Slovak language

The Slovak (slovenčina, ![]() slovenský jazyk (?·i)) is a Slavic language of the Western group spoken mainly in the Republic of Slovakia, where it is the official language. Since 2004, it has been one of the 24 official languages of the European Union. It is also a co-official language of Voivodina, an autonomous province of northern Serbia. There are also Slovak-speaking minorities in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Ukraine (such as Czechoslovakia, 1918-1938), Austria, Poland and Romania. Outside Europe, there are immigrant communities that have preserved the use of their language, especially in the United States, Canada and Australia.

slovenský jazyk (?·i)) is a Slavic language of the Western group spoken mainly in the Republic of Slovakia, where it is the official language. Since 2004, it has been one of the 24 official languages of the European Union. It is also a co-official language of Voivodina, an autonomous province of northern Serbia. There are also Slovak-speaking minorities in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Ukraine (such as Czechoslovakia, 1918-1938), Austria, Poland and Romania. Outside Europe, there are immigrant communities that have preserved the use of their language, especially in the United States, Canada and Australia.

It is estimated to be spoken by about 5.2 million people (2015), of which about 4.34 million in Slovakia (2012).

Its closest linguistic relative is Czech, with which it is mutually intelligible. Most adult Slovaks and Czechs are able to understand each other without difficulty, having been in constant contact with both languages via radio and Czechoslovakia television until the dissolution of the country in 1993. The youngest may have difficulty understanding certain words that are very different in both languages or when the interlocutor speaks too fast. However, it is still possible to use Slovak in official communication with the Czech authorities. Czech-language books and films are widely distributed in Slovakia. A more limited intercomprehension with Polish is also possible.

Slovak should not be confused with Slovene (slovenščina), as although it is another language in the Slavic group, they are two different languages: Slovene is part of the West South Slavic group (like the Croatian language), while Slovak is part of West Slavonic, like Czech or Polish.

Like most Slavic languages, Slovak is declined (six cases), has three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter) and its verbs have perfective or imperfective aspect. It is a fusion language with a complex morphological system (characterized by a rich system of derivative prefixes and suffixes, as well as diminutives) and relatively flexible word order. His vocabulary is heavily influenced by Latin, German, Hungarian and other Slavic languages. Regarding pronunciation, Slovak words are always stressed on the first syllable and there are long and short vowels; a peculiarity of Slovak is that r and l can act as vowels, resulting in seemingly vowelless words such as prst ("finger").

The different dialects of Slovak can be classified into three large groups: Western (closest to Czech, especially the Moravian varieties), Central and East (which has features in common with Polish and East Slavic languages and is the furthest from the standard language). Not all dialects are fully mutually intelligible, so a speaker of western Slovakia may have difficulty understanding an eastern dialect and vice versa.

Until the 18th century, the literary language in Slovakia was Czech. Modern literary Slovak was codified on the basis of the central dialect in the mid-19th century, largely thanks to the linguist Ľudovít Štúr. Slovak uses a Latin alphabet of 46 graphemes similar to Czech, with digraphs and numerous diacritics.

Historical, social and cultural aspects

Slovak shares a common origin with Moravian and Czech. The three languages constitute one of the three subgroups of the West Slavic group, Czecho-Slovak. (The other two are the Lehitic subgroup and the Sorbian subgroup). Conventionally, colloquial varieties of Slovak are grouped into three divisions:

- Western Slovak, geographically close to the Moor.

- Central Slovak

- Eastern Slovak

History

The history of the Slovak language is traditionally divided into two main eras, which in turn are divided into several periods:

- Preliterary period (predspisovné obdobie), from the 9th to the end of the 18th century:

- Early preliterary period (froe predspisovné obdobiecenturies IX to X;

- Old preliterary period (staršie predspisovné obdobieXI to 15th centuries;

- recent preliterary period (mladšie predspisovné obdobie16th to 18th centuries;

- literary era (spisovné obdobiefrom the end of the centuryXVIII to date:

- Bernolák period (1787-1844);

- Štur period (from 1844 to 1852);

- Period of Reform (obdobie reformnéfrom 1852 to 1863;

- Matica Slovenská (from 1863 to 1875);

- Martin Period (1875-1918);

- period between wars (1919-1940);

- modern period (since 1940).

Pre-literary times

9th to 10th centuries

The history of the Slovak language begins in the 9th century, when the Proto-Slavic dialects spoken in the northern part of the Pannonian plain begin to differentiate, especially in the principality of Nitra, which is the first known Slovak state, and later in Great Moravia. In 863 Cyril and Methodius came to Great Moravia and Old Slavonic became the liturgical language. It was usually written in the Glagolitic alphabet, later also in the Cyrillic alphabet (rarely in the Latin alphabet). Among the documents found from this time, one of the most important is the Kiev missal, a prayer book dating from the Xcentury span> and which is perhaps the oldest known document written in a Slavic language. Although it is written in Old Slavic, a South Slavic language, the language used contains characteristic elements of West Slavic languages.

11th to 15th centuries

This period of the development of Slovak is characterized mainly by the evolution of the spoken language and the use of Latin in the territory of present-day Slovakia. Latin was the language used by the Kingdom of Hungary in education, religion and administration. Documents from the time written in Latin contain many Slovak words, place names and even loanwords. The record of Zobor (1113) refers to Boencza (Bojnice) and the waters of Vvac (Váh). This period is also characterized by the gradual appearance of Czech in Slovakia from the 14th century.

16th to 18th centuries

The arrival of humanism and the Renaissance in Slovakia was accompanied by the first printed texts in Slovak, such as the Esztergom rite (Ostrihomský ritual) in 1625. While Latin was losing ground, Czech became the language of Protestantism in 1610. However, Slovaks use Slovakized Czech: ě, au , and ř are often replaced by e, ú and r, and some forms are borrowed from Slovak.

Speaks called "educated Slovak" (kultúrna slovenčina), which is not yet standardized and does not have a uniform structure and spelling. Three forms are distinguished: western, central and eastern, each with its own variants and different regional influences. One of the earliest known texts in High East Slovak is a threatening letter addressed to the city of Bardejov dated around 1493 which contains elements of Ukrainian origin and begins like this: "Vy zly a nespravedlivy lvde bardiowcy vi ste naszych bratow daly zveszaty lvdy dobrich a nevinnich iako modere necnotlyvy ktory any vam ani zadnomv nicz nebili vinni" ("You evil and unjust people of Bardejov, have hanged our brothers, good and innocent men, as callous murderers, [people] who have done nothing to you or to anyone").

At this time the first descriptions of Slovak appear. In Grammatica Slavico-Bohemica (1746), Pavel Doležal compares standard Biblical Czech with Slovakized Czech. A 1763 Latin-Slovak dictionary, Syllabus Dictionarii Latino-Slavonicus, probably largely written by Romuald Hadbávny, a monk of the Camaldolese Order of Červený Kláštor, also contains a short introduction to spelling and spelling. grammar of the language. The Camaldolese Bible (Swaté Biblia Slowénské aneb Pisma Swatého, 1756 and 1759) is the first known complete Slovak translation of the Bible.

Literary age

The year 1787 marked a turning point in the history of Slovak: that year saw one of the most important attempts to normalize Literary Slovak or Standard Slovak (spisovná slovenčina).

Bernolák's period (from 1787 to 1844)

The first major attempt to standardize Slovak was made by the Catholic priest Anton Bernolák, who published in 1787 the Dissertatio philologico-critica de literis Slavorum and its appendix Orthographia. He went on to describe his language in Grammatica Slavica (1790) and Etymologia vocum Slavicarum (1790). Bernolák's language, commonly called bernolákovčina, is based on Western Learned Slovak, particularly Trnava speech, albeit with elements of Central Slovak (especially the ľ sound). The new standard is not unanimously accepted: one of the main critics is the writer Jozef Ignác Bajza, who defends his own version of literary Slovak against Bernolák's followers and considers himself the first to have standardized Slovak. However, the new standard Slovak is used in some schools and literary works appear in bernolákovčina: one of the most active writers is Juraj Fándly. Bernolák continued to work on his language, and after his death his five-volume Slovak-Czech-Latin-German-Hungarian dictionary was published (S lowár Slowenskí, Česko-Laťinsko-Ňemecko-Uherskí , 1825-1827).

The Bernolák language is characterized by, among others, the following features, which differ from modern Slovak:

- they don't exist. and and ♪, always written i or I;

- instead of j, g and v, we found respectively g, ğ and w;

- all the nouns begin with capital, as in German;

- There are no diptongos;

- There is no rhythmic rule;

- There is a vocation;

- There are some differences in declines and vocabulary.

Period of Štúr (from 1844 to 1852)

The second attempt at standardization is the work of Ľudovít Štúr and is approved at a meeting of the Tatrín cultural society in Liptovský Mikuláš, in August 1844. In 1846, Štúr published the works Nauka reči slovenskej ("Learning the Slovak language") and Nárečja slovenskuo alebo potreba písaňja v tomto nárečí ("The Slovak dialect or the need to write in this dialect"), in which he advocates a literary language uniting the Slovaks and describes the form he would like to give that language, based on Central Slovak. Among the features that differentiate it from Bernolák's proposal and from neighboring languages, we can mention the presence of diphthongs (ja, je, uo), the absence of the ľ, the rhythmic rule and an orthography closer to the current language (g, j and v represent the same sounds as today and the initial of common nouns is not capitalized).

Like the bernolákovčina, the štúrovčina is not without controversy. Michal Miloslav Hodža, for example, criticizes the Štúr spelling as being too isolated from the other Slavic languages. Ján Kollár's criticisms are harsher: he was opposed to the introduction of a literary Slovak and preferred a Slovakized version of Czech. Convinced of the need for the unity of all Slavs, he considered that the language of Štúr was detrimental to this unity and spoke out against it together with other Czech and Slovak writers in Hlasowé o potřebě jednoty spisowného jazyka pro Čechy, Morawany a Slowáky ("Voices on the need for the unity of a literary language for Czechs, Moravians and Slovaks", 1846).

Reformation Period (1852 to 1863)

The reform of the Štúr language was decided on the initiative of Martin Hattala at a meeting held in Bratislava in October 1851, at which Štúr himself and his followers Hodža and Hurban, among others, were present. The new spelling was described by Hattala the following year in Krátka mluvnica slovenská.

The reform mainly affected spelling and morphology, some of its main aspects being the following:

- the introduction and e ♪ according to etymological criteria;

- the diptongos Ha!, Heh. and uo are written, respectively, ia, ie and ô;

- the sounds are introduced ä and α;

- ., ., ň, α written d, t, n, l in front of e, i and I;

- the past of the verbs is formed with -l instead of with - Wow. or -v;

- the termination of the singular neutral nominative of adjectives is - Yeah. instead of - Wow.;

- Neutral nouns completed in - Yeah. they go on to finish -Oh..

The main goal of the reform is to bring the spelling and some forms closer to the other Slavic languages, especially Czech. This version of literary Slovak is roughly the one still in use today.

Period of the Matica slovenská (from 1863 to 1875)

This rather short period is delimited by the founding of the Matica slovenská, in 1873, until its closure in 1875, imposed by the Hungarian authorities. The Matica slovenská ("Slovak Foundation") was a scientific and cultural institution based in Martin. It had a linguistic section headed by Martin Hattala, whose aim was to develop the literary standard of the Slovak language. During that period several corrections were made. For example, some forms were replaced by more modern ones: ruce and noze, the datives and locatives of "mano" and "pie", respectively, were replaced by the more regular forms ruke and nohe. Hattala published Mluvnica jazyka slovenského ("Grammar of the Slovak Language") in 1864 to spread the literary norm, and the priest Jozef Karol Viktorin published that same year Grammatik der slowakischen Sprache, aimed at foreign audiences.

Martin period (1875 to 1918)

After the disappearance of the first Matica slovenská, the town of Turčiansky Svätý Martin (today simply Martin) became the center of many institutions and societies whose aim was the improvement of literary Slovak. Several Slovak-language newspapers were published here, such as Orol, Národní hlásnik, Živena, etc. The most characteristic feature of this period is the "use of Martin" (martinský úzus), a form of literary Slovak influenced by the language of the inhabitants of Martin and its environs, but with some hesitancy regarding the use of the ä, the ľ and the rhythmic rule.

Linguist Samuel Czambel published Rukoväť spisovnej reči slovenskej ("Handbook of the Slovak Literary Language") in 1902 in order to consolidate the literary language. In it, he lays down precise rules in respects where Martin's usage wavered (for example, the ä can only be used after a labial consonant) and removes some archaisms codified by Hattala. Czambel's norm subsequently had several corrections, notably by Jozef Škultéty, who wrote the second and third editions of Rukoväť spisovnej reči slovenskej in 1915 and 1919.

At that time, the Slovaks lived in the Kingdom of Hungary, ruled by the Hungarian nobility, who tried to assimilate non-Hungarians. However, this did not prevent the development of the Slovak language and culture. Writers such as Svetozár Hurban-Vajanský and Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav contributed to the development of the language in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Interwar period (1919 to 1940)

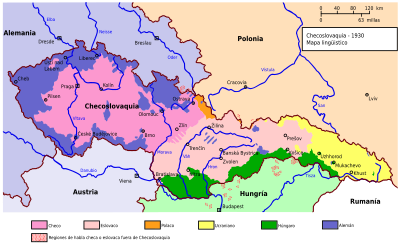

In 1918 the First Czechoslovak Republic was proclaimed. The Slovaks were self-governing for the first time in a thousand years, but the 1920 constitution stipulated that the official language was the 'Czechoslovak language', of which Czech and Slovak were variants. It had been used for a long time, for example, in literature, it came to be used in all kinds of schools, in science and in administration. Direct contact with the Czech intensified, which had a strong influence on the Slovak. In Slovak texts (especially administrative ones) from the 1920s, many Czech-influenced words and phrases are present, as users of literary Slovak were not always aware of the differences between the two languages.

The first Slovak radio started broadcasting in 1926, which helped reinforce the oral form of the language and consolidate its pronunciation. In 1931, the Matica slovenská published Pravidlá slovenského pravopisu ("Rules of Slovak Spelling") which, despite its title, deals not only with the spelling, but also helps to consolidate certain aspects of phonology (such as vowel length) and orthography (such as the spelling of the prefixes s-, z-, vz-). This book also served as the basis for the development of Slovak textbooks for a decade. However, this work adopts the theory of the existence of a "Czechoslovak language" and includes in the Slovak vocabulary Czech words such as mluviť ("speak"), rejects Slovak terms in use (for example, kefa, " brush") alleging that they are Germanisms or Magyarisms, admits two variants for certain words, one of them being the Czech (svoboda, Czech form, together with the Slovak sloboda, "freedom"), etc. The publication of Pravidlá slovenského pravopisu sparked outrage from the Slovak public. One of the reactions to this work was the publication from 1932 in Košice of Slovenská reč ("Slovak language"), a "monthly magazine for the interests of the literary language", which Matica slovenská took over the following year at Martin. The aim of this magazine was to differentiate Slovak from Czech and to oppose the idea that Czech was the national language of Czechoslovakia.

The 1930s were a watershed period for Slovak, confirming its stability and viability and developing its vocabulary for use in science and other disciplines.

Modern period (since 1940)

In 1939, a few months after the Munich Agreement, Czechoslovakia broke up and the Slovak Republic was formed, which would cease to exist in 1945. Despite the difficulties caused by the war, education and culture continued to develop and the vocabulary specific to certain fields increased. For the first time in its history, Slovak was not under pressure from another language. Starting in 1943, the linguistic study of Slovak was carried out in the new Institute of Linguistics of the Slovak Academy of Sciences and Arts. New editions of Pravidlá slovenského pravopisu were published in 1940 and 1953. The removal of some irregularities in 1968 marked the last reform of the Slovak spelling.

The issue of equal treatment between the Czech and Slovak nations, exemplified by the "hyphen war," contributed to the dissolution of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic and the creation of the present Slovak Republic in 1993. The influence of Czech diminishes. With the fall of communism, Russian is abandoned; many Slovaks went on to adopt English and loanwords from this language are multiplying. Finally, in 2004, Slovakia joined the European Union and Slovak became one of its official languages.

Phonetic evolution

Slovak, like the other Slavic languages, descends from Proto-Slavic, a hypothetical language spoken between the 6th and 9th centuries. Since then many variations have been produced; some are shared by all Slavic languages, and others are specific to a small group of languages or only one of them.

In Proto-Slavic, syllables could not end with a consonant, and consonant clusters at the beginning of a syllable were rare. There were two vowels called yers, usually spelled ь and ъ (sometimes transcribed as ĭ and ŭ), and could be "strong" or "weak" (Havlík's law): yers were strong before a weak yer, and weak at the end of a word or before a strong yer or another vowel. In all Slavic languages, most of the weak yers have disappeared (the ь sometimes leaves a trace in the form of a palatalization of the preceding consonant), which has given led to the appearance of numerous clusters of consonants, characteristic of modern Slavic languages. Strong yers, on the other hand, have been transformed into various vowels, depending on the language. In Slovak, ъ has become o (sometimes e, a or á), and ь has become e (sometimes o, a or á ):

- ♪Last → ("I dream");

- ♪dьnь → deň ("day");

- ♪dъždь → dáž ("luvia").

This evolution explains the phenomenon of mobile vowels, that is, vowels that disappear when certain words are declined: *pьsъ ("dog") evolved to pes, but its genitive *pьsa is psa. Slovak, however, regularized some words: the genitive of domček (← *domъčьkъ, "little house") should be *domečka (← *domъčьka), but is actually domčeka, formed regularly from the nominative.

Proto-Slavic also had two nasal vowels, ę and ǫ, which have now been lost in all Slavic languages except Polish and Kashubian. In Slovak, ę has become a (ä after a labial consonant) and ia when it was long; ǫ has become u or ú depending on its length:

- ♪r →ka → ruka ("mano", compare with the Polish ręka);

- ♪męso → mäso ("carne", share with the Polish mięso).

The jat', a vowel often transcribed as ě, in Slovak has become ie and sometimes shortened to e:

- ♪světъ → svet ("world");

- ♪rěka → rieka ("rio").

The sounds i and y have been confused in Slovak (although an older i usually palatalizes the preceding consonant). The spelling retains this distinction, but i and y are pronounced identically in modern Slovak.

Groups of type CorC, ColC, CerC and CelC (where C represents any consonant) have undergone various modifications in all Slavic languages. In Slovak, they have undergone metathesis to become CraC, ClaC, CreC and CleC respectively:

- ♪golva → hlava ("head") in Polish głowain Russian Golová),

- ♪dorgъ(jь) → drahý ("caro", Polish drogiRussian dorogój),

- ♪berza → breza ("abedul" in Polish brzozain Russian berëza).

Groups of type CRьC and CRъC (where R stands for r or l) are, in turn, the origin of the syllabic consonants in Slovak:

- ♪slьza → slza ("lagrima")

- ♪krúvь → krv ("blood").

The intervocalic j usually disappears to give rise to a long vowel: stáť ("to stand up"), dobrá ("good") and poznáš ("[you] know") have, for example, the Russian equivalents stojátʹ, dóbraja and znáješ. However, the j has been maintained in words such as possessive pronouns (moja, moje); Czech has gone further by allowing má and mé.

As far as consonants are concerned, the Slavic languages have undergone two palatalizations:

- La first palatalization transformed the k, the g and the ch in č, ž and š before e, i, ь and j, which explains some alternations in conjugation and derivation: sluha ("sirviente", the h from a g) / služiḳ ("serve"), plakaḳ ("screw") / plače ("[he] cries").

- La second palatalization transformed the same consonants before ě and some i in ć, ź and ś (palatal snacks), which later became c, z and s: vojak ("soldated") / vojaci ("welded"). The Slovak, however, has regularized the effects of this palatalization on the decline: na ruce ("in the hand", still correct in Czech) became na ruke, form closer to the nomination Ruka.

Among the evolution that consonants have undergone, a characteristic feature of Slovak (and which it shares with Czech, Upper Sorbian and Ukrainian) is the systematic transformation of g into h (for example, noha "pie" becomes noga in Polish, Russian, or Slovene). zg group, appearing in rare words like miazga ("lymph"). Today, g is found almost exclusively in words of foreign origin.

Evolution of Grammar

Although many features of Proto-Slavic grammar have been preserved in modern Slovak, some transformations have also occurred:

- The dual has disappeared completely. There are only some remains, such as the irregular plurals of oko ("ey") and A lot. ("hear"), respectively oči and uši.

- The vocation has disappeared (only it remains in fixed expressions).

- In the protoeslavo, the termination of the nouns determined their belonging to a certain pattern of decline. Today, the gender of the word has become a more important factor. Today, some patterns of decline have disappeared or are only found in some irregular words.

- Adjectives had a long form and a short form, which was used as an attribute. The short form has disappeared, except in some words as rád ("content") and some forms of jeden ("one"), Sam. ("only") and possessive adjectives.

- The aorist and the imperfect have disappeared, leaving only one time past. The particle by the conditional is a vestige of the aorist.

- The past gerundium has disappeared and the past active participation, which still exists in literary language, is no longer used in everyday language.

Use

Geographic distribution

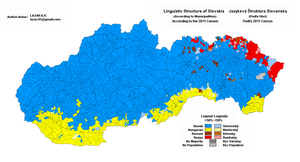

Slovak is the official language of Slovakia and one of the 24 official languages of the European Union. It is spoken throughout Slovakia, although some regions in the south of the country retain Hungarian as the majority language, despite the Slovakization policy implemented since the 19th century XX. In some municipalities in the east of the country, the majority languages are Romani and Rusino. In the 2011 census, 4,337,695 inhabitants of Slovakia (80.4% of the total population) stated that Slovak was the language they used most frequently in public (9.5% did not answer the question).

Slovak-speaking minorities exist in the following countries:

- 235.475 in the Czech Republic (2011);

- 49,796 in Serbia, of which 47,760 in the province of Voivodina, where Slovak is official in several municipalities, such as Bački Petrovac, where Slovaks represent 66% of the population.

- 44,147 in Hungary, of which 14,605 are native speakers (2011);

- 12.802 in Romania (2011);

- 10,234 in Austria (2001);

- 2.633 Slovaks of the 6,397 censuses in Ukraine speak Slovak.

Among emigrant communities, 32,227 people speak Slovak in the United States (2006-2008), 17,580 in Canada (2011), and 4,990 in Australia (2011).

The Slovak language spoken beyond the borders of Slovakia is both literary and dialectal. Slovak speeches can be found in parts of Hungary, Romania, Serbia, Ukraine, and other countries, and are often different from the varieties spoken in Slovakia. For example, in the Transcarpathian Oblast of Ukraine, local speeches have been mixed with other languages.

Relationship with the Czech

Czech and Slovak are generally mutually intelligible: it is not uncommon for a Czech and a Slovak to have a conversation in which each speaks their own language. However, since the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, Czechs and Slovaks are less exposed to the language of their neighbors (both languages were present on state television), and younger people may have difficulty understanding the other language. Czechs find it more difficult to understand Slovak than vice versa, partly because Czechs are less exposed to Slovak than Slovaks to Czech.

In Slovakia, the consumption of Czech books, audiovisual products and media remains high (Czech films are not dubbed or subtitled, except for those aimed at children), and there are even binational and bilingual television programs such as Česko Slovenská SuperStar. For its part, in the Czech Republic contact with Slovak has decreased significantly, especially in the west of the country (Bohemia).

Given the broad intelligibility between the two languages, Czech and Slovak law recognize a number of rights for speakers of Slovak and Czech, respectively. For example, the right to act in a proceeding in the other language without having to be assisted by an interpreter or the right to provide documentation without the need for translation. These rights are enshrined in the Law on Administrative Procedure of the Czech Republic and in the Law on Minority Languages of Slovakia.

Czech and Slovak differ in grammar and pronunciation. Their spelling is similar, although some letters exist only in Slovak (ä, dz, dž, ĺ, ľ, ô, ŕ) and others only in Czech (ě, ř, ů). There are also vocabulary differences:

- Some common words are very different: hovoriḳ / mluvit ("talk"), mačka / kočka ("cat"), dovidenia / nashledanou ("bye"), etc.

- There are some false friends: horký ("yellow" in Slovak, "hot" in Czech), kúriḳ / kouřit ("heating" in Slovak, "fumar" in Czech).

- The names of the months of the year are of Latin origin in Slovak (boast, february, marecand Slavic origin in Czech (leden, tuna, březenetc.).

Writing

Like the other West Slavic languages, Slovak is written with a variant of the Latin alphabet enriched with diacritics and digraphs. The Slovak alphabet has a total of 46 graphemes.

The Slovak alphabet employs four diacritics:

- the Cocktail (mäkčeň): in letters č, dž, š and ž indicates an African or a post-veolar cold; ň, ., α and . indicates the palatalization. In the last three cases it resembles an apostrophe, but it is only a typographical convention: in the capitals (except for cult) and in manual writing has the same form as in the other letters;

- the Acute accent (džeň): is used to lengthen the vowels: to, E, I, or, ?, ♪but also . and .Since l and r They can act as vowels. Unlike Spanish, it only indicates the length of the sound and not its intensity, since in the normative Slovak the prosodic accent always falls on the first syllable;

- the circumference accent (Vokáň): appears in ô e indicates the diptongo uo (the other diptongos are written with two letters: ia, ie, iu);

- the diéresis (dve bodky): on the letter ä, indicates the fonema [æ], although often this letter is pronounced as the e.

The letters q, w and x are only used in foreign words. For historical reasons, they can also be used in Slovak texts (mainly proper nouns) the Czech letters ě, ř and ů, as well as the vowels ö and ü from German and Hungarian.

Consonants are divided into three groups: hard (g, h, ch, k, d, t, n), soft (c, dz, j and all those that have caron) and neutral (b, f, l, m, p, r, s, v, z). This classification is useful to know the type of declension of nouns and adjectives. The letters i and y are pronounced identically, so the use of one or the other in writing depends on the consonant that precedes them: after a hard consonant is written y or ý (except in some adjectival endings) and after a soft consonant is written i or í. With neutral consonants, both may be possible: biť ("beat") and byť ("be") are pronounced the same. Slovak children should memorize the list of words that are written with and.

The letters d, l, n, and t are often palatalized (pronounced soft) when they are followed by e, i or í: this is why it is written ne instead of ňe, li instead of ľi, tí instead of ťí, etc. However, there are exceptions, such as in foreign words (for example, the t and the l of telefón are hard), the declension of adjectives (the n of peknej —"pretty" in feminine singular genitive — is harsh) and some common words like jeden ("one") or ten ("this"). Furthermore, the soft pronunciation of the l in this position is rarely respected today.

Pronunciation

Vowels

Slovak has five or six short and five long vowels.

| Previous | Central | Subsequential | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed | [i] i • [i devoted] I | [u] u • [u devoted] ? | |

| Semiabiertas | [ e • [engineering] E | []] or • [] devoted] or | |

| Open | ([æ] ä) | [a] a • [a devoted] to |

The vowel ä only appears after labial consonants (b, p, m, v). Its pronunciation as [æ] is archaic (or dialectal), although linguistic authorities consider it correct; today the most common is that it is pronounced [ɛ].

Diphthongs

Slovak has four diphthongs: ia, ie, iu and uo (spelled ô ).

In many words of foreign origin, for example organizácia ("organization"), the letters ia do not form a diphthong, but are two separate vowels. In these words the combinations of "i + vowel" they are pronounced with a j inserted between the two vowels: organizácija. The diphthongs ia, ie and iu can only appear after soft consonants.

Vowel Length

Vowel length is important in Slovak as it allows distinguishing minimal pairs such as vina ("culpa") and vína ("wines"), mala ("[she] had") and malá ("little"), sud ("barrel") and súd ("juzgado").

Certain suffixes and cases cause the lengthening of the preceding vowel, and in these circumstances the diphthongs ia, ie and ô can be considered as long equivalents of ä, e and o: the genitive plural of dolina ("valle&# 34;) is dolin, but the one for hora ("mountain") is hôr. Ó is found only in foreign words and interjections, and é in foreign words, adjective endings and a few words of Slovak origin (dcéra & #34;daughter"and its derivatives).

Rhythmic Rule

A pronunciation rule that is characteristic of Slovak and that differs from other Slavic languages is the so-called rhythmic rule, which establishes that, with some exceptions, there cannot be two long vowels in two syllables in a row (a diphthong counts as a long vowel). If two long syllables follow one another, the second is usually shortened, for example:

- krátky ("cut"): normally "y" would also be written with džeň (adjective termination is -KýI mean, ♪ krátký, but this is avoided with rhythmic rule, given that kra It's already a long syllable;

- biely ("white"): here bie It is already a long syllable (ie is a diptongo), so the "y" does not carry džeň.

This rule causes changes in many inflections of verbs, nouns, and adjectives: for example, the present first-person singular form of most verbs ending in -ať is normally -ám (hľadať: "look for", hľadám: "[I] look for"), but becomes -am if the verb stem ends in a long syllable (váhať: "doubt", váham: "[I] doubt"). This rule has numerous exceptions, including:

- neutral nouns completed in -Oh.: lístie ("follage");

- the plural genitive - Yeah. of some female nouns: feet ("from the songs");

- termination - Yeah. of the third person of the plural of some verbs: riešia ("[they] solve");

- adjectives derived from animal names: vtáčí "Wake, bird."

- the suffix - krát ("sees"): prvýkrát ("for the first time").

Syllabic consonants

The consonants R and L can act as vowels in words like vlk ("wolf") or zmrzlina ("ice cream"), or for example in the tongue twister Strč prst skrz krk ("Poke your finger down your throat"). They are called syllabic consonants. Like other vowels, these sounds can be lengthened: vŕba ("willow"), kĺb ("articulation").

Consonants

Slovak has 27 consonants:

| Labiales | Alveolar | Postalveolars | Palatals | Dollars | Gloss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasales | [m] m | [n] n | []] ň | ||||

| Occlusive | Deaf | [p] p | [t] t | [c] . | [k] k | ||

| Sonoras | [b] b | [d] d | []] . | []] g | |||

| Africa | Deaf | [t supporting] c | [t implied] č | ||||

| Sonoras | [d flipz] dz | [d impetus] dž | |||||

| Fellowship | Deaf | [f] f | [s] s | [CHUCKLES] š | [x] ch | ||

| Sonoras | [v] v | [z] z | [ ž | [ h | |||

| Approximately | [j] j | ||||||

| Lateral | [l] l | []] α | |||||

| Multiple vibrator | [r] r | ||||||

The consonants q, w, and x are only used in words of foreign origin.

The consonant v is pronounced [u̯] syllable-final (except before n or ň): slovo ("word") is pronounced [ˈslɔvɔ], but its genitive plural slov is pronounced [ˈslɔu̯], which rhymes with zlou (& "bad" in instrumental).

Assimilation

Most consonants in Slovak form pairs of voiceless and voiced consonants. This classification is independent of the classification into hard and soft consonants.

| Sound consonants | b | d | . | dz | dž | g | h | v | z | ž |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaf consonants | p | t | . | c | č | k | ch | f | s | š |

The consonants j, l, ľ, m, n, ň and r are phonetically voiced but have no voiceless equivalent and are not involved in assimilation within words.

As in other Slavic languages, consonants undergo final devoicing: when a voiced consonant is found at the end of a word, it is pronounced as the corresponding voiceless consonant. For example, prút ("vara") and prúd ("current") have the same pronunciation: [pruːt]. The difference between these two words is evident in the other cases: in the plural, prúty and prúdy are pronounced differently.

Consonants are also assimilated inside words: in a group of consonants, the sonority depends on the last one:

- vták ("bird"), ►ažký ("fishing") and obchod ("store") are pronounced respectively fták, Оašký and opchot;

- kde ("where") and kresba ("drawing") are pronounced respectively g.e and krezba.

This assimilation does not occur when the last consonant of the cluster is v: tvoj ("tu / tuyo") is pronounced as is written.

These rules also apply to words that are pronounced together, especially prepositions and the words that follow them: bez teba ("without you") is pronounced besťeba. The final consonant is voiceless even when the following word begins with a vowel or a consonantal sound with no voiceless equivalent (m, l, etc.): ak môžeš ("if you can") is pronounced ag môžeš.

There are other assimilation rules regarding the point of articulation of consonants:

- n in front of the k or gLike in banka ("bank"): [.

- n becomes [m] in front of b or p: Haba [engineering]

- groups ►t, t, d, ňn, l, etc. are simplified: odtia sense ("from there") and vinník ("culpable") pronounced oculoia dimension and viňňík respectively.

Alternation of consonants

Many suffixes of derivation, and sometimes of declension and conjugation, cause changes in the preceding consonants, the most frequent being the following:

- k → č, h → ž, g → ž, ch → š (first palatalization): plakaḳ ("sleep") → plačem ("[I] cry"), such ("seco") → sušiḳ ("drop"), kniha ("book") → knižka ("book");

- k → c, ch → s (second palatalization): Slovák ("Slovak") → Slováci ("slovaks"), Čech ("check") → Česi ("checos")

- s → š, z → ž, c → č, dz → dž: obec ("municip") → občan ("citizen"), Nizky ("low") → nižší ("lower"), česa ("sin") → češem ("[I] sin");

- ► → c, ^ → dz: vrátiḳ ("back", perfectivo) → vracaḳ ("return", imperfective);

- ► → t, quot → d, ň → n: šesť ("seis") → šestka ("number six"), kuchyňa ("cocina") → kuchynský (" cooking").

Prosody

The tonic stress falls on the first syllable of the word. When a word is preceded by a preposition, it is the preposition that is stressed. Clitics (see Syntax) are never stressed.

Words with more than three syllables may have a weaker secondary stress on the third or fourth syllable: this is the case, for example, with the words ˈobý ˌvateľ ("inhabitant") and ˈdemokraˌtický ("democratic").

In the Slovak language, the prosodic intonation of sentences, the rhythm of speech and pauses play an important role. Falling intonation is characteristic of affirmative or interrogative sentences beginning with an interrogative pronoun, and rising intonation is found in interrogative sentences without an interrogative pronoun.

Grammar

Like most Slavic languages, Slovak is a fusion language with numerous declensions and conjugations. Nouns are classified into three genders (masculine —in some cases distinguishing between animate and inanimate masculine—, feminine and neuter) and adjectives agree in gender and number.

Cases

In Slovak there are six cases:

- the nomination (nominativ) is the basic form given by the dictionaries, indicates the subject;

- the genitive (genitív) indicates possession;

- the harmful (dativ) indicates the complement of indirect object;

- the accusing (akuzatív) indicates the direct object;

- the crazy (Lokál) is only used after certain prepositions;

- the instrumental instruments (inštrumentál) expresses a circumstantial complement of instrument; it is also used in some cases to indicate the attribute of the subject.

In addition, all cases (except the nominative) can follow a preposition: for example, s ("with") requires the use of the instrumental and podľa ("according to") must be followed by the genitive.

The vocative (vokatív), archaic in modern Slovak, has been replaced by the nominative. Today its form is found in only a few words, such as boh — bože ("god"), človek — človeče (" person"), chlap — chlape ("boy"), kmotor — kmotre ("godfather"), syn — synu / synku ("son"), among others.

Nouns (including proper names), adjectives, pronouns, and numerals are declined.

Nouns

Slovak nouns necessarily belong to one of three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine or neuter. Most of the time it is It is possible to guess the gender of a noun based on its ending:

- the vast majority of male nouns end in consonant. Some animated nouns with male meaning end in - Yeah. (hrdina Hero, tourist, etc.) or in - (are family terms as finger "abuelito" or diminutives of stack names as Mišo, derived from Michal);

- Most female nouns end in - Yeah.. Some end up in a soft consonant (often - What?or, more rarely, in another consonant (zem"land");

- The neutral nouns end in -, - Hey., -Oh. or -a/ä. Neutral nouns in - Yeah. they are quite rare and almost all refer to animal babies (including dievča "girl" and dieťa "boy").

In the case of masculine nouns, a distinction is also made between animate and inanimate nouns: words denoting people are animate, and the others are inanimate. Animals are generally considered to be animate in the singular and inanimate in the plural. Animacy influences declensions, especially the accusative: for animate masculine nouns, the accusative is identical to the genitive, while for inanimate it is identical to the nominative.

Some nouns called pluralia tantum only exist in the plural, even if they designate a single object: nohavice ("trousers"), nožnice ("scissors"), dvere ("door"), as well as many city names: Košice, Michalovce, Topoľčany, etc.

Noun declension is complex: traditionally twelve declension patterns are distinguished, four for each gender, with many variations and exceptions. Six cases and two numbers give a total of twelve possibilities, but nouns always have fewer than twelve different forms because there are cases that are identical to others. As an example, a paradigm for each genre is presented below:

| Gender | Male | Female | Neutral | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translation | "roble" | "woman" | "city" | |||

| Name | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| Nominative | dub | duband | žena | ženand | mestor | mestto |

| Genitivo | duba | dubov | ženand | žien | mesta | miest |

| Dative | dubu | dubom | žene | žena | mestu | mesta |

| Acute | dub | duband | ženu | ženand | mestor | mestto |

| Locative | dube | duboch | žene | ženach | meste | mestach |

| Instrumental | dubom | dubmy | ženou | ženami | mestom | mestami |

Adjectives

Adjectives agree in gender, number, and case. Epithets precede the noun to which they refer (veľký dom: "big house"), except in some special cases such as the scientific names of living beings (for example, pstruh dúhový: "rainbow trout").

The declension of qualifying adjectives is regular. There are two patterns:

- the adjectives whose root ends in hard consonant: pekný, Pekná, pekné ("bonito");

- the adjectives whose root ends in soft consonant: cudzí, cudzia, cudzie ("extranjero").

| Number | Singular | Plural | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | Neutral | Female | Male | Neutral | Female | ||

| Animated | Inanimate | Animated | Inanimate | |||||

| Nominative | pekn♪ | peknE | peknto | peknI | peknE | |||

| Genitivo | peknEho | peknej | pekných | |||||

| Dative | peknEmu | peknej | pekným | |||||

| Acute | peknEho | pekn♪ | peknE | pekn? | pekných | peknE | ||

| Locative | peknom | peknej | pekných | |||||

| Instrumental | pekným | peknou | peknými | |||||

There are also some adjectives derived from animal names, such as páví ("of the peacock"). They are declined as cudzí, even though their root ends in a hard consonant, and they do not respect the rhythmic rule.

The comparative is formed by adding the suffix -ší or -ejší: dlhý ("long") → dlhší ("longer"), silný ("stronger") → silnejší ("stronger"). In the case of adjectives ending in -oký or -eký, this ending is usually dropped: hlboký → hlbší ("deep → deeper"). There are some irregularities: dobrý → lepší ("good → better"), zlý → horší ("bad → worse"), veľký → väčší ("big → bigger"), malý → menší ("small → minor").

The superlative is formed in the regular way, adding the prefix naj- to the comparative: najlepší ("the best"), najsilnejší ("the strongest").

There are also possessive adjectives in Slovak derived from personal names. They end in -ov if the owner is masculine and in -in if it is feminine: otcov ("of the father"), matkin ("of the mother"). Its declension is different from that of other adjectives.

Adverbs

Most adverbs are derived from adjectives, using the suffixes -o and -e: dobrý → dobre ("good → good"), hlboký → hlboko ("deep → deeply"), rýchly → rýchlo or rýchle ("fast → quickly"), etc. Adverbs derived from adjectives ending in -ský and -cký end in -sky and -cky: matematický → matematicky ("mathematician → mathematically").

These adverbs form the comparative and superlative in the same way as adjectives, with the ending -(ej)šie (identical to the neuter form of the adjective): hlbšie ("deeper"), najrýchlejšie ("lo faster"). There are some irregularities:

- kill him. ("small") → Men ("less"),

- sees ("much") → viac ("more"),

- skoro ("soon") → skôr or skorej ("more soon"),

- „aleko ("far off") → ♫ ("more far"),

- ve ("very") → väčšmi ("more").

Many adverbs come from the combination of a preposition with a noun or adjective: zďaleka ("from afar"), napravo ("to the right"), oddávna ("for a long time").

Verbs

Slovak verbs are conjugated according to tense, mood, voice, person (1st, 2nd, 3rd) and number (singular, plural), and have a perfective or imperfective aspect.

Verbs are divided into fourteen groups, grouped in turn into five classes, according to the way they are conjugated in the present (or future perfective). With the exception of some irregular verbs, it is enough to know the third person singular and plural to be able to conjugate the verb in all persons.

Appearance

Aspect is an essential feature of the Slovak verb: every verb is necessarily perfective or imperfective. The perfective aspect indicates a completed action (and therefore perfective verbs do not have a present), while the imperfective aspect indicates an action in progress. Thus, the phrase "Yesterday I read a book" can be translated in two different ways:

- Včera som čítal knihu. The verb is imperfect, so the important information is process: "I was reading a book yesterday." This phrase can be an answer to the question "What did you do yesterday?"

- Včera som prečítal knihu. The verb is perfectivo, so the important information is result: the action has been done completely, yesterday I finished reading the book.

A Spanish verb usually corresponds to a pair of Slovak verbs. Each form must be learned, as there are several ways to form the perfective from the imperfective or vice versa, and it is not always possible to guess whether a given verb is perfective or imperfective.

- As seen in the example phrase, the perfectivo is often formed by adding a prefix: robiť → urobiť ("do"), písa → napísa ("write"), . → poakovaḳ ("thank you").

- Some imperfectives form by adding a suffix to a perfectivo, especially when the perfectivo already has a prefix: prerušiť → prerušova ("interrupt"), da → dávaculo ("dar"), skry → skrýva ("sconder").

- In a few cases, the two verbs are completely different: klásť/položiḳ ("put"), bra/vzia ("take").

Present

Only imperfective verbs can be conjugated in the present.

| Person | by ("ḳser") | vola ("lear") | robi ("Diacer") | kupovaḳ ("buy") | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1. a | som | vol.a | stealím | kupujem |

| 2nd | Yeah. | vol.aš | stealíš | kupuješ | |

| 3a | Heh. | vol.to | stealI | kupuje | |

| Plural | 1. a | sme | vol.love me | stealGet me. | kupujeme |

| 2nd | ste | vol.ate | stealGet up. | kupujete | |

| 3a | Su | vol.ajú | stealia | kupuj? | |

Preterite

The preterite is formed with the auxiliary byť ("ser"), except in the third person, and a preterite form ending in -l that agrees in gender and number with the subject.

| Person | Male | Female | Neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1. a | bad som | bad som | - |

| 2nd | bad. | bad. | - | |

| 3a | Bad. | Bad. | Bad. | |

| Plural | 1. a | mali sme | ||

| 2nd | mali ste | |||

| 3a | Mali | |||

There is also a pluperfect past tense, which is formed in the same way from the past tense of byť: bol som napísal ("I had written"). It is only used in literary language.

Future

There are several ways to shape the future.

- The perfective verbs have no form of present: by combining them the same way as the imperfective verbs in present, the future is obtained: píšem (imperfective: "written"), napíšem (perfective: "I will write").

- By has a different form of future: Budem, budeš, bude, Bud., Buddle, Budu.

- For imperfective verbs the future of verb is used by followed by the infinitive: Budem písa ("I will write").

- Some imperfective motion verbs form the future with prefix po-. This is the case, for example, of ísť ("ir"): pôjdem, pôjdeš, pôjdeetc.

Conditional

The conditional is formed by placing the particle by before the preterite form: bol som ("yo era") → bol by som ("I would be"), except after conjunctions such as aby (" para que") and keby ("si"), since they already contain this particle. In some cases, the conditional corresponds to the Spanish subjunctive: Chcem, aby ste vedeli ("I want [you] to know").

Imperative

The imperative is formed by removing the ending -ú/-ia from the third person plural: kupovať ("buy& #34;) → kupujú ("buy") → kupuj ("buy [you]"). The first and second person plurals are formed by adding the endings -me and -te, respectively: kupujme ("buy"), kupujte ("buy&# 3. 4;). In some cases an -i is added for euphonic reasons: the imperative of spať ("sleep"; spia: & #34;sleep") is spi.

When the stem ends in d, t, n or l, the final consonant is softened: mlieť ("grind") → melú → meľ. When it ends in -ij or -yj, the -j disappears: piť ("drink" 34;) → pij-ú → pi, zakryť ("cover") → zakryj-ú → zakry.

There are also some irregularities: the imperative of byť is buď.

Denial

The negation is formed with the prefix ne-, which goes before the verb and attached to it: chcem (" I want") → nechcem ("I don't want"). In the future imperfective, the prefix is attached to the auxiliary: nebudem spať ("I will not sleep"), and in the past it is attached to the verb: nevideli sme ("we did not see"). The only exception to this rule is the verb byť in the present, since its negation is formed with the word nie: nie som, nie si, nie je, etc.

Pronouns

Slovak pronouns are declined in the same cases as nouns and adjectives.

Personal pronouns

As in Spanish, personal subject pronouns are usually omitted, since the verb form already indicates the person.

| Person | Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. a | Ha! | my | |

| 2. a | ty | vy | |

| 3. a | Male | on | oni |

| Female | ona | ony | |

| Neutral | on | ||

In some cases, there are two forms for personal pronouns: a long and a short. The long form is used at the beginning of a sentence to emphasize the pronoun and also after a preposition. Compare, for example, the two possible forms of the dative of ja: Nehovor mi to! ("Don't tell me! ") and Mne to nehovor! ("It's not me you have to tell it to!& #34;).

Treatment formulas work as follows: ty corresponds to "you" and vy can mean both "you" like "you", so it is used to address one or more people in a polite way.

There is also a reflexive pronoun, sa (it does not have a nominative, the form sa is accusative). As in other Slavic languages, it is used for all persons. Thus, the verb volať sa ("call oneself") is conjugated: volám sa, volaš sa, volá sa... which would correspond in Spanish to " I my name is, "your name is, "he is called"..., etc

Possessive pronouns

Possessive pronouns are derived from personal pronouns:

| Person | Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. a | môj | Naš | |

| 2. a | tvoj | váš | |

| 3. a | Male | Jeho | ich |

| Neutral | |||

| Female | j | ||

| Reflective | svoj | ||

Third person possessive pronouns (jej, jeho, ich) are indeclinable, since they come from the genitive forms of personal pronouns. The others are declined in a similar way to adjectives.

Possessive pronouns are identical to possessive adjectives: môj can mean both "mi" like "mine".

Demonstrative pronouns

The base demonstrative pronoun is ten (feminine tá and neuter to): este, esta. It is identical to the corresponding demonstrative adjective, and is often used to indicate that a noun is definite, since there are no articles in Slovak. This pronoun is declined in a similar way to adjectives.

The demonstrative pronouns and adjectives tento ("east"), tenže ("the same", archaic) and tamten ("that one") and its familiar synonym henten are declined in the same way. The elements -to, -že, tam-, and hen- are invariable: táto, toto;, taže, tože; tamta, tamto; hentá, hento etc. The pronoun onen, oná, ono ("that") is declined as ten.

Other pronouns

The main interrogative pronouns are čo ("what"), kto ("who"), kde ("where"), kam ("where"), kedy ("when"), koľko ("how much"), ako ("how / in what way"), aký ("how / what kind of"), ktorý ("what"), čí ("whose"), etc. The last three are declined like adjectives, čo and kto have their own declension.

Interrogative pronouns, especially čo and ktorý, also serve as relative pronouns: to, čo chcem ("what I want"), človek, ktorý vie všetko ("the man who knows everything").

Interrogative pronouns are also used to create many other pronouns through affixes:

- Nie- ("something"): niekto ("someone"), Niečo ("something"), niekde ("somewhere"), niekedy ("sometimes"), nejaký ("some"), niektoré ("some, several");

- No. (negative): nikto ("nobody"), nič ("nothing"), nikde ("nowhere"), Nikdy ("never"), nijaký ("nothing");

- -ko sensevek ("anything"): ktoko sensevek ("whoever"), čoko sensevek ("whatever," "anything"), akýko sensevek ("anyone");

- in(o)-: ("other"): inde ("in another place"), inokedy ("at another time");

- všeli- ("all kinds of", often pejorative): všelijaký ("all kinds"), všelikto ("anyone, the first to come").

Numerals

Slovak has several types of numerals, with complex declensions.

Cardinal numbers

The cardinal numbers in Slovak are:

- jeden (1), dva (2), Tri (3), štyri (4), päť (5), šesť (6), compensation (7), osem (8), deväḳ (9), desa (10);

- jedenás (11), dvanásḳ (12), trinás (13), štrnás (14), pätnás (15), šestnás (16), sedemnás (17), osemnás (18), devätnás (19);

- dvadsa (20), tridsa (30), štyridsa (40), päťdesiat (50), šesťdesiat (60), sedemdesiat (70), osemdesiat (80), deväťdesiat (90);

- sto (100), Tisic (1,000).

The numbers from 21 to 29, from 31 to 39, etc., are formed by juxtaposing the ten and the unit: štyridsaťdva (42). Hundreds and thousands are formed in the same way: tristo (300), päťtisíc (5,000). In the case of 200 and 2,000, dve (feminine and neuter form) is used instead of dva (inanimate masculine form): dvesto and dvetisíc. Compound numerals are written without spaces, which can lead to quite long words: for example, 123.456 is written stodvadsaťtritisícštyristopäťdesiatšesť.

Most cardinal numerals are declinable (although in some cases declination is optional, such as numbers made up of a ten and a unit) and can agree in gender. The words million and milliarda function as nouns. When counting (for example, with your fingers) jeden is used instead of raz ("once").

In the nominative (and in the accusative, except in the animate masculine), numerals 2 to 4 are followed by the plural nominative, and from 5 onwards by the genitive: for example, with kniha ("book") would proceed as follows: jedna kniha, dve, tri, štyri knihy, päť kníh. In other cases, the noun that follows the numeral is in the same case as the numeral.

Ordinal numbers

The ordinal numbers are:

- prvý (1o), druhý (2o), ♪ (3o), štvrtý (4th), piaty (5th), šiesty (6th), siedmy (7th), ôsmy (8th), deviaty (9th), desiaty (10o);

- jedenásty (11th), dvanásty (12th), trinásty (13th), etc;

- dvadsiaty (20th), tridsiaty (30th), štyridsiaty (40th) päťdesiaty (50o), etc;

- stý (100o), Tisici (1000o).

All these numerals are declined as adjectives. Ordinals from 21 to 29, from 31 to 39, etc., are written in two words: dvadsiate prvé storočie ("the 21st century"). In writing, ordinals are abbreviated with a period: 1. (1st), 2. (2nd), etc.

Other numerals

Among the other types of numerals in Slovak, the following stand out:

- The collective numerals (dvoje, trout, štvoro, pätoro, etc.), always followed by the plural genitive, are used to count objects that come in groups. Your use is mandatory with pluralia tantum: dvoje dverí ("two doors"), pätoro rukavíc ("five pairs of gloves").

- Numbers in -aký (adjectives) or - ako (adverbs) express a certain number of classes or types: storako ("a hundred ways"), dvojaký ("two-class").

- Multiple numerals express a certain number of times. They can form with the suffixes - No. (trojnásobný: "triple"), -mo. (dvojmo: "duplicated"), - Hey. (dvojitý: "double"), - krát (trikrátThree times, mnohokrát: "many times") or with the word raz ("sees"): dva razy ("two times"), päḳ ráz ("five times").

There are also nouns for numbers: jednotka, dvojka, trojka, štvorka, päťka etc For example, päťka means "a/the five", that is, it can refer to the number 5, or also to an object that bears it (colloquially, if the context is sufficiently of course): a school grade, the number 5 bus, the number 5 room, a 5 euro bill, etc.

Prepositions

Prepositions in Slovak are necessarily followed by a case other than the nominative. The case that governs each preposition must be learned with it, for example:

- k ("do, a"), v.aka ("thank you"), proti ("against, against") are followed by the dative;

- bez ("without"), do ("up, inside, in"), u ("in, next to"), z ("of"), od ("from, from") are followed by the genitive;

- cez ("through, above"), pre ("for") are followed by the accuser;

- pri ("near") is followed by the locative;

- s ("with") is followed by the instrumental.

Some prepositions can be followed by more than one case, which changes their meaning: na followed by the locative indicates "en" without movement, and with the accusative indicates movement: Som na pošte (locative): "I am at the post office", but Idem na poštu (accusative): "I am going to the post office". Nad ("above"), pod ("below"), pred ("in front") and medzi ("between") work in a similar way, except that the position without movement is indicated by the instrumental.

Prepositions ending in a consonant (especially those with only one consonant) have a variant with an extra vowel added to avoid unpronounceable results. Thus, v ("en") becomes vo before f or v: v Nemecku ("in Germany") but vo Francúzsku ("in France").

In addition to the above prepositions, there are prepositions derived from nouns such as vďaka ("thanks to", but also "gratitude") or pomocou ("with the help of, through, by virtue of", from pomoc instrumental "help"), prepositional phrases (na rozdiel od: "unlike") and prepositions derived from gerunds (začínajúc: "beginning with, from", from the gerund from začínať "begin").

Syntax

The order of the elements in the Slovak sentence is quite flexible, but the neuter order is usually SVO; for example, Pes pohrýzol poštára ("The dog bit the postman"). The order OVS is also considered neutral, but emphasizes the object: Poštára pohrýzol pes would translate as "The postman was bitten by a dog". Other orders are possible, but less common: Pes poštára pohrýzol emphasizes that it was a dog (and not something else) that bit the postman. Within the nominal group, however, the order of the elements is fixed: veľmi veľký dom ("a very big house") cannot be expressed in another order.

Enclitics cannot start a sentence and are usually placed in second position: they are the particle by, the forms of byť used as auxiliaries (som, si, sme, ste), reflexive pronouns (sa, si) and the short form of some personal pronouns (mi, ma, ti, ťa, ho, mu). If there are several enclitics, they should be placed in the order in which they have been cited: To by sa mi páčilo ("I would like that").

The "yes or no" they also have free word order, and usually only intonation distinguishes a question from a statement. In questions with an interrogative pronoun, this is usually placed at the beginning of the sentence (after a possible preposition): Čo chcete dnes robiť? ("What do you want to do today?").

Double negative is mandatory in Slovak: en Nikdy nikomu nič ne poviem ("I will never tell anyone anything"), all words are negative.

Vocabulary

Word formation

In general, a Slovak word can be made up of four elements: prefix(s), root, suffix(s) and ending. Prefixes and suffixes change the meaning of the root, and the ending is the element that changes when the word is conjugated or declined.

| Prefix | Raíz | Sufijo | Disincentive |

|---|---|---|---|

| I can... | zem | -n- | - Mm-hmm. |

| sub- | earth | adjective suffix | termination of adjectives |

There are also compound words in which the roots are usually joined by the vowel -o-:

- us. ("nose") + roh ("body") = us.orrožec ("rinoceronte"),

- voda ("water") + Vodiculo ("drive") = vodorvod ("channeling"),

- jazyk ("language") + Call ("romper") = jazykor♪ ("trabalenguas"),

- dlhý ("largo") + doba ("period") = dlhorDobý ("long term").

Prefixes

Prefixes are used a lot, especially with verbs. Although most prefixes have a general meaning, sometimes the meaning of the derived verb may be impossible to deduce. Thus, starting from písať ("write"), ísť ("go"), spať ("sleep") or piť (" drink"), it can form, among others:

- na-: napísa ("write", perfectivo), - ("find"), napiḳ sa ("off the thirst");

- pre- (repetition, through): prepísa ("rewrite", "transcribe"), prespať "to spend a while sleeping," "to get up";

- vy- (exit, action made to the end): vypísa ("copying [of a text]", "run [the paper, the pencil...] by writing"), vyjs ("exit") vyspaḳ sa ("deep sleep") vypiḳ ("integer drink," "purchase the glass");

- o(b)- (over, around): opísa ("describe"), obíscic ("roaring," "turning"), opiḳ sa ("screw");

- do- (finding an action): dopísa ("end of writing"), dôjsť ("take to," "achieving"), Two. ("sleep to a certain hour"), dopiḳ ("terminate drinking", "terminate drinking");

- od- (from): odpísa ("responder in writing"), odísculo ("sing", "shumming", "partir"), odpiḳ ("Brink a drink").

These prefixes can also be used with nouns and adjectives (often in words derived from verbs): východ ("exit"), odchod ("departure"), opis ("description"), etc.

Other prefixes are used primarily with nouns and adjectives, for example:

- proti- ("against"): protiklad ("contrary"), protiústavný ("inconstitutional")

- nad- ("on"): nadzvukový ("ultrasonic"), nadmerný ("excessive");

- I can... ("low"): podpora ("sport", "support"), podmorský ("submarine")

- medzi- ("between"): medzinárodný ("international").

Suffixes

Suffixes in Slovak are very often used to form new nouns derived from verbs, adjectives or other nouns. Some examples are:

- Male sufijos:

- -te sense (professions, agents): prekladate sense ("translator"), wellrovate dimension ("observer"), čitate dimension ("lector");

- - Okay. (agents, people characterized by a particular trait): hlupák ("tone"), spevák ("sing"), pravák ("extra");

- -ec (agents, inhabitants): športovec ("deporter"), Stonec ("Estonian"), lenivec ("lazy")

- - going/ (professions, agents): rybár ("fisher"), zubár ("dentist"), fajčiar ("fumator")

- -(č)an (inhabitants): Američan ("American"), Číňan ("chino"), občan ("citizen").

- Female suffixes:

- - areň/-iareň (places): kaviareň ("cafeteria"), lekáreň ("pharmacy"), čakáreň ("waiting room")

- - girl (places): čajovňa ("tea curtain"), dielňa ("taller");

- - you guys. (qualities): ml ("juventud"), dôležitos ("importance"), radosť ("joy");

- suffixes to create the female equivalent of a male word:

- -ka for most male nouns finished in consonant: zubárka ("the dentist"), čitate senseka ("reader"), speváčka ("the singer");

- -(k)yňa for most male nouns completed in -(c)a: kolegyňa ("the colleague"), športovkyňa ("the sportsman"), sudkyňa ("the judge").

- Neutral suffixes:

- -isko (places): letisko ("airport"), feetkovisko ("arenero"), ohnisko ("fogon");

- - You know what? (qualities, collective substantives): neludstvo ("humanity"), priate dimensionsstvo ("friend"), bratstvo ("brotherhood")

- -Give it. (instruments): čerpadlo ("bomb"), svietidlo ("light"), Umývadlo ("lavabo").

The most frequent adjectival suffixes are:

- -ový: malinový ("Frembuesa"), cukrový ("sugar," "sugared"), kovový ("metallic"), atómový ("atomic");

- - No.: Narodný ("national"), Hudobný ("musical"), drevený ("wood"), nočný ("nocturno")

- -ský/-cký: občiansky ("civil"), matematický ("mathematic"), školský ("school"), mestský ("urban").

Diminutives and Augmentatives

Diminutives are very common in Slovak and can apply to almost any noun. Although sometimes they only indicate that the object in question is smaller (for example, lyžička "cucharita" is actually a small spoon; lyžica), in most cases they bring an affective nuance: calling one's mother mamička ("mamaíta") instead of mama indicates a higher degree privacy, regardless of size. In restaurants, waiters sometimes offer a polievočka ("sopita") instead of a simple polievka ("soup"). The main diminutive suffixes are:

- Male sufijos:

- - Okay. pohárik ("pack"), psik ("dog");

- -ček: domček ("house"), stromček ("arbolite")

- - Okay.: kvietok ("flower").

- Female suffixes:

- -ka: knižka ("book"), žienka ("woman");

- - ička: vodička ("agüita"), pesnička ("cancioncita");

- -očka: polievočka ("sopite").

- Neutral suffixes:

- -ko: vinko ("vinito"), jabčko ("manzanite")

- -íčko: autíčko ("cotch"), slovíčko ("palabrita").

It is possible to apply several diminutive suffixes to the same noun: diera ("hole"), dierka ("little hole"), dieročka ("very small hole"). Diminutives are used especially when addressing small children.

As in Spanish, some diminutives have become lexicalized and have lost their affective meaning: for example, lístok comes from list ("hoja") and, depending on the context, can mean "ticket", "[transportation] ticket", "ticket" or "ballot", without any connotative nuance.

Augmentatives are formed with the suffix -isko (chlapisko: "big man"). They often add a pejorative undertone (dievčisko: "bad girl").

Loans

The basis of the Slovak vocabulary is the lexical fund of Proto-Slavic. Throughout history, its vocabulary has been enriched with loanwords from more than 30 languages. Among the oldest loanwords are those from Latin and Greek (for example, cultisms such as matematika, chemia, demokracia, federácia...), German and Hungarian. German and Hungarian loanwords have been introduced into the Slovak language with greater or lesser intensity for centuries as a result of continuous interlingual contacts. Of the Western European languages, English has had the most influence on the Slovak vocabulary, and to this day it remains the main source of loanwords. Slovak has also adopted loanwords from Romanian, French, Italian, and other languages. Most of the Slavic loanwords come from Czech.

As a brief summary, Slovak has borrowed words from the following languages:

- Latin and Greek: religious words like cintorlin ("cementerio") of the vulgar Latin cīmītēriumor kláštor ("monasterio" claustrum), but also very widespread words in many European languages (protokol, kalendár...);

- German: The first loans of the ancient German high began to enter the Slovak already in the ninth and tenth centuries. Often these loans (germanisms) were not original, but in turn came from Latin. For example: mních ("monage") ≤3. munih - lt. monicus. The bulk of germanisms reached Slovakia by the hand of the German settlers in the 12th-XIV centuries. In general, these are words that refer to various areas of society, the economy and everyday life. For example, góf ("conde", de Graf), rytier ("caballero" by Ritter), hoblík ("garlopa, carpenter brush" Hobel), handel ("trade"), krstiḳ ("baptize", probably related to ancient German christenen), f plasmaaša ("botella", de Flasche), jarmok ("feria", de jārmarketin modern German Jahrmarkt), minca ("moneda", by Münze), šnúra ("cuerda", de Schnuretc. Later, in the XV-XVII centuries, there was also a significant influx of germanism;

- Hungarian: Hungarian loans (magiarismos) began to join the Slovak in the centuryXII and often refer to objects and instruments of everyday life, as gombík ("button," diminutive gomb, Hungarian word with the same meaning), pohár ("vaso", identical to the word Hungarian), belčov ("cuna", de bölcsőor korbáč ("latigo" by korbács);

- Romanian: in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries several words of valac origin were incorporated into the Slovak. It is usually about "carpathisms", that is, words related to the ovine cattle breeding originating from the language of the valacos shepherds. For example: bryndza (de) brânză"cheese"), Salaš ("cranny"), Valach ("pastor")

- Czech: from the centuryXIV the Slovak has introduced a multitude of Czech loans (bohemisms) from various fields: otázka ("question"), udalos ("death"), všeobecný ("general, universal"), etc. Czech loans are often very difficult to identify because they have been adopted as well or have been evicted with minimal changes (such as dôležitý "important" důležitý). Today they are common in colloquial language: Diky (colloquial gratitude) is as frequent as its Slovak equivalent v.akaand hranolky ("fried potatoes") is more common than its official Slovak translation hranolčeky;

- French: bufet ("buffet"), portrét ("port"), interfering ("interior"), montáž ("mount"), Garáž ("garage");

- Italian: mainly musical terms adagio, bass ("low"), intermezzoetc.

- English: džús "zumo" juice), džem "mermelada" ha.) and many words concerning science, technology, sports and popular culture, such as skener ("scaner"), futbal ("ball"), klub ("club"), džez ("jazz"), vikend ("end of week" weekendetc.

Foreign nouns are assigned a gender based on their ending. Some nouns are not easily adaptable to Slovak grammar and have an unpredictable gender: alibi and menu are neuter. Adjectives usually take the suffix -ný or -ový (termálny, "thermal"), and almost all verbs they have the suffix -ovať (kontrolovať, "to control").

Examples

| Word | Translation | Transcription in AFI |

|---|---|---|

| earth | zem | [engineering] |

| Heaven | nebo | [engineering] |

| water | voda | [GRUNTING] |

| Fire | oheň | [engineering] |

| child | chlapec | [^xlap signals] |

| man | muž | [crying] |

| woman | žena | [хорики] |

| eat | jesculo | [engineering] |

| drink | piť | [ Idiot] |

| Big | See | [. |

| Little | I'm sorry. | [^mali marking] |

| night | noc | [^n]t savings] |

| Day | of | [engineering] |

| Good morning. | dobrý deň | [.......] |

Dialects

There are several dialects in Slovakia, which fall into three main groups: West Slovak (closer to Czech), Central Slovak (on which Czech is based, the literary language) and East Slovak. The three form an unbroken dialect continuum. Their use, however, tends to decline; standard, or literary, Slovak is the only one used in education and the media. The dialect groups differ mainly in phonology, vocabulary and intonation. Syntactic differences are less relevant.

A fourth dialect group is sometimes mentioned, the so-called "lowland dialects" (dolnozemské nárečia, referring to the Pannonian Plain), spoken in present-day southeastern Hungary (around Békéscsaba), Vojvodina (Serbia), western Romania and Croatian Sirmia, that is, outside the borders of present-day Slovakia. This fourth dialect group is often not considered a separate group, but rather a subgroup of the West and Central Slovak dialects, although it is currently undergoing changes due to contact with surrounding languages (Serbo-Croatian, Romanian, and Hungarian) and their long geographical separation. and politics of Slovakia.

The dialects of Slovak are further divided into several languages or subdialects. This considerable dialectal fragmentation of Slovak can be explained by several factors, such as the relative isolation of certain mountainous regions, migrations of the Slovak population, which gave give rise to a mixture of dialect types, or contacts of certain dialects with other languages (Slavic and non-Slavic).

The generational transmission of dialects is mainly oral, as only standard Slovak is taught in schools. Nowadays its daily use has been restricted to the inhabitants of rural areas, although it is common to find local dialectal features in the colloquial oral language of urban areas. In addition to oral communication, in Slovak literature (including contemporary) the use of dialectal forms is frequent; dialectal features are used in the texts (mainly in colloquial speech) to characterize the characters and create a "local atmosphere". Literature in dialect is also published.

West Slovak

West Slovak is spoken in the area of Kysuce, Bratislava, Esztergom, Komárno, Nitra and Trenčín. It shares characteristics with Czech, especially with the Moravian dialects.

- The rhythmic rule does not exist in these dialects.

- Almost all yers They've become e: rež ("centen", standard: raž).

- The nasal vowel *ę has evolved a or to (laughs) ä There is no): But ("carne", standard: mäso).

- the α does not exist and is systematically replaced l.

- There are no diptongos: ô becomes or or ?, ie in E or I.

- La v at the end of the word is pronounced f.

- Neutral nouns completed in - Hey. end up in -: vajco ("bone", standard: vajce).

- The termination of the female instrumentality is - Wow. or -U. instead of -.

- The termination of the infinitive is -t instead of - What?.

- The denial of by in the present time forms with neni instead of Nie.

- Termination - Yeah. of the plural male animated nouns becomes - Yeah. or -Here..

Central Slovak

Central Slovak dialects are spoken in Liptov, Orava, Turiec, Tekov, Hont, Novohrad, Gemer and Zvolen regions. Since Standard Slovak has developed on the basis of Central Slovak (especially the dialect spoken in the Martin area), this group of dialects is the closest to the literary language. However, there are some differences:

- La -l of the verbs in the past becomes - Wow.: dau ("[he] gave", standard: dal).

- It may appear. ä behind consonants other than lipids: kämeň ("stone", standard: kameň).

- Consonant groups tl and dl simplified to l.

- Neutral termination of adjectives is - Wow. instead of - Yeah..

- The third person of the plural by That's it. sa instead of Su.

East Slovak

The eastern dialect varieties are spoken in the area of Spiš, Šariš, Zemplín and Abov, and are the furthest from the literary language. Some characteristics relate them to Polish.

- There are no long vowels. Diptongos are simplified in most areas.

- Almost all yers They've become e: oves ("avena", standard: ovos).

- The nasal vowel ♪ has evolved to e or ia: Meso ("carne", standard: mäso).

- La v at the end of the word is pronounced f.

- Silabical consonants do not exist and instead a vowel is inserted: verch ("cumbre", standard: vrch).

- . and . pronounced c and dz: dzeci ("children," standard: deti).

- Neutral nouns completed in - Hey. end up in -: vajco ("bone", standard: vajce).

- The possessive pronouns in the plural nominative end in -: mojo dzeci ("my children," standard: moje deti).

- The genitive and the plural locative of the names ends in -och. in all genders. The plural dative is - for all genders, while in the standard Slovak this termination is restricted to male nouns.

- The past by That's it. bul instead of bowl.

- "What" is said co instead of čo.

Regulations

Standard or Literary Slovak (spisovná slovenčina) is regulated by Law 270/1995 of the National Council of the Slovak Republic on the State Language of the Slovak Republic ("Law on State Language"). According to this law, the Ministry of Culture approves and publishes the codified form of Slovak at the initiative of Slovak language institutes specialized in the field of the state language. Traditionally, this task has fallen to the Ľudovit Štúr Institute of Linguistics, which is part of the Slovak Academy of Sciences. In practice, the Ministry of Culture publishes a regulation (the one currently in force was published on March 15, 2021) prescribing the authorized reference works governing the official use of Slovak. These are:

- Ján Doru sensea et al. (sequent editions of J. Kačala J., M. Pisarčíková et al.): Krátky slovník slovenského jazyka. ["Breve Slovak language dictionary"] (abr. KSSJ):

- 1.a edition: Veda, Bratislava, 1987.

- 2.a edition: Veda, Bratislava, 1989

- 3.a edition: Veda, Bratislava, 1997

- 4.a edition: Veda, Bratislava, 2003, online version: slovnik.juls.savba.sk + slovnik.juls.savba.sk (PDF; 493 kB)

- 5.a edition: Vydavate sensestvo Matice slovenskej, Martin, 2020, without online version.

- Several authors: Pravidlá slovenského pravopisu. ["Slovak spelling rules"] (Apr. PSP):

- 1.a edition: Státní nakladatelství, Prague, 1931.

- 1.a ("2.a") edition: Matica slovenská, Martin, 1940

- 1.a ("3.a") - 11.a ("13.a") edition: Vydavate sensestvo SAV, Bratislava, 1953-1971

- 1.a edition ("14.a"): Veda, Bratislava, 1991

- 2.a edition ("15.a"): Veda, Bratislava, 1998

- 3.a edition ("16.a"): Veda, Bratislava, 2000,

- 4.a edition ("17.a"): Veda, Bratislava, 2013, online version: juls.savba.sk