression is simple and elemental, reflecting a naive and mysteriously irrational emotional attitude; there is an almost total absence of metaphors, preferring visual images that denote direct impressions of an external reality that is frequently subjectivized and loaded with ancestral symbolism; Finally, the expression of loving feelings is done openly, pathetically, with emphasis and repeatedly.

The cultured lyric

The so-called cult Castilian lyric is the poetry produced in the courts of the medieval kings Juan II of Castile, Enrique IV of Castile and the Catholic Monarchs by the knights who lived in them (kings, politicians, magnates...) and that has come down to us through the songbooks of the 15th century. It spans a century and a half, from the first poems of the Baena Songbook (c. 1370) to the second edition of the Geral Songbook (1516) by García de Resende. It can be considered as "the most impressive sample of courtly poetry in all of medieval Europe." The great educated Castilian poets of this time were Pero López de Ayala, the Marqués de Santillana, Juan de Mena and Jorge Manrique.

The most outstanding characteristics of cultured Castilian lyric are inherited from Galician-Portuguese lyric: fundamentally, the metrical terminology and the conception of courtly love (in which the goig or joy of Provencal love has been replaced by the coita or penalty).

This is an essentially social poetry, and not as subjective, intimate, as the traditional one. This social function is exemplified in the various topics covered: politics, morality, philosophy, theology, courtly love, etc. Unlike what happened in traditional lyric, cultured lyric no longer radically associates lyrics and music; Thus, the first lyrical compositions intended only for reading and not for singing appear, with which the composition had to respond to other needs and objectives: possibility of greater extension, search for new levels of meaning with allegory, fixation of genres (songs and Christmas carols), etc.

The stanzas begin to define themselves and focus in different ways, based on the eight syllable verse and the twelve syllable verse.

The themes of this poetry basically derive from the Provençal poetry of the Occitan troubadours: love and its variations. In the Peninsula some characteristics are added, such as allegories -characters based on abstract ideas-, complex puns, the lack of landscape and physical description, the lover's acceptance of misfortune, etc.

This poetry is usually collected in poetry books usually called songbooks. Three stand out:

- The Cancionero de Baena

- Collected towards the middle of the xv century for King John II of Castile.

- The Singer of Estúñiga

- Copyed in Italy, in the Court of Naples; includes poems by Juan de Mena or Iñigo López de Mendoza, Marquis de Santillana.

- The General Song

- Collected by Hernando del Castillo in Valencia, 1511, where there are poems by Fernán Pérez de Guzmán, Jorge Manrique, Florence Pinar, just the first Spanish poet, and those quoted above, Juan de Mena and Íñigo López de Mendoza.

To complete the panorama of poetry from this period, we can add other very diverse works in their form and genres:

- the Danzas de la muerte;

- the satirical poetrylike the Coplas de Mingo Revulgo or Coils of the baker;

- the poems of debate, which give dramatic form to the confrontation of two or more points of view on a topic. The oldest example of this kind of poem is Dispute of the soul and the body, compound, probably, at the end of the century xiiwhich is an adaptation of a French debate. Another important poem of this genre is Elena and Maria (on studs in the Middle Ages), but the masterpiece of the genre is the Reason for love with the nuns of water and wine, work whose theme is unclear: Christian allegory, literary formulation of a Cathar heresy, the need for reconciliation between opposites, etc.

- Hagiographic poems in octosyllables entitled Life of Saint Mary Egyptian and Book of the Childhood and Death of Jesustransmitted in the same manuscript of the century xiv in which the Book of Apollonius and copied, probably from an original in French, by an Aragonese scribe.

The narrative in verse

The epic. The epic songs

The epic is a narrative subgenre composed in verse and in the Romance language, whose origins date from the first third of the 11th century. Epic narratives are led by heroes who represent, by their values, an entire society; They tend to focus on relevant events in the history of a people, so these heroes end up being considered symbols for them.

It is also common for the plot of these stories to revolve around some problem of the protagonist with the social value of honor, which was the basis of the entire ethical-political system of vassal relations in the Middle Ages.

The Castilian epic takes its themes, fundamentally, from two historical events:

- The Arab invasion of the Peninsula and the first centers of Christian resistance (century VIII);

- The beginnings of the independence of Castile (century X).

In this sense,

the Spanish epic itself appears, even in its most ancient and indirect testimonies, characterized by an original theme (...) and by a vision of the world quite different from that of the gest chanson [French, previous in time]. The most important thing is that the rejection of "foreign history" does not only lead to seeking in the annals of one's own heritage matters worthy of becoming epic narratives, but above all to structure these narratives from an indigenous and independent cultural modelDeyermond (1991, María Luisa Meneghetti, "Chansons de geste y cantantees de gesta: la singularidad de la épica española", pp. 71-77 (73))

Thus, due to the influence of the French epic (through the Camino de Santiago and the presence of the Occitan world in the northeast of the peninsula), the Castilian epic only took some themes from it, such as the figure of Charlemagne, in the only text that shows traces of the so-called Carolingian cycle, the preserved fragment of the Cantar de Roncesvalles.

The epic poem is properly called cantar de gesta. It is said that the songs of deed are works that belong to the mester of minstrelsy, since they were transmitted and recited by heart by the minstrels who performed in town and city squares, in castles or in court rooms, to in exchange for a payment for your services. They knew how to dance, play instruments, recite and perform acrobatic and circus exercises. Consequently, the cantares de geste were represented with musical support before the public, making use of a monody: a slight final cadence in each of the verses that was underlined in the first and last of each run (intonation and conclusion).

The objective of this public recitation was twofold: to entertain and inform the audience, although without moralizing or pedagogical purposes (purposes that would be typical of the works of the mester de clerecía).

Very few have been preserved due to this oral transmission. In addition to the Cantar de mio Cid, which is almost complete, we have received fragments of the Cantar de Roncesvalles and the Cantar de las Mocedades de Rodrigo. News of other epic songs has reached us thanks to the historical chronicles, which used them as a source (for example, the Cantar de los seven infantes de Lara, which appears in the Segunda Crónica General —Crónica de 1344, by Pedro de Barcelos— and which is linked to the cycle of topics related to the Counts of Castile).

Some characteristics of the epic songs of Spanish literature are:

- His anonymous character.

- His great vitality, because his subjects survived in later literature (Roman, national comedy, neoclassical, romantic and modern drama, in the lyrics, in the novel, etc.)

- Their realism, because they were quoted in dates close to the facts they count, so there are hardly any fantastic elements.

The songs of deed were taken as historical documents on many occasions, because some were prosified and thus were included in medieval chronicles (such as the Estoria de España or First general chronicle of Alfonso X); Thanks to this, some have been partially preserved.

Sing of my Cid

The most important (and only complete) Spanish work of this genre is the Cantar de mio Cid, which is preserved in a 14th-century manuscript copy of a 1207 codex copied by Per Abbat de an original dated between 1195 and 1207. The date of writing the original is therefore close to 1200.

The work has been divided by modern editors into three songs:

- The first song deals with the banishment of the Cid by Alfonso VI, because of certain courteous intrigues. Martin Antolínez obtained from two Jews a loan of six hundred frames for the Cid, for his faithful and to keep his wife and daughters in the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña. The Champion conquers Castejón and Alcocer, populations that return the Moors in exchange for a ransom. Close the singing a confrontation with the Count of Barcelona.

- The second song starts with the siege and conquest of Valencia. Álvar Fáñez is present to the king and asks him to advise Doña Ximena and his daughters to leave the monastery to settle in Valencia. King Alfonso proposes to marry the daughters of the Cid with Fernán and Diego, infants of Carrion, to what he accesses. There are views on the banks of the Tagus and weddings with their parties in Valencia.

- The third song opens with the episode of the lion, of a novel character: while the Cid sleeps, it escapes from the net its lion, causing panic among the infants of Carrion, who, after confirming their cowardice in the battle against the Búcar king of Morocco, decide to return with their women to their palent lands. In Corps oakdal they are beaten and abandoned, for they are considered improper of their social condition. The Cid reminds the king that, being he who married them, it is his affront. Alfonso summons Cortes in Toledo, where the Cid regains his assets and lets But Bermúdez, Martín Antolínez and Muño Gustioz defeat, respectively, the Fernán and Diego infants and his brother, Asur González. His daughters recover the honor by marrying the infants of Navarre and Aragon.

The hemistiches oscillate between three and eleven syllables, with a clear predominance, in this order, of heptasyllables, eight syllables and hexasyllables, which gives verses of variable length between 14 and 16 metric syllables, and these are organized in series or runs of an indefinite number of verses that are assonant with each other.

Formulas —groups of words that are repeated with slight variations— appear systematically throughout the poem. This points to the oral nature of this genre, since at the origin of epic poetry, it would facilitate improvisation and memorization of verses. Among these formulas, the omission of verbs to say —said, asked, answered...— and epithets, adjectives generally applied to positively characterized people or places, stand out.

The Romance

The word romancero, in the context of medieval literature, refers to the set or corpus of poems called romances that have been preserved either in writing or through oral tradition. Composed anonymously from the 14th century, they were collected in writing in the 15th and make up what is called old ballads, as opposed to the new ballads, with already recognized authors, composed from the xvi. Spanish Renaissance musicians used some as text for their compositions.

The ballads derive, quite probably, from the epic songs: given the attitudes and demands of the public, the minstrels and reciters should have begun to highlight certain episodes of those songs that stood out for their interest and uniqueness; by isolating them from the whole of singing, romances would be created. This essential character of the same, led to them being sung to the sound of instruments in group dances or in meetings for entertainment or common work.

Formally, these are non-strophic poems of an epic-lyrical nature; This means that, apart from being narratives like epic songs, they present certain aspects that bring them closer to lyrical poetry, such as the frequent appearance of emotional subjectivity.

Driving from the epic, the verses are long, between 14 and 16 syllables, and with assonance rhyme; These verses present what is called internal caesura, in a very marked way, which tends to divide them into two parts or hemistiches with a certain syntactic independence. In the evolution of the genre, these hemistiches were gaining even more autonomy, which is why they were fixed at approximately eight syllables. Hence, on occasions, and due to the influence of lyric poetry that always used short verses, the romances appeared as runs of eight-syllable verses with assonance rhyme only in even verses.

Their themes and nature are very varied. An important group —perhaps the oldest— belongs to the epic genre and could be derived from fragmented epic songs that are almost entirely lost today. Another considerable part is made up of lyrical romances of very diverse characters or situations.

There are various proposals for thematic classification; However, there are constant categories that would be the following:

- Historical romances

- they deal with matters and events based on history; they are characteristic of the border problems between the Christian and Muslim kingdoms, and those focused on King Peter I of Castile. The calls of the French theme, the carolings (which count the exploits of Carlomagno and other characters of his court) and the Bretons (which gather the legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table);

- Epic and legendary Romances

- their themes come directly from legends or gestation songs; that is, it is stories already known poetically reworked, retaining as the only historical memory of certain characters;

- Adventure romances or novels

- They are entirely invented and feature folkloric, adventurous, loving, symbolic, lyric traits. Lovely feeling appears in its most varied manifestations: from eroticism to somber conjugal tragedy.

Stylistically, they are usually classified as:

- Traditional Romances

- Those in whom the action is presented in a rather dialogued way; precisely for that reason, they are also known by the name of romances-scene. The action is narrated almost always in present time, so the public is not as much a listener as a spectator and witness to some facts;

- Romances jugularcos

- Those whose narration is more delayed and thorough, focusing on an episode in a very intense way.

Other literary features are:

- Structurally

- They are characterised by their fragmentation: they do not tell complete stories, but they seek essentiality and intensity, beginning ex-abrupt and ending abruptly, with open endings: the story that counts on them lacks background and consequences; they are self-sufficient stories in which only the fundamental characters appear;

- Linguistics

- They are prone to expressive naturality, to spontaneity, to basic lexicon, to short sentences, to the use of few links and to prefer juxtaposition, to the elimination of space-temporal references, to the use of expressive intensifiers (intersections, exclamations, apostrophes, hypterals...) and to manage resources such as personification,;

- Narratively

- They present various lyric elements through the narrative. The narrator is usually neutral and encourages the intervention of the characters, introduced in direct style without verbum saydi. Lirism is manifested in the sharp tendency to present a mysterious and enigmatic view of reality, with the ability to become symbolic a detail and to make it the axis of romance. The alternation of verbal times, as was the case in the gestation songs, serves to capture the listener's attention: the historical present is used to bring and update the narrative, while the indefinite for climatic or climatic moments; the imperfect, on the other hand, is used to introduce the courtesy nuances or to project things and facts to the spheres of irreality. Finally, formulas and motifs also characteristic of epic appear.

The seventeenth century admired these compositions and did not hesitate to imitate and revitalize them. Authors such as Lope de Vega, Góngora or Quevedo wrote ballads in the manner of the ancients, forming what is now known as the New Ballads.

The Mester of Clergy

The mester de clerecía refers to the literary technique (a way of composing literary texts) developed in the 13th century by a series of writers linked to the university and scholarship (the clerecía ), and that they applied to the creation of narrative works in verse.

At the beginning of the xiii century, the vernacular languages of the peninsula, and specifically Spanish, had reached a relatively high degree of maturity. Thus, after a phase dedicated to the study of its grammar, on the basis of Latin, the clerics, who knew French as well, were able to elevate Castilian to the rank of a literary language, that is, a cultured language, suitable for writing all kinds of works. On the other hand, around 1200 the majority of the population no longer understood Latin. In these circumstances, it must have seemed useless to continue using a language only understood by a minority in works that, due to the interest of their historical, didactic, moral or religious content, should be known and understood by all.

The literary model that served as a point of reference for these writers was the Alexandre's Book, especially with regard to the use of the stanza that characterizes their works: the rib via. All in all, the Alexandre is a free adaptation into Spanish of the Alexandreis (c. 1182), a Latin work by the Frenchman Gautier de Châtillon, which served as school reading in the first Spanish universities; hence the strong imprint of Latin prosody in the Alexandre and, for example, the proscription of the sinalefa to force a careful and slow reading of the text, a general characteristic of the works of the mester .

Summarily, the defining features of the works of the mester de clerecía would be the following:

- They are written works to be read, not to be recited (as was the case with the works of the mester of play); his audience was normally worshipped: monks, schoolchildren, priests, etc.

- A culte and regular versification, manifested in the strophic form called cuaderna vía (four monolith verses of fourteen syllables each).

- use of a language very influenced by Latin, with a very cult style, with plenty of rhetoric figures.

- A didactic and moralizing attitude in the treatment of subjects.

- The arguments are linked to four major thematic groups: that of the miracles made by the Virgin (Miracles of Our Lady); that of the life of the saints; that of the accounts more or less free (Book of Alexandreand the and punishment of wise men.

The most important works of the mester de clerecía are Miracles of Our Lady, by Gonzalo de Berceo, and The Book of Good Love, by Juan Ruiz, Archpriest of Hita. Other relevant works are The Book of Alexandre and The Book of Apolonio and Rimado de Palacio.

Miracles of Our Lady

This is a narrative work in verse composed of a prologue and 25 independent stories that deal with two miracles performed by the Virgin. They are not entirely original stories by Berceo, since what he does is follow what is written in a Latin manuscript that he recreates.

The intention of the work is to present a set of moral examples, but above all it is a literary and doctrinal treatise on the Virgin Mary, in which, above all, her character as mediator of all graces stands out.

Book of good love

Also known by the title Book of the Archpriest, it is an autobiographical narrative in verse, from the second quarter of the xiv century. It is basically about love.

With the excuse of the story of his own love affairs, almost always frustrated, the narrator intends, ultimately, to warn and advise the reader or listener about the danger of the sins of the flesh.

All in all, the book presents a very heterogeneous structure: not only is it inspired by cultured (Latin) and popular traditions at the same time, but it alternates narrative parts with other didactic, proverbial and lyrical ones, and goes from humorous to moralizing tone continuously.

Its interpretation is controversial among specialists.

Prose Fiction Narrative

Prose in Spanish began with genres of a didactic or moralizing nature. Fictional prose in Spanish arose in the middle of the xiii century, although at that time it was about works whose models went back to the Eastern world, although not always.

These are collections of short stories or compilations of exempla such as the Calila and Dimna (the first vernacular collection, based on a Hindu collection of animal fables) and Book of the deceptions and the assayamientos de las mujeres, known as Sendebar (whose original title could have been The assayamientos de las mujeres).

Later, after the time of Alfonso X, prose, benefiting from the prestige acquired in works, especially historiographical ones, began to appear as a tool for composing novels. In this way, the novelistic works of the Middle Ages are transformations of historiography, as evidenced by the fact that their first samples are free adaptations of themes from antiquity considered historical.

The medieval novel is, all of it, of historical (or pseudo-historical) theme, since all the narratives are welcomed as accounts of facts actually occurred.Alvar, Mainer and Navarro (2005, p. 206)

So, at the beginning, the characters are always individuals of royal or similar dignity, gradually opening up to other social sectors, but always showing a preference for characters with attractive features. Consequently, the chivalrous novel becomes the most abundant narrative genre of the Middle Ages.

In the group of novels with a more historical content, The Great Conquest of Overseas stands out, about the crusades of the xi century (and in which the famous story of the Knight of the Swan appears).

The 14th century opens with the Libro del cavallero Çifar, the first Hispanic book of chivalry. Its elaboration began in the time of Sancho IV and its structure was enriched throughout the xiv century. It begins as an adaptation of the life of Saint Eustace, on which various elements are assembled. The writing that has come down to us consists of two prologues and four parts. The first two parts—"The Knight of God" and "The King of Chin"—follow a story of the separation and reunion of the members of a family. Collections of examples and sentences are interwoven in them. The third part, entitled "Punishments of the King of Mentón", includes the advice that Zifar —already King of Mentón— gives his sons Garfin and Roboán. The fourth tells the story of Roboam from the time he leaves the kingdom of Menton until he manages to be crowned emperor.

The increased presence of amorous episodes in chivalric novels resulted in the appearance, between the mid-century xv and 1548, of the genre of sentimental fiction. Even having chivalrous stories as a background, the atmosphere now is the same as that reflected in song poetry: courtly life. The plots are usually double, and focus on the separation of the lovers; resources tending to confer credibility to what is narrated abound in these novels, especially autobiography and the use of the direct speech of the characters (letters, interventions...). All these features are fixed in the novel by Juan Rodríguez del Padrón, Siervo libre de amor, and in the masterpiece of the genre, Cárcel de amor (c. 1488). by Diego de San Pedro.

Galician Juan Rodríguez del Padrón was born at the end of the 14th century and traveled throughout Europe, before taking the Franciscan habit in 1441 in Jerusalem. The first of his works is the most important, for inaugurating the new genre of sentimental fiction , which will culminate at the end of the century: it is about the Free Servant of Love (1439). With a Latin style, he narrates, in the first part of it, how the beloved despises the lover for confiding her passion to a false friend of hers. The Understanding, an allegorical character, in the second part dissuades the protagonist from the idea of suicide and introduces the Estoria de dos amadores —tragic love of Ardanlier and Liesa, which ends with the death of both. A third part is established in which the author, alone and desperate for love, finds a strange ship that awaits him.

Sentimental fiction reaches its greatest success with Diego de San Pedro and his Cárcel de amor. The plot is as follows: Leriano gets from the Author that Princess Laureola reciprocates his love by answering his letter. Denounced to her father, the king, Laureola is sentenced to death and saved by Leriano, who, seeing her love rejected from her, kills himself by drinking Laureola's letters dissolved in poison.

To the chancellor of Castile, Pero López de Ayala (1332-1407), we owe the Chronicle of King Don Pedro, which was followed by those of Enrique II, Juan I and Henry III. They are narratives that present characters and situations experienced by him, with points of view and justifications for his attitude that are not always clear to him.

Lastly, at the end of the 15th century the dialogue novel La Celestina appeared, a transitional work towards the Renaissance.

Don Juan Manuel

Don Juan Manuel (1282-1348), nephew of Alfonso X, is the prose writer with the most personality of the xiv century >.

He must have written his first book between 1320 and 1324: it is the Abbreviated Chronicle, a summary of one of the derivatives of those of Alfonso X. The Book of States, written between 1327 and 1332, it is an outlet for his worries and bitterness. In it he exposes the political and social reality of his time.

His best-known work is the Libro de los enxiemplos del Conde Lucanor e de Patronio, composed in 1335. It consists of two prologues and five parts, the first of which is the most famous for its fifty-one examples or stories, taken from various sources: Arabic, Latin or Castilian chronicles.

All the narratives in this first part have the same structure:

- Introduction: Count Lucanor has a problem and asks advice to Patronio.

- Nucleus: Patronius tells a story that resembles the problem raised.

- Application: Patronio advises the proper way to solve the problem, in relation to the narrated story.

- Moraleja: It ends with two verses in which the author summarizes the teaching of the narrative.

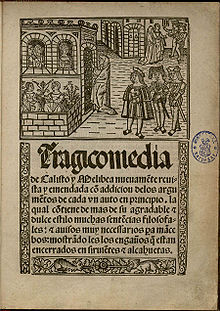

La Celestina

La Celestina is the title by which the Comedy or Tragicomedia of Calisto and Melibea is known, which was published in two different versions: one in 1499, which it consisted of 16 acts; and another, in 1508, which is 21. It belongs to the genre of humanistic comedy, a genre inspired by Latin comedy, which was intended to be read and not represented.

The author is Fernando de Rojas, born in La Puebla de Montalbán (Toledo), around 1475, from a Converso family (Jews converted to Christianity), who studied law in Salamanca and was mayor of Talavera de la Reina. He died in 1541.

The play tells how Calisto, a young nobleman, enters a garden to recover his lost falcon, and there he meets Melibea, with whom he falls in love and who initially rejects him. Calisto, on the advice of his servant Sempronio, hires Celestina's services to achieve the girl's favors. She manages with her tricks to make an appointment between Calisto and Melibea and, as a reward, she receives a gold chain from the lover. Sempronio and Pármeno, Calisto's servants and Celestina's business partners, claim his share. The old woman refuses to share her and they both murder her, a crime for which they are executed. Her companions, Elicia and Areúsa, decide to take revenge for what happened to the lovers by hiring Centurio. One night, while Calisto was with Melibea, upon hearing the noises caused by Centurio and his companions, the lover slips from a ladder and dies. Desperate, Melibea throws herself into the void from a tower in the house of her father, Pleberio, who closes the play with a lament for her dead daughter.

The most striking feature of the work is its realism, when portraying the bourgeois environment and the crisis of heroic and religious ideals in the face of the importance that money acquires.

As Fernando de Rojas declares in the two prologues of the work, its theme is to warn against the corruption caused by bad and flattering servants and against the evils caused by profane love; on the other hand, on a higher plane, the theme is the conception of life as a struggle in the manner of Heraclitus: "All things are created by way of contention or battle". Hence, the social classes of lords and servants, the sexes and even language itself, which on the one hand abounds in popular traits (exclamations, patrimonial words, proverbs, short phrases, diminutives, loose syntax) and on the other another in cultured and courteous traits (engoladas and latinizantes expressions, cultisms, sentences and apothegmas of well-known author, long periods, hyperbaton).

The Celestinesque characters also show a perfect characterization and the author usually groups them in pairs to better build their psychology by contrast: the servants Pármeno (young and still idealistic) and Sempronio (older and cynical); Tristán and Sosia, the servants who replace them; the prostitutes Elicia and Areusa, one more independent than the other; the privileged Calisto and Melibea, Pleberio and Alisa... Only two characters appear more or less isolated: Celestina, who represents the subversion of sexual pleasure, and Melibea's maid, Lucrecia, who embodies repression and resentment.

Melibea is an energetic woman who makes her own decisions. She is arrogant, passionate, adept at improvising, and strong-willed.

Calisto shows a weak character, who forgets his obligations and only thinks of himself and his sexual interest in Melibea.

Celestina presents herself as a vital person, fundamentally driven by greed.

The servants are not faithful to their master and seek their own benefit as well. This attitude is shown by Sempronio from the beginning and Pármeno once his warnings about Celestina are despised by Calisto and Celestina corrupts him with the help of one of her pupils.

The language is also displayed with full realism. Thus, cultured language (full of rhetorical figures, especially antitheses and geminations, hyperbaton, homoteleuton, cultism, etc.) and vulgar language (full of obscenities, profanity, threats, sayings, etc.) are used. Each character uses the language level that is their own. Celestina will use the one that interests her the most depending on the character she talks to.

Medieval theater

The Castilian medieval theater has confused, scant and irregular testimonies, to the point of doubting its existence until the end of the xv century.

- Of the Second half of the century xii We consider the first example of Spanish theatre. It's the Auto de los Reyes Magosfrom Toledo Cathedral. The language of the fragment is uncertain and points to a possible French source.

- More texts of theatrical representations than other literary genres are likely to have been lost in the Peninsula. Some laws of Alfonso X or rules of ecclesiastical synods point to imprecise dramatic manifestations, carried out by different forms of play.

- Till end of the century xv, he will not publish his representations who consider himself the father of the Spanish theatre: Juan del Encina (1469-1529). The structure of his works will be complicated as he acquires a greater mastery in the genre. Fundamental — in terms of learning new techniques — is their journey to Rome in 1499. His last work is the most ambitious. Egloga de Plácida y Vitoriano.

- Compañero, rival and admirer of his would also be the Salmantino Lucas Fernández (1474-1542), whose work is difficult to date, although it is supposed to be made around 1500. The edition of yours Lighthouses and eglogas appears in 1514 in Salamanca. This author shares budgets close to those of Juan del Encina, but prolongs the extension and number of characters.

- Many of the cars that had to be represented over the century may have been lost xv. A codex of the second half of the century xvi, called Codex of Old Cars It retains numerous works, represented in many different places of the Peninsula, which could be reworked by these medieval texts.

Contenido relacionado

1963

Bolivian history

Golden age