Science fiction

Science fiction is the denomination of one of the genres derived from fiction literature, along with fantastic literature and horror narrative. Some authors consider that the term is a bad translation of English science fiction and that the correct one is scientific fiction. Born as a genre in the 1920s (although there are recognizable works much earlier) and later exported to other media, such as film, cartoons and television, has boomed since the second half of the 20th century due to the popular interest in the future that awoke the spectacular scientific and technological progress achieved during all these years..

It is a speculative genre that recounts possible events developed in an imaginary framework, whose plausibility is narratively based on the fields of physical, natural and social sciences. The action can revolve around a wide range of possibilities (interstellar travel, conquest of space, consequences of a terrestrial or cosmic hecatomb, human evolution due to mutations, evolution of robots, virtual reality, alien civilizations, etc.). This action can take place in a past, present or future time, or even in alternative times outside of known reality, and take place in physical spaces (real or imaginary, terrestrial or extraterrestrial) or the internal space of the mind. The characters are equally diverse: starting from the natural human pattern, he runs through and exploits anthropomorphic models until he ends up creating artificial entities in a human form (robot, android, cyborg) or non-anthropomorphic creatures.

Introduction

Among scholars of the genre, it has not been possible to reach a broad consensus on a formal definition, and this is a subject of great controversy. In general, science fiction is considered to be stories or stories that deal with the impact produced by present or future scientific, technological, social or cultural advances on society or individuals.

Science fiction is a genre of imaginary narratives that cannot occur in the world we know, due to a transformation of the narrative scenario, based on an alteration of scientific, spatial, temporal, social or descriptive coordinates, but in such a way that the related is acceptable as rational speculation.

Science fiction is a type of unrealistic fiction that is not based on supernatural phenomena.

Its name derives from a quite literal translation of the term in English, since the proper translation following the rules of Spanish would be "fiction of/about science" (two nouns, like the original name in English), and some say so. lead to translate "scientific fiction" (noun plus adjective) but this would be "scientific fiction" in English. While many experts believe that the latter, science fiction, should be used, the term is already entrenched in popular culture.

The original term in English is written with a hyphen when it occupies the function of an adjective or a complement. For example: science-fiction novel. For such cases, in English, the abbreviation "sci-fi" can be used if desired. This Anglo-Saxon use of the hyphen has given rise to new linguistic misunderstandings since the hyphen in Spanish brings together nouns where the second modifies the first, that is, unlike in English. Therefore, the use of "science-fiction" in Spanish is not only a misspelling but also distances itself even further from the original meaning in English. In Spanish, the spelling rule of the term «science fiction», always written correctly without a hyphen, is none other than that of the adjective of the second noun, as in the terms «hombre lobo» or «hombre rana», always written without a hyphen. In Spanish, the initials "CF" are also used to refer to the genre.

History of science fiction literature

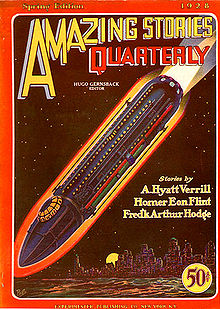

The term «science fiction» was coined in 1926 by Hugo Gernsback when he incorporated it on the cover of one of the best-known speculative narrative magazines of the 1920s in the United States: Amazing Stories. The earliest use of it seems to date from 1851 and is attributed to William Wilson, but this is an isolated use and the term did not become general in its present sense until Gernsback used it consistently (after making a previous attempt to with the term "scientifiction" that did not come to fruition).

It is quite possible that the word "scientific" was used today, but Gernsback was forced to sell his first publication, which had that name. He had inadvertently sold the rights to the term and much to his chagrin he was forced to stop using it and use the term "science fiction" instead.

So, until 1926 science fiction did not exist as such. Until that date, the stories that today we do not hesitate to describe as science fiction received various names, such as "fantastic voyages", "stories of lost worlds", "utopias", or "scientific novels".

The Canadian John Clute calls this period before the emergence of the genre proto science fiction.

Proto-Science Fiction and Early Science Fiction (1818-1937)

Despite the existence of a French proto-science fiction consisting of Le voyageur philosophe dans un pays inconnu aux habitants de la Terre (1761) by Daniel Jost de Villeneuve and The Year 2440 (1771) by the pre-romantic Frenchman Louis-Sébastien Mercier, and even a Spanish one made up of the Static Journey to the Planetary World, 1780, by Lorenzo Hervás y Panduro and the Journey of a philosopher to Selenópolis (1804) by Antonio Marqués y Espejo, for many (for Anglo-Saxons, above all) the first work of science fiction with contents similar to those of the genre, as it is understood today, dates back to 1818, the year Mary Shelley's Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus was published. Although some see elements of science fiction in legends and myths many centuries before. In Greek mythology, Daedalus, the father of Icarus and builder of the Cretan Labyrinth, is said to have built wooden statues that were capable of moving on their own, which may be a primitive idea of the modern concept of robots. And in Jewish folklore the myth of the Golem is also present. Even the trip to the Moon was the subject of literary initiatives before 1818. Lucian of Samosata, II century, in a short novel, True Story, recounts a trip to the Moon in a ship dragged by a providential waterspout. However, the best known early stories of trips to the Moon are that of Cyrano de Bergerac, in the 17th century, and that of the Baron of Münchhausen, 18th century century. However, Carl Sagan and Isaac Asimov agree that Johannes Kepler's Somnium (1634) is the first science fiction story as such. Somnium depicts an adventurer traveling to the Moon and shows Kepler's concern with the issue of what the Earth's motions would look like from the Moon.

There will be some who question the qualification of these works as science fiction (or even proto science fiction). John Clute himself excludes Bergerac's work compared to others who consider Other Worlds to be true science fiction, since despite being written in a comedy tone, it uses the scientific terms of the time. In any case, any of these classic tales inherit much of the spirit of Cartesian rationalism from the XVII that laid the foundations of science modern.

It's hard to set limits. Clute, in his illustrated encyclopedia, doubts the existence of the genre before the end of the 17th century but cites it as a precursor Thomas More; that in his most famous work, Utopia (1516), he describes in narrative form a perfect society residing happily on the island of Utopia.

However, as mentioned above, almost all experts recognize that the work that marked a before and after in the conception of science fiction literature was the work of Shelley.

The first years after the appearance of Frankenstein bore little fruit. Perhaps another of Shelley's works can be highlighted as The Last Man.

In the 1830s, the American Edgar Allan Poe also anticipated the narrative of science fiction (or scientific fiction) in stories such as The incomparable adventure of one Hans Pfaal, The power of Words, Mesmeric Revelation, The Truth About Mr. Valdemar's Case, A Descent into Maelström, Von Kempelen and his discovery, etc. These stories bring together some of the primitive elements of science fiction, such as mesmerism and ballooning —very much in vogue at the time— and cosmological speculation, also present in its visionary essay Eureka, in which black holes and something similar to the Big Crunch seem to be described (op. cit. p. 11).

Later, in the 1850s appears what is probably one of the most prolific authors of the 19th century in the field of scientific adventures: Jules Verne, who in 1863 published his first work with scientific fiction content: Five weeks in a balloon. The appearance of this work is a milestone. From its publication, this genre begins to transform its intentions. The underlying science goes from being a reason for concern or concern about the unknown, to being a support for stories of adventures and discoveries.

Primitive science fiction

Europe

The European branch of science fiction proper began in the late 19th century with the science novels of Jules Verne (1828 -1905), whose science focused more on inventions, as well as the science-oriented novels of social criticism by H. G. Wells (1866-1946). However, although Wells is usually recognized as the great initiator of the genre, Roger Luckhurst shows that he alone was the most influential of a current that began a few years before.

Wells and Verne rivaled each other in early science fiction. Stories and novellas with fantastic themes appeared in periodicals in the last years of the 19th century, and many of them used scientific ideas as an excuse to launch into the imagination. Although he is best known for other works, Arthur Conan Doyle also wrote science fiction. The only book in which Charles Dickens ventured into the territory of scientific speculation and the strange mysteries of nature (as opposed to the clearly supernatural Christmas ghosts) was in his novel Bleak House (1852).) in which one of its characters dies by "spontaneous human combustion". Dickens researched recorded cases of such an effect before writing on the subject in order to be able to answer skeptics who were shocked by his novel.

The next great British science fiction writer after H. G. Wells was John Wyndham (1903-1969). This author liked to refer to science fiction as "logical fantasy." Before World War II Wyndham wrote exclusively for pulp magazines, but after the war he became famous among the general public, well beyond the narrow audience of science fiction fans. Fame came from his novels The day of the triffids (1951), The kraken lurks (1953), The chrysalis (1955) and The Midwich Cuckoos (1957).

Outside the Anglo-Saxon sphere, we must highlight the figure of Karel Čapek, who introduced the term robot in his play R.U.R. and creator of the science fiction classic The War of the Salamanders in 1937.

Spain

Long before H.G. Wells, The Time Machine, saw the light, the writer Enrique Gaspar had already published a novel about time travel. From his imagination was born El Anacronópete , which could be considered the first novel in which a time machine appears as a central element. Published in Barcelona at the beginning of 1887. However, at the end of the XIX century and beginning of the XX, numerous prestigious writers write science fiction stories, novels and plays, such as Miguel de Unamuno, Azorín, Vicente Blasco Ibáñez, Agustín de Foxá, Ramiro de Maeztu or Jardiel Poncela. Many of these stories were published in an anthology by Santiáñez-Tió and unpublished or difficult-to-access texts are even gradually being published.

United States

In the United States of America, the genre can go back to Mark Twain and his novel A Yankee in King Arthur's Court, a novel that explored scientific terms even though they were framed in chivalrous fiction. Through the use of "transmigration of the soul" and the "transposition of ages and bodies" Twain's Yankee is transported back in time and drags with him all the knowledge of the century's technology XIX. The results are catastrophic, as King Arthur's chivalrous aristocracy is perverted by the remarkable power of destruction offered by machines such as machine guns, explosives, and barbed wire.

Another author who wrote some such stories is Jack London. The author of adventure novels in the wild Yukon, Alaska, and the Klondike, he also wrote stories about aliens (The Red One), about the future (The Iron Heel) or about future conflicts (The unprecedented invasion). He also wrote a story about invisibility and another about an energy weapon for which there was no defense. These stories resonated with the American public and began to shape some of the classic themes of science fiction.

But the American author who best symbolizes the birth in the United States of science fiction as a mass genre is Edgar Rice Burroughs who, shortly before the First World War, published Under the Moons of Mars (1912) in several issues of a specialized adventure magazine. Burroughs continued to publish in this medium for the rest of his life, both scientific fantasy and stories from other genres (mystery, horror, fantasy and, of course, his best-known character: Tarzan); but, the stories of John Carter (Mars cycle) and Carson Napier (Venus cycle), which appeared in those pages, are today considered gems of the earliest science fiction.

However, the development of American science fiction as a specific literary genre must be delayed until 1926, the year in which Hugo Gernsback founded Amazing Stories, creating the first magazine dedicated exclusively to science fiction stories. Science fiction. On the other hand, since, as is well known, it was he who chose the term scientifiction to describe this incipient genre, the name of Gernsback and the word to which it gave rise have been linked for posterity. The stories that were published in this and other successful pulp magazines (Weird Tales, Black Mask...), did not enjoy the endorsement of the Serious criticism, which was mostly considered literary sensationalism, however, it was in these magazines, which mixed scientific fantasy with horror in equal parts, where some of the great names in the genre began to shine, such as Howard Phillips Lovecraft, Fritz Leiber, Robert Bloch, Robert E. Howard, etc. All this attracted many readers to the stories of scientific speculation proper.

The Golden Age (1938-1950)

With the appearance in 1938 of the editor John W. Campbell and his activity in the magazine Astounding Science Fiction (founded in 1930) and with the consecration of the new masters of the genre: Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke and Robert A. Heinlein, science fiction began to gain status as a literary genre, especially with the latter, who was the first author to get histories of the genre published in more general publications, and was also the one who gave it greater maturity to the genre and powerfully influenced its subsequent development.

Incursions into the genre by authors who were not exclusively dedicated to science fiction also generated greater respect for it; It is worth mentioning Karel Čapek, Aldous Huxley, C. S. Lewis and in Spanish Adolfo Bioy Casares and Jorge Luis Borges.

After World War II there was a transition of the genre. It is the time in which the stories begin to be displaced by the novels and the arguments gain in complexity. The magazines showed striking covers with fly-eyed monsters and half-naked women, giving an attractive image to what was their main audience: teenagers. New magazines are founded: up to 15 new publications in a single year; and some even cross the Atlantic Ocean like the French Galaxie (first cousin of the American Galaxy that began to be published in 1950), but now the genre is beginning to leave the field exclusive to the pulp.

The Silver Age (1951-1965)

Possibly, what can perhaps be considered the first notable post-war title was not written by an author usually classified as a science fiction writer and, in fact, the book was not even classified as such by its publisher; but it certainly is, and it brought its author worldwide fame; we refer to 1984 (1948) by George Orwell. But the best calling card of the 1950s period is its endless list of writers who have been the backbone of the genre until almost the end of the century: Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, Clifford D. Simak, Arthur C. Clarke, Poul Anderson, Philip K. Dick, Ray Bradbury, Frank Herbert, Stanislav Lem, and many others.

As for the titles, from this period are books that today are considered classics: Martian Chronicles or Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury, Space Merchants by Frederik Pohl and Cyril M. Kornbluth, More Than Human by Theodore Sturgeon; without forgetting The End of Eternity by Isaac Asimov, and Solar Lottery or The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick. Some of them would be adapted to film or television; A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess is a good example of this. It is also at this time that the Hugo Awards begin to be awarded, the first edition of which was in 1953.

In reality, despite the fact that from an academic point of view the period between 1938 and 1950 has been described as the «golden age», for many, this period should last about fifteen years.

Another important novel from this period is Dune (1965) by Frank Herbert.

The New Wave

The years between 1965 and 1972 are the period of greatest literary experimentation in the history of the genre. In the United Kingdom, it can be associated with the arrival of Michael Moorcock as editor of New Worlds magazine. Moorcock, then a 24-year-old, gave space to the new techniques exemplified in the literature of William Burroughs and J.G. Ballard. The themes began to distance themselves from the hackneyed robots and galactic empires of the golden and silver ages of science fiction, focusing on hitherto unexplored topics: consciousness, inner worlds, relativization of moral values, etc.

In the United States, the echoes of the changes experienced in the British scene were reflected. Authors such as Samuel Ray Delany, Judith Merril, Fritz Leiber, Roger Zelazny, Philip K. Dick, Ursula K. LeGuin, Philip José Farmer and Robert Silverberg, represent the essence of the new paths of this literary genre.

Cyberpunk

In the 1980s, increasingly ubiquitous computers and the appearance of the first global computer networks fired the imagination of young authors, convinced that such prodigies would produce profound transformations in society. This germ crystallized mainly through the so-called cyberpunk movement, a term that brought together a pessimistic and disenchanted vision of a future dominated by technology and savage capitalism with a rebellious and subversive “punk” ideology, frequently anarchist. A new generation of writers arose under this label, led by William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, and Neal Stephenson.

Postcyberpunk

A significant shift in science fiction literature occurred in the early 1990s. Authors who were fully cyberpunk before or who had never belonged to that current, began to explicitly reject the clichés of this genre, and incidentally, to consider technology with a more positive vision. It is notorious that this occurred almost at the same time as the accelerated introduction of computers and the Internet into everyday life. As the authors began to really use computers and the global network, their opinions and works began to change and to reject the rebellion and exaltation of the marginality of cyberpunk.

In post-cyberpunk novels, the protagonists are much more often respectable members of their communities: scientists, military, police, and even politicians. Even in the case of more marginal characters, their interest tends to reside in maintaining or improving the status quo, not destroying it, as was typical in cyberpunk; and when they don't, they are often the antagonists.

The first novel to be labeled post-cyberpunk is Snow Crash (1992) by Neal Stephenson. In addition to Stephenson, authors as diverse as Nancy Kress, Greg Egan, Tad Williams, Charles Stross and Richard Morgan have been labeled post-cyberpunk.

Contemporary Subgenres

In recent times, science fiction has been joined by several subgenres whose names also use the postfix "punk." This by analogy with "cyberpunk", which is science fiction focused on cybernetics. These subgenres sometimes respond to stylistic impulses from the authors, or to the demand of readers and viewers, asking for more works with the same style as certain original works. Among these subgenres are:

- Steampunk, or science fiction focused on the anachronistic presence of certain advanced technologies based on, or coexisting with the steam engine, and located during the Industrial Revolution and the Victorian era.

- Biopunk, where fiction focuses on the impact of great advances in biotechnology. It could be placed both in the future, present or in an anachronistic past. Examples of works of this style are the Gattaca film, or the Bioshock video game saga.

- The Retrofuturismo, which retakes in serious or ironic tone, the enthusiasm for the future and the optimistic imagery of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, examples of this genre would be works like Sky Captain and the world of tomorrow.

Science fiction in other media

In magazines

Science fiction is inextricably linked to magazines. The very expression science fiction appeared in one of them. Probably the first periodical magazine with some short stories of this genre (still without an official name) could be considered The Argosy 1896. However, The Argosy was not a magazine exclusively dedicated to to fantastic stories with scientific content. Another early magazine was All Story, which began publication in 1911; it featured most of Edgar R. Burroughs' science fantasy stories.

The two most famous precursor magazines, however, would not arrive until the 1920s; Weird Tales began to be published in 1923 (whose Spanish version was called Terrifying Narratives), and 1926, the year in which Hugo Gernsback coined the term by which the genre for the other of the two "official forerunners": Amazing Stories. Amazing was the first of them all to dedicate itself exclusively to science fiction and had a long history. His early stories were mainly reprints of works by Poe, Wells, and Verne; but previously unpublished accounts by the likes of Burroughs and Merrit were also published. Amazing can be considered the most influential magazine for many years and a point of reference throughout the course of its existence. In 1980, after its last stint under Kim Mohan, the magazine ceased publication, and although various publishers have since attempted to resuscitate it, it can now be considered out of print.

In 1930 another of the classic magazines that all historians include in their list of «golden age» publications arose, Astounding Stories, which would later be republished by John W. Campbell such as Astounding Science Fiction (1938) and which would eventually lead to the current Analog Science Fiction and Fact (1960) and in which the great writers of the genre of those days wrote, including Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, and Poul Anderson. Astounding/Analog (also known by its acronym ASF) is considered a more “scientific” magazine than others, being one of the essential publications from its beginnings to the present.. In 1971, after Campbell's death, Analog was edited by Ben Bova, also known for being the supporter of Orson Scott Card and the one who launched him to fame. Since 1978 it has been edited by Stanley Schmidt.

In 1949 another magazine began to be published that has to its credit the largest series of contributions (in this case, scientific essays) by Isaac Asimov, a total of 399 monthly contributions over 33 years. This is The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. This magazine was first edited by Antony Boucher, and its current editor, Gordon van Gelder, maintains a magazine of high literary quality. Classics such as Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes have been published in its pages.

Another of the magazines that we could not fail to mention is Galaxy (1950). Initially edited by Horace Leonard Gold, it has to its credit the best literary criticism thanks to the public's acceptance of a genre that was beginning to establish itself outside the pulp circles. By looking at the list of authors who published in their first issue, we can get an idea of their quality and drive: Clifford D. Simak, Theodore Sturgeon, Fritz Leiber or Isaac Asimov. This magazine came to be published in Europe (in France and Germany), it had some success for almost thirty years until in 1980 it stopped publishing. In the early 1990s the founder's son resumed publishing Galaxy, but the company eventually ended unsuccessfully in 1995.

Gender is on the rise. New magazines appear every year. Some try to take advantage of the publicity pull of a well-known name to enter a very competitive market. This is, for example, the case of Asimov's Science Fiction which began to be published in 1977 under the direction of Isaac Asimov himself and with George H. Scithers as editor. This fact, however, does not have to diminish the quality of these companies and, for example, the stories published in Asimov's have frequently been awarded Hugo and Nébula prizes.

Also in Spanish, some classic magazines were published, such as the previously mentioned Narraciones. Although there were also purely autochthonous initiatives. Of these, the best known began its life in 1968. It is Nueva Dimensión (ND), founded by Domingo Santos, and was in circulation until 1983, having obtained during those years several international awards. Another magazine, this much more modern, with a certain reputation is Gigamesh, which began to be published in 1991; however, it has never achieved the literary impact of ND. After several publications without periodicity, it has also stopped being published. Also the magazine Galaxia, which under the direction of León Arsenal, obtained in 2003 the prize for the best fantastic literature publication, granted by the European Society of Science Fiction. As we can see, many magazines have suffered a very irregular trajectory, with successive resuscitations and disappearances, a fact that has prevented them from becoming widely known. One of the latter appeared again for a time: Asimov Ciencia Ficción (Spanish version of its American namesake), but it closed definitively after a few years. None of the imports of the famous American magazine in Spain have been successful.

In recent years, the online magazine Scifiworld Magazine has appeared, which is mainly dedicated to the fantastic genre in the audiovisual medium and informs every month about the news of the genre along with articles of various kinds. As of July 2006, the magazine became part of the Sci Fi television network and was renamed scifi.es. Other digital publications have been Revista Exégesis, launched in 2009 and specialized in science fiction comics; and in the short story genre is Axxón (one of the oldest science fiction digital magazines, originating in 1989).

Also in 2006, the A.C. Xatafi begins the digital publication of the magazine Hélice: critical reflections on speculative fiction. Since then he has maintained remarkable regularity with considerable success. This magazine has been the first to propose dignifying the genre in Spain through higher level studies and criticism, between diffusion and academicism, with a professional consideration of the figure of the critic. It won the AEFCFT Ignotus award for the best magazine published in 2007.

In 2008, the A.C. Xatafi published the first digital issue of Artifex, a genre short story magazine that takes over from the paper edition. Its precursor, after going through several formats, has remained for years as the reference for the publication of science fiction stories in Spain.

2008 is also the year in which the printed version of Scifiworld Magazine appears, now independent from the SyFy channel, and which to date has exceeded 40 issues, becoming the longest-running magazine in Spain dedicated to science fiction, fantasy and horror in culture and entertainment.

At the movies

The science fiction genre has been present in the cinema either through the adaptation of stories and novels, or through the production of films with scripts specially created for the screen. Science fiction cinema has been used on occasions to criticize political or social aspects and to explore philosophical issues such as the very definition of the human being.

The genre has been around since the dawn of silent film, when Georges Méliès's A Trip to the Moon (1902) wowed its audiences with its photographic effects. From the 1930s to the 1950s, the genre consisted mostly of low-budget B-movies. Following Stanley Kubrick's landmark 2001: A Space Odyssey from 1968, science fiction cinema was taken more seriously. In the late 1970s, high-budget movies with special effects became popular with audiences. Films like Star Wars or Close Encounters of the Third Kind paved the way for best-sellers in the following decades such as Alien: The Eighth Passenger (1979), E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Blade Runner (1982), Men in Black (1997) and The Fifth element (1997).

On TV

Science fiction first appeared on television during the golden age of science fiction, first in the UK and then in the US. Special effects and other production techniques allow creators to present a living image of an imaginary world that is not limited to reality; this makes television an excellent medium for science fiction, which in turn contributes to its popularity in this way.

Because of its mode of visual presentation, television uses much less exposition than books to explain the underpinnings of the fiction setting. As a result, the definition and boundaries of the genre are less strictly observed than in print media. Because the cost of creating a television show is relatively high compared to the cost of writing and printing books, television shows are bound to attract a much larger audience than print fiction. Some writers and readers believe that a lowest common denominator effect detracts from the quality of science fiction on television, relative to books.

As genre boundaries weaken, writers and viewers must use more inclusive standards than authors and readers, such that in many contexts the category of television science fiction is considered to include all speculative genres, including they the one of fantasy and the one of terror. In the UK, this group is called "telephantasy".

The most famous and enduring examples of work in this field are Doctor Who, Star Trek, Galactica and Stargate, although many other series have attracted audiences large and small for decades.

In the cartoon

The comic strip or science fiction comic is one of the most important genres into which comic production can be divided. The 1970s and 1980s were the heyday of science fiction in this medium, which popularized the genre among millions of readers. The comics offered the most successful scenes of interstellar navigation, moon landings, atomic bombs or hyper-industrialized societies.

In games

Science fiction is also present in many video games and role-playing games.

Awards

Literary

The two most important awards in the genre are the Hugo Awards and the Nebula Awards.

The Hugo Awards, named in memory of science fiction pioneer Hugo Gernsback, are awarded in various categories by the World Society for Science Fiction (WSFS) during the annual Worldcon celebration. During it, the John W. Campbell award for the best new author of the year is also awarded.

The Nebula Awards are also awarded annually in various categories by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association of America (SFWA). This association also grants the coveted Grand Master prizes to the most important writers of the genre for the work of a lifetime.

Some other awards are also named after other notable authors and publishers in the field: the John W. Campbell Memorial (not to be confused with the Best New Author of the same name) and the Clarke, Sturgeon, and Philip K. Dick awards.

Specialized publications also grant some important prizes, such as the American magazine Locus Magazine, which annually awards the Locus prizes.

In Europe, the European Science Fiction Society (ESFS) was created in 1972 and brings together various professionals in the sector. Initially, it scheduled a biannual convention that became annual from 1982, during which the European science fiction awards are awarded, in which the best nominees are: author, translator, promoter, periodical publication, publisher, artist and magazine.

In Spain, there are two grand prizes. The Ignotus awards, granted by the AEFCFT, which are voted for by the partners and by those attending the annual Hispacón national convention. They would be the Spanish equivalents to the Hugos. They have been awarded since 1991 and have various categories. On the other hand, the Xatafi-Cyberdark Award is granted by the A.C. Xatafi and by the Cyberdark virtual bookstore. The winners are chosen by a rotating jury made up of various critics from all over Spain who, over the course of a year, discuss everything published the previous year on a private list. It has been awarded since 2006 and includes the categories of Best Spanish Book, Best Foreign Book, Best Spanish Short Story, Best Foreign Short Story and Best Editorial Initiative in Spain. Since 2012, Scifiworld magazine has also awarded a prize that includes literary and audiovisual works.

Other countries also have their national awards: the Seiun Award in Japan, the British BSFA, the Australian Ditmar, and so on.

Cinematics

In the United States, the Saturns are awarded by the Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Film Academy, being probably the most important awards in the genre.

In Europe, the awards are more related to specific festivals, in which different films are screened. The Sitges Film Festival together with the Brussels International Fantastic Film Festival are the two most important European events of the genre.

In Latin America there are few specialized festivals, one of them is the Buenos Aires Rojo Sangre.

Subgenres

Hard and soft science fiction

This dichotomous classification, literally hard and soft, refers to two opposing tendencies when it comes to developing the scientific approaches on which the work is based.

In the case of hard science fiction, the scientific and technical elements are treated with the utmost rigor, even when they fall within the scope of pure speculation, and the narration is subordinated to this rigor. The hard science fiction film par excellence is 2001: A Space Odyssey. Much of Soviet science fiction falls along these lines.

Barceló (1990) says with reference to hard:

When science fiction takes up the most strictly scientific themes and is based primarily on the world of science, it is spoken of science fiction “dura”, commonly of science fiction hard, using the original English word directly as almost no one uses its literal Spanish translation. Generally, physics, chemistry of biology, with its derivations the field of technology, sciences that support most thematic speculation of hard fiction science.Barceló (1990, p. 55)

Regarding soft science fiction he writes:

In contrast to the scientific-technological basis of the most classical science fiction, the 1960s contemplated [...] attempts to incorporate the social sciences as anthropology, history, sociology and psychology into the sphere of science fiction. [...] Its authors are often characterized by little or no scientific training and an almost exclusive interest for the mere literary. Thanks to this [...] it has incorporated a higher literary quality to science fiction and [...] has provoked an obvious improvement of the genre.Barceló (1990, p. 59)

Obviously the distinction between both aspects is diffuse and we can find works that share both approaches. But, in general, science fiction authors can be included in one category or another.

Main genres

- Shots

- Ucronías

- Counterfactual history

- Cyberpunk

- Postciberpunk

- Military fiction

- Space opera

- Planetary Romance

- Sword and planet

- Space western

- Steampunk

Frequent topics

There are a lot of topics covered in science fiction. Some of them are:

- Possible inventions or future scientific and technical discoveries (fiction technology) and advances in fields such as biotechnology, nanotechnology, bionics, etc.

- Genetic engineering and cloning.

- utopian, dystopian or apocalyptic future.

- Ucrony.

- Time travel.

- Alien life.

- Exploration and colonization of outer space.

- Travel through interstellar space and intergalactic space.

- Artificial and robotic intelligence.

- Computers or computers and computer networks.

- Solipsism.

Contributions of science fiction to science

Just as science fiction has taken many of its plots and setting elements from concepts or creations of science, science has sometimes taken elements of science fiction literature to turn them into real concepts or working hypotheses of science. facing the scientific or technological future.

The best-known cases of this transfer are those of the term robot used for the first time by the Czech writer Karel Čapek -which derives from the word «robota», which in his language means «work hard and heavy'; given that these were understood as specific machines to perform these functions- in his work R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots), the derivative term robotics, created in Isaac Asimov's robot novels, the space elevator, independently imagined by Arthur C. Clarke and Charles Sheffield, or the concept of geostationary orbit, developed by Herman Potočnik and later by Arthur C. Clarke. That is why it is also known as Clarke's orbit.

Other concepts have been profusely developed by science fiction even before being taken into account by science. For example, Jules Verne in From the Earth to the Moon (1865) described how three men are thrown from Florida to the Moon. The Apollo 11 astronauts departed from that same point 100 years later. In The world set free (The world set free, 1914), H.G. Wells predicted nuclear power and the use of the atomic bomb in a future war with Germany. And in the novel Ralph 124C 41+ (1911), Hugo Gernsback described radar in detail before he had been invented. Science fiction has also speculated about antimatter, wormholes, or nanotechnology before science itself.

Some concepts have had a notable influence, despite currently being nothing more than mere figments of the imagination. For example, Asimov's psychohistory has slightly influenced the way we view sociology from a mathematical point of view.

Finally, and surprisingly, some science fiction inventions have inspired some of the current lines of research, such as instantaneous communication (ansible, tachyons).

Terminology

Within science fiction terminology, there are words that are common to regular readers of the genre but not to new readers.

However, they are not created as a form of identifying language, but are more often than not interesting ideas and concepts that have become public domain, within the genre and even outside of it, in the world of The science.

These terms are widely used in science fiction stories and novels. As an example we have hyperspace, which is a kind of "alternative space" through which you can travel from one point to another; societies or hive minds, which are intelligent systems composed of the minds of many beings and not just one, etc.

Additional bibliography

- Aldiss, Brian W.; Wingrove, David (1986). Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction. Atheneum. ISBN 0-689-11839-2.

- Amis, Kingsley (1966). The Universe of Science Fiction. Madrid: Editorial Ciencia Nueva.

- Asimov, Isaac (2005). Full stories I and full stories II. Barcelona: Editions B. ISBN 978-84-666-2181-6, ISBN 978-84-666-2285-1.

- Barceló, Miquel (1990). Science fiction, reading guide. Barcelona: Editions B. ISBN 84-406-1420-9.

- Capanna, Paul (1969). The sense of science fiction. Buenos Aires: Editorial Columba.

- Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter, eds. (1995). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- Csicsery-Ronay Jr., Istvan (2008). The Seven Beauties of Science Fiction. Middletown, CT, Wesleyan University Press.

- Díez, Julián (2008). "Secession." Propeller: Critical reflections on speculative fiction (10): 5-11.

- - (2009). "Analogy." Prospective: Looking to the Future from Fiction.

- Disch, Thomas M. (1998). The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of. Touchstone.

- Ferreras, Juan Ignacio (1972). The science fiction novel. Madrid: CenturyXXI.

- Ferrini, Franco (1971). What is truly science fiction. Madrid: Doncel.

- Gunn, James; Candelaria, Matheew, eds. (2005). Speculations on Speculations: Theories of Science Fiction. Lanham-Toronto-Oxford: Scarecrow Press.

- Hollinger, Veronica; Gordon, Joan, eds. (2002). Edging into the Future: Science Fiction and Contemporary Cultural Transformation. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- James, Edward (2003). The Cambridge companion to science fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01657-6.

- Jameson, Fredric (2009). Future archeologies: Desire called utopia and other approaches to science fiction. Madrid: Akal.

- Kagarlitski, Yuli (1977). What is science fiction?. Barcelona: Editions Guadarrama.

- Ketterer, David (1976). Apocalypse, utopia, science fiction. Apocalyptic imagination, science fiction and American literature. Buenos Aires: Las Paralelas.

- Lecaye, Alexis (1981). Les pirates du paradis: essai sur la science fiction. Paris: Denoël-Gonthier.

- López Pellisa, Teresa; Moreno, Fernando Ángel, eds. (2009). Essays on science fiction and fantastic literature. Madrid: Carlos III University and Xatafi Cultural Association. Archived from the original on 5 June 2012.

- Lorca, Javier (2010). From the spacecraft to the cyborgs. History of science fiction and its relationships with machines. Buenos Aires: Capital Intelectual.

- Luckhurst, Roger (2005). Science Fiction. Cambridge: Polity.

- Lundwall, Sam J. (1976). History of science fiction. Barcelona: Dronte.

- Malmgren, Carl D. (1988). «Towards a Definition of Science Fiction». Science Fiction Studies 15 (46): 259-281.

- Moreno, Fernando Angel (2017). Future study: didactic science fiction. Mexico City: Bonilla Artigas Editores. ISBN 978-607-8450-80-0.

- Moreno, Fernando Angel (2010). Theory of science fiction literature: Poetic and rhetoric of the prospective. Ignotus Award and Scifiworld Award. Vitoria: PortalEditions. ISBN 978-84-937075-7-6.

- - (2007). «Notes for a Story of Science Fiction in Spain». They say. Hispanic Philology Notebooks (27): 125-138. ISSN 0212-2952.

- - (2008). "The rhetorical planning of the science fiction novel." Letters from Deusto 38 (120): 95-106. ISSN 0210-3516.

- — (July-December 2009). "On the fictional nature of science fiction: theoretical contributions to his study." Revista de Literatura Hispanoamericana (59): 65-91. ISSN 0252-9017.

- - "Development of the fictional contract in two subgeners of science fiction: hard and prospective." Interlitteraria (16): 247-268.

- - (2012). Prospectives: Anthology of the current Spanish science fiction story. Madrid: Page Jump. ISBN 978-84-15065-31-9.

- Parrinder, Patrick, ed. (1979). Science Fiction: a Critical Guide. London: Longman.

- Plans, Juan José (1975). Science-fiction literature. RTVE Cultural Library. Madrid: Coedición de Editorial Prensa Española y Editorial Magisterio Español. ISBN 84-287-0347-7.

- Rose, Mark (1981). Alien Encounters: Anatomy of Science Fiction. London: Harvard University Press.

- Saint-Gelais, Richard (1999). L’Empire du pseudo: Modernites de la sciencefiction. Quèbec: Editions Nota Beue.

- VV.AA. (2007). Teacher Works: The Best Science Fiction of the CenturyXX.. Barcelona: Editions B. ISBN 978-84-666-3391-8.

- VV.AA. (2009). The Routledge Company of Science Fiction. London and New York: Routledge.

- Weldes, Jutta, ed. (2003). To Seek Out New Worlds: Science Fiction and Politics. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-29557-X.

Contenido relacionado

Moby Dick (1956 film)

Lilith (film)

Miffy