Song of the Nibelungs

The Song of the Nibelungs (German: Nibelungenlied) is a epic song of Germanic origin, written around the 13th century, in the Middle Ages.

This work brings together many of the existing legends about the Germanic peoples, mixed with historical facts and mythological beliefs and, due to the depth of its content, complexity and variety of characters, it became the German national epic, with the same hierarchy literature of the Cantar de mío Cid in Spain and the Cantar de Roldán in France. The manuscript of the Song, which is kept in the Bavarian State Library, was inscribed in UNESCO's Memory of the World Program in 2009 in recognition of its historical significance.

The German composer Richard Wagner drew some inspiration from this epic poem and from the Germanic and Norse mythological tradition to compose the operatic tetralogy Der Ring des Nibelungen ('The Ring of the Nibelungen& #39;). It was also made into a film by Fritz Lang in 1924 under the title The Nibelungs.

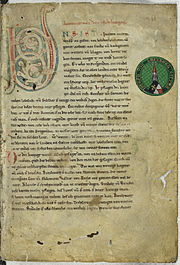

Manuscript versions

In addition to Nibelungenlied (Song of the Nibelungs') it is known in Middle High German, the language in which it is written, as Nibelunge not by the words that appear in the last verse of the manuscript found in Hohenems (Austria) "daz ist der Nibelunge not", which would mean This is the destruction of the Nibelungs. The poem in its various written forms was lost at the end of the s. XVI, but manuscripts as old as the s. XIII would be rediscovered in the XVIII. There are about 37 texts in German, mostly fragmentary, and a reworking in Dutch, which only contains the lamentation and an index. The text contains approximately 2,400 stanzas divided into 39 songs. The title by which the poem has been known since its discovery is derived from the final line of one of the three main versions, "hie hât daz mære ein ende: daz ist der Nibelunge liet" ('here the story comes to an end: this is the song of the Nibelungs'). The manuscripts were found mostly in the southern part of the Germanic area (Switzerland, Voralberg, Tyrol). The three oldest complete manuscripts were named with letters in the 19th century by the philologist Karl Lachmann in his work Der Nibelunge Noth und die Klage nach der ältesten Überlieferung mit Bezeichnung des Unechten und mit den Abweichungen der gemeinen Lesart (Berlin: Reimer, 1826):

- A = Manuscript Hohenems-Münchener (last quarter of the century)XIII) at the Bavarian State Library (Cgm 34)

- B = Codex Sangallensis 857 (middle centuryXIII o antes), en la Biblioteca de la Abadía de San Gall (Cod. Sang. 857)

- C = Hohenems-Laßbergische / Donaueschinger Handschrift (second quarter of the century)XIII), since 2001 at the Badischen Landesbibliothek Karlsruhe (Cod. Donaueschingen 63)

The genealogical classification of the texts responds to the last verse of the text. Thus, manuscripts A and B end with "daz ist der Nibelunge not" and manuscript C ends with "daz ist der Nibelunge liet". Text C is a revision for the public, the tragic elements of which have been softened, and for this reason it enjoyed more popularity, although from a modern perspective, manuscript B is more accomplished. There are several manuscripts that resemble manuscript C, collectively known as *C. There are fewer who follow the same pattern as B; these are known as *B. Manuscript A appears very close to B for the most part, but is not so neatly written and therefore belongs to group *B.

Authorship and dating

The Nibelungenlied, like other Middle High German heroic epics, is anonymous. This anonymity extends to literary discussions of other Middle High German works: although it is common practice to judge or praise the poems by others, no other poet refers to the author of the Nibelungenlied. Strassburg attributes a lost epic, they have not been widely accepted. However, the poem is believed to have had a single author, possibly working in a "Nibelungen workshop" ("Nibelungenwerkstatt") along with the author of the Nibelungenklage. The latter work identifies a "meister Konrad" as the author of an original Latin version of the Nibelungenlied, but it is generally taken for fiction. Although the existence of a single Nibelungen poet, the The text's degree of variation and its background in an amorphous oral tradition mean that ideas of authorial intent should be applied with caution. It is also possible that several poets were involved, perhaps under a single "leader" 3. 4; who could be considered the "poet of the Nibelung".

The Nibelungenlied is conventionally dated to around the year 1200: Wolfram von Eschenbach refers to the cook Rumolt, often considered an invention of the Nibelungenlied poet, in his Nibelungenlied i>Parzival (c. 1204/5), which gives a date on which the epic must have been composed. Furthermore, the poem's rhyming technique is more closely resembling that used between 1190 and 1205. Attempts to show that the poem alludes to various historical events have generally been unconvincing.

Current theory of the poem's creation emphasizes the poet's concentration on the Passau region: the poem highlights the relatively unimportant figure of Bishop Peregrino of Passau, and the poet's geographical knowledge seems much firmer for this area than for other places. These facts, combined with the dating, have led scholars to believe that Wolfger von Erla, Bishop of Passau (reigned 1191–1204) was the poem's patron. Wolfger is known to have patronized other literary figures, such as Walther von der Vogelweide and Thomasin von Zirclaere. The attention paid to Bishop Peregrino, who represents the actual historical figure of Bishop Peregrino of Passau, would thus be an indirect homage to Wolfger. Furthermore, Wolfger was attempting to establish Pilgrim's sainthood at the time of the poem's composition, which provides an additional reason for his prominence.

There is some debate as to whether the poem is an entirely new creation or if there was an earlier version. Jan-Dirk Müller is of the opinion that the poem in its written form is entirely new, although he admits the possibility that an orally transmitted epic with relatively consistent content could have preceded it. Elisabeth Lienert, for her part, postulates an earlier version of the text, from around 1150, because the Nibelungenlied uses a stanza form current at the time (see #Form and style).

Whoever the poet is, he seems to have had some knowledge of German Minnesang and chivalrous romance. The poem's concentration on love (minne) and the portrayal of Siegfried as a loving service to Krimhild is in keeping with the courtly romances of the time, with the Aeneasroman of Heinrich von Veldeke perhaps providing concrete models. Another possible influence is the work of Hartmann von Aue Iwein, as well as Erec. These courtly elements are described by Jan-Dirk Müller as a kind of facade, under which the old heroic ethos of the poem remains. Furthermore, the poet seems to have known Latin literature. The role given to Krimhilda in the second (originally first) stanza is suggestive of Helen of Troy, and the poem seems to have borrowed a number of elements from Vergil's Aeneid. Old French chanson de geste.

Structure

The poem is made up of 39 songs or adventures, divided into two large nuclei: the first part, Siegfried's poem, includes songs I to XIX, and the second part, Krimilda's revenge, includes songs XX to XXXIX.

Part One

Cantos I to V. In these cantos the characters are introduced, Siegfried's first adventures with the Burgundians take place, and he finally asks for Krimilda's hand.

Cantos VI to XIV. In these songs the knot of the plot occurs: in order to marry Krimilda, Siegfried is asked to help Gunther to marry Brunhilda, Queen of Iceland. To do this they cheat, since the Icelandic queen required a combat test, and only Siegfried was capable of performing it. Realizing that she is marrying a lesser warrior, on their wedding night and subsequent Brunhild refuses to consummate the marriage: she again helps Siegfried Gunther, and as proof takes Brunhild's belt, which she gives to Krymilda. Siegfried and Krimilda return to Niderland, and years later they are invited to Worms. There the key event takes place, which is the dispute between the two queens over which king (Gunther or Siegfried) was superior to the other; Krimilda shows the belt and Brunilda seeks revenge.

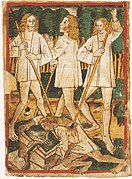

Cantos XV to XIX. In these songs the betrayal takes place, carried out by Gunther and Hagen; the latter deceives Krimilda to find out the weak point of Siegfried, who dies in a hunting party. The treasure of the Nibelungs is taken to Worms and buried in the Rhine.

Part Two

Cantos XX to XXII. This section begins 13 years later than the previous one and moves the events to another setting, the kingdom of the Huns, where Attila is left a widower and is suggested to marry Krimilda. He sends messengers, led by Rudigero of Bechlaren, who makes the proposal. Despite Hagen's distrust, who thought that placing her largest army at the disposal of the betrayed queen would bring misfortune, Krimilda's brothers convince her to marry the king of the Huns. The next two songs narrate the queen's journey to the country of the Huns.

Cantos XXIII to XXXIX. In these songs, Krimilda invites her brothers to Huneland, an invitation that they accept and travel to those lands. Although in the first part the Burgundians were differentiated from the Nibelungs, in this one the names are synonymized. Gunther and Hagen leave accompanied by a thousand warriors and after a long journey they arrive at Attila's castle. Shortly after his arrival, skirmishes began, at first with little intensity, but later they became general. The least important knights die first and then the most valuable. Hagen murders the son of Krimilda and Attila. In the end Gunter and Hagen are defeated and put under pressure. Krimilda demands Hagen to tell them where Siegfried's treasure is and after the prisoner's refusal, she kills him. King Attila recognizes the value of his enemy Hagen for which he reproaches Krimilda for his death; His sorrow is shared by the knight Hildebrand, who decides to avenge Hagen and murders Krimilda. With this bloody denouement concludes the "Song of the Nibelungs".

Editions

- Karl Bartsch, Der Nibelunge Nôt: mit den Abweichungen von der Nibelunge Liet, den Lesarten sämmtlicher Handschriften und einem Wörterbuche, Leipzig: F.A. Brockhaus, 1870–1880

- Alice Horton, Translator. The Lay of the Nibelungs: Metrically Translated from the Old German Text, G. Bell and Sons, London, 1898. Line by line translation of the "B manuscript". (Deemed the most accurate of the "older translations" in Encyclopedia of literary translation into English: M-Z, Volume 2, edited by Olive Classe, 2000, Taylor & Francis, pp. 999-1000.)

- Margaret Armour, Translator. Franz Schoenberner, Introduction. Edy Legrand, Illustrator. The Nibelungenlied, Heritage Press, New York, 1961

- Michael S. Batts. Das Nibelungenlied, critical edition, Tübingen: M. Niemeyer 1971. ISBN 3-484-10149-0

- Laura Mancinelli, The canzone dei Nibelunghi. Problemi e valori, Torino: Giappichelli 1969

- Laura Mancinelli, Memoria e invenzione: Introduzione alla letteratura del Nibelungenlied, Torino: Einaudi 1972

- Laura Mancinelli, I Nibelunghi, Torino: Einaudi 1972. ISBN 978-88-06-23661-8

- Boor's Helmut. Das Nibelungenlied, 22nd revised and expanded edition, ed. Roswitha Wisniewski, Wiesbaden 1988, ISBN 3-7653-0373-9 This edition is based ultimately on that of Bartsch.

- Robert Lichtenstein. The Nibelungenlied, Translated and introduced by Robert Lichtenstein. (Studies in German Language and Literature Number: 9). Edwin Mellen Press, 1992. ISBN 0-7734-9470-7 ISBN 978-0-7734-9470-1

- Hermann Reichert, Das Nibelungenlied, Berlin: from Gruyter 2005. VII, ISBN 3-11-018423-0 Edition of manuscript B, normalized text; introduction in German.

- Hermann Reichert, Nibelungenlied-Lehrwerk. Sprachlicher Kommentar, mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik, Wörterbuch. Passend zum Text der St. Galler Fassung (“B“). Wien: Praesens Verlag 2007. ISBN 978-3-7069-0445-2 Linguistic help for beginners (in German).

- Ursula Schulze, Das Nibelungenlied, based on manuscript C, Düsseldorf / Zürich: Artemis & Winkler 2005. ISBN 3-538-06990-5

- Burton Raffel, Das Nibelungenlied, new translation. Foreword by Michael Dirda. Introduction by Edward R. Haymes. Yale University Press 2006. ISBN 978-0-300-11320-4 ISBN 0-300-11320-X

- A.T. Hatto, The NibelungenliedPenguin Classics 1964. English translation and extensive critical commentary with appendices.

- Los Nibelungos, Version of José Miguel Mínguez Sender, Editorial Alliance - Literature 5729, Madrid - Spain, 2009 ISBN 978-84-206-4988-7

- The Song of the Nibelungs, metric translation, introduction and notes by Jesús García Rodríguez, Editorial Akal, Collection Via Láctea, Madrid, 2018, 464 p. ISBN: 978-84-460-4489-5. Full translation of the original text, with an introductory study and numerous illustrations.

Contenido relacionado

Deuteronomic tradition

Gonorrhea

Cretan maze