Songbook (Petrarch)

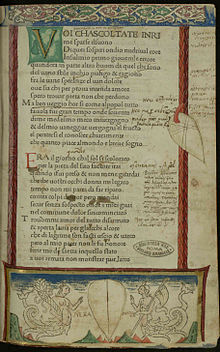

Songbook (Canzoniere in Italian) is the name by which the lyrical work is popularly known in "vulgar" Francesco Petrarca's Tuscan Rerum vulgarium fragmenta (Fragments of things in vulgar), understood vulgar as the modern conception of romance, composed in the < century span style="font-variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">XIV, and first published in Venice in 1470 by the editor Vindelino da Spira.

Features

The original title of the work Francisci Petrarchae laureati poete Rerum vulgarium frammenta. Although Petrarch encrypted his poetic glory in his verses (in Latin) and not in his rhymes (in vulgar), which he called fragmenta (fragments) and nugellae (nothings), The truth is that he carefully crafted his Cancionero for years, correcting and rewriting, adding and discarding; so that the final poetic work corresponds to a perfectly meditated and conscious purpose of the poet.

And so, in his Songbook, some particular characteristics can be noted, required by any other songbook subsequent to the one to which the adjective Petrarchan wishes to be applied:

- The work, though composed of fragments, of rime sparseIt must be unified.

- The argumental thread Songbook is the loving experience that is narrated in the first person.

- He must be dedicated to a single lady. So Petrarca in the final manuscript replaced a bullet (Donna my vene spesso ne mind), which could induce to believe the reader who had loved more of a Laura. Exceptions to this rule are the fragment CLXXI (The knot in which Love retained me) or the second quartet of CCCXVIII (When I fell from a plant, which was torn out).

- The Songbook must have a narrative sequence that leads the reader through the story of the poet's loving feeling. This results in the fact that the poems must appear to have been chronologically written in the order in which they appear in the work.

- The theme is love e non solo. The Songbook it is sprinkled with poems of friendship, political, moral, patriotic or anecdotal that, in being more easily dated, serve to accentuate the narrative progression of which has been spoken at the previous point.

- The Songbook it must be polymetric, so that the metric forms correspond to the animal state and the message that the poet wants to transmit at every moment.

Original sources

Due to the desire for neatness and improvement with which Petrarch wrote, which he used to return to the text again and again, there are several different manuscripts in which it is possible to study how Petrarch modified the text.

It is estimated that Petrarch began collecting his fragmenta in 1336-38. The first draft (called forma Correggio in honor of Azzo da Correggio, its recipient) dates from 1356-58 and, although it has not been preserved, it can be reconstructed from the material collected in the Codice degli abrozzi(Latin Vatican 3196) manuscript by the hand of Petrarch himself. A redaction immediately after this, and the first to be preserved, is the so-called Chigi form of the Vatican manuscript Chigiano L.V. 176 copied by Giovanni Boccaccio (1359-63). The definitive version of the Cancionero is found in the Latin Vatican manuscript 3195, partly idiograph (that is, copied by a copyist under the supervision of the author) and partly autograph, on which Petrarch worked until the death of him.

In addition to these three manuscripts, two others are preserved that show intermediate redactions between the Chigi form and the definitive Vatican form: the Laurenziano manuscript 41,17 which contains the so-called Malatesta form and the manuscript D II, 21 from the Querinian Library of Brescia (Querinian form).

Genesis

Petrarch, curiously, owes his literary immortality to a work written in a language in which he did not believe. Son of an exiled Florentine notary, vulgar Tuscan was only his mother tongue; Latin, on the other hand, was the usual language with which he used to write, correspond, and even make apostilles in his Songbook. For example, the beginning of the song Che debb'io far? (fragment CCLXVIII) was Amor, in pianto ogni mio riso è volto, but he replaced it with the definitive because non videtur satis triste principium (I don't see the beginning sad enough); and in other margins he writes Hoc placet pre omnibus (I like this version more than the others) or Dic aliter hic (say it differently here).

But he had the whim of composing poetry in a new language that gave him the possibility of experimenting with it and perfecting it. And he does it with the themes that were natural to the vulgar: those inherited from the Provençal lyric that through the Sicilian school had reached the Tuscan poets of the Dolce stil novo. Hence the strong influence that courtly love exerts on the Cancionero.

Language

The language of the Cancionero is characterized by vagueness and simplification.

Petrarch excludes from his vocabulary both excessive cultisms and excessively low words, so that his Cancionero is made up of only 3,275 voices. With this he manages to create a lingua franca that the writers of the Cinquecento, led by Pietro Bembo, crowned as the Italian language for poetry.

The physical imprecision with which the work is written is also notable. Petrarch only talks about the eyes, always inevitably beautiful (i begli occhi), the beautiful gesture (il bel viso) and the golden hair (i capei d& #39;gold). There are hardly any other physical references in the work. And the three adjectives that accompany Laura's three vague traits are maintained throughout the work without the passage of time (whether I have just met her, whether sixteen or seventeen years have passed) being able to alter them. Only the famous fragment But the entire description recreates the past in which the eyes were beautiful, the hair blonde and the gesture beautiful and contributes to the invariable image of Laura's appearance.

Metric

The Cancionero has a capital influence on two aspects of the meter: the rhythm of the hendecasyllable and the strophic forms.

On the one hand, it definitively makes the rhythms of the hendecasyllable a maiore with accent on the sixth syllable and a minore with accents on the fourth and octave prevail, which determines that in Spanish cultured poetry (which, starting with Boscán and Garcilaso, adopts Italian meters) these are the most common rhythms.

On the other hand, it decisively influences which stanzas will be cultivated from then on in cultured poetry. Only five forms are included in his Cancionero: sestina, ballad, madrigal, song and sonnet. He perfects and refines the madrigal that in the Cinquecento will reach its musical peak; definitively fixes the scheme of the song inherited from the Sicilian school; and, finally, he brings the sonnet to its absolute perfection, making it perhaps the most important stanza of Western European poetry. His preference for sonnets composed of quartets and non-serventesios and with triplets with the CDE CDE or CDC DCD scheme (along with the CDE DCE), determines that these are the forms with which sonnets are composed in Spain.

Structure

- This section is just a sketch and must be rewritten

The Cancionero is made up of 366 fragments (317 sonnets, 29 songs, 9 sestinas, 7 ballads and 4 madrigals) traditionally divided into two parts: the rhymes during the life of Madonna Laura and the rhymes after the death of Madonna Laura. This division, however, is due to the editors of the work and not to Petrarch himself and is suggested both by the content and by the fact that in the definitive manuscript there are several blank pages among the composition.

It opens with a sonnet as a prologue Those of you who listen to rhymes, the sleeplessness in which the poet presents his work as the fruit of his first youthful mistake and which, after asking his reader's apology, closes with the cliché of vanitas vanitatis (whatever pleases the world is a brief dream).

The following poems introduce the intensity with which the poet tests love and feeling:

To make his revenge more daunting

and charge a thousand offenses in one day,

hidden the bow Love brought

like the one who seeks in his dispossession.

It covered the virtue with great pujanza

eyes and heart of the porphy,

when there where to get another one used to

He lowered his arrow with mortal leaning.

And so troubled in the first assault,

It didn't take so much place or breath

with which I could in the narrow arm me;

or the fatty and high mountain

with cunning departing from torment,

the one I want today and can't steal from.

- (Source: wikisource)

Throughout the Cancionero, Petrarca composes the topics of love poetry that he sometimes expresses with special success. Especially famous is fragment XXXV in which he develops the cliché of the lover who, a fugitive, flees from everything and is only incapable of avoiding his own love:

Just and thoughtful the most yermos prados

I'm going to step late and slow,

and lurking with eyes to attentive

run away from those by the slain man.

Another relief I can't find in my care

to turn me away from the crowd,

because in the acts of pain I breathe

show to bring the abrasive steps;

so much that I believe since mountains, weep,

jungles and rivers know the ends

I've hidden another witness.

But I can't find such distant paths,

so harsh that we always do not go

I speak with Love and Love with me.

The love compositions of the first part abound greatly in the beauty (vague beauty) of the beloved, in which lies the spiritual elevation and transcendence of Petrarch's love. There are, for example, three songs (the so-called Three Sisters) dedicated exclusively to the praise of Laura's (beautiful) eyes. Read, for example, fragment LXXII (Gentle lady, I see).

With regard to the idealized descriptions of Laura, fragment XC admirably includes a large part of the topics that include the usual glorification of the beloved:

It was the hair to the untied aura.

that in a thousand knots of gold interwoven;

and in the gaze without measure arbit

That beautiful brightness, now off;

the gesture, of gentle favor painted,

be honest or false, I believed it;

since loving plaster in me hid,

Who's afraid of seeing me like this?

It wasn't his rude mortal thing,

but an angel's work; and it sounded

His voice doesn't sound like a human voice:

a celestial breath, a sun looked

when I saw it; and if it were not now,

not because it loosens the bow healthy damage.

- (Source: wikisource)

And the triplets of fragment CLVII break down the Petrarchan canon of feminine beauty in their six verses:

The fiery gesture snow, they raise it gold,

the ebony eyebrows, and the sole eyes,

for those who have not erred the arch Love;

pearls and roses in which the evil I love

formed a burning voice among snare;

crystal your crying, call your sigh.

- (Source: wikisource)

In the second part of the work, faced with the desolation of his death, Petrarch works on Laura a process of beatrization that in dreams or in the imagination consoles him and promises eternal union in the darling. Thus in the CCCII rhyme:

He raised my thought to where it was.

the one I seek and find no more in the land,

and there among the third heavens

I saw her more beautiful and less tall.

He took my hand and said, "In this sphere

You will be with me, if the soul does not err:

I'm the one who gave you so much war

and the day ended before the sun fell.

My good does not fit in human thought:

I'm just waiting for you, and what you loved crazy,

that a beautiful veil was, remained on the ground."

What's the matter?

That, to the echo of his accent, he missed little

to stay there in heaven.

- (Source: wikisource)

The Cancionero closes with absolute regret for having loved:

Weeping I go the times already past

I wasted in loving things on the ground,

instead of getting up in flight.

without giving me such faint examples.

You, that my evils have grieved,

invisible and immortal, Lord of heaven,

Your help lends to the soul and Your comfort,

and heal with Your Grace my sins;

So, if I lived in storm and war,

die in shame and peace; if he walketh evil,

Well, at least leave the land.

The little that I've got in life

and to die with Your hand clings;

You know that in You I find only hope.

- (Source: wikisource)

The Petrarchan songbooks

A collection of lyric poems created in the manner of the Petrarchan Songbook is known as a Petrarchist Songbook, that is, a collection of very personal poems with a core line of love. The meaning with which the adjective Petrarchist enriches the term cancionero is important, because in Spanish poetry this same term has also been used to describe, at least, two other types of sets of poems. In the first, in song poetry, with the meaning of an anthology that generally collects poems by very various authors and very various topics. Such is the case of the Cancionero de Baena, the Cancionero de Stúñiga or the Cancionero General. In the second, with the meaning of a collection of poems by a single author, as is the case of the Cancionero de Pedro Manuel de Urrea or Jorge de Montemayor.

Fortune in Spain

Although the Cancionero had a very powerful influence on European lyric poetry, in Spain no songbooks have been written that could be classified as Petrarchan, with the exception perhaps of the Verses of Fernando de Herrera i>. However, much of the Spanish love poetry written during the 16th and 17th centuries is Petrarchan poetry.

Garcilaso de la Vega, whose premature death did not allow him to articulate a work of this nature, is a poet strongly influenced by the poetry of Petrarch. In general, all of his verses exude Petrarchism to the point that some are more or less literal translations of verses from his model; especially the sonnet Thinking that the path went straight, whose second quartet and first tercet very faithfully follow the fragment CCXXVI (Loneliest Sparrow on No Roof)

Lope de Vega is also a poet to whom Petrarch left a deep mark. The Rhymes of Him (1602), although it lacks many of the characteristics that would allow it to be defined as a Petrarchan Songbook, is a loving poetic work with a strong influence of the Italian poet. Sonnet IV (It was the joyous eve of the day), for example, is inevitably reminiscent of fragment III (It was the day that the sun turned pale) in which Petrarch declares how he met Laura on Good Friday. Also Petrarchan, in their own way, are the delicious Human and Divine Rhymes of Mr. Tomé de Burguillos that develop parodies of the most common topics of Petrarchanism.

The Petrarchan influence of Francisco de Quevedo is usually highlighted in his Sing alone to Lisi (and the rest of his love poetry). Curiously, Quevedo covered the aforementioned fragment CCXXVI in the sonnet Loneliest bird on which roof...

Contenido relacionado

Alvaro del Amo

Rodolphe Topffer

Alejandro Jodorowsky

Miquel Barcelo Garcia

Roberto Fontanarrosa