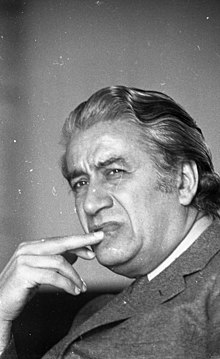

Sergiu Celibidache

Sergiu Celibidache (June 28, 1912, Roman, Romania – August 14, 1996, La Neuville-sur-Essonne, France) was a Romanian conductor who developed his career artistic work mainly in Germany, where he was awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Order of Merit of Bavaria, as well as the Danish Léonie Sonning Music Award. He was an honorary citizen of Munich. His interpretations of the French, German and especially Anton Bruckner repertoire are highly appreciated.

Biography

Of gypsy ethnicity, Sergiu Celibidache was born in Roman, Romania, and began his musical studies on the piano. He later studied music, philosophy and mathematics in Bucharest, Romania and then in Paris. One of the most important influences in his life was Martin Steinke, a scholar of Zen Buddhism, who profoundly affected Celibidache's viewpoint for the rest of his life.

He studied in Berlin and, from 1945 to 1952, was Principal Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. Later he worked with radio orchestras in Stockholm, Stuttgart and Paris. From 1979 until his death he was music director of the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra.

He taught regularly at the University of Mainz in Germany and in 1984 taught at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia (Pennsylvania, USA) and at the Accademia Musicale Chigiana. Teaching had a special emphasis throughout her life and his courses were frequently free to listeners.

Since 1950, he refused to publish a recording of any of his performances, alleging that no recording is capable of capturing all the sound nuances that are perceived live in a concert hall, although, despite everything, he was quite condescending to the circulation of some pirated recordings of their live performances. However, after his death, his family decided to release some of his recordings.

In 1965, Celibidache married Ioana Procopie Dimitrescu, mother of his only son Sergiu Ioan Celibidache ("Serge"), born in 1968, author of the documentary Celibidache's Garden (2010).

Sergiu Celibidache died in La Neuville-sur-Essonne, near Paris in 1996.

Management style

A specialist in interpreting romantic compositions, Celibidache became widely known among music lovers for his peculiar and unmistakable style, closer to the interpretative freedom of Wilhelm Furtwängler than to the firmness and fidelity to the score of Arturo Toscanini, Hermann Scherchen or René Leibowitz. His style, so to speak, can be summed up in two key words: efficiency of gesture and elegance, with his own technique that could be considered the mother of orchestral conducting of the century XX.

His repertoire focuses mainly on romanticism, with a special predilection for the great symphonists such as Beethoven, Bruckner or Tchaikovsky. His style is characterized by great spontaneity, supported by extravagant rehearsal methods, by total freedom in choosing the tempi, which are often much slower than the metronomic indications in the score, and, in addition, due to an enormous subtlety in the timbral nuances, which accentuates the dramatic character of the music.

Philosophy

Celibidache's approach to making music is often described in terms of what not to do rather than what was done. For example, much has been said about Celibidache's "refusal" to make recordings. However, almost all of his concert activities were recorded, and many were publicly released posthumously by major labels such as EMI and Deutsche Grammophon. Even so, he paid little attention to the process of these recordings, which he regarded as mere by-products of his own performances.

Celibidache's interest lay in creating, in each concert, the optimal conditions for what he called a «transcendental experience». He believed that such an experience was hardly comparable to listening to recorded music, which is why he avoided it. As a result, some of his concerts gave audiences exceptional experiences; such is the case of his concert at Carnegie Hall in 1984, considered by the New York Times critic John Rockwell as the best in his twenty-five years of concert attendance.

Since his death, the recordings that exist are now the largest source of access to his art and ideas. These recordings are often considered historical documents, and are often compared to other recordings from the same repertoire but performed by other conductors.

A frequently mentioned characteristic of many of his recordings is, for example, a slower than normal tempo, while, in fast passages, his tempos often exceed the norm. However, from Celibidache's own point of view, criticism of the tempo of the recording is irrelevant, since a criticism cannot be made of the performance but of a transcription of it, which does not recognize the atmosphere of the moment, which for him was the key factor in any musical presentation. As Celibidache explained, the acoustic space in which one listens to the concert directly affects the probability that the desired transcendental experience can emerge. The acoustic space from which one listens to the recording of their performances, on the other hand, has no impact on the performance, in the same way that it is impossible due to the acoustic characteristics of that space to motivate musicians to play, for example, slower or faster. Because of this, the recorded versions of him differ from most other versions.

Notable editions have been his Munich performances of Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner, Schumann, Bach, Fauré, Prokofiev and a series of live concerts with the London Symphony Orchestra.[citation needed]

Disputes

Celibidache's career was not unrelated to controversy. Under his direction, the Munich Philharmonic was involved in a twelve-year legal battle to fire principal trombonist Abbie Conant, which ended in Conant's triumph. Conant alleged sexism in an online article posted by her husband, William Osbourne. The controversy is discussed in Malcolm Gladwell's book Blink.

Partial discography

- 1951: Mozart: Symphony No.25 In G Minor K.183 (Decca LXT 2558)

- 1951: Chaikovski: Symphony No.5 in E Minor, Op.64 LPO (Decca LXT 2545)

- 1969: Chaikovski: Symphony No.5 in E Minor, Op.64 LPO (Eclipse ECM 833)

- 1985: Beethoven: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (Electrecord)

- 1988: Mendelssohn: Symphony N. 4 Italiana; Dvořák: Symphony N. 9 of the New World (Frequenz)

- n.d.: Beethoven: Concerto No.5 for Piano and Orchestra "Emperor" (Electrecord)

- 1990: Chaikovski: Symphony No. 5; Nutcracker Suite (London)

- 1991: Mozart: Réquiem; Vivaldi: Stabat Mater (Arkadia)

- 1991: Chaikovski: Symphony n.o 6 “Pathetique”; Roméo et Juliette (Arkadia)

- 1994: Bruckner: Symphony No. 7 (Andromeda)

- 1994: Brahms: Symphony Nos. 3 & 4 (Fonit-Cetra Italy)

- 1994: Brahms: Symphony n.o 2 " Haydn Variations, Op. 56th (Fonit-Cetra Italy)

- 1994: Mozart: Grand Mass, K. 427 (Cetra)

- 1995: Beethoven: Symphony Nos. 2 fake4 (Nas)

- 1997: Bartók: Concerto for Orchestra (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1997: Beethoven: Symphony Nos. 4 fake5 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1997: Debussy: La Mer; Iberia (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1997: Haydn: Symphony Nos 103 & 104 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1997: Mozart: Symphony n.o 40; Haydn: “Oxford Symphony” (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1997: Ravel: Ma Mère l’Hey; Bolero, Le tombeau de Couperin; Alborada del Gracious (Fonit-Cetra Italy)

- 1997: S. Celibidache Beethoven & Brahms (Tahra)

- 1997: Schubert: Symphony n.o 9 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1997: Schumann: Symphonies 3 &4 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1997: Chaikovski: Romeo and Juliet Fantasy–Overture/Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1997: Chaikovski: Symphony n.o 5 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1997: Chaikovski: Symphony n.o 6 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1997: The Young Celibidache, Vol. II (Tahra)

- 1997: Wagner: Orchestral Music (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1998: Bruckner 3 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1998: Bruckner 4 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1998: Bruckner 6 (EMI Classics)

- 1998: Bruckner 7; Te Deum (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1998: Bruckner 8 (EMI Classics)

- 1998: Bruckner 9 in Concert and Rehearsal (EMI Classics)

- 1998: Bruckner: Mass in F minor (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1998: Bruckner: Symphonies n.o 3-9; Mass in F minor, Te Deum (EMI Classics)

- 1998: Shostakovich: Symphony No. 7 (Magic Talent)

- 1999: Sergei Celebidache (Box) (No Noise)

- 1999: Beethoven: Symphonies n.o 2 & 4 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1999: Beethoven: Symphony n.o 3 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1999: Beethoven: Symphony n.o 6; Leonore (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1999: Brahms: Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1999: Brahms: Symphony n.o 1; Ein deutsches Requiem (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1999: Celibidache Beethoven 7 & 8 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1999: Chaikovski: Symphony No. 2 Op. 17 "Pequeña Russia"; Dvořák: Concerto Op. 104 (Urania)

- 1999: Brahms: Deutsches Requiem (Audiophile Classics)

- 1999: Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition; Stravinsky: The Fairy's Kiss Suite (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 1999: Prokófiev: Scythian Suite; Symphony n.o 5 (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 1999: Rimski-Kórsakov: Sheherazade; Stravinsky: The Firebird Suite (Version 1923) (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 1999: Schumann: Symphony n.o 2; Brahms: Haydn Variations (EMI Music Distribution)

- 1999: Strauss: Don Juan; Tod und Verklärung; Respighi: Pini di Roma (Rehearsals) (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 1999: Chaikovski: Symphony No. 2; Brahms: Symphony No. 4 (Arkadia)

- 2000: Brahms: Symphony No. 2; Mozart: Symphony No. 25 (Urania)

- 2000: Bruckner: Symphonies Nos. 3-5 (Box Set) (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 2000: Bruckner: Symphony No. 3 (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 2000: Bruckner: Symphony No. 4 (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 2000: Bruckner: Symphony No. 5 (Rehearsal) (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 2000: Bruckner: Symphony No. 5; Mozart: Symphony No. 35 (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 2000: Franck: Symphony in D; Hindemith: Mathis der Mahler (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 2000: Richard Strauss: Till Eulenspiegel; Don Juan; Shostakovich: Symphony n.o 9 (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 2000: Schubert: Symphony n.o 8 "Unfinished"; Chaikovski: Nutcracker Suite (Aura Classics)

- 2000: Sibelius: Symphonies Nos. 2 " 5 (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 2001: Sergiu Celibidache (Classica d'Oro)

- 2001: Sergiu Celibidache et la Philharmonie de Berlin (Tahra)

- 2001: Shostakovich: Symphony n.o 7 "Leningrad" (Classica d'Oro)

- 2002: Prokófiev: Symphonies Nos. 1 " 5; Violin Concerto n.o 1 (Classica d'Oro)

- 2003: Mendelssohn: Symphony n.o 4 "Italian"; Bizet: Symphony in C (Archipel)

- 2004: Bach: Mass in B minor (EMI Classics)

- 2004: Bruckner: Symphonies Nos. 3–5, 7–9 [Box Set] (Deutsche Grammophon)

- 2004: Celibidache Conducts Milhaud & Rousel (EMI Music Distribution)

- 2004: Celibidache Plays Mozart's Requiem (EMI Classics)

- 2004: Fauré: Requiem; Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms [Live] (EMI Music Distribution)

- 2004: Overtures by Berlioz; Mendelssohn; Schubert; Smetana & Strauss (EMI Music Distribution)

- 2004: Prokófiev: Symphonies 1 & 5 (EMI Music Distribution)

- 2004: Rimski-Kórsakov: Scheherazade (EMI Music Distribution)

- 2004: Shostakovich: Symphony n.o 7 'Leningrad' (Pickwick)

- 2006: Celibidache: Der Taschengarten (Universal Classics & Jazz)

- 2006: Celibidache: The Complete EMI Edition [Limited Edition] [Box Set] (EMI Classics)

- 2006: Sergiu Celibidache: Lesen & Hören [CD+Book]

- 2007: Beethoven: Symphony n.o 3 "Eroica"; Overture Leonre III (Archipel)

- 2007: Bruckner: Symphony No. 5

- 2007: Schumann: Symphony No. 4; Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition

- 2008: Sergiu Celibedache Conducts Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester (Orpheus)

- n.d.: Prokófiev: Romeo & Juliet (Extracts) (Deutsche Grammophon)

Posts

- Sergiu Celibidache: Über musikalische Phänomenologie. Ein Vortrag und weitere Materialien. Wißner, Augsburg 2008; ISBN 978-3-89639-641-9

- Klaus Weiler: Celibidache – Musiker und Philosoph. Eine Annäherung. Wißner, Augsburg 2008; ISBN 978-3-89639-642-6

- Klaus Umbach: Celibidache – der andere Maestro. Piper, München 1995; ISBN 3-492-03719-4

- Konrad Rufus Müller, Harald Eggebrecht, Wolfgang Schreiber: Sergiu Celibidache. Lübbe, Bergisch-Gladbach 1992; ISBN 3-7857-0650-2

- Annemarie Kleinert: Berliner Philharmoniker von Karajan bis Rattle. Jaron, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-89773-131-2; S. 1-189

- Klaus Lang: „Lieber Herr Celibidache...“ – Wilhelm Furtwängler und sein Statthalter. Ein Philharmonischer Konflikt in der Berliner Nachkriegszeit; M fakeT Edition Musik & Theater, Zürich, 1994, ISBN 3-7265-6016-5

- The Musique n’est rien, Hadrien France-Lanord et Patrick Lang, Ida Haendel, Arlés, Éditions Actes Sud, 336 p. ISBN 978-2-330-00007-3

| Predecessor: Eugen Jochum | Principal Director, Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra 1945-1946 | Successor: Hermann Abendroth |

| Predecessor: Leo Borchard | Musical Director, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra 1945-1952 | Successor: Wilhelm Furtwängler |

| Predecessor: None | Principal Director, Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra 1965-1971 | Successor: Herbert Blomstedt |

| Predecessor: Hans Müller-Kray | Principal Director, Radio Symphony Orchestra of Stuttgart 1971-1977 | Successor: Neville Marriner |

| Predecessor: Jean Martinon | Principal Director, French National Orchestra 1973-1975 | Successor: Lorin Maazel |

| Predecessor: Rudolf Kempe | Director, Philharmonic Orchestra of Munich 1979-1996 | Successor: James Levine |

Contenido relacionado

Nicolas Lancret

Alberto Giacometti

Benaki Museum