Shamanism

Shamanism refers to a class of traditional beliefs and practices similar to animism. Within those beliefs, shamans draw their power from the forces of nature, including those of animals, to mediate between the ordinary world and the world of spirits, often in altered states of consciousness. They claim to have the ability to control time, prophesy, interpret dreams, use astral projection and travel to the upper and lower worlds. Traditions of shamanism have existed throughout the world since prehistoric times.

Some specialists in anthropology define the shaman as an intermediary between the natural and spiritual worlds, who travels between the worlds in a trance-like state. Once in the spirit world, he communicates with them for help in healing, hunting, or time control. Michael Ripinsky-Naxon describes shamans as "people who have strong ancestry in their surrounding environment and in the society of which they are a part."

A second group of anthropologists dispute the term shamanism, noting that it is a word for a specific cultural institution which, by including any healer from any traditional society, produces a false uniformity between these cultures and creates the misconception of existence of a religion prior to all others. Others accuse them of being incapable of recognizing the commonalities between the various traditional societies.

Shamanism is based on the premise that the visible world is permeated by invisible forces and spirits from parallel dimensions that coexist simultaneously with ours, affecting all manifestations of life. In contrast to animism, which is practiced by each and every member of the society concerned, shamanism requires specialized knowledge or skills. It could be said that shamans are the experts employed by animists or animist communities. However, shamans do not organize themselves into ritual or spiritual associations, such as religion.

Description

There are many varieties of shamanism in the world; the following are beliefs shared by all forms of shamanism: —it must be clarified that shamanism comes from the "shaman", who is typical of the eastern region of Siberia, although, as Mircea Eliade points out in his attempt to make a general history of shamanism, there is a diversity of shamans scattered throughout the world, and they are characterized by the fact that they are doctors and spiritual guides who make "ascents to heaven" -.

- Spirits exist and play an important role both in individual lives and in human society.

- The shaman can communicate with the world of spirits.

- Spirits can be good or bad.

- The shaman can treat diseases caused by evil spirits.

- The shaman can employ techniques to induce trance to incite visionary ecstasy.

- The spirit of the shaman can leave the body to enter the supernatural world to seek answers.

- The shaman evokes images of animals as guides of spirits, omens, and message carriers.

Shamanism is based on the premise that the visible world is dominated by invisible forces or spirits that affect the lives of the living. Unlike organized religions such as animism or animatism which are led by parish priests and practiced by all members of a society, shamanism requires individualized knowledge and special abilities. Shamans operate outside established religions, and traditionally, they act alone. Shamans may join associations, as Indian tantric practitioners have done.

Etymology

The word "shaman" originally referred to the traditional healers of the Turkic and Mongolian areas of north-central Asia (Siberia) and Mongolia. Shaman means 'doctor' in Turco-Tungus ―it literally means 'he who knows'-. Other scholars claim that the word comes directly from the Manchu language. In Turkish they were called kam and sometimes baksı.

The Tungusan word šamán comes from the Chinese sha men taken from the Pali, śamana, and ultimately from the Sanskrit śramana: 'ascetic', which comes from śrama 'fatigue, effort'. The word passed through Russian and German before it was adopted by English, shaman (/sháman/), and found its way into Spanish, where "shaman" (plural, "chamanes") is correct for both masculine and feminine.

Another explanation analyzes the fact that this Tungusan word contains the root sha-, which means 'to know'. The shaman would then be 'the one who knows'.

In common use, it is equivalent to witch, a term that unites the two functions of the shaman: knowledge of magical lore and the ability to heal people and repair a problematic situation. However, the latter term is generally considered pejorative and anthropologically inaccurate. Objections to the use of the word "shaman" They are given because they are a word that comes from a place, from a people, and from a system of specific practices.

The word shaman is in fact used vaguely for almost any wild witch doctor who gets frenzied and has communication with the spirits. In its original form it seems to be a Sanskrit corruption shramana, which indicates a disciple of Buddha and among the Mongols became synonymous with magician.E. Washburn Hopkins

Criticism of the term "shaman"

Certain anthropologists, such as Alicia Kehoe, reject the modern term for its implication of cultural appropriation. They refer to modern Western forms of shamanism, which not only falsify and dilute genuine indigenous practices, but do so in such a way as to reinforce racist ideas, such as that of the noble savage. Another criticism of the term is that it is considered the way in which energy is conducted for the healing of the body, mind and spirit, but that this was an exercise for wise women; and that when the tribes were divided, the knowledge that women had in the spirit realm was ignored and usurped by men. From that moment on, only men were called shamans and women were called witches.

Kehoe is highly critical of the work of Mircea Eliade. Eliade, being a historian rather than an anthropologist, had never done any fieldwork or had direct contact with shamans or cultures that practice shamanism. According to Kehoe, Eliade's shamanism is an invention synthesized from various sources without support from any direct research. She believes that what this and other scholars define as typical of shamanism, trances, chants, communication with spirits, healing, are practices that exist in non-shamanic cultures as well as in some Judeo-Christian rituals. In her opinion, they are typical of various cultures that use them, and cannot be included in a general religion called shamanism. For the same reason, she rejects that shamanism is an ancient surviving religion from the Paleolithic.

Hoppál also disputes whether the term shamanism is appropriate. He recommends using "shamanity" to mark the diversity and specific characteristics of the cultures discussed. This is a term used in old ethnographic reports, both Russian and German, from the early 20th century. He believes that this term is less general and allows local differences to be marked.

Function

Shamans perform a plethora of functions depending on the society where they practice their arts: healing; lead a sacrifice; preserve tradition with stories and songs; clairvoyance; act like a psychopomp In some cultures, a shaman can fulfill several functions in a single person.

The necromancer in Greek mythology can be considered a shaman since the necromancer can gather spirits and raise the dead to use as slaves, soldiers, and instruments for divination.

Mediator

Shamans act as "mediators" in their culture. The shaman is seen as a community communicator with spirits, including the spirits of the dead. In some cultures, this mediating role of the shaman can be well illustrated by some of the shaman's objects and symbols. For example, among the Selkups, one report mentions a sea duck as a spirit-animal: ducks are capable of both flight and diving underwater, thus they are considered to belong to both the upper world and the lower world.

Similarly, the shaman and the jaguar are identified in some Amazonian cultures: the jaguar is able to move freely on land, in the water, and by climbing trees (like the shaman's soul). In some Siberian cultures, it is some species of waterfowl that are related to the shaman in a similar way, and the shaman is believed to take their form.

"The shamanic tree" is an image found in various cultures (Yakuts, Dolgans, Evenkis), Celtic, as a symbol of mediation. The tree is seen as a being whose roots belong to the lower world; its trunk belongs to the middle, world inhabited by humans; and its cup is related to the upper world.

Different types of shaman

In some cultures there may be more types of shamans, performing more specialized functions. For example, among the Nanai people, a different type of shaman acts as a psychopomp. Other specialized shamans can be distinguished according to the type of spirits, or realms of the spirit world, with which the shaman most commonly interacts. These roles vary among Nenets, Enets, and Selkup shamans (article; online). Among the Huichol, there are two categories of shaman. This demonstrates the differences between shamans within the same tribe.

Ecological aspect

In tropical forests, resources for human consumption are easily depleted. In some cultures of the tropical forests, such as the Tucano, there is a sophisticated system for managing resources, and to avoid the depletion of these resources through overexploitation. This system is conceptualized in a mythological context, involving symbolism and, in some cases, the belief that breaking hunting restrictions can cause disease. As the main teacher of tribal symbolism, the shaman can play a leading role in this ecological management, actively restricting hunting and fishing. The shaman is able to "draw" game animals (or their souls) from their hidden abodes.

The Desana shaman has to bargain with a mythological being for the souls of game animals. Not only the Toucans, but also some other tropical forest indigenous people have these ecological concerns related to their shamanism, for example the Piaroa.

In addition to the toucans and piaroa, many Eskimo groups also believe that the shaman is able to bring the spirit of some game animals from remote places; or undertake a journey of the soul to promote luck in the hunt, p. eg asking game animals to mythological beings (Woman of the sea).

Concept of soul and spirits

The plethora of functions described in the previous section may seem like quite different tasks, but some important underlying concepts tie them together.

Concept of soul

In some cases, in some cultures, the concept of soul can further explain seemingly unrelated phenomena:

- Curation

- may be closely based on the concepts of the soul of the belief system of people served by the shaman (on line). It may consist of the recovery of the lost soul of the sick person.

- Few hunting animals

- The souls of the animals of their hidden dwellings can be solved. Apart from this, many taboos may prescribe the behavior of people towards hunting animals, so that the souls of animals do not feel angry or hurt, or the satisfied soul of the already dead preys can tell others, even living animals, that they can be clothed and killed.

The ecological aspect of shamanistic practice (and related beliefs) has already been mentioned earlier in the article.

Infertility in women can be cured by "obtaining" the soul of the child that is expected to be born.

Spirits

Also beliefs related to spirits can explain many different phenomena. For example, the importance of telling stories, or acting like a singer, can be better understood if we examine the entire belief system: a person who is able to memorize texts or long songs (and play an instrument) can be considered as having achieved this ability through contact with spirits (for example among the Khanty people).

Knowledge

Cognitive, semiotic and hermeneutic approaches

As mentioned, one approach (discussed) explains the etymology of the word "shaman" as meaning "one who knows". Indeed, the shaman is adept at holding together the multiple codes through which this complex belief system appears, and holds an overview of it in his mind with certainty of knowledge. The shaman uses (and the public understands) multiple codes. The shaman expresses meaning in many ways: verbally, musically, artistically, and in dance. Meanings can manifest in objects, such as amulets.

The shaman knows the culture of his community well, and acts accordingly. Thus, his audience knows the symbols used and the meanings — this is why shamanism can be efficient: the people in the audience trust it. These belief systems may appear to their members with certainty of knowledge ―this explains the etymology described above for the word "shaman"―.

There are semiotic theoretical approaches to shamanism, ("ethnosemiotics"). The symbols on the shaman's costume and drum may refer to animals (such as helping spirits), or to the rank of the shaman. There were also examples of "mutually opposed symbols", distinguishing "white" shamans practicing by day contacting celestial spirits, and "black" shamans practicing by night contacting evil spirits for evil purposes.

Series of these opposite symbols referred to a vision of the world behind them. Analogous to the way that grammar orders words to express meanings and express a world, this too formed a cognitive map. The shaman tradition is rooted in the folklore of the community, which provides a "mythological mind map". Juha Pentikäinen uses the concept "grammar of the mind". Linking to a Sami example, Kathleen Osgood Dana writes:

Juha Pentikäinen, in his introduction to the shamanism and ecology of the north, explains how the Sami drum embodies the visions of the Sami world. He considers chamanism as a "grammar of mind" (10), because shamans need to be experts in the folklore of their cultures (11)

.

Some approaches refer to hermeneutics, "ethnohermeneutics", coined and introduced by Armin Geertz. The term can be extended: Hoppál includes not only the interpretation of oral or written texts, but that of "visual texts as well (including more complex movements, gestures and rituals, and ceremonies performed for example by shamans)". This may not only reveal the animistic visions behind shamanism, but also express its relevance for the recent world, where ecological problems make paradigms about balance and protection valid.

Ecological approaches, systems theory

Other fieldwork uses systems theory concepts and ecological considerations to understand the shaman tradition. The indigenous Desana and Tucano have developed sophisticated symbolism and concepts of "energy" flowing between people and animals in cyclical pathways. Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff relates these concepts to changes in how modern science (systems theory, ecology, some new approaches in anthropology and archaeology) treats causation in a less linear way. He also suggests a cooperation of modern science and indigenous tradition.

Other remarks

According to Vladimir Basilov and his work Chosen by the spirits, a shaman must be in the best healthy conditions to perform his duties to the fullest. The shaman belief is most popular for people located in Central Asia and Kazakhstan. The traditions of shamanism are also present in the Tajik and Uzbek regions. Shamans' bodies have to be made up of a strong guy, someone having a small build would be pushed aside in no time. Age is a requirement as well, no doubt being over fifty would disqualify those who want to be involved in serving the spirits. Shamans are always of the highest intellect and are looked at from a different perspective, they have a form that makes them quick on their feet and with illnesses they will heal those in need.

One of the most significant and relevant qualities that separate a shaman from other spiritual leaders is their communications with the supernatural world. Already at the beginning of the century, self-hypnosis was highly regarded by those who worshiped. Another characteristic of the shaman is the talent for finding objects and detecting thieves, impressing those of his tribe and those others also around to witness it. The belief in spirits or the supernatural is what attracts those who believe in the shaman. Those who have sick children or are in poor health themselves are what draw them to the spiritual healings of the shaman. Although shamans still exist, the population is undoubtedly declining.

Career

Initiation and learning

In the world's shamanic cultures, the shaman plays the role of priest; however, there is an essential difference between the two, as Joseph Campbell describes:

The pastor is the socially initiated and ceremonially induced member of a recognized religious organization, where he maintains a certain rank and makes a tenant of a position that was occupied by others before him, while the shaman is one, which as a result of a personal psychological crisis, has acquired some power by himself.1969, p. 231

A shaman can be initiated through a serious illness, being struck by lightning and dreaming of thunder to become a Heyoka, or by a near-death experience (eg, Black Elk shaman)., or one can follow a "call" to become a shaman. There is normally a set of cultural imagery that is expected to be experienced during shamanic initiation regardless of the method of induction. According to Mircea Eliade, this imagery often includes being transported to the spirit world and interacting with beings inhabiting the distant spirit world, finding a spirit guide, being eaten by some being and appearing transformed, or being "disassembled" and " "reassembled" again, often with implanted amulets such as magic crystals. Initiation imagery generally speaks of transformation and the powers bestowed to transcend death and rebirth.

In some shamanic societies the powers are considered to be inherited, while in other parts of the world the shaman is considered to have been "called" and requires long training. Among Siberian Chukchi one may behave in ways that "Western" biomedical clinicians would perhaps characterize as psychotic, but which Siberian peoples may interpret as possession by a spirit demanding that one assume the shamanic vocation. Among the South American Tapirapé, shamans are called in their dreams. In other societies the shaman chooses his career. In North America, First Nations peoples would seek communion with spirits through a "vision quest"; while the South American Shuar, seeking the power to defend their family against enemies, teach themselves to become a shaman. Likewise, the Urarina people of the Peruvian Amazon have an elaborate cosmological system based on the ritual consumption of ayahuasca. Along with the millennial impulses, the ayahuasca shamanism of the Urarina is one of the key characteristics of this little-documented society.

Supposedly, common shamanic "traditions" can also be observed among the indigenous Kuna people of Panama, who rely on shamanic powers and sacred talismans for healing. Thus, they enjoy a popular position among the local people.

Shamanic disease

Shamanic illness, also called shamanistic initiation crisis, is a psychospiritual crisis, usually involuntary, or a rite of passage, observed among those who become a shaman. The episode often marks the start of a time-limited episode of confusion or disturbing behavior where the shamanic initiate may sing or dance in an unconventional manner, or experience being "disturbed by spirits." The symptoms are not normally considered signs of mental illness by interpreters of shamanic culture; rather, they are interpreted as introductory telltale signs for the individual who is supposed to take up the role of shaman (Lukoff et. al, 1992). The similarities of some symptoms of shamanic disease to the kundalinī process have often been noted. The significant role of initiation diseases in the calling of a shaman can be found in the detailed history of Chuonnasuan, the last master shaman among the Tungus peoples of northeast China.

Practice

Underlying beliefs of the practice

The shaman plays the role of healer in shamanic societies; Shamans gain knowledge and power by traversing the axis mundi and bringing knowledge from the heavens. Even in western societies, this ancient healing practice is referenced by the use of the caduceus as the symbol of medicine. Often the shaman has, or acquires, one or more familiar helpers in the spirit world; these are often animal spirits, medicinal plant spirits, or (sometimes) those of deceased shamans. In many shamanic societies, magic, magical force, and knowledge are all denoted by one word, such as the Quechua term “yachay”.

Although the causes of illness are considered to be found in the spiritual world, being affected by malicious spirits or witchcraft, both spiritual and physical methods are used to cure. Commonly, a shaman "enters the body" of the patient to deal with the spirit making the patient ill, and heals the patient by banishing the infectious spirit. Many shamans have expert knowledge of plant life in their area, and an herbal regimen is often prescribed as treatment. In many places shamans claim to learn directly from plants, and to be able to harness their effects and healing properties only after obtaining permission from their enduring spirit or patron. In South America, individual spirits are called by singing songs called icaros; before a spirit can be called the spirit must teach the shaman its song. The use of totemic elements such as rocks is common; these items are believed to have special powers and a living spirit. These practices are supposedly very old; around 368 BC C., Plato wrote in Phaedrus that "the first prophecies were the words of an oak tree", and that all who lived at that time found it sufficiently gratifying "to listen to an oak or a stone, while tell the truth."

Belief in witchcraft is prevalent in many shamanic societies. Some societies distinguish shamans who heal from sorcerers who do harm; others believe that all shamans have the power to both heal and kill; that is, in some societies shamans are also thought to be capable of harm. The shaman normally enjoys great power and prestige in the community, and is famous for his powers and knowledge; but they can also be suspected of harming others and are therefore feared.

By engaging in this work, the shaman exposes himself to significant personal risk, from the spirit world, from any enemy shaman, as well as from the means used to change his state of consciousness. Certain used plant materials can be deadly, and failure to return from extracorporeal travel can lead to physical death. Spells are often used to ward off these dangers, and the use of more dangerous plants is very often ritualized.

Methods

Generally, the shaman traverses the axis mundi and enters the spirit world by undergoing a transition of consciousness, entering an ecstatic trance, either self-hypnotically or through the use of entheogens.. The methods used are diverse, and are often used together. Some of the methods to carry out these trances:

- Tobacco (improves concentration, but is not a psychotropic).

- Touch the drum

- Dance

- Song

- Listen to music

- Icaros / Medical Songs

- Vigils

- Fast

- Sudden cabin

- Vision searches

- Mariri

- Struggle with sword / Forging of swords

- "potent" or "masters" plants used as incense or consumed to heal or alter consciousness:

- Psychodelic hooves, euphemistically referred to as "holy children" by the Mazateco shamans like Maria Sabina.[chuckles]required]

- Cannabis

- Cactus of Saint Peter, so called by Saint Peter, keeper and possessor of the keys of the gates of heaven, by the Andean peoples; name in Quechua: huachuma.

- Peyote

- Ayahuasca: in quechua means ‘soga of the dead’; also called I already

- Cebil

- Cedro

- D.

- Belladonna

- We kill

- Iboga

- Glory of the morning

- Sweet cake

- Salvia

- Salvia divinarum (‘savia de los divinadores’)

Shamans often adhere to dietary restrictions or customs particular to their tradition. Sometimes these restrictions are more than just cultural. For example, the diet followed by shamans and apprentices before participating in an ayahuasca ceremony includes foods rich in tryptophan (a biosynthetic precursor of serotonin) as well as avoids foods rich in tyramine, which can induce hypertensive crises if taken with inhibitors. monoamine oxidase as found in ayahuasca concoctions.

Music, songs

Just like shamanism itself, the music and songs associated with it in various cultures are diverse, far from being alike. In some cultures and in several cases, some songs related to shamanism try to imitate natural sounds as well, sometimes through onomatopoeia.

Of course, in various cultures, the imitation of natural sounds may serve other functions, not necessarily related to shamanism: practical purposes such as attracting game animals; or entertainment (katajjaqs of the Eskimos).

Music is one of the oldest arts that connects the human being with his spiritual self because through these vibrations the spirit makes its way in the spiritual world reaching the doors of its own internal god and the spiritual entities who It provides you with strength and wisdom to heal or resolve earthly conflicts.

Music is a very important medium in various spiritualist practices, not just shamanism.

Paraphernalia

As mentioned above, the cultures qualified as shamanic can be very different. Therefore, shamans may have various types of paraphernalia.

Drum

The drum is used by shamans of various Siberian peoples; the same is true of many Eskimo groups, although it may lack shamanic usage among the Eskimos of Canada.

The beating of the drum allows the shaman to achieve an altered state of consciousness or take a journey. The drum is for example referred to as, ""horse" or "rainbow bridge" between the physical and spiritual worlds." The mentioned journey is one where the shaman establishes a connection with one or two of the spirit worlds. With the beating of the drum come neurophysiological effects. Much fascination surrounds the role that the acoustics of the drum play in the shaman. The drums of Siberian shamans are generally constructed of an animal skin stretched over a curved wooden hoop, with a handle across the hoop.

There are two different worlds, the upper and the lower. In the upper world, images such as “climbing a mountain, tree, cliff, rainbow, or ladder; ascend to heaven with smoke; flying on an animal, carpet, or cleaning and finding a teacher or guide", are typically seen. The nether world consists of images including, "entering the earth through a cave, hollowing out a tree stump, puddle, tunnel, or tube". By being able to interact with a different world in an altered, conscious state, the shaman can then exchange information between the world he lives in and the world he has traveled to.

Eagle Feather

These feathers have been seen being used as a type of spirit scalpel.

Rattle

Generally found among South American and African peoples. Also used in ceremonies among the Navajos and traditionally in their blessings and ceremonies.

Nahualism

It is also known that among some of the faculties that the shaman can develop, is that of transforming into some animal form

Gong

Often found among the peoples of Southeast Asia and the Far East.

Didgeridoo and knock knock

Found mainly among the various Aboriginal peoples of Australia.

Gender and sexuality

While some cultures have had a greater number of male shamans, others such as native Korean cultures have had a preference for women. Recent archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest known shamans—dating to the Upper Paleolithic era in what is today the Czech Republic—were women.

In some societies, shamans display a two-spirit identity, adopting the dress, attributes, role or function of the opposite sex, gender fluidity, or same-sex sexual orientation. This practice is common, and is found among the Chukchi, Sea Dayaks, Patagonians, Mapuches, Arapahos, Cheyennes, Navajos, Pawnees, Lakotas, and Utes, as well as many other Native American tribes.. Indeed, these two-spirit shamans were so widespread as to suggest a very ancient origin of the practice. See, for example, Joseph Campbell's map in The Historical Atlas of World Mythology (Volume I: "The Way of the Animal Powers", Part 2: p. 174). These two-spirit shamans are believed to be especially powerful, with shamanism so important to ancestral populations that it may have contributed to the maintenance of the genes of transgender individuals in breeding populations over evolutionary time through the mechanism of "variation selection." kinship". They are highly respected and sought after in their tribes as they will bring high status to their peers.

Duality and bisexuality are also found in the shamans of the Dogon people of Mali (Africa). References to this can be found in various works by Malidoma Somé, a writer who was born and initiated there.

Position

In some cultures, the line between the shaman and the lay person is not clear:

Among the barasana, there is no absolute difference between those men recognized as shamans and those who are not. At the lower level, most adult men have some capacities like shamans and will perform some of the same functions of those men who have a wide reputation for their powers and knowledge.[chuckles]required]

The difference is that the shaman knows more myths and understands their meaning better, but most adult men also know many myths.

Something similar can be observed among some Eskimo peoples. Many lay people have felt experiences that are normally attributed to shamans of these Inuit groups: experiencing waking dreams, daydreaming, or trance are not restricted to shamans. It is the control over the helper spirits that is mainly characteristic of shamans, secular people use amulets, spells, formulas and songs. In Greenland among some Eskimos, there are lay people who may have the ability to have closer relationships with beings of the belief system than others. These people are apprentice shamans who failed to carry out their learning process.

The assistant of an oroqen shaman (called jardalanin, or "second spirit") knows a lot about the associated beliefs: he/she accompanies you in rituals and interprets the behavior of the shaman. Despite this, the jardalanin is not a shaman. Due to his interpretive and accompaniment role, it would even be inappropriate to go into a trance.

The way shamans earn a living and take part in daily life varies between cultures. In many Eskimo groups, they provide services for the community and earn a "due payment" (some cultures believe that payment is given to spirit helpers), but these goods are only "welcome additions". They are not enough to allow shamanism as a full-time activity. Shamans live like any other member of the group, as a hunter or housewife.

History

Shamanism is considered by some as the antecedent of all organized religions, since it was born before the Neolithic, during the Upper Paleolithic. Some indications date from this period in drawings made on the walls of the caves and in furniture objects of art, although there is no conclusive evidence.

Some of its aspects remain in the background of religions, generally in their mystical and symbolic practices. Greek paganism was influenced by shamanism, as reflected in the stories of Tantalus, Prometheus, Medea, and Calypso among others, as well as mysteries, such as those of Eleusis. Some of the shamanic practices of the Greek religion were later copied by the Roman religion.

Shamanic practices in many cultures were marginalized with the spread of monotheism in Europe and the Middle East. In Europe, it began around the year 400, when the Catholic Church gained primacy over the Greek and Roman religions. The temples were systematically destroyed and their ceremonies prohibited or appropriated. The witch hunt was the latest persecution to end the remnant of European shamanism.

The repression continued with the Catholic influence in the Spanish colonization. In the Caribbean, and Central and South America, Catholic priests followed in the footsteps of the conquistadors and were instrumental in destroying local traditions, denouncing their practitioners as "representatives of the devil" and executing them.[citation needed] In North America, the English Puritans conducted periodic campaigns of attack against indigenous peoples whom they regarded as witches. More recently, attacks against participants in shamanic practices have been carried out by Christian missionaries in Third World countries.[citation needed] A similar story of destruction can be told among Buddhists and shamans, for example, in Mongolia.

Today, shamanism survives mainly among indigenous peoples. Its practice continues in tundras, jungles, deserts, and other rural areas, as well as in cities, towns, suburbs, and villages throughout the world. It is especially widespread in South America, where there is the so-called "mestizo shamanism".

Geographic Variations

Europe

Eurasian

Although shamanism had a long tradition in Europe before the advent of Christian monotheism, it remained an organized and traditional religion only in Mari-El and Udmurtia, two semi-autonomous provinces of Russia whose population was mostly Finnish and Hungarian.

Hungarian Shamanism

Among the Hungarian tribes, the center of religion was the worship of the sacred deer and the heavenly eagle known as Turul. The universe was on a titanic tree, the "tree of life", with the underworld at its roots and the upper world of the gods at the top. Along its trunk and crown were three forests, the forest of gold, the forest of copper and the forest of silver, and this was the corporeal region where human beings lived. At the top of the tree, the Turul eagle sat and watched over the universe; he took care of the souls of those who will be born, who existed in the form of birds, who lived in the treetop.

Those who were shamans were born with physical qualities, such as some deformity or an extra pair of fingers on their hands, which legitimized their divine qualities and allowed them to communicate with the gods. In Hungarian shamanism, rivers, rocks, trees and hills were worshiped, the spirits of the ancestors and a superior god, father of the universe, who was served by a court of minor gods and other spiritual entities.

Shamanism in Europe in the Middle Ages

A remnant of shamanism in Europe could be witchcraft, exercised mainly by women who helped in healing or procured the wishes of their neighbors through herbs and spells. European witchcraft was massively persecuted from the late 15th century century, especially in Germany and Switzerland. They were accused of making a pact with the devil, carrying out covens or sabbats, causing the evil eye, causing all the diseases that occurred, from the plague to the death of children, and therefore being burned alive. The persecution ended in the 18th century, with the advent of the Enlightenment.

Spain

In the Canary Islands (Spain), the Guanche aborigines had a class of priests or shamans called Guadameñes.

Asian

It is still practiced in some areas, although in many other cases shamanism was already in decline at the beginning of the XX century.

Russia

The eastern region of Russia, known as Siberia, is a center of shamanism where many of the people who populate the Urals and Altai have kept these practices alive until modern times. Various ethnographic sources have been collected among its people.

Many groups of reindeer hunters and herders practiced shamanism as a living tradition in modern times as well, especially those who have lived in isolation until recent times such as the Naganasan.

When the People's Republic of China was created in 1949 and the border with Russian Siberia was formally sealed, nomadic groups of Tungus practicing shamanism were confined to Manchuria and Mongolia. The last known shaman of the Oroqen, Chuonnasuan (Meng Jin Fu), died in October 2000.

Korea

Shamanism is still practiced in South Korea, where the role of shaman is performed by women called mudang, while the few males are known as baksoo mudang. Both are usually members of lower classes.

Title may be hereditary or due to natural ability. In contemporary society they are consulted to make decisions such as financial and marital.

The mudang and baksoo mudang use of the Amanita muscaria was a traditional practice believed to have been suppressed since the Choseon dynasty. Another (extremely poisonous) mushroom was renamed the shaman's mushroom, "무당버섯". Korean shamans are also known to use spiders. They maintain the colorful costumes, the dances, the drums and the characteristic ritual weapons.

Other Asian Areas

Central Asia

There is a strong shamanic influence in the Bön religion of central Asia, and in Tibetan Buddhism; Buddhism became popular among Tibetan, Mongolian, and Manchu shamans around the turn of the VIII century. Shamanic ritual forms permeated Tibetan Buddhism, becoming institutionalized as a state religion under the Chinese Yuan and Qing dynasties. A common element between both religions is the achievement of spiritual fulfillment, occasionally achieved by psychedelic substances. In any case, the shamanic culture is still practiced by various ethnic groups in areas of Nepal and northern India, where it is not considered extinct today, and there are even people who fear the curses of the shamans.

Tibet

In Tibet, the Nyingma school in particular, maintained the tantric tradition of marrying their priests, known as Ngakpas (masc.) or Ngakmas/mos (fem.). The Ngakpas was in charge of ridding the villages of demons or diseases, creating protective amulets, performing the appropriate rites, etc. They were despised by the monastic hierarchy, which, as in many conventional religious institutions, wished to preserve their own traditions, sometimes at the expense of others: they depended on the liberality of patrons to help them. This situation often led to a clash between the shamanistic peoples with Ngakpa culture and the more conservative monastic system.

Okinawan

It is also practiced in the Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa), where shamans are known as nuru, and in some other rural areas of Japan.

Japan

Many Japanese still believe that Shinto is the result of the transformation of shamanism into a state religion.

Africa

The development of tribal cults in Africa, as in so many parts of the world, is often ascribed, if not to a sorcerer or shaman of the tribe, to a priestly class that acquires particular development as an institution. In many communities there are priests of different categories and specialties that can be studied in two classic groups:

- The official priests of the community or of the group, attached to the temples and responsible for community worship: the temple has a status of a legal person, very similar to that of the Western countries; it may have possessions, lands and even servitude or slaves that constitute its dependence. Among the official functions of the priests are rites of war and sacrifices offered to martial divinities. The most important mission of the priests radiated, before the white penetration, in the administration of justice. Judicial proceedings are often used in more traditional States, such as ordalies consisting of an ad hoc prepared ponzoan beverage; if the accused bears the evidence, his innocence is proclaimed. As the preparation and dosage of the brood is the task of the priestly body, it is understood that the fate of the accused depends absolutely on it. The judicial ordalies therefore constitute a very important instrument of power in the hands of the priests and sometimes of the chiefs or kings at whose service they are.

- Those who freely exercise their practices, including rainbow, healers, sorcerers, sorcerers and diviners, acting on a particular request: they preferred therapeutics and prophecies, and employ for their treatments a true shaman ritual.

In addition to these shamans, in West Africa there is the figure of the djeli, an itinerant singer and musician bard, who is the repository of oral traditions, and sometimes the only source that keeps historical events. He is a figure that remains in Mali, Gambia, Guinea and Senegal, among the Manden, Fula, Wolof, Peul and Serer peoples, among others.

America

The "shamans" Americans have diverse spiritual beliefs. There never existed a common religion or spiritual system in the Americas, these practices being associated with each ethnic group and its territory. Moreover, in Amazonian shamanism, each ethnic group that uses different shamanic techniques such as the use of entheogens, music and repetitive songs, and prolonged diets and isolation, among other practices, have different cosmogonies associated with the alternate worlds that the Amazons visit. shamans.

Some of these indigenous religions have been grossly falsified by observers and anthropologists, taking on superficial and even totally wrong aspects that were taken as "more authentic" than the accounts of members of those cultures. It contributes to the error when thinking that the American religions are something that existed only in the past, and that the opinions of the native communities can be ignored. Not all indigenous communities have individuals with a specific role of mediating with the spirit world on behalf of their community. Among those with this religious structure, spiritual methods and beliefs may have some similarities, although many of these commonalities are due to relations between nations in the same region or because post-colonial government policies mixed independent nations on the same reservations.. This can give the impression that there is more uniformity between beliefs than actually existed in ancient times.

Mapuche

Among the Mapuche people of South America, a man or woman, called machi, serves the community as a shaman; which performs ceremonies and prepares herbs to cure diseases, expel demons and influence the weather and the harvest.

Aimara

The Aymara ethnic group has as part of the community the Yatiris who are the doctors and healers of the community among the Aymaras of Bolivia, Chile and Peru, who use in their practice both symbols and materials such as leaves of Coke. His cures are not only restricted to the human body, but above all to the "soul"; or the one they call AJAYU.

Guarani

In the vast territory shared by Argentina (northeast), Brazil (Paraná State) and Paraguay (east), near the confluence of the Iguazú and Paraná rivers, inhabit the mbyá (men of the mountains or jungle), that they are a Guarani ethnic group. Its shaman-doctors are called caraí opy'guá (lord of the op'y or ceremonial enclosure). They are advanced physical and spiritual healers. Their healing rituals are sometimes massive with the confluence of shamans from many regional communities.

Amazon

In the Colombian, Ecuadorian, Peruvian and Bolivian Amazon, different ethnic groups use entheogenic plants such as ayahuasca, yopo, tobacco and coca in shamanic rituals within their traditional medicine practices. In this sense, the Government of Peru declared ayahuasca as Cultural Heritage of the Nation in 2008 in the category of Knowledge, knowledge and practices associated with traditional medicine. Today, peoples such as the Shipibo-conibo are a reference for the shamanic use of the vine of ayahuasca in combination with the chacruna bush.

Navajo

Navajo "medicine men," known as hatalii, use various methods to diagnose a patient's ailments. They use special tools such as crystalline rocks, and abilities such as trances, sometimes accompanied by chants. The hatalii selects a specific chant for each type of ailment. Navajo healers have to be able to perform the ceremony correctly from start to finish, otherwise it will not work. The training of a hatalii is long and difficult, almost like a priesthood. The apprentice learns by watching his teacher, memorizing the words of all the songs. Sometimes a medicine man cannot learn all the traditional ceremonies, so he may choose to specialize in a few.

Mexico

In Mexico, the survival of magical-religious elements and rituals of the ancient indigenous groups is relevant, not only in the current indigenous but also in the mestizos and whites that make up rural and urban Mexican society. In rural areas the o The are very important for the life of the rural community to the extent that these people can in a certain way direct the life of the people, in a very discreet way they go to them and it is very difficult for these people to accept that they visit a shaman, however, they do it very frequently following all their rituals, although there are many charlatans, there are also many people dedicated to healing the body, soul and spirit, those who truly know the knowledge of our ancestors in herbalism and others if they are able to heal and improve people's lives.

North Peruvian Coast and Sierra

Today, the shamanic tradition is kept alive on the coast and northern highlands of Peru, incorporating ancestral, colonial, and contemporary elements. The San Pedro cactus containing the alkaloid mescaline is a central element in this tradition. Ritual specialists, Andean and mestizo, from the northern healing table in Cajamarca, La Libertad, Lambayeque and Piura use prayers, songs and music to enter a trance for diagnosis and treatment of some illnesses. These practices have been studied by anthropologists such as Douglas Sharon, Luis Millones Santagadea and Alfredo Menacho, among others. On November 14, 2022, the Ministry of Culture of Peru declared knowledge, knowledge, Traditional knowledge and uses of the San Pedro cactus in the practices of quackery in northern Peru.

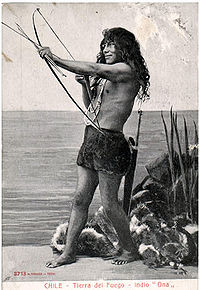

Land of Fire

In the legends of Tierra del Fuego, the xon has supernatural abilities, for example it can control the weather.

Practice

In shamanic cultures, sorcerers play a role similar to that of priests, albeit with one essential difference:

The priest is the social member initiated, ceremonially installed in a recognized religious organization, where he performs certain functions as the manager of an office that was handled by others before him, while the shaman recognized as a result of a personal psychological crisis, because he has gained some ascendant among his own.Joseph Campbell.

A shaman can be initiated because of a serious illness, because he has dreamed of lightning or thunder, or because of a near-death experience, or because he feels called to be. There is a wealth of cultural imagery to experience at initiation, regardless of the method of induction. According to Mircea Eliade, such images often include journeying into the spirit world and learning about the beings that inhabit it, finding a spirit guide, only to emerge transformed, sometimes with amulets implanted, such as magic crystals. Initiation images generally speak of transformation and the powers granted to overcome death and be reborn.

In some societies shamanic powers are considered to be hereditary, while in others they must be "called" and they need a long training. Among the Siberian Chukchis one can behave in such a way that a "Western" Perhaps it would be characterized as a psychopath, but which the Siberians interpret as proof of possession by a spirit, which requires the possessed person to assume his vocation as a shaman. Among the South American Tapirapes, shamans are called in their dreams. In other societies they freely choose their career. In North America, they seek communion with the spirits through a vision, while the South American Shuar seeks the power to defend his family against enemies by learning from other shamans. The urarina from the Peruvian Amazon has an elaborate system, affirmed in the ritual consumption of ayahuasca. Along with millennial impulses, the ayahuasca shamanism of the Urarinas is a dominant feature of this poorly documented society.

Such supposed shamanic traditions can also be seen among the Kuna Indians of Panama, who rely on sacred powers and talismans for healing. Shamans enjoy a privileged position among the local people.

Evil Shamanic

The shaman's illness, also called shamanic initiation crisis, is a psycho-spiritual crisis, or a rite of passage, observed among novice shamans. It often marks the beginning of a short episode of confusion or behavioral disturbances in which the initiate may sing or dance in an unconventional manner, or have an experience of "being bothered by spirits." The symptoms are not considered as signs of mental illness by the interpreters of the shamanic culture; rather they are interpreted as indications to the individual to take up the office of shaman. The significant role of initiatory diseases can be found in the detailed history of Chuonnasuan, the last shaman of the Tungus in Northeast China.

Neoshamanism

The New Age movement has appropriated some ideas of shamanism, as well as beliefs and practices from Eastern religions and different indigenous cultures. As with other appropriations, the original adherents of these traditions condemn its use, considering it poorly learned, superficially understood, and misapplied.[citation needed]

There is an effort in some occult and esoteric circles to reinvent shamanism in a modern form, building on a system of beliefs and practices synthesized by Michael Harner from various indigenous religions. Harner has faced much criticism for believing that parts of various religions can be taken out of context to form some form of universal shamanic tradition. Some of these neo-shamans also focus on the ritual use of entheogens, as well as chaos magic. They claim that they are based on researched (or imagined) traditions from ancient Europe, where they believe many mystical practices and systems were suppressed by the Christian Church.[citation needed]

Some of these practitioners express a desire to use a system that is based on their own ancient traditions. Some anthropologists have discussed the impact of such neo-shamanism on Native American traditions, as these shamanic practitioners do not call themselves shamans, but use specific names derived from old European traditions; the völva (male) or the seidkona (female) of the sagas are an example.

Movies

- Quantum Men (Carlos Serrano Azcona) Spain 2011

- Other Worlds (Jan Kounen) France 2004

- Bells From the Deep (Werner Herzog) Germany 1993

- Shamans of the Blind Country (Michael Oppitz) Germany 1981

- The Mad Masters (Jean Rouch) France 1955

- Au pays des mages noirs (Jean Rouch) France 1947

Contenido relacionado

Afro-Peruvian dances

Excommunication

Indonesian ethnography