Spanish Language

Spanish or Castilian is a Romance language derived from spoken Latin, belonging to the Indo-European language family. It is part of the Iberian group and is originally from Castile, a medieval kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula. It is also informally known as "castilla", in some rural and indigenous areas of America, as Spanish began to be taught shortly after the incorporation of the new territories into the Crown of Castile.

It is the second language in the world by the number of native speakers (approximately 475 million) after Mandarin Chinese, and the third language in terms of speakers after English and Mandarin Chinese. Some 496.6 million people speak it as a first or second language with native proficiency, reaching 595.9 million when including speakers with limited proficiency, among whom there are 23.7 million learners. Thus, it can be considered the third language in international communication after English and French. Spanish has the third literate population in the world (5.47% of the total), being the third most used language for the production of information in the media, as well as the third language with more Internet users, after Chinese and English, with some 364 million users, which represents 7.9% of the total. It is estimated that by the year 2050 the Spanish language will have 820 million speakers, and 1,200 billion by the year 2100.

The language is spoken mainly in Spain and Latin America, as well as among Spanish-speaking communities residing in other countries, especially the United States with more than 40 million Spanish speakers. In some countries formerly under Spanish rule where Spanish is no longer the majority or official language of speech, it continues to hold great importance in the cultural, historical and often linguistic sense, as is the case in the Philippines and some Caribbean islands. In Equatorial Guinea, where it is an official language, it is spoken as a mother tongue by only a small part of the population.

It is one of the six official languages of the United Nations Organization. It is also an official language in several of the main international organizations - the European Union, the African Union, the Organization of American States, the Organization of Ibero-American States, the North American Free Trade Agreement, the Union of South American Nations, the Caribbean Community, the African, Caribbean and Pacific States and the Antarctic Treaty, among others― and in the sports field, FIBA, FIFA, the International Association of Athletics Federations, etc.

Spanish, like other Romance languages, is the result of centuries of evolution from spoken Latin (called Vulgar Latin) since the 17th century III approximately. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the Vulgar Latin of Roman Hispania gradually transformed and diverged from the other variants of Latin that were spoken in other provinces of the old Empire. The transformations gave rise, after a slow evolution, to the different Romance languages that exist today.

Historical, social and cultural aspects

Language name

Etymology

According to the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE), the word español comes from the Provencal espaignol, and this from the medieval Latin Hispaniolus, which means "from Hispania" (Spain).

The Latin form HĬSPĀNĬOLUS comes from the Latin name of the province of HĬSPĀNĬA, which included the Iberian Peninsula, rather from its ultra-correct form. It should be remembered that in late Latin the /H/ was not pronounced. The opening of the short Latin /Ĭ/ in /e/ would therefore have given in Proto-Romance: ESPAŇOL(U).

Another hypothesis holds that español comes from the Occitan espaignon. Menéndez Pidal offers another etymological explanation: the classic hispanus or hispánicus took the suffix -one in Vulgar Latin (as in Burgundian, Breton, Frisian, Lappish, Saxon, etc.) and from *hispanione it became Spanish old to spanish, “later dissimilarizing the two nasals we got to Spanish, with the ending -ol, which is not used to mean nations”.

The other denomination, castellano, comes from the Latin castellanus, which means of Castile, a medieval kingdom located in the central part of the Iberian Peninsula and origin of this language.

Controversy around «Spanish» or «Castilian»

The controversy surrounding the terms «Spanish» and «Castilian» is based on whether it is more appropriate to name the language spoken in Latin America, Spain and other Spanish-speaking areas with one or the other term, or if both are forms perfectly synonymous and acceptable.

Like many of the controversies related to the name of a language identifiable with a certain territory (Spanish with Spain, and Castilian with Castile, the ancient kingdom from which the language arose and began to be taught in America), or which leads coupled with an ideology or a historical past that provokes rejection, or that implies a fight in favor of a single denomination to facilitate its international identification and the location of productions in said language (for example, in computer networks), the controversy is extralinguistic.

From a strictly linguistic point of view, it is not possible to justify preferences for one denomination or another.

In the regulatory or prescriptive field, according to the regulations established by the main linguistic policy bodies of the Spanish-speaking area regarding the codification of the language standard (Royal Spanish Academy and Association of Spanish Language Academies), «Castilian» and «Spanish» are synonymous terms, although the Diccionario panhispánico de dudas, the work of this same normative institution, states: «The term Spanish is more recommendable because it lacks ambiguity, since it refers unequivocally to the language spoken today by nearly four hundred million people. It is also the name used internationally (Spanish, espagnol, Spanisch, spagnolo, etc.)».

Likewise, the normative dictionary edited by the Royal Spanish Academy and the Association of Spanish Language Academies is entitled Dictionary of the Spanish language.

Certain authors have shown their preference for one term or another, such as the Venezuelan linguist Andrés Bello, who titled his main work Gramática de la lengua castellana, or the Valencian Gregorio Mayans, who wrote, in 1737, in his book Origins of the Spanish language the following:

By "Spanish language" I understand that language that we usually speak all Spaniards when we want to be perfectly understood by one another.

On the other hand, the Spanish Constitution of 1978, in its third article, uses the specific denomination of «Castilian» for the language, differentiating it from the other «Spanish languages» that also exist, such as Euskera, Aragonese, Catalan or Valencian, Astur-Leonese, Galician or Aranese.

As for philologists, some authors justify the preferential use of one term or another based on its origin and historical evolution, interpreted in different ways.

Current position of the RAE

The RAE currently prefers the use of the term «Spanish» instead of the term «Castilian», despite considering both valid to refer to the official name of the language; although it also considers Castilian a dialect of the Spanish spoken in the Spanish region of Castilla. However, it should be mentioned that, when the RAE was founded in 1713, taking the French and Italian academies as a model, it set itself as an essential objective the elaboration of a dictionary of the Castilian language, «the most copious that could be made ». That purpose became a reality with the publication of the Dictionary of authorities, edited in six volumes, between 1726 and 1739.

SPANISH. To designate the common language of Spain and many nations of America, and which is also spoken as their own in other parts of the world, the terms are valid Spanish and Spanish. The polemic on which of these denominations is most appropriate is now overcome. The term Spanish It is more recommended for lack of ambiguity, as it refers in a univocal way to the language spoken today by more than four hundred million people. It is also the denomination used internationally (Spanish, espagnol, Spanisch, spagnoloetc.). Even being also synonymous with Spanish, it is preferable to reserve the Spanish term to refer to the Romanesque dialect born in the Kingdom of Castile during the Middle Ages, or to the Spanish dialect currently spoken in this region. In Spain, the name is also used Spanish when reference is made to the common language of the State in relation to the other co-official languages in their respective autonomous territories, such as Catalan, Galician or Basque.Pan-Hispanic dictionary of doubts2005, pp. 271-272.

History

The history of the Spanish language begins with the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, specifically with that of the central area of Hispania. After the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century century, the influence of learned Latin on the common people gradually diminished. The spoken Latin of that time was the ferment of the Hispanic romance varieties, the origin of the Spanish language. In the VIII century, the Muslim invasion of the Iberian Peninsula led to the formation of two distinct areas. In al-Andalus, the Romance dialects included with the term Mozarabic were spoken, as well as the languages of the invading minority (Arabic and Berber). Meanwhile, in the area where the Christian kingdoms were formed a few years after the beginning of Muslim domination, a divergent evolution continued, in which various Romance modalities emerged: the Catalan, the Navarro-Aragonese, the Castilian, the Asturian Leonese and Galician-Portuguese.

From the end of the XI century is when a process of assimilation or linguistic leveling begins, mainly between dialects Central Romanesque styles of the Iberian Peninsula: Asturian-Leonese, Castilian and Navarre-Aragonese, but also from the rest. This process is what will result in the formation of a common Spanish language, Spanish. More and more philologists defend this theory (Ridruejo, Penny, Tuten, Fernández-Ordóñez). The weight of the Mozarabic of Toledo, the city in which written Castilian began its normalization, has also been highlighted. However, other philologists continue to defend the Pidalian postulates of the predominance of the Castilian dialect in the formation of Spanish and its expansion through a process of Castilianization throughout the rest of the peninsular territories.

The Castilian Romanesque dialect, one of the precursors of the Spanish language, is traditionally considered to originate in the medieval county of Castilla (south of Cantabria and north of Burgos), with possible Basque and Visigothic influence. The oldest texts that contain features and words similar to Spanish are the documents written in Latin and known as Cartularios de Valpuesta, preserved in the church of Santa María de Valpuesta (Burgos), a set of texts that constitute copies of documents, some written as early as the IX century. The director of the Castilian and Leonese Language Institute concluded that:

"that Latin "was so far away from righteousness, was so evolved or corrupted...

It can be concluded that the tongue of the bulls of Valpuesta is a Latin language astounded by a living tongue, from the street and that it is clogged in these writings.”

The Emilian Glosses of the late X century or early XI, preserved in the Yuso Monastery in San Millán de la Cogolla (La Rioja), were considered by Ramón Menéndez Pidal as the oldest testimony of the Spanish language. However, there are later theories that affirm that these documents correspond to the Navarro-Aragonese romance, not the Castilian romance.

A decisive moment in the consolidation of the Spanish language occurred during the reign of Alfonso X of Castile (1252-1284). If the songs of deed were written in that vulgar language ―Castilian ―and for this very reason they were popular, it could be thought that the learned and literary works produced in the Toledo Court of the aforementioned king should be written in Latin, the only learned language that all of Christian Europe had admitted up to that time; That is why the fact that Alfonso X the Wise decided to direct a good number of works of high culture written in a language until then rejected by literate people for considering it too prosaic was a true cultural revolution. This gave rise to the official recognition of Spanish, which could alternate from then on with Latin, a language respected by all enlightened people.

Spanish spread throughout the peninsula during the Late Middle Ages due to the continuous expansion of the Christian kingdoms in this period, in the so-called Reconquista. The incorporation into the Crown of Castile of the kingdoms of León and Galicia with Ferdinand III of Castile and the introduction of a Castilian dynasty in the Crown of Aragon with Ferdinand I of Aragon in 1410 and later, the union end of the peninsula with the Catholic Monarchs increased assimilation and linguistic leveling between the dialects of the different kingdoms.

The first printed book in Spanish was published around 1472. By the 15th century, the common language of Spanish had become Introduced to a large part of the Iberian Peninsula. In 1492 the Sevillian Antonio de Nebrija published in Salamanca his Grammatica, the first treatise on grammar of the Spanish language, and the first published "in mold" of a modern European language. "Reglas de ortografía en la lengua castellana", printed in Alcalá de Henares in 1517, in which orthography is postulated as a one-to-one relationship between pronunciation and writing.

It is estimated that in the middle of the XVI century 80% of Spaniards spoke Spanish. The consonant readjustment began, which meant the reduction of the phonemic system by going from six sibilant consonants to only two or three, depending on the variety, due to the loss of sonority.

The colonization of America, which began in the XVI century, spread Spanish over most of the American continent, borrowing that enriched their vocabulary of native languages such as Nahuatl or Quechua, languages on which they also had a notable impact. After achieving independence, the new American states began linguistic unification processes that ended up spreading the Spanish language throughout the entire continent, from California to Tierra del Fuego.

Throughout the 17th and XVIII an infinity of public and private periodicals in Spanish arose. The first was published in Madrid in 1661 by Julián Paredes (Gazeta nueva), and it was followed by numerous publications in Salamanca, León, Granada, Seville and Zaragoza. Periodicals in Spanish are also beginning to appear in bilingual territories. The first was in 1792, the Diario de Barcelona, which was also the first newspaper in Spanish in Catalonia.[citation required] It was followed by El Correo de Gerona (1795), Diario de Gerona (1807) and even earlier in also bilingual cities such as Palma de Mallorca (1778), Vigo or Bilbao. In America, Spanish became the normal language of education, to the detriment of general languages based on indigenous languages. It is estimated that Spanish was known around 1810 by a third of the inhabitants of Spanish America.

The Spanish language has always had numerous variants that, although they respect the main Latin stem, have differences in pronunciation and vocabulary, as happens with any other language. To this must be added contact with the languages of the native populations, such as Aymara, Chibcha, Guaraní, Mapudungun, Maya, Nahuatl, Quechua, Taíno and Tagalog, among others, who also made contributions to the lexicon of the language, not only in their areas of influence, but in some cases in the global lexicon.

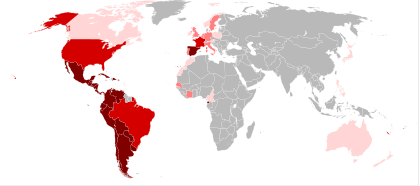

Geographic distribution

Spanish or Castilian is the official language of nineteen countries in the Americas, in addition to Spain and Equatorial Guinea, and it has a certain degree of recognition in the Philippines and in the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (a country not recognized internationally), but its speakers are distributed across the five continents:

America

Around 90% of the total number of Spanish speakers in the world, about 400 million people, are found in the Americas. In addition to 19 countries in Latin America, Spanish is spoken by a significant part of the population of the United States, mainly recent immigrants. Both in Latin America and in the United States there is a significant increase in the number of speakers. Previous presidents of the United States are knowledgeable of the language and Barack Obama studied it and has a good pronunciation in reading.

Hispanic America

The majority of Spanish speakers are found in Latin America, comprising some 375 million people.

Mexico is the country with the largest number of speakers (almost a quarter of the total number of Spanish speakers in the world), although it is not the official language of the state. In 2003, Mexico recognized indigenous languages as national languages as well.

With one name or another, it is one of the official languages of Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, the Dominican Republic and Venezuela. It is not recognized as an official language in other American countries where it is the most widely spoken language, as is the case in Argentina, Chile, Mexico and Uruguay. In Puerto Rico, the 1952 Constitution establishes Spanish along with English as official languages. In September 2015, Senate Bill 1177 was presented to establish the use of Spanish in the first place in the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

United States

The United States is the country with the second most Spanish speakers in the world after Mexico, with a progressive advance in bilingualism, especially in the states of California, New Mexico and Texas, where there are official bilingual programs of Spanish for residents from Latin America. For example, in California many government activities, documents and services are available in Spanish. Section 1632 of the California Civil Code recognizes the Spanish language as the language of the considerable and growing Hispanic community, hence the Dymally-Alatorre law instituted English-Spanish bilingualism, without the necessary exclusion of other languages. In the state In New Mexico, Spanish is even used in state administration, although that state has no official language established in its constitution. New Mexican Spanish spoken by native Spanish speakers of the state (not by recent immigrants) dates back to the times of Spanish colonization in the 16th century and preserves numerous archaisms. The United States Commission on Civil Rights acknowledges that in 1912:

“The Neo-Mexicans succeeded in protecting their heritage, inserting provisions in their constitution that make Spanish an official language like English.”

In Texas, the government, through section 2054.116 of the Government Code, mandates that state agencies provide information on their web pages in Spanish. Other states of the Union also recognize the importance of Spanish in their territory. In Florida, for example, its use is widespread due to the presence of a large community of Cuban origin, mainly in the Miami metropolitan area. Spanish has a long history in the United States; Many states and geographical features have their names in that language, but the use of the Spanish language has increased mainly due to immigration from the rest of America. An example of the expansion of the language in the country is the large presence of the media in Spanish. Spanish is also especially concentrated in cosmopolitan cities such as New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Miami, Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, Denver, Baltimore, Portland and Seattle. Spanish is also the most widely taught language in the country.

The United States is the second country, after Israel, with the highest number of speakers of Judeo-Spanish or Ladino. Specifically, it is estimated that there are about 300,000 people who speak it. The monitoring and accounting of Sephardic communities both in the United States and in the rest of the world has improved notably after the Spanish law of 2015 that allows Sephardim, who meet a series of requirements, to apply for Spanish nationality.

Brazil

Spanish has always been important in Brazil due to the proximity and growing trade with its Spanish-American neighbors, being a member of Mercosur, as well as the historical immigration of Spaniards and Hispanic-Americans. In 2005, the National Congress of Brazil approved the decree, signed by the president, known as the Spanish law, which offers this language as the first foreign language of instruction in schools and high schools in the country. Spanish is an easy language to learn for Brazilians, thanks to the fact that Portuguese is a language similar to Spanish. In the border area between Brazil and Uruguay (mainly in Uruguay) a mixed language called portuñol is spoken. The constitution of the state of Rio de Janeiro and a deliberation of the government of the state of São Paulo include Spanish officially in secondary schools. Thus article 317.3 of the constitution of the state of Rio de Janeiro of 1989 declares:

"The Spanish language becomes part of the obligatory nucleus of disciplines of all the series of the second degree of the state network of education, taking into account primarily what establishes the constitution of the Republic in its fourth, single paragraph".

And article 2 of deliberation no.

"Spanish is a compulsory curriculum component, according to the federal legislation in force, to be developed according to the terms of the guidelines contained in the indication cee n.o 77/08 that is part of the deliberation".

UNILA, a public university in the southern Brazilian region that coordinates and provides Spanish teachers to state schools in Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina and Paraná, made Spanish co-official. In recent years, due to the Venezuelan migration crisis, the Brazilian border state of Roraima has become the place with the most Spanish speakers in Brazil. It is estimated that around 50,000 Venezuelans currently reside in Roraima, constituting approximately 10% of the state's population. In 2005, the then Minister of Education, Fernando Haddad, and the then President of the Brazilian Republic, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, signed Law No. 11,161, which became known as “Lei do espanhol ”. According to its terms, its objective was to deal specifically with the teaching of Spanish in Brazil.

Canada

In Canada, the Spanish-speaking immigrant population accounts for 1.3%, and nearly as many speak it as a second language. Approximately half are concentrated in Toronto. Spanish ranks fourth in foreign languages with 553,495 native language speakers after Mandarin, Cantonese, and Punjabi.

Other countries in Central America and the Caribbean

Spanish is not officially recognized in the former British colony of Belize. However, the majority of the population knows how to speak Spanish, since it is the language of compulsory learning in schools. It is spoken mainly by descendants of Hispanics who have inhabited the region since the 19th century XVII. On the Caribbean island of Aruba, it is spoken by a large number of people, being the second most spoken language in Aruban households according to 2010 census data. On the contrary, in neighboring Curaçao and Bonaire it is spoken by a minority.[ citation required] Due to their proximity to Venezuela, the three islands receive media in Spanish, mainly television channels, due to close commercial ties and the importance of Spanish-speaking tourism. In recent years, the compulsory basic teaching of Spanish in schools has also been introduced, although without official status (the only official languages of Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao are Dutch and Papiamento: a mixture of Spanish and Afro-Portuguese).

Spanish is not an official language of Haiti. Although its official language is French, Haitian Creole (a language derived from French) is widely spoken. Near the border with the neighboring Dominican Republic, basic Spanish is understood and spoken colloquially. In regulated secondary studies, learning Spanish is compulsory from 15 to 18 years of age. It is estimated that more than a million and a half Haitians can communicate in Spanish, without considering the diaspora.[citation required]

In the US Virgin Islands, Spanish is spoken by approximately 17% of the population, mostly from Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. In Trinidad and Tobago, it enjoys a special status and is compulsory learning in public schools. In Jamaica it is the most studied foreign language in secondary education from 12 to 14 years of age. Other Caribbean islands have Spanish-speaking communities due to their proximity to the surrounding Spanish-speaking countries and the corresponding migrations from countries such as the Dominican Republic or Venezuela, which is why Spanish is taught as a second language in the educational system of some of them. them.[citation needed]

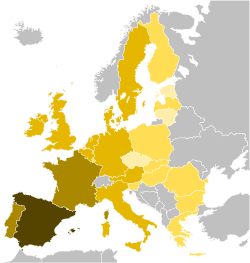

Europe

Spain is the only place in Europe where the language is official, however it is used outside its borders like Gibraltar. In Andorra it is the second most widely spoken language today, without being the traditional or official language, which is the Catalan. Spanish is also used in small communities in other European countries, mainly in Portugal, France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Germany, Belgium and Switzerland (where it is the mother tongue of 1.7% of the population, representing the language most spoken minority in this country behind three of the four official languages). Spanish is one of the official languages of the European Union (EU). Almost 23 million Europeans over the age of 12 speak Spanish outside of Spain in the EU, counting those who have learned it as a foreign language and are able to maintain a conversation. In total there would be about 70 million Spanish speakers in Europe.

In 2020, Russia incorporated Spanish as a foreign language in public education, for a total of 2 hours a week, this occurs after the Russian government made it compulsory to study a second foreign language. Since 2009, Russia launched the RT channel that broadcasts news and reports entirely in Spanish.

Asian

Philippines

Currently, the Spanish language in the Philippines is not spoken by the vast majority of the population. However, its presence in this country —once a Spanish overseas province—, both within the local language and in everyday life, is evident in many commonly used nouns, in the calendar, in religious customs, in the Philippine anthroponyms and in many of their place names (including administrative demarcations).

Spanish was official in the Philippines from 1571 (beginning of Spanish rule of the islands) until 1987, when the "Cory constitution" of that year abolished its official status. Although, starting in 1973, it had lost a lot of representative weight at an official level, with the presidential proclamation/155 of March 15 of that year (still in force today) that declared Spanish as a recognized language only for "all those documents from the colonial era not translated into the national language». Currently, the Philippine constitution only mentions Filipino and English as official languages ("until further notice", according to the text itself), in addition to the indigenous languages in their respective territories. Spanish and Arabic are languages promoted in the constitution on a voluntary basis, and their official status is not mentioned.

After the Spanish-American War, the Philippines became a colony of the North American country from 1899. In the following years, the authorities followed a policy of de-Hispanization in favor of English. After the Philippine-American War, the Spanish-speaking urban bourgeoisie was decimated, which was virtually annihilated after World War II. It has been estimated that in 1907, approximately 70% of the Filipino population had the ability to speak Spanish at some level (although only 10% as their native language); in 1950, it became 6%; and currently figures of between 0.5% and 2% are being considered. Spanish-based creole languages also survive, such as Chabacano from Zamboanga.

Throughout the years, the Philippines has had presidents who are more or less prone to institutional support for the Spanish language and culture in that country. The last Hispanic president was Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, whose educational initiative to introduce Spanish into national curricula earned her the 2009 Don Quixote International Award. In the years following its adoption, it was the second most studied foreign language after English, taught in up to 65 public centers. However, generally it has not been possible to prove that this initiative managed to increase the interest of young people in Spanish, nor are there any indications that there has been any palpable increase in the number of people able to communicate in this language.

Israeli

In Israel there is an important Sephardic community, part of which (figures of tens of thousands of people are considered) still communicates —at different levels— in the Judeo-Spanish language, a legacy of the Jews expelled from the Iberian kingdoms in the XV and XVI centuries span>. In 2018, the National Judeo-Spanish Academy was inaugurated in Jerusalem, officially postulated in 2020 as a member of ASALE, in order to protect, investigate and promote the use of Judeo-Spanish among Sephardic communities and in general. However, a large part of the most recent generations of families of Sephardic origin have abandoned Judeo-Spanish as the vehicular or communication language within the family, while many others have adapted it to modern Spanish (thus keeping the use of Spanish alive). in Israel, but not Judeo-Spanish as a particular language).

Another contribution to Spanish in that country has been the many Jewish immigrants from Latin America, and especially from Argentina and Uruguay, who have brought the typical Río de la Plata accent to different parts of the country.

Other countries

There are other Asian countries where Spanish is being studied with great interest and is beginning to have importance in the educational, migratory and social spheres. Countries where there have been educational initiatives to spread Spanish include Russia, China, Japan, Iran, India, the United Arab Emirates, Bangladesh, and Kuwait. In Turkey, more specifically in the city of Istanbul, Judeo-Spanish is preserved.

Africa

Canary Islands

Forming part of Spain and therefore politically European, the main Spanish-speaking enclave in Africa are the Canary Islands (with more than two million speakers), followed by the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla (with more than 168,000 speakers) and other places of minor sovereignty.

Equatorial Guinea

Spanish is one of the official languages of Equatorial Guinea. Equatorial Guinea gained its independence from Spain in 1968, but maintains Spanish as the official language along with French, and Portuguese, currently being the only African country where Spanish is the official language. It is also the most widely spoken language (considerably more than the other languages). two other official languages), dominated by 87.7% of the population according to the Cervantes Institute. The vast majority of Equatorial Guineans speak Spanish, although always as a second language, with various Bantu languages being the most widespread mother tongues.

Western Sahara and Morocco

In Western Sahara, the Saharawi Minister for Latin America, Hash Ahmed declared on behalf of the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic that his country is "simultaneously an African and an Arab nation that has the privilege of being the only Spanish-speaking nation due to heritage culture of the Spanish colonization. The Spanish language is the compulsory teaching language because it is, together with Arabic, the official language." Spanish is considered the second administrative and communication language of the SADR; the only official language in its constitution is Arabic. In Tindouf, Algeria, there are some 200,000 Saharawi refugees, who can read and write the Spanish language, and thousands of them received university education offered by Cuba, Mexico, Venezuela and Spain.

In Morocco, the Spanish language is very popular as a second or third language. It is spoken mainly in the areas of the former Spanish protectorate of Morocco: Rif, Ifni and Tarfaya. Haketía, a Moroccan variant of Judeo-Spanish, is also preserved in the north of the country.

Other countries

In addition, it is spoken by the Equatoguinean communities who fled during the dictatorships of Francisco Macías Nguema and Teodoro Obiang and are now found in countries such as Gabon, Cameroon, Nigeria and Benin. Also in South Sudan there is a significant minority, the intellectual and professional elite, trained in Cuba, who speak Spanish. Other places where Spanish is present are Angola, mainly in the city of Luena, and Walvis Bay, a city in Namibia, due to the presence of the Cuban army.

At the request of Equatorial Guinea, Spanish is the working language of the African Union and through an amendment to article 11 of the Constitutive Act of the African Union, Spanish has been included among the official languages "of the Union and all its institutions".

Rest of the world

Oceania

Among the countries and territories of Oceania, Spanish is the de facto official language on Easter Island, in Polynesia, as it is part of Chile; the native language is Rapanui. In the Mariana Islands (Guam and the Northern Marianas) Chamorro is the official and native language of the islands, which is an Austronesian language that contains a lexicon of Spanish origin. Some islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (Saipan), Tinian, Rota) and the Federated States of Micronesia (Yap, Pohnpei) had native Spanish speakers, since they were Spanish colonies until 1898-1899. However, both in Guam and in the Northern Marianas, a good part of its inhabitants have surnames of Spanish origin.

In addition, in Australia and New Zealand, there are communities of native Spanish speakers, resulting from emigration from Spanish-speaking countries (mainly from the Southern Cone), totaling 133,000 speakers. In Hawaii, 2.1% of the population they are native Spanish speakers. In 2010 there were 120,842 Hispanics, according to the United States Census.[citation required]

Antarctica

In Antarctica, there are only two civilian localities and both are inhabited mainly by native Spanish speakers. One of them is the Argentine Fortín Sargento Cabral, which has 66 inhabitants. The other is the Chilean town of Villa Las Estrellas, which has a population of 150 inhabitants in summer and 80 inhabitants in winter. In each of them there is a school where they study and do research in Spanish. The Orcadas Antarctic base, an Argentine scientific station, is the oldest base in all of Antarctica still in operation and the oldest with a permanent population (since 1907).

It is also worth noting the role played by the different scientific bases of Antarctica belonging to Hispanic countries:

| Country | Permanent bases | Summer bases | Total | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 6 | 7 | 13 |  |

| Chile | 4 | 5 | 9 | |

| Uruguay | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Spain | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Peru | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ecuador | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Estimate of total speakers by country

- In the rows with darker background, there are the countries with official Spanish. The estimate of the total number of speakers refers to Spanish speakers as first and second language.

- In the rows with white background, there are countries with non-official Spanish, where Spanish is spoken as a mother tongue by the Hispanics who have emigrated there and by Spanish speakers as a foreign language.

Expanding language

By the year 2000, the forecast was that the number of Spanish-speakers in the United States alone would reach 35,000,000. In that year, Spanish surpassed English as the most spoken language in the Western world. In 2001, Spanish-speakers were approximately 400 million people.

The Instituto Cervantes, an organization for the dissemination of Spanish, reported that between 1986 and 1990 there was an increase of 70% in the number of Spanish students in the United States and 80% in Japan. The Spanish language is perhaps the third most studied foreign language in Japan. Currently, Portuguese is the most studied first foreign language, due to the large Japanese/Brazilian community, with a total of 400,000 speakers. As such, the Portuguese language is currently part of the school curriculum in Japan. Other countries that stand out for their high increase in students are Brazil, Morocco, Sweden, Norway, Poland, Ivory Coast, Senegal, Cameroon and Gabon.

However, in recent decades there have also been setbacks. The most notable case is that of the Philippines, a country in which the Spanish language went from being official to having a restricted role since 1973, and finally losing its official status in 1986; thus, after a process of substitution in favor of English and Tagalog, in a few decades it went from tens of millions of speakers in the Philippine archipelago [citation needed] to no over 20,000 in 1990. The total number of speakers is increasing very slightly in recent years due to initiatives by the Philippine government to reintroduce the language into teaching, but they are no longer native speakers.

Official academic sources estimate that by 2030 Spanish will be the second most spoken language in the world, behind Mandarin Chinese, and by 2045 it is expected to become the first.

Spanish students around the world

Students of Spanish as a foreign language, according to the Instituto Cervantes 2015 yearbook. Only countries where there are more than 30,000 are shown.

Informal education

The data for people who study Spanish only includes centers that are certified by the Instituto Cervantes; however, due to new technologies, the way of studying has changed in all areas; applications on smartphones is a clear example of this.

On the Duolingo web platform, Spanish is the second most studied language in the world, with more than 36 million students. According to its 2020 report, Duolingo reported that Spanish had grown in popularity, displacing French as the second most studied language in the world, growing to be the most popular language in 34 countries and the second most popular in 70 countries. As of 2016, Spanish was the most studied language in 32 countries and the second most studied in 57 countries.

| Language | English | Spanish | French |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a option (n. of countries) | 121 | 34 | 23 |

| 2a option (n. of countries) | 8 | 70 | 71 |

| Users (millions) | 104.82 | 36.08 | 27.87 |

Note: Total users per language, data updated to March 2021.

In 2020, out of a total of 19 languages available on Duolingo, English was studied by 53% of users, especially in regions such as Latin America, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. Spanish, with 17% of users, stands out in countries like the United States, the United Kingdom and Norway, and at a regional level, in Anglo-Saxon America. Since the English version, Spanish has 27 million users; that is equivalent to 80% of the total who study Spanish. It is followed by the Portuguese version with about 3 million users.

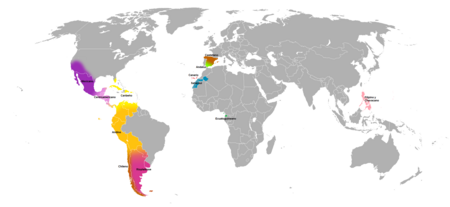

Varieties of Spanish dialects

The geographical varieties of Spanish, called dialects or geolects, differ from one another for a multitude of reasons. Among those of a phonetic type, the distinction or not of the phonemes corresponding to the spellings c/z and s (absence or presence of lisping/lisping), the distinction or not of the phonemes corresponding to the spellings ll and y (absence or presence of yeísmo), the aspiration or not of the s or z before a consonant, and the adoption or not of new consonants (such as /ʃ/). These differences do not usually cause intelligibility problems between their speakers. The various variants also differ in grammatical uses, such as voseo or the use or not of the informal second-person plural pronoun ("you"). In aspects of vocabulary, there are notable differences, especially in certain semantic areas, such as the nomenclature of fruits and vegetables, clothing, everyday items, as well as in colloquial or insulting expressions.

As in any language, especially when it is distributed over a large geographical domain, Spanish presents various internal varieties that allow its speakers to be distinguished according to their pronunciation, their grammatical constructions and their vocabulary. In general terms, Spanish conventionally presents two types of modalities present both in Spain and in America: conservative modalities, such as the Spanish of northern Spain, the interior of Colombia and Mexico or the Andes, and innovative modalities, like the Spanish of Andalusia and the Canary Islands, the Caribbean or the Río de la Plata. A typical characteristic of peninsular Spanish is the division of the consonant cluster tl which, in words such as atlas or atletismo is pronounced [' at.las] and [at.le.'tis.mo], while in Latin the current pronunciation is ['a.tlas] and [a.tle.'tis.mo].

Independently of these features, it is possible to distinguish large groups of dialectal varieties of Spanish. For example, for Menéndez and Otero (2007) there would be eight: the Castilian, Andalusian and Canary varieties in Spain, and the Caribbean, Mexican-Central American, Andean, Chilean and River Plate varieties. In America.

Differences between dialects are almost always limited to intonation, pronunciation, and single words or expressions. One of the differences between the dialects of Spain and those of Latin America are the pronouns. In Spain, the only second-person informal pronoun used is "tú", but in some areas of Latin America such as Argentina, Uruguay or Paraguay, "vos" is used. «Tú» and «vos» are informal and are used with friends. "You" is a formula of respect that is used with strangers or older people. However, in certain regions of Colombia the ustedeo can occur in areas of a certain informality comparable to the use of the tuteo or the voseo in the aforementioned countries.

«Vos» is used as the second person singular in many places in Latin America (see #Voseo).

Dialects of Spanish also vary when it comes to the second person plural. The dialects of America only have one form for the second person plural: ustedes, which is used for formal and informal situations. However, in European Spanish there are two: you for formal situations and you for informal situations.

| Dialectos en España | ||

| ||

| Dialects in Africa | ||

| ||

| Reparaciones en América | ||

|

| |

| Dialects in Asia | ||

| ||

Derived languages

The following are languages that can be considered Spanish-derived and Spanish-influenced Creoles:

- Judeo-español, Sephardic or Ladino, language spoken by the Sephardic Jews, and their Moroccan dialect, called Haquetía;

- Creole languages:

- Babacano, spoken Creole language in the Philippines and in parts of Insulindia—Zamboanga, Cavite, Semporna, Ternate and Tidore;

- Papiamento, Creole language mix of Spanish, Portuguese and other languages, spoken in the south of the Caribbean, with different variants: Papiamento de Aruba, Papiamento de Bonaire and Papiamento de Curacao;

- Palenque de San Basilio (Colombia).

| Castellanomedieval |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Languages relexicalized by Spanish

In the world there are several mixed languages and pidgins that take a large part of their lexicon from Spanish:

- with English:

- spaanglish, spoken in the United States;

- Plain, spoken in the British territory of Gibraltar;

- with the Portuguese:

- portuñol, mixed language spoken in the border areas between Brazil and the neighbouring Spanish-American countries.

- with the Guaraní:

- yopará, speaks with a strong influence and lexicon from Spanish, spoken in Paraguay and the northeast of Argentina;

- with the northern chichua:

- half language, mixed language that has 89% Spanish lexicon and quichua grammar, is spoken in Ecuador.

Linguistic description

Classification

Spanish is an Indo-European language of the Romance subfamily, specifically a language of the Ibero-Romance group, so the closest languages to it are Asturian-Leonese, Galician-Portuguese and Aragonese. Typologically, it is an inflectional fusion language, with an initial nucleus and complement marking, and the basic order is SVO (declarative sentences without topicalization).

Phonology and sounds

Modern Spanish has a markedly different phonology from Latin. In modern standard Spanish the opposition of quantity in vowels and consonants has been lost and the stress is not prosodically determined but rather phonologically distinctive. In modern Spanish, voiceless sounds (without vibration of the vocal cords) are always obstruents (fricatives, affricates, or stops), while voiced sounds are frequently continuous (approximates, sonorants, or vowels). The only obstructive sounds that are voiced without being due to assimilation are the stops /b, d, g/ (in absolute initial position or after nasal). Medieval Spanish had voiced affricates and fricatives (still present in other Romance languages and even in Judeo-Spanish but systematically voiceless in modern standard Spanish).

In the transition from Latin to Spanish, some distinctive changes can be seen, such as the presence of lenition (Latin vita —Spanish 'life'—, Latin lupus —Spanish 'wolf'—), the diphthongization in the phonetically short cases of E and O (Latin terra —Spanish 'earth'—, Latin novum —Spanish 'new' —), and palatalization (Latin annum —Spanish 'year'—). Some of these features are also present in other Romance languages.

The most frequent phoneme in Spanish is /e/, so also the letter «e» is the most repeated letter in a long text in Spanish. The most frequent consonant phoneme in all the varieties is /s/, although as a consonant letter the « r" is a little more frequent than "s" (this is because the phoneme /r/ when it does not go to the beginning or end of a word is written double, with which the The frequency of that letter exceeds that of the phoneme. The frequency of «r» is even more increased because when it is found inside a word it represents the phoneme /ɾ/, simple trill).

The accent is of intensity and statistically flat words dominate, or words accented on the penultimate syllable, then the acute ones and finally the esdrújulas. Thanks to the Royal Spanish Academy, founded in 1713, the spelling of Spanish has been simplified by looking for the phonetic pattern, although this trend stopped in the middle of the century XIX, despite the proposals in this sense of the grammarian Andrés Bello.

Vowels

In all variants of Spanish there are five phonological vowels: /a and i or u/. The /e/ and /o/ are mid vowels, neither closed nor open, but they can tend to close and open [e], [ɛ], [o] and [ɔ] depending on their position and the consonants for which they are attached. they are stuck However, these sounds do not represent a distinctive feature in most varieties, unlike what happens in Catalan, Galician, Portuguese, French, Occitan and Italian; in Spanish these sounds are therefore allophones. However, in the varieties from the southeast of the Iberian Peninsula (eastern Andalusian and Murcian) the opening feature is phonological, and therefore these geolects have up to 10 vowels in opposition (singular [el 'pero] / plural [lɔ perɔ]).

According to Navarro Tomás, the vowel phonemes /a/, /e/ and /o/ have different allophones.

The vowels /e/ and /o/ have somewhat open allophones, very close to [ɛ] and [ɔ], in the following positions:

- In contact with the sound of double erre (“rr”) /r/, as in “dog”, “torre”, “remo”, “roca”.

- When they go before the sound /x/, as in “teja”, “hoja”.

- When they are part of a decreasing diptongo, as in “peine”, “boina”.

- In addition, the open alophone of /o/ occurs in all syllable that is locked by consonant and the open alophone of /e/ appears when it has been locked by any consonant that is not /d/, /m/ and /n/: “pelma”, “fish”, “pez”, “costa”, “olmo”.

The phoneme /a/ presents three allophonic varieties:

- A palatal variety, when it precedes palatal consonants, as in “bad”, “small”, “unpaid”.

- Another careful variant occurs when it precedes the vocals /o/, /u/ or the consonants /l/, /x/: “now”, “pausa”, “palma”, “maja”.

- An average variant, which is made in the outlines not expressed in the preceding paragraphs: “caro”, “compás”, “sult”.

Both /i/ and /u/ can also function as semivowels ([i^] and [u^]) in postnuclear syllable position and as semiconsonants ([j̞] and [w̞]) in prenuclear position. In Spanish there is a pronounced antihiatic tendency that frequently turns hiatuses into diphthongs in a relaxed pronunciation, such as héroe ['e.ɾo.e]-['e.ɾwe], or línea [&# 39;li.ne.a]-['li.nja].

In addition, in Spanish all vowels can be nasalized when they are locked by a nasal consonant, resulting in [ã], [ẽ], [ĩ], [õ] and [ũ]. This feature is more prominent in some linguistic varieties than in others.[citation needed]

In various dialects of Spanish from the southeast of Spain, such as eastern Andalusian and Murcian, among others, between 8 and 10 vowels are distinguished, and even 15 if nasal vowels are counted, which are very present in these dialects; this phenomenon is sometimes accompanied by vowel harmony. When any vowel is locked by an “s” (mute), or by the other consonants (mute), they result in the following vowels /ɑ/, /ɛ/, /ɪ/, /ɔ/ and /ʊ/; thus forming the following vowel pairs: /a/-/ɑ/, /e/-/ɛ/, /i/-/ɪ/, /o/-/ɔ/ and /u/-/ʊ/. These vowel pairs are distinctive in these dialects, such as hasta and asta /ɑt̪a/ - ata (verb to tie) /at̪a/, mes /mɛ/ - me /me/, los /lɔ/ - lo /lo/.[ citation required]

Unlike the above, Mexican Spanish pronounces unstressed vowels in a weak or deaf manner, mainly in contact with the sound /s/. Given the case that the words pesos, pesas and peces have the same pronunciation ['pesə̥s].[citation required]

Consonants

All varieties of Spanish distinguish a minimum of 22 phonemes, five of which correspond to vowels (/a e i o u/) and 17 to consonants (/b s k d f g x l m n ɲ p r ɾ t ʧ ʝ/). Some varieties may have a greater number of phonemes; for example, in the Iberian Peninsula most dialects have the additional presence of /θ/ and in some speakers from various areas of Spain and America the phoneme /ʎ/ also persists (which was present in medieval Spanish). However, the number of sounds or allophones (which are not necessarily phonologically distinctive) is notoriously higher in all varieties of Spanish; to see a list of some, see Spanish phonetic transcription. Dialectal phonological differences, mostly due to differences in consonants, are as follows:

- No Spanish dialect makes the spontaneous distinction between the pronunciation of the letters “b” and “v”. This lack of distinction is known as bitacism. However, it must be borne in mind that in some countries, particularly Chile, children are very pressured at school to proclaim 'v' as a lipdental, so one may occasionally encounter this pronouncement (perceived by many as affected), especially in the media. The pronouncement of “v” as an occlusive or fricative bilabial fonema, identical to that of “b”, is also shared with the Galician, Sardinian and various dialects of Catalan and West, among others. A possible cause of this peculiarity is the influence of the Basque linguistic substrate, which would explain its extension in these languages quoted from a Basque-Pyrenean focus. Another possible explanation, rather structural, is that although Latin had the letter 'v' which was actually only a written variant of the 'u' semivocal, it was pronounced /w/ and evolved into other languages romances towards /v/. On the other hand, the fricativization of /b/, common in all the Romance languages, led to the alófonos /b/ oclusivo y /β/ fricativo. The second has a certain resemblance to the approximate /w/, so the 'v' [w] latina would have gone directly to [b, β] in Spanish. However, there is the /v/ sound in Spanish when a “f” is in contact with a sound consonant, in the same way a /s/ and /θ/ sounding occurs when contacting a sound consonant turning /z/ and /ð/, respectively. Example: Dafne ['davne], [roz'β.iv ð.e te eclipse'ne margina].

- In general, there is confusion between the consonant “y”, pronounced [.], [.], [κ] or [/25070/], and the “ll”, originally [.], except in various areas of Spain (in regression) and, in America, in Paraguayan Spanish and in the dialects with substrates of languages in which there is such a difference, as in the Spanish-Quechua or Spanish-ai-Spanish bilingual zones. This lack of distinction is known as Yeism.

- In most varieties of America and southern Spain /s/ is a laminoalveolar sound, while in other American varieties (most Peru, Bolivia, scattered areas of Colombia, Mexico, Venezuela and Dominican Republic) and in the center and north of Spain the /s/ is apicodental [s.].[chuckles]required]

- The representation of the consonant / mediante/ by the letter “ñ” (proper of the Latin groups) is considered a particular and singular characteristic of the Spanish language. nn and andV that in the Middle Ages began to abbreviate as a “n” with a tilde (~) above that it then took the undulating form representing its palatal pronunciation), although it also exists in many more languages of the world: asturleonés, the Aragones, the Breton and the Galician, the Guaraní, the Mapudungun, the Mixteco, the Otomi and the Quechua in Africa. In the Spanish language of Yucatan the letter “ñ” is pronounced instead of [,], and therefore sometimes it is translated as “ni”.

- The Spanish of Spain, except the Canary Islands and much of Andalusia, distinguishes between [θ] (written 'z' or 'ce', 'ci') and [s]: house ['kasa], hunt ['kaθa].

- Most of the dialects record a more or less advanced loss of the /-s/ implosive (postvocálica or silabical elbow), a typical phenomenon of American 'lowlands', in a process similar to that of medieval French. The exceptions are Mexico (except some coastal areas of the Caribbean), half north of Spain (where it begins to appear) and in the Andean area (especially in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia).[chuckles]required]

- By influence of the Nahuatl the Spanish of Mexico pronounces the “tz” and “tl” digits as African sounds: an African sound alveolar deaf /t booklets/ and another African side alveolar deaf /t book//, respectively. The first of them only appears in native terms, the second now applies to words that are not loans as Atlantic or Nestlé. Note that Atlantic and Nestlé they pronounce [a.'t redunda͡an.ti.ko] and [nes.'t offset͡e] in Mexico, while in Spain they pronounce [ad.'lan.ti.ko] and [nes.'le], respectively. On the other hand, given that the letter “x” represents the sounds [ks], [gs], [s], [x] and [ь] in the Spanish of Mexico, there may be several pronunciations for the same word. For example, xenophobia is pronounced as [seno'foβia], [γeno'foβia] or even [xeno'foβia]. This last statement has been recorded in the speeches of several Mexican diplomats and writers, such as Adolfo López Mateos, Alfonso Reyes Ochoa and others. Likewise, xilocaine is pronounced [xiloka'ina], and xylophone becomes pronounced as [si'lofono] or [ARIAi'lofono].

Phonology of Spanish

The Spanish phonological system is made up of a minimum of 17 consonantal phonemes (and some varieties in Spain can present up to 19 phonemes by having the phonemes /ʎ/ and /θ/ in addition). As for the vowels, most varieties only have 5 phonemes and several allophones. In some varieties of Andalusian and other southern Spanish dialects they can have up to 10 vowels in phonological opposition, since in them the opening ATR feature can become relevant, doubling the number of vowels.

All these phonemes are analyzable through a minimum of 9 binary features (for varieties without /θ/): [± consonant], [± sonant]; [± dorsal], [± labial], [± coronal], [± palatal], [± velar]; [± continuous], [± nasal], [± lateral]. Although normally, in order to make the description more natural, some more are used, including some more explicit articulatory descriptions:

- For example, crowns are often referred to as alveolars or tooths.

- non-sorting consonants are usually divided into occlusives if they have the [- continuous] and fricative trait if they have the [+ continuous] trait.

The table of consonants in terms of these features is given by:

| RASGS [+consonant] | [-dorsal] | [+dorsal] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [+lab][-cor] | [-lab][+cor] | [+pal][-vel] | [-pal][+vel] | |||

| [-son] | p | d | t implied | k g | ||

| [+cont] | f | (θ) s | x | |||

| [+son] | [+nas] | m | n | |||

| [-nas] | [+lat] | l | ()) | |||

| [-lat] | r | |||||

Where the phonemes that are not present in all varieties of Spanish have been indicated by parentheses (•).

Pronunciation speed

A study carried out by the University of Lyon compared the following languages: English, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Mandarin, Spanish and Vietnamese. It was concluded that only Japanese is capable of surpassing Spanish both in speed and low information density per pronounced syllable. The figures for the Spanish language were: 7.82 syllables per second, compared to the average of 6.1 syllables in English in that same fraction of time, confirming that the speed of the language is due to adaptation to its structure.

Alphabet

The alphabet used by the Spanish language is the Latin alphabet, of which 27 letters are used: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, ñ, o, p, q, r, s, t, u, v, w, x, y, z.

In modern Spanish the «h» does not correspond to any phoneme (although in old Castilian and some modern regional dialects it still represents the phoneme /h/). All variants of Spanish have at least 22 phonemes (17 consonantal and five vowels), some variants having up to 24 phonemes (two phonemes that appear in central and northern Iberian Spanish and do not appear in all variants are /θ/ and /ʎ /). Furthermore, there is no exact correspondence between the other letters and phonemes (for example, «c» = /k/ before /a, o, u/ and /θ/ before /e, i/ in Spain). Likewise, five digraphs are also used to represent as many phonemes: «ch», «ll», «rr», «gu» and «qu», the latter two being considered as positional variants for the phonemes /g/ and /k/.

The digraphs ch and ll were considered as independent letters of the Spanish alphabet from 1754 to 2010, so both graphic signs were listed separately in dictionaries from 1803 to 1994, because they maintain their own pronunciation that is different from that of the individual letters that compose them (c and l). Likewise, the majority of Spanish speakers speak varieties that present yeísmo, under which the pronunciation of the ll is identical to that of the y when the latter is pronounced as a consonant, although its sound is traditionally considered a palatal lateral phoneme.

The letter «r» can represent the phoneme /ɾ/ (final or beginning of a middle syllable) or /r/ (beginning of a word, or after consonants) as the following examples show:

- give /'da' angularokas/

- da rocks /'da'rokas/

- give rocks /'da margin'rokas/

- Israel (no /isra'el/)

- smile /sonre'i echo/ (no /son margin/)

On the other hand, the digraph «rr» always represents the phoneme /r/.

Grammar

Spanish is an inflectional language of the fusional type, that is, in sentences inflection is preferably used to indicate the relationships between its elements. However, despite its nature as an inflectional language, it also resorts to the use of prepositions, abstract words that serve as a link and are invariable. Because of the way in which the arguments of transitive and intransitive verbs are marked, it is grouped within the nominative-accusative languages.

In the noun and the adjective, the categories of number and gender are obligatory, which is manifested both in the endings and the form of the article that requires a noun or adjective when preceded by an article. Personal pronouns distinguish the categories of number and case and in the third person also gender. The verb systematically distinguishes between singular and plural forms, it also has forms according to time, mode, aspect and voice.

Morphology

Spanish words are formed by means of lexemes or roots to which grammatical morphemes or gramemes are added (such as the masculine or feminine gender and the singular or plural number for nouns and adjectives, and the mode, tense, voice, aspect and person and number for the verb), plus all kinds of affixes that serve to form derived words or to mark affectivity, as occurs with the especially abundant and characteristic derivation in diminutive suffixes, many of them rather local use. Suffixation is used for both inflection and derivation, while prefixation is always derivative, never inflectional. Inflection can also be performed suprasegmentally through the position of the accent:

- (I) encourage (1.ap. sg pres ind)

- (he) encouraged (3.ap. sg pret perf simp ind).

Syntax

Syntax is the field of sentences and their syntactic constituents, and deals with studying the way in which the discrete elements of language are combined with each other, as well as the restrictions of syntactic order, co-occurrence and concordance, existing between them.. The most common basic order with verbs (other than inergatives) and with a definite subject and object is SVO, although pragmatically the order of these elements is quite free. The order constraints almost exclusively affect clitics and elements of negative polarity, and elements related to functional categories.

Compound sentences in Spanish include complex consecutio temporum constraints and constraints due to the distinction between an indicative mood and a subjunctive mood. Frequently the rules for choosing the mode of the subordinate clause are not simple. In fact, this is one of the most difficult aspects for students of Spanish as a second language.

In addition, Spanish, like most Indo-European languages and unlike languages such as Chinese or Japanese, extensively uses various types of number, gender, and polarity agreement. These concordance relationships often occur between different phrases. Typologically, Spanish is an initial core language and few order restrictions regarding verbal arguments and syntactic adjuncts. In addition, Spanish is a language that preferentially uses complement marking.

Voseo

In some variants of American Spanish, the form vos is used for the second person singular pronoun instead of the standard tú; normally this variation is accompanied by a particular conjugation.

In the Spanish of the peninsula, vos was, at first, a treatment proper only to nobles or as a form of respect similar to the current usted (vuestra thank you). The irruption of the form vuestra merced, progressively contracted to usted, restructured the use of pronouns in Spain, so that vos began to be used as a formula for equal treatment and competed with you. With the passage of time, the cultured use of Spain rejected vos, leaving usted as a form of respect and tú for family use or among equals. The colonization of America in the late 16th century occurred when vos was still used for dealing among equals and with this value it was implemented in various areas as a popular form of treatment for the second person singular, but it lost its prestige connotations. In Spain it does not survive today, although the second person plural form vosotros does, which also has its origin in the Latin vos. The educated urban centers of America that were more exposed to the influence of European Spanish followed the restructuring of the pronouns of the peninsula and rejected the vos in favor of the familiar familiarity (almost all of Mexico, the Antilles and Peru)., while in the rest the voseo has survived, with different considerations, until today.

Voseo occurs strongly in Argentina, Bolivia (east), Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, and Uruguay. It appears, in slightly different ways, in Venezuela (northwest), Colombia (west), and Chile. Less frequently and limited to a family environment, "vos" can be found in Mexico (central and highlands of Chiapas), Colombia (Pacific coast), Ecuador (highlands), Chile (north and south) and in smaller areas of the interior from Mexico (Tabasco), Panama (Azuero Peninsula), Ecuador (south), Belize (south) and Peru (north and south). In Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic its use is extinct.

Only in the area of the River Plate, Antioquia, Camba and Central America is it regularly used as a prestigious form; in other regions there is some diglossia between both conjugations.

In Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay the «vos» has even almost completely displaced the «tú» from the written sources. However, there are writers from the River Plate who still maintain the classic form "tú" for their works of fiction, such as the Uruguayan poet Mario Benedetti.

In Guatemala the familiar term is used more frequently between people of different sexes, when a man speaks to a woman he doesn't know, generally the address is "you", when there is more confidence he voses.

In El Salvador the familiar familiarity is common, it is used as a courtesy or respect in certain registers, for example, when speaking with foreigners, when speaking in public, advertising, correspondence, etc. If the situation is spontaneous, both are usually used. It is normal among equals, and mostly among the lower class, not the voseo which is normal among the middle and upper class.

In Nicaragua the use of «tú» is extinct, the entire population uses «vos» for informal situations and «usted» for formal ones. If someone speaks a familiar name, is considered a foreign person, or someone who imitates another culture, the use of "tú" or its conjugation in some phrases or sentences is the result of many Spanish-American soap operas where the familiar name is common.

In Costa Rica, vos is very common as an informal pronoun, while «usted» is the formal pronoun. There are speakers who exclusively use "you", regardless of whether their use is formal or informal. There are also speakers who use the familiar term, but this use is rejected by the voseantes speakers.

In Venezuela, the voseo is common in Zulia State and in the central-western part of Falcón State.

Lexicon

The Spanish lexicon is made up of around 70% words derived from Latin, 10% derived from Greek, 8% from Arabic, 3% from Gothic, and 9% from words derived from different languages.

There are quite a few place names of the pre-Roman languages of the peninsula (Iberian, Basque, Celtic or Tartessian), some words (barro, perro, cama, gordo, nava) and some isolated anthroponyms, such as Indalecio. The settlement of Germanic peoples such as the Visigoths, the Vandals or the Suevi inserted quite a few first names (Enrique, Gonzalo, Rodrigo) and their respective surnames (Enríquez, González, Rodríguez), the suffix -engo in words like "royal" and vocabulary related to war like "helm" and "spy".

In addition, the aforementioned Muslim era gave way to the adoption of numerous Arabisms. In morphology, it should be noted that the suffix -í of gentilisms such as "ceutí" or "israelí" comes from Arabic.

In the XVI century, numerous Italianisms referring to the arts were introduced, but also a large number of indigenous words or Americanisms, referring to plants, customs or natural phenomena typical of those lands, such as sweet potato, potato, yucca, cacique, hamaca, hurricane, cocoa, chocolate; from Nahuatl, the Mayan languages, the Arawak languages (primarily Taino) and Quechua. In the XVII century numerous cultisms entered through the influence of the Gongorina or culterana language. In the 18th century, Gallicisms or words borrowed from French referring above all to fashion, cooking and bureaucracy as puree, tissue, menu, toupee, mannequin, restaurant/restaurant, bureau, card, gala and DIY, among others. In the XIX century, new borrowings were incorporated, above all from English and German, but also from Italian in fields related to music, especially opera (baton, soprano, piano, radio), and cooking. In the 20th century the pressure of English in the fields of technology, computing, science and sports increased greatly: set, penalti, soccer, e-mail, Internet, software. All of these are known as loanwords.

However, the Royal Spanish Academy has made great efforts in recent years to avoid the use of these words, proposing alternatives more in line with the traditional spelling of Spanish (among many other examples: zum instead of zoom, email instead of e-mail, soccer instead of football…). Although most of these initiatives have been permeating society, certain proposals have not been very well received, despite being recommended by the RAE.

In general, America is more susceptible to borrowing from English or anglicisms (“mouse”, in Spain: “ratón”), largely due to its closer contact with the United States. For its part, Spain is the same for Gallicisms or words taken from neighboring France (such as the Gallicism "ordenador" in the Spanish of the Iberian Peninsula, in contrast to the Anglicism "computadora" or "computadora" in American Spanish).

Regarding the Slavic languages, most loanwords come from the Russian language. However, there are also words in Spanish that come from Czech and Slovak. Most of the Czech loanwords were assimilated into Spanish from other languages, such as French and English, with Czech origin, such as pistola or robot. However, most of the words from Czech are eponymous nouns.

Writing system

Spanish is written using a variant of the Latin alphabet with the additional letter «ñ» (eñe) and the digraphs «gu», «qu», «rr», «ch» and «ll», considered the last two as letters of the alphabet from 1754 to 2010, and which were listed apart from «c» and «l» between 1803 (fourth edition of the DRAE) and 1994, because they represent a single sound, different from the letters that compose it.

Thus, the Spanish alphabet is made up of twenty-seven letters: «a», «b», «c», «d», «e», «f», «g», «h», «i», «j», «k», «l», «m», «n», «ñ», «o», «p», «q», «r», «s», «t», «u », «v», «w», «x», «y» and «z».

The digraphs «ch» and «ll» have specific phonetic values, so in the Ortografía de la lengua española of 1754 they began to be considered as letters of the Spanish alphabet and from the publication of the fourth edition of the Dictionary of the Spanish language in 1803 they were ordered separately from «c» and «l», and it was during the X Congress of the Association of Academies of the Spanish Language held in Madrid in 1994, and on the recommendation of various organizations, that it was agreed to rearrange the digraphs "ch" and "ll" in the place assigned to them by the universal Latin alphabet, although they were still part of the alphabet. With the publication of the Ortografía de la lengua española of 2010, both ceased to be considered letters of the alphabet.

In addition, unlike other languages in the rest of the world, Spanish is the only language that uses graphic question marks and opening exclamation marks that other languages do not have ("¿" and "¡"), which they are placed at the beginning of the question or exclamation, and at the end of the question or exclamation their respective closing counterparts ("?" and "!"). In this way, Spanish can be differentiated from other languages in reference to the creation of questions and exclamations (note that these opening signs were introduced in the second edition of the Ortografía de la Real Academia de la Lengua). These special signs make it easier to read long questions and exclamations that are only expressed orally by intonation variations. In other languages «¿» and «¡» are not necessary because their oral syntax does not cause ambiguity when being read, since there are subject inversion, special auxiliaries, locutions ―for example: Is he coming tomorrow?, Vient-il demain?, Kommt er morgen?, Are you coming tomorrow?―.

The vowels always constitute the center or nucleus of the syllable, although the «i» and the «u» can function as semiconsonants before another vowel nucleus and as semivowels afterwards. A vowel nucleus of a syllable can sound stronger and higher than the rest of the syllabic nuclei of the word if it carries the so-called intensity accent, which is written according to orthographic rules with the sign called orthographic accent or tilde to mark the voice hit when it is present. does not follow the usual pattern, or to distinguish words that are spelled the same (see diacritical accent).

In addition, the letter «u» can have an umlaut («ü») to indicate that it is pronounced in the groups «güe» and «güi». In poetry, the vowels «i» and «u» can also have umlauts to break a diphthong and suitably adjust the metric of a certain verse (for example, «ruido» has two syllables, but «ruïdo» has three). Spanish is a language that has a marked antihiatic tendency, which is why hiatuses are usually reduced to diphthongs in relaxed speech, and even reduced to a single vowel: Indo-European > *Indo-European > *Induropean; now > *hurry > *ara; hero > *herue.

Other representations

Economic value of language in Spain

A study by a private foundation suggests that the economic value of the Spanish language in Spain is estimated at 15.6% of the country's GDP. Currently, three and a half million people have jobs directly related to Spanish, one million more than the past decade. In addition, sharing the Spanish language explains that commercial exchanges between Spain and Latin America, in particular, are multiplied by 2.5 times. Sharing Spanish increases bilateral trade between Spanish-speaking countries by 290%.

They are also factors of economic value; language teaching itself, the cultural industry, publication publishing, gastronomy, science, architecture, sports and tourism.

According to the Cervantes Institute, the number of language tourists arriving in Spain has grown by 137.6% from 2000 to 2007. And the Spanish tourism sector figures the income from language tourism in Spain in 2007 at 462.5 million euros. The 237,600 students who arrived in Spain that year spent 176.5 million on Spanish courses, of which 86 % went to private language centers and the remaining percentage to universities.

The Royal Spanish Academy and associated academies

The Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) and the rest of the Spanish Language Academies jointly form the Association of Spanish Language Academies (ASALE), which declares that its purpose is to promote the unity, integrity and development of the Spanish language. As regulatory entities, they work to disseminate the rules for the prescriptive use of language and recommend their application in the spoken and written language. These norms have been reflected in various works on grammar, spelling and lexicography, in particular the Ortografía de la lengua española (1999), the Diccionario panhispánico de dudas (2005), the New Grammar of the Spanish Language (2009) and the Dictionary of the Spanish Language, with 23 editions published between 1780 and 2014 (the last one being revised in 20179 and updated in 201810 with the designation electronic version 23.2).

ASALE currently covers 24 academies, all in countries where Spanish is the official or de facto vehicular language, plus the United States and Israel. The case of Israel is atypical as it is not a majority Spanish-speaking country, but rather where the institutions that preserve, investigate and promote the use of Judeo-Spanish are located, so they are not subject to the application of the current regulations of the Spanish language.. To this end, the National Judeo-Spanish Academy was established in 2018, being the last to join ASALE (in 2020).

As of today, there are no Spanish Language Academies in other territories that have an intense historical, and especially linguistic, link with Spain (such as Andorra, Western Sahara or Belize), so the Royal Spanish Academy maintains the tradition of appointing corresponding academics to recognized personalities in the field of the Spanish language in said territories.

* Date of recognition and integration into ASALE

Other associations related to the Spanish language in the world

Contenido relacionado

Romansh

Nihon-shiki

Terminative case