Sing of my Cid

The Cantar de mio Cid is an anonymous deed song that recounts heroic deeds loosely inspired by the last years of the life of the Castilian knight Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar el Campeador. The preserved version was composed, according to most current critics, around the year 1200.

This is the first extensive poetic work of Spanish literature and the only epic song preserved almost complete; Only the first page of the original and another two inside the codex have been lost, although the content of the existing gaps can be deduced from the chronicle prostitutions, especially from the Chronicle of Twenty Kings. In addition to the Cantar de Mio Cid, the other three texts of its genre that have endured are: the Mocedades de Rodrigo —circa 1360—, with 1700 verses; the Song of Roncesvalles —ca. 1270—, a fragment of about 100 verses; and a short inscription from a Romanesque temple, known as the Epic Epitaph of the Cid —ca. 1400?—.

The relevance of the Cantar is not limited to the literary but rather it gave rise to an entire intellectual discipline: philology as a modern science in Spain at the end of the century XIX, which begins with the study of this poem by Ramón Menéndez Pidal (1869-1968) and his decision to apply the historical-critical method to this text for the first time, the most powerful tool of the philology of his time, thus inaugurating Spanish philological studies.

The poem consists of 3735 verses of variable length (anisosyllabic), although those of fourteen to sixteen metric syllables predominate, divided into two hemistiches separated by caesura. The length of each hemistich is normally from three to eleven syllables, and is considered the minimum unit of Cantar prosody. His verses are not grouped into stanzas, but into runs; each one is a series without a fixed number of verses with one and the same assonance rhyme.

Its original title is unknown, although it would probably be called “gesta” or “cantar”, terms with which the author describes the work in lines 1085 (& #34;Aquí compieça la gesta de mio Çid el de Bivar", beginning of the second cantar) and 2276 ("las coplas deste cantar aquís van acabinando", almost at the end of the second), respectively.

Plot and structure

Internal structure

The theme of the Cantar de mio Cid is the complex process of recovering the honor lost by the hero, whose restoration will eventually mean a greater honor than the starting situation. Implicitly, it contains a harsh criticism of the high nobility of Leon by blood or court and praise for the low nobility that has achieved its status through its own merits, not inherited, and wars to achieve honor and honor.

The poem begins with the banishment of the Cid, the first reason for dishonor, because of the legal figure of the royal wrath ("the king has angered me", vv. 90 and 114), unfair because it has been provoked by intriguing liars ("by bad landowners you are thrown out", v. 267) and the consequent confiscation of their estates in Vivar, the kidnapping of their material goods and the deprivation of the homeland power of his family.

After the conquest of Alcocer, Castejón, the defeat of Count Don Remont and the final conquest of the Taifa kingdom and the city of Valencia, thanks to the courage of his arm, his cunning and prudence, he obtains royal pardon and with it a new inheritance, the Señorío de Valencia, which joins its old site already restored. To ratify his new status as lord of vassals, weddings are arranged with lineages of the greatest prestige, which are the infantes of Carrión.

But with this the new fall of the Cid's honor is produced, due to the outrage that the infantes of Carrión inflict on him in the person of his two daughters, who are harassed, whipped, badly injured and abandoned in the oak grove of Corpes to Let the wolves eat them.

This fact supposes, according to medieval law, the de facto repudiation of these by those of Carrión. For this reason, the Cid decides to allege the annulment of these marriages in a trial presided over by the king, where the infantes of Carrión are also publicly infamed and removed from the privileges they previously held as members of the royal entourage. On the contrary, the daughters of El Cid arrange marriages with kings of Spain, thus reaching the maximum possible social promotion of the hero.

Thus, the internal structure is determined by curves of obtaining-loss-restoration-loss-restoration of the hero's honor. At first, which the text does not reflect, the Cid is a good vassal knight of his king, honored and with estates in Vivar. The banishment with which the poem begins is the loss, and the first restoration, the royal pardon and the weddings of the Cid's daughters with great noblemen. The second curve would begin with the loss of honor of his daughters and would end with the reparation through the trial and weddings with kings of Spain. But the second curve exceeds in width and reaches greater height than the first.

External structure

The editors of the text, since Menéndez Pidal's 1913 edition, have divided it into three songs. It could reflect the three sessions in which the author considers it convenient for the minstrel to recite the deed. The text seems to confirm this as it separates one part from another with the words: «here conpieça la gesta de mio Çid el de Bivar» (v. 1085), and another later when it says: «The couplets of this song are ending here» (see 2276).

Plot

First sing. Song of Banishment (vv. 1–1084)

After being falsely accused of having kept the outcasts that he went to collect in Seville, El Cid is banished from Castile by King Alfonso VI. Some of his friends decide to accompany him: Álvar Fáñez, Pedro Ansúrez, Martín Antolínez, Pedro Bermúdez etc. Antolínez contributes food and gets a loan from the Jews Raquel and Vidas to finance the trip, using the rumor that Rodrigo has stayed with the outcasts to his advantage; so he leaves them two chests, actually full of sand, as a deposit and guarantee, without even telling them what is inside. The king orders that no one shelter them while they cross the border, for example in Burgos; Out of nobility, the Cid refuses to take up residence by force in an inn and camps on the outskirts. To avoid danger, he leaves his wife and daughters under the protection of Abbot Sancho of the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña, and begins a military campaign accompanied by his faithful in non-Christian lands. First he conquered Castejón and then Alcocer and, finally, he defeated Count Don Remont in the battle of Tévar, who, full of arrogance at having been captured by those "malcalçados", refuses to eat until kindly del Cid makes him give up his attitude. With each victory he sends a part of the booty (the so-called & # 34; royal fifth & # 34;) to the king, although he is not bound by having been banished, as he intends to achieve royal pardon.

Second sing. Song of the wedding of the daughters of Cid (vv. 1085–2277)

El Cid campeador goes to Valencia, held by the Moors, and manages to conquer the city. He sends his friend and right-hand man Álvar Fáñez to the court of Castile with new gifts for the king, asking her to be allowed to join his family in Valencia. The king accedes to this request, and the Cid can proudly show the city and its plains to his family from a high tower; the king even forgives him and lifts the punishment that weighed on the Campeador and his men, and so much fortune of the Cid makes the infantes of Carrión ask in marriage Doña Elvira and doña Sol (the daughters of the Cid); the same king asks the Campeador to agree to the marriage; to finish ingratiating himself with him, he agrees, although he does not trust them. Weddings are celebrated solemnly, the celebration lasts 15 days.

Third song. Song of the insult of Corpes (vv. 2278–3730)

The infants of Carrión show their cowardice before a lion that escaped from its cage, fleeing in terror. Something similar occurs in the fight with King Búcar, who seeks to recover Valencia. The captains of the retinues of El Cid hide the dishonor of the Infantes al Cid and make fun of them. Feeling humiliated, the kids decide to revenge. For this, they undertake a trip to Carrión de los Condes with their wives and, upon reaching the Corpes oak grove, they whip them and abandon them, leaving them faint, for the wolves to eat. El Cid has been dishonored and asks the King for justice. This convenes Cortes in Toledo and there the trial begins with the return of the dowry that the Cid gave to the infants: his swords Tizona and Colada, and culminates with the "riepto" or duel in which the representatives of the cause of the Cid (the same captains who had hidden the dishonor of the infants), Pedro Bermúdez and Martín Antolínez, challenged with eloquent speeches and defeated them, leaving them half dead and dishonored. Their weddings are annulled and the poem ends with the wedding project between the daughters of El Cid and the princes of Navarre and Aragon and, therefore, with the honor of El Cid at its highest point.

Features and Themes

The Cantar de mio Cid differs from the French epic in the absence of supernatural elements (except, perhaps, the appearance in dreams of the archangel Saint Gabriel to the protagonist, the episode of the lion that humiliates itself before the Campeador, the brilliance of the Colada and Tizona swords, and the extraordinary quality of Babieca), the restraint with which his hero conducts himself and the relative credibility of his exploits. The Cid offered by the Cantar constitutes a model of prudence and balance. Thus, when an immediate and bloody revenge would be expected from a prototype of an epic hero, in this work the hero takes his time to reflect upon receiving the bad news of the mistreatment of his daughters ("when they tell my Cid the Champion, / a great hour thought and ate», vv. 2827-8) and seeks its reparation in a solemn judicial process; He also rejects, as a good strategist, acting rashly in battles when circumstances advise against it. On the other hand, El Cid maintains good and friendly relations with many Muslims, such as his ally and vassal Abengalbón, which reflects his Mudejar status (the "moors of peace" of the Cantar) and the friendly and tolerant with the Spanish-Arab community, of Andalusian origin, common in the Jalón and Jiloca valleys where a good part of the text takes place.

In addition, the condition of social ascent through weapons that occurred in the borderlands with the Muslim domains is very present, which is a decisive argument in favor of the fact that it could not be composed in 1140, since at that time it was not It gave that "frontier spirit" and the consequent social rise of the proud knights of the lands of Extremadura.

The Cid himself, being only an infanzón (that is, a hidalgo of the lowest social category, compared to counts and rich men, a rank to which the infantes of Carrión belong) manages to overcome his humble social condition within the nobility, achieving prestige and wealth (honor) and finally a hereditary lordship (Valencia) and not in tenure as a royal vassal. Therefore, it can be said that the real theme is the rise of honor of the hero, who in the end is lord of vassals and creates his own House or lineage with land in Valencia, comparable to counts and rich men.

Moreover, the marriage of his daughters with princes of the kingdom of Navarra and the kingdom of Aragon indicates that his dignity is almost royal, since the lordship of Valencia emerges as a novelty in the panorama of the century XIII and could be compared to the Christian kingdoms, although, yes, the Cid of the poem never ceases to recognize himself as a vassal of the Castilian monarch, if The title of Emperor beat well, both for the two Alfonsos involved and for what was its origin in the Leonese kings, invested with imperial dignity.

In any case, the lineage of a feudal lord like El Cid is related to that of the Christian kings and, as the poem says: «Oy the kings of Spain your relatives are, / to all alcança ondra for the one who was born in good time.» («Today the kings of Spain are their relatives, / they all have honor for the one who was born in good time»), vv. 3724–3725, so that not only is his house related to kings, but they are more honored and enjoy greater prestige for being descendants of El Cid.

Regarding other epic songs, particularly French, the Song presents the hero with human features. Thus, El Cid is dismounted or misses a few blows, without losing his heroic stature. In fact, it is a narrative strategy, which by making victory more doubtful, further enhances his success.

The credibility is evident in the importance that the poem gives to the survival of an exiled retinue. As Álvar Fáñez points out in verse 673 “if we don't deal with Moors, nobody will give us bread”. The Cid's combatants fight to earn a living, which is why the Cantar details at length the descriptions of the booty and its distribution, which is done in accordance with the laws of Extremadura (that is, of border areas between Christians and Muslims) from the end of the 12th century.

Karl Vossler in his Spanischer Brief, published in the magazine Eranos, in 1924, which he addressed to Hugo von Hofmannsthal, points out that «in the Cantar we find a non-clerical soldiery spirit and a rude, optimistic environment and of victory. But, there is no rancor in him, no spirit of revenge or desire for glory and, for that very reason, nothing tragic, and yes the personal, courageous and sensible affirmation of a man of honor. There is not in the Cantar any kind of spiritual kinship with the Chançon de Roland. The French influence and all its romantic exterior loses substance when you come to understand its true essence. He adds: “greater freedom of artistic composition cannot be imagined within a more rigorous unity of ethical intention. The events, the scenes, the gestures, the speeches and the verses follow one another without continuity and in an almost cinematographic way, with strong intonation, but with an unequal number of syllables. A great drive and a surprising improvisational audacity have made the poem a work that gives us an impression of monumentality and anecdote, of something primitive or casual. A great unity and harmony must have reigned among the spirits of the time to give a firm, natural and easy coherence to such fragile and naive forms. The poet delights in the figure of the hero, in his exploits and struggles and also in the increase of his honor ».

Metric

Each verse is divided into two hemistiches by a caesura. This form, also typical of the French epic, reflects a useful resource for the recitation or singing of the poem. However, while in the French poems each verse has a regular meter of ten syllables divided into two hemistiches by a strong caesura, in the Cantar de mio Cid both the number of syllables in each verse and that of syllables in each hemistich varies considerably. This trait is called anisosyllabism.

Even though, with exceptions that are usually attributed to anomalies in textual transmission, there are verses of between nine and twenty syllables and hemistiches of between three and eleven, most of the verses range between 14 and 16 syllables.

Various interpretations of the poem's meter have been proposed. One of the most common defends that the most important element of the prosody of the Spanish medieval epic are the accentual supports and not the syllabic computation, generally postulating two tonic strokes for each hemistich. Such is the opinion of authors such as Leonard (1931), Morley (1933), Navarro Tomás (1956), Maldonado (1965), López Estrada (1982), Pellen (1994), Goncharenko (1988), Marcos Marín (1997) Duffell (2002) and Segovia (2005), which is also the most reasonable option in the opinion of Montaner Frutos, although this author points out that most of these proposals are excessively rigid, since the model The rhythm of the Cantar does not respond to a fixed pattern, but varies depending on the service to a cadence, so that, depending on the length of the verses, the number of accents per hemistich can increase or decrease, depending on the number of unstressed intervals that appear in each verse. Orduna, in 1987, postulated the presence of secondary intensity inflections, and other theories that combine various parameters are in this line. In any case, the importance of accents does not mean that you have to completely ignore the number of syllables in relation to the study gave of the meter of this poem.

In principle, all the verses rhyme in assonance, but the assonances are not totally regular or very varied (eleven types of assonance are used). What is fundamental, in any case, is the assonance of the last stressed syllable and it must be taken into account that from this last stressed syllable the vowel «e» is not considered for rhyming purposes, a phenomenon that is related to the « e» paragogic or added to words ending in a consonant in epic poetry.

The verses are grouped into runs of variable length. In Menéndez Pidal's edition, the length varies between 3 and 190 verses, each of which has the same rhyme and usually constitutes a unit of content, although the change of assonance cannot be reduced to rules. The change in rhyme can be due to a transition to another place, the more detailed development of an episode or a variation in the style of speech, the identification of the interlocutor in a dialogue, the change of the emitting voice (from the narrator to a character, for example) or the introduction of digressions.

Fonts

The Cantar de mio Cid reuses a good amount of historical news, often transformed by the literary needs of adapting the story to the genre of epic songs and to what is expected of an epic hero, and he invents another series of passages, the most outstanding being that of the affront of the infantes of Carrión, which is all fictitious, since it has not even been possible to verify the existence of these counts.

Leaving aside the unproven possibility that there could be epic songs about the Cid prior to the one that has been preserved, and rejecting the existence of some presumed "news songs", of which there is no testimony, the The main source of the Cantar would be oral history, and partly to passages that ultimately refer to the Historia Roderici, although the objection remains that the cantar de geste completely omits Rodrigo Díaz's service to the taifa kings of Zaragoza, which is recounted at considerable length in Latin biography, but the same thing happens with the panegyric hymn Carmen Campidoctoris, which also silences this period in the selection that makes of the episodes narrated in the Historia Roderici.

For other data, such as the names of historical figures, he could have also used the legal documentation of the time, in his capacity as a lawyer, although due to reminiscences of documents handled for other reasons, and not expressly resorting to archives of diplomas on Rodrigo Díaz to document the work he was writing, which is an anachronistic approach, in addition to the fact that this type of documentation does not offer the material that would be necessary to compose an epic poem. It was this composition procedure on which they based themselves the theses of Colin Smith, who defended that the author was Per Abbat, identifying him with a clergyman and jurist from Burgos.

Thus, although the author of the Cantar could secondarily receive information from legal documents and the Historia Roderici, the historical information of the Cantar de mio Cid comes mainly from oral history, whose vitality was much greater in the 12th century than it is today One might think: still in 1270, the collaborators of Alfonso X the Wise's Estoria de España handled information obtained from oral news about the time of El Cid.

If there was a tradition of Hispanic epic songs prior to that of mio Cid (something that authors such as Colin Smith deny), he would inherit his metric system, which would be a romanization of the Latin hexameter adapted with accents of intensity, rather than quantity. But the clearest influence is given with respect to the French epic of the XII century, especially the Chanson de Roland (perhaps based on a Hispanic Cantar de Roldán, of whose existence there are indications), from which he adopted, among other aspects, the formulaic system. Its echo is also perceived in other specific passages, such as verse 20 "God, what a good vassal, if you are a good lord!", the appearance of the archangel Saint Gabriel, the narrative structure of the combats and the type of warrior tactics and weapons, or the figure of the warrior bishop Jerome, parallel to that of Turpin in the French chanson de geste.

Style

The most characteristic features of the style of the epic poem of El Cid are its rhetorical sobriety, its realism and a conscious use of an archaic language typical of the cantares de geste and which constituted in fact an artificial language identified with this narrative subgenre until the present day. XIV century, as shown in the late Cantar de las mocedades de Rodrigo. The German Hispanist Karl Vossler points out in Algunos caracteres de la cultura española, that the Cantar "has a very original physiognomy, very Castilian and human, far from the French model". Edmund de Chasca highlights as features of his style "the precision and formal meaning of concrete things used as elements of a construction."

Realism, and its associated sobriety in the use of rhetoric, is important: it already sets a defining stamp on all the Spanish literature that will come later: La Celestina, the picaresque novel, the Quijote... It is reflected in the agreement and careful description of all details; The accounting of what the Cid earns as booty in each of his victories is even kept in silver marks (the currency of singing) and in horses; such prosaic details are described, such as the fact that it was cooked at the weddings of the Cid's daughters and even the color that this physiological act gives to the face: "bermejo is coming, he was having lunch", as well as all the gestures that the characters do.

The archaic and conventional language characteristic of the epic songs has caused difficulties in terms of dating the poem based solely on its linguistic features. The ancient language gave this heroic verse a venerable tinge, of intrinsic value for referring to a mythical age, to a heroic time. It would constitute a record of the sublime or grave medieval style. But in addition to archaisms, in this linguistic modality there are Latin cultisms (laudare, the ablative absolute las archas aduchas) and even Arabisms (the Arabic vocative particle ya).

At the phonic level, alliteration, internal rhymes and other euphonic effects can be seen, closely related to the oral, recited or semi-sung nature of these poems. Thus, verse 286 has been proposed as an example of alliteration ("The bells toll in San Pero a clamor") with its recurrence in the nasals, which evoke the peculiar acoustics of the bells. Of internal rhyme, the following verses can be highlighted:

Mercy, already king and lord, for love of charity!

I can't forget the greater grudge.

Hear me all the evil corts of mine,

Carrion's ifantes, who rang so badly.Singing from my Cided. by Montaner Fruits, vv. 3253-3256.

Moving to the lexical sphere, the use of expressions of the clerical and legal linguistic variety stands out, such as «curiador» ('guarantor'), «rencura» ('querella'), «intención» ('allegado') or «manfestar» ('confesar'). Also noteworthy is the use of doublets of synonyms, such as "a king and a lord", "grandes averes priso e mucho sobejanos", "a priessa vos garnid e metedos en las armas" or "he thought and ate"; A special case is the antithetical but actually synonymous doublet: "I have come to Moors, I have left is to Christians", "if it pleases you, Minaya, and I do not fall into sorrow for you", "before I will lose my body and leave my soul" or "night is past, morning is come." Parallel is the use of lexical pairs that include the reference to a whole through the conjunction of two terms that complement each other, as is the case of «big and small» (which is equivalent to 'everyone'), “el oro e la plata” ('riches of all kinds'), “by day by night” ('at all times') or “a caballeros e a peones” (' 39;to all the host'). In general, a recurring recourse to bi-member syntactic structures can be seen, which on occasions is an oxymoron ("and I'm doing him badly and he's doing me grand pro").

As for the syntax, the use of the so-called «physical phrases», which enhance the gestures, is notable. This is the case in the pleonastic expressions "crying from the eyes" or "speaking from the mouth." Syntactic and semantic parallelisms also abound, and it is common to find anaphoras and enumerations:

You saved Jonah when he fell into the sea

you saved Daniel with the lions in jail,

In Rome you saved Mr. Sabastián,

save Santa Susaña from the false criminal.vv. 339-343, ed. de Montaner Frutos.

Another notable resource is the large number of periphrastic verbal uses, among which the inchoatives querer + infinitive, tomararse a + infinitive and compeçar de + infinitive stand out. The enjambment is rarer (singing is characterized by its stichomytia), but its use is very significant in this type of literary genre.

Among the rhetorical figures, it is worth mentioning the use of question marks and exclamation marks. On the other hand, figures of thought are very rare. It is only worth mentioning a few simple metaphors, with symbolic value and a base established in tradition and oral language. A simile has usually been pointed out, the one used to compare the separation of the Cid and his family with the formula "like the nail of meat" (vv. 365 and 2642). Metonymy is more widespread, especially in its variety of synecdoche (expressing the part to allude to the whole). In verse 16 it is said that in the Cid's company there were "sessaenta pennons" (that is, sixty knights armed with lances, which ended in a banner or banner). A notable case is the expression "fardida lança" where the lance is a synecdoche of a knight and the epithet "fardida" (=ardida, 'fiery', 'brave') is actually a metaphor that personifies the virtue of the one who enlists it. Of lyrical scope are the "hairy eyes they taste everywhere", where the eyes are synecdotal metonymy of the Cid's women, who have just climbed the highest point of Valencia to contemplate the richness of the landscape that the hero has just conquered.

Formular phrases

The epic tradition has a characteristic expressive resource consisting of using certain expressions turned into set phrases that were used by minstrels as a resource that helps recitation or improvisation and that become a stylem typical of the language of songs deed. The formulaic system of the Cantar de mio Cid is strongly influenced by that of the chanson de geste of the north of France and Occitania of the twelfth century, although with renewed formulas adapted to its Hispanic spatiotemporal scope of around 1200.

The resource consists of the stereotyped repetition of set phrases and, often, delexicalized, which usually occupy a hemistich and, where appropriate, provide the word of the rhyme, so that, originally, they would have the function of solving the lagoons of improvised recitation of the minstrel. Over time it became a stylistic feature of the particular linguistic variety (Kunstsprache) of the epic genre. Some of the most frequent in Singing are:

- mio Cid 'spoleó [to his horse] mio Cid', sometimes used with another character, like "the count", v. 1077

- He put his hand in the sword/sword into his hand 'start the sword'

- by the cobdo/la loriga fasted the blood by flashing

- my pro vassallo

The epic epithet

These are fixed phrases or periphrases used to positively adjective a main character who is defined and individualized with this designation. It can be constituted by an adjective, adjective sentence or an apposition to the anthroponym with a specific function and not only an explanatory one. It is the Cid who has the greatest number of epic epithets, which ultimately form part of the system of formulas and set phrases. The most used to refer to the hero are:

- The Champion

- The one with the vellide beard (populated bar, hairy)

- The one that was born in good time

- The one who in a good hour chisel (sworded, that is, was armed knight)

But also the affections and relatives of the Cid receive epithets. Thus, the king is "the good king Don Alfonso", "ondrado king" ('honored'), "my natural lord", "the Castilian", "the one from León". Jimena, his wife, is a "wavy woman"; Martín Antolínez is the "pro/complido/contado/loyal/natural Burgos"; Álvar Fáñez (in addition to the fact that the «Minaya» that usually precedes him as a name could be an epithet), is «right hand». Even the Cid's legendary mount, Babieca, is "the horse that walks well" and "the runner"; or Valencia, which is "the clear" and "the largest".

The enunciating voice

The speech or story is emitted from the voice of an omniscient narrator who freely uses verb tenses with a stylistic function. He usually provides more information than the characters have, creating a gap between the expectations of the public and that of the protagonists that leads to what has come to be called dramatic irony; this can create comedy or give rise to conflicting tension. As an example, we can refer to the moment in which the infantes of Carrión took the daughters of El Cid. The audience knows that they plan to mistreat them but not the hero, who lets them go from his protection. On the other hand, a case of comedy is the episode of the loan of the coffers to the Jews Rachel and Vidas; the public knows, with the Cid, that they are mostly filled with sand, but the greedy lenders imagine it full of riches.

The narrator always positions himself in favor of the Cid (he takes sides in his joy at the arrival, thanks to the Campeador, of the bishopric in Valencia: «God, how happy all Christianity was, / that in the lands of Valencia, sir, I avié bishop !», vv. 1305–1306), and against his antagonists, such as the Count of Barcelona, whom he calls petulant. In order to seek complicity with the audience, the narrator sometimes abandons the third person to address the listeners with appellative formulas in the second person or referring to himself in the first person. For example, when the weddings of the Cid's daughters are celebrated in Valencia, he exclaims before his audience: "sabor abriedes de ser e de comer en el palacio", v. 2208 ('You would love to be and eat in the palace').

The Manuscript

There is a single headless copy (that is, the one that lacks the beginning, in codicology) that is currently in the National Library in Madrid and can be consulted in the Hispanic Digital Library and in the Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library. In addition to the initial folio, it is missing two others, of about fifty verses each, after verses 2337 and 3507. The three gaps can be reconstructed by means of the prosifications of the chronicles. The first is transcribed into two: the Estoria de España and the Crónica de Castilla. In the Estoria de España ordered to be written by Alfonso X the Wise, it says as follows:

- Et él después que ovo leídas las cartas, como quier que ende oviese gran pese, non wanted ý ál fazer, ca non avié periodo más de nine días en que saliese. He opened for his relatives and for his vassals, and told them how the king sends him out of his land and that non le dava of term more than nine days, and that I wanted to know what he wanted to go with him or what to fake. Minaya Álvar Fáñez told him: “Cid, we will all go convusco and servos have loyal vassals.” All the others said that they would go with him wherever he was, and that he would not be taken away by any guise. The Cid graded it stews a lot, and tell them that if God pleased him, that gelo rewarded very well. Another day the Cid de Bivar came out with all his scooter...

The Crónica de Castilla says more or less the same thing, but keeping some assonant rhymes due to poor prosification:

- He opened the Cid for all his friends and his relatives and vassals, and showed them how the king sent him to save from the earth nine days ago. Exodus: “Friends, I want to know what you want to go with. And those that I eat are strong, of God are good enough for you, and those who finance here, I want to go your wages.” Estence fabló Álvar Fáñez, his cormanian cousin: “We will all go, Cid, for we and for towns, and you will never die as soon as we are biased and healthy, conbusco despender the mules and the cavallos, the averes and the cloths; you will always serve as loyal friends and vassals.” Estence bestowed all that Alvaro Fáñez gave, and so much my Cid graded them as it was reasoned there. [...] And the Cid took the bird, moved with his friends from Bivar.

For the second and third gaps, only the Estoria de España can be used; the second goes like this:

- The Cid, when he heard it, smiled a little and dixote to the infants: “enforzad infants of Carrion and non temades nada. Be in Valencia to your taste.” When they were in this, King Búcar said to the Cid that he should send him to Valencia and leave in peace, and if not, that I have sinned him as much as I have warned. The Cid dixo said that he brought the message: “Give Búcar that fi de enemiga that before the three days I will give him what he demands.” Another day he sent the Cid to arm all his own and went out to the Moors. Carrion's infants then asked for the lead. And after the Cid ovo stops his azes, Don Ferrando, the one of the infants, went forward for ferring to a moro dezien Aladraf. The Moor when I saw it, was against him others, and the infant with the grant fear that ovo d’él turned the rein and fuxo, which only did not dare to wait. But Bermudez, who iva cerca d’él, when he saw it, was to ferret in the Moor and bound him and killed him. He took the digging of the moro and was the empos of the infant that iva fuiendo e dixole: “don Ferrando, take this digger and dezir all that you did kill the moro whose era, and I convusco bestow it.” The infant told him: “don But Bermúdez, much you bloke what you see dezides

The third gap is filled with the following text:

- Sir, ruegovos that these diggers that I here you exodus that I am flung to Valencia. And therefore you have good that this lid is in Carrion, I want to go to Valencia.” Estence sent the Cid to the commanders of the infants of Navarre and Aragon beasts and all the things that they need were ovated, and embroidered them. King Don Alfonso stumbled upon all the high omnes of his court to go out with the Cid that went out of the village. And when they came to Çocodover, the Cid going in his cell that dezién Babieca, the king said: “don Rodrigo, faith that you turn that you repent of that cavallo that I heard so much dezir.” The Cid turned to smile and dixote: “Sir, here in your court there are many high omens and stews to fazer this, and those mandats that stumble with their diggers.” The king told him: “Cid, I pay for what you see dezides, but I want every way you run that digger for my love.” The Cid snatched the digger, so rezio ran it that everyone marveled at the run I set. Then I come the Cid to the rrey and tell him to take that cello.

In the 16th century, the manuscript was kept in the Vivar Council Archive. Later it is known that she was in a convent of nuns in the same town. Ruiz de Ulibarri made a handwritten copy in 1596. Eugenio de Llaguno y Amírola, secretary of Carlos III's Council of State, took it from there in 1779 for publication by Tomás Antonio Sánchez. When the edition was finished, Mr. Llaguno retained it in his possession. He later passed on to his heirs. He later passed on to the Arabist Pascual de Gayangos and during that time, around 1858, he saw it and consulted Damas-Hinard to make an edition. He was then sent to Boston to be seen by the Hispanist Ticknor, a friend of Gayangos. In 1863 the first Marquis de Pidal already owned it (by purchase) and while in his possession, Florencio Janer studied it. It was later inherited by his son Alejandro Pidal, who had a piece of furniture built in the shape of a medieval castle to guard the chest where the manuscript was kept. Karl Vollmöller, Gottfried Baist, Huntington and Ramón Menéndez Pidal, the latter a relative of the owner, studied it in his house. Valued in 1913 at 250,000 pesetas, the Pidal family decided to transfer the manuscript to a box in the Bank of Spain. It remained there until the Civil War, when it was sent to Geneva along with other works of art, including those in the Prado Museum. With the end of the conflict he returned to Spain. Since the end of the XIX century, the Pidal family has received numerous purchase requests from abroad, including from the British Museum in London. A famous case was the attempt of the Hispanicist Archer Milton Huntington, founder of the Hispanic Society of New York, who gave Alejandro Pidal a blank check so that he could write the number he wanted in exchange for obtaining the manuscript in order to deposit it in the Washington Library. However, the Pidals refused for decades to sell the manuscript. It was finally acquired by the Juan March Foundation from the Pidal family on December 20, 1960 for ten million pesetas of the time and on the 30th of that same month it was donated to the Ministry of Culture, which attached it to the National Library.

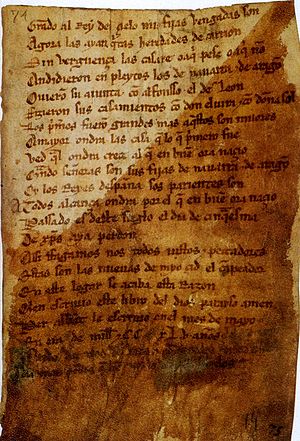

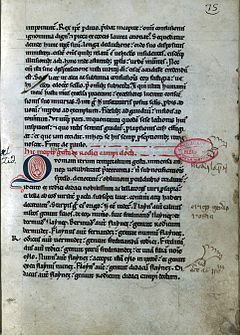

It is a volume of 74 sheets of thick parchment, which, as has already been said, is missing three: one at the beginning and two between sheets 47 and 48 the first, and 69 and 70 the third. Other 2 leaves serve as guards. The manuscript is a followed text without separation into songs, nor space between the verses and the spreads, which always begin with a capital letter according to custom. On many of its pages there are dark brown stains, due to the reagents used since the XVI century to read what At first, it had turned pale and, later, it was hidden due to the blackening produced by the chemical products previously used. In any case, the number of absolutely illegible passages is not too high and in such cases, in addition to Menéndez Pidal's paleographic edition, there is a copy of Ulibarri from the century XVI and other editions prior to Pidal's.

The binding of the volume is from the 15th century century. It is made of board lined with sheepskin and with stamped borders. There are remains of two closing hands. The sheets are divided into 11 notebooks; the first one is missing the first leaf; the seventh is missing another, the same as the tenth. The last binder made some major flaws in the tome.

The handwriting of the manuscript is clear, and each line begins with a capital letter. Occasionally there is capital letter. The latest studies ensure that, after analyzing all relevant aspects, the codex belongs to the first half of the XIV century, more specifically between 1320 and 1330, and preferably in the last five years of this decade, and was possibly prepared or commissioned by the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña from a pre-existing copy of the Cantar taken on loan.

Dating

It is only extant in a copy made in the XIV century (as deduced from the handwriting of the manuscript) from from another that dates from 1207 and was carried out by a copyist named Per Abbat, who transcribed a text probably composed a few years before this date.

The date of the copy made by Per Abbat in 1207 can be deduced from the date reflected in the explicit of the manuscript: "MCC XLV" (from the Hispanic era, that is, for the current dating, you have to subtract 38 years).

Who wrote this book of God paradise, love

Per Abbat wrote to him in the month of May in the era of a thousand e. CC XLV years.

This colophon reflects the usage of medieval scribes, who when they finished their work of transcribing the text (which was what "write" meant), added their name and the date they finished their work.

The author and the date of composition

Based on the analysis of numerous aspects of the preserved text, literary critics attribute it to an educated author, with precise knowledge of the law in force at the end of the 12th century and beginning of the 13th, and who could be related (due to his knowledge of microtoponymy) with the area surrounding Burgos, Medinaceli (current Soria), the border area of Castilla with Aragon, the Alcarria or the Jiloca valley. Philologists, however, such as Diego Catalán, based on the interpretation of the structure social, or Francisco Marcos Marín, based on linguistic data that support the existence of a previous version, linguistically more archaic, with vestiges of -d < -t in the third person, for example, argue for the need for an earlier, unpreserved version written in the mid-XII century.

- The language used is that of a cult author, a lawyer who had to work for some cancery or at least as a notary of some noble or monastery, since he knows the legal and administrative language with technical precision, and who dominates several records, among them, of course, the style proper of medieval-breeding songs, which needed certain exclusive styles, such as the epic epithet or the language to formulate.

- The geography provides another data: the fact that Medinaceli appears as a definitive Castilian square, and not as a border city in dispute between several border kingdoms, can only refer to the second half of the centuryXII. For example, in 1140 it was Aragonese.

- The society reflected in the Song the validity of the “border spirit”, which was only given in the Aragonese and Castilian extremes at the end of the centuryXIIbecause the war needs at the borders allowed the infanzones the conditions of rapid social promotion and relative independence that had the hidalgos of the border that we see in the Song and that were historically given from the conquest of Teruel. The status of "moros en paz" of the Cid, i.e., the first Mudejars, necessary in territories with little Christian population, such as the extreme soriana and turolean.

- The right shows that the detailed technical description of the courts or views refers to the "requirement" or trial with singular combat, institution influenced by Roman law, and only introduced in Spain at the end of the centuryXII. Likewise, the presence of the legislation of the Aragonese and Castilian extremes (the rages of Teruel and Cuenca date back to the end of the XII and the beginning of the XIII respectively) take us as soon as 1170.

- The sigilography tells us that the royal seal (the "carta... fortress sealed" of vv. 42-43) is only documented under the reign of Alfonso VIII of Castile from 1175.

- From the point of view of the herald, which reaches the Iberian peninsula by 1150, appears on the Song the symbolic use (oversign) with the ornate in the overvest of the knights, a robe that put on the dress. This emblematic use has its testimony earlier in a stamp of Alfonso II of Aragon of 1186.

- From sociology and diachronic lexicography, the oldest testimony of the term "fijodalgo" (hidalgo) refers to 1177, and that of "rich man" to 1194.

- In the Middle Ages “write” meant only “to be the copist”, for what we know today as the author would say “compuso” or “fizo”. This invalidates Colin Smith's theory that the author was Per Abbat, although, as it is logical, it assumes that the date of composition could not be later than 1207, however it is very little behind the original wording.

Pidal gave the date of the explicit 1307, arguing that there would be a third 'C' erased in the manuscript, following the conjecture of the first editor of the Cantar Tomás Antonio Sánchez (1779). been able to observe the slightest ink trace of an erased "C". Montaner uses all the technical means at his disposal, including infrared vision. Most likely, the copyist hesitated and left a little more space just in case (as he does in other places in the poem) or tried to avoid some imperfections in the parchment. It could also be that he made two very small incisions with the scraping knife (cultellum) that was used for corrections, since these have indeed been observed under a microscope, and they are straight incisions (not an erasure scratch as he defended Menéndez Pidal, which would leave the texture rough) that could have induced the copyist to avoid that space so that the ink would not run over the crack. Pidal himself will come to admit that there would not be that third "C" erased, because, in any case, the texture defect of the manuscript or "the wrinkle" according to him would be prior to the writing. For him, Per Abbat would be a copyist of a text from 1140, but the argument of the popular diffusion of the Cidian genealogy also works against him, since the Cid did not become related to all the Spanish dynasties until the year 1201; It was also based on the fact that a Latin poem mentions El Cid, the Poema de Almería, but this is of uncertain dating (it could be from the end of the XII century) and, above all, it does not allude to Singing , but Cid himself, who was already known for his exploits. As for archaisms, it is clear, as Russell and other authors say, that what happens is that there is a kunstsprache in heroic poetry, as demonstrated by the fact that in the Mocedades de Rodrigo, from the XIV century, the same archaisms are used, with similar epic epithets and formulaic language. As for the author, Pidal first speaks of a poet from Medinaceli with knowledge of San Esteban de Gormaz; then he talks about two poets: the first short verista version by a poet from San Esteban, then a recasting of one from Medinaceli. But Ubieto demonstrated that the local geography of the San Esteban de Gormaz area was unknown to the author, due to great inaccuracies and gaps, for example, not correctly locating the banks of the Duero, and, nevertheless, there is exhaustive knowledge of the place names of the Jalón valley (Cella, Montalbán, Huesa del Común), the area of the province of Teruel. He also locates several exclusive words of Aragonese, which a Castilian author could not know. On the other hand, the Cantar reflects the situation of the Mudejars (with characters such as Abengalbón, Fariz, Galve, even with great loyalty to El Cid), who were necessary to repopulate the Aragonese Extremadura, and therefore, They were very present in the society of southern Aragon, something that did not happen in Burgos. Therefore, according to Ubieto, the author would come from one of those places. It must be remembered that Medinaceli was at that time a disputed place that was sometimes in Aragonese hands. Rafael Lapesa also defended an ancient dating in Spanish Linguistic History Studies , where he tried to show that the composition of the song would date from between 1140 and 1147, but his arguments in this regard are very flimsy.

Colin Smith, as stated, considered Per Abbat the author of the work. He also thinks that the text in the National Library would be a copy of Per Abbat's. For this author, 1207 would be the actual date of composition, and he related Per Abbat to a notary of the time of the same name, who he assumed was a great connoisseur of French epic poetry, and who would be the one who composed the Cantar inaugurating the Spanish epic, making use of his readings and the chansons de geste, and showing his legal training. According to Smith, both the formulary system of the Song and its meter are borrowed from the French epic. However, although there is no doubt that the French epic cycles influence Spanish literature —as shown by the fact that characters such as Roldán, Oliveros, Durandarte or Berta the one with the big feet appear in it— the enormous differences in terms of wonderful elements, exaggeration of the hero's deeds and less realism mean that the Song could be written by any educated writer of the time, without the need for a close French model. In any case, his profound erudition put the most accredited researchers on date and authorship on the track of the current dating of the late XII or early XIII centuries. In addition, Colin Smith himself modified his initial thesis in his later writings, acknowledging that Per Abbat could only be the copyist and that the Cantar was not the starting point of the Spanish medieval epic; the date of composition would also place it in the years prior to 1207; he would maintain, however, the educated and literate authorship for the poem. All these questions have been discussed at length by Alan Deyermond, Antonio Ubieto Arteta, María Eugenia Lacarra, Colin Smith, Jules Horrent and Alberto Montaner Frutos, who took it upon himself to synthesize all the proposals in his edition of Cantar.

Thus, a whole series of historical and social circumstances currently lead researchers to the conclusion that there is a single author, who composed the Cantar de mio Cid between the end of the century 12th and early 13th century, (from 1195 to 1207) who could know the area surrounding Burgos, the Alcarria and the Jalón Valley, cultured, and with deep legal knowledge, possibly a notary or lawyer.

The characters

The main characters in the work are all real, such as Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, Alfonso VI, Diego and Fernando González (infants of Carrión), García Ordóñez, Yúsuf ibn Tašufín or Minaya Álvar Fáñez (conqueror of Toledo and historically a hero almost as great as the Cid himself), as well as many secondaries (Jimena Díaz, cousin of Alfonso VI), Count Don Remont (Berenguer Ramón II), the "moor of peace" Abengalbón, Bishop Don Jerome (Jerónimo de Perigord), Muño Gustioz, Diego Téllez, Martín Muñoz, Álvar Salvadórez, Galín García, Asur González, Gonzalo Ansúrez, Álvar Díaz...); It is not known if they are real or fictitious about others (But Bermúdez, Martín Antolínez, Félez Muñoz, Raquel -who would actually be Raguel or Roguel- and Vidas...), others are fictitious (the Moors Tamín, Fáriz, Galve) and a few appear with the wrong name (the Cid's daughters, Elvira and Sol, are actually Cristina and María; Sancho, abbot of Cardeña, was actually called Sisebuto; Búcar, King of Morocco, is actually the Almoravid general Sir ben Abu-Beker).

The hero, Rodrigo Díaz, El Cid, is more characterized by his attitudes and personality than by his physique, of which only his large beard stands out ("Oh God, how well bearded he is!" v. 789; "the one with the grown beard", v. 1226; "el Cid with the big beard", v. 2410, etc.) who ties himself with a cord and He promises not to cut himself until he returns to Court as a sign of mourning, and his strength. He is also a skilled warrior, pious, a good father, faithful to the king to the point of humiliation: in his wake ("the weeds of the field he took by his teeth", v. 2022), a friend even of Muslim pagans, because one of his best ("myo amigo natural", v. 1479; "amigo sin fault", v. 1528) is a wealthy Mudejar or Saracen, Abengalbón, who discovers the plot of the Infantes to kill him and steal him through a "rogue Moor" or disguised as a Christian who listens to his conspiracy; however, he forgives them in deference to the Cid, thus showing them where true nobility lies (an episode that inaugurates a long tradition of Maurophilia in Castilian literature).

But what really defines El Cid, as determined by Ramón Menéndez Pidal, is moderation, a characteristic of the Castilian way of being that can only be translated as "serenity", "balance" o "containment": the Cid never loses faith in himself even in the harshest circumstances and a fundamental optimism prevails, rejecting even bad omens at a time when superstition was the norm and much more common than today. His revenge is more legal than violent: he demands Cortes from the King, who convenes them in Burgos, and demands the return of the dowry that he gave to the infants in exchange for the marriage of his daughters; likewise, in order not to stain himself with the vileness of the Infantes, and since the real ones responsible for his dishonor are the captains of his retinues, who have hidden their cowardice from him, he leaves in their hands the resolution of the conflict of honor through the riepto or duel to launder one's own honor as a sign of respect for El Cid. El Cid is not a character invulnerable to feelings, nor is he conceited, like Roldán: he gets emotional and prays when it is appropriate and, when a lion is released, he does not kill it to display his strength as any barbarian knight would do, but respects the lion's nobility and returns him to his place, the cage, because this is the right thing to do and what he should also do: be in his place, demonstrating his restraint as a great knight. The episode, one of the fictitious ones created in the song (along with others such as that of the oak grove of Corpes or the coffers of the Jews, the latter coming from an apologist already included in the Disciplina clericalis by Pedro Alfonso), is parodied in Don Quixote de la Mancha, II, 17 by Miguel de Cervantes when the main character opens a lion's cage and it turns its back on him without paying attention. Furthermore, El Cid is also an honest man who has a bad conscience: he feels uncomfortable when Antolínez deceives the Jews Raquel and Vidas and he tries to calm down thinking that he has been forced to do so; when Álvar Fáñez meets them again in the future, the answer will not be exactly the return of the funds: Álvar Fáñez simply puts them off, something that El Cid, the hero himself, would be incapable of doing.

Despite everything, the characterization of Álvar Fáñez is that of a worthy lieutenant who participates in all the virtues of El Cid (although not precisely that of paying debts, as we have already seen), but there is one that stands out in him: He is a great diplomat, which is why El Cid always chooses him to send his embassies to King Alfonso VI with the gifts that are a proportional part of the booty. Martín Antolínez, "el complido burgalés", that is, "perfect", stands out as a loyal and generous character (he provides food to Rodrigo, impoverished by the king), but he is also the cunning who devises the fraud of the coffers with which Raquel e Vidas swindles the Jews, an episode of which some critics have adduced traces of anti-Semitism. He is equally a great warrior who faces the Infants in the final duels.

But Bermúdez, nephew of the Cid himself and cousin of his daughters, is a stutterer and is characterized as a fiery man, impatient and full of enthusiasm and drive, to the point that, raffled among the captains for the honor of crossing the steel first in battle, he forgets that he has not received this distinction and is the first to do so. The other captains of the Cid's retinues joke about his stuttering calling him "Pero Mudo", but he loses, with a great coup d'état, this lingual restraint when he has to challenge one of the Infantes in a powerful speech in the third song, beginning his address with the first proverb that has been transmitted in Spanish literature: "lengua sin manos, cuemo osas fabrar".

The attention to the smallest details in the characterization is perceived even in the care that is given to minor or episodic characters such as Félez Muñoz, the distantly related page of the Cid who does not hesitate to spoil the poor hat that he has given himself with the miserable part that has corresponded to her for the Valencian booty, filling it with water to help her cousins, harassed and abandoned in the Robledal de Corpes to be eaten by wolves by the infamous Infantes of Carrión. This act defines him as "noble"... although this attitude also underlines the generous blood of El Cid that runs through his veins. Doña Jimena is sketched as a pious mother... and as a proud woman, who has had to endure great shame in her forced confinement in the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña: "You have taken me, oh Cid, from many bad shames: / here I am, sir: your daughters accompany me, / for God and for you they are good and well raised".

On the other hand, the Infantes de Carrión are described with such realism and insight into the motives of vileness that one reaches the chill. The text does not stop short when it mentions that, when they were whipping their wives, they competed to see who gave the best blows, a detail of sadism that truly reflects a creative poet who has penetrated deeply within the same psychopathy of evil, stripping it of all possible justification. The "bad guys" of the poem, unlike those of the French epic, the Ganelon of the Chanson de Roland, for example, absolutely lack nobility and grandeur, or even humanity. But another of the negative characters, the Catalan Count Don Remont, appears very different: he appears as a fatuous and conceited courtier who is ashamed of having been defeated by those & # 34; malcalçados & # 34; of the Castilians, refusing to eat until, pitying more for the pitying that his servants exert on him than for the hunger that the character may suffer, the Cid manages with his condescension to make him compromise on eating.

Editions

- Tomás Antonio Sánchez, "Poema del Cid", in Collection of Castilian poetry prior to the 15th century, vol. I. Madrid, 1779, pp. 220-404.

- Jean Joseph Stanislas Albert Ladies Hinard, Poëme du Cid, texte espagnol accompagné d'une traduction française, des notes, d'un vocabulaire et d'une introductionParis, 1858.

- Florencio Janer, "Cantars del Cid Campeador, known as Poema del Cid", in Library of Spanish Authors... Castilian poets prior to the 15th century... Madrid: Manuel Rivadeneyra, 1864. He critically quotes the text of the manuscript, given by Pedro José Pidal, with that of Tomás Antonio Sánchez and that of Damas Hinard, and adds his to the notes of both.

- Andrés Bello, "Poema del Cid", in Complete Works by Don Andrés Bello, vol. II. Santiago de Chile: Imprenta de Pedro G. Ramírez, 1881, pp. 85-303.

- Ramon Menéndez Pidal, Song of My Cid, vol. III, Madrid, 1911; 2.a ed. en Complete works by Ramón Menéndez Pidal, vol. V, Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1946; 3.a ed. Madrid, 1956.

- Ramon Menéndez Pidal, Poem of My Cid, Madrid: La Lectura, 1911; Madrid: Classic Castellanos, No. 24, 1913; 13.a ed. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1971.

- Ramon Menéndez Pidal, Poema de Mio Cid, Facsimil de la edición paleográficaMadrid, 1961.

- Ian Michael, Poem of my Cid, Madrid: Classic Castalia No. 75, 1976; 2.a ed. 1978.

- Christopher Colin Smith, The Poem of the Cid, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972; Castilian version: Poem of the Cid, Madrid: Chair, 1976, very reprinted.

- Miguel Garci-Gómez, Poem of my Cid, Madrid: CUPSA, 1977.

- María Eugenia Lacarra, Poem of my Cid, Madrid: Taurus, 1982. Use Colin Smith's text and merge his notes, those of Menendez Pidal and those of Ian Michael.

- Jules Horrent, Song of Mio Cid / Chanson of Mon Cid, Ghent: Editions Scientifiques, 1982, 2 vols.

- José Jesús de Bustos Tovar, Poem of my Cid, Madrid: Editorial Alliance, 1983.

- Pedro Manuel Cátedra, Poem of my Cid, Barcelona; Planet, 1985.

- Song of mine Cid. Ed, introd and notes by Alberto Montaner Frutos. Preliminary study by Francisco Rico. Barcelona: Critics, 1993.

- Poem of my Cid. Ed. introd. and notes from Julio Rodríguez Puértolas. Madrid: Akal, 1996.

- Poem of my Cid. Ed, introd and notes by Eukene Lacarra Lanz. Barcelona: Debolsillo, 2002. Cid

- Singing from my Cid. Ed. by Alberto Montaner Frutos. Barcelona: Classic Library of Gutenberg Galaxy/Circle of Readers, 2007.

- Poem of my Cid. Ed, introduce, notes and activities of Eukene Lacarra Lanz. Barcelona: Penguin Classics, 2015.

Modern adaptations

Mexican scholar Alfonso Reyes Ochoa made a modern prose version in 1919; the philologist and poet of the Generation of '27 Pedro Salinas adapted the Cantar to modern Spanish in verse in 1926. Other later rhythmic versions in verse are signed by Luis Guarner (1940), the medievalist Francisco López Estrada (1954), Fray Justo Pérez de Urbel (1955), Matías Martínez Burgos (1955), Camilo José Cela (1959) and Alberto Manent (1968). In prose, apart from the one already mentioned by Alfonso Reyes, there are versions by Ricardo Baeza (1941), by Ángeles Villarta (1948), by Fernando Gutiérrez (1958), by the Mexican Carlos Horacio Magis (1962) and by Enrique Rull (1982).).

Contenido relacionado

Louis de Leon

Rafael Leonidas Trujillo

Mario Benedetti