Scholasticism

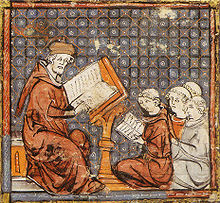

The scholasticism —a word originating from Medieval Latin scholasticus, through Late Latin scholastĭcus «scholar», «scholar» as a loan from the Greek σχολαστικός, scholastikós «leisure, free time»— is a medieval theological and philosophical current that he used part of classical Greco-Roman philosophy to understand the religious revelation of Christianity. It was the predominant theological-philosophical current of medieval thought, after the patristics of Late Antiquity, and it was based on the coordination between faith and reason, which in any case always implied a clear subordination of reason to faith (Philosophia ancilla theologiae, "philosophy is the servant of theology"). José Ferrater Mora points out that "today there is a tendency to reject this conception or not to insist too much on it." Scholasticism “is not a continuation of patristics from the religious point of view alone. The same philosophical elaboration to which religious truth is going to be subjected, is not, in turn, more than the prolongation of an effort that joins with Greek philosophy and fills the preceding centuries. "The emergence of scholasticism was closely associated with these schools which flourished in Italy, France, Spain and England. It predominated in the cathedral schools and in the general studies that gave rise to the European medieval universities, especially between the mid-11th and mid-15th centuries.

As a program, scholasticism began as an attempt at harmonization by medieval Christian thinkers, to harmonize the various authorities of their own tradition, and to reconcile Christian theology with classical and late-antique philosophy, especially that of Aristotle but also Neoplatonism. His training was, however, heterogeneous, since he welcomed not only Greco-Roman philosophical currents, but also Arab and Judaic ones. This encouraged in this movement a fundamental concern to consolidate large systems without internal contradiction that would assimilate the entire classical philosophical tradition. On the other hand, an excessive dependence on argument from authority and a neglect of science and empiricism have been pointed out in scholasticism.[citation required]

But Scholasticism is also a method of intellectual work: all thought had to be submitted to the principle of authority, and teaching could be limited in principle to the reiteration of classical texts, and above all of the Bible (main source of knowledge).. Despite this, scholasticism encouraged reasoning and speculation, since it meant adapting to a rigorous logical system and a structured discourse scheme that had to be capable of exposing itself to rebuttals and preparing defenses.

The scholastics include as main figures Anselm of Canterbury (the father of scholasticism), Pedro Abelardo, Alexander de Hales, Alberto Magno, Juan Duns Scotus, Bonaventure and Thomas Aquinas. Important work has been carried out in the scholastic tradition well beyond the time of Thomas Aquinas, for example, by Francisco Suárez and Luis de Molina, and also among Lutheran and Reformed thinkers.

Etymology

The terms "scholastic" and "scholasticism" derive from the Latin word scholasticus, the Latinized form of the Greek σχολαστικός (scholastikos), an adjective derived from σχολή (scholē), "school". Scholasticus means "of or relating to schools". The "scholastics" they were, more or less, "schoolchildren".

According to Edward Feser, "strictly speaking, there is no such thing as scholasticism" as a single philosophy that was taught in the universities of medieval Europe- The term "scholasticism" it was later adopted by self-described neo-scholastics of the late 19th century and early 20th century. Feser argues that one can speak of a neo-neo-scholasticism that tries to revive neo-scholasticism.

Stages

Ideologically, scholasticism evolved in three phases, from the initial identification between reason and faith, since for the religious the same God is the source of both types of knowledge and truth is one of its main attributes, so that God could not contradict himself on these two paths to truth and, ultimately, if there was any conflict, faith should always prevail over reason, as theology over philosophy.

From there, it passed to a second phase in which there was the awareness that reason and faith had only one area in common.

Finally, at the end of the XIII century and beginning of the XIV, in a third phase, the separation and divorce between reason and faith were greater, as well as between philosophy and theology.

Chronologically, three periods can be distinguished:

- From the beginning of the centuryIX at the end of the centuryXII the scholastic is marked by the controversial question of the universals, which opposes the realistics headed by Guillermo de Champeaux, the nominalists represented by Roscelino and the conceptualists led by Pedro Abelardo.

- The centuryXII at the end of the centuryXIII The entrance of Aristotle takes place, first indirectly through the Jewish and Arab philosophers, especially Averroes, but immediately directly translated from Greek to Latin by Alberto Magno and by Guillermo de Moerbeke, secretary of Thomas Aquinas. The philosophy of theology is distinguished.

- The third encompasses the entire centuryXIV: Guillermo de Ockham deselects the nominalists and opposes tomism, separating and divorceing the philosophy of theology.

Philosophy and Christianity

The foundations of Christian scholasticism were laid by Boethius through his logical and theological essays, and later forerunners (and later companions) of scholasticism were Jewish and Islamic philosophy.

One of the first points that must be taken into account is the influence that philosophers such as Aristotle and Plato have had in the formation of the fundamental ideas of Christianity, both in the thought developed during the first centuries of this era by the Fathers of the Church, as at the height of its philosophy with scholasticism, in the period between the XI and centuries ="font-variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">XIII.

Since its beginnings, Christianity has seen philosophy as a propitious means to understand and deepen the mystery revealed by faith.

All those truths that we can know through our experiences must be reached through the correct use of reason, but with respect to those that have been revealed to us, this must go behind faith, philosophy must be at the service of theology.

Undoubtedly, all these issues remain in Christian philosophy to this day and this is perhaps historical proof that the Christian religion's claim to truth is not foreign to human reason, but rather, on the contrary, she reveals her deepest origin.[citation needed]

Preschool

Pre-scholasticism stems from patristic origins and classical heritage. It was characterized by moments of great moral and cultural decadence due to the absence of administrative unit power and authority, which remained in barbarian towns. Subsequently, Carlos Martel (686-741) came to consolidate the Carolingian empire. The political world was also hierarchical by the Church. For this reason, in the Carolingian renaissance the name of scholastic began to be designated to all those who freed from servile trades, dedicated their free time to study and after Charle the Great (768 -814) made the "Officium Scholasticum" call "scholasficum" to everyone who held a chair in the schools and universities of the Middle Ages.

6th to 9th centuries: beginning of didactic thinking

Pre-scholastic medieval philosophy was marked by traditionalism and submission to authority. The ordering of sentences and application of the method of questions and solutions begins. He also begins a production of text compilations. The main exponents of the period are Boethius and Juan Escoto.

Severinus Boethius

Severinus Boethius (477-524) was a Roman senator, philosopher of the early VI century, author of numerous manuals and translator of works by Plato and Aristotle. He became the main intermediary between classical antiquity and the following centuries. He wrote while imprisoned by the Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great the Consolation of Philosophy, a philosophical treatise on fortune, death, and other subjects, which became one of the most popular and influential works of contemporary art. Middle Ages.

Juan Escoto Erigena

Scotus Eriugena (810-877) was a leading philosopher of the Carolingian Renaissance. His philosophy remains in line with what is known as Neoplatonism in terms of Platonism and the negative (or apophatic) theology of Christianity of Pseudo Dionysus in pantheistic terms.As God is incomprehensible, God does not know himself.

Gerbert of Aurillac

Gerbert of Aurillac (945-1003) achieved great renown as a theologian and philosopher, highlighting works such as On the rational and on the use of reason and On the body and blood of Christ; but it is in his facet as a mathematician that he stood out the most. He introduced to France the Islamic decimal system and the use of zero.

Other Philosophers

- Casiodoro

- San Isidoro

Initial scholasticism

It is called «first scholasticism» or «early scholasticism» that which took place during the centuries IX and XII, a period characterized by the great crusades, the revival of cities and a centralization of papal power that led to a struggle for investiture The renewal of learning in the West occurred with the Carolingian renaissance of the High Middle Ages with the founding of new schools. It was marked by Augustinian thought and the penetration of Aristotelian thought.

9th to 12th centuries: the question of universals

From the beginning of the IX century to the end of the XII the debates focused on the question of universals, which opposed the realists led by Guillermo de Champeaux, the nominalists represented by Roscelino and the conceptualists (Pedro Abelardo).

Anselm of Canterbury

The most outstanding figure of this era was Saint Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109). Considered the first scholastic, his works Monologion and Proslogion had a great impact, centered above all on his controversial ontological argument to prove the existence of God a priori .

Pedro Abelardo

Pedro Abelardo (1079-1142) renewed logic and dialectic and created the scholastic method of the quaestio —a problema dialecticum— with his work Sic et non.

Chartres School

In the 12th century, the School of Chartres is renewed with the figures of Bernard of Chartres (died 1124), Thierry de Chartres, Bernardo Silvestre and Juan de Salisbury. Influenced by Neoplatonism, Stoicism and Arab and Jewish science, their interest was mainly focused on the study of nature and the development of a humanism that would come into conflict with the mystical tendencies of the time represented by Bernardo de Claraval (1091 -1153). The Chartres school was a follower of the Parvipontine school of logic founded by Adam du Petit-Pont (1100-1169), who was a teacher of John of Salisbury himself, Robert de Melun, Guillaume de Soissons, Albéric of Rheims and William of Tire. The Parvipontines of the Chartres school advocated the use of Aristotelian logic in all theological arguments; this brought them into conflict with the mystical schools.

Other Philosophers

Hugo de San Víctor, however, will carry out a reconciliation between mysticism and scholasticism, being also the first to write a Summa in the Middle Ages (Summa Sententiarum).

High schooling

The «High Scholasticism» or «the golden age of scholasticism» was marked by a revival of ancient classical philosophy through the reinterpretation of Aristotelian thought and its Islamic variants (Averroes, Avicenna...), in such a way that way that was reconciled with Christian dogmas. In the Dominican order, Thomistic thought predominated, while in the Franciscans, Augustinianism still predominated.

13th century: heyday of scholasticism

The heyday of scholasticism coincided with the XIII century, when universities were founded and mendicant orders emerged (Dominicans and Franciscans, mostly), where most of the theologians and philosophers of the time come from.

Dominicans and Franciscans

The Dominicans assimilated the philosophy of Aristotle from the Islamic translations and interpretations of Avicenna and Averroes. The Franciscans will follow the line opened by patristics, and will assimilate Platonism, which was much more harmonized with Christian dogmas.

Both orders produced brilliant thinkers. Among the Dominicans, Alberto Magno (1193/1206-1280) and Tomás de Aquino (1225-1274) stand out. Among the Franciscans, Alejandro de Hales, San Buenaventura (1221-1274) and Robert Grosseteste stand out, although the latter also belonged to the Oxford School, much more focused on scientific research and the study of nature and one of whose main figures was Roger Bacon (1210-1292), defender of experimental science and mathematics.

Albert the Great

Albert the Great (1193/1206-1280) was the first to introduce and articulate the Aristotelian texts with faith. He was a teacher of Saint Thomas Aquinas. Alberto was born around the year 1206 in Lauingen (today, Germany), near the Danube; he made his studies in Padua and in Paris. He entered the Order of Preachers, in which he successfully taught in various places. Ordained bishop of Regensburg, he put all his efforts into pacifying towns and cities. He is the author of important works on theology, as well as many on the natural sciences and on philosophy. He died in Cologne in the year 1280.

Thomas Aquinas

Without a doubt, the highest representative of Dominican theology and scholasticism in general is Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) elevated to the rank of Doctor of the Church. In his magnum opus Summa teologica or Summa Theologiae he accepted Aristotelian empiricism and his hylomorphic theory and the distinction between two classes of intellects. From Arab philosophy, Avicenna took the distinction (alien to the Greeks) between being of essence and being (of existence). God makes himself understandable only through a double analogy.

He thus developed a Platonic-Aristotelian fusion, Thomism, which with its cosmological and teleological arguments (Quinque viae) to demonstrate the existence of God have been the fundamental basis of Christian philosophy for many centuries. The demarcation between philosophy and religious belief carried out by Thomas Aquinas will begin the process of independence of reason from the following century and will represent the end of medieval philosophy and the beginning of modern philosophy.

Findance Bonaventure

Juan de Fidanza (1221-1274), known as San Buenaventura, studied at the University of Paris and was ordained a Franciscan. Bonaventure agreed with Thomas Aquinas that it was possible to know the existence of God, his nature, the immortality of the soul, and the universal natural law of good from evil. Contrary to Saint Thomas, he followed Saint Augustine in the need for divine illumination in knowledge and Platonic forms in the mind of God (exemplaryism), giving a more important role to divine grace.

Other Philosophers

- Pedro Hispano

Decay period

The «Scholastic Lowercase» refers to the final phase of scholasticism between the XIV and XV.year 1280. Scholastic thought turned towards mysticism and on the other hand to the study of natural sciences. New currents arose such as nominalism that broke the harmony of faith and previous reason. It is worth mentioning in this period the condemnations of Paris, where the bishops of Paris conducted a series of investigations to prohibit certain teachings of Aristotle and Averroes considered heretical or contrary. to Christian dogma.

14th century: separation of philosophy and theology

In the following century the Franciscans became important. From this period its greatest representatives are Juan Duns Escoto, called Doctor Subtle, and Guillermo de Ockham, for whom the intelligibility of the world and, mainly, that of God, would be firmly questioned; same line of thought that would be continued by his successors and that would result in the decline of scholasticism.

The precedent for both would be the Oxford School (Robert Grosseteste and Roger Bacon) focused on the study of nature, defending the possibility of an experimental science supported by mathematics, against the dominant Thomism. The controversy of universals ended up opting for the nominalists, which left a space for philosophy beyond theology.

John Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus (1266-1308), a Franciscan of Scottish origin, came to the idea of God: the Infinite Being, as a notion reached through metaphysics; this, understood by the Franciscan in its strict Aristotelian sense as the science of being qua being. He thus establishes an autonomy of philosophy and theology, since it is clear that each of these disciplines has its own method and object; although for Escoto theology supposes, of course, a metaphysics.

William of Ockham

But it will be William of Ockham (1290-1349) who will take this development further. His famous principle of economy, called "Ockham's razor", postulated that it was necessary to eliminate everything that was not evident and given in sensitive intuition: "The number of entities should not be multiplied without necessity."

In the act of knowing we must give priority to empirical experience or «intuitive knowledge», which is an immediate knowledge of (particular) reality, since if everything that exists is singular and concrete, there are no abstract entities (forms, essences) separated from things or inherent to them. Universals are only names (nomen) and exist only in the soul (in anima).

This position, known as nominalism, is opposed to the Aristotelian-scholastic tradition, which was fundamentally realist. Universal concepts, for Ockham, are nothing more than mental processes through which understanding unites a multiplicity of similar individuals through a term. Nominalism leads to affirm the primacy of the will over intelligence. God's will is not limited by anything (voluntarism), not even divine ideas can interfere with God's omnipotence. The world is absolutely contingent and must not conform to any rational order. The only possible knowledge must be based on experience (sensitive intuition). Theology is not a science, since it exceeds the limits of reason: experience. After Ockham, philosophy will separate from theology and science will begin its autonomous journey.

It is not concerned with what the movement is but with how it works. This and other authors are the precursors of Galileo Galilei.

Second Scholasticism

However, scholasticism will still have a renewal of a Renaissance character that will emerge in the XV and centuries ="font-variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">XVI with Spain as the main center, and which will be particularly associated with the Dominican and Jesuit orders. This late scholasticism will have in the Spanish Jesuit Francisco Suárez (1548-1617) one of its greatest exponents. In his most important work, the Metaphysical Disputations (1597), written in Latin, the entire previous scholastic tradition is summarized and modernized and the foundations of Hugo Grotius' iusnaturalism or natural law are laid. His work, rich in later inspirations, was highly influential throughout the XVII and XVIII and echoes of it can still be found in Hegel and even in Heidegger. Although it continues the Aristotelian tradition of Spanish philosophy, it adds elements of nominalism.

Thus, for Suárez the distinction between essence and existence is only a distinction of reason and in fact each existence has its own essence. Only God, as being in itself, is capable of perceiving the distinction in being in another, that is, creatures. The cogito of René Descartes arises from the Suarezian notion of created spiritual substance, which he reasons intuitively. Also Gottfried Leibniz's monad (1646-1716) comes from this notion. The distinction between essence and existence as a distinction of reason (Baruch Spinoza's concept of substance) also has its origin in the philosophy of Suárez, and Kant's transcendental subject is inspired by the notion of attribution analogy handled in this scholastic tradition.

Neoscholasticism

In the 19th century there was a revival of scholasticism called «neo-scholasticism» and in the XX a «neo-Thomism» will emerge, whose most representative figures were Jacques Maritain and Étienne Gilson. Both contributed to spreading Thomism in secular culture. Mention should also be made of Désiré Joseph Mercier, Desiderio Nys, A. Farges, Tomasso Zigliara, Fernand van Steenberghen, Leo Elders, M. Grabmann, Armand Maurer, Charles de Koninck, James A. Weisheipl, Jean-Pierre Torrell, Josef Pieper, Pierre Mandonnet, A. D. Sertillanges, Reginaldo Garrigou-Lagrange, Odon Lottin OSB, Gallus M. Manser, Cornelio Fabro, John F. Wippel, etc.

Bertrand Russel quotes in History of Western Philosophy R. H. Tawney, who says that the true descendant of Aquinas is the labor theory of value, the last of the scholars being Karl Marx in economics.

The balance of Thomism in the XX century is very positive. In this century, the work carried out by the Spanish Dominicans deserves to be highlighted. In addition to those already mentioned, the following stand out: Victorino Rodríguez, Santiago Ramírez, Guillermo Fraile OP and Teófilo Urdánoz (authors of History of Philosophy, BAC), Quintín Turiel and Aniceto Fernández. Currently, the following continue to teach the philosophy of Saint Thomas: José Todolí, Juan José Gallego, Jordán Gallego, Vicente Cudeiro, Armando Bandera, Marcos F. Manzanedo, Mateo Febrer, Vicens Igual and Juan José Llamedo. One of the most important Dominican philosophers was the Spaniard Abelardo Lobato, who became rector of the Faculty of Theology in Lugano (Switzerland).

Also the Spanish Jesuit Ramón Orlandis Despuig, founder of the Schola Cordis Iesu (1925) and inspirer of the magazine Cristianidad (1944), who trained Jaume Bofill i Bofill and Francisco Canals Vidal, with who began to know the Thomist School of Barcelona.

There have been many who have contributed to the flourishing of Thomism: Ángel González Álvarez, Leopoldo Eulogio Palacios, Carlos Cardona and his disciple Ramón García de Haro. Likewise, Antonio Millán-Puelles, Osvaldo Lira, Leonardo Castellani, Julio Meinvielle, Francisco Canals and the Thomist school of Barcelona, Juan Vallet de Goytisolo, Jesús García López, Mariano Artigas Mayayo, Luis Clavell Martínez-Repiso, Ángel Luis González, Miguel Ayuso, Rafael Alvira, Rafael Gambra Ciudad, Tomás Melendo, Eudaldo Forment, Armando Segura, Luis Romera, Alfonso García Marqués, Patricia Moya, and Javier Pérez Guerrero.

In Argentina, Tomás D. Casares, Octavio Nicolás Derisi, Alberto Caturelli, Juan José Sanguineti, Juan Alfredo Casaubón, Ignacio Andereggen, Juan R. Sepich (in his early days), Guido Soaje Ramos, the Jesuit Ismael Quiles and the Dominican Domingo Basso, among others.

Recently there has been a renewed interest in the "scholastic" of doing philosophy within the confines of analytical philosophy. Analytical Thomism can be seen as a pioneering part of this movement.

Further reading

- Hyman, J.; Walsh, J. J., eds. (1973). Philosophy in the Middle Ages. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-0-915144-05-1.

- Schoedinger, Andrew B., ed. (1996). Readings in Medieval Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509293-6.

Contenido relacionado

The great Dictator

Samaria

Maximilien Robespierre