Sinogram

The Chinese characters, sometimes called sinograms (汉字/漢字, Chinese: hànzì, Japanese: kanji, Korean: hanja; literally, 'Han character'), are a logographic and originally syllabic writing system developed by the Han Chinese around the Yellow River Plain and adopted by several East Asian nations (sinosphere). Sinograms were once used by East Asian nations to write Classical Chinese text, and have since been used in Chinese and Japanese scripts, as well as Korean, Old Vietnamese, and other languages.

Chinese characters (hanzi) are morphosyllabic: each corresponds to a pronounced syllable and provides an elementary meaning; This does not happen, for example, in the Japanese kanjis. In modern Chinese, many words are bisyllabic or polysyllabic, and are therefore written with two or more sinograms, and have a meaning that is not automatically deduced from the sum of their component sinograms. Cognates between Chinese dialects have the same spelling (same sinogram) and similar meanings but often have different pronunciations.

Japanese sinograms (kanji) behave like lexemes and the grammar is complemented by Japanese syllabaries. In Japanese, a sinogram can represent several syllables. Of other national languages, Korean (hanja) stands out, which has almost completely replaced them with the Korean alphabet, but they continue to be used to disambiguate homophones, and Vietnamese (hán tự), which has completely replaced them with a new system of script, the Vietnamese alphabet, made up of Latin letters with diacritics. In these cases, the sinograms can represent only the original Chinese meaning with the pronunciation of the local language, although the pronunciation can also be derived from Chinese in the case of words borrowed from Chinese. Foreign pronunciations of Chinese characters are known as sinoxenic.

Formation Rules

Traditionally, Chinese characters are divided into six types, a division that first appears in the Shuowen Jiezi dictionary from the year 100 AD. C., by Xu Shen: Sinograms represent words of the language by various methods.

| Pictograms | Ideogram Simple. | Ideogram compound | Loan | Fonosemántico | Cognados |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manifesto Xiàngxíng zì | oriented zì | Facilitated I ran away | oriented Jiguljiè zì | Manifesto Xíngshēng zì | oriented Zhuănzhù zì |

| Mountain | ・ 日本語 Tree → Raíz

| Force + field = Male | . Back (bei) → North (bei)

| .. Change (hua) → Flor (hua)

| ̄s ” Examination / Old

|

- Pictographic characteristics or pictograms (PHEN xiàngxíng): are those who graphically represent an object; they are the easiest to recognize. Examples constitute it γ koviću “mouth”, ré “man”, 日 r "sol" and "huvic" for "fire."

- Indicative characteristics or simple ideograms zhANCE): are symbols that indicate certain phenomena and representations. They are also used to represent abstract ideas. To this category belong characters like ◄ shàng “up” or ” xià “Down.” It's also soluble. běn “raíz” or “origin”, a character that is obtained by adding a stroke to і mù “tree” at its bottom, indicating its roots.

- Associative characteristics or composite ideograms I ran away): are those created by the association of two or more ideographic characters. In this case, each character provides a different sema or unit of meaning, so they could be called semic assembly characters (which would follow the meaning of their name in Chinese, ⌘ or “composition of meanings”). An example is the character of the sequential ming “brillante”, assembled from 日本語 r “sol” and August yuè “light”, the two most brilliant celestial bodies visible in the firmament. Or 鳴 ming “voice or squeal of a bird”, composed of γ koviću “mouth” and y Niăo “bird, bird.”

- Features swipe or phonetic loan (і jiăjiè): is given above all in homophone words, in which one lends to the other the character, sometimes adding another element to distinguish the meanings. A classic example is the verbo ⋅ ♪ “to come”, which is represented with the character that indicated formerly a type of barley, lexia that was equally pronounced ♪. The principle of the loan of character to transcribe something of difficult representation, as an abstract concept, such as “coming”, or also as a foreign word, we find it in the transcription of foreign vocablos. An old example is es Pútáo “uva”, another more modern is oriented bùlājí “Western Court” ♪.

- Phnosemántic Characters (EF) xíngshēng): they are created by the association of a character that contributes the phonetic element and another that adds the semantic differentiation, called radical and that normally goes to the left. This method of phenomantic assembly was the one that triggered the combination possibilities of Chinese writing, resulting in most of the current Chinese characters being of this type. The principle works as follows: if I have the character el mā, I know something pertaining to the category No. “woman” is pronounced as ” măbeing here irrelevant the sense of “horse” of this last character. The Meaning of de mā would then be “mamamá”, using also reduced,, māma. The formula would be like this: RADICAL (continued) woman) + FONÉTICE (ON mă) = BE FEMENINE TO BE PROGRESS [ma] → → mā "Mama."

- Notative or cognated characteristics: these are those in which the meaning has been expanded to cover other similar concepts.

History

Legendary Origin

Chinese tradition attributes the invention of Chinese characters to the legendary character Cang Jie, minister of the mythical Yellow Emperor (Huang Di), who would have invented the characters inspired by the footprints of birds.

There are other less widespread legends about the origin of the characters. One of them, collected in the Laozi, locates the origin of the characters in a system of rope knots. Another legend points to the 8 Yijing trigrams, invented by the legendary sage Fu Xi, as precursors of Chinese writing characters.

Some outdated theories saw the origin of Chinese characters in the cuneiform writings of ancient Mesopotamia. Now an independent origin is already being thought of.

Early Use of Symbols

In recent decades, a number of inscribed charts and images have been found in Neolithic excavations in China, including Jiahu (c. 6500 BCE), Dadiwan and Damaidi of the sixth millennium a. C. and Banpo (fifth millennium BC). Often these findings are accompanied by media reports pushing back the supposed beginnings of Chinese writing thousands of years. However, because these marks occur singly, without any implied context, and are made from Crudely and simply, Qiu Xigui concluded that "we have no basis for asserting that they constituted script nor is there reason to conclude that they were ancestral to Shang dynasty Chinese characters." On the other hand, they demonstrate a history of signal use in the Yellow River Valley during the Neolithic to the Shang period.

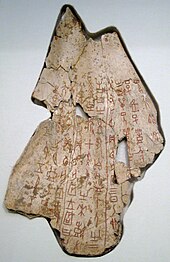

Oracle bone writing

The oldest confirmed evidence of Chinese writing discovered so far is the body of inscriptions carved on bronze vessels and oracle bones from the late Shang dynasty (c. 1250 -1050 BC). The oldest of these dates from 1200 BC. C. In 1899, pieces of these bones were sold as "dragon bones" for medicinal purposes, when scholars identified the symbols on them as Chinese script. In 1928, the source of the bones was located in a village near Anyang in Henan Province, which was excavated by the Academia Sinica between 1928 and 1937. More than 150,000 fragments.

Oracle bone inscriptions are records of divination performed in communication with actual ancestral spirits. The shortest are only a few characters, while the longest are thirty to forty characters. The Shang king communicated with his ancestors on topics related to the royal family, military success, weather forecasting, ritual sacrifices, and related topics through scapulimance, and the responses were recorded on the divination material itself.

Bone writing is a well-developed writing system, suggesting that the origins of Chinese writing may predate the late 2nd millennium BC. Although these divinatory inscriptions are the earliest evidence of ancient Chinese script, it is widely believed that it was used for many other unofficial purposes, but the materials on which they were written (probably wood and bamboo) were less durable than bone and shell, so they have been used ever since. have deteriorated.

Bronze Age

The traditional image of an ordered series of scriptures, each suddenly invented and completely displacing the previous system, has been conclusively shown to be fiction by archaeological finds and scholarly research at the turn of the century XX and early XXI. The gradual evolution and the coexistence of two or more types of characters was the most frequent case. As early as the Shang dynasty, oracle bone script existed as a simplified form alongside the normal bamboo book script (preserved in typical bronze inscriptions), as well as extra elaborate pictorial forms (often clan emblems). found in many bronzes.

Based on studies of these bronze inscriptions, it is clear that from the Shang dynasty to Western Zhou and early Eastern Zhou scripts, the main script evolved in a slow and uninterrupted manner. It eventually assumed the form now known as seals in the late Eastern Zhou script in the Qin state, without any clear dividing lines. Meanwhile, other scripts had evolved, especially in the eastern and southern areas during the dynasty. Late Zhou, including regional forms, such as the gǔwén ("older forms") of the Eastern Warring States, preserved as variant forms in the Han dynasty character dictionary, Shuowen Jiezi, as well as decorative forms such as bird and insect inscriptions.

Unification

The seal script, which had slowly evolved in the Qin state during the Eastern Zhou dynasty, was standardized and adopted as the formal system for all of China in the Qin dynasty (leading to the misconception that invented at the time), and was still widely used for decorative engraving and seals in the Han dynasty period. Despite standardization during this period, however, more than one script format remained in use at that time. moment. For example, a little-known, rectilinear, and roughly executed common (vulgar) type of script had coexisted for centuries with the more formal seal script in the state of Qin, and the popularity of this vulgar form grew as the use of the seal script grew. The script itself became more widespread. By the Warring States period, an immature form of clerical script called "early clerical" or "proto-clerical" had already developed in the state of Qin based on this vulgar script, and also with the influence of seal script. The coexistence of the three scripts, seal, vulgar and proto-clerical (gradually evolving in the Qin dynasties until early Han dynasties in the form of clerical script) goes against the traditional belief that the Qin dynasty had only one script and that the clerical system was suddenly invented in the early Han dynasty from writing on small seals.

Introduction

One of the most outstanding features is that the character usually coincides with a syllable that has meaning. This is probably the cause of the misconception that Chinese is a monosyllabic language. Actually, most of the modern Chinese lexicon is made up of two-syllabic words, understanding a word as a lexical unit that can be freely combined in a sentence. In classical Chinese, many more monosyllabic words were used, but even so, no state of the language is known in which all words were monosyllabic. In fact, there are disyllabic terms that are written with two characters that can only appear together, such as gāngà (尷尬 /尴尬, "ashamed") or jǔyǔ (齟齬 /龃龉, "altercation"). In these cases, a semantic or etymological analysis would not even be possible as a union of two morphemes.

There are various criteria for classifying the types of Chinese characters. The simplest is to divide them into three basic categories

The oldest characters are pictograms, that is, drawings of the concept they represent. For example:

The first character, pronounced ré in modern Mandarin means "person", and comes from the drawing of a human profile. This character is an authentic monosylobic word and is used in modern Chinese. The second example, pronounced mù, meant "tree" in ancient times, and depicts, stylizedly, the trunk, the cup and the roots of the tree. In modern Chinese, this character has come to mean "madera", while tree is said shù (). /).).

The first character, pronounced ré in modern Mandarin means "person", and comes from the drawing of a human profile. This character is an authentic monosylobic word and is used in modern Chinese. The second example, pronounced mù, meant "tree" in ancient times, and depicts, stylizedly, the trunk, the cup and the roots of the tree. In modern Chinese, this character has come to mean "madera", while tree is said shù (). /).).

The second type of characters are called ideograms. In these cases the pictograms are combined to suggest ideas by association. For example:

These two ideograms are based on the previous pictograms. The first, pronounced qiú, means "prisoner", meaning suggested by the image of a locked person. In modern Chinese, the normal word to say prisoner is qiúfàn (. dialogue), a form that still contains this character. The second character of the image means "bosque", idea suggested by the repetition of the tree. In this case, the modern Chinese has also ended up giving us a syllable form: The current word is sēnlin (Linked), where another similar ideogram appears with three trees.

These two ideograms are based on the previous pictograms. The first, pronounced qiú, means "prisoner", meaning suggested by the image of a locked person. In modern Chinese, the normal word to say prisoner is qiúfàn (. dialogue), a form that still contains this character. The second character of the image means "bosque", idea suggested by the repetition of the tree. In this case, the modern Chinese has also ended up giving us a syllable form: The current word is sēnlin (Linked), where another similar ideogram appears with three trees.

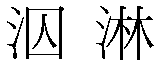

The third type of characters are logograms. This type covers the vast majority of current Chinese characters. It consists of modifying another character with which it shares pronunciation by adding another component that distinguishes it. The added component is often one of the so-called radicals, which provides a semantic idea regarding the type of meaning represented by the new character. Let's see two examples:

These two logograms are based on the previous ideograms, but correspond to completely different words. In both characters there are three strokes on the left. These strokes are known as "three drops of water", or "radical of water", and come from the pictogram that means water. Characters that have these three drops of water usually have a meaning related to water or liquids. The first, pronounced qiúIt's based on the ideogram qiú by the fact that he has the same pronunciation. Its classic meaning is "nadar" and is used little in modern Chinese. A word with this character is qiúdù (., "cross to swim"). The second character is pronounced ♪And it's because of that phonetic coincidence that it's based on the character of the forest. The three drops of water tell us that it is, however, a term related to water. Its meaning is "empapar". In modern Chinese it can be used as a monosyllable verb, or in some bisylab combinations, as in the word línyù (., "ducha").

These two logograms are based on the previous ideograms, but correspond to completely different words. In both characters there are three strokes on the left. These strokes are known as "three drops of water", or "radical of water", and come from the pictogram that means water. Characters that have these three drops of water usually have a meaning related to water or liquids. The first, pronounced qiúIt's based on the ideogram qiú by the fact that he has the same pronunciation. Its classic meaning is "nadar" and is used little in modern Chinese. A word with this character is qiúdù (., "cross to swim"). The second character is pronounced ♪And it's because of that phonetic coincidence that it's based on the character of the forest. The three drops of water tell us that it is, however, a term related to water. Its meaning is "empapar". In modern Chinese it can be used as a monosyllable verb, or in some bisylab combinations, as in the word línyù (., "ducha").

Most likely, in an ancient stage of the language these logograms began to be written with the same character whose sound they share, and that the addition of the radical occurred later to clarify the meaning, in a similar way, saving the distances, to the use that we make in Spanish of the tilde to differentiate monosyllables with different meanings, such as "si" and "yes", or "tea" and "tea".

The Chinese character system is not, therefore, an inventory of monosyllabic words, as is sometimes said, but rather a kind of huge syllabary with which the sounds of words of the spoken language are represented[citation required].

Relevant aspects of Chinese characters

- Chinese characters (traditional Chinese: s, simplified Chinese: /25070/, pinyin: hànzì) are used in Chinese language writing (although they have spread to Japanese and Korean).

- Each sign refers to the minimum unit of significance (morfema).

- In the lexicon of the vast majority of the current words are bisilables made up of the union of two monemas, which usually have their own identity and significance, for example). (welcome).

- There are inventoried about 50 000 different characters, of which 10,000 are used in the cultured language and 3000 in the current language.

- Few hanzis are ideograms and since ancient times the signs have phonetic value although these signs do not determine exactly the sound and therefore it is very difficult to know how they should be pronounced.

- Most characters are composed of a semantic radical (more or less common meaning) and a phonetic one, which takes advantage of ordering them in dictionaries.

- Each character is indivisible and invariable, but for technical and study reasons they are classified into simple and composite (according to the strokes), ideographic (deductible sense of the parts) and phonetic (if any strike indicates the pronunciation).

- Throughout history various styles of grafism have been used which are still preserved in the traditional calligraphic art: The first style of writing, which emerged during the Shang dynasty, is known as dàzhuànshū Ё, large seal writing. Other styles are the writing of the small seal (xiăozhuànshū /25070/), the clerical writing (lishu).️), the semi-cursive writing (xingshu рорик, and the style of grass (căoshū ה).

- The written style or literary language called wenyan, originated from ancient Chinese allows to understand the texts of any time.

- The style baihua closer to the spoken language and already used by Buddhism, gradually moved wenyan and replaced it completely with the educational reform of China of the centuryXX..

- The traditional form of writing was vertical and right to left but is modernly made horizontally and left to right.

- Since 1956 the government of the People's Republic of China simplified the characters and officially adopted the Pinyin transcription system in 1979. Singapore did the same thing.

- The number of Chinese characters in the dictionary Kangxi is 47.035, although many are unusual variants accumulated throughout history. Studies carried out in China have shown that full literacy in the Chinese language requires only three to four thousand characters.

Dissemination

Sinograms were born in the Chinese language and therefore it is in the Chinese script where they have their original nature. In China, the characters have been evolving, although one of the biggest changes was the introduction of simplified Chinese characters in which the number of strokes is reduced and their shapes are simplified with the declared objective of reducing their complexity and facilitating their dissemination to the common people., although they have received much criticism.

In the Republic of China (commonly called Taiwan) as well as in Hong Kong and Macao, pre-reform sinograms, called traditional Chinese characters, continue to be used.

This division does not prevent people literate in the simplified or traditional form from being able to recognize the other form with a minimum of study.

Japan Archipelago

Within the process of consolidating the Japanese language, along with the development of the syllabic alphabet, the Chinese ideographic system was adopted to express the language. The use of kanji is one of the three main forms of Japanese writing, the other two being hiragana and katakana, grouped together as kana.

The kanji are generally used to express only concepts, unlike their use in Chinese, where they can also be used in their phonetic character. A kanji corresponds to a meaning and is used as a determiner of the root of the word; derivations, conjugations, and accidents are expressed by the use of kana (especially hiragana) under the name okurigana. In this way, both the autochthonous writing system (but derived from the same Han script) and the imported system coexist.

Korean Peninsula

Hanja (Hangul: 한자; Hanja: 漢字; literally: "Han characters"), or Hanmun (한문; 漢文), sometimes translated as Sino-Korean characters, is the name given to the Chinese (Hanzi) characters in Korean, but more specifically, it refers to those characters that Koreans borrowed and incorporated into their language, changing your pronunciation. Unlike Japanese kanji characters, some of which have been simplified, most hanja are identical to traditional Chinese hanzi, although some differ slightly from the traditional form.

Today, Hanja is not used to write words of native origin, nor words of Chinese origin.

Vietnam

Hán tự (漢字, pronounced: [hǎːn tɨ̂ˀ]) or chữ Nho (𡨸儒, [cɨ̌ ɲɔ], "writing of Confucian scholars") are the Vietnamese terms for sinograms, when they were used for writing Classical Chinese, used in imperial Vietnam for formal writing, and which are undifferentiated from Classical Chinese works written in China, Korea, or Japan.

In contrast, chữ Nôm (字喃/𡨸喃/𡦂喃, pronounced: [cɨ̌ˀnom]) also used sinograms but to write in the Vietnamese language. The earliest examples date from the 13th century and were used almost exclusively by the country's elite, mostly for writing Vietnamese literature (the formal texts used to be written in classical Chinese). Currently it has been replaced by quốc ngữ, a script based on the Latin alphabet.

Contenido relacionado

Fala (Jalama Valley)

Languages of germany

Lojban