Santiago Ramon y Cajal

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (Petilla de Aragón, Navarra, May 1, 1852-Madrid, October 17, 1934) was a Spanish physician and scientist, specializing in histology and pathology. He shared the 1906 Nobel Prize in Medicine with Camillo Golgi "in recognition of his work on the structure of the nervous system". He pioneered the description of the ten synapses that make up the retina. Through his investigations of the mechanisms that govern the morphology and connective processes of nerve cells, he developed a revolutionary new theory that came to be called the "neuron doctrine", based on the fact that brain tissue is composed of individual cells. A humanist, as well as a scientist, he is considered the head of the so-called Generation of Wise Men. He is frequently cited as the father of neuroscience.

Name

The name he himself used was sometimes "Santiago Ramón Cajal" but other times Sometimes, for example in his book Recuerdos de mi vida , he used "Santiago Ramón y Cajal", adding "y" between the two surnames. This way of naming has a tradition in Aragon and avoids misunderstandings, since his first surname is also a given name. In many foreign circles he is referred to only by his second surname, "Cajal". His middle given name was Felipe , and his full name was therefore Santiago Felipe Ramón Cajal .

Childhood and youth

He was born in Petilla de Aragón, —a Navarrese enclave located in the province of Zaragoza—, the son of Antonia Cajal and Justo Ramón Casasús, both from Larrés. He lived his childhood between continuous changes of residence through different Aragonese towns, accompanying his father, who was a surgeon; Thus, when he was barely two years old, the family left Petilla de Aragón to move to Larrés, his father's town, and from there to Luna (1855), Valpalmas (1856) and Ayerbe (1860).

He completed his primary studies with the Piarists of Jaca and the high school in Huesca at a time marked by social unrest, the exile of Elizabeth II and the First Republic, proclaimed just as he was finishing his high school studies in Huesca. According to his own biographical accounts, Ramón y Cajal showed, from a young age, a vocation for the plastic arts, especially drawing; He also comments in them on his life as a student, his mischievous nature and his refusal to memorize on the run, two circumstances that earned him the enmity of the friars who taught him, in a tradition of violent and authoritarian methods (the letter with blood enters). In that period he began his love for the mountains, and his proverbial defense of a healthy life in contact with nature.

Adult life and professional career

He studied Medicine in Zaragoza, where his entire family moved in 1870. Ramón y Cajal focused on his university studies with success and, after graduating in Medicine in June 1873, at the age of twenty-one, he was called to ranks in the so-called Quinta de Castelar, the military service ordered by the famous politician, president at that time of the ephemeral First Republic.

Doctor in the Cuban war (1873-1875)

The first months in the militia were spent in Zaragoza, and soon after, competitive examinations were held for the Military Health Corps, in which, out of a hundred candidates for thirty-two positions, he obtained no. 6. He is assigned as & #39;second doctor' (lieutenant) to the Burgos regiment, quartered in Lleida, with the mission of defending the Llanos de Urgell from the attacks of the Carlists.

During that time, Cuba, still a Spanish province, was waging a war for its independence, known as the Ten Years' War. In 1874 Ramón y Cajal marched to Cuba with the rank of captain, since the passage to Overseas entailed promotion to immediate military employment.

Ramón y Cajal was attracted by the wonderful parks and gardens of Havana, as well as by tropical flora in general, as he had been fascinated by it in his readings. It takes a short time to verify, however, that the admired and dreamed jungle was unbearable for Europeans. The absence of the exuberant fauna and flora that he had imagined, plus the omnipresent mosquitoes, spreaders of the dreaded malaria, managed to completely undo the romantic and adventurous ideal of the island that Ramón y Cajal had formed.

His father had obtained for him, so that he had a more favorable destination, some letters of recommendation, which he refused to use; Perhaps this influenced his being sent to the worst possible medical destination: the Vistahermosa infirmary, in the province of Camagüey, in the middle of the swampy jungle. An insufficient facility to accommodate the large number of soldiers sick with malaria and dysentery. Very soon the young doctor fell ill and, after a first convalescence in Puerto Príncipe, he was transferred to the San Isidro infirmary, even more unsanitary than the one in Vistahermosa.

The experiences with the administrative and military system lived by Ramón y Cajal in this overseas ranch were as bitter for him as the diseases contracted there. He had to face administrative chaos, the incapacity and immorality of certain rulers and some army commanders, from the post commander to the cooks and part of the detachment officers, who had the habit of stealing food and resources for themselves. missing the sick and wounded. Bitter experiences that led him to request a license to leave Cuba, attended on May 30, 1875 after being diagnosed with "serious malarial cachexia" and declared "disabled in the campaign." He arrived in Spain in June 1875 through the port of Santander, Cantabria, turned into a human ruin, in no way reminiscent of the vigorous and athletic young man who had arrived in Cuba a year earlier ».

In order to recover half of his back pay, he had to bribe the official on duty because, otherwise, they threatened to delay indefinitely. However, «it is worth noting here that part of the savings from his stay in Cuba were the financial bases that allowed Ramón y Cajal to acquire the microscope, a microtome, chemical reagents and dyes with which he set up a modest laboratory on his return in the that would initiate the histological investigations». His return to Spain and the care lavished on him by his mother and sisters gradually restored Santiago Ramón y Cajal to his health and allowed him to resume his academic career, already on his way to teaching (1876) and doctorate (1876-1877).

Beginnings of his research vocation

The year 1875 also marked the beginning of his doctorate and his scientific vocation. Santiago bought his first microscope before winning, in 1876, a position as assistant guards, he also took private patients from his father's surgery, at the Hospital Nuestra Señora de Gracia in Zaragoza.

He received his doctorate on June 26, 1877, at the age of twenty-five, with the thesis entitled Pathogenesis of inflammation, at the Central University, now the Complutense University of Madrid.

In 1877, his entry into the Masonic Knights of the Night lodge, belonging to the Lusitanian Grand Orient, is also documented, with member number 96 and the symbolic name of Averroes, the Andalusian doctor.

In these years, a time of ups and downs began for Ramón y Cajal, with a terrible 1878, marked by tuberculosis, and an 1879 of achievements, obtaining the position of Director of the Anatomical Museums of Zaragoza and his wedding on July 19, for love and against the opinion of his parents and friends, with Silveria Fañanás García, with whom, over fifty-one years of quiet and collaborative coexistence, he would have seven children: Santiago, Felina (Fe), Pabla Vicenta, Jorge, Enriqueta, María del Pilar and Luis, two of whom (Santiago and Enriqueta) died before him.

He won the chair of Descriptive Anatomy at the Valencia School of Medicine in 1882, where he was able to study the cholera epidemic that struck the city in 1885.

Discovery of neurons

In 1887, he moved to Barcelona to occupy the chair of Histology created at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Barcelona. It was in 1888, defined by himself as his "peak year", when he discovered the mechanisms that govern the morphology and connective processes of the nerve cells of the gray matter of the cerebrospinal nervous system.

In May 1888, he published in the Quarterly Review of Normal and Pathological Histology that brain tissues were not made up of continuous connections as was believed to date given the research of Camillo Golgi, that although they allowed to see the nerves and the cerebral tissues, their precision did not allow to show the neurons.

His theory was accepted in 1889 at the Congress of the German Anatomical Society, held in Berlin.

In 1891, Wilhelm Waldeyer was the first to state the neural principle, reviewed the anatomy of the nerve cell, and coined the word neuron. The first paper containing a principle that was later elevated to the level of doctrine and placing neurons as the elementary unit of the nervous system was published by Waldeyer on December 10, 1891.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal's structural scheme of the nervous system as an agglomerate of independent and defined units came to be known as the «neuron doctrine», and in it he highlights the law of dynamic polarization, a model capable of explain the unidirectional transmission of the nerve impulse.

In 1892 he held the chair of Normal Histology and Histochemistry and Pathological Anatomy at the Central University of Madrid. He managed to get the government to create a modern Biological Research Laboratory in 1901, where he worked until 1922, the year he retired and when he went on to continue his work at the Cajal Institute, named after him, where he would maintain his scientific work until his death.

Between 1897 and 1904 he published, in the form of fascicles, his magnum opus Histology of the nervous system of man and vertebrates.

Thanks to Ramón y Cajal's detailed histological examinations, the synaptic cleft was discovered, a space between 20 and 40 nanometers that separates neurons; This space suggested communication through chemical messengers that crossed the cleft and allowed communication between neurons, studies continued by the English physiologist Henry Hallett Dale who discovered the first neurotransmitter, acetylcholine, thus laying the foundations for understanding how both level of the central nervous system as well as the peripheral nervous system of the majority of existing drugs and those that would be developed later.

He proposed the existence of dendritic spines, a small bulge in the membrane of the dendritic tree of certain neurons where, typically, synapses occur with an axonal knob of another neuron, and sometimes several axons contact. Proof of this only came after electron microscopy was developed during the second decade of the XX century.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal also discovered the neural growth cone, a conical expansion of the distal end of developing axons and dendrites, first described by him, which constitutes the extension of a developing axon to achieve proper synaptic connection throughout the nervous system.

After creating excellent descriptions of neural structures and their connectivity, and providing detailed descriptions of cell types, he discovered a new cell type, the interstitial cell of Cajal (ICC). These cells are interspersed among neurons embedded within the smooth muscles lining the intestine, serving as a generator and pacemaker for the slow waves of contraction that move material along the gastrointestinal tract, mediating neurotransmission from motor neurons to the gut. soft smooth muscle cells.

Awards and distinctions in life

After his return from the congress in Berlin, he received many other triumphs and invitations, from the Moscow International Prize (granted during the XIII International Congress of Medicine in Paris in 1900), to the Helmholtz Medal (1905), through honorary doctorate appointments from Clark, Boston, Sorbonne, and Cambridge Universities in 1899, the same year in which he published the third fascicle of his Texture of the Nervous System of Man and Vertebrates, which would be completed in 1900 and 1901 and whose French translation greatly contributed to its international knowledge. After the awarding of the Moscow Prize, and responding in part to a general outcry among citizens and the press, the Spanish government, as As already mentioned, he would create the Biological Research Laboratory for him, which gave rise to the Spanish School of Neurohistology, one of the most important scientific centers in the country.

His medals and awards also include, chronologically, the Fauvelle Prize (April 18, 1896), awarded by the Société de Biologie of Paris; Rubio Prize (1897), awarded by the Royal Academy of Madrid for his Histology Manual, the grand-cross of the Civil Order of Alfonso XII (June 20, 1900) and the grand-cross of the Royal Order of Isabel la Católica (February 28, 1901), the Martínez y Molina Prize (January 25, 1902, 4,000 pesetas, awarded together with his brother Pedro for the work Sensory centers in the man and animals), the French National Order of the Legion of Honor with the rank of Commander (1914), the Cross of the German imperial order «Pour le mérite» (1915), the Echegaray Medal, granted by the Royal Academy of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences (May 7, 1922), in 1922 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the National Autonomous University of Mexico and the Plus Ultra Medal (April of 1926).

He was appointed senator for life in 1908.

The Nobel Prize

His work and contributions to neuroscience —disseminated in Europe by his friend the Swiss anatomist Rudolph Albert von Kölliker— were recognized in 1906 with the award of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, an award he shared with the Italian researcher Camillo Golgi, whose staining method was applied by Ramón y Cajal for years, but with whose theses, curiously, he did not and never agreed.

On what that first Spanish Nobel Prize in Sciences meant, two opinions can be compared, that of Ortega y Gasset who thought that the case of Ramón y Cajal was a shame for Spain, instead of a source of pride, because it was an exception. Years later, Severo Ochoa, another Nobel laureate, concluded that research in biology and medicine in Spain was poor, but without Ramón y Cajal it would have been nil.

After the Nobel Prize, Ramón y Cajal published some biographical works, in addition to his Studies on the degeneration and regeneration of the nervous system (Madrid, 1913-1914). His last scientific article, a sum of his ideas, was Neuronism or reticularism?: The objective proofs of the anatomical unity of nerve cells. It had been commissioned by a German journal, but the four years The delay in receiving the proofs from Germany made Ramón y Cajal fear that he would die before correcting it and seeing it printed, as it did. Without waiting for the Germans' response, the scientist proceeded to lighten his text and publish it in Spain.This scientific sum also appeared in French and, already posthumously, in Germany (1935). Later, in 1954, and on the occasion of the first centenary of the birth of its founder, there was an edition prepared by the Cajal Institute.

Last years

Don Santiago retired on October 11, 1922. The University of Zaragoza, where he studied Medicine, had commissioned a sculpture of the Spanish Nobel Prize winner from the Valencian sculptor Mariano Benlliure, with the idea of installing it in the Faculty of Medicine coinciding with with the beginning of the academic year 1922-1923. However, the carving of the sculpture was not ready for that day, and the homage was held in front of a provisional plaster copy.

Benlliure concluded his work in 1923, but the solemn inauguration did not take place until February 26, 1925. That day King Alfonso XIII arrived by train in Zaragoza, who personally unveiled the statue. It is located on the steps of the Auditorium, where the seated figure of the wise man, sculpted in white marble, life-size, dressed in the professor's robe and with his noble head uncovered, rests his left hand on a book.

The following year, 1926, a second monument to Santiago Ramón y Cajal would also be inaugurated by Alfonso XIII, the work of Victorio Macho's chisel, this time outdoors and in Madrid, on Paseo de Venezuela in Retiro Park.

In August 1930, the death of his wife from tuberculosis was a major blow for Ramón y Cajal. Despite this, in his later years he continued to work, preparing publications and reissues, and devoted himself to his students. Several of them (especially his favorite disciple since 1905, Jorge Francisco Tello, who had succeeded him in his chair and in the direction of the Institute), at the express wish of Ramón y Cajal himself accompanied him on his death, on October 17, 1934, after the aggravation of an intestinal ailment that weakened his heart. Very soon after, his autobiography The world seen at eighty years old , which he had finished and corrected shortly before, would be published. His remains rest, along with those of his wife, in the Almudena cemetery in Madrid.

On the table, next to the bed, there was a calendar opened by the date of the day: October 17, 1934. Fe Ramón Fañanás took the pen there abandoned by his father and wrote: "This day, at 11 minutes of the night, my father died."

Legacies

Santiago Ramón y Cajal and his wife left four legacies of 25,000 pesetas each, with the proceeds of which four prizes would be awarded, two annually (to the best Anatomy student at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Zaragoza and to the best student of Histology and Pathological Anatomy of the Faculty of Medicine of Madrid) and two biennials (one for the best published report on Pathological Anatomy, Histology or Bacteriology and another for the best published work on Comparative Psychology in any group of animals or of a species determined).

The honesty of Ramón y Cajal

"Let us love the homeland, even though it is nothing but for its deserved misfortunes. » |

In addition to his virtues as a scientist and human personality, Ramón y Cajal was an unusual example of honesty and well-understood patriotism. Here are three examples:

- Named director of the Biological Research Laboratory, the Government assigned him a salary of ten thousand pesetas a year. Ramon and Cajal asked him to be taken down to six thousand.

- He rejected the position of Minister of Health and Public Instruction, and if he accepted the appointment of a vital senator proposed by Canalejas, it was because he was free (he had no economic allocation).

- As president of the JAE, he sent his son Jorge, a researcher like him abroad, paying the expenses of his pocket. Asked about why he had not been pensioned with a scholarship, as usual, and more being his son, Ramon and Cajal replied: "That's why he was my son."

Poshumous awards

In 1954, histologists from the University of Medical Sciences of Havana, in Cuba, discovered a tombstone in the histology laboratories of the ICBP Victoria de Girón, along with other activities on the occasion of the centenary of Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

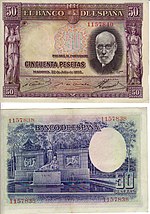

On April 1, 1952, on the occasion of the tributes for the first centenary of his birth, the dictatorship of Francisco Franco (disregarding the fact that Ramón y Cajal was a declared Freemason), granted him, posthumously, the title of I Marquis of Ramón y Cajal.

In 1973, the International Astronomical Union named the lunar crater Cajal in his memory. Likewise, the asteroid (117413) Ramonycajal bears this name in his memory.

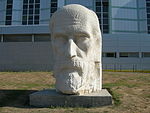

In October 1977, the Ramón y Cajal University Hospital was inaugurated in Madrid, in whose gardens a monumental head, the work of Eduardo Carretero, was installed.

On October 22, 1984, in the presence of his daughter María de los Ángeles and during the days when Enrique Tierno Galván was mayor of Madrid, a plaque commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Santiago Ramón y Cajal was unveiled, in the façade of the house located at number 64 calle de Alfonso XII, where the scientist had lived for the last twenty-two years of his life in Madrid, since 1909.

In 2002 the Diputación General de Aragón celebrated the 150th anniversary of his birth with different events, conferences, routes, a traveling exhibition, etc. Perhaps the most important event of the so-called "Año Cajal" It was the Great Cajal Congress, held in Zaragoza from October 1 to 3, 2003, with the assistance of renowned national and international scientists. Also in Zaragoza, the Ramón y Cajal Specialty Medical Center was named after him.

In 2009, on the 75th anniversary of his death, Radio Nacional de España brought together several minutes of sound recordings by Santiago Ramón y Cajal; in one of which he talks about neurons and their inability to multiply.

On December 10, 2011, the Santiago Ramón y Cajal Honorary and Multidisciplinary Chair was created at the University of Medical Sciences in Havana.

In 2019, the Madrid College of Physicians announces that it will dedicate 1,500 square meters to the creation of a Ramón y Cajal Chair Museum. However, he does not confirm if he will have his file.

Every year, the "Ramón y Cajal" The Ministry of Science of Spain offers some 200 contracts for the incorporation of doctors into the Spanish university system after a rigorous merit competition.

Correspondence from Santiago Ramón y Cajal

On December 6, 2014, the Spanish newspaper El País published the news that, when carrying out the necessary investigations for the edition of the epistolary of the Spanish scientist, the author of that work, Juan Antonio Fernández Santarén, discovered that a total of approximately twelve thousand documents were lost (sold, the majority) after they had been surreptitiously extracted from the Cajal Institute of the CSIC.

As a teacher

His autobiographical books and the biographies of those who knew him agree that there was perhaps only one job matched to his will as a researcher, that of a teacher. His students, who with his affection and guidance became new scholars and successors of his work, were the second family of Ramón y Cajal. His was a mixed philosophy of pedagogy, patriotism and tenacity:

Spain will not achieve its full cultural and political blossoming while teachers of all grades do not succeed in producing, in sufficient quantity, the Spanish that we do much need, that is, a human type so impersonal for selfless, so firm and whole of character, so tolerant and open to all ideas, so hard and constant in its endeavours, so acutely sensitive to our misfortunes that, reacting sharply to the causes of

As a writer

- Rules and advice on scientific research, published in 1897 and one of the most widespread of the scientist. Subtitle The Tonics of WillIt was translated into German (1933), Japanese (1958), Hungarian, Portuguese and English (1951) and Romanian (1967). It can be read from counsels for the choice of wife proper to a young researcher to sentences like this: "For scientific work the media are almost nothing and man is almost everything."

- Memories of my life, literary autobiography, which was published in loose chapters in the Revista de Aragón, between 1901-1904, and served as a basis for the subsequent editions of his collection of autobiographical texts.

- Holiday stories, subtitles Pseudo-scientific Narrations and published for the first time in 1905. The book is composed of five stories titled: "A secret aggrieved, secret revenge", "The maker of honesty", "The cursed house", "The pessimist corrected" and "The natural man and the artificial man".

- Psychology of Don Quixote and Quixotism, brief literary essay he wrote as a speech at the Faculty of Medicine of San Carlos on March 9, 1905.

- Coffee Talks (thinking, anecdotes and confessions), published in 1920 as Coffee cradles, a book of maxims and aphorisms, very popular as demonstrated by the ten editions that it had already reached in 1978.

- The world seen at eighty years (subtitles Impresiones de un arterioesclerotic), the last literary work of Ramón y Cajal, conclusa in 1934, shortly before his death. It is distributed in three parts: "Delirium of speed", "Degeneration of art" and "Consuelos de la senectud".

As a photographer

The first news that exists about Santiago Ramón y Cajal in relation to the optical foundation of photography occurs when, as a child, he is punished by being locked up in class at his school in Ayerbe. In the darkened classroom, he discovered that the light that enters through a crack in the shutter projects on the ceiling, upside down and with its natural colors, the image of the people passing by outside (following the effect of the camera obscura); This observation did not go unnoticed, being later described in his memoirs Memories of my life. My childhood and youth.

Ramón y Cajal was eighteen years old the first time he witnessed the miracle of silver bromide; It happened in Huesca, seeing some traveling photographers photographing the vaults of the church of Santa Teresa. His hobby and his research on innovative photographic techniques led him to manufacture plates in 1878 that only needed three seconds (instead of the usual three minutes for wet collodion plates) and improved the sensitivity of snapshots. The test report of him in a bullfight was a success in the professional media of Zaragoza; but no partner emerged to capitalize on the invention and his industry, and when he decided to develop it himself, news reached him that Edison had just patented a device based on the same principles.

Another invention by Ramón y Cajal, based on photographic emulsion techniques, was the improvement of Thomas Alva Edison's gramophone (or phonograph), which, despite improvements by Italian Gianni Bettini, did not reproduce the voice well. The restless Spanish researcher devised the recording of sound waves in a flat sense, tracing a concentric line on a glass or metal disc, covered with wax, which improved the timbre of the voice and amplified it. But he couldn't find a precision mechanic who would understand his idea and build the metal disc, so the scientist abandoned the project.

In 1890, Santiago Ramón y Cajal was named honorary president of the Royal Photographic Society of Madrid, and in 1912 he published the book Color photography, scientific bases and practical rules, warning about the future of chromatic (color) photography. Hundreds of stereoscopic photographs impressed on glass plates are preserved.

Disciples

Although the Civil War dispersed most of his collaborators, many of them subjected to ideological purification and dismissed such as Jorge Francisco Tello (1880-1958) when chairs were distributed more for political than scientific merits, some managed to continue their work abroad or barely inside. Nicolás Achúcarro (1880-1918) developed an important method of staining neurons and made contributions to the study of various nervous pathologies. Pío del Río Hortega (1882-1945) discovered microglia, the cells of nervous tissue that fulfill various auxiliary functions in the central nervous system. Fernando de Castro Rodríguez (1896-1967) carried out work that, although lately recognized, laid the foundation for numerous studies on the ultimate mechanisms of chemoreceptors that he himself had discovered, and Rafael Lorente de No (1902-1990) was one of the leading neurophysiologists in the world.

Contenido relacionado

Geronimo

Homeopathy

Immune system