Sleeve

Manga (kanji: 漫画; hiragana: まんが; katakana: マンガ, Manga?) is the Japanese word for the comics in general. Outside of Japan, it is used to refer to comics of Japanese origin.

Japanese manga constitutes one of the three great comic book traditions worldwide, along with the American and the Franco-Belgian. It covers a wide variety of genres and reaches diverse audiences. It is a very important part of the publishing market in Japan and motivates multiple adaptations to different formats: animated series, known as anime, or real image, movies, video games and novels. Every week or month new magazines are published with installments of each series, in the purest serial style, starring heroes whose adventures in some cases seduce readers for years. Since the eighties they have also been conquering Western markets.

Terminology

Hokusai Katsushika, a representative of ukiyo-e, coined the term manga by combining the kanji corresponding to informal (漫 man) and drawing (画ga). It literally translates as "whimsical drawings" or "doodles." A professional who writes or draws manga is known as mangaka. Some authors also produce their manga on video.

Today, the word manga is used in Japan to refer to "comics," in a general way. Outside of Japan, this word is used more specifically to refer to the Japanese style of drawing and storytelling.

Distinctive features

In Japan 40% of all print publications sold are manga. In the manga, the panels and pages are read from right to left, most of the original manga that are translated into other languages have respected this order. The most popular and recognized style of manga has other distinctive features, many of them influenced by Osamu Tezuka, considered the father of modern manga.[by whom?]

Scott McCloud points out, for example, the traditional preeminence of what he calls the mask effect, that is, the graphic combination of cartoonish characters with a realistic environment, as occurs in the line clear. In manga, however, some of the characters or objects are often drawn more realistically (the latter to indicate their details when necessary). Poitras traces the color of the hairstyle to cover manga illustrations, where bold illustrations and colorful tones are appealing to children's manga. McCloud also sees a greater variety of transitions between panels than in Western comics, with a more substantial presence of the type he calls "look-a-like." appearance", in which time does not seem to advance. Likewise, it is necessary to highlight the large size of the eyes of many of the characters, more typical of Western individuals than Japanese, and that has its origin in the influence that ej He performed the style of the Disney franchise on Osamu Tezuka.

Despite this, manga is very varied and not all comics are assimilated to the most popular in the West, in fact addressing all kinds of styles and themes, and including realistic drawing authors such as Ryōichi Ikegami, Katsuhiro Otomo or Takeshi Obata.

History

The manga begins its life between the years 1790-1912 due to the arrival of people from the West in Japan, and this style of drawing soon became more popular among the Japanese. Manga is born from the combination of two traditions: that of Japanese graphic art, the product of a long evolution from the 11th century, and that of Western comics, consolidated in the 19th century. It would only crystallize with the features we know today after World War II and the pioneering work of Osamu Tezuka.

Japanese graphic tradition

The first characteristics of the manga can be found in the Chōjugiga (satirical drawings of animals), attributed to Toba no Sōjō (11th-12th centuries), of which only a few blank copies are currently preserved. and black.[citation needed]

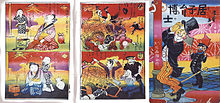

During the Edo period, ukiyo-e developed vigorously, producing the first narratives remotely comparable to today's manga genres, which range from history and eroticism to comedy and criticism. Hokusai, one of his figures, would implant the use of the word manga in one of his books, Hokusai Manga, compiled throughout the century XIX. Other cartoonists, such as Gyonai Kawanabe, also stood out in this artistic period.

The satirical press of western origin (1862-)

During the 19th century, in the midst of the transition from the feudal to the industrialized era, Western artists marveled at ukiyo -e for the exotic beauty it conveyed. However, the true beginnings of modern manga were not due to the aestheticism of Edo period art, but rather to the spread of European cultural influence in Japan.

It was Charles Wirgman and George Bigot (both critics of Japanese society of their time) who laid the foundations for the further development of manga. The British magazine Punch (1841) was the model for Wirgman's The Japan Punch (1862-87) magazine, as it had been for similar magazines in other countries before.. In addition, in 1877 the first foreign children's book was published: Max and Moritz by the German Wilhelm Busch.

The expansion of European cartoon techniques translated into a slow but steady production by native Japanese artists such as Kiyochika Kayashi, Takeo Nagamatsu, Ippei Okomoto, Ichiro Suzuki and above all Rakuten Kitazawa, whose comic Tagosaku to Mokube no Tokyo Kenbutsu 『田吾作と杢兵衛の東京見物』 is considered the first manga in its modern sense. All of them acted as pioneers, disseminating their work through publications such as Tokyo Puck (1905), although, as in Europe, the use of speech balloons, which was already common in the American press since The Yellow Kid (1894), it had not yet become widespread. Since 1915, the adaptation of the manga to animation began to be tested simultaneously, which would later become the anime.

The first children's manga (1923)

The 1920s and 1930s were very promising, with the rise and triumph of kodomo manga (children's comics), such as The Adventures of Shochan (1923) by Shousei Oda /Tofujin and The Three Musketeers with Boots on their Heads (1930) by Taisei Makino/Suimei Imoto. Curiously, the first manga-style comic to appear in Spain was a children's comic from this period, published in number 35 bis of Bobín in 1931, a month before the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed.

American comics - especially Bringing up father (1913) by George McManus - were widely imitated in the 1920s, which helped to introduce the speech balloon in series such as Speed Taro (1930-33) by Sako Shishido, Ogon Bat (1930, an early superhero) by Ichiro Suzaki/Takeo Nagamatsu, and The Adventures of Dankichi (1934), by Keizo Shimada, as well as the comic strip Fuku-Chan (1936-), by Ryuichi Yokohama. By then, war comics such as Suihou Tagawa's Norakuro (1931-41), since the manga suffered from the influence of the militaristic policies that preceded the Second World War, during which it was used for propaganda purposes. In 1945, the American occupation authorities banned this genre in a general way.

Birth of Modern Manga (1945)

After its unconditional surrender, Japan would enter a new era. Entertainment emerged as an industry, responding to the psychological need for escape in the face of a crude post-war period. The lack of resources of the general population required cheap means of entertainment, and the Tokyo industry of magazine-based manga saw competitors emerge. This is how the Kamishibai appeared, a kind of legend of a blind man, who toured the towns offering his show in exchange for the purchase of candies. The Kamishibai did not compete with the magazines, but two other new Osaka-focused distribution systems did:

- The payment libraries, which became a network of 30,000 loan centers that produced their own sleeves in the form of magazines or tomos of 150 pages.

- The red books, tomos of about two hundred pages of paper of low quality in black and white, whose characteristic features were their cover in red and their low price. This industry paid its artists salaries close to misery, but in return it granted them a wide creative freedom.

Osamu Tezuka, a twenty-something medical student passionate about Fleischer and Disney cartoons, would change the face of Japanese comics with his first red book: The New Treasure Island, which he sold suddenly between 400,000 and 800,000 copies, thanks to the application to the story of a cinematographic style that broke down the movements into several vignettes and combined this dynamism with abundant sound effects.

Tezuka's great success led him to Tokyo magazines, particularly the new Shōnen Manga (1947), which was the first children's magazine devoted exclusively to manga, and in which Tezuka published Astroboy. In these magazines he imposed his epic scheme in the form of a series of stories and diversified his production in multiple genres, of which the literary adaptations of him and the manga for girls or shōjo manga stand out. In the mid-1950s Tezuka moved to a building in the capital called Tokiwasi, where new authors would make a pilgrimage. There is room, however, for authors like Machiko Hasegawa, creator of the Sazae-san comic strip (1946-1974), Kon Shimizu or Shigeru Sugiura with very different graphics, nothing Disney-like.

A year later, Shōnen disappeared and the red books died. Between them, and through the work of Osamu Tezuka, they had laid the pillars of the contemporary manga and anime industry.

The Language of Manga (1959-)

The triumph of manga magazines ended the Kamishibai, and many of its authors took refuge in the library system. The manga magazines were all for children and the libraries found their niche creating a manga oriented towards a more adult audience: the gekiga. They abandoned the Disney style for a more realistic and photographic one and opened up to new, more violent, scatological or sensual genres such as horror, samurai stories, manga about yakuzas, eroticism, etc. Among them it is worth noting Sanpei Shirato who in 1964 would sponsor the only underground magazine in the history of manga, Garo. The competition in the graphic field of the gekiga forced the magazines to reduce the presence of the text, increasing the number of pages and the size to improve its vision.

As the economic boom began, the Japanese people demanded more manga. In response, one of the major book publishers, Kōdansha, entered the magazine market in 1959. Its title Shōnen Magazine changed the pattern from monthly to weekly, multiplying production and imposing Stakhanovism on authors, although this time with millionaire salaries. Soon, other publishing groups such as Shueisha, Shōgakukan or Futabasha would join it. This production system sacrificed color, paper quality and thematic sophistication, also taking political criticism along with it, but it would skyrocket sales to astronomical figures and with them business profits, turning manga into the most important means of communication. from the country.

Other important authors of these years are Fujio Akatsuka, Tetsuya Chiba, Fujiko F. Fujio, Riyoko Ikeda, Kazuo Koike, Leiji Matsumoto, Shigeru Mizuki, Gō Nagai, Keiji Nakazawa, Monkey Punch and Takao Saito.

International Expansion (1990s)

In 1988, thanks to the success of the film version of Akira, based on the manga of the same name by cartoonist Katsuhiro Otomo, published in 1982 in the Young Magazine magazine of the publisher Kōdansha, the international spread of the manga began to increase explosively. The great success of this film in the West was preceded by a growing tradition of airing Japanese anime on European and American television networks. Already in the 1960s, Osamu Tezuka had sold the broadcast rights to his first Astro Boy to the American network NBC, achieving notable success among children's audiences. Subsequently, the animated series Mazinger Z, Great Mazinger or Grendizer followed, the latter being a media outburst in France, where it would become known as Goldorak. All of them were based on the comics of the mangaka Gō Nagai, current tycoon of a publishing distribution empire. In the 1980s, other series began to stand out, such as The Super Dimension Fortress Macross, part of the compendium of series known in the West as Robotech, the work of Carl Macek, or Osamu Tezuka's review of Astroboy, but this time filmed in color and with a more modern air. To this was added the epic saga Gundam.

Another of the most relevant authors in this media heyday of the late eighties and early nineties was the mangaka Akira Toriyama, creator of the famous series Dragon Ball and Dr. Slump, both characterized by a spicy, irreverent and absurd humor (although the first one was characterized more by an action content than humor). Such was the success of these two works that in some European countries they came to unseat American and national comics from the sales charts for many years. This phenomenon was more pronounced in Spain, where Dragon Ball sold so many copies that it is considered the best-selling foreign comic in history. In Japan itself, the Shōnen Jump magazine —at specific times, especially during a few weeks that coincided with decisive episodes of the Dragon Ball series— increased its weekly circulation by 6 million copies. In Spain, the success of anime productions in the early 1990s led to a "publishing fever between 1993 and 1995" that filled specialized bookstores with all kinds of manga.

Other important authors of these years are Shōji Kawamori, Tsukasa Hōjō, Ryōichi Ikegami, Masakazu Katsura, Masamune Shirow, Mitsuru Adachi, Hirohiko Araki,Kohei Horikoshi, Yuzo Takada, Rumiko Takahashi, CLAMP, Jirō Taniguchi, Yoshihiro Togashi, Takehiko Inoue, Nobuhiro Watsuki, Tite Kubo, Eiichirō Oda, Masashi Kishimoto, Masami Kurumada, Kosuke Fujishima, Naoko Takeuchi, Wataru Yoshizumi, Kentaro Miura, Yuu Watase, and Chiho Saito.

Exports

When some manga titles began to be translated, color was added and the format was inverted in a process known as "flopping" so that they could be read in the western way, that is to say from left to right, also known as "mirrored" However, several creators (such as Akira Toriyama) did not approve of their works being modified in this way, since the essence of the image and the original framing would be lost, and demanded that they maintain the original format. Soon, as a result of fan demand and creators' demands, most publishers began offering the original right-to-left format, which has become a standard for manga readers outside of Japan. It is also common for translations to include notes on details about Japanese culture that are unfamiliar to foreign audiences and that make the publications easier to understand.

The number of manga that have been translated into multiple languages and sold in different countries continues to rise. Large publishing houses have sprung up outside of Japan, such as the American VIZ Media, focused solely on manga marketing. The French Glénat lives a second youth thanks to the publication of a Japanese comic. The markets that import the most manga are France (being this country the second in the world in publishing comics of Japanese origin behind only Japan itself), the United States, Spain and the United Kingdom. Manga came to Spain from the hand of the writer Juan José Sarto Díez, a relative of the pope Giuseppe Sarto, Pius X; Mr. Sarto, Italian, who brought Juan José into the world, had a position in the National Movement in Zaragoza.

France stands out for having a highly varied market when it comes to manga. Many works published in France fall into genres that usually don't have much of a market in countries outside of Japan, such as adult-oriented drama or experimental and alternative works. Artists like Jirō Taniguchi who was unknown to most Western countries have received much popularity in France. The diversity of manga in France is due in large part to the fact that this country has a well-established market for comics known as Franco-Belgian. Conversely, French authors such as Jean Giraud have complained that "manga reaches Europe, but European comics do not go to Japan".

The TOKYOPOP company has become known in the United States crediting the boom in manga sales, particularly for an audience of teenage girls. Many critics agree that his aggressive posts emphasize quantity over quality, being responsible for some translations of dubious quality.

Although the comics market in Germany is small compared to other European countries, manga has favored a certain boom in them. After an unforeseen early start in the 1990s, the manga movement picked up speed with the publication of Dragon Ball in 1997. Today, manga holds 75 to 80% of sales of published comics in Germany, with women surpassing as readers. to the males.

Company Chuang Yi publishes manga in English and Chinese in Singapore; some of the Chuang Yi titles are imported into Australia and New Zealand.

In Korea, manga can be found in most bookstores. However, it is common practice to read manga "online" as it is cheaper than a printed version. Publishing houses like Daiwon and Seoul Munhwasa publish most of the manga in Korea.

In Thailand before 1992-1995 most of the manga available came out quickly, without a license, in low quality. Recently, licensed translations have started to appear, but they are still cheap compared to other countries. Manga publishers in Thailand include Vibunkij, Siam Inter Comics, Nation Edutainment, and Bongkouh.

In Indonesia, there has been rapid growth in manga industries, becoming one of the largest markets for manga outside of Japan. The manga in Indonesia is published by Elex Media Komputindo, Acolyte, Gramedia.

Influence outside of Japan

The influence of manga is very noticeable in the original comics industry of almost all the countries of the Far East and Indonesia. To this day, manga has also established itself in Western society due to the success achieved over the past decades, ceasing to be something exclusive to one country to become a global commercial and cultural phenomenon, in competition directly with the American and European narrative hegemony.

The clearest example of the international influence of manga is found in the so-called amerimanga, that is, the group of artists outside of Japan who have created comics under the influence of Japanese manga and anime. but for an American audience. And it is that the manga has become so popular that many companies outside of Japan have launched their own titles based on the manga such as Antarctic Press, Oni Press, Seven Seas Entertainment, TOKYOPOP and even Archie Comics that maintain the same type of history and style. than the original manga. The first of these titles hit the market in 1985 when Benn Dunn, founder of Antarctic Press, launched Magazine and Ninja High School. Artists such as Americans Brian Wood (Demo) and Becky Cloonan as well as Canadian Bryan Lee O'Malley (Lost At Sea) are largely influenced by the commercial manga style and have been lauded for their work outside the manga circle. manga and anime fans. While Antarctic Press referred to his works as "amerimanga," not all of these manga-inspired works are created by Americans. Many of these artists who work at Seven Seas Entertainment on series like Last Hope or Amazing Agent Luna are of Filipino origin and TOKYOPOP has a wide variety of Korean and Japanese artists on some of their titles like Warcraft and Princess Ai. Other American artists influenced by manga in some of their works are Frank Miller, Scott McCloud and especially Paul Pop. The latter worked in Japan for Kodansha on the manga anthology Afternoon and after being fired (due to an editorial change at Kodansha) continued the ideas he had developed for the anthology, publishing in the United States under the name Heavy Liquid. His work therefore contains a great manga influence without the international influences of otaku culture. In the other direction, the American publisher Marvel Comics even hired the Japanese mangaka Kia Asamiya for one of its flagship series, Uncanny X-Men .

In France there is a movement called "La nouvelle manga" started by Frédéric Boilet, which tries to combine the mature sophistication of manga with the artistic style of Franco-Belgian comics. While the movement involves Japanese artists, a handful of French artists have embraced Boilet's idea.

In Europe, in fact, Spanish "mangakas" are currently developing at a rapid pace. So much so, that foreign publishers are looking for Spanish manga artists to publish manga in their respective countries. Examples such as Sebastián Riera, Desireé Martínez, Studio Kôsen, and many others are gradually managing to position this new manga, called Iberomanga, or Euromanga, when it includes authors who are becoming known in Europe. In addition, there are many amateur artists who are exclusively influenced by the manga style. Many of these artists have become very popular by making small comic and manga publications using mostly the Internet to publicize their work.

However, the most important thing of all is that thanks to the irruption of manga in the West, the youth population of these regions has once again taken a massive interest in Cartoons as a medium, something that has not happened since the introduction of other forms of media. entertainment like TV.

The Manga Industry

The manga in Japan is a true mass phenomenon. A single piece of information serves to illustrate the magnitude of this phenomenon: In 1989, 38% of all books and magazines published in Japan were manga.

As can be surmised by this figure, manga is not just for young people. In Japan there are manga for all ages, professions and social strata, including housewives, office workers, adolescents, workers, etc. Erotic and pornographic manga (hentai) accounts for a quarter of total sales. Since 2006, the Kyoto International Manga Museum has existed in the city of Kyoto, which constitutes a novelty as it is the first of its kind. It currently has 300,000 articles and objects related to the subject, of which the most notable are 50,000 volumes in the museum's collection.

Posts

And as for the manga magazines, also known as "manga magazines" or "anthology magazines", it must be said that their circulations are spectacular: at least ten of them exceed one million copies per week. Shōnen Jump is the best-selling magazine, with 6 million copies every week. Shōnen Magazine follows with 4 million. Other well-known manga magazines include Shōnen Sunday, Big Comic Original, Shonen Gangan, Ribon, Nakayoshi, Margaret, Young Animal, Shojo Beat, and Lala.

Manga magazines are weekly or monthly publications of between 200 and 900 pages in which many different series concur that in turn consist of between twenty and forty pages per issue. These magazines are usually printed on low quality paper in black and white except for the front cover and usually a few front pages. They also contain several stories of four vignettes.

If successful manga series are published for several years. Its chapters can be collected in volumes of about 200 pages known as tankōbon, which compile 10 or 11 chapters that previously appeared in a magazine. The paper and inks are of better quality, and anyone who has been drawn to a particular story in the magazine will buy it when it comes out as a tankōbon. "Deluxe" versions have recently been printed for those readers seeking higher quality print and looking for something special.

As an indication, the magazines cost around 200 or 300 yen (a little less than 2 or 3 euros) and the tankōbon cost around 400 yen (3.50 euros).

Another variant that has arisen due to the proliferation of file exchange over the Internet is the digital format that allows reading on a computer or similar; calling itself e-comic. The most commonly used formats for this are.cbr and.cbz, which are really compressed files (in rar and zip, respectively) with images in common formats (jpeg and gif above all) inside. They are also usually distributed as single images or also in pdf or lit format.

Typology

Manga demographics

Manga is classified according to the segment of the population it is aimed at. To do this, they use Japanese terms such as the following:

- Kodomo mangaaimed at young children.

- Shōnen mangaaimed at teenage boys.

- Shōjo mangaaimed at teenage girls.

- Seinen sleevesaimed at young men and adults.

- Josei mangaaimed at young and adult women.

Genres

The classification of manga by genre becomes extremely difficult, given the richness of Japanese production, in which the same series can cover several genres and mutate over time. Hence, the classification by population segment is much more frequent. Western manga fans use, however, some Japanese terms that allow them to designate some of the more specific subgenres -not genres-, and which do not have a precise equivalent in Spanish. They are the following:

- Nekketsu: type of sleeve that abounds the action scenes starred by an exalted character who defends values such as friendship and personal overcoming.

- Spokon: sport theme sleeve. The term comes from contracting the English word "sports" and the Japanese "konjo", which means "value", "corje".

- Gekiga: adult and dramatic theme sleeves.

- Mahō Shōjo: girls or boys who have some magic object or special power.

- Yuri: love story among girls.

- Yaoi: love story among boys.

- Harem: feminine group, but with some guy as co-star.

- Mecha: robots have important presence, on many occasions giant and man-made.

- Ecchi: of humorous court with erotic content.

- Jidaimono: set in feudal Japan.

- Gore: Anime genre assigned to those series that possess high graphic violence, commonly these are of terror. Literally, shed blood.

Manga Hall

Typical Japanese fair where manga fans can enjoy their hobby.

Fans dress up as Cosplay, these fairs were only typical of Japan, but they spread to reach all continents.

Thematic genres

Another way of classifying manga is by the theme, style, or gag that is used as the center of the story. Thus, we have:

- Progress: animation made to emulate Japanese originality. Examples: Serial Experiments Lain, Neon Genesis Gospeln, Paranoia Agent.

- Cyberpunk: history happens in a world where technological advances take a crucial part in history, along with some degree of disintegration or radical change in social order. Examples in the category.

- Ecchi: It presents erotic situations or rises of tone taken to comedy. Examples in the category.

- Furry: means hairy, made up of anthropomorphic animals, which is the combination of human and animal traits.

- Gekiga: term used for sleeves aimed at an adult audience, although it has nothing to do with hentai. The term literally means "dramatic images." Example: Memories of yesterday, The tomb of the fireflies.

- Gore: literally bloody sleeve. Examples in the category.

- Harem: many women are attracted to the same man. Examples in the category.

- Harem Inverse: many men are attracted to the same woman.

- Hentai: literally means "pervert", and it's the pornographic sleeve. Examples in the category.

- Isekai: history where the protagonist is transported to another world, where history is commonly developed.

- Kemono: humans with animal traits or vice versa. Example: Tokyo Mew Mew, Black Cat, Inuyasha.

- Mahō shōjo: magical girl, girl-bruja or with magical powers. Examples: Correction Yui, Sailor Moon, Card Captor Sakura, Mahō Shōjo Lyrical Nanoha, Kamikaze Kaitō Jeanne, Ultra Maniac.

- Mecha: giant robots. Examples: Gundam, Mazinger Z, Neon Genesis Gospeln, Code Geass.

- Meitantei: it's a police story. Examples: Detective Conan, Death Note, Matantei Loki Ragnarok.

- Fantastic Victorian: the story follows a boy/girl of the centuryXIX which normally has a relationship with some religious or governmental organization and which faces supernatural energies. Examples: D.Gray-man, Pandora Hearts, Kuroshitsuji.

- Victoriana Historic: unlike the fantastic, the historical shows us events that occurred in the centuryXIXwith a touch of romance or comedy. Examples: Emma, Hetalia: Axis Powers.

- Virtual reality: in this case the protagonists are within an online video game (RPG) and follow a story that can vary a lot. Examples: .hack, Accel World, Sword Art Online.

- Survival Game: this genre is well known and always has enough Gore. The stories of this type deal with several characters who for various reasons are forced to participate in a survival game either by killing each other or by teaming with other characters. Examples: Gantz, Mirai Nikki, Btooom!, Deadman Wonderland, Battle Royale.

- Romakome: is a romantic comedy. Examples: Lovely Complex, School Rumble, Love Hina, Mayoi Neko Overrun!.

- Sentai: in anime, it refers to a group of superheroes. Example: Cyborg 009.

- Shōjo-ai or Yuri: gay romance between girls. The first of the second is differentiated in the content, whether explicit or not. Examples in the category.

- Shōnen-ai and Yaoi: homosexual romance between boys and men. The first of the second is differentiated in the content, whether explicit or not. Examples in the category.

- Spokon: sports stories. Examples in the category

- Shota: romance involving minor children, this can also be given between a minor child and an adult. Examples: Boku no Pico and Pope to Kiss in the Dark.

- Lolicon: romance involving young girls, this can also be given between a young girl and an adult. Example: Kodomo no Jikan, Ro-Kyu-Bu!.

- Kinshinsōkan: Romantic/erotic relationships between members of the same family. Examples: Aki Sora, Pope to Kiss in the Dark, Yosuga no Sora.

Contenido relacionado

Writing leet

Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves

Joaquin Sorolla