Scott Joplin

Scott Joplin (Texarkana, Texas, November 24, 1868-Manhattan, New York, April 1, 1917) was an African-American composer and pianist, one of the most important figures in the development of classic ragtime, for which he wanted a status similar to that of serious music from Europe and the possibility of admitting long compositions such as operas and symphonies.

Joplin was born into a family of blue-collar musicians in Northeast Texas, and developed her musical knowledge with the help of local teachers. He grew up in Texarkana, where he formed a vocal quartet, and taught mandolin and guitar. After traveling through the southern United States, he went to Chicago for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, which played an important role in popularizing ragtime by 1897.

In 1894 he moved to Sedalia (Missouri), where he earned his living as a piano teacher; there he taught future ragtime composers Arthur Marshall, Scott Hayden and Brun Campbell. Joplin began publishing music in 1895, and the publication of the Maple Leaf Rag brought him fame in 1899. In 1901 he moved to Saint Louis, where he continued to compose and publish, performing frequently in that community.. The score of his first opera, An Honored Guest, is confiscated for failing to pay the bills, and is now considered lost. In 1907 he moved to New York to find a producer for a new opera. His second opera, Treemonisha, was not well received in its 1915 partial staging.

In 1916 Joplin suffered from dementia as a result of syphilis. He entered a psychiatric hospital in 1917 where he died three months later, at the age of 48. Joplin's death is widely considered to have marked the end of ragtime as a trend music format, to evolve over the next few years into other styles and become stride, >jazz, and later in Big Band swing.

His music was rediscovered and popular again in the early 1970s, with the release of Joshua Rifkin's million-selling album. This was followed by the 1973 Oscar-winning film The Coup, which featured several of her compositions, most notably The Entertainer. The opera Treemonisha was finally produced in full in 1972. In 1976 Joplin was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize.

Rags

Scott Joplin, unlike other contemporary musicians, had a very solid classical musical training, which materialized in his tendency to obtain a formal balance based on the use of very close tonalities.

His rags use different rhythms and generally include four repeated 16-bar themes, with an introduction and modulation before the third theme; behind the profusion of irregular and arpeggiated sounds, his rags always find a catchy melody that follows the classic antecedent-consequent phrase pattern, thus dividing the eight-bar melody into two interrelated parts. Otherwise, his rags lack development passages.

Scott Joplin never made records, although he did make a few pianola rolls in late 1915 or early 1916; his legacy, therefore, centers almost exclusively on his scores, designed "for millimeter performance and meticulous by the artist".

Early Years

Joplin was born in Linden, Texas, perhaps in late 1867 or early 1868. Although her date of birth was accepted for many years as November 24, 1868, research has revealed that it is almost certainly inaccurate (the The most probable approximate date would be the second half of 1867). He was the second of six children (the others are Monroe, Robert, William, Myrtle, and Ossie) born to Giles Joplin, a former slave from North Carolina, and to Florence Givens., a freeborn black from Kentucky. The Joplins later moved to Texarkana, Texas, where Giles worked as a laborer for the railroad while Florence was a cleaning woman. Joplin's father had played the fiddle for plantation festivals in North Carolina, and her mother sang and played the banjo. Joplin received a rudimentary musical education from her family and at the age of seven was allowed to play the piano. while her mother cleaned.

Sometime in the early 1880s, Giles Joplin left the family for another woman, leaving Florence to support their children with her housework. Biographer Susan Curtis speculated that her mother's support of Joplin's musical education was a major causal factor in their separation. His father argued that this took him away from a practical job that would supplement the family income.

According to a family friend, the young Joplin was serious and ambitious, studying music and playing the piano after leaving school. While some local teachers helped him, he received much of his music education from Julius Weiss, a German-Jewish music teacher who had immigrated to the US from Germany. Weiss had studied music at university in Germany and was listed on city records as Music Teacher. Impressed by Joplin's talent, and realizing the plight of his family, Weiss taught her music for free. He tutored Joplin from the ages of 11 to 16, during which time Weiss introduced her to classical and popular music, including opera. Weiss helped Joplin appreciate music as an "art as well as entertainment," and helped his mother purchase a second-hand piano. According to his wife Lottie, Joplin never forgot Weiss and in his later years, when he rose to fame as a songwriter, sent his former teacher "...gifts of money when he was old and sick", until Weiss died. By the age of 16 Joplin was performing in a vocal quartet with three other boys in and around Texarkana, playing the piano. He also taught guitar and mandolin.

Life in the Southern States and Chicago

In the late 1880s, having performed at various local events as a teenager, Joplin opted to leave work as a railroad clerk and left Texarkana to become a traveling musician. Little is known about his movements in this time, although he is registered in Texarkana in July 1891 as a member of the "Texarkana Troubadours" in a performance to raise funds for a memorial to Jefferson Davis, President of the Southern Confederacy. He soon discovered, however, that there were few opportunities there for black pianists. Churches and brothels were among the few stable job options. Joplin played pre-ragtime jig-piano in various red light districts throughout the Mid-South, and some claim he was in Sedalia, Missouri and St. Louis during this time.

In 1893 Joplin was in Chicago for the World's Fair. During his stay in that city he formed his first band playing the cornet and began with musical arrangements for the group to perform. Although the World's Fair minimized the participation of African Americans, black artists still performed in the bars, cafes, and brothels that surrounded the fair. The expo was attended by 27 million Americans and had a profound effect on many areas of American cultural life, including ragtime. Although specific information is scant, numerous sources have associated the Chicago World's Fair with spreading the popularity of ragtime. Joplin found her music, as well as that of other black artists, to be very popular with visitors. By 1897 ragtime had become a fashion in American cities and was described by the St. Louis Dispatch as "...a true call of nature, which mightily stirred the pulse of the city folk".

Life in Missouri

In 1894 Joplin arrived in Sedalia (Missouri). At first, Joplin stayed with the family of Arthur Marshall, at the time a thirteen-year-old boy, who was later one of Joplin's students and a ragtime composer in his own right. There is no indication that Joplin had a permanent residence in the city until 1904, because until then she led a life as an itinerant musician.

There is little precise evidence known about Joplin's activities at this time, although she performed as a soloist at dances and at the major black clubs in Sedalia, the Negro 400 club and the Maple Leaf Club. He performed in the Queen City Cornet band, and his own six-piece dance band. A tour with his own singing group, the Texas Medley Quartet, gave him his first opportunity to publish his own compositions and he is known to have gone to Syracuse, New York and Texas. Two New York businessmen publish Joplin's first two works, the songs Please Say You Will and A Picture of her Face, in 1895. Joplin's visit Temple, Texas was allowed to have three pieces published there in 1896, including Great Crush Collision March, commemorating a train wreck scheduled as a Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad show on September 15, 1896, who may have witnessed. The march was described by one of Joplin's biographers as a "special...early ragtime rehearsal." While in Sedalia he taught piano to students including future ragtime composers. i> like the aforementioned Arthur Marshall, Brun Campbel, and Scott Hayden. Returning, Joplin enrolled at George R. Smith College, where she apparently studied "...advanced harmony and composition." The university's records were destroyed in a fire in 1925, and his biographer Edward A. Berlin notes that it is unlikely that a small college for African-Americans could offer such a course.

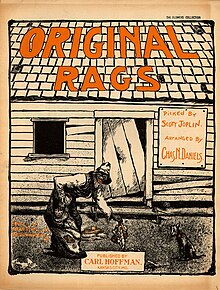

In 1899, Joplin married Belle, the sister-in-law of collaborator Scott Hayden. Although there were hundreds of rags in print by the time the Maple Leaf Rag was published, Joplin was not far behind. His first published rag, Original Rags, had been completed in 1897, the same year as the first printed ragtime work, the Mississippi Rag, by William Krell. Maple Leaf Rag may probably have been known in Sedalia before its publication in 1899; Brun Campbell claims to have seen the manuscript of the work in about 1898. The exact circumstances leading to the publication of the Maple Leaf Rag are unknown, and some accounts of the event contradict each other. After several unsuccessful approaches to publishers, Joplin signed a contract on August 10, 1899, with John Stillwell Stark, a musical instrument retailer who later became his major publisher. The contract stipulated that Joplin would receive a 1% royalty on all sales of the rag, with a minimum retail price of 25 cents. Inscribed "For the Maple Leaf Club" prominently displayed at the top of at least some editions, it is likely that the rag was named after the Club's emblematic maple leaf, although there is no direct evidence to prove the link, and there had been many other possible sources for the name in and around Sedalia at the time.

There have been many claims regarding the sales of the Maple Leaf Rag, for example, that Joplin was the first musician to sell a million copies of a piece of instrumental music. Joplin, Rudi Blesh wrote that during its first six months, the piece sold 75,000 copies, and became "...the first great success of an instrumental work in America". Joplin's later biographer Edward A. Berlin demonstrated that this was not the case; the initial print run of 400 took a year to sell, and under the terms of Joplin's contract with a 1% royalty would have given Joplin a revenue of $4 (or about $130 at current exchange rates). Sales later stabilized, and could have brought Joplin an income that would have covered his expenses. In 1909, estimated sales would have brought him an income of $600 annually (approximately $18,096 at current exchange rates).

The Maple Leaf Rag served as a model for hundreds of rags to come in future compositions, especially in the development of the classic ragtime. After the publication of the Maple Leaf Rag, Joplin was soon described as the King of rag time writers, and by him no less. himself on the covers of his own work, such as The Easy Winners and Elite Syncopations.

After the Joplins moved to St. Louis in the early 1900s, they had a baby girl who died a few months after birth. Joplin's relationship with his wife was difficult because she had no interest in music. They eventually separated and later divorced. Around this time, Joplin collaborated with Scott Hayden on four rags. It was in St. Louis that Joplin produced some of her best-known work, including rags. >The Entertainer (El Animador), March Majestic (March Majestic) and the short play The Ragtime Dance (&# 34;The Rag Dance").

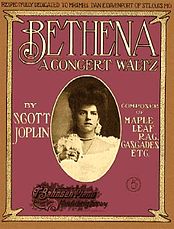

In June 1904, Joplin married Freddie Alexander of Little Rock, Arkansas, the young woman to whom she dedicated The Chrysanthemum. She died on September 10 of that same year from complications resulting from a cold, ten weeks after their wedding. Joplin's first copyrighted work after Freddie's death, Bethena, was described by one biographer as "an enchantingly wonderful piece that ranks among the greatest of ragtime waltzes."

During this time, Joplin created a 30-person opera company and produced her first opera A Guest of Honor for a national tour. It is not certain how many productions were staged, or even if this was an all-black show or a mixed-race production. During the tour, either in Springfield, Illinois, or Pittsburg, Kansas, someone connected to the company stole the proceeds from the box. Joplin would not be able to pay his company's payroll or pay for his lodging at a theatrical lodging house. The sheet music for A Guest of Honor (A Guest of Honor) is believed to have been lost, perhaps destroyed due to non-payment of the guest house bill. the company.

Last years

In 1907, Joplin moved to New York City, which she believed was the best place to find a producer for a new opera. After his move to New York, Joplin met Lottie Stokes, whom he married in 1909. In 1911, unable to find a publisher, Joplin undertook the financial burden of publishing Treemonisha himself. in piano-vocal format. In 1915, as a last-ditch effort to see it performed, he invited a small audience to hear it in a rehearsal room in Harlem. Poorly staged and with only Joplin in piano accompaniment, it was "a miserable failure" for an audience not ready for "raw" so different from European and grand opera of the day. The audience, including potential patrons, were indifferent and walked away. Scott writes that "after a disastrous individual performance... Joplin was disappointed. He was broke, discouraged and exhausted." He concludes that few American artists of his generation faced these obstacles: Treemonisha went unnoticed and uncritically, largely because Joplin had abandoned commercial music in favor of art music, a closed field for African-Americans. In fact, it was not until the 1970s that this opera received a full theatrical staging.

In 1914, Joplin and Lottie self-published their Magnetic Rag as the Scott Joplin Music Company, which had been formed the previous December. Biographer Vera Brodsky Lawrence speculates that Joplin was aware of her advanced deterioration from syphilis and was "...deliberately racing against the clock." In his back cover notes to the 1992 release of Treemonisha by Deutsche Grammophon, he notes that "... plunged feverishly into the task of orchestrating his opera, day and night, with his friend Sam Patterson prepared to copy the parts, page by page, as each page of the full score was completed".

Death

By 1916, Joplin was suffering from the final stages of syphilis and his consequent slide into dementia. In January 1917, he was admitted to Manhattan State Hospital, a mental hospital. He died there on April 1 of dementia. syphilitic, at the age of 48 and is buried in a mass grave that would remain unmarked for 57 years. He was presented with his grave with his name at St. Michael's Cemetery, in East Elmhurs, finally in 1974.

- As a person, he was intelligent, educated and speaking well. And at last quiet, serious and modest. He had few interests besides music. It was not good for trivial conversations, and seldom offered a degree of information; but if a topic interested him, his conversation could be encouraged. He was generous with his time and willing to help and educate younger musicians: he believed deeply in the importance of education

Works

In alphabetical order (in brackets, the year of copyright):

The combination of classical music, the musical environment present around Texarkana—including work songs, gospel, spiritual, and dance music—and Joplin's natural ability has been cited as a significant contribution to inventing a new style that blended African-American musical styles with European forms and melodies, first becoming famous in the 1890s: ragtime.

When Joplin was learning the piano, ragtime was condemned by formal music circles because of its association with vulgar and silly songs "... stamped by the tune makers of Tin Pan Alley." As a composer Joplin refined ragtime, elevating it above the low, rough form played by the "...vagant brothel pianists... who played mere dance music" popular imagination. This new art form, classic rag, combined the syncopation of Afro-descendant popular music and 19th-century European Romanticism, with its harmonic patterns and march-like tempos. In the words of one critic, "ragtime was basically. wrote –no improvisation. Joplin writes her rags as "classical" in a reduced version, in order to elevate ragtime above its "cheap brothel" origins; and create a work that opera historian Elise Kirk described as "...more melodic, counterpoint, catchy and harmonically colorful than any of his time."

Some speculate that Joplin's achievements were influenced by her classically trained German music teacher Julius Weiss, who may have brought an old country polka rhythmic sensibility to the 11-year-old Joplin. As Curtis put it, "the educated German could open the door to a world of learning and music of which the young Joplin was largely unaware."

Joplin's first and most significant hit, the Maple Leaf Rag, was described as the epitome of classic rag, and influenced later rag composers for at least 12 years after its initial publication, thanks to its rhythmic patterns, Melodic lines and harmony, though with the exception of Joseph Lamb, generally failed to amplify it.

Treemonisha

The scene of the opera is a former slave community in an isolated forest near Texarkana, the town of Joplin's childhood, in September 1884. The plot centers on an 18-year-old girl, Treemonisha, who he is taught to read by a white woman, and who then leads his community against the influence of charlatans who prey on ignorance and superstition. Treemonisha is kidnapped and is about to be thrown into a wasp nest when her friend Remus rescues her. The community realizes the value of education and the responsibility of their ignorance to later choose her as their teacher and leader.

Joplin wrote both the score and libretto for the opera, which largely imitates the European type of opera, with many traditional arias, ensembles, and choruses. In addition, themes of superstition and mysticism evident in Treemonisha are common in the operatic tradition, and certain aspects echo forms in the work of the German composer Richard Wagner (of which Joplin was aware). A sacred tree Treemonisha sits under is reminiscent of the tree from which Siegmund draws his enchanted sword in Die Walküre, and the protagonist's origin retelling echoes aspects of the Siegfried opera. In addition, African-American folklore tales influence the story - the hornet's nest incident is similar to the account of Brother Rabbit and Brother Fox and the Bush.

Treemonisha is not a ragtime opera because Joplin employed the styles of ragtime and other black music sparingly, using them to convey a "racial character," and celebrate the music of her childhood in the late 19th century. The opera has been seen as a valuable record of late 19th century black country music recreated by a "skillful and sensitive participant".

Berlin speculates on parallels between the plot and Joplin's own life. He notes that Lottie Joplin (the composer's third wife) saw a connection between Treemonisha's desire to bring her people out of ignorance and a similar desire in the composer. It has also been speculated that Treemonisha represents Freddie, Joplin's second wife, because the date of the opera's development was probably the date of the month of her birth.

At the time of the opera's publication in 1911, the American Musician and Art Journal praised it as "...an entirely new form of operatic art". Critics have since praised the opera as occupying a special place in American history, with its heroine, "...a remarkably early voice for modern civil rights causes, notably the importance of education and knowledge of the African-American rise." Curtis's conclusion is similar: "In the end, Treemonisha offered a celebration of literature, learning, hard work and community solidarity as the best formula for the advancement of the race". Berlin describes it as "...a fine opera, certainly more interesting than many operas being written in the United States," but later notes that Joplin's own libretto showed the composer, "...was not a competent dramatist," with the book it does not reach the quality of the music.

Musician and conductor Rick Benjamin (founder and conductor of the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra) discovered that Joplin managed to perform Treemonisha to an audience in Bayonne, New Jersey, in 1913. On December 6, 2011, the centennial Following the publication of Joplin's piano score, New World Records released an entirely new recording of Treemonisha. In August 1984 Treemonisha premiered in Germany, at the Stadttheater Gießen. In October 2013, stage director Nicolás Isasi directed the premiere of Treemonisha for the first time in Argentina, with a team of 60 young artists, at the Empire Theater in Buenos Aires. Another performance in Germany, falsely labeled as a German premiere, had place on April 25, 2015 at the Staatsschauspiel Dresden under the direction and choreography of Massimo Gerardi.

Performance Skills

Joplin's abilities as a pianist were described in glowing terms by a Sedalia newspaper in 1898, and fellow ragtime composers Arthur Marshall and Joe Jordan said she played the instrument well. However, the son of publisher John Stark claimed that Joplin was a rather mediocre pianist and that he composed on paper, rather than on the piano, Artie Matthews recalled the delight St. Louis musicians took in playing better than Joplin.

As Joplin never made a sound recording, her music is preserved only on seven piano rolls for use on player pianos. All seven were made in 1916. Of these, the six released on the Connorized label show evidence of significant editing, probably by William Axtmann, the arranger on Connorized's staff. Berlin theorizes that by the time Joplin arrived in St. Louis, he may have experienced incoordination of the fingers, tremors, and a slurred speech, clearly all symptoms of the syphilis that claimed his life in 1917. Biographer Blesh described the second roll recording of Maple Leaf Rag for the June 1916 UniRecord label as "...shocking...disorganized and utterly painful to hear." While there is disagreement among pianola roll experts regarding the accuracy of reproduction of what the musician plays, Berlin notes that the Maple Leaf Rag roll was, "painfully bad," and that it would probably be the most faithful record of how Joplin played at that time. The scroll, then, does not reflect the abilities that he may have had earlier in his life.

Legacy

Joplin and her fellow ragtime composers rejuvenated American popular music, stimulating appreciation of African-American music among European-Americans, creating uplifting and liberating dance tunes, changing American taste in music. "Her syncopation and rhythmic drive lent a vitality and freshness appealing to young urban audiences indifferent to Victorian propriety... Joplin's ragtime expressed the intensity and energy of modern urban America."

Joshua Rifkin, an artist noted for his Joplin recordings, wrote: "A pervasive pervasive sense of lyricism infuses his work, and even in its highest spirit, he cannot suppress a hint of melancholy or adversity. "he had very little in common with the fast, flashy school of ragtime that grew up after him." Joplin historian Bill Ryerson adds that "in the hands of a true professional like Joplin, ragtime was a disciplined form capable of amazing variety and subtlety... Joplin did for the rag what Chopin did for the mazurka. His style ranged from tormenting tones to wondrous serenades that incorporated bolero and tango." Biographer Susan Curtis wrote that Joplin's music had helped "revolutionize American music and culture." 3. 4; eliminating Victorian composure.

Composer and actor Max Morath found it striking that the vast majority of Joplin's work did not enjoy the popularity of the Maple Leaf Rag, for while the compositions were of increasing lyrical beauty and syncopal delicacy they were left in the shadows without being heard during his lifetime. Joplin apparently realized that his music was ahead of its time: as historian Ian Whitcomb mentions that Joplin 'opined that the Maple Leaf Rag would make him the 'King of Songwriters' from Ragtime' but that he also knew that he would not be a popular music hero in his own lifetime. "When Ive been dead for twenty-five years, people will recognize me,' he told a friend." Just thirty years later he was recognized, and then the historian Rudi Blesh wrote a great book about ragtime, which he dedicated to Joplin's memory.

Although penniless and disappointed at the end of his life, Joplin set the standard for ragtime compositions and played a key role in the development of the rag. And as a pioneering composer and performer, he helped lead the way for young black artists to reach American audiences of both races. After his death, jazz historian Floyd Levin observed: "Those few who realized his greatness bowed their heads in sorrow. This was the passing of the king of all ragtime writers, the man who gave America authentic native music.

Renaissance

After her death in 1917, Joplin's music and ragtime in general declined in popularity as new forms of musical styles emerged, such as jazz and novelty piano. Even so, jazz bands and artists such as Tommy Dorsey in 1936, Jelly Roll Morton in 1939, and J. Russell Robinson in 1947 re-released recordings of Joplin's compositions. The Maple Leaf Rag was the most frequently found Joplin piece on 78 rpm records.

In the 1960s, a small-scale awakening of interest in classical ragtime was underway among some American music scholars such as Trebor Tichenor, William Bolcom, William Albright, and Rudi Blesh. Audiophile Records released a two-disc set, The Complete Piano Works of Scott Joplin, The Greatest of Ragtime Composers, performed by Knocky Parker, in 1970.

In 1968, Bolcom and Albright interested Joshua Rifkin, a young musicologist, in Joplin's body of work. Together they hosted an occasional night of ragtime and early jazz on WBAI radio. In November 1970, Rifkin released a recording called Scott Joplin: Piano Rags on the classic Nonesuch label, it sold 100,000 copies worldwide. its first year and ultimately became Nonesuch's first million-selling record. of September 28, 1974 has it registered in number 5, with the one that follows it, "Volume 2", in number 4, and the combined of the two volumes in number 3. Separately, both volumes have been on the list for 64 weeks. Topping the top seven on that list, six of the records were recordings of Joplin's works, three of which were by Rifkin. Record labels were first seen putting rag in the classical music section. The album was nominated in 1971 in two Grammy Award categories: Best Album Notes and Best Instrumental Solo Performance (non-orchestra). Rifkin was also considered for a third Grammy for a recording unrelated to Joplin, but at the ceremony on March 14, 1972, Rifkin failed to win in any category. He toured in 1974, which included appearances on the BBC. TV and finished the concert at London's Royal Festival Hall. In 1979 Alan Rich wrote in New York Magazine that by giving artists like Rifkin the opportunity to put Joplin's music on a album Nonesuch Records "...created almost single-handedly, the revival of Scott Joplin.

In January 1971, Harold C. Schonberg, the New York Times music critic, having just heard Rifkin's album, wrote a featured article for the Sunday edition headlined: "Students, Take Care of Scott! Joplin!" Schonberg's call to action has been described as the catalyst for classical music scholars, the kind of people Joplin had battled with all her life, to conclude that Joplin was a genius. Vera Brodsky Lawrence of the New York Public Library published Joplin's work in June 1971 in a joint two-volume titled The Collected Works of Scott Joplin, stimulating broader interest in Joplin's musical interpretation.

In mid-February 1973 under the direction of Gunther Schuller, The New England Conservatory Ragtime Ensemble recorded an album of Joplin's rags, taken from the Standard High-Class Rags period called Joplin: The Red Back Book. The album won a Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance that year, and went on to become Billboard magazine's Best Classical Album of 1974. The group subsequently recorded two more albums for Golden Crest Records: More Scott Joplin Rags in 1974 and The Road From Rags To Jazz in 1975.

In 1973, film producer George Roy Hill contacted Schuller and Rifkin separately, asking each to write the score for a film project he was working on: The Coup (1973 film). Both characters rejected the request due to previous commitments. Instead Hill found Marvin Hamlisch available and brought him to the project as a composer. Hamlisch slightly adapted Joplin's music for The Heist, for which he won an Academy Award for Best Score and Best Musical Adaptation on April 2, 1974. His version of The Entertainer reached number 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 and the American Top 40 chart on May 18, 1974, causing The New York Times write: "The whole nation has begun to understand." Thanks to the film and its score, Joplins work began to be appreciated in both the world of popular and world classical music, favoring (in the words of music magazine Record Word), the "classic phenomenon of the decade". Rifkin later said of the film's soundtrack, that Hamlish took his piano adaptations directly from the style of Rifkin and his Schuller-style band adaptations. Schuller said of Hamlisch,",... got the Oscar for the music he didn't write (because it's by Joplin) and the arrangements he didn't write and the "edits" that he didn't write. which he didn't do. A lot of people were offended by that, but that's 'show business'!

On October 22, 1971, excerpts from Treemonisha were presented in concert at Lincoln Center with musical performances by Bolcom, Rifkin and Mary Lou Williams, supporting a group of singers. Finally, on January 28, 1972, T. J. Anderson's orchestration of Treemonisha was staged in a full opera production for two consecutive nights, sponsored by the African American Music Workshop at Morehouse College in Atlanta, with singers accompanied by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Robert Shaw, and choreography by Katherine Dunham. Schonberg observed in February 1972 that the "Scott Joplin Renaissance" it was in full swing and still growing. In May 1975, Treemonisha was staged in a full opera production by the Houston Grand Opera. The company did a quick tour and then stayed eight straight weeks on Broadway, New York, at the Palace Theater between October and November. These appearances were directed by Gunther Schuller and soprano Carmen Balthrop alternated with Kathleen Battle as the title character. A recording of the 'original Broadway cast' was produced. Due to the lack of national exposure given the brief performance by Morehouse College in 1972, many Joplin scholars wrote that the 1975 Houston Grand Opera performance was the first major production of the work.

1974 saw the Royal Ballet, under the direction of Kenneth MacMillan, create the Elite Syncopations, a ballet based on songs by Joplin and other composers of the day. That year also brought the Los Angeles Ballet's premiere of Red Back Book, choreographed by John Clifford to Joplin rags from the collection of the same name, including both solo piano performances and full orchestra performances and arrangements.

Other awards and recognitions

1970: Joplin has been inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame of the National Academy of Popular Music.

1976: Joplin was awarded a Special Pulitzer Prize,..." awarded posthumously in the nation's Bicentennial Year, for his contribution to American Music.

1977: Motown Productions, produced Scott Joplin, a film biography featuring actor Billy Dee Williams as Joplin, released by Universal Pictures.

1983: The United States Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp of the composer as part of his black heritage.

1989: Joplin received a star in the St. Louis Hall of Fame.

2002: A collection of Joplin's own performances recorded on pianola rolls in the 1900s was listed by the National Recording Preservation Board in the National Library of Congress Recording Registry. The Board annually select songs that are "...culturally, historically or aesthetically significant".

Contenido relacionado

Telesforo (dad)

Edouard manet

Alberto Fujimori