Spain navy

The Navy is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces. It is one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. Its beginning dates from the last years of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th century, when the great Hispanic kingdoms of Castile and Aragon were united under the Catholic Monarchs.

The Spanish Navy has played a decisive role in the history of Spain, particularly in the logistical and defensive fields during the time of the Spanish Empire. Among the great achievements of the Navy are the discovery of America[citation required], the first circumnavigation of the world by Juan Sebastián Elcano and the discovery of the maritime route between Asia and America by Andrés de Urdaneta. The Spanish Navy was the most powerful in the world [citation needed] since the century XVI until the end of the 18th century and continued to be a world reference naval force until well into the 19th century.

Today the Spanish Navy is one of the most important in the world, and one of the only nine naval forces on the planet capable of projecting a significant level of force in its own hemisphere. Its main bases are in Rota (Cádiz), Ferrol (La Coruña), San Fernando (Cádiz), Cartagena (Murcia Region) and Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. In 2017, the Spanish Navy numbered around 20,000 troops.[citation required]

Historical milestones

- The Armada, heir to the marinas of Castile and Aragon, is one of the oldest in the world.

- The first to have regulations and rules for each warship that gave unity to the operation of the fleet.

- The one that made possible the discovery of America in 1492.

- The creator of the modern concept of naval convoy (Flota de Indias), in the centuryXVI.

- The first to circumnavigate the Earth: Magellan-Elcano Expedition (1519-1522).

- The discoverer of the transpacific route between Asia and America: the Tornaviage of Andrés de Urdaneta in 1565, and the establishment of the Manila Galeon.

- The creator of the first world-wide trade route (between Cadiz and Manila): the Indian Fleet in the Atlantic, and the Manila Galeon in the Pacific.

- The creator and the first to use marine infantry (1537).

- The first to use frigates at the end of the centuryXVI during the war of the Eighteen Years.

- The creator and first to use the Cannon Lancha (Antonio Barceló in 1779)

- First round of the world by an armoured ship carried out by the Numancia armoured frigate (1865-1867).

- The first to have a destroyer in service (1887). The Destructor, who named the entire saga, was designed by the Spanish naval officer Fernando Villaamil in 1885.

- The first to have a torpedo submarine invented by Isaac Peral in 1888 (the submarine) Peral).

- Creator of the modern concept of amphibian disembarkation (with chariots of combat and a unified command for naval, land and air forces) put into practice in the landing of Alhucemas, resulting in absolute success and ending the war of the Rif (1925). The officers in charge of planning the Normandy landing (especially the most responsible General Eisenhower), which was the beginning of the end of the Second World War, studied in depth the strategy already employed by the Spanish Navy two decades earlier.

- The first ship in the world to use vertical take-off planes, in particular the Harrier AV-8A "killer" in aircraft carriers, in this case in the Give it up. (R-01) (ex-USS Cabot). This practice was then extended to other countries, in particular the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, Italy, India and Thailand. Currently Spain continues to operate with evolved versions of this type of V/STOL (Harrier II) aircraft.

History

The origins

The Navy was born from the union of the navies of the Crown of Castile and the Crown of Aragon. The navy of Aragon was a Mediterranean navy, which preferred the galley and its derivatives as combat ships, while the Atlantic navy of Castilla preferred armed ships, that is, without oars, with sail propulsion only.

This union took place in the times of the Catholic Kings, being the first Italian campaign of the Great Captain, in which the Sicilian galleys participated together with Cantabrian ships, his first war operation.

In these early days, the Spanish Navy, as in other European countries (except the Republic of Venice), did not exist in the sense that we understand it today, that is, made up of ships belonging to the State and specially made for war. Due to the privateers and the insecurities of navigation, all the ships carried cannons and weapons. When they were required by the king for war, commercial cargoes were exchanged for military cargoes, and their shipowners and crew were paid by the Crown.

In addition to the militarized merchant ships, there were also individuals who put together combat flotillas, dedicating themselves to privateering until the king requested their services.

The king named the commanders of the squadrons thus formed, in which his troops embarked. The naval combat of the time differed little from the terrestrial one, since boarding and hand-to-hand combat were sought, making relatively little use of artillery.

Interest in galleys was lost (later recovered) to the benefit of ships, carracks and caravels. At the end of the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, only four galleys remained in the Granada coast guard to support the other ships in summer.

Birth of the Navy

The history of the Armada can be dated to the last years of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th century, when the two kingdoms (Castile and Aragon) were united in fact, although not yet in law. At that time there was no centralized Navy and this was not achieved until the arrival of the Bourbons. However, there were more or less permanent military fleets that, when necessary, met to fulfill a certain mission.

The preliminaries of this incipient joint Armada can be found in the first and second expeditions to Italy and the actions of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, the Great Captain, in 1494; but perhaps the first major joint action of the two navies in a naval action was the battle of Mazalquivir in 1505.

In that battle, which began the Spanish campaign for North Africa, the organization and planning was the work of Fernando el Católico, King of Aragon, but the main promoter and even financier was Cardinal Cisneros, authentic guarantor of the last Wills of Isabella the Catholic. For different reasons, both Castilla and Aragón needed to control the southern shores of the Mediterranean, once again making the phrase "they were one will in two bodies" true.

After this conquest, the falls of Berber cities continue. From then on, Cardinal Cisneros continued to encourage and lead, but now it is Pedro Navarro, from Navarra, who commands the fleet. Thus, the sources say:

The corsairs of Berberia were treadingly stealing the coast of Granada, because they were very good interests of the assaults they did, and they were worth the country's natural Moors. The king commanded that Count Pedro Navarro should go out against them, who was one of the great captains who were born in Spain.

Under the orders of Navarro, the embryo of what would become the Navy continued its conquests:

- The Duke of Medina Sidonia had already done with Melilla in 1497.

- Vélez de la Gomera's pelon falls in 1508.

- Oran is taken in 1509 taking the same 70-year-old Cisneros on the expedition. In the conquest of Oran, the Navy played a key role in carrying out an attack combined with the disembarked ground forces. 300 Christian prisoners were rescued and a great slaughter was carried out with the enemies.

- Algiers lends vassals in January 1510 and allows to lift a fort at the entrance of their port.

- Dellys, Mostaganem and Sargel also become vassals with similar conditions.

- The fleet takes Tripoli on 25 July also 1510.

These campaigns have always been presented as the continuation of the Reconquest and, according to Ramiro Feijoo, they were, but with a defensive nature. It was not intended to conquer the entire Maghreb, but rather to secure the Iberian and Italian coasts from the continuous Berber attacks. At the same time, he shows that the Navy, like any other of the time, did not have enough technology to defend the coastline from attacks; it was an instrument to conquer the privateering places and thus defend the territories.

Once again the "Armada" had a great protagonist with Carlos I and his attack on Tunisia.

Due to a series of events, the coasts of Italy and North Africa were left unguarded and Barbarossa devastated the Italian and North African coasts, driving the Spanish from Tunisia in 1504. This corsair was considered a hero by his Muslim contemporaries and also Christians who praised his career. For example, the Abbe de Brantone, in his book on the Order of Malta, wrote of him: "He had no equal even among the conquerors of the Greek and Roman. Any country would be proud to be able to count him among his children ».

In 1535, Charles V directed a letter to assemble a fleet that, in addition to the 45 ships and 17 galleys of the Marquis of Vasto, would add the 23 caravels that Andrea Doria would bring from Genoa. To this contingent the Pope added nine galleys, the Order of Malta another six and Portugal a galleon. To these one hundred ships Carlos V brings the entire Spanish fleet from Naples, Sicily, Biscay and Malaga.

On this occasion, the army assembled by the emperor landed 25,000 men, including 4,000 veterans of the wars in Italy, 9,000 newly recruited, 7,600 Germans, and 5,000 Italians. As in the case of the Armada, the forces were Spanish (the Crown of Castile paid the entire army).

Finally, the imposing fortress of La Goleta and the cities of Tunis, Bizerte, Bugía and Bona fell into Spanish hands.

In 1541 the emperor tried to put an end to the Barbary problem with the capture of Algiers, his last bastion in the western Mediterranean, but this time the imperial Navy was dispersed by tempests and storms, and the forces already disembarked had to withdraw quickly.

At that time, the power of the Spanish fleets rested on the rowed galleys, heirs to the ships of Antiquity, and would continue to be so for almost the entire century. However, in the taking of Tunisia there are already signs of the new times. The new ships, larger than those used by Christopher Columbus forty years earlier, were already equipped with cannons and two castles (the one at the bow and the quarterdeck at the stern) and could transport 150 sailors and 500 soldiers over short distances. But without a doubt the novelty was the galleon, even bigger and much more armed than the ship, which would later be the spearhead of the Navy.

Both the ship and the galleon were ships with a more rounded hull and three masts (mizzen, foremast and main). The first was a derivative of the carrack with more artillery and the second, a response to the waves of the Atlantic that the ships could not easily overcome. Its artillery and navigation advantages were not very great in the Mediterranean, but they were in the new scenario that would soon appear to be the most important.

The importance of these two types of ships began to be seen when the first French pirates, supported and advised by renegade Spanish pirates, discovered some of the important shipments of metals and spices from America, as will be seen later.

The ships turned out to be good transport vessels, as evidenced by the fact that only the cargo of spices brought by the ship Victoria under the command of Juan Sebastián Elcano more than covered the expenses of the entire expedition of Magellan (five ships in total). For their part, the galleons demonstrated their navigation possibilities on voyages such as the one made by Miguel López de Legazpi in the conquest of the Philippines and the return of the galleon San Pedro to Mexico, which broke the saying of the Pacific ("You will go but you will not return").

Although the power of the Spanish ships was clear from the beginning of the XVI century, it is in these years that harvests began his most important achievements, such as the circumnavigation of the world, the conquest of the Philippines and the unwavering protection of the fleets of the Indies, despite the fact that American and English cinema and literature have shown otherwise.

In 1571 the best known success of the Spanish Armada in all its history took place: the battle of Lepanto. 70 Spanish galleys from Spain itself, Italy and Flanders, nine from Malta, twelve from the Papacy and 140 Venetians were concentrated in the port of Messina (Sicily, Italy), forming the Holy League. The force was led by Juan de Austria with insignia in the Real, and among the main commanders were Álvaro de Bazán, Andrea Doria and Luis de Requesens. On October 7, the battle took place, in the gulf of the same name, against 260 Ottoman galleys. After hours of fighting, in which Spanish and Venetian veterans assault Turkish ships and fight over them hand to hand, only 45 Ottoman ships manage to escape.

This victory halted Turkish naval power and the Muslim advance, mainly in the western Mediterranean. Although in reality, the Ottoman Empire did not have a hard time recovering from the defeat as far as the ships are concerned.

The Navy of Biscay

As a consequence of the Discovery of America, relations between Spain and Portugal worsened. The King of Portugal considered that, by virtue of the Treaty of Alcáçovas, the newly discovered lands belonged to him, and in the Spanish court there were reports that an armada was being prepared in Lisbon, for which the Catholic Monarchs came to fear Portuguese attacks. to the second expedition of Columbus.

To remedy this situation, the kings commissioned from Barcelona Dr. Andrés Villalón, alderman and member of the Royal Council of Their Highnesses, to urge the completion of an oceanic armada that had been being prepared since mid-1492. The royal objective was concealed saying that it was about fighting piracy. With royal permission, Villalón, in July 1493, entrusted this task to Juan de Arbolancha from Bilbao in Bermeo. The navy was known as the Armada de Vizcaya, because it was formed in Bermeo with ships and crews from Biscay (in the broad sense, that is, Basques). At the end of June Íñigo de Artieta, appointed Captain General of this armada by the kings, assembles the ships in Bermeo and at the end of July, the armada leaves for Cádiz, where they arrive at the beginning of August.

This navy was made up of a carrack of 1000 barrels, commanded by Íñigo de Artieta, four ships, of between 405 and 100 barrels, commanded by Martín Pérez de Fagaza, Juan Pérez de Loyola, Antón Pérez de Layzola and Juan Martínez de Amezqueta, and a caravel for liaison and exploration tasks commanded by Sancho López de Ugarte. It carried almost 900 men. The carrack had 300 men, the majority from Lequeitio, the ship of Martín Pérez de Fagaza, 200, the majority from Bilbao, Baracaldo and other places in Vizcaya, those of Juan and Antón Pérez de Layzola, 125 per ship, almost all from Gipuzkoa, and that of Juan Martínez de Amezqueta, 70. In the caravel there were 30 men. The cost of the army was 5,854,900 maravedis. Crews consisted of approximately one seaman for every two men of war.

Although it was considered that the mission of this navy would be to escort Columbus's ships from their departure from Cádiz until they were well into the ocean, to protect them from attacks by Portuguese ships prepared to head towards the discovered lands, in August 1493, when the kings learned from Columbus that the Portuguese ships were not going to sail, she was commissioned to transfer King Boabdil and his court from Adra to the African coast. Upon her return, she is ordered to prepare a trip to the Canary Islands, which she does not make.

After the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas with Portugal, the navy was no longer necessary, so in the summer of 1494 its dissolution was ordered. But the situation in Italy makes it necessary again, so the dissolution does not take place, and the army, increased by 7 caravels, goes to Sicily to join the 20 ships that were there.

The Indies Fleet

In August 1543 an ordinance was promulgated according to which two annual fleets were established. The first was called Nueva España and left from Sanlúcar de Barrameda (at the mouth of the Guadalquivir) to the Greater Antilles, from there to Veracruz in Mexico to pick up its cargo and take it back to the Peninsula. The second was called Tierra Firme and its first destination was the Lesser Antilles, from where it continued to Panama between July and August.

These fleets were made up of 30 or 35 ships, of which at least two were galleons, one for the fleet commander and his staff (called "Captain") and the other for the admiral (for which he received the name "Admiralty"). Both ships had four iron cannons, eight bronze cannons and 24 smaller pieces. The rest of the ships were equipped with two cannons, dozens of arquebuses and various white weapons of different types.

These galleons were often insufficient to guarantee the safety of the cargo, so both fleets were provided with an escort made up of eight or ten galleons. For this reason the escorted fleet was called the “galleon convoy”.

The information and security services were excellent, according to J. B. Black. Before leaving for the Indies they were checked three times and awaited orders away from the coast to prevent pirates, renegades or Moors from boarding, who were prohibited from emigrating to America. Communication between the captain and the admiral was carried out periodically by means of fast ships. Upon sighting land, the ships could not anchor to descend to land except in cases of extreme necessity and for a period not exceeding 24 hours. The penalties for violating these orders were strong, and could go as far as the death penalty. In addition, before their departure, a fast ship was sent to inform the Peninsula of their expected arrival and the cargo they were carrying. Information on the weather and the possible presence of pirate forces was also collected. In case the situation required it, the two fleets could travel together or delay their departure or send the cargo in three or four zabras, ships of about 200 tons, fast and well armed that could make the trip in 25 or 30 days in instead of the usual merchants or, in extreme cases, give up making the trip until the following year.

These fleets used to carry gold from Mexico and/or Peru and silver from Potosí. However, they were not the only high-value products; its holds also carried precious stones, pearls obtained from the Venezuelan and Colombian Caribbean coasts, some spices, such as vanilla, and highly coveted dyeing plants, such as Brazilwood and campeche wood. These treasures made any ship separate from the The rest by a storm, for example, was a highly coveted prey, and its capture allowed to feed the legend of large captures by pirates, which in reality only happened exceptionally. Thus, the Fleet of the Indies can be described as one of the most successful naval operations in history. In fact, in the 300 years of existence of the Fleet of the Indies, only two convoys were sunk or captured by the English.

Among the Spanish historical figures who participated in the Carrera de Indias, the privateer and merchant Amaro Rodríguez Felipe, better known as Amaro Pargo, stands out. His participation in the race to the Indies began in the two-year period 1703-1705, a period in which he was the owner and captain of the frigate El Ave María y las Ánimas, a ship with which he sailed from the port of Santa Cruz de Tenerife to that of Havana. He reinvested the profits from the Canarian-American trade in his estates, destined mainly for the cultivation of the Malvasia and vidueño vine, whose production -mainly that of the vidueño- was sent to America.

The Atlantic as a new setting

During the reign of Felipe II, Francisco Pizarro shows that Peru was not a myth and that it was enormously rich in precious metals. This discovery would join the findings in Mexico and Bolivia (with the famous Potosí mines).

Despite the fact that for many years the Spanish monarchs tried to keep what was discovered in America a secret, already in 1521 French pirates under the command of Jean Fleury managed to capture part of the famous “Moctezuma Treasure”, opening a whole new way for assaults and boardings in search of fabulous loot. Given the relatively immense wealth found, the example soon spread among the French and the stalking and assault of Spanish ships increased.

Although the catches were negligible for the many riches brought from the Indies, the importance of these shipments was too great not to protect them. Thus, Spain began to have two different types of fleets. On the one hand, the Mediterranean, in which galleys moved by rowers proliferated (obsolete ships, but that victory in battles like that of Lepanto seemed to deny). On the other, the Atlantic, made up of ships and galleons. Although the galleys remained in force for many decades, it was the Atlantic fleets that really had the favor of Felipe II and his heirs; Juan de Austria himself had to leave his ships anchored due to lack of budget after the successful victory at Lepanto.

At that time, the Atlantic fleet had the best techniques and the most recent advances in navigation; His plans, design and construction of ships and galleons were a closely guarded secret. So much so that it has not reached our days, as demonstrated by the fact that none of the replicas made on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the discovery of America managed to match the times achieved by Columbus. Consequently, the transport of merchandise was assured if there were no storms that would sink many ships. The cargoes were carried by two annual fleets that departed mainly from Cartagena de Indias and were escorted by a crew of ships and especially galleons.

English pirates, such as Francis Drake or John Hawkins, have always been presented in England as national heroes and a true ordeal for the coffers of the Spanish crown. But more detailed studies of this piracy indicate that the power of the Spanish fleet was overwhelming over all others. An example is the defeat suffered by those two pirates at the hands of the New Spain fleet in the battle of San Juan de Ulúa in 1568, from which the English were only able to save two ships.

The superiority that a formation of galleons had over any navy was evident with the first combats in 1588 against the English ships of the Great and Most Happy Armada, which after its failure the English ironically nicknamed the Invincible Armada , a name it never officially had. On that occasion it was not a pirate fleet, but all the English forces fighting for the survival of their own country. Even with all that they could not break the formation of the Armada or stop it. Only after disrupting the ships with fireships and the support of the Dutch ships, in addition to unfavorable weather, did they manage to cause damage to the Spanish ships and galleons, but only in four ships (one galley, one ship and two galleons), with 800 casualties (out of a total of 130 ships and almost 29,000 men). This is not a revisionist thesis nor does it mean that the Invincible did not fail, but it does mean that the action of the English squadron did not cause the disaster.

After this victory, optimism spread in the court of Elizabeth I, and even euphoria, which led them in part to organize the Counter-Armada. The English considered it possible to invade Spain through La Coruña, but the facts proved that they were wrong. The men that Álvaro de Bazán commanded before his death and the inhabitants of the cities awaited them and inflicted a resounding defeat on them, first in La Coruña and later in Lisbon, Cádiz and Cartagena de Indias. The English also lost 20 ships and 12,000 of their men. The difference with the Spanish casualties is that this figure was more than half of the soldiers and sailors sent (20,000 in total), the majority under Spanish guns. The private council of Elizabeth I in a reserved report described the operation as follows:

The issue of the Counter-Armed has been not only a financial catastrophe but also a strategic one.

Philip II sent two more armadas against England, which also failed due to weather. But this is not something unique: Japan was never invaded by the Mongols thanks to the so-called Divine Wind (Kamikaze, in Japanese).

Hostilities continued between the two nations, which were increasingly exhausted. According to some historians, such as Mariano González Arnao, if Felipe II did not conscientiously plan the invasion of England, he was rather waiting for divine intervention in a cause that should also be his. If he had drawn up a meticulous plan, as he was, the results would have been very different, since England really had very few forces to defend itself.This seems to be confirmed by facts such as:

- In July 1595 Captain Carlos de Amésquita spent seven days with his three galleys disembarked in English lands without finding excessive resistance.

- With Philip III, John of the Eagle disembarked 3,500 infants in Kinsale and held there for four months, until he finally retired in February 1602.

By the end of the 16th century, both nations were exhausted. Spain had achieved victories against the Duke of Essex and in the Azores against Raleigh, defeating the English attempt to conquer the Isthmus of Panama in 1596, a resounding failure that cost the lives of the two best English sailors of the time, sir Francis Drake and John Hawkins. For their part, the men of privateer George Clifford, third Earl of Cumberland managed to seize San Juan de Puerto Rico in 1598, although they had to withdraw after a few months. Faced with this situation, with a very changeable fate of the war and with the death of Elizabeth I, Spain and England rushed to sign the Treaty of London in August 1604.

World naval power until the 18th century

Despite the erroneous notion that Spain began to lose its world naval supremacy after the defeat of the Great and Most Happy Armada in 1588, a fallacy essentially spread by English or Anglophile historiography, it is a proven fact that Spanish naval power Not only did it not diminish then, but it lasted until the 18th century, which allowed Spain to maintain communication with its overseas provinces and territories through its Indies Fleets (America) and the Manila Galleon (Philippines). In 1714, already under the Bourbon dynasty, a Secretariat of the Navy was created, which promoted the reform, modernization and expansion of the Navy in the XVIII, necessary to ensure communication with Spanish overseas territories, frequently threatened by corsairs and foreign powers.

The British Navy suffered the greatest defeat in its history in 1741 during the siege of Cartagena de Indias (see Guerra del Asiento), when a huge fleet of 186 English ships with 23,000 men on board attacked the Spanish port of Cartagena of the Indies (today Colombia). This naval action was the largest in the history of the British Navy, and the second largest of all time after the Battle of Normandy during World War II. After the defeat, the English prohibited the dissemination of the news and the censorship was so strict that few English history books contain this episode of its history.

A very common historiographical error is the one that says that British naval superiority completely prevented American trade, but in reality the fleet of galleons that linked Spain with America was lost only four times over 300 years. In this sense, the episode that took place in 1780, during the reign of Carlos III, when Admiral Luis de Córdova captured a large English convoy at Cape San Vicente, where the battles of Cape San Vicente took place, is not known either.. Upon spotting the Spanish squadron (with some French units) under the command of Luis de Córdova, instead of facing the convoy escort, it fled, and the merchantmen, some of them armed with more than 30 cannons, they hardly resisted. The defeat, on this occasion of His Gracious Majesty, was double, in the sense that not only were those ships lost, but all of them went on to join His Catholic Majesty's Royal Navy, giving years of good service and even carrying up to 40 guns.

Philip V and his ministers reform the Navy

The desire of the other powers to reduce the power of Spain and keep some of its possessions could not be settled with the royal will, so the War of Succession was almost inevitable. This war and the negligence committed in it led to new defeats for the Spanish arms, even reaching the peninsular territory itself. Thus occurred the loss of Oran, Menorca (which would not be definitively recovered until 1802) and the most painful and prolonged, which was that of Gibraltar, which the British treacherously seized. Only 80 soldiers and 300 militiamen, with little or no military training, endowed with 120 guns (of which a third were useless) defended it, against an Anglo-Dutch fleet totaling 10,000 men and 1,500 guns, supported by a battalion of 350 Catalan soldiers in favor of Archduke Carlos of Austria (who disembarked on a beach known since then as Los Catalanes beach). After five hours of bombing, the square surrendered, but not to the United Kingdom but to Carlos III of Spain, as the archduke called himself, in whose name it was occupied. Said appropriation, described by historians of the United Kingdom itself as an "act of piracy", was contrary to all law, since England was not even at war with Spain, but was simply intervening in favor of one of the pretenders to the throne. Felipe V, eager to achieve the recognition of the United Kingdom as King of Spain, agreed through the Treaty of Utrecht to perpetuate this situation.

Philip V was not prepared to lead the largest kingdom of that time and he knew it; but he also knew how to surround himself with the most prepared people who brought a project, and the Navy —it is the first time it can be called that— was one of the points where the most successes were achieved.

The first of the reformers was José Patiño. This Italian of Galician origin, one of the best naval technicians of the 18th century, began by restructuring the fleets and small navies into a single, common institution. Likewise, he founded new shipyards, such as Cádiz or Ferrol, and set up, together with the enlightened minister Zenón de Somodevilla, Marquis of La Ensenada, the important arsenals from which cannons, ammunition, fittings and other items could come out to be able to assemble all the ships that they had to be built. Patiño managed to put 56 ships afloat and build 2,500 new guns. Patiño's work has always been remembered by the Navy, to the point that, in the 20th century, one of the logistics supply ships was named after him.

The Marquis de la Ensenada, another of the great reformers of the Navy, aware that the Spanish Navy was beginning to be outdated, would advise in 1748 that the marine expert Jorge Juan y Santacilia travel to the United Kingdom to spy on and discover the new British naval techniques, and some of these foreign skilled technicians would be hired by the Crown to work in Spanish shipyards. This is how he planned and made the construction of a large fleet for Spain a reality, some of whose ships would be at the forefront of naval engineering at the time, such as the Montañés line ship. The Navy counted an increase of at least 60 ships of the line and 65 frigates ready for operation. Likewise, Ensenada raises the Army to 186,000 soldiers and the Navy to 80,000.

During the rest of the century, the pre-eminence of the Spanish Navy, and especially in the Atlantic, was manifest, as demonstrated, among other occasions, in the so-called War of the Asiento, where one of the greatest admirals ever to have stood out. had the Spanish Navy, the Gipuzkoan Blas de Lezo. Another outstanding sailor and captain general of the Navy of this period was Don Luis de Córdova y Córdova.

The Havana arsenal was the main navy shipyard during the 18th century with 197 ships built in 97 years. From the Nuestra Señora de Loreto, with 12 guns, to the Santísima Trinidad (1769), originally with 120. Cuba's wealth of natural resources and its strong defenses made it an ideal site for the construction of new boats. Launched in 1739, the 70-gun Princess fought alone against three British ships of similar size in 1740. This was the first time the British realized the quality of Spanish design and construction. This ship, already old when she was captured, spent another 20 years in service in the British Navy.

The arsenal of El Ferrol was the second most important Navy shipyard during the XVIII century, it built 50 ships between 1720 and 1790 including the 112-gun San José. Captured by Nelson at Cape St. Vincent and renamed San Josef, she was Nelson's first flagship. That a prominent commander chose a foreign ship as his flagship is further evidence of the quality of Spanish ships. In 1735 the 74-gun Guerrero was launched, becoming the longest-serving warship of the line in the age of sailing with a record of 89 years of continuous service. An example of design and quality.

Regarding the Spanish marine infantry of the 18th century, two names stand out for their courage and heroism: Captain Correa and Ana María de Soto. Captain Antonio de los Reyes Correa, risking his life and that of his family in one of the greatest and noble acts of the Spanish marine infantry managed to prevent the English invasion of Puerto Rico in 1702, which earned him to be decorated by the King Felipe V in 1703 and being promoted to Captain of the Infantry. His feat prevented the British invasion of Puerto Rico and the catastrophic consequences it would have had for Spain. Ana María de Soto, posing as a man under the name of Antonio María de Soto, enlists in the 6th company of the 11th Marine Battalion in 1793, being discharged with a pension and honors as sergeant in 1798 when it was discovered that she she was a woman She was the world's first female Marine.

From the last period of the century, it is worth noting the sailors and naval engineers José Joaquín Romero y Fernández de Landa and Julián Martín de Retamosa, promoters of some of the best ships of the line of their time. In 1797 the Navy had 239 ships, of which 76 ships of the line and 52 frigates, the highest figure of the entire century.

From the Battle of Trafalgar to the death of Ferdinand VII

On October 21, 1805, the Franco-Spanish fleet forced into battle by the French Admiral Villeneuve, against the advice of the Spanish high command headed by Federico Gravina, was severely defeated at the Battle of Trafalgar. After the massacres perpetrated during the French Revolution, the quality and capacity of the French officers and admiralty had been seriously affected; likewise, many of the Spanish crews enlisted by the Napoleonic command were land soldiers, peasants and even beggars recruited for the occasion, in contrast to the professional British crews, well trained and who had experienced numerous naval actions. The loss of many experienced sailors in a yellow fever epidemic in 1802-04 had led to hasty action mustering such a dwindling force. In contrast, Nelson's daring tactics took advantage of the difficulties and lack of foresight and leadership of the French, led by Villeneuve, who had already shown more than enough inability to command in the embarrassing defeat at the Battle of Finisterre three months earlier.

Contrary to the general opinion of British historiography and also part of Spanish historiography, literature and imaginary, the Battle of Trafalgar did not mean the collapse of the Spanish Royal Navy, and proof of this are the two resounding British failures in 1806 and 1807 during the English invasions of the Viceroyalty of the Río de La Plata in which the sailor Santiago de Liniers would stand out. In 1808 the Royal Navy still had 43 ships of the line and 25 frigates. Actually, there would be numerous ships such as the Santa Ana, the Príncipe de Asturias and others that would rot and collapse due to the lack of hulls in different arsenals, since these industrial establishments, once among the first in the world, were progressively abandoned and left in ruins., due to the collateral and undesirable effects of the Napoleonic invasion and the War of Independence, which would destroy and ruin Spain, and its Army and Navy.

In 1817, Minister Vázquez Figueroa drew up a Naval Plan for the reconstruction of the fleet, whose intention was to acquire 20 ships, 30 frigates, 18 corvettes, 26 brigantines and 18 schooners. Six ships were acquired as an initial consignment to France, but the minister was later removed by King Ferdinand VII, so his plan was not fulfilled and, ignoring the Navy commanders, second-hand Russian ships were acquired from the Navy of the Tsar, which was a scandal and surely one of the worst investments of the Navy. The ships were rotten and in terrible seaworthy conditions, so they were soon decommissioned.[citation needed]

After the losses that occurred during the Spanish-American Wars of Emancipation, the Navy would find itself in the worst situation in its history. In 1824, in a first and timid effort to regenerate the Navy, three 50-gun frigates completed in 1826 would be commissioned, proving excellent throughout their operational lives. In September 1833, when Ferdinand VII died, the Navy only had three ships, five frigates, four corvettes and eight brigantines, with the arsenals in a dilapidated state.

In 1834, José Vázquez de Figueroa returned to his position as Minister of the Navy, but had to deal with the First Carlist War. In those years, steamships began to be introduced, forcing the purchase of ships abroad.

Loss of overseas possessions and reorganization of the Navy

The other great event of the XIX century for the Navy, in addition to the Spanish-South American War (1865-1866), was the Spanish-American War of 1898. The Navy was affected by the long economic and political crisis suffered by Spain at the end of the XIX century . This situation was skillfully used by the American leaders, who saw in this an opportunity to present their country to the world as the newest world economic and military power. The United States naval command had previously studied the difficult time that Spain was going through and its low response capacity, even more increased by the remoteness of its bases.

The rapid attack by the Americans fulfilled these strategic plans and achieved rapid battlefield effectiveness despite the great efforts and great courage of the Spanish naval forces. It was the meeting of the old great power, at that time in crisis, and the new power on the rise, presenting itself internationally with a spectacular action. And in truth it meant the great impulse for the American nation, but for its antagonist it meant the accentuation of a crisis that would not be resolved until the second half of the century XX, when the Spanish Navy managed to reorganize itself, recover its forces and once again rank among the most important navies in the world.

After the disaster of 1898, Spain lacked international support and it was feared that some power would take advantage of Spanish weakness to conquer the Canary Islands, the Balearic Islands, Ceuta, Melilla or any of the African possessions. For this reason, as a result of the disaster of 1998, a new naval policy was established, whose objective would be to defend the coast of Spain, its trade and its fishing, and to ensure its position in the western Mediterranean and in the Strait of Gibraltar, where Morocco would occupy a place priority, especially after the Algeciras conference of 1906 that paved the way for the establishment of a protectorate over its northern strip.

In 1900, by Decree of May 18 of the Ministry of the Navy, the situation of the Navy ships at that time was technically described and 25 units were decommissioned as they were considered ineffective. In summary, the panorama that emerged pointed out in that Decree of 1900 was devastating, since it only considered 2 ships suitable for modern warfare at that time (the battleship Pelayo and the cruise ship Carlos V). The armored frigates Numancia and Vitoria were of little military value (and also had to be decommissioned with the next careening or due to a major breakdown). Other ships (the cruisers Río de la Plata, Extremadura, Infanta Isabel and Lepanto, the Álvaro-class gunboats of Bazán, the gun-torpedo boat Nueva España, the corvette Nautilus, the Furor-class destroyers and the Destructor, along with other smaller ships) were from null or almost null military value that could be conserved, in general, due to their speed as warnings, for service in overseas colonial territories, as training ships or possible internal civil conflicts. Also saved were the yacht Giralda, which would become a royal yacht soon after, and the steamer Urania as a survey vessel. All the other ships that the Navy had at that time were simply worthless and it was better to decommission them so as not to waste the budget.

No one doubted the need to modernize the Navy, but many questioned whether Spain had the technology and industry required to undertake this plan. The cooperation of the United Kingdom, with the aim of providing the Navy with modern deterrent elements against German ambitions, was reflected in 1907 with the visit to Cartagena of King Edward VII and the signing of the Cartagena Agreements between Spain, the United Kingdom and France.

The first measures were taken in 1907 by the government of Antonio Maura (who as president of the Spanish Maritime League was a firm supporter of giving Spain a powerful Navy) and were the work of his Minister of the Navy, the captain of the ship José Ferrándiz, who in November obtained the approval by the Cortes of the Law for the reorganization of the Navy services and naval armaments. In it, the new naval construction plan was established, which consisted of three battleships, of the British Dreadnought model and three destroyers, in addition to 24 torpedo boats and 10 fishing surveillance vessels. The British willingly accepted to transfer technology, designs, specialized personnel and even materials that were not manufactured in Spain.

The battleships were slow to build (the España, which sank in 1923, was delivered in 1913; the Alfonso XIII (renamed España in 1931) in 1915 and the third, the Jaime I, in 1921) and soon fell behind because at the time of its delivery the Super-dreadnought battleships had already been developed, with displacements of 25,000 tons, 29 knots of speed and 380 mm artillery, in front of the 15,000 tons, the 20 knots of speed and the artillery of 305 of the battleships of the previous model. "It seems that the squadron planned to be completed in 1916 had not assimilated all the lessons of the Russo-Japanese war and could not have served even the slightest in the case of a belligerent Spain (see Spain in World War I#Armada). What is more serious is that it did not serve to protect Spanish trade during the Great War. The ships did not carry out anti-submarine surveillance patrols, remaining moored in their ports at a time when the merchant fleet on which Spain depended needed a navy to defend it".

The policy of naval rearmament was continued by Vice Admiral Augusto Miranda y Godoy, Minister of the Navy between 1913 and 1917, whose plan approved in 1915 consisted of the construction of four fast cruisers (which would be the cruiser Méndez Núñez, the cruiser Blas de Lezo, the cruiser Almirante Cervera and the cruiser Príncipe Alfonso, renamed Libertad by the Second Republic), six destroyers (the Alsedo, the Lazaga and the Velasco, plus three of the new type Churruca), three gunboats (Dato, Cánovas and Canalejas) and 28 submarines (including six Class B and six Class C). Economic problems caused the deliveries of the new units of the Miranda program to be delayed until the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera (1923-1931).

At that time, the only active experience of the Spanish Navy was during the Moroccan war, in which the most important operation was the famous landing of Al Hoceima in September 1925, the first air-naval landing in history, with the important participation of the seaplane carrier Daedalus.

During the Primo de Rivera dictatorship, the Minister of the Navy, Rear Admiral Honorio Cornejo y Carvajal, expanded the Miranda program with a new cruiser (which would be the Miguel de Cervantes cruiser) and three more destroyers of the Churruca (the José Luis Díez, the Almirante Ferrándiz and the Lepanto). These were built quickly and entered service around 1930. A longer-term plan called for the construction of three new Washington-type cruisers (far superior to previous types), two of which were finished at the start of the Civil War. Spain (the Canarias and the Baleares) and ten new destroyers also of the Churruca type (the Churruca, the Alcalá Galiano, the Almirante Valdés, Admiral Antequera, Admirante Miranda, Gravina, Escaño, Císcar, Jorge Juan and Ulloa) that entered service shortly before or during the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939.

Spanish Civil War

During the Second Spanish Republic (1931-39) the Navy became the Navy of the Spanish Republic. In the same way as the other two branches of the Armed Forces of the Spanish Republic, in the history of the Navy of the Republic there are two clearly differentiated phases:

- La Fase de preguerra civil, from the declaration of the Republic on April 14, 1931 until the coup d’etat of July 18, 1936, which fractured the Spanish military institution.

- The situation following the coup d’état of July 1936 that led to the Spanish civil war, when the majority of the fleet remained loyal to the government of the Republic, after the crews were replaced with their commands and formed committees in these. Even so only 5% of the high-ranking officers remained faithful to the Republic.

The National Navy of the rebel side carried out with increasing success the primary function of a navy at the beginning of the XX century which was to block their maritime routes, their ports and prevent their movements on the coast.

By the end of the war, a total of eight Republican main fighting units had been sunk; the surviving ships were integrated into the navy of Francoist Spain. Most of the documents related to the Navy of the Republic of Spain are currently in the General Archive of the Navy "Álvaro de Bazán".

The Navy during the Franco dictatorship

In 1939 Franco's National Navy incorporated the ships of the Republican Navy and returned to the original name of the Spanish Navy.

During the dictatorship of Francisco Franco (1939-1975), the Spanish Navy, like the other two branches of the Armed Forces, traditionally maintained its own ministry, the Ministry of the Navy. After the Spanish Civil War and Until the end of the 1950s, the Armed Forces were very poorly organized and even less prepared for any other action than suppressing local insurrections (the so-called "internal enemy"). Thus, the military extolled the virtues of the horse against tanks and the value of equipment. This was the case due to the authoritarian government's own policy. Modern, well-formed and trained armies required contact with free and democratic nations, which could be dangerous for the regime. For years they penetrated deeply into the FF. AA. Phrases like the one pronounced by Franco that, faced with the danger of invasion, the Spaniards had "the heart and the head" to oppose planes, tanks, destroyers and battleships... Deep down they longed for the equipment of other nations.

On the other hand, the possibilities of possessing state-of-the-art technology were very low internally, and even more so abroad, since Spain only had access to relatively modern weapons and weapons systems on a few occasions.

These two causes meant that Spain had a very poor Navy, from the point of view of European standards.

Until the 1950s, the ships available to the Spanish Navy had technology similar at best to that of the World War II navies. The same happened with the planes of the Spanish Air Force.

The situation gradually improved from the mid-50s, when the pressure from other countries to keep Spain isolated began to diminish. Thus, in 1954, at the top of the Franco dictatorship, it was already suspected that the Western nations, and especially the United States, needed Spain in the Cold War and would allow them to acquire and build modern weapons, in addition to giving them financial facilities.

In 1953, in the middle of the Cold War and facing the danger of a Soviet attack against the United States through the Mediterranean, the governments of Spain and the US signed agreements based on which US bases were installed in Spain, under the Spanish flag and with some exclusive areas for each nation, several bases for joint Spanish-American use, in which contacts between the Spanish and American military were continuous. As a result of these agreements, up to 30 ships of the Spanish Navy were modernized. In addition, since 1954, the US lent the Spanish Navy a series of ships that, for the most part, had to be picked up by Spanish sailors in North American ports. In short, there was a modernization of the Audaz-class, Liniers-class, and Liniers-class destroyers. the Pizarro class frigates, the D class submarines, and other smaller ships (torpedo boats, minelayers, gunboats, minesweepers...). Years later, delivery of the aircraft carrier Dédalo, Lepanto (Fletcher) class destroyers, Balao class submarines, and other smaller vessels. Collaboration in the development of the Balearic class frigates.

At the same time, the Air Force begins to receive modern aircraft. Thus, in the 50s the Grumman Albatross, the Saber and the T-33 arrived, among others, In the 1960s it was the turn of the Starfighter and the Caribou, and in the 70s of the Phantom and F-5, all of them modern aircraft in their day. The delivery of these ships and planes was made mostly in the United States, where training courses were also given to train the Spanish military in the use of these new weapons, which implied stays in the US for months, and in some cases over a year.

These contacts, together with the very nature of naval and air activity, which implies contact with the outside world, made Spanish aviators and sailors acquire a good technological level and become convinced that long-term programming and plans, as well as an autonomous military development, were a necessity. Thus, in 1964 PLANGENAR was born, which was in force until the mid-1980s, after its last revision in 1976.

Modernization of the Navy after the Transition

At the arrival of democracy in 1977, the Spanish Navy had registered the following units:

- 1 aircraft carrier Dédalo (R-01)

- 5 frigates spearhead F-70 in the 31st Sculpture

- 5 Lepanto Class destroyers (Fletcher) D-20 in the 21st Squad.

- 5 destroyers Churruca Class (Gearing) D-60 in the 11th Squadron.

- 3 destroyers Class Oquendo D-40 framed two in the 11th and one in the 21st Squadron.

- 4 Class GUPPY submarines (S-30)

- 4 submarines Daphné Class (S-60)

- 4 Straight Class ties (F-60)

- 6 Lazaga Class patrollers (P-00)

- 6 Barceló Class patrollers (P-10)

- 1 Amphibious personnel transport TA-11 Aragon ex USS Noble (APA-218).

- 1 Amphibious material transport TA-21 Castilla ex USS Achernar (AKA-53)

- 1 ship disembark dique LSD Galicia L-31 ex USS San Marco (LSD-25)

- 3 landing ships LST Class Terrebonne Parish L-10

- 2 Oceanographic Ships Malaspina Class (1973)

- 4 auxiliary oceanographic ships Class Cástor (1966)

- A modern Air Force with AB-212 ASW, SH-3D, Bell AH-1G Cobra, Hughes 369 HM and V/STOL AV-8 Matador aircraft.

In PLANGENAR, the Naval Plan of the Navy of 1977 provided for the constitution of a modern combat group made up of a light aircraft carrier and at least 3 Santa María Class Frigates (F-80) (1977 execution order), whose model was the modified North American Oliver H. Perry class, increasing, among other details, the anti-submarine capacity. 4 Galerna Class Submarines (S-70) (scheduled for the year 1979) were also planned to replace the obsolete GUPPY of the S-30 Class.

The aircraft carrier Almirante Carrero Blanco (scheduled for launching in 1981) and which would eventually be named Príncipe de Asturias. It was a project abandoned by the United States Navy to have another type of light aircraft carrier (baby carrier or escort aircraft carrier in military jargon) to replace the R-01 Daedalus i> (which would be dropped in 1989).

The original project was called the Sea Control Ship (SCS) and it was actually a large cruise ship from which some STOVL planes and helicopters could take off, initially conceived to escort Atlantic convoys against the submarines of the Soviet Navy, in the event of the outbreak of World War III, quick to manufacture and cheap to maintain. This draft was taken up by the Bazán National Company, modified and widely improved until it became the Príncipe de Asturias (R11).

The F-30 Discovery Class corvettes were also under construction, with 8 planned, although the last two were finally sold to Egypt in 1982.

When reviewing the second phase of the PLANGENAR Naval Plan, in the early 1980s, the Navy decided to build a fourth Santa María F-80 Class frigate to replace the two F-30 Discovery Class corvettes sold to Egypt. Together, the Príncipe de Asturias (R-11) and the Santa María class frigates formed the Alfa Group in the late 1980s.

But 15 years later, the Navy's situation was somewhat difficult. Those that in 1977 were modern ships, at the beginning of the 90's had already exceeded half of their operational life. There were no destroyers anymore and the older amphibious ships were replaced by others of foreign origin and most of the ships were over 20 years old.

At this time the Navy had received:

- 1 aircraft carrier, Prince of Asturias (R11) to replace Give it up. (R-01).

- 4 frigates Class Santa Maria F-80 for the new 41.a Sculpture squad that replaced the 11th Squad.

- 6 Class Decked Class F-30 corvettes to replace the destroyers of the 21st Squadron.

- 4 submarines Class Galerna S-70 to replace the S-30s.

- 2 second hand amphibious assault vessels LPA Class Paul Revere L-20 requested to the United States to replace TA-11 and TA-21. They arrived in 1980.

- 1 AO Marquis de la Ensenada (A-11).

- 4 high-end patrolmen of the Class Serviola who replaced those of the Class Atrevida F-60.

- 1 BIO Hespérides Oceanographic Research Bucket (A-33) that allowed long annual campaigns in Antarctica.

Plus a few other smaller units. To deal with these problems, the Navy designed a possible plan to be endowed with the means considered necessary until the first third of the century XXI. This plan replaced the obsolete PLANGENAR of 1977 and was called Plan ALTAMAR.

The PLAN ALTAMAR of 1990 with a view to the XXI centurywas the continuation of the PLANGENAR of 1977 and came to replace those for replace the old destroyers, minesweepers and amphibious ships. The keys to this plan were:

- Not to be overly ambitious as had been previous ones, which did not happen. The Navy was very committed in their requests.

- Cover the entire supply of ships, except for corvettes, patrol boats and smaller ships.

- Relinquish two pillars considered key by the Navy: the nuclear submarines and the second carrier.

- Try to achieve maximum independence (without possible) from other nations.

- Most of the boats were joint bets. Thus, amphibious assault vessels were a Spanish-Dutch project, just like logistic supply ships; hunters were Hispanic-British, Hispanic-French submarines; however, F-100 frigates (the key to the plan and the most expensive part) were Spanish designs and developments.

- The Plan was completed in 2005, except for submarines.

However, reality showed that the Spanish economic situation gave for much more than initially budgeted. Furthermore, the political situation, which had to face the problem of giving the shipyards a workload, as well as political and other events and agreements, meant that the execution of the Plan, although it is true that in some sections it was cut, it would almost double what was initially planned, resulting in a modern and highly technical Navy.

The following were received as a result of this plan:

- 2 additional frigates Class Santa Maria F-80 for the 41st Squadron Squadron to replace the last two D-60 destroyers.

- 4 frigates Class Alvaro de Bazán F-100 that replaced the F-70s of the 31st Squadron.

- 2 amphibious assault vessels LPD Class Galicia L-50 with flooding dam for LCM plus track and helicopter hangar, replacing the Paul Revere L-20 class.

- 2 Second-hand LST Class Newport L-40 landing ships yielded by the United States to replace the Class Terrebonne Parish L-10.

- 1 combat supply ship BAC Patiño (A-14).

- 6 Segura Class M-30 of eight planned, replacing all old men in service (12).

- 4 high-rise patrollers to support the Chilreu P-60 fishing.

The Navy in the 21st century

At the turn of the 21st century, the Admiral General of the Navy confirmed that the Navy faced a totally different situation than the of the previous century, since at present the modernization and the new technology of the material predominated in it.

In 2017, an update of the analysis of a specialized page determined, according to its own criteria, that the Spanish Navy could be the tenth most powerful in the world, losing four positions compared to previous analyses. Budget cuts, the loss of the Príncipe de Asturias service and incidents and delays in the S-80 project are behind this situation.

Due to their former status as an armed force, and by virtue of Decree 1002/1961, of June 22, on maritime surveillance, the ships of the Customs Surveillance Service (SVA) are considered Navy Auxiliaries. The maritime component of Customs Surveillance is one of the most important in the Spanish State, with more than 40 vessels specialized in different tasks.

Aircraft

Squadrons

- Third squad: Formed by 7 Agusta-Bell AB 212 helicopters of 14 acquired. Initially he was engaged in the anti-submarine and anti-surface war, with 4 of the equipment with electronic warfare equipment and ELINT Elettronica Colibrí. They are currently used as assault transport for the Marine Corps. [7]

- Fourth Squad: Formed by four Cessna Citation surveillance and transport birreactors, three Citation II and one Citation VII. Their missions are maritime surveillance, liaison and transportation. [8]

- Fifth squad: Formed by 3 SH-3D/H helicopters, initially dedicated to the anti-submarine and anti-surface war, although currently more dedicated to assault transport missions with the dismantling of their electronic systems, being able to transport up to 25 Marine and SAR infants; and 3 SH-3D/H (HS.9-9, HS.9-11 and HS.9-12) specialised in early searchwater. [9].

Between December 2015 and January 2016, the dismantling and storage of the three Searchwater AEW teams existing in the Navy, proceeding to transform their platforms into a utilitarian version in the absence of helicopters for the L-61.

Defense plans to acquire ten units from the SH-60F version to progressively replace the obsolete SH-3 Sea Kings, operating since the late 1960s.

The two SH-60F helicopters received in 2018 start operating temporarily with the 10th Squad. [10].

At the same time, in December 2018 the first SH-3D received by the Navy (01-501) was released after 52 years of service. It is expected to drop one or two SH-3Ds a year along with replacement helicopters arriving 6 SH-60 F (four additional aircraft will be received up to 8 and two other spare parts units) - Sixth squad: Formed by 9 Hughes 369 HM helicopters. Initially they were acquired as anti-submarine light helicopters, but are currently used for training missions, surveillance, liaison, naval shooting correction and laser-guided lighting. [11]

- Ninth Squad: Formed by 12 Harrier AV8B II Plus and a TAV-8B bike. Air protection functions of the fleet, coverage for the Marine Corps, defence suppression and recognition.

- Tenth Squad: Formed by 12 Helicopters SH-60 B SeaHawk, dedicated to the anti-submarine and anti-surface war. They form the typical board unit of the F-100 and F-80 frigates. [12]

- Eleventh Squad: In charge of the use of unmanned aircraft and currently has eight units of the Boeing Insitu ScanEagle, as a second system was received in 2017.

Marines

Armed Protection Forces (FUPRO)

- Tercio de Armada

- South Tercio

- North

- Tercio de Levante

- Canary Islands

- Madrid Group

Special Naval Warfare Force (FGNE)

The Special Naval Warfare Force combines the potential of the old Special Operations Unit (UOE) and the Special Divers Combat Unit (UEBC) of the Navy, transforming them into a single force within the Marine Corps and based in Cartagena.

It was established on June 10, 2009, during a ceremony presided over by the Commander General of the Marine Infantry, Major General Juan Chicharro Ortega, who handed over command of the new unit to Marine Infantry Colonel Javier Hertfelder de Aldecoa, although the true creator of the special operations unit of the Marine Corps is Colonel Julio Yáñez Golf.

The creation of the FGNE is contemplated in the current organization of the Armed Forces and responds to the need to have a genuinely maritime special operations capacity. The new force constitutes the contribution of the Navy to the capacity of joint special operations (land, Navy and Air) and will report directly to the Commander General of the Marine Corps.

The members of the FGNE are qualified in techniques such as special reconnaissance, direct action and military assistance, diving with handling of explosives, parachuting, evasion and escape, ground combat, infiltration and exfiltration, personal defense, shooting precision etc The Special Naval Warfare Force now includes special naval warfare teams that participate in international missions, such as the United Nations Interim Mission in Lebanon, and the EU's Operation Atalanta to combat piracy.

Special Unit of Combat Divers

The missions entrusted to the UEBC as a Special Naval Warfare Unit before being absorbed by the FGNE were:

- Special recognition and surveillance.

- Direct action.

- Military assistance.

- It will also have the capacity to carry out hydrographic reconnaissance, submarine demolitions and CSAR missions (Combat Search And Rescue) in maritime environment.

Special Operations Unit

The Special Operations Unit (UOE) was a small but highly specialized unit, whose members, before being able to become part of it, had to pass demanding training in special combat techniques, parachuting, diving, combat in mountain etc The generic mission of the UOE was to carry out Special Operations in the maritime and maritime-terrestrial spheres in the form of direct or indirect military actions on strategic, operational or tactical objectives of high value, both in peacetime and in crisis situations or war, using tactics, techniques and procedures different from conventional forces. Success depended on the team's ability to remain undetected within its area of operations while simultaneously acquiring and transmitting information. Both the training and the objectives of the UOE have been assumed by the FGNE.

Special Unit for Explosive Disposals

The missions carried out by this Unit are the following:

- Support to the Diving Units.

- Teaching in E.O.D. Submarine courses.

- Development of methods of deactivating explosives.

- Cooperation with other deactivated units.

- Continued and up-to-date training of deactivated information and techniques in close collaboration with similar units of the Armed Forces and the State Security Forces.

Ocean Sea Company of the Royal Guard

The “Mar Océano” Company is included in the Group of Honors of the Royal Guard together with the “Monteros de Espinosa” Companies of the Army and the “Plus Ultra” Squadron of the Air Force.

Its mission and fundamental tasks are aimed at participating in the security and rendering of honors to H.M. the king and his Royal Family, as well as foreign heads of state on state visits and ambassadors presenting their credential letters to H.M. the king.

She is also the main person in charge of keeping the Diving Group of the Royal Guard operational, which she nurtures with command panels and troops with the formation of elementary divers.

The “Mar Océano” Company represents the spearhead of the Corps in the Royal Guard and in the vicinity of H.M. the king. It zealously maintains the traditions and customs of the Marine Infantry and is made up of command cadres, trained in the different units and by troops that access, either directly to the Royal Guard or through the Training Center itself or the rest of the Corps units.

Currently

With the entry into service of the strategic projection ship Juan Carlos I (L-61) and the F-100 frigates, the ability to project troops and special operations units to places far from the Spanish area of influence was increased. So much so that international commitments have meant that on several occasions, as in the case of Exercise Steadfast Jaguar-06, it is the navy that transports the most ships and personnel; therefore, in the event of a real operation, the commitments signed by Spain they force him to be able to take anywhere in the world and protect a contingent of 1800 marines and their respective equipment.

Ships under construction

| Type | Name | Allocation | Displacement tm | Slora | Speed kn. | Autonomy nm. | Endowment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submarines | |||||||

| S-80 submarines | S-81 Isaac Peral | 2023 | 3200 | 81.05 | 19.3 | 50 days | 40 |

| S-82 Narcissus Monturiol | 2024 | 3200 | 81.05 | 19.3 | 50 days | 40 | |

| S-83 Cosme García Sáez | 2026 | 3200 | 81.05 | 19.3 | 50 days | 40 | |

| S-84 Mateo García de los Reyes | 2027 | 3200 | 81.05 | 19.3 | 50 days | 40 | |

| Frigates | |||||||

| F-110 frigates | F-111 Bonifaz | ~2026 | 6100 | 145 | 25 | 150 | |

| F-112 Roger de Lauria | ~2027 | 6100 | 145 | 25 | 150 | ||

| F-113 Menéndez de Avilés | ~2028 | 6100 | 145 | 25 | 150 | ||

| F-114 Luis de Córdova | ~2029 | 6100 | 145 | 25 | 150 | ||

| F-115 Barceló | ~2030 | 6100 | 145 | 25 | 150 | ||

| Maritime Action Ships | |||||||

| BAM-Subaquatic Intervention | A-21 Poseidon | 2025 | 5000 | 85 | 15 | ? | 60 |

| Hydrographics | |||||||

| Coastal hydrographs | A- | ~2025 | |||||

| A- | ~2025 | ||||||

Projects

Air-naval capacity

The transport and use of an embarked fixed wing have been enhanced with the entry into service on September 30, 2010 of the strategic projection ship Juan Carlos I, which displaces 27,082 tons. and it has the capacity to house thirty aircraft. She is the current flagship of the Navy and mainstay of the fleet.

Decision making is underway to outline the replacement of the Navy's Harrier IIs (perhaps by the F-35B). However, official sources affirmed that the entry or not of said project was not part of its agenda. This is the Achilles heel of the naval air force, since having a capable replacement for the Harrier II is a priority.

Escorts

The 31st Squadron successfully completed its modernization process. The F-100 Álvaro de Bazán class frigates, an important project of the Armed Forces, gradually entered service. There are currently five in active service. The 41st escort squadron is made up of the six F-80 Santa María class frigates, which entered service between 1986 and 1995 and are currently halfway through their useful life, highlighting their anti-submarine capability. The Spanish Navy has a total of eleven of these ships (five F-100 and six F-80).

The Navy plans to acquire five F-110 class frigates to replace the Santa María class frigates.

Underwater weapon

The submarine fleet is currently submerged in the S-80 project, nationally manufactured submarines with independent air propulsion and high autonomy, which will make it very difficult for hostile units to detect them.

Fruit of the commitment to the S-80 and after the withdrawal of the four S-60 Delfín class units, Spain has two submarines in active service (S-71 Galerna and S-74 Tramontana) of the four S-70 Galerna class originally delivered, which will be replaced by the four S-80 series submarines currently under construction and whose delivery to the Navy is scheduled between 2021 and 2024.

Auxiliary ships

After the decommissioning of the A-11 Marqués de la Ensenada on January 31, 2012, the Navy has the combat supply ships A-14 Patiño and A-15 Cantabria. Thanks to the modernity of these ships, the Spanish Navy will have this operational facet covered for the next two decades.

The only drawback may be the monohull condition of the first one, despite the fact that the new laws regarding oil tankers do not affect military vessels, but only civilian ones.

Of the auxiliary ships, the A-101 Mar Caribe is one of the ships that performs real operations every year. Her main mission is to bring water and fuel to the Spanish rocks in North Africa.

Mine Warfare

The fight against mines is probably one of the weak points of the Spanish Navy, as the ALTAMAR Plan has not been fully developed in this field. The Navy requested six new minehunters and as many minesweepers, but only the first ones were built, six M-30 minehunters with state-of-the-art equipment, being insufficient to carry out the entrusted task. Budgetary restrictions have meant that this aspect has been neglected in order to deal with other programs.

Amphibious units

The Navy has two L-50 series amphibious assault ships: the L-51 Galicia and the L-52 Castilla, and the L-61 Juan Carlos I amphibious landing ship. of the landing ship L-41 Pizarro. The amphibious units have been completed with the twelve new LCM-1E landing craft, with the capacity to embark, transport and disembark personnel, material, vehicles or containers in amphibious operations, which have been acquired in recent years, and to which add the two prototypes of this series, with which there is a total of fourteen LCM.

Currently the Spanish Amphibious Group forms with the Italian one of NATO's joint rapid action units. Given the international context in the Mediterranean and the Middle East, they could be the first NATO units to go in case of crisis.

In addition, Spain is collaborating with the Royal Australian Navy with projects such as the LHDs (manufactured by Navantia), the LCM-1E launches and the one-year loan of the A-15 Cantabria.

Patrollers

Diverse classes of patrol boats have been causing withdrawal after the incorporation of the BAM (Maritime Action Vessels). These modular ships can carry out multiple tasks, such as rescue at sea, care for decompression syndrome, patrol and surveillance, fight against pollution and other minor ones.

Air weapon

Finally, The Navy Aircraft Flotilla intended to replace the Agusta-Bell AB 212, SH-3 Sea King and OH-6 Cayuse helicopters with a single new model (NH-90). of joint European manufacture adapted to the different functions required by the Navy (transport, evacuation, anti-submarine warfare, early warning...). The Navy was debating whether to start with the tactical transport version (NH-90 TTH) and navalize it, or convert the anti-submarine and anti-surface fighting version (NH-90 NFH) for tactical transport.

The NH-90 incorporation program included 104 helicopters for Spain distributed as follows:

- Earth Army: 48

- Air Force: 28

- Navy: 28

Of these 28, it was intended that 10 be in the TTH version to support the projection of forces and the others in a basic configuration to serve as a test platform for the different systems under development that are mounted in the other versions (Multipurpose Naval-MPN- and Airborne Surveillance & Control-ASaC-) to be incorporated in the future.

The Council of Ministers approved on May 19, 2005 the acquisition of a first phase of 45 units. However, due to the economic crisis from 2008 the program was postponed and later reduced first to 38 units in 2011 and then to only 22 devices in 2013, none of which corresponded to the Navy.

In 2018 there was talk of a second phase of the NH-90 program that could have 23 aircraft of which the Navy would have 7 that would arrive from 2023.

Given the enormous delay, the lack of helicopters (only 7 SH-3 Sea King and 7 Agusta-Bell AB 212) and their obsolescence, the Navy considered acquiring second-hand SH-60F from the United States in a quantity of at least 10 aircraft. In 2010, a request for approval of the sale of the first 6 refurbished second-hand SH-60F helicopters from the United States Navy was notified to the United States Congress.

Although at first there were no budget items for this weapons system, the Council of Ministers successively approved the financial allocation for the acquisition of three pairs of SH-60F to transform them into the variant specialized in tactical transport, for a total of 92.5 million euros. In 2018, the first two SH-60F were already available, which were temporarily included in the 10th squadron together with the SH-60B, from where they will replace the SH- 3 Sea King in the 5th squadron. The first two units of this purchase arrived at the facilities of the 5th FLOAN squadron on September 30, 2021, with 2 more expected in the first half of 2022 and the last ones at the end of that same year or beginning of 2023.

As far as fixed-wing aircraft are concerned. To replace the AV-8 Harrier II the only option on the market is the F-35B but its replacement is not clear due to budgetary reasons—the Navy budget is too little to add a proper acquisition program, and the unit cost is around 100 million euros—and political —the F-35 is not a European product, but an American one—; although since 2021, Spain has shown a growing interest in the program after the turn in the question of Germany and the search for a greater commitment with NATO after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In any case, in May 2014 the Government authorized the Spanish Navy to invest 70.3 million euros to extend the operational life of the Harrier AV-8B Plus beyond 2025, thereby ensuring that the strategic protection vessel Juan Carlos I may continue to have a fixed-wing air weapon on board, at least in the short term.

Preserved ships

Most of the few retired Spanish Navy ships that are preserved as museum ships are submarines:

- The Peral of 1888 is preserved in Cartagena (Region of Murcia).

- The two units of the Foca Class: the SA-41 in Mahón (Islas Baleares) and the SA-42 in Cartagena (Region of Murcia).

- The two units of the Shark Class: the SA-51 in Barcelona (Catalonia) and the SA-52 in Cartagena (Region of Murcia).

- The Dolphin (S-61), of the Daphne class (S-60) is moored in Torrevieja (Province of Alicante, Valencian Community). Unlike the other submarines it is not anchored in firm land but tied in the port, thus becoming the first “floating museum” of these characteristics in Spain.

- The Customs Surveillance Service patrol Albatros III is also preserved in Torrevieja.

- The Galatea, a bricbarca who was a Spanish Navy school vessel between 1922 and 1982, is preserved in Glasgow (Scotland, United Kingdom).

In 2020 it was being studied that the Tonina (S-62) could end up as a museum ship in Cartagena.

Jobs in the Spanish Navy

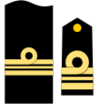

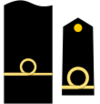

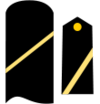

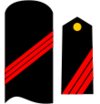

Jobs in the Spanish Navy are those in the following tables. The badges/chevrons are placed on the cuff of the uniform for walks in the officer and non-commissioned officer categories, while in the seamanship they are placed between the elbow and the shoulder, except for the use of major corporal which also goes on the cuff (see NATO Jobs and Currency).

Officers and General Officers

NCOs and seamen

| NATO Code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Spain |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Senior | Lieutenant | Brigade | Sergeant first | Sergeant | Corporal | Corporal first | Corporal | First Mariner | Marinero | |

Students and applicants

Symbols

The patron saint of the Spanish Navy is the Virgen del Carmen, considered by Catholics to be the protector and guardian of seafarers, who is called Stella Maris (Star of the Sea). Her party is celebrated on July 16 and the Navy anthem is by José María Pemán. The Salve Marinera is a song to the Virgen del Carmen.

Contenido relacionado

Buffer

The Goat's Party (novel)

Hyperinflation