Silent movie

The silent film is one in which there is no synchronized sound (especially dialogues) and consists only of images. The silent film era lasted from 1895 to 1929.

The idea of combining images with recorded sound is almost as old as cinematography itself, but until the late 1920s, most movies were silent. This period before the introduction of sound is known as the 'mute era'; or the "silent period". After the premiere of The Jazz Singer (1927), talkies became more and more common and, ten years later, silent films had practically disappeared. The era of silent cinema is often referred to as "The Age of the Silver Screen".

In a September 2013 report, the United States Library of Congress published that 70% of silent films in the United States are believed to be completely lost.

History

The beginnings of silent cinema coincide with the First World War, the first automobiles, the first flight of man. From the thaumatrope in 1825, the zoetrope in 1834, the fixed plate chronophotographer in 1882 (where Kodak took place), the cartoon, to the kinetoscopes in 1894, in March 1895 the cinephotographer was invented, a camera-projector-printer Created by the Lumière brothers. An important discovery that must be highlighted in order to understand depth of field in cinema is Reynaud's invention: his optical theater could be recognized as the first formal animator.

The first silent film was made by Louis Le Prince in 1888. It was a 1.66 second film showing two people walking through a garden and was titled The Roundhay Garden Scene.

The art of cinematography reached its full maturity before the advent of sound motion pictures in the late 1920s. Many scholars maintain that the aesthetic quality of filmmaking declined for several years until directors, agents, and staff of production were adapted to the new talkies. In reality, the visual quality of silent films – especially those produced during the 1920s – was often very good. But there is a very common misconception that these films were primitive and poor quality by modern standards. This misconception is due to the fact that such films had technical errors (such as incorrect playback speed) and to the fact that many of these old films are known from deteriorated copies: many recordings exist only thanks to second or even third generation copies that were made., because the original film was already damaged and neglected.

In small towns there was a piano to accompany the projections, while in big cities there were organs, or even a full orchestra that could play some sound effects.

Features

Silent cinema is one that does not have synchronized sound and consists solely of images, sometimes accompanied by live music. The quality of these films, and especially those of the 1920s, was extremely high.

Sometimes captions or banners were added to clarify the situation for viewers or to show conversations.

It is characterized by not having direct sound, because there had been no technical progress in it. There is a great controversy with this genre since there is no direct sound, however there is music; It is musical, but at the same time it is considered mute.

In the beginnings of silent cinema, the shot that predominates is the long shot due to the weight of the cinematograph.

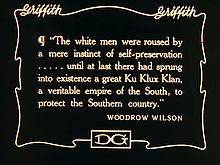

Intertitles

Since silent films could not use picture-synchronous audio to introduce dialogue, text boxes were added to clarify the situation for the audience or to show important conversations where an actual narrative of the dialogue was given. Intertitles (or titles, as they were called at the time) became graphic elements themselves, featuring abstract illustrations and decorations with commentary on the action.

The title writer became a silent film professional, to such an extent that he was often mentioned in the credits as well as the screenwriter.

Live music and sound

Silent cinema used instrumental music typical of romanticism to ensure that this new art was well accepted from its beginnings by the upper and aristocratic classes who listened to that music. Although after 1910 classical and light music alternated.

Music in silent films tried to represent the events that occurred on the screen in an exaggerated and not very subtle way. The pianist or the director decided where these subtleties appeared, and in the best of cases the pianist could see the film to get a better idea of where and how to make them.

Fast rhythms were used for chases, deep sounds for mysterious moments, and romantic melodies for love scenes.

In its beginnings, silent film music consisted of live improvisations performed by a pianist or organist (Jazz music). These improvisations were often on one or two themes. Classical music or theatrical repertoire was also performed.

The theater organ was specially designed to fill the gap between a pianist and an orchestra. The theater organs had a wide range of special effects. The Rudolph Wurlitzer Company organ could simulate orchestral sounds, among others.

Usually small towns had a piano to accompany the projections, but large cities had their own organ or even an orchestra capable of producing sound effects.

The music was collected specifically to accompany the films in the so-called Photoplay Music. This work was carried out by the pianist, the organist, the conductor or the studio itself, who sent a score of the music that was to accompany the film.

Original compositions emerged from the David W. Griffith film Birth of a Nation, and it was common for music to be performed using specially created sheet music. This was an important source of employment for musicians (especially in the United States) until the advent of talkies.

Other ways of offering music to silent films were carried out, for example, in Brazil, where cantatas de fitas were offered: operettas with the singers performing behind the screen. In Japan, live music featured benshi : Live narrator providing the voices of the narrator and characters. The benshi became a mainstay in Japanese films, also serving as a translation for American foreign films.

Incidental Music

Music from this period has hardly been preserved and is very difficult to reconstruct. Compositions can be distinguished into four types: complete reconstructions of compositions already made, composed for the occasion, assembled from already existing music libraries, or improvised again.

Timothy Brock has restored many of Charlie Chaplin's compositions. There are also groups dedicated especially to the accompaniment of silent films, such as the Silent Orchestra, the Alloy Orchestra and the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra.

Interest in compositions for silent films waned in the 1960s and 1970s. A trend emerges in which audiences begin to experiment with purely visual films, without musical distractions. This belief was fueled by the poor quality of some of the silent film compositions.

Today, traditional and contemporary scores for silent films are performed internationally by a large number of soloists, music groups and orchestras.

Why music?

"Without music there wouldn't have been a film industry at all." —Irving Thalberg |

There are several theories that explain the use of music in the origins of cinema:

According to Kurt London, music began to be used to cover up the noise from the projector. Therefore, the piano, organ, orchestra or other groups were incorporated to remedy the constant noise of the mechanism. "Movie theater owners instinctively turned to music and that was the right solution, to use a pleasant sound to neutralize a less pleasant one."

Another theory says that the music served to make the experience of viewing black and white images without any sound more pleasant.

Music was also thought of in a way that would make the viewer believe that they are part of a collective, avoiding their isolation and facilitating their involvement in the scene.

In addition, there are many examples that are often referred to that explain the essential relationship between music and the numerous representations of dramas or religious rites. From Greece, through the liturgical dramas of the Middle Ages, opera and melodramas of the 19th and xx.

These reasons for the relationship between music and cinema, whether artistic, technical or practical, demonstrate that music is an indispensable element of the cinematographic event.

Projection speed

Silent movies were shot on 35mm reels, most silent movies were shot at slower speeds than sound movies (usually 16-20 frames per second vs 24) so unless Special techniques are applied to display them at their original speeds, they can appear artificially fast, adding to their unnatural appearance. However, some silent films–particularly comedies– were intentionally shot slower to speed up the action.

Colour in silent cinema

Between 1895 and 1927, the vast majority of motion pictures were shot in black and white. However, from the beginning many filmmakers tried to give color to the films. Georges Méliès had a team of workers who painted the frames of his films by hand, thus making them appear in color on projection. The most common, however, was another style of color, obtained by dipping segments of film or the entire film in a certain color tint, giving the film a monochrome tone. By the mid-1920s, a whole color code for scene type had developed in the movie industry. Thus, night scenes used to be tinted dark blue or green, while others had other colors. The choice of these colors was so important that, during filming, the clapperboard used to specify, in addition to the take number, the color with which the scene should be tinted in post-production.

The Technicolor company began shooting in natural color in the silent film era, debuting its first rudimentary color process in 1917 with The Gulf Between, the first color film in the United States, of which only a few frames survive. The result was not satisfactory and it would be necessary to wait until 1922 for the process to be perfected and films or fragments of films to continue to be made in color, using the two-color Technicolor process, which used two basic colors instead of three and which, for Therefore, it could not reproduce 100% of the color spectrum. Silent film classics such as The Ten Commandments, The Phantom of the Opera or Ben-Hur contained scenes shot in colour.

The Technicolor process continued to be used during the early years of talkies until, with the onset of the Great Depression, the number of shoots was reduced to a minimum and black and white was again standardized. In the 1940s, the studios got rid of these color films. Technicolor, to make room in its warehouses, destroyed the negatives, so most color film from this period was lost or only black and white copies survive.

Preservation and lost films

In the years before the introduction of sound, many silent films were made, but a considerable number of them (some historians estimate 80-90%) have been lost. Movies of the first half of the 20th century were shot on rolls of celluloid film, which was unstable, highly flammable, and required of careful conservation to prevent it from decomposing over time. Although most of these films were burned or destroyed, many of them have been recycled. Film preservation is a priority among historians.

Later tributes

Several filmmakers have paid homage to the comedies of the silent era. Some of them are Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen with Singing in the Rain (1952), Jacques Tati with M. Hulot's Holidays (1953), Jerry Lewis with The Bellboy (1960), Mel Brooks with La última locura (1976), Maurizio Nichetti with Ratataplan (1979), Tricicle with Palace (1995), Eric Bruno Borgman with The Deserter (2004), Michel Hazanavicius with The Artist (2011) Pablo Berger with Snow White (2012) and Michaël Dudok de Wit with The Red Tortoise.

Contenido relacionado

The Rose

Annex: XIII edition of the Goya Awards

Always (film)