Silicosis

Silicosis is pneumoconiosis caused by the inhalation of silica particles, understanding pneumoconiosis as the disease caused by a deposit of dust in the lungs with a pathological reaction to it, especially of the fibrous type. It tops the lists of occupational respiratory diseases in developing countries, where severe forms are still seen. The term silicosis was coined by the pulmonologist Achille Visconti (1836-1911) in 1870, although the harmful effect of polluted air on breathing had been known since ancient times. Silicosis is an irreversible fibrotic-pulmonary disease and considered a disabling occupational disease. in many countries. It is a very common disease in miners.

Pathophysiology

Respirable silica particles (smaller than 5 microns) that reach the lung parenchyma and are retained are phagocytosed by macrophages, passing to their lysosomes, but the destructive mechanisms available to them (enzymes, oxidizing radicals) are useless against them. the silica; the macrophage ends up destroyed and releases enzymes and radicals into the environment that promote inflammation and generate more oxidizing radicals and enzymes that are not capable of destroying silica, but are capable of injuring the lung tissue itself, leading to fibrosis. Hence, An inflammatory hypothesis has been proposed as the basis for the pathogenesis of silicosis. Subjects who do not control the inflammatory response well may be at a disadvantage. Immunological and infectious (tuberculosis) factors may be incorporated into the pathogenic process. Silicosis usually appears after 10 to 20 years of exposure to silica, sometimes long after it has ceased, but in the case of very intense exposure it can appear early. Not all exposed workers develop the disease, which suggests the existence of individual predisposing factors, insufficiently known for now.

The elementary lesion is the silicosis nodule with a rounded appearance, with a central fibrous part, sometimes hyalinized, surrounded by concentric layers of collagen and a peripheral zone with macrophages loaded with silica and other cells. The presence of silica on examination with polarized light is characteristic. Simple silicosis produces slight functional alterations without significant clinical repercussions.

Complicated silicosis is characterized by the presence in the lungs of masses with a diameter greater than 1 centimeter called Progressive Massive Fibrosis (PMF) masses that, when retracted, generate bullae in their periphery and distort the bronchi, causing obstruction and airflow limitation., apart from other complications (pneumothorax, aseptic cavitation, cavitation due to tuberculosis, etc). If the masses reach a certain size, they significantly alter the parameters of lung function, both ventilation and gas exchange.

Etiology

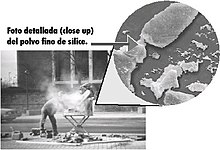

This is nodular fibrosis of the lungs and difficulty breathing caused by prolonged inhalation of chemicals containing crystalline silica. Often fatal, caused by breathing dust containing very small particles of crystalline silica. Exposure to crystalline silica can occur during mining, metallurgy, chemical-related industries, paints, ceramics, marble, stained glass, and less frequently the filter, insulator, polish, piping, heat-insulating, construction, and masonry industries. Activities such as cutting, breaking, crushing, drilling, grinding, or when performing abrasive cleaning of these materials can produce fine silica dust. It can also be on the ground, in the mortar, in the plaster and in the shingles. Very small particles of silica dust can be in the air that you breathe and get trapped in your lungs. The smallest particles and fibers are the most dangerous since they are the ones that can reach the alveoli. It is generally considered that this size below which there is a risk of suffering from silicosis occurs for particles smaller than 5 microns. As dust accumulates in your lungs, they are damaged and it becomes more difficult to breathe as you age.

At the cellular level, exposure to silica dust causes the rupture of lysosomes, which contain numerous enzymes that degrade both internal (deteriorated organelles) and external components (proteins taken up from the outside by endocytosis, for example). These enzymes are deposited in the lungs, causing significant damage to them.

Crystalline silica —silicon dioxide (SiO2)— is what causes silicosis; It is found in nature in the form of quartz, cristobalite or tridymite, quartz being the most abundant (12% of the earth's crust); hence exposure to silica is very frequent. Despite the fact that there are unusual sources of exposure, given its ubiquity, the most important is inland mining, although in some countries exposure in industries related to ornamental stone (granite, slate) is taking a leading role; be alert to industries that generate or use ground silica (silica flour). Exposure to silica that poses a health risk is limited to the work environment and cases of silicosis due to environmental exposure are anecdotal.

Clinical picture

Because chronic silicosis is slow to develop, signs and symptoms may not appear until years after exposure. Signs and symptoms include:

- Disnea, aggravated by effort.

- Tos, often persistent and serious.

- Fatigue.

- Tachypnea.

- Loss of appetite and weight loss.

- Chest pain.

- Fever.

- Gradual darkening of the nails, leading even to its rupture.

In advanced cases, it can also present:

- Cianosis (blue skin).

- Cor pulmonale (right heart failure).

- Respiratory insufficiency.

Classification

There are three types of silicosis:

- Chronic silicosis: It usually occurs after 20 years of contact with low levels of crystalline silica. This is the most common type of silicosis. He looked especially at the miners.

- Accelerated silicosis: It results from contact with higher levels of crystalline silica and occurs 5 to 15 years after contact.

- Acute silicosis: It may occur from 6 months to 2 years of contact with very high levels of crystalline silica. The lungs are quite inflamed and can be filled with fluid causing severe respiratory difficulty and low levels of oxygen in the blood. It has renal, liver and splenic commitment.

There are two clinical forms according to radiology: simple silicosis and complicated silicosis.

Simple silicosis is by far the most frequent clinical form. It shows round (the most frequent) and/or irregular opacities on a simple postero-anterior chest X-ray (Rx). It does not usually produce functional alterations with clinical significance nor does it reduce life expectancy, as long as it does not become complicated.

Complicated silicosis is characterized by the existence of masses of Progressive Massive Fibrosis, also called conglomerate masses, with a diameter greater than 1 cm. It is a serious disease, especially if the masses are large, and the life expectancy of patients is significantly reduced. The evolution from the simple to the complicated form is due to factors that are often unknown. Known factors include: high exposure to silica, abundant nodular profusion, tuberculosis and collagen diseases.

Rarely, the disease may present as diffuse pulmonary fibrosis, interstitial pneumonia, or as a lung mass without apparent background nodulation (silicoma).

Patients with silicosis are particularly susceptible to tuberculosis (TB)—known as silicotuberculosis. The increased risk of incidence is almost 3 times greater than that of the healthy population, without having a certain explanation. Silica-filled macrophages are thought to decrease their ability to kill mycobacteria. Even workers with prolonged silica exposure, but without silicosis, are at increased risk for tuberculosis.

Pulmonary complications of silicosis also include chronic bronchitis and airflow limitation (indistinguishable from that caused by smoking), nontuberculous Mycobacterium infection, pulmonary fungal infection, compensatory emphysema, and pneumothorax. There is some data that reveals an association between silicosis and other autoimmune diseases, such as nephritis, scleroderma, and systemic lupus erythematosus, especially in acute or accelerated silicosis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on a significant employment history and typical X-ray findings. The ILO (International Labor Organization) has developed regulations in order to classify, describe and code radiographic changes attributable to pneumoconiosis and facilitate their comparability in epidemiological studies, without pretensions or legal connotations, although it is also used in the clinic; the 2000 edition is based on the comparison of the patient's Rx with model plates provided by the organization.

Small round opacities are classified according to their diameter as p (the smallest), q (those exceeding 1.5 mm) and r (those exceeding 3 mm and no larger than 10 mm) and irregular ones such as s, t, u depending on their width (equivalent to the diameter in round ones). The quantity or profusion is categorized from 0 to 3.

A combined notation based on profusion is established with 12 categories from 0/- (completely clean lung) 3/+ (the maximum imaginable profusion); for example 1/2 q/t. The first number and the first letter would be the most probable.

The OIT classifies PMF masses) according to their largest diameter as A (exceeding 10 mm), B (exceeding 5 cm alone or added) and C (exceeding an area equivalent to that of the right upper lobe.

In case of diagnostic doubts, High Resolution Computed Tomography (HAT) can be used, which has been shown to be more sensitive and specific for diagnosis. It subjects the patient to much more radiation than Rx and should not be used as a test diagnosis of first level but to clarify doubts. CT allows us to verify how PMF masses frequently originate in the subpleural region of posterior apical areas, progressively displacing the pleura —a sign of detachment—.

Invasive techniques (such as biopsy) should not be indicated for the diagnosis of silicosis unless another entity amenable to treatment is suspected.

Prevention

Primary prevention aims to limit cumulative exposure to silica to prevent disease incidence from exceeding reasonable and acceptable limits. The most widely accepted exposure limit is 0.1 mg/m³ respirable crystalline silica (workday average), proposed by OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration).

The National Silicosis Institute of Spain has developed technical and medical prevention standards. The environmental limit value for daily exposure to silica (VLA-ED) is established for workers in extractive industries at 0.1 mg/m³ (0.05 in the case of cristobalite or tridymite); the respirable fraction of dust will not exceed 3 mg/m³. Primary prevention from the medical point of view is based on examinations prior to work in order to avoid the occurrence of risk factors or lung diseases that could increase the risk. It is necessary to carry out periodic examinations of workers to remove those affected from risk. Having radiological follow-up facilitates diagnosis and avoids certain invasive examinations in doubtful cases (hilar adenopathies due to exposure to silica, incipient PMF, etc.).

The measures to control dust are based on irrigation with water so that the particles settle, use of adequate means that do not re-enter the atmosphere and remove them from the environment with aspiration and ventilation. To the extent that these procedures fail, personal protection measures must be used. Devices can be used to filter and prevent the inhalation of these materials when carrying out work such as mining.

It is important to avoid tobacco, in any case, but especially in workers exposed to silica, and to take the appropriate measures to prevent tuberculosis.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for silicosis, but it is important to remove the source of silica exposure to prevent worsening of the disease. Adjunctive treatment includes antitussives (a drug used to treat irritative dry cough), bronchodilators, and oxygen, if necessary. Antibiotics are prescribed for respiratory infections as necessary. Treatment also includes limiting exposure to irritants, stopping smoking, and having routine skin tests for tuberculosis.

Sociocultural impact

The problem is worrisome because, in addition to causing silicosis, silica seems to be implicated in other diseases and the economic and social repercussions are significant. Severe cases of silicosis continue to be seen. There is sufficient evidence that silica is implicated in lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and pulmonary tuberculosis. Silicosis is considered a public health problem. There are reasons to suspect a relationship with some collagenosis and perhaps with sarcoidosis. Silica attacks a vital organ, putting the patient's life at risk; It is expected that the exhibition will continue in the future due to the expansion of industries related to ornamental stone and the appearance of new industrial uses of silica (abrasive material, silica flour, etc.). Recommended exposure limits are hard to come by and don't seem to protect enough.

Contenido relacionado

Calcaneus

Gland

Epiphysis