Sanskrit

Sanskrit (autoglottonymous संस्कृतम् saṃskṛtam) is the classical language of India, as well as one of the oldest documented Indo-European languages, after Hittite and Mycenaean Greek. Sanskrit belongs to the Indo-European subfamily of Indo-Iranian languages and specifically Indo-Aryan.

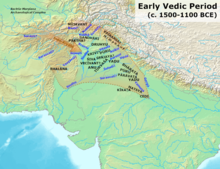

The oldest language of the Indo-Aryan branch, Vedic Sanskrit (or ritual language of the Vedic religion), is one of the oldest members of the Indo-European family. Its oldest known text is the Rigveda, composed and consolidated between 1500 and 1000 BCE. C., in the early part of the Vedic period.

In the second part of the Vedic period, a rigorous and sophisticated tradition of linguistic analysis developed, especially with regard to phonetics and grammar, in an attempt to stop the change of language, as Vedic literature was gradually becoming difficult. to recite and understand. This tradition culminated in Pāṇini's Aṣṭādhyāyī, which is the starting point of classical Sanskrit. In fact, the name 'saṃskṛta' literally means 'perfected, refined': sam: 'com-, completely'; kṛtá: ‘fact, work’ (from the root √kṛ-).

Sanskrit is the language of philosophy and scientific studies in classical India, and is currently used as a liturgical language in Hindu rites, in the form of hymns and mantras. It is also the language of Buddhism and Jainism. Today it is one of the twenty-two official languages of India, used for private purposes and to a lesser extent as a language of culture. The position of Sanskrit in the culture of India and Southeast Asia is similar to that of Latin and Hellenistic Greek in Europe.

Most of the surviving Sanskrit texts were transmitted orally (with mnemonic meter and rhythm) for several centuries, until they were written down in medieval India.

Historical, social and cultural aspects

History and development

According to scholarly studies and analysis of archaeological, linguistic, and genetic data, the arrival of the Indo-Aryans in multiple waves in India occurred in the first centuries of the 2nd millennium BCE. C. In this period, the Indus Valley civilization was already in decline.

After the mixing of the Indo-Aryans with the indigenous population, the Indo-Aryan language form rapidly evolved to the point of the Vedic period. Thus we have a history of three millennia of Sanskrit literature.

The introduction of Pāṇini's Aṣṭādhāyī, a generative grammar with algebraic rules of linguistic structure, as the culmination of a great grammatical tradition of many centuries, brought about a stabilization of formal language as the official definition of 'Sanskrit', while the natural and colloquial languages of the Prakrits continued to evolve into the present-day languages of India.

With this divergence of the natural languages from the official standard, the importance of Sanskrit as a vehicle of communication between the Indian nations increased and made possible the unity of all of them. Not only the Brahmanical elites, but also Buddhists and Jains participated in this phenomenon: for example, Aśvaghoṣa (2nd century) is a very important figure both in the history of classical Sanskrit literature and for Buddhism.

Another example is that the two great epic texts, the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata, were not recited and propagated by Brahmins, but by sūtas. Although the nuclei of the two works are very old, the final versions of the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata stabilized in the first centuries of our era, and their language is Sanskrit, not exactly Pāṇinian, but Sanskrit nonetheless.

With Aśvaghoṣa begins a great period in Sanskrit literature that lasted for about a millennium. But the best known and most celebrated figure in classical literature is Kālidāsa, called the Shakespeare of India by modern critics such as Sir William Jones and Monier Williams.

Written in the fifth century, Kālidāsa's works represent the culmination of a great literary tradition, but, like Pāṇini, Kālidāsa also eclipsed his predecessors, with the result that their works were not preserved. In Kālidāsa's and similar works, while Brahmins and other high-caste people speak Sanskrit, low-caste ones, as well as women and children, speak Prakrit languages.

Sanskrit is not exactly a dead language, as some tens of thousands in India claim to have it as their usual lingua franca in certain contexts. In fact, reading and writing is still taught in schools and homes throughout India today, albeit as a second language. And some Brahmins come to consider it their 'mother tongue'. According to up-to-date reports, it is being revived as a local language in the village of Mattur, near Shimoga, Karnataka. However, most people who speak Sanskrit fluently acquired it as a second language rather than as a language. their first language.

Archaism

The archaism of Sanskrit, particularly in the consonantal system, is appreciated when compared with other ancient languages, such as Latin, Greek, or even modern languages that retain a good number of archaisms, such as Lithuanian. Although all of these languages have undergone considerable phonetic and grammatical changes that have moved their structure away from that of Classical Proto-Indo-European, they do retain some notable similarities. J. P. Mallory uses a Lithuanian proverb (written in Sanskrit, Lithuanian, and Latin) to show the close resemblance:

- Sanskrit: «Devas adadāt datás, Devas dat dhānās».

- Lithuanian: «Dievas davė dantis, Dievas duos duonos».

- Latin: "Deus dedit dentes, Deus dabit panem".

- Spanish: "God gave us teeth, God will give us bread."

Classification

Sanskrit, like the other Indo-Aryan languages, is closely related to the Iranian languages, which is why it is referred to as the Indo-Iranian or Indo-Aryan branch of languages. Vedic Sanskrit is closely related to the Avestan language of the Zoroastrian religion, to such an extent that, with the help of a handful of phonetic rules, a text can be faithfully converted from one language to the other, which can be demonstrated with this example:

| Avéstico | t am amanvant ym yazatmm | sūr sm dāmōhu s svištmm | miθr ym yazāi zaoθrābyō |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vedic | tám amanvantam yajatám | śūraram dhā 'masu śávi udoham | mitrám yajāi hótrābhyaḥ |

| Protoindoiranio | ♪ you amanvantam already ♪ | *ćūraram dhā`masu ćávištham | *mitrám yăi jháutrābhyas |

Sanskrit is also closely related to the Balto-Slavic languages, also satem languages, such as Russian and Lithuanian in aspects of nominal inflection, pronouns and adverbs, etc. There is a large amount of vocabulary not shared with other Indo-European subfamilies.

Sanskrit is considered in some respects a conservative language, reflecting particularly well some features of later Proto-Indo-European, and an ancestor of the modern Indo-Aryan languages of India.

Other Indo-Aryan languages chronologically later than Sanskrit are the Prakrit languages, in one form of which the Buddhist canon was drawn up, followed by the 'corrupt' apabhraṃśas, and in the latest generation contemporary languages.

For a long time, Sanskrit was considered to be the origin of those languages. But current evidence suggests that Sanskrit is not the direct ancestor or "mother tongue" of the modern Indo-Aryan languages, but rather a parallel branch (a kind of "maternal aunt" to the more modern languages, if you will). Most modern languages would derive from some form of local Prakrit.

The same is true of the Romance languages, which do not exactly originate from the Classical Latin of Cicero and Caesar.

Geographic distribution

The historical presence of Sanskrit is widely demonstrated in many regions of Asia. Inscriptions and literary evidence suggest that Sanskrit was already adopted in Southeast and Central Asia by the first millennium.

Significant collections of Sanskrit manuscripts and inscriptions have been found in China and Tibet, Burma, Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia. Sanskrit inscriptions or manuscripts have also been discovered, including from very ancient texts, in deserts and mountainous regions of Nepal, Tibet, Afghanistan, Mongolia, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan, as well as Korea and Japan.

Phonology

The Sanskrit alphabet or sound system can be represented in a two-dimensional matrix according to the articulatory criteria:

| deaf | sound | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| open | ḥ | h | a | ā | |||||||

| monitoring | k | kh | g | gh | |||||||

| palatals | ś | c | ch | j | jh | ñ | and | i | ī | ē | ai |

| backsliding | . | Δ | ṭh | roga | rogah | . | r | . | |||

| dental | s | t | th | d | dh | n | l | ||||

| the lips | p | ph | b | bh | m | v | u | ū | or | au | |

| friction | inspired | aspirated | inasp | asp | nasal | semi-volic | shorts | long | |||

| Ploss | simple | diptongos | |||||||||

| vocalists | |||||||||||

| consonant | vowels | ||||||||||

The traditional alphabetical order is the vowels, the diphthongs, the anusvara and the visarga, the plosives and the nasals, and finally the liquids or semivocalics and fricatives.

Grammar

Sanskrit, like other ancient Indo-European languages of the 1st millennium BCE. C., is an inflectional and synthetic language, with SOV and prepositional dominant basic order (although there are a few postpositional elements).

Nouns and adjectives can distinguish up to eight morphological cases (nominative, vocative, accusative, genitive, dative, ablative, locative, and instrumental), three numbers (singular, dual, and plural), and three genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter).. The verb has practically the same inflectional categories as ancient Greek.

Writing

Sanskrit and its earlier forms did not develop into a writing system. Before the arrival of the Aryans, writing existed in the urban civilization of the Indus, but their irruption caused its disappearance. Sanskrit is written from left to right.

There was no form of script during the development of Vedic literature in the Vedic period. Even after the introduction of writing, the works continued to be transmitted orally for centuries. The manuscripts of the Ṛg·veda, composed before 1000 BCE. C., did not appear until 1000 AD. C. Even when the diffusion of written works began in this way, oral transmission continued to predominate until very recently.

It is not known when writing developed in India or when it was introduced again, but the earliest records date from the 3rd century BCE. C. From this period there are inscriptions of Emperor Aśoka in the Brāhmī script, generally not in Sanskrit, but in the pracrits of each region. It has been shown that Brahmi was based on the Semitic script, but adapted to Indic phonology.

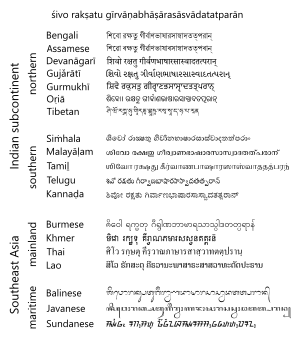

Brahmi is an abugida script in which each consonantal character also has a vowel element, ie the character is literally sonanted. The vast majority of writing systems in India, Southeast Asia, and elsewhere are derived from Brahmi, and in each region those scripts are used to write Sanskrit, both in Bengal and Thailand.

Since the 18th century, Sanskrit has also been written in a form of Latin script that is the International Sanskrit Alphabet.

Literature

Sanskrit literature can be broadly divided into works composed in Vedic Sanskrit and Late Classical Sanskrit.

Vedic Sanskrit is the language of the comprehensive liturgical works of the Vedic religion, which, in addition to the four Vedas, include the Brāhmaṇas and Sūtras.

The preserved Vedic literature is entirely religious in nature, while the classical Sanskrit works cover a wide variety of fields: epic, lyric, drama, romance, fables, grammar, civil and religious law, political science and practical life, science of love and sex, philosophy, medicine, astronomy, astrology, mathematics, etc. It is essentially secular in subject matter.

Vedic literature is basically optimistic in spirit, portraying man as strong and powerful, capable of attaining fulfillment here and in the afterworld. The later literature, on the other hand, is pessimistic. It shows human beings controlled by the forces of destiny, and the pleasures of this world as the cause of misery. These fundamental psychological differences are attributed to the absence of the doctrines of karma and reincarnation in the Vedic period, ideas prevalent in later eras.

Works

| Genre, collection | Examples | References |

|---|---|---|

| Scripture | Vedas, Upani wounds, agamas, the Bhagavad·Gītā | |

| Language, grammar | A calamariādhyāyī, Gaa·pātha, Pada·pātha, Vārttikas, Mahābhāssaya, Vākya·padīya, Phiṭ·sūtra | |

| Law, civil and religious | Dharma·sūtras/Dharma·śāstras, Manu·smieseti | |

| Political science | Artha·śāstra | |

| Logic, mathematics | Kalpa, Jyoti Sardinia, Gana·śāstra, Śulba·sūtras, Siddhāntas, Àryabhaṭīya, Daśa·gītikā·sutra, Siddhānta·śiromanui, Ganuita·sāra·sa,graha, Bīja·gana | |

| Medicine, health | Äyurveda, Suśruta·sa,hitā, Caraka·sa,hitā | |

| Sex, emotions | Kāma·sūtra, Pañca·sāyaka, Rati·rahasya, Rati·mañjari, Ana,ga·ranga | |

| Epopeya | Rāmāyana, Mahābhārata | |

| Epopeya del Corte (Kāvya) | Raghu·va,śa, Kumāra·sambhava | |

| Gnomic and didactic literature | Subhā Krishnaitas, Nīti·śataka, Bodhicary'âvatāra, Ś,gāra·jñāna·nirnuaya, Kalā·vilāsa, Catur·varga·sa,graha, Nīti·mañjari, Mugdh'ôpadeśa, Subhāna·ratna·sandoha, Yoga·śā | |

| Drama, dance, the arts | Nāṭya·śāstra | |

| Music | Sangīta·śāstra | |

| Poetry | Kāvya·śāstra | |

| Mythology | Purāna | |

| Philosophy | Darśana, Sā,khya, Yoga (philosophy), Nyāya, Vaiśerchika, Mīmā,sa, Vedānta | |

| Scripture, monastic law (budistica) | Tripiṭaka, Mahayana Buddhist texts, others | |

| Theology, philosophy (jainica) | Tattv'ârtha Sūtra, Mahāpurana and others |

Sanskrit and Spanish

Cognate words - of common Indo-European origin

Being languages of the same family (Indo-European), Spanish and Sanskrit share many similarities, characteristics inherited from the common parent, in the fields of grammar and lexicon. Here you can see some cognate words, that is, of the same Indo-European origin.

| Sanskrit | Spanish | Latin |

|---|---|---|

| me. | me. | me. |

| you | you | you |

| nas | us. | us. |

| Go. | You | You |

| sva- | ♪ | se, sui- |

| itara | Other | alter |

| antara | between | inter |

| upari | on | super |

| Tri | Three. | trēs |

| daśa- | Ten | dec·em |

| māt | mother | mate |

| dā- | da·r | da·re |

| ī- | go | I'll go. |

| ad- | eat | com·ed·ere |

| pib-, pā- | beb·er | bib·ere |

| jīv- | viv·ir | viv·ere |

| mANTE-, mANTE·ta- | mor·ir, morer·to | mor·tu- |

| deva·s | dio·s | deu·s |

| nava- | new | Novo- |

| ja-, jan- | people | gens |

| nakta- | night | Nox, noct- |

| aksu | eye | ocus |

| nāsa | nose | nasum |

| pad- | foot | pe(d)s |

| dant- | too | den(t)s |

| apas | work | opus |

| sakha- | partner | partner- |

| sad- | headquarters | sed- |

| vāc- | voice | Vox |

| dak zera | right. | dexter |

| hima- | hiemal | hiems |

| Rudra-, roh- | Red | Blond- |

| dharma- | firm | firmus |

| jihvā | tongue | lingua |

| mātra- | med·ir | Meat- |

| svapna- | dream | somnia ≥ sopnia |

Sanskrit Loan Words

Numerous words related to religious and cultural elements of India have names from ancient Sanskrit:

- asana (yoga position)

- autía or tutía (present in the saying "no tutía")

- avatar (ava-tara“that descends”

- ayurveda (aiurvedic medicine)

- gangna (bandhana, ‘atadura’

- bodhisattva

- brahman (priest)

- Buddha

- chakra (energy center)

- eka- (‘one’) to indicate the first unknown element under a known one, examples:eka(now called Scandio), «ekaluminum» (now called galio), etc.

- dvi- or dwi- (‘two’), to indicate the second unknown element under a known one; for example:dvi(called polonium since its discovery in 1898)

- guru (‘maestro’)

- swastika (his astika“very auspicious”

- karma

- Send it.

- mantra (canto)

- maia (velo ilusorio)

- nadi (energy channel)

- nirvana (éxtasis)

- Sanskrit

- shanti (peace)

- tri- (‘three’) to indicate the third unknown element under a known one; for example:Trimanganese" (called Renio since its discovery in 1925)

- yoga

Words derived directly from a Sanskrit term

- ario (aria)

- Brahmanism

- Buddhism

- in Sanskrit synjala: ‘with lions’

Words derived indirectly from a Sanskrit term

- chess (arabic loan, but of Sanskrit origin: chatur anga“four members”).

- alcanfor: Al (Arabic) + karpūrā: ‘Chemistry’

- añil (from Spanish Arab annihil or AnnírEast of classic Arabic nil[ağ]East Persian niland this of the Sanskrit nīla).

- sugar (from Spanish assúkkarEast of classic Arabic sukkarEast of the Greek σκαρι /sakhari/, east of the pelvi šakarand this of the Sanskrit shuklá: ‘white sugar’ or sukha ‘happiness, sweetness’).

- sulphur (Arabic Loan, Sanskrit śulbāri: ‘copper enemy’; being śulbā or śulva: ‘copper’; āri: ‘enemy’).

- blue (perhaps altering Hispanic Arabic) lazawárdEast of Arabic lāzawardEast Persian the United Nations or lažvardand this of the Sanskrit rajavarta, ‘lapizlázuli’).

- cost (Costus villosissimus): Weed of yellow flowers originating from India (from Latin Costus, this of the Greek κόστος, and this of the Sanskrit kusthahwhich means ‘bad parado’, being ku: ‘bad’, and stha: ‘is’.

- ginger (Latin zing, zingiběris, this of the Greek γγγγγερις, and this of the Sanskrit shringavera (singing) shringa: ‘near’ and Vera: ‘cuerpo’ or ‘boca’), although according to the RAE comes from the non-existent Sanskrit word singavera).

- lacquer (from the Spanish Arab lákkEast of Arabic lakkEast Persian lākand this of the Sanskrit lakshathat already appears in the Átharva-vedafrom the end of the second millennium to C.). Maybe he's related to it. Lakshá (the number 100 000), perhaps in reference to the large number of insects similar to the pigeon that with their bites make this type of tree exude this resinous substance, translucent, brittle and reddish.

- lacha: shame, pundonor Layy).

- lila (from French lilacEast of Arabic līlakEast Persian lilangand this of the Sanskrit Nila“dark blue”).

- Lime. He shares his etymology with the word "limon". Dermation of Hispanic Arab lima east of the Arabian līmah, east of the Persian لیمو /limú/, and east of the Sanskrit nimbú,

- lemon (from Spanish ♪ or Laimeast of the Arabian laymūnEast Persian limúand this of the Sanskrit nimbú, which actually referred to the ‘ acid lime’.

- orange (from Spanish NaranğaEast of Arabic nāranğEast Persian nārangand this of the Sanskrit narangawhich possibly comes from the Sanskrit nagá-ranga (‘the color of the town’, the orange tree). It also appears as nagáruka, nagá vriksha (‘the serpent’), Nagara (city, village) naringa, naringui and Narianga.

In popular culture

In the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), by Gabriel García Márquez (1927-2014), Aureliano Babilonia learns Sanskrit to understand the content of the manuscripts where Melquíades prophesied a century of history Of all the family.

In 1998 the singer Madonna recorded an album entitled Ray of light, strongly influenced by Hinduism, Kabbalah and other doctrines. One of the songs on the album is titled Shanti/Ashtangi, it contains verses from Yoga-taravali, as well as original verses, sung entirely in Sanskrit.

The theme «Duel of the fates», from the soundtrack of the first trilogy of the Star Wars saga (Episode I - The Phantom Menace, Episode II - Attack of the clones and Episode III - Revenge of the Sith), is sung in Sanskrit and is based on an ancient Celtic poem called "Cad Goddeu" ('The Battle of the Trees').

Glossary

Traditional glossary and notes

- ↑ śvāsa

- ↑ nāda

- ↑ Kazakh

- ↑ tālavya

- ↑ mūrdhanya

- ↑ dantya

- ↑ o calamity

- ↑ alpa·prāna

- ↑ mahā·prāna

- ↑ anunāsika

- ↑ antastha

- ↑ hrasva

- ↑ dīrgha

- ↑ sparśa

- ↑ svara

- ↑ vyañjana

Contenido relacionado

Transcription (linguistics)

Guatemalan languages

Princess of Asturias Award for Letters