Sardinian language

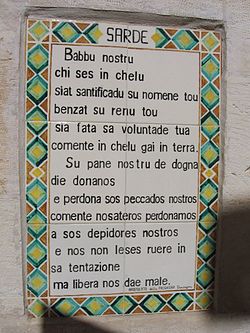

The Sardinian or Sardinian language (sardu [ˈsaɾdu] or limba sarda [ˈlimba ˈzaɾda] / lingua sarda [ˈliŋɡwa ˈzaɾda] in Sardinian) is a Romance language spoken by Sardinians on the Mediterranean island and Italian autonomous region of Sardinia.

Since 1997, the Sardinian language has been recognized by regional and state laws. Since 1999, Sardinian has been recognized as one of the twelve "historical language minorities" of Italy by Law 482/1999, among which Sardinian stands out as the numerically largest, although in constant decline.

Although the community of speakers can be defined as having a "high linguistic awareness", Sardinian is currently classified by UNESCO in its main dialects as a language in serious danger of extinction (definitely endangered), being seriously threatened by the process of linguistic substitution by Italian, whose rhythm of assimilation, engendered from the century XVIII, among the Sardinian population it is already quite advanced. The rather fragile and precarious state in which the language now finds itself, excluded even from the family environment, is illustrated by the report Euromosaic, in which, as Roberto Bolognesi points out, "the Sardinian (the second minority language in Europe by number of speakers) occupies 43rd place in the classification of the 50 languages considered and of those that have been analysed: (a) use in the family, (b) cultural reproduction, (c) use in the community, (d) prestige, (e) use in institutions, (f) use in education".

The Sardinian adult population would no longer be able to hold a single conversation in the ethnic language, this being used exclusively by only 0.6% of the total, and less than fifteen percent, within the youth population, he would have inherited entirely residual abilities in a deteriorated form described by Bolognesi as "ungrammatical slang".

Since the near future of the Sardinian language is far from certain, Martin Harris claims that if the trend cannot be reversed, it will only leave its traces in the language that now prevails in Sardinia, specifically Italian in its variant. regional, in the form of substrate.

Linguistic classification

The question now arises whether the Sardinian should be considered a dialect or a language. The Sardinian, politically speaking, is clearly one of the many dialects of Italy, as is the serbocroata and the Albanian spoken in several towns of Calabria and Sicily. However, from a linguistic point of view, that is a different question. It can be said that sardo has no relation to any dialect of continental Italy; it is an archaic romance language with its own distinctive characteristics, which shows a very original vocabulary in addition to very different morphology and syntax of Italian dialects.Max Leopold Wagner, The Sardinian lingua - Ilisso, pp.90-91

Sardo is an insular language par excellence: it is at the same time the most archaic and the most different group of romance languages.Rebecca Posner, John N. Green (1982). Language and Philology in Romance. Mouton Publishers. The Hague, Paris, New York. p. 171

Sardin, composed of a set of internal variants, is classified as an Insular Romance language: the Insular branch can also be classified as a group of Western Romance languages, since Sardinian shares some characteristics of Western Romance such as plurals in (-s) and the voicing or loss of intervocalic /p, t, k/; however, several authors consider Sardinian a separate branch, as it retains archaic features that were lost in the other Romance languages. It is considered the most conservative of the Latin-derived languages: for example, the historian Manlius Brigaglia notes that the Latin phrase uttered by an ancient Roman Pone mihi tres panes in bertula ("put three loaves of bread in my saddlebag") corresponds to its modern Sardinian translation "Pònemi tres panes in bertula". In addition, the Sardinian substrate (Paleosardo or Nuragus) has also been preserved in some features.

A 1949 study by Italian-American linguist Mario Pei, analyzing the degree of difference from Latin in terms of phonology, inflection, syntax, vocabulary, and intonation, indicated the following percentages (the higher the percentage, the greater is the distance from Latin): 8% Sardinian, 12% Italian, 20% Spanish, 23.5% Romanian, 25% Occitan, 31% Portuguese and 44% French.

In relation to the dialects of the Italian peninsula, Sardinian is incomprehensible to most Italians, since it is its own linguistic group among the Romance languages.

History

Sardinia's relative isolation from mainland Europe encouraged the development of a Romance language that preserves traces of its indigenous pre-Roman language(s). The language has substratum influences from the Paleo-Sardinian language, which some scholars have connected to Euskera and Etruscan. Adstrate influences include Catalan, Spanish, and Italian. The situation of the Sardinian language with respect to the politically dominant ones did not change until fascism and, more clearly, the fifties of the XX< century.

Origin of Modern Sardinian

- Prenurgic and Nurgic Period

The origins of ancient Sardinian, known as Paleosard, are currently unknown. Research has tried to discover obscure, indigenous, pre-Roman roots; the root s(a)rd, present in many place names and denoting the people of the island, is apparently derived from Shirdana (one of the Sea Peoples), although this claim is hotly debated. Other sources trace this root to Σαρδώ, a legendary woman from the Kingdom of Lydia in Anatolia, or to the Libyan mythological figure Sardus Pater Babai ("Father Sardin& #34;).

In 1984, Massimo Pittau claimed that he found the etymology of many Latin words in the Etruscan language after comparing it with the Nuragic language(s). The Etruscan elements, previously thought to originate in Latin, they would indicate a connection between the ancient Sardinian culture and the Etruscans. According to Pittau, the Etruscan and Nuragic languages descended from Lydian (and therefore Indo-European) as a consequence of contact with the Etruscans and other Tyrrhenians from Sardis, as described by Herodotus. Although Pittau suggests that the Tirrenii</ If they landed in Sardinia and the Etruscans in modern Tuscany, their views are not shared by most Etruscologists.

According to Alberto Areddu, the Shirdana were of Illyrian origin, based on some lexical items, unanimously recognized as belonging to the indigenous substratum. Areddu claims that the ancient Sardinians, especially those in the interior areas, supposedly spoke a particular branch of Indo-European languages. In fact, there are some correspondences, both formal and semantic, with the few testimonies of Illyrian (or Thracian) languages and, above all, with its linguistic continuation, Albanian. He finds such correlations: Sard. eni, enis, eniu "yew" = Alb. enjë "yew"; sard. urtzula "clematis" = Alb. urth "hedera"; sard. rethi "tendril" = Alb. rrypthi & # 34;tendril & # 34;, he also discovered some correlations with the world of birds of the Balkans.

According to Bertoldi and Terracini, Paleosardin has similarities with the Iberian and Siculean languages; for example, the suffix -ara on proparoxytones indicates the plural. Terracini proposed the same for suffixes in - / àna /, - / ànna /, - / énna /, - / ònna / + / r / + a paragogic vowel (like the place name Bunnànnaru). Rohlfs, Butler and Craddock add the suffix - / ini / (like the place name Barùmini ) as a unique element of paleosardo. Suffixes in / a, e, o, u / + -rr- found a correspondence in North Africa (Terracini), in Iberia (Blasco Ferrer) and in southern Italy and in Gascony (Rohlfs), with a closer relationship with Basque (Wagner and Hubschmid). However, these early links to a Basque precursor have been disputed by some Basque linguists. According to Terracini, the suffixes in - / ài /, - / éi /, - /òi/, and -/ùi/ are common to Paleosardian and North African languages. Pittau emphasized that this concerns terms that originally end in a stressed vowel, with an attached paragogenic vowel; the suffix resisted Latinization in some place names, which show a Latin body and a nuragus suffix. According to Bertoldi, some place names ending in -/ài/ and -/asài/ indicate Anatolian influence. The suffix -/aiko/, widely used in Iberia and possibly of Celtic origin, and the ethnic suffix in -/itanos/ and -/etanos / (for example, the Sardinian Sulcitans) have also been pointed out as paleosardian elements (Terracini Ribezzo, Wagner, Hubschmid and Faust).

Linguists Blasco Ferrer (2009, 2010), Morvan (2009) and Arregi (2017) have attempted to revive a theoretical connection to Basque by linking words, such as Sardinian ospile "shade, cool place" and the Basque ozpil; the Sardinian arrotzeri "wanderer" and the Basque arrotz "foreigner"; Sardinian galostiu and Basque gorostoi; the Galluros (Corso-Sardinian) zerru "cerdo" and the Basque zerri. Genetic data have found that the Basques are close to the Sardinians.

Since the Neolithic period, a certain degree of variation is also attested in the regions of the island. The Arzachena culture, for example, suggests a relationship between the northernmost region of Sardinia (Gallura) and southern Corsica, which finds further confirmation in Pliny the Elder's Naturalis historia. There are also some stylistic differences between northern and southern Sardinia, which may indicate the existence of two other tribal groups (Balaros and Ilienses) mentioned by the same Roman author. According to archaeologist Giovanni Ugas, these tribes may have influenced the linguistic configuration of the island's dialects.

- Classic period

Circa 9th century and X a. C. Phoenician merchants had made their presence in Sardinia, which was a geographical mediator between the Iberian and Italian peninsulas. In the 8th and 7th centuries, the Phoenicians began to develop permanent settlements, politically organized as city-states in a similar way to the Lebanese coastal areas. It was not long before they began to gravitate around the Carthaginian sphere of influence, whose level of prosperity prompted Carthage to send a series of expeditionary forces to the island; Although initially rejected by the natives, the North African city vigorously pursued a policy of active imperialism and, in the VI century, succeeded in establish their political hegemony and military control over southwestern Sardinia. Punic began to be spoken in the area, and many words also entered Old Sardinian. Names like giara "plateau" (cf. Hebrew "forest, thicket"), g(r)uspinu "nasturtium" (from Punic cusmin), curma "ruda" (cf. ḥarmal "alharma"), mítza "source" (cf. Hebrew mitsa, metza "place from which something emerges"), síntziri "horsetail& #3. 4; (from Punic zunzur "common knotgrass"), tzeúrra "bud" (from Punic zeraʿ "seed"), tzichirìa "dill" (from Punic sikkíria; cf. Hebrew šēkār "beer") and tzípiri "rosemary" (from Punic zibbir) are commonly used, especially in the modern Sardinian varieties of the Campidano, while to the north the influence is more limited to place names, such as Macumadas in the Province of Nuoro or Magumadas in Gesico and Nureci, which derive from the Punic maqom hadash "new city".

Roman rule, beginning in 238 B.C. C., brought Latin to Sardinia, but it was constantly challenged by the Sardinian tribes and could not fully supplant pre-Latin languages, including Punic which, according to votive inscriptions, continued to be spoken into the IV d. Some obscure roots remained unchanged, and in many cases Latin accepted local roots (such as nur, probably from Norax, which makes its appearance in nuraghe, Nurra, Nurri and many other place names). Barbagia, the central mountainous region of the island, derives its name from the Latin Barbaria (a term meaning "land of the barbarians", similar in origin to the word Barbery ), because its people rejected cultural and linguistic assimilation for a long time: 50% of place names in central Sardinia, particularly in the Olzai territory, are not related to any known language. Of the places, on the island there are still some names of plants, animals and geological formations directly traceable to the ancient Nuragic era.

During Roman rule, the island experienced a new period of isolation, in which it became a land of exile among populations considered close to the Africans and dedicated to banditry and piracy. Cicero's invectives are famous, when mocking the Sardinians who rebelled against Roman power, denounced their unreliability due to their supposed African origin, hating their brown skin, their disposition towards Carthage more than towards Rome, and an incomprehensible language.

During the long Roman rule, Latin gradually became the language spoken by the majority of Sardinians. As a result of this process of romanization, the modern Sardinian language is today classified as Romance or Neo-Latin, with some phonetic features resembling Old Latin. Some linguists claim that modern Sardinian, being part of the insular group, was the first language to break away from Latin; all others evolved from Latin as 'continental Romance'.

At that time, the only literature that was produced in Sardinia was mainly in Latin: the native (Paleosardic) and non-native (Punic) pre-Roman languages were already extinct (the last Punic inscription in Bitia, southern Sardinia, is from the century II). Some poems recorded in ancient Greek and Latin (the two most prestigious languages of the Roman Empire) can be seen in the "cave of the viper", in Cagliari (Grutta 'e sa Pibera in Sardinian, Grotta della Vipera in Italian, Cripta Serpentum in Latin), a funerary monument built for Lucius Cassius Philippus (a Roman who had been exiled to Sardinia) in memory of his late wife Atilia Pomptilla. We also have some religious works of Saint Lucifer and Eusebius, both by Caralis.

Although Sardinia was culturally influenced and politically ruled by the Byzantine Empire for almost five centuries, Greek did not enter the Sardinian language, except for some rituals or formal expressions that used the Greek structure and sometimes the alphabet Greek. Evidence for this is found in the condaghes, the first written documents in Sardinia. From the long Byzantine era, there are only a few entries, but they already provide an insight into the sociolinguistic situation on the island where, in addition to the Neo-Latin language used in everyday life, the ruling classes also spoke Greek. Some place names, such as Jerzu (Greek khérsos, "without tillage"), along with personal names Mikhaleis, Konstantine and Basilis, demonstrate Greek influence.

When the Muslims conquered southern Italy and Sicily, communications broke down between Constantinople and Sardinia, whose districts became increasingly autonomous from the Byzantine ecumene (Greek: οἰκουμένη). So, Sardinia returned to the Latin cultural sphere.

Period of the Sardinian Courts

Sardinian was the first Romance language to gain official status, as it was used by the four island Courts, former Byzantine districts that became independent political entities after Arab expansion into the Mediterranean he severed any links between the island and Byzantium. The exceptionality of the Sardinian situation, which in this sense constitutes a unique case in the entire Romanesque panorama, consists in the fact that the official texts were written from the beginning in Sardinian and completely excluded Latin, unlike what happened at the time contemporary in France, Italy and Iberia; Latin, however official, was actually used only in documents relating to relations with the mainland.

One of the oldest documents remaining in Sardinia (the so-called Volgare Letter) comes from the Court of Cagliari and was issued by Torchitorio I of Lacon-Gunale in 1070, using the Greek alphabet. Sardinian then had a greater number of archaisms and Latinisms than the current language, and the documents suffered from the influence of scribes, most of whom were made up of Catalans, Genoese and Tuscans. While earlier documents show the existence of a Sardinian koine, the language used by the various Courts already showed a certain range of dialectal variation. A special position was occupied by the Court of Arborea, the last kingdom of Sardinia in fall to foreign powers, in which a transitional dialect was spoken. The Logu Letter of Arborea, one of the first constitutions in history drawn up in 1355–1376 by Mariano IV and the Queen or "Judge" (judikessa or juighissa in Sardinian, jutgessa in Catalan, giudicessa in Italian) Leonor, was written in this variety Sardinian. It is presumed that the judges of Arborea attempted to unify the various Sardinian dialects in order to be legitimate rulers of the entire island under a single state (the Republica Sardisca "Republic of Sardinia"); this political objective had already been made clear since 1164, when Judge Barisono ordered his great seal to be made with the writings "Baresonus Dei Gratia Rei Sardiniee ("Barison, by the grace of God, King of Sardinia") and Est vis Sardorum pariter regnum Populorum ("The government of the People is equal to the strength of the Sardinians")..

| Extract from the Logudoré Privilege (1080) |

|---|

| « In nomine Domini amen. Ego iudice Mariano de Lacon fazo ista letter ad onore de omnes homines de Pisas pro xu toloneu ci mi pecterunt: e ego donolislu pro ca lis so ego amicu caru e itsos a mimi; ci nullu imperatore ci lu aet potestare istu locu de non (n)apat comiatu |

Dante Alighieri refers to the Sardinians in his work De Vulgari Eloquentia and critically expels them, since according to him they were not Italians (Latii) nor did they have a vulgar, still imitating Latin: "Sardos etiam, qui non Latii sunt sed Latiis associandi videntur, eiciamus, quoniam soli sine proprio vulgari esse videntur, grammaticam tanquam simie homines imitantes: nam domus nova et dominus meus locuntur» ("Let us also eliminate the Sardinians - who are not Italian, but seem to resemble Italians - because only they seem to lack a vernacular of their own and imitate grammar as monkeys to men: in fact, they say domus nova and dominus meus").

This statement must be refuted since Sardinian, on the contrary, evolved on its own to the point of becoming completely unintelligible to non-islanders. Proof of this are two popular verses, dating from the XII century, in which the Provençal troubadour Raimbaut de Vaqueiras compares, in terms of intelligibility, the Sardinian language with German and Berber: «No t'intend plui d'un Toesco / o Sardo o Barbarì» (lit. "I don't understand you more than a German / or Sardinian or Berber").

The Tuscan poet Fazio degli Uberti refers to the Sardinians in his poem Dittamondo as «una gente che niuno non la intende / né essi sanno quel ch'altri pispiglia» ("a people that no one can understand / and that does not know what others say"). The Muslim geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi, who lived in Palermo, Sicily, at court of King Roger II, wrote in his work Kitab Ruyar ("The Book of Roger") that "The Sardinians are ethnically Rûm 'Afàriqah ("Romans of Africa"), live like the Berbers, ignore the other nations of Rūm and are a brave people, never laying down their weapons". In fact, Sardinian was perceived as quite similar to Latin dialects once spoken by North African Christian Berbers, lending credence to the theory that Vulgar Latin in both Africa and Sardinia presented important parallels not only because of ancient ethnic affinities, but also because of a common political past within the Exarchate of Africa. The coincidence between Sardinian and African Latin of several words quite rare, if not absent, in the rest of the Romanesque panorama, such as acina (grape), pala (shoulder), or even spanus in African and spanu in Sardinian ("reddish"), would be a proof, for J. N. Adams, that a good deal of vocabulary was shared between Africa and Sardinia.

The literature of this period consists mainly of legal documents, apart from the aforementioned Letter of Logu. The first document in which some element of the language can be found dates back to 1063, with the act of donation by Barison I° de Torres addressed to the abbot Desiderio for the abbey of Montecassino. Other documents are the Volgare Letter (1070–1080), the "Loguedores Privilege" (1080) the Donation of Torchitorio preserved in the Marseille archives (1089), the Marseillaise Charter (1190–1206) and a communication of 1173 between the bishop of Civita Bernardo and Benedetto, the administrator of the Cathedral of Pisa The statutes of Sassari (1316) and Castelgenovese (c. 1334) are written in Logudorese Sardinian.

The first chronicle written in lingua sive ydiomate Sardinian dates back to the second half of the 13th century, following the typical stylistic features of the time. The manuscript, written by an anonymous person and now preserved in the State Archive of Turin, bears the title Condagues de Sardina and traces the events of the judges who succeeded each other in the Court of Torres; the last critical edition of the chronicle would have been republished in 1957 by Antonio Sanna.

Iberian Period

The enfeudation of the island by Boniface VIII in 1297, without having taken into account the state realities that already existed within it, led to the founding, even if only nominal, of the Kingdom of Sardinia, thus marking the end of Sardinian independence and also a long period of wars, which ended with the victory of the Crown of Aragon in Sanluri (1409) and with the consequent waiver of the right of succession by William III of Narbonne. Any attempt at rebellion was systematically neutralized, such as that of the city of Alghero (1353) and that of Macomer (1478). Then a process of assimilation began in all social aspects; For the first time, a situation of imbalance and linguistic hierarchy was established, in which Catalan took the status of hegemonic language and Sardinian, although official (the Aragonese extended the Logu Charter to the entire island and remained in force until 1827), was relegated to a secondary position. This was especially evident in the south of the island, whose variety received a large number of loanwords from the dominant language; In Cagliari, a city that, like Alghero, underwent a process of total repopulation by the Aragonese, there were expressions such as No scit su cadelanu ("He does not know [to speak] Catalan& #34;) to indicate a person who had not been sufficiently cultured. Agreeing with Giovanni Fara in his De Rebus Sardois, the lawyer Segimon Arquer, author of the work Sardiniae brevis historia et descriptio (whose paragraph on language would have been extrapolated also by Conrad Gessner in his "On the different languages used by the different nations of the world"), he said that the citizens chose Catalan as their prestigious language, unlike the neighborhoods, where people continued to speak Sardinian The Jesuits had initially promoted a language policy in favor of the Sardinian language, but later changed it in favor of Spanish. The goigs (in Sardinian gozos/goccius) contributed to the spread of Catalan at a popular level.

In that period we do not have a detailed written documentation of Sardinian, even though it was the language that the population mostly spoke. There are the examples of Antoni Cano, who wrote Sa Vitta et sa Morte, et Passione de Sanctu Gavinu, Brothu e Ianuariu, written in the XV and published in 1557.

More interesting is the work Spiritual Rhymes by Hieronymu Araolla, which sets itself the task of "magnificare et arrichire sa limba nostra sarda (magnify and enrich Sardinian, our language) in the same way that French, Spanish and Italian poets had done for their respective languages (see for example la Deffense et illustration de la langue françoyse, il Dialogo delle lingue etc.); he has the merit of having clarified for the first time what would later be known as the "question of the Sardinian language", deepened by other authors.

Antonio de Lofraso, who was born in Alghero (a city that he remembers fondly in several verses) and lived in Barcelona, was probably the first intellectual to write lyrical love compositions in the Sardinian language, although the most widely used language was Spanish with abundant Catalanisms; Inside the work The ten books of Fortune of Love (1573) two sonnets appear in Sardinian, "Cando si det finire custu ardente fogu" and «Supremu gloriosu exelsadu», and a poem in real octaves: ...Non podende sufferare su tormentu / de su fogu ardente innamorosu. / Videndemi foras de sentimentu / et sensa un hora de riposu, / pensende istare liberu e contentu / m'agato pius aflitu e congoixosu, / in essermi de te señora apartadu, / mudende ateru quelu, ateru istadu...

In 1624, during the attempts to reorganize the Monarchy by the Count-Duke of Olivares in Sardinia, a greater use of Spanish to the detriment of Catalan became apparent. Spanish, unlike Catalan, which managed to penetrate every island neighborhood, had remained a fairly elitist language and pertinent to literature and education. Be that as it may, Sardinian remained the only and spontaneous code of communication for the majority of people, respected and also learned by the conquerors. Spanish thus had a profound influence on the Sardinian ruling class, especially in those words, styles and cultural models due to the prestigious international role of the Habsburg Monarchy, as well as the Court. Most Sardinian authors wrote in both Spanish and Sardinian, and would have done so until the XIX, like Vicente Bacallar y Sanna, who was one of the founders of the Royal Spanish Academy.

The sociolinguistic situation remains such that the two colonial languages were spoken in the city and Sardinian tenaciously resisted in the countryside and in all the villages, as reported by Ambassador Martín Carillo (author of the famous ruling on the Sardinians, who would be a town of few, crazy and badly united), the Llibre dels feyts d'armes de Catalunya («speak the Catalan language molt polidament, axì com fos a Catalunya») and the Sasaran rector of the Jesuit University Baldassarre Pinyes, who wrote: “as far as the Sardinian language is concerned, know your paternity that they do not speak it in this city, nor in Alghero nor in Cáller, only in the villages». The notable presence of Valencian and Aragonese feudatories in the northern half of the island, as well as mercenaries who came from there, has made Logudorese the variant most influenced by Castilian.

Sardinian was one of the few languages whose knowledge was necessary to be official of the Spanish tercios. Only those who spoke Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese or Sardinian could make a career.

Meanwhile, the Orgolese parish priest Ioan Matheu Garipa, in the opera Legendariu de Santas Virgines, et martires de Jesu Christu, which he translated from Italian (the Leggendario delle Sante Vergini e Martiri di Gesù Cristo), highlighted the nobility of the Sardinian language in relation to classical Latin and attributed it in the Prologue, like Araolla before him, an important ethnic and national value:

The apo voltadas in sardu menjus qui non in atera limba pro amore de su vulgu [...] qui non tenjan bisonju de interprete pro bi-las decrarare, et tambene pro esser sa limba sarda tantu bona, quanta participat de sa latina, qui nexuna de sarntas limbas si plàtican est tantu parente assa latina [...] Et quando cussu non esseret, est sufficient motiuu pro iscrier in Sardu, vider, qui totas sas nationes iscriven, " istampan libros in sas proprias limbas naturales in soro, preciandosi de tenner istoria, " materias morales iscritos in limba vulgare, pro qui totus si potan de cuddas aprofetare. Et pusti sa limba latina Sarda est clara & intelligibile (iscrito, & pronounceda comente conuenit) tantu & qui non quale si querjat dessas vulgares, pusti sos Italianos, & Ispagnolos, & totu cuddos qui tenen platica de latinu la intenden medianamente.

According to the philologist Paolo Maninchedda, these authors, starting with Araolla, "did not write about Sardinia or in Sardinian to fit into an insular system, but to inscribe Sardinia and its language - and with them, themselves - in a European system. Elevating Sardinia to a cultural dignity equal to that of other European countries also meant promoting Sardinians, and in particular educated Sardinians, who felt they lacked roots and belonging in the continental cultural system".

Piedmontese period and Italian influence

The War of the Spanish Succession resulted in the passage of the island to Austrian sovereignty, which was later confirmed by the treaties of Utrecht and Rastadt (1713-1714); however, it only lasted four years, since in 1717 a Spanish fleet reoccupied Cagliari, and in the following year, by means of a treaty that was ratified in The Hague (1720), Sardinia was assigned to Victor Amadeo II of Savoy in exchange for Sicily. However, this transfer did not initially imply social or linguistic changes: Sardinia maintained its Iberian character for a long time, so much so that only in 1767 the Aragonese and Spanish dynastic symbols were replaced by the Piedmontese Savoy cross. The Sardinian language, although practiced in a state of diglossia, it had never been reduced to the sociolinguistic rank of "dialect", its linguistic independence being universally perceived and spoken by all social classes; Castilian, on the other hand, was the prestigious linguistic code known and used by the social strata of the middle culture, at least, for what Joaquín Arce refers to it in terms of a historical paradox: Spanish had become the common language of the islanders in the same century that they ceased to be officially Spanish to become Italian. Given the current situation, the Piedmontese ruling class, in this first period, limited itself to maintaining the local political and social institutions, taking care to empty them of meaning at the same time.

This position was due to three eminently political reasons: firstly, the need, initially, to respect to the letter the provisions of the Treaty of London, signed on August 2, 1718, which imposed respect for the fundamental laws and privileges of the new ceded Kingdom; secondly, the need not to generate friction on the internal front of the island, largely pro-Spanish; thirdly, and lastly, the hope, still in gestation on the part of the Savoys, of being able to get rid of Sardinia and recover Sicily. This prudence is found in June 1726 and January 1728, when the king expressed the intention not to abolish Sardinian and Spanish, but only to spread knowledge of Italian more. in a special study, commissioned and published in 1726 by the Barolan Jesuit Antonio Falletti, entitled "Memoria dei mezzi che si propongono per introdurre l'uso della lingua italiana in questo Regno&# 34;, in which the administration of Savoy was recommended to apply the learning method ignotam linguam per notam expōnĕre ("presenting an unknown language [Italian] through a known language [Spanish]").

However, the Savoys imposed Italian on Sardinia in 1760 due to the geopolitical necessity of moving the island away from Spanish cultural and political influence and aligning Sardinia with Italian Piedmont, where the use of Italian Italian had been consolidated for centuries, officially reinforced by the Edict of Rivoli. In 1764, the order was extended to all sectors of public life, parallel to the reorganization of the Universities of Cagliari and Sassari, which saw the arrival of continental personnel, and that of lower education, which established the sending of teachers from Piedmont to compensate for the absence of Italian-speaking Sardinian teachers. This maneuver is not mainly due to the promotion of Italian nationalism on the Sardinian population, but rather a project of geopolitical strengthening of the Savoy over the cultured class of the island, still closely linked to the Iberian Peninsula, through linguistic-cultural alienation and the neutralization of elements that bore traces of previous domination. However, Spanish continued to be widely used in parish registers and official records until 1828, and the most direct consequence was a new marginalization of the Sardinian language, opening the way for the Italianization of the island. For the first time indeed, even the wealthiest and most powerful families in rural Sardinia, the printzipales, began to perceive Sardinian as a disadvantage. The French matrix administrative and penal system introduced by the Savoys, capable of After spreading in an articulated way in all the towns of Sardinia, it represented for the Sardinians the main channel of direct contact with the new hegemonic language; for the higher classes, the suppression of the Jesuit order in 1774 and its replacement by the pro- Piarist Italians, as well as works of the Enlightenment, printed on the mainland, played a considerable role in their primary Italianization. At the same time there was some effort on the part of Piedmontese cartographers to replace Sardinian place-names with ones in Italian; while many of them remained intact, many other names were crudely adapted to an entirely different form: one of the most prominent examples is the small island of Mal de Ventre, whose current Italian name, meaning "stomach ache', is actually an adaptation of the Sardinian word Malu 'Entu, which means "bad wind" instead (the island is continuously exposed to the mistral).

At the end of the 18th century, following the trail of the French Revolution, a group of the Sardinian middle class planned to secede of the ruling class of the continent and institute a Sardinian republic under French protection; throughout the island, various political pamphlets printed in Sardinian were illegally distributed, calling for a mass revolt against the Piedmontese government and the abuse of the barons. The most famous literary product of that period of political turmoil was the poem Su patriottu sardu a sos feudatarios, which is a testament to French-inspired democratic and patriotic values, as well as the situation of Sardinia under feudalism.

The first systematic study on the Sardinian language was written in 1782 by the philologist Matteo Madau, with the title Il ripulimento della lingua sarda lavorato sopra la sua antologia colle due matrici lingue, la greca e la latina. Complaining in the introduction of the general decline of the language, Madau's patriotic intention was to chart the ideal path by which Sardinian could rise to final recognition as the island's national language; However, the climate of repression of the Savoy government against Sardinian culture would have led Madau to veil his proposals with literary intent, ultimately proving incapable of translating them into reality. The first volume of comparative dialectology was produced in 1786 by the Catalan Jesuit Andrés Febres, known in Italy under the false name of Bonifacio d'Olmi , upon his return from Lima, where he had published a book on Mapuche grammar in 1764. After Moving to Cagliari, he became interested in Sardinian and did research on three specific dialects; the objective of the work, entitled Prima grammatica de' tre dialetti sardi, was <<give the rules of the Sardinian language>> and encourage Sardinians to <<cultivate and favor the language of their homeland, alongside Italian>>. The government of Turin, after examining the work, decided not to allow its publication: Victor Amadeo III considered it an affront that the book contained a bilingual dedication addressed to him in Italian and Sardinian, an error that his successors would avoid, using only Italian. In the climate of monarchic restoration that followed Angioy's failed revolution, other Sardinian intellectuals, all characterized by an attitude of devotion to their island and proven loyalty to the House of Savoy, raised the "question of language" Sardinian", but generally using Italian as the language to transmit the texts. A short distance from the station of the anti-Piedmontese revolt, in 1811, we find the timid publication of the priest Vincenzo Raimondo Porru, which, however, referred only to the southern variant (hence the title Saggio di grammatica del dialetto sardo meridionale) and, out of prudence towards the rulers, he expressed himself only in terms of learning Italian, instead of protecting Sardinian. sarda nationale ("Sardinian national spelling") of 1840 raised a Sardinian variant unanimously accepted as koinè illustrious for its close relationship to Latin, similar to how the Florentine dialect had established itself in Italy as "illustrious Italian".

The relationship between the recently imposed Italian language and the native one had been perceived from the beginning by the islanders, educated and uneducated alike, as a relationship (albeit unequal in terms of political power and prestige) between two very different, and not between a language and one of its dialects as in continental regions, where Italian had been adopted since the Middle Ages as the official language. The centuries-old Iberian period also contributed to the fact that the Sardinians felt relatively separated from Italian and its cultural sphere, and the Spanish themselves already considered Sardinian as a distinct language with respect to both their own and Italian.

The jurist Carlo Baudi di Vesme explicitly proposed a complete language ban in order to turn the islanders into "civilized Italians". Primary education, taught in a language with which Sardinians unfamiliar, spread Italian for the first time in history to the various Sardinian peoples, marking the troubled transition to the new dominant language; the school environment, which used Italian as the only means of communication, became a microcosm within the monolingual Sardinian villages at that time. The educational system therefore contributed to a slow diffusion of this language among the natives, and for the first time caused a process of linguistic substitution. Sardinian was presented as a language spoken by socially marginalized people, as well as sa limba de su famine or sa lingua de su famini ("the language of hunger& #34;), responsible for the secular isolation and poverty of the island, and on the contrary, Italian as an agent of social emancipation through sociocultural integration with the continental territory. In 1827, the Logu Charter, the historic Sardinian legal corpus or «consuetud de la nacimiento sardesca», was finally abolished in favor of the Leggi civili e Criminali del Regno di Sardegna by Carlos Félix.

Despite such policies of cultural assimilation, later accompanied by the loss of residual political autonomy through the perfect merger and unification of the Italian peninsula, the anthem of the Piedmontese Kingdom of Sardinia was the so-called Hymnu Sardu (or Cunservet Deus su Re), whose text was entirely in Sardinian; it was replaced by the "Royal March" when the Italian peninsula was unified.

During the mobilization for World War I, the Italian Army forced all Sardinians to enlist as Italian subjects and established the Brigata Sassari on March 1, 1915 at Tempio Pausania and Sinnai. Unlike the other infantry brigades in Italy, the Sassari's recruits were only Sardinians. It is currently the only unit in Italy with a hymn in a language other than Italian: Dimonios ("Devils"), written in 1994 by Luciano Sechi. Its title derives from Rote Teufel (German for "red devils"). However, conscription played an important role in the language change.

The policy of forced assimilation culminated in the twenty years of the fascist regime which, especially when the campaign of autarchy was carried out, led to the decisive entry of the island into the national cultural system through the combined efforts of the system education and the one-party system, in a crescendo of fines and bans that led to the further sociolinguistic decline of Sardinian. The restrictions got to the point where proper names were changed to make them sound 'more Italian'. During this period, the Sardinian Hymn of the Piedmontese Kingdom was an opportunity to speak a regional language in Italy without any sanction, because, as a fundamental part of the royal family's tradition, it could not be prohibited. Catholic priests and fascists practiced strict obstructionism against improvised sung poetry: paradigmatic is the case of Salvatore Poddighe, a political poet who committed suicide out of despair after the confiscation of his work Sa Mundana Cummédia .

Contemporary Period

After the Second World War, awareness of the danger of Sardinian extinction did not seem to concern Sardinian elites, and the issue entered the political space later than in other European peripheries marked by the presence of ethnolinguistic minorities; the Sardinian ruling class, now Italianized, had already discarded Sardinian, as both the Sardinian language and culture continued to be blamed for the underdevelopment of the island. At the time of drafting the statute in 1948, the legislator central decided to specify the "Sardinian speciality" as a criterion for political autonomy only for a couple of socioeconomic issues, stripped of considerations related to cultural, historical and geographical identity; on the contrary, these considerations were considered as a possible prelude to more autonomist or independentist instances. Finally, the 1948 special statute did not recognize any particular geographic condition about the region or mention distinct cultural and linguistic elements, preferring instead to focus on centrally-funded plans (baptized with the Italian name piani di rinascita) for the development of heavy industry.

Assimilation policies continued during the post-war period, when the dismantling of Sardinian culture, labeled by the education system as a symbol of scorn, was presented as the only form of economic and cultural development for the island. Many historical sites and various objects related to the daily activities of Sardinia were Italianized, by means of another name in Italian (thus replacing the original one) and the systematic removal of any connection with the island. In addition, the Ministry of Public Education Italian had invited the school directors to monitor and record all Sardinian teachers involved in any activity related to the language.

The mass media (particularly the Radiotelevisione Italiana) and compulsory education (where the use of the Sardinian language had been highly discouraged through daily humiliation) popularized in Sardinia the Italian even more, without a parallel project of teaching Sardinian; in the same contemporary period it has been observed that, in the face of a popular will favorable to teaching and making Sardinian official, divisions, disinterest and opposition still remain within the political and legal world of the state, the University, the media current communication and intellectuals, who in that way feared a separation from the framework of Italian culture. The rejection of the native language, together with a rigid model of education in the Italian language, corporal punishment and shame, led to poor schooling for Sardinians.

Since the 1960s, there have been various political and cultural campaigns in favor of bilingualism. One of the first instances came in a resolution adopted by the University of Cagliari in 1971, calling for national and regional authorities to recognize Sardinians as an ethnolinguistic minority and Sardinian as the co-official language of the island. Some acclaim in Sardinian cultural circles followed the patriotic poem No sias isciau ("Don't be a slave") by Raimondo (Remundu) Piras, a few months before his death in 1977, urging bilingual education to reverse the trend of de-sardization. After many claims by the Sardinians, who saw this process as the final death of the Sardinian people, three separate bills were presented to the Regional Council in the 1980s, calling for concrete cultural and political autonomy and also the recognition of the Sardinians as an ethno-linguistic minority.

In the 1990s, there was a revival of music in the Sardinian language, ranging from the more traditional genres (cantu a tenore, cantu a chiterra, gozos etc.) to rock (Kenze Neke, Askra, Tzoku, etc.), hip hop and rap (Quilo, Sa Razza, Malam, Menhir, Stranos Elementos, Randagiu Sardu, Futta etc.): artists use the language as a medium to promote the island and look at its long-standing problems. There are also a few movies (such as Su Re, Beautiful Butterflies, Treulababbu, Sonetaula etc.) dubbed in Sardinian. After a signature campaign, it has become possible to change the language settings on Facebook from any language to Sardinian.

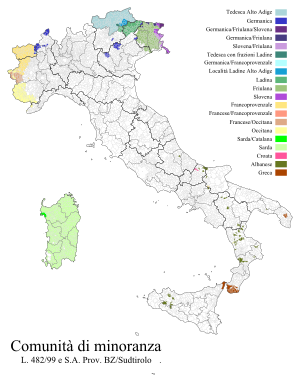

In 1997, the sardin was recognized by Regional Law 26/1997 as a language of the Sardinian Autonomous Region after Italian. Finally, activism made it possible for the formal recognition of twelve minority languages (Sardinia, Albanian, Catalan, Catalan, German, Greek, Slovenian, Croatian, French, Franco-Provenzal, Friulano, Ladino and Occitano) in the late 1990s by National Law 482/1999, in accordance with art. 6 of the Italian Constitution. Although the first section of said law establishes that Italian is the only official language of the Republic, several provisions are included to normalize the use of said languages and allow them to become an integral part of the national fabric. However, Italy (Italy (Italy (Italy (Italy (Italy (Italy (Italy (Italy (Italy (together with France and Malta) it has not ratified the European Charter of Minority or Regional Languages.

Today, which stands out through analysis seems to be a regression, slow but constant and very deep, of any active and passive competence, for political and also socio -economic reasons (the use of the Italian presented as social progress, On the contrary, a stigma associated with that of the sardinity, the gradual depopulation of the internal neighborhoods and the mutual understanding with the languages of the island that are not sardos, etc.): Note that, compared to 68% of people who speak the Sardinar in a situation of Diglosia, among school -age young That, with the exception of sub -regions (enjoyment, barbagia and baronìa) that remain the main bastions of the language, the island is totally Italianized. For these reasons, UNESCO classifies the language and all its variants seriously danger of extinction ( definitely endangered ).

The Euromosaic Research Group, commissioned by the European Commission with the intention of finding out the linguistic situation in the European territories marked by ethnolinguistic minorities, concludes its report as follows:

It seems to be another minority language in danger. Agencies responsible for the production and reproduction of the language no longer play the role they played in the last generation. The educational system does not support language, production and reproduction in any way. The language does not enjoy any prestige and in the working contexts its use does not come from any systematic process, but is merely spontaneous. It seems to be a language relegated to very localized interactions between friends and relatives. Its institutional base is extremely weak and is in continuous decline. However, there is some concern among their speakers, who have an emotional connection with the language and their relationship with the Sardinian identity.Report "Sardinian language use survey", Euromosaic, 1995

While the practice of the Sardinian language is in decline, that of regional Italian, called with ironic contempt by the Sardinian linguistic community italianu porcheddinu ("dig Italian"), It is increasing in the new generations.

The sociolinguistic subordination of the Sardinian to Italian has led to a process of gradual degeneration of the Sardinian language in a patois labeled as regional Italian. This new linguistic code, which arises from the interference between Italian and Sardinian, is particularly common among the less privileged cultural and social classes.Report "Sardinian in Italy", Euromosaic, 1995

There is an important division between those who believe that the protection of the language has come too late, also affirming that it is a difficult task to make a decision to unify the language, and those who believe that, on the contrary, it is essential to invest the trend, looking at examples such as Catalan. A bill from the Monti government, which has not actually been approved (indeed, the Italian state has not yet retified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages), should have further reduced the level of protection of the language Sardinian, which was already quite low, differentiating between languages that are protected by foreign states (German, Slovene and French) and others that have never had that possibility. This has been seen as an abuse of the language, and therefore has provoked a certain reaction on the part of some intellectuals and politicians. Attempts, on the part of some Sardinian students, to present the high school or secondary education exam speaking this language.

Social and cultural aspects

Geographic distribution

The varieties traditionally ascribed to "Sardo" they are used throughout the island of Sardinia, with the exception of the old town of Alghero (where archaic Catalan is spoken), and on the surrounding smaller islands, except for San Pietro and part of Sant'Antioco (where it persists the Ligurian dialect tabarquino). Although among the varieties traditionally ascribed to Sardinian it is convenient to differentiate between Sardinian proper and the Sardinian-Corsican languages of Sardinia. The latter include the Sasares and the Galures.

Sardinian language groups and variants

Sardinian proper is made up of two main groups:

- The logudorous sardo (sardu logudoresu), which is spoken in the north and part of the center of Sardinia, understands in turn the dialects of the common logudorés and the nuorés sardo (sardu nugoresu); some of the nurtures (more precisely the ones spoken in the Baronías area, in the northeast of the island) have the reputation of being the closest to the Latin. The Logudorés, traditionally, has always enjoyed great literary prestige and has manifested much cultural vivacity.

- The country sardo (sardu campidanesu), which is spoken in the historical-geographic region of Campidano, that is in the central-meridional part of Sardinia, is the most spoken variety on the island, besides being the language of its capital, Cagliari.

Traditionally, the following variants are considered Sardinian dialects, although they present a grammatical structure more similar to Corsican and with strong Ligurian and Tuscan influences:

- The gallure (gadduresu), spoken in the northeastern part of the island, in Gallura, and related to the grammatical structure and pronunciation with the southern dialects of Corsica, due to the notable migratory influences.

- The Sasars (sassaresu), spoken in Sassari, in Porto Torres and in surrounding areas, has intermediate features between the Welsh and the Logudorés, also derived from the strong influence exerted by the Pysanos, Genoese and Spanish rulers.

Institutional recognition

The Sardinian language has been recognized by regional law No. 26 of October 15, 1997 as the second official language of Sardinia, along with Italian. The regional law applies and regulates some rules of the Italian state in protection of linguistic minorities. The ISO 639-3 codes are:

- wild boar: "sro"

- sausages: "src"

- galurés: "sdn"

- "sdc"

This language has been recognized by the Italian Parliament with law 482/1999 as a "historical linguistic minority" from Italy.

Linguistic description

Phonetics and phonology

Phonetically and phonologically, Sardinian shares features both with the southern Italian linguistic varieties and with the Ibero-Romance languages, especially with Catalan, Spanish and Asturian. Among its most important characteristics are:

- System of five vowels: /a, e, i, o, u/ without phenological distinction of opening in e and orLike in Spanish.

- Conservation of i and the u Latin briefs, which in various Romance languages became e and or, thus losing the difference between i/e and u/o. In that aspect of the bells it is considered that the Sardinian is the most conservative Romance language since the rest of the Romance languages altered their bells according to the vocálic amount, and only the Sardinian retained in all cases the original bell.

- Absence of diptongation e and or brief Latins, as in the Galician-Portuguese languages, what does happen in Spanish and Italian (in open syllables).

- Betacism: neutralization of b/v for the first: biriSee. In other cases we can have both life/bide possibilities, "life".

- La b initial word in most cases is pronounced with a sound exactly like Spanish, between b and v. This sound, just as in Spanish, is more appreciated if the b in pronunciation comes preceded by a vocálic sound, that is, for example after the articles in singular and if the s of the articles and of the plural demonstrations falls, normative case in many varieties of the sardo, as well as in Andalusian or South American Spanish: sas bacas ("sa'bàccasa"), the cows, sas boghes ("sa'bòghese"), the voices, sa beridade, la verdad, custas besidas ("custa'bessìdasa", estos salidas. But we also have the strong sound of the pbLike in sos babbos ("so'bbàbboso"), the parents.

- Elision of the bOf the v and the g initial when preceded by a word that ends in vowel: s'aca (sa baca, cow), his 'intu (his bentuthe wind, her. (his gatuThe cat. Here too, there are exceptions: his babbu (the father). In the southern variant of the nuorés (Fonni villages, Orgosolo, Ovodda, etc.), the c and the f: his 'ane (his Cane, dog/can), his 'edu (your faithyoung people), 'Onne (Fonni). These elisions are also common in Welsh.

- Elisión de la -v- intervocálica latina: NOVU No..

- Conservation in several words of Latin watch [k] to palatal vowels e, i that in other Romanesque languages became dental palatals or fricatives: VOCEM boghe/boche ['boge] "voz", DECEM deghe/deche ['deke] "ten", CENARE chenare/chenare ['kenare] "cenar." Share with the Dalmatian (dic, vauc and chenur) that also retained the original sound -k but only before -e.

- Sonorization of the Latin intervocálic deafness and, unlike Spanish, the phenomenon is also given in the initial deaf occlusives: Fuck! ['puθu] or ['putsu], well, his fucking [su'βuθu] or [su'βutsu], the well; curl [kur'tura], culture, sa curtura [sagur'tura], culture.

- Epenthetic mouth in words beginning by r-: the "resulted," arrenuntziai "renunciate" urrei "king." This phenomenon is not given in the classical logudore variety: result, renuntziare, re(i).

- In the campidane dialect, only three vowels /a, i, u/ can appear in atone syllable.

- In the Logudorese dialect, in the nuorés and even in the northern countryside, there is always epentical vowel in the Latin words that began by s+consonante, as in Spanish, Portuguese and Catalan. In the sardo this vowel is the i and not the e: s'istòriathe story, s'istaduThe state, Ispannia/Ispagna, Spain, s'iscola, school, s'istrumentuthe instrument, etc.

- In the pronunciation, add a paragogic vowel at the end of the words that end with s. This vowel is always the last one that appears in the word in question: "beware", sos òminesThe men, "sa'dòmoso", sas domosthe houses, "custas còsasa", You quote thingsthese things, "Bear yourself," Porto Torresetc. This phenomenon should not be transferred to the written language.

Lexical comparison

The numerals in different Romance varieties of Sardinia are:

GLOSA Sardo Corso Achievements Campidanés Galurés Sasars '1' a

unu / Onea

unu / Onea

unu / Onea

unu / One'2' du)s(o) / duas(a)

Duos / Duasduz(u) / duas

duus / Duasdui

duidui

dui'3' t margin

Three.t margin

Three.t

tret

tre'4' bat) margin(o)

bat(t)orkwatɾ hunguu

cuat(t)rukat felt

cattrukwat eclipseu

Cuattru'5' kimb

Chimbeiŭku

cincuiŭku

cincuiŭku

tzincu'6' strata(e)

ses(i)

sess

seis

sei'7' stratatɛ

set(t)estratatii

set(t)is messing around

settis messing around

setti'8' t

ot(t)ot u

ot(t)uttundau

ottuttundau

ottu'9' nɛ

No.##

No##

Noniβi

nobi'10' dŭ

deghedŭ

dexidŭi

decid

dezzi

Sardinian distinguishes between masculine and feminine forms for the numerals '1' and '2', for all those ending with '1' excepting the '11', '111', etc., and also for all the hundreds from '200', similarly to what happens in Spanish and in Portuguese.

Comparison table of Neo-Latin languages (for double names in Sardinian, the Logudorese name appears first and then the Campidanese name):

Latin French Asturleon Italian Castellano Occitan Catalan Aragonés Portuguese Gallego Romanian Sardo Sassarés Gallurés Corso Sicily KEY clef/

Cléchave / key Chiave Key clau clau clau chave chave cheie crae/

craiCiabi chiaj/ciai chjave/

chjavichiavi NOCTE(M) nuit nueite/nueche Notte night nuèit/

nuèchnit nueit noite noite Noapte notte/notti notti notti notte/notti notti CANTARE blacker sing sing sing sing sing sing sing sing cânta sing/cantai cantà cantà cantà sing CAPRA chèvre goat capra goat goat/

crabagoat craba goat goat capra craba crabba capra/crabba capra capra LINGUA langue Ilingua lingua tongue lenga/

tongueFilled. Luenga Line lingua limbă limba/

lingualinga linga lingua lingua PLATEA place praza/plaza piazza Square plaça plaça Square praça praza piaţă pratza piatza piazza piazza chiazza PONTE(M) pont Put on. Put on. Bridge pònt pont puent Put on. Put on. pod (bridge)

'pasarela'ponte/ponti ponti ponti Hit.

pontiponti ECCLESIA Eglise eigrexa/ilesia Chiesa church glèisa English ilesia Igreja igrexa biserică Cheja/cresia jesgia ghjesgia ghjesgia cresia HOSPITALE(M) Hôpital hospital ospedale hospital satellite/

espitauhospital ital hospital hospital spital ispidale/ispidali ippidari spidali/uspidali spedale/

uspidalispitali CASEUS

lat. vulg.FORMATICU(M)fromage queisu/quesu formaggio/ Shit.

cheese formatge formatge form/

cheeseI demand queixo brânză

(caş 'requeson')casu casgiu casgiu casgiu furmàggiu/

caciu

Morphology and syntax

In many respects, Sardinian differs quite clearly from the other Neo-Latin languages, especially in the verb.

- The simple future: formed by the auxiliary àer ("do") plus preposition "a" and infinitive. Yeah.: apo to narrer ("I shall say"), as a narrer ("you shall say").

- Conditional: Formed using a modified form of verb ♪ ("must") plus the preposition "a" (optional) and the infinitive. Yeah.: (a) narrer ("did"), days (a) ("did") or with a modified form of verb àer ("do") more "a" and the infinitive: apia a narrer, apias a narre.

- Progressive form: formed with the auxiliary esser ("being") plus the gerundium. Yeah.: so go ("I'm going/going").

- Negative: analogous to Romanesque-iberic languages, the negative imperative is formed using denial No. plus the subjunctive. Yeah.: Don't go. ("do not go/andes").

Spelling

The language had already been standardized since the Middle Ages in the two Logudoreses and Campidaneses models, but there is no unified orthography accepted by all. However, the Region of Sardinia and many institutions use the spelling of the Limba Sarda Comuna (LSC), "common Sardinian language".

Contenido relacionado

Sindarin

Aitken's Law

North American languages