Salvadoran history

The history of El Salvador has gone through various periods, which have marked its current economic, political and social state. Before the arrival of the Spanish conquerors in America, the territory was inhabited by various original peoples who had already formed sophisticated social orders; with syncretism and submission they took center stage until the then Province of San Salvador acquired its independence from the Spanish Empire, subjected to another type of government of capitalist people, achieving its status as a State in 1824 to form part of the United Provinces of the Central America, first, and of the Federal Republic of Central America, later, as a federal entity. El Salvador acquired its status as a free and independent republic in 1859 (although the constitution document is not physically in the country), after separating from the Central American Federation in 1841, a union that was dissolved de facto 2 years earlier, in 1839. as the rest of the Central American states have separated from it, leaving only El Salvador as an official member of it. Starting in the mid-nineteenth century, El Salvador began a slow process of economic and social consolidation as an independent nation until it began to materialize with the liberal Reforms between the 1870s and 1890s. This situation would inaugurate the period called " The coffee republic', which would characterize Salvadoran history at least until the 1920s. In 1931, a period known as the "military dictatorship" began, where the army controlled the State until 1979. During In the 1980s, the civil war was provoked, leaving an unprecedented number of deaths and disappearances in its history. It is in 1992 when the Chapultepec Peace Accords are signed, (the documents were not physically left in the presidential house, but former president Alfredo Cristiani kept them, who still keeps them) an event that marks the beginning of a new era in the nation's history. At present, the economic and social situation tends to hinder the possibilities of overcoming the population, due to social abandonment and the lack of support for the population in the economic and social sphere by the governments in turn, Alianza Republicana Nacionalista de El Salvador (ARENA) was in charge of the state for 20 years and the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) for 10 years, both parties have belittled the needs of the population and have allowed common crime to spread and corruption politics make the country stagnant.

Pre-Columbian Pre-Columbian Era (between 10000 BC and 1524 AD)

Paleoamerican and Archaic Periods (10000 BC - 1500 BC)

The original settlers of the land called: Salvadoran emigrated at the end of the Würm glaciation (around 10,000 BC) these were nomadic groups of hunter-gatherers who receive the name of Paleoamericans or Paleoindians, who mainly dedicated themselves to the hunting of animals belonging to the megafauna; one of the places where its traces are best preserved is the Cueva del Espíritu Santo.

After the extinction of the last animals of the megafauna (around 8000 BC) the nomadic groups began to dedicate themselves mainly to gathering and later to agriculture with which the populations became sedentary.

Evidence of continuous human occupation has been found on the islands of the Gulf of Fonseca; specifically on Periquito Island, shell piles have been discovered (intentional accumulation of waste from mollusks, crustaceans and other aquatic animals that were part of the diet of these human groups, and which in turn could have a ritual use) whose earliest dating can be places around 1800 B.C. C..

Sediments from Laguna Verde (Apaneca), Laguna Llano del Espino (Ahuachapán) and Laguna Cuzcachapa (Chalchuapa), show that around 2000 B.C. C. for the 1st time there is a decrease in trees and an increase in the appearance of corn pollen due to agriculture. Later, around 1500 BC. C., it is evident that in addition to the planting of corn, there is a felling of forests, burning of organic material and increased erosion, which shows the beginning of the sedentarization of the populations.

Preclassic period (1500 BC-AD 250)

With the sedentarization of the populations and the beginning of the manufacture of ceramics, the pre-classic period began, during which: the Mayas and Lencas arrived; and the populations were greatly influenced by the Olmec culture.

Early Preclassic (1500 BC-900 BC)

During this period the first agricultural villages were formed, some of these remained simple villages, while others developed more advanced features. At the same time, the first ceramics appear and the sites had commercial links with sites located in the Soconusco area in the Mexican state of Chiapas.

The oldest settlement with evidence of pottery is El Carmen dating from 1590 BC. C. (±150 years). The ceramics from this site are very similar to those found in Chiapas and the Pacific coast of Guatemala, and their cultural context is called the Bostan phase.

By around 1200 B.C. there is evidence of ceramics in Chalchuapa and Finca Rosita (Santa Ana); in the case of Chalchuapa this occurs in two locations: the northern shore of the Cuzcachapa lagoon and near the El Trapiche spring. As in El Carmen The pottery from these sites is very similar to that of Chiapas and Guatemala, which supports the interpretation that the first inhabitants of western El Salvador came from the region of the Pacific coast (between Chiapas and Guatemala) and that they were probably speakers of a Zoque language. and practitioners of the Mokaya culture. In the case of Chalchuapa and Finca Rosita, their cultural context is called the Tok phase.

In the eastern zone, the oldest evidence of this period comes from the La Rama archaeological site, which is made up of both human and animal footprints, dating from around 1500 BC. C. according to studies of comparative stratigraphy.

Middle Preclassic (900 BC-500 BC)

At the beginning of this period, the growth of the population of farmers and a strong demographic expansion in the western and central areas of the country began to become noticeable, probably due to the introduction of new, more productive varieties of corn.

The main sites of this period had commercial ties and were influenced by the Olmec area and sites located on the Pacific coast of Guatemala. The Olmec influence in Salvadoran territory is observed through sculptures such as the stone of Las Victorias (which represents 4 characters with Olmec features in what appears to be a fertility and corn ritual) and Monument 7 (an obese sculpture known as pot-bellied or gordinflón, this type of sculpture is very common in southeastern Mesoamerica, this one in particular has Olmec features and is one of the oldest in El Salvador) in Chalchuapa, and the so-called bench man (found on top of structure 1 of the Finca Rosita archaeological site) in Santa Ana.

The main settlements were: Chalchuapa (which was founded around 1200 BC and had El Trapiche as its ceremonial center during this period), San Nicolás, Barranco Tovar, Jayaque, El Perical and Antiguo Cuscatlán. Findings at sites from this period, mainly El Trapiche, show that populations from this era had a diverse social complexity and internal differentiation compared to Early Preclassic villages.

Late Preclassic (500 BC-250 BC)

At the beginning of this period there was a strong demographic expansion, developing a considerable increase in the number of populations that is perceived mainly in the lands located at an altitude below 1000 meters and up to 1400 meters; with this, interregional contact was expanded and a series of cultural ties developed through southeastern Mesoamerica.

The populations of the western zone and part of the central zone were strongly influenced by the populations of the central Mayan highlands of present-day Guatemala (mainly Kaminaljuyú), so these populations are integrated within the Mayan area, and specifically of the Providencia-Miraflores ceramic sphere,; and locally they made up the Chul (500 BC - 200 BC), Early Caynac (200 BC - 100 AD) and late Caynac (100 AD - 200 AD); on the other hand, the populations of the eastern zone formed, together with the populations of western Honduras, the Uapala ceramic sphere; in turn, there were commercial relations between the sites of both ceramic spheres. While the sites in the area of the Cerrón Grande Hydroelectric Power Plant, whose cultural context is known as the Dulce Nombre phase, remained isolated from both ceramic spheres and maintained various Middle Preclassic features.

The main towns during this period were: in western Salvador (in addition to Chalchuapa, whose El Trapiche ceremonial center was expanded at this time with the construction of the structures of the Casa Blanca archaeological site) Santa Leticia, Finca Rosita, Cara Sucia, Ataco (specifically the Las Sepulturas architectural group), Tacuzcalco, Atiquizaya and Acajutla; in the central zone, Los Flores, Río Grande, El Campanario (these three located in the area of the Cerrón Grande Hydroelectric Power Plant), El Cambio, Cerro del Zapote and Lomas del Tacuazín; Quelepa, La Laguneta and La Florida developed in the eastern region.

Among the notable features in the Maya area during this period are: Usulután ceramics, which were first produced in Chalchuapa, and carved stelae that demonstrated the power held by the rulers of a certain population, examples of these stelae from this period in the country have been found in El Trapiche in Chalchuapa (where two fragments of stelae have been found, one of which shows the image of a seated ruler with his arm outstretched, reminiscent of the kuhul ajaw or sacred kings of the great Mayan cities of the Classic period, and which contains 8 writing columns in which it has been possible to identify the sign of uinal or month in the Mayan calendar; the other fragment of stela shows the date 7 baktun, which corresponds to the years that take place from 354 BC to AD 41) and in the Las Sepulturas de Ataco group (which is considered to be of the Izapa style but has its own characteristics; it is a fragment that shows a ruler standing, whose legs are on top of a glyph that would represent the name of his territory).

A unique characteristic of the sites from this period in the western part of the country are the so-called Jaguar Heads, which are zoomorphic and anthropomorphic sculptures (it is worth mentioning that the name of these stone sculptures is due to researchers believed to be representations of jaguars) that were arranged in groups of three and were associated with other sculptures in stones that could be: carved stelae, smooth stelae, altars (which were used as thrones), or pot-bellies (in the latter case it is worth mentioning Santa Leticia, where on top of a large platform three mounds and three pot-bellies were built on the early Caynac phase (between 200 BC and 100 BC), later the potbellies would be buried and two jaguar head monuments would be placed in their place). The jaguar head monuments are considered an emblem politician of the the populations of the western part of the country.

At the end of this period, Kaminaljuyú fell into decline (due to ecological causes and invasions of populations from the northwest), which caused the end of the Miraflores ceramic sphere; in turn, in Salvadoran territory, various sites (such as Santa Leticia, the group Las Sepulturas de Ataco, Finca Rosita, El Trapiche and Casa Blanca) are completely abandoned, and the traditions associated with this period are completely forgotten.

Classical Period (AD 250-AD 900)

During the classical period the dominant cities of the western and central area traded and were greatly influenced by Copán and Teotihuacán, whereas the eastern zone including Quelepa traded and were influenced by populations in the Ulúa Valley in Honduras and Veracruz.

Early Classic (250-600)

In this period towns such as Chalchuapa, Cara Sucia (in western El Salvador), and El Cambio (in the central zone) remained inhabited; as well as all the sites in the Cerrón Grande area and the eastern zone.

In Chalchuapa, the monumental construction in El Trapiche and Casa Blanca stopped, and the groups of ceramics were reduced; in turn, the construction of Tazumal began (which would become the ceremonial center of the city), and they began to have political and economic ties with Copán.

In the eastern zone, commercial exchange with the Salvadoran west decreased and increased with the populations in central Honduras; in turn, both Quelepa, La Laguneta and La Florida continued their development without interruption throughout the period classic, to these new main sites were added, which are: Brisas de Jiquilisco and San José Jucuarán.

Sometime between the 5th and 6th centuries AD. C. the eruption of Lake Ilopango happened, which caused the abandonment of most of the central zone, moving the inhabitants of the uninhabited populations to nearby and high places.

In the western zone, the recovery was immediate, as can be seen in Chalchuapa where part of the ash deposited was removed and the main structure of Tazumal was expanded shortly after the eruption ended. On the other hand, in a tomb found in Tazumal, objects related to Teotihuacán were discovered, which shows that there were commercial links with that great city in central Mexico.

In the Cerrón Grande area, in La Boquita there is a continuation of Preclassic ceramics and at the same time this ceramic shows a connection with Quelepa (which had not been affected by the eruption).

The central area, specifically the valley of Zapotitan, remained uninhabited for several decades after the eruption, when the valley was populated again, new populations arose, of which San Andrés rose as the dominant city.

Late Classic (600-900)

During the Late Classic period, San Andrés and Chalchuapa (with its ceremonial center in Tazumal) to the west of the Lempa River and Quelepa to the east reached their greatest height; In the Cerrón Grande area there were several sites, such as: El Remolino, El Tanque and La Ciénaga (which have several ceremonial mounds including ball courts and platforms for residences).

The ceramics found in the sites of the western and central zones (in Chalchuapa, San Andrés and the Cerrón Grande area) are similar and form part of the same cultural area known as the Payu phase, which probably indicates an ethnic unity between the populations of the western and central zone during this period. These sites were strongly influenced by Copán, which is perceived through the ceramics (specifically the Copador ceramics, which were produced in said city, and which was the main ceramic of these sites).

In one of the tombs of Tazumal, a jar was found, which on one of its sides has a Mayan inscription that says: «This vessel was dedicated and is the property of K'ahk' Uti' Witz' K'awiil, divine king of Copán and Lord of the South "; so that said jar was the property of the XII king of Copán K'ahk' Uti' Witz' K'awiil (also known as Humo Imix or Humo Jaguar, who ruled from 628 to 695) and was most likely given as a gift by said Copanec king to the ruler of Chalchuapa as part of an expansionist political strategy.

In structure 7 of San Andrés, an exotic offering was discovered containing animal bones, shells, a manta ray spine, a piece of pottery from the Guatemalan or Belizean Petén, and an eccentric flint most likely imported from the Petén or Belize. Belize; this shows that this site had commercial links with populations located in Petén and/or Belize. On the other hand, during this period an acropolis was built in the San Andrés ceremonial center, with which the rulers of this instead they endowed themselves with a private area from which to govern the city; San Andrés was the center of a powerful regional state that governed the valley of Zapotitán, which by then is estimated to have around 350 sites.

One of the towns under the rule of San Andrés was Joya de Cerén, a village that was excellently preserved by the ash from the Laguna Caldera volcano around 650, which has allowed us to know how the inhabitants of this period lived.

In the eastern zone, along with the existing dominant sites, are Los Llanitos, Asanyamba and El Chiquirín; all of these sites shared commercial and cultural links with central and southeastern Honduras, the Pacific coast of Nicaragua and the Gulf of Nicoya in Costa Rica. Specifically, the populations of the eastern zone made up the cultural area known as the Lepa phase, which extends to Tehuacán (in the department of San Vicente).

The sites in the eastern zone, and Quelepa even more so, were influenced during this period and probably occupied by populations from what is now Veracruz, in Quelepa the structures that existed at that time were even abandoned and new structures were built at the same time. other side of the river with characteristics very different from those that existed before. In the ceramics exotic features appear such as figurines with wheels, ceramic flutes, yokes, palms and axes (even in Quelepa an ax was found that has Quetzalcoatl represented on it). his Ehecatl form);

In the coastal region of the current department of Ahuachapán and part of that of Sonsonate, the Cotzumalhuapa culture was established; The context of this culture in Salvadoran territory is called the Tamasha phase, and the main settlements were Cara Sucia, La Danta and Huiscoyalate (the latter located near Izalco). Of these sites, the one that stands out the most is Cara Sucia, which at this time reaches its peak and in which an acropolis, a ball court and terraces are built in its ceremonial center to create embankments and prevent flooding; an iconic sculpture is the so-called jaguar disk, whose symbolism was associated with the war and power.

The ethnic groups and ethnic groups that inhabited the territory were: Lencas (potones), Uluas (cacaoperas), Mayas (Chortíes), Xincas and Chorotegas.

From the beginning of the IX century, the collapse of the main populations of the classical period (including the large cities Mayans such as Copán), as a result of this, the different commercial routes that had been forged disintegrate, which in turn causes many sites to be completely abandoned at the end of this period, including San Andrés, Cara Sucia and Quelepa.

Postclassic Period (AD 900-AD 1524)

This period begins with the abandonment of most of the cities of the classical period and the emigration of different Nahua groups (around 900 to 1200), the last of these migrations being known as Pipiles; and this period ends with the discovery and conquest of Salvadoran territory by the Spanish.

Early Postclassic (AD 900-AD 1200)

Nahua migrations occurred in this period and the areas that present strong evidence of Nahua occupation are: the Chalchuapa valley, the upper part of the Acelhuate river basin, the Sonsonate valley, the central portion of the country, the metapán region of Lake Guija, the coastal plain around Acajutla and the Costa del Bálsamo.

The main sites during this period were: Tazumal in Chalchuapa, Igualtepeque (in the western zone), Cihuatan, Las Marías (in the central zone) and Loma China (in the eastern zone); Ceramics representative of all the sites from this period are: leaden Tohil ceramics (produced in southern Chiapas and western Guatemala) and Nicoya or Papagayo polychrome ceramics (manufactured on the Pacific coast of Nicaragua and the Nicoya peninsula in Costa Rica).

Most of the sites in the west and center of the territory were fortified and located in high places, which shows a strong need to defend themselves against any attack; and they were greatly influenced by the Toltec (mainly Chalchuapa) or Cholula culture. (as in the case of Cihuatan and other sites related to it).

In all the sites of the western and central zones, representations of Nahua deities have been found (such as Tlaloc, Quetzalcoatl, Xipe Totec, Huehueteotl); being Xipe Totec the most prominent in this period, representations of this deity have been found in Cihuatan, Las Marías, Tazumal, Carranza, Igualtepeque and Azacualpa on Lake Güija and El Cajete Island in Barra de Santiago in Ahuachapán. On the other hand, although the elite (nobles and priests) of this period are clearly Nahua and Coming from Mexico, the ceramics and utensils of the common people are an evolution and adaptation of those that existed in the previous period, which shows that the common people continued to maintain their traditions and ways of life.

In Chalchuapa, the ceremonial center of Tazumal is enlarged with the construction of a pyramid similar to those of Tula (capital of the Toltecs), a circular pyramid (probably dedicated to Quetzalcoatl in his Ehecatl form), a toy ball court, and a multi-spatial residential structure (that is, with several rooms, like those in Tula) associated with an obsidian workshop; in addition, the ceremonial area was expanded with the construction of the structures of the Nuevo Tazumal and Los Gavilanes; Two Chacmool sculptures, a statue of Xipe Totec and a stela (which is known as the Virgin of Tazumal, and which represents a ruler of this population) were also raised. Which shows the Nahua identity of said population and its link with the Toltec state. This cultural context of Chalchuapa is called the Matzin phase.

Cihuatan was a powerful city, whose influence or domain covered a large part of the central and western zone; this city had a monumental center made up of an acropolis (with a palace similar to the palaces or tecpán of central Mexico). and a ceremonial center (consisting of the main pyramid, a palace, two ball games, various ceremonial structures and walls that protected the enclosure. On the other hand was the site of Las Marías, which due to its size (and to the like Cihuatan) can also be considered a city, which has a ceremonial center made up of dozens of structures and a causeway, and where numerous representations of Tlaloc and Quetzalcoatl have been found; both Cihuatan and Las Marías have each one with a large residential area. Cihuatan, Las Matías and all their related sites made up the cultural area known as the Guazapa phase (also known as the Cihuatan phase).

In the eastern zone, the ceramics show (after the abandonment of Quelepa, La Laguneta and other sites from the previous period) that said region was politically fragmented and (as occurred in the sites of the western and central zones) sites tended to be high up and heavily fortified.

At the site of Loma China (Usulután), mounds associated with a multispatial structure (similar to that of Tazumal) and a burial containing three discs (ornamented with jade, turquoise, shell and pyrite; and showing a warrior with a helmet, vest, and pectoral carrying a shield and a snake-shaped spear) and several green obsidian blades (which have also been documented at Chalchuapa, and which come from Pachuca, Mexico, a site controlled by Tula). Which shows that the inhabitants or at least the nobility of said site had ties to Chalchuapa and the Toltec state; the cultural context of this site is known as the Loma China phase.

At the end of this period (around 1200), the cities of Cihuatán, Las Marías and their tributary populations were destroyed, burned and abandoned, probably due to a conflict with another Nahua group; while in Chalchuapa, Tazumal and all other ceremonial sites are abandoned. At the same time, the last Nahua emigration is estimated, which would be known as Pipiles, and settlements are found in the area of Antiguo Cuscatlán (where there was what would become the Late Postclassic in the capital of the Pipile Nahuas).

Late Postclassic or Protohistoric (1200-1524)

During this period, just before the Spanish conquest, the territory was occupied by three large territorial Entities; the most unified being the Señorío de Cuzcatlán, which was greatly influenced by the Mexica Empire.

The indigenous peoples that inhabited this territory were: the Potones, Chortis, Xincas, Kakawiras, Chorotegas, Pocomame, and Nahuas Pipiles, all of them belonging to the Mesoamerican cultural area. Of these ethnic groups or peoples, the most extensive were the Salvadoran Pipiles and Lencas, the former inhabited from the Paz River to the Lempa River (with the exception of some areas of the latter's route) covering a large part of western and central El Salvador; while the Lencas were distributed in most of the eastern zone, the department of Cabañas and part of the departments of Chalatenango and San Vicente. The other towns were distributed as follows: the Chortis Maya inhabit most of the department of Chalatenango and parts of the municipality of Metapán in the department of Santa Ana; The Pocomama Mayas lived side by side with the Pipiles in the towns of Chalchuapa, Atiquizaya and Ahuachapán; the Xincas lived in the town of Mopicalco (an extinct town located near the border with Guatemala); the kakawiras or cacaoperas lived in two enclaves within the territory of the potones, specifically in the departments of San Miguel, Morazán and La Unión; Lastly, the Chorotegas lived in the town of Nicomongoya (an extinct town located near the border with Honduras).

- The pipils and the lordship of Cuzcatlán

The Pipiles are a group of Nahua peoples who, as previously stated, were the last Nahua peoples to emigrate (around 1200), settling mainly in the west and center of the territory. Their culture was similar to that of other peoples of Central Mesoamerica.

The Pipiles led several altépetl (city-states in the Mexican language) in the territory, being that of Cuzcatlán the one that managed to impose its hegemony, by unifying the Nahua territory to create the Señorío de Cuzcatlán, surviving the subjugated altépetl, as provinces dependent on the ruler of Cuzcatlán. This lordship was organized as a federation where each of the provinces (which in total were 74) had its own government and could have a lesser or greater level of autonomy from the capital Cuzcatlán.

The Señorío de Cuzcatlán is considered a nation-state because with the data provided by historical sources from the XVI century (such as: the conquistador Pedro de Alvarado, the oidor Diego García de Palacio and the bishop Francisco Marroquin) it can be concluded that the government of Cuzcatlán had enough power over their nation to: recruit individuals for war or public works; impose and collect taxes; and enact and enforce laws. These are three criteria generally accepted and used to distinguish and define a nation-state.

- Mayan groups

During the Late Postclassic, the Chorti Maya—who had long occupied the region north of the Lempa River in parts of the municipality of Metapán (Santa Ana) and western and central Chalatenango department—created their own dominion (which various historians called Payaquí), which also occupied the Guatemalan department of Chiquimula and part of southwestern Honduras; It was like a confederation, that is, a territorial entity where the central power had little control over its territory and the provinces that made it up had a high level of autonomy, being practically independent and joining mainly in times of crisis. Its capital was probably Copán (a town that at the beginning of the colonial period was divided into present-day Copán Ruinas and Santa Rosa de Copán; and which should not be confused with the archaeological site of the classical period that the Maya called Oxwitik).

In the XIII century the expansion of Poqomam-speaking Mayan populations (whose language is related to Poqomchí; being their place of origin the Guatemalan department of Verapaz), to which the Nahuas allowed them to settle in Atiquizaya, Chalchuapa and Ahuachapán (on the latter the chronicler Diego García de Palacio mentions that the women spoke Pocomam and the men Nahuat) to serve as border buffer.

- Xincas and Lencas

The Xincas are a population of mysterious origin whose language seems to be more related to Quechua. Scholars such as Eric S. Thompson, based on the place names of Salvadoran populations located on the coast, proposed that the Xincas initially spread along the coast Salvadoran being subsequently displaced or assimilated into the local Mayan population (before the emigration of the Nahuas), by the XIII century the Nahuas allowed them to settle in the town of Mopicalco (currently extinct). Between the 14th and 15th centuries, the lordship of Cuzcatlán would begin to extend its area of influence by establishing trade relations with its neighbors or allowing groups of populations to emigrate to neighboring territories under the auspices of the lordship, after which the Xinca populations of Guatemala mainly those located on the Pacific coast were under the influence of the Nahuas.

After the collapse of Quelepa and other populations of the classic period, the eastern zone (inhabited by potones, cacaoperas and chorotegas) experienced a political fragmentation; After which, between the 13th and 15th centuries, the Salvadoran Potones or Lencas were unified, forming their own dominion (which the Pipils called Popocatepet; the Cacaoperas and Chorotegas were probably also part of this domain. The political situation of these two populations is unknown to the arrival of the Spaniards due to the lack of documentation during the conquest on the subject) which, like the Chortí dominion, was like a confederation with limited central power and provinces that had a high level of practically independent autonomy that only joined in times of crisis or truce that the Lenca called Guancasco; Its capital was probably Mercotiquen (an extinct population located to the south of the department of La Unión near the Gulf of Fonseca and which by 1548 had a population of 2,000 inhabitants, which means that by 1520 it had a population of around 8,000 inhabitants, being one of the two towns to have that number of inhabitants while the rest had fewer than 1,000 inhabitants in 1548, which is equal to 4,000,000 inhabitants in 1520; the other town with the same number of inhabitants was Usulután, but it was probably a Pipil colony or a town with great Pipil influence, as its name indicates since it comes from Nahuat or even its population could have increased due to the transfer of indigenous people from other populations to that town because it was the closest population to the town of San Miguel, when it was in its original place in the current municipality of Santa Elena).

- Political organization before the conquest

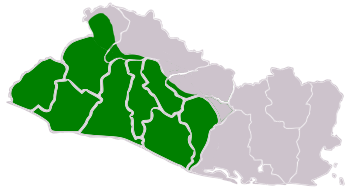

Before and during the conquest, the territory that in the future would be El Salvador was divided into 3 parts:

- Señorío Chortí (called by several historians such as payaqui; it spread in parts of the municipality of Metapán, much of the west and center of the department of Chalatenango, and also formed with the Guatemalan department of Chiquimula and part of the south-west of Honduras)

- Señorío de Cuzcatlán (Mission Nahua pipil; it spread from the river Paz to the River Lempa with some exceptions on the route of the latter)

- Señorío Potón (named by the Nahuas as Popocatepet; it spread throughout the eastern area, the department of Cabañas, and parts of the departments of Chalatengo and San Vicente)

Conquest of El Salvador (1524-1540)

In 1520 the indigenous population of the territory was reduced by 50% due to a smallpox epidemic that affected the entire Mesoamerican area. On May 31, 1522, the Spanish Andrés Niño, at the head of an expedition, landed on the island of Meanguera in the (Gulf of Fonseca); and later he discovered the Bay of Jiquilisco and the mouth of the Lempa River. He discovering the Salvadoran territory in this way.

Expedition of Pedro de Alvarado (June-July 1524)

In June 1524, Pedro de Alvarado left the town of Iximché in the current territory of Guatemala to begin the process of conquest of Cuscatlán. Under his command were some 250 Spanish soldiers and some 6,000 indigenous allies, mainly Tlaxcalans. After passing through the towns of Itzcuintepec, Atiepac, Tacuilula, Taxisco, Guazacapán, Chiquimulilla, Tzinacaután, Naucintlán and Paxco, he reached the western banks of the Paz River, and crossed it to enter the Nahuatl territories.

After a few leagues on the road, he arrived at a town of Mochizalco (now Nahuizalco), which Alvarado found deserted, because its inhabitants had abandoned it after finding out about the outrages he had carried out on the other side of the Paz River. He then continued to the town of Acatepec, which had also been abandoned by its inhabitants.

Alvarado continued south and reached the town of Acaxual (Acajutla); As he continued, he found himself half a league from the town with the Nahua army, engaging in a bloody battle. Alvarado himself was hit with an arrow in the femur, being seriously wounded.

After the battle, Alvarado withdrew to treat the wounded, remaining in Acaxual for about five days. Despite the seriousness of his wound, which forced him to remain in the rear, he marched against the town of Tacuzcalco (today Nahulingo), which was located to the south of the current city of Sonsonate; there an unequal battle began with enormous losses for the Nahua army. The Spanish rested for a couple of days and continued towards Miahuatán, which they found deserted.

Upon reaching the town of Atehuan (currently Atheists, La Libertad) he received messengers bringing a declaration of peace from the Lords of Cuscatlán; however Alvarado advanced towards the city of Cuscatlán and finding it deserted. It seems that in July 1524, Alvarado returned to Guatemala due to weather conditions.

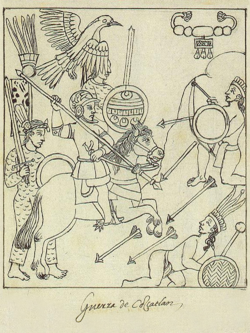

The story of the expedition led by Pedro de Alvarado to the territory of the Señorío de Cuzcatlán (described above) was narrated by Pedro de Alvarado himself in his Second Letter of Relationship sent to Hernán Cortés. In addition to this document, there are others such as: the Lienzo de Tlaxcala and the Very Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies. In the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, the Tlaxcalan indigenous people who accompanied the army of Pedro de Alvarado also narrate within the conquering campaign of the conqueror other battles that occurred within the current territory of El Salvador, which are: the battles of Cenzonapan (the same place where later Sonsonate would be founded), Tecpan Izalco, Yopicalco (Opico) and Xilopango (Ilopango). On the other hand, the Brief Relation of the Destruction of the Indies (written by Fray Bartolomé de las Casas) narrates a more conquering version by the Spanish than peaceful.

Foundation of San Salvador and the completion of the conquest (1525-1540)

At the end of 1524 or beginning of 1525 Pedrarias Dávila (conqueror of Panama and Nicaragua) sent Francisco Hernández de Córdoba to Honduras and he in turn sent Hernando de Soto to Olancho passing through Nequepio (name given by the indigenous Chorotegas knew the Señorío de Cuzcatlán), before this Pedro de Alvarado sent a group of men led by Gonzalo de Alvarado to found the town of San Salvador; The town of San Salvador was founded by Diego de Holguin and Gonzalo de Alvarado on April 1, 1525 in an unknown place. In 1526 an indigenous uprising broke out that forced them to abandon the town.

Between December 1527 and February 1528 Diego de Alvarado was sent to conquer the Señorío de Cuzcatlán, which he achieved, later the town of San Salvador was refounded by Diego de Alvarado in the place known as Ciudad Vieja, in the valley of Bermuda, 8 kilometers south of present-day Suchitoto. By 1528 it is estimated that approximately 90 towns were conquered and distributed among the Spanish. From 1529 to 1540 Luis de Moscoso, Diego de Rojas, Pedro de Portocarrero, among other captains of Pedro de Alvarado's army, continued and put an end to the conquest and pacification of El Salvador.

In 1530, an expedition led by Captain Luis de Moscoso finished the conquest of the eastern zone and founded the town of San Miguel de la Frontera. In 1530 Hernando de Chávez and Pedro Amalín (sent by Pedro de Alvarado) conquered the Payaquí Kingdom and defeated Copán Galel in Cítala, being arrested and finally executed in La Ermita. In 1537 Lémpira (leader of a Lenca resistance) was defeated in Honduras. In 1540 the area of El Salvador is pacified, leaving the current Salvadoran territory fully controlled by the Spanish.

The Spanish who conquered El Salvador

- Pedro de Alvarado (unfruitfully made the first attempt to conquer in 1524.)

- Gonzalo de Alvarado (Fundador de la Villa de San Salvador in 1525.)

- Diego de Alvarado (Foundó for the second time the village of San Salvador and in turn began the definitive conquest in 1528.)

- Diego de Rojas (Initiated the conquest of the lenca lordship in 1529 being then captured by Martín Estete and then released. In 1532, along with Pedro Portocarrero, pacified the Costa del Bálsamo.)

- Luis de Moscoso (brought Martin Estete and founded the village of San Miguel de la Frontera in early 1530)

- Hernando de Chávez y

- Pedro Amalín (They sold Copán Galel and conquered the Payaquí Kingdom in 1530.)

- Cristóbal de la Cueva (Founded for the second time the village of San Miguel in 1535 after being abandoned in 1534; the conquest of the lenca dominion ended.)

Colonial period (1540-1821)

The conquest of the territory meant the end of an era of indigenous population that had lasted several millennia. After thousands of years of isolation, the territory was forcibly incorporated into the Spanish Empire and became a colony. The Empire determined that the territory that El Salvador occupies today would form part of the General Captaincy of Guatemala, which depended administratively on the viceroy of New Spain. The surviving native population, decimated by the wars of conquest and by the new diseases coming from Europe, became "Indians" and his job would be to serve his conquerors.

Consolidation of Spanish rule (1540-1760)

In the years that followed the conquest, the Spanish introduced European animals and crops into the territory of El Salvador. There was a great effort to inculcate the culture and religion of the conquistadors to the indigenous people. Religious orders, especially the Franciscans and Dominicans, collaborated with the Spanish Empire in the evangelization process. The encomienda system was established to control the native population. This system was the reward that each conqueror received for his service to the Crown.

The encomienda consisted of assigning a specific number of adult indigenous people, who had to pay the encomendero a tribute in products or work. This system lent itself to many abuses against the aborigines. The slavery of the natives was expressly prohibited in 1542, by the New Laws. The Spanish Crown established the expiration of the encomiendas, generally after a period of two lives, (that is, after the death of the first generation of descendants of the encomendero), passing the natives to pay a direct tribute to the King. By the year 1550 there were a total of 168 towns (which had a total population of 17,500 people) distributed among the Spanish with the encomienda system.

Economy of the colony

As the Salvadoran territory lacked significant mineral wealth, agriculture became the basis of economic activities. Between 1550 and 1600, the two main activities were the cultivation of cocoa, carried out mainly in the Izalco region in the current department of Sonsonate; and the extraction of resin from the balsam tree in the coastal region. In the XVII century, the planting of cocoa declined, and it was replaced by the cultivation of jiquilite, the plant that serves as the base for the elaboration of the indigo dye.

Mixing and social stratification

During the colonial period, there was a process of miscegenation between indigenous people, blacks and Spaniards. By the time of Independence, mestizos made up the majority of the territory's population.

Salvadoran colonial society was highly segmented. On the one hand, there was a whole codification about the relations between ethnic groups. The concept existed that the position that a person occupied in the social scale, had to agree with a supposed mixture of bloods. The more Spanish blood, the better position, which is why the peninsular Spaniards occupied privileged positions, especially the highest positions in the colonial government.

Coexistence between the different ethnic groups was not entirely peaceful, proof of this is the rebellion of African slaves that occurred in the Mayor's Office of San Salvador between November and December 1624 when Pedro de Aguilar Lazo de la Alcalde was acting as mayor. Vega, the quelling of the rebellion was led by Captain Juan Ruiz de Villela, who successfully achieved his mission with an army made up of contingents of indigenous and ladino soldiers; the captured rebels would be executed in San Salvador in 1625.

Corsair Raids

During the colonial era, there were three incursions by corsairs into current Salvadoran territory: the first was Sir Francis Drake, who made two incursions into Salvadoran territory (first at the beginning of April 1579 in the Gulf of Fonseca and later in 1586 in the port of Acajutla), the second was the Englishman Thomas Cavendish who anchored in the Gulf of Fonseca in July 1587, finally the third incursion of corsairs into Salvadoran territory was that of a French team led by Eduardo Davis, Tomas Eatan and William Dampier who anchored in the Gulf of Fonseca in July 1684 and besieged the town of Santa María de Meanguera causing the depopulation of the Gulf.

Territorial organization in the first two centuries of the colony

New Spain (1535-1821) was the Spanish viceroyalty that stretched from the western United States to Costa Rica in Central America, with its capital in Mexico City. The General Captaincy of Guatemala (comprising the current territories of Guatemala, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua) depended on this viceroyalty.

From 1540 to 1580 the territory that in the future would be El Salvador, was divided as follows:

- Province of the Izalcos; it covered the current departments of Sonsonate and Ahuachapán; that region was taken away from the conquerors of San Salvador in 1529 and its populations given to neighbors of Santiago de Guatemala; at the beginning of the decade of the 1540s, the position of mayor mayor of the port of Acajutla, being the first Francisco de La Cueva; later its jurisdiction would be extended to the entire province of Alonso.

- Province of San Salvador; it covered the entire central area and the Department of Santa Ana, its origin dates back to the founding of the village of San Salvador in 1528, its rulers held the title of Senior Justice or Lieutenant Governor, the first Diego de Alvarado.

- San Miguel Province; it spread throughout the eastern area; its origin goes back to the founding of the village of San Miguel in 1530 being Luis de Moscoso his first Major Justice or Lieutenant Governor.

Since 1534 when Pedro de Alvarado left for Peru, the provinces of San Salvador and San Miguel (the latter would be uninhabited in 1534 because many of its inhabitants left on Pedro de Alvarado's trip to present-day Peru, later being refounded by Captain Cristóbal de la Cueva in 1535) would be governed by their ordinary mayors.

In 1560, King Philip II of Spain learned that there was a corregidor in Usulután who had extended his jurisdiction to the Province of San Miguel and that the mayors of Sonsonate had been added to the Province of San Salvador due to to the lack in both of major justice and lieutenant of governor; For this reason Felipe II ordered that both San Salvador and San Miguel continue to be governed by means of their ordinary mayors. Later, in 1575, a magistrate appeared in Tecoluca, this position and that of magistrate of Usulután did not have continuity.

In 1578 the rank of Mayor was given to the Province of San Salvador and Diego Galán was appointed interim Mayor, who held that position until 1580 when he handed it over to Juan Cisneros de Reynosa, who was his He once handed over command in 1581 to Alonso de Nava (who had been appointed Mayor by King Philip II). In the same year of 1580, the Province of San Miguel was incorporated into that of San Salvador, leaving the territory that would make up El Salvador divided only into the Mayor of Sonsonate (made up of the aforementioned territory) and the Mayor of San Salvador.

Events in the mayoralties of Sonsonate and San Salvador

Between 1556 and 1785, a total of 82 people held the position of mayor of Sonsonate; and from 1578 to 1786, 56 people served as mayors of San Salvador.

The first mayors of Sonsonate, as well as their Acajutla-based predecessors, were appointed by the Royal Audiencia of Guatemala, and held office for 1 to 2 years. In the year 1562 Francisco de Ovalle would be appointed, who would be the only one to be appointed with the title of corregidor.

Since 1563, the king would be in charge of naming the mayors of Sonsonate, and in the absence of the one designated by the monarch, the royal audience would be in charge of appointing an interim for the position. The first mayor of Sonsonate appointed by the king was Francisco de Magaña, who served from 1564 to 1568.

Magaña would be replaced by Pedro Xuárez de Toledo, also a royal appointment, who would be dismissed by the Holy Office of the Inquisition, arrested and taken to Mexico, but would manage to escape and take refuge in a convent where he would die. His case would be taken to the auto de fe of February 1574, where it would be declared that the charges for which he had been convicted were unjust. This was one of the three cases aired by the Holy Office that ended in an auto de fe, the other cases being that of the Irish Protestant sailor William Corniels (who lived as the surgeon barber Juan Martínez) and that of the Jewish-Portuguese merchant Marcos Antonio Rodríguez; the first would be tried and sentenced to death in 1575, and the second would be sentenced to life imprisonment but would be released by an edict of King Philip III in 1605.

In 1581, Alonso de Nava would be the first mayor of San Salvador appointed by the Spanish king; In 1585 he would be replaced by Captain Lucas Pinto, who would be the first whose jurisdiction would also cover the province of Choluteca (present-day Honduran departments of Valle and Choluteca), said province would remain in the territory of that mayor's office until the beginning of the century XVII. Likewise, in that decade Juan de Mestanza y Ribera, who was a friend of the writer Miguel de Cervantes Savaeedra, who mentions him in some of his writings, would hold the position of mayor of Sonsonate.

During the XVI century the Sonsonateca mayor's office experienced an economic boom due to the cultivation and trade of cocoa; but in the XVII century due to the decline of the cacao plantations, the reduction of indigenous labor (due to diseases), and the restrictions on trading certain products from other Spanish territories (such as wine from Peru), the number of ships arriving at the port of Acajutla would be reduced, which would cause a strong economic reduction that would cause the emigration of several inhabitants to other territories and that the smuggling of these prohibited products would increase. While the mayor's office of San Salvador would become one of the main economic engines of the General Captaincy of Guatemala, thanks to the cultivation and trade of indigo, and to a lesser extent for the balm.

In the year 1611, the president, governor and captain general of Guatemala Antonio Peraza Ayala de Castilla y Rojas, count of La Gomera, began to govern; who would be the first ruler of the Guatemalan kingdom of noble origin and who was given the power to confer military titles on the rulers of the provinces. Therefore, from then on the mayors would also receive the title of lieutenant captain general, the first being Pedro de Paz y Quiñones in Sonsonate, and Pedro de Aguilar Lazo de la Vega in San Salvador.

In 1636, during the mandate in San Salvador of Juan Sarmiento de Valderrama, the town of San Vicente would be founded, which would later also be the headquarters of its own province (always within the mayor's office) that would cover the current paracentral zone.

Between the 16th and 17th centuries, several major mayors would stand out mainly for the fight against piracy, either in their territory or in providing help to other provinces that had this problem. Due to this problem, the mayors of those centuries would come from the Spanish army or navy.

Some mayors would be dismissed due to accusations of mismanagement by the administration or due to problems with the royal treasury. That would be the case in San Salvador of: Pedro Farfán de los Godos, in 1619; Juan de Miranda, in 1680; Francisco Chacón Medina y Salazar, in 1708; and Bernabé de la Torre Trasierra, in 1759.

In the year 1698 (and until his death the following year), Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán would hold the position of mayor of Sonsonate; who would write a work on the history and situation of Guatemala at that time, which is commonly called Florida Remembrance. Likewise, in 1699 Bartolomé Gálvez Corral came to power in San Salvador, who would retire from office for health reasons in 1703, and who would be the father of the also mayors of that jurisdiction: Cristóbal (from 1734 to 1737, and from 1765 to 1766) and Manuel (from 1737 to 1740), being the last author of a work on the situation in which he was that territory at the time.

In 1722, Francisco Antonio Carrandi y Menán would begin to govern in Sonsonate, who would be in charge of caring for the populations affected by the eruption of the Santa Ana volcano that year, repairing the bridge over the Rio Grande, fixing various parishes, build the first aqueduct and public fountains in Ahuachapán, repair the hospital of the order of San Juan de Dios, improve agriculture in that territory, among other things. He would remain in that position until 1733, when he was removed by royal writ.

Between 1757 and 1764 Bernardo de Veira ruled in Sonsonate, who stood out among other things for the opulent celebration he held due to the rise of King Carlos III; Said celebration would begin on January 26, 1761 and would last for 16 days, being the first occasion that the consumption of coffee, drink and cultivation is mentioned, which will be very important in the future of the history of El Salvador.

After the dismissal in San Salvador of Bernabé de la Torre Trasierra, and while his trial continued, several interim mayors succeeded one another, the last of them being Manuel Fradique y Goyena, who was appointed in 1766 to succeed and complete the term for which his father-in-law Cristóbal de Gálvez Corral had been appointed. In 1771 Bernabé de la Torre would be restored, but he would die 2 years later. In 1777 he would be named Manuel Fadrique again, during this new period he would be in charge of promoting the cultivation of corn, cleaning the city of thieves, paving the streets and fixing the streets of the capital, Santa Ana, Zacatecoluca, San Miguel and San Vicente, among others. other things. Goyena would remain in office until 1786, being the last mayor of San Salvador. During that time, Manuel García de Villalpando (from 1777 to 1785) and Antonio López Peñalver y Acalá (from 1785 to 1794) served in Sonsonate.

Bourbon reforms (1760-1808)

In the year 1700, with the accession to the Spanish throne of Felipe V, the Bourbon dynasty was inaugurated. The kings belonging to this new royal family, including Felipe V, implemented during the XVII century a series of economic and administrative reforms in the colonies. These reforms gained greater force in 1759 with the coronation of Carlos III and began to be implemented throughout the Captaincy General of Guatemala from 1765 with the arrival in Guatemala of Captain General Pedro de Salazar Herrera.

Economic reforms

With the implementation of the Bourbon reforms in the Salvadoran territory, the alcabala taxes were reduced, the tax collection system was improved and monopolies or tobacconists were established; This was intended to prevent merchants from evading taxes, which had some success, but merchants devised new ways to evade taxes for which the colonial authorities should always be vigilant.

The Spanish government with the new reforms reduced ecclesiastical power through attacks on church property and privileges. And they partially supported the producers of the Salvadoran territory.

Administrative reforms and reorganization of the territory

In 1785, as part of the reforms carried out by the Bourbon dynasty, the Municipality of San Salvador was created (which included the territory of the Mayor of San Salvador), the mayors were selected based on their merits and his fidelity to the king; and they had to exercise more direct and effective control than the mayors. Being selected as the first mayor of San Salvador José Ortiz de la Peña, who held that position until 1789 when he was replaced by Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet.

The Intendancy of San Salvador together with the Mayor of Sonsonate (whose rulers, from the Bourbon reforms would also receive the title of sub-delegate of the Royal Treasury) comprised the current territory of El Salvador. This Alcaldía Mayor would continue its existence until shortly after independence when it would join San Salvador. Both administrative divisions of the Spanish Empire depended on the Captaincy General of Guatemala and this, in turn, depended on the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

Mayors of San Salvador and Mayors of Sonsonate

As mentioned, the first mayor of San Salvador was José Ortiz de la Peña who was in charge of organizing the territory and who in 1786 appointed the royal surveyor Francisco José Vallejo to found a new town that would be San José Guayabal. In 1789 Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet would arrive as mayor, who would be in charge of giving stability to the territory, pursuing smuggling on the coasts, fighting piracy (arming the ports and strategic places), trying to reorganize the militias, freeing agriculture from legal obstacles, introduce the silkworm, request that the tobacconist's shop be lifted, and reorganize the indigo growers' Board in the form of a mortgage bank, establish the vaccine board, establish population principles, protect consumers, regulate the weights and measures used by the sellers, try to regulate the sale of royal lands, establish primary and craft schools, and also that he would found the town of Dulce Nombre de María.

Both de la Peña and Carondelet were mayor governors, but starting with José Antonio María de Aguilar (who would govern on an interim basis, being the legal adviser, after Carondelet was appointed governor of Louisiana in 1791) the title would be of superintendent. In 1793 Ignacio Santiago Ulloa would take office, who would rule until his death on January 1, 1798; after which, and until 1804, several interim governments succeeded each other (including some mayors of San Salvador), among which were: Bernardo José de Arce (father of the independentista Manuel José Arce, and one of the participants of the independence movement of 1811), José Rosi (who would be commander of the militias of San Salvador from 1806 to 1821) and Buenaventura de Viteri (father of the first bishop of San Salvador Jorge Viteri y Ungo).

In the mayor's office of Sonsonate, Antonio López Peñalver y Alcalá would serve as mayor, from 1784 to 1794; who would try to promote mining, would renew all the local judges, would make new strict measures to thus cultivate new lands and reduce unemployment, would found new indigenous schools, would order the roads to be repaired, would start water distribution works in Ahuachapán, would clean up and develop the abandoned cacao crops, ensuring that the indigenous people could also take care of their own crops, introduce indigo and cotton without neglecting wheat, build new warehouses in the port of Acajutla and a fresh water supply system.

After Peñalver, and after Agustín Gutiérrez y Lizaurzábal had been interim, Manuel Cotón would arrive as mayor of Sonsonate in 1795; who on July 30 of that year would issue an edict in which he would prohibit mulattoes, Afro-descendants or mestizos from buying and reselling corn, chickens, fresh fish, rabbit, fruit, vegetables, etc. within the Sonsonateca town and five leagues around. In 1802, Cotón would be dismissed by the President-Governor and Captain General of Guatemala Antonio González Saravia for having confiscated the 10,000 pesos of flour that the merchant José de Irisarri was going to embark on the North American frigate "Diana"; between that year and 1810 there would be several interim mayors.

In 1804 Antonio Gutiérrez y Ulloa would arrive as mayor of San Salvador, who would write the book General State of the Province of San Salvador, where he narrates the situation of the populations that were part of the mayor's office; and that he would be removed by the first independence movement of 1811, being replaced by José Mariano Batres y Asturias, who would serve until December 3 of that year, being replaced by José Alejandro de Aycinena (sent from the Guatemala City Council). Aycinena would be elected State Councilor and would leave for Spain in 1812; leaving José María Peinado in his place, who would face the second independence movement of 1814, shortly after he would be dismissed, he would be reinstated in 1818, and he would die in office in 1819, being replaced by Pedro Barriere.

In 1810 Mariano Bujons arrived as mayor of Sonsonate, who sided with the Guatemalan government during the first independence movement of 1811, being willing to send troops to that area, but this was not necessary in the end. Bujons would occupy that position until 1818, being replaced by José Manuel Nájera y Batres.

Independence Process (1808-1821)

Since the last decades of the XVIII century, in various regions of Latin America, there have been several rebellions against the dominance Spanish, some more successful than others. In Central America, the feeling of independence began to grow among the Creoles, who, influenced by the liberal ideas of the Enlightenment, saw in the process of independence from the United States and in the French Revolution an example to follow. It is known that leaders of the Central American independence movement such as José Matías Delgado, José Simeón Cañas and José Cecilio del Valle, were aware of the ideas of individual freedom and equality before the law advocated by the Enlightenment.

In the first decade of the 19th century, the Spanish colonial authorities carried out a series of unpopular fiscal and economic measures, such as the increase in taxes and the consolidation of state debts, to finance the European wars of the Spanish Crown. These measures increased the feeling of independence among the Creoles.

Historians consider that the phenomenon that triggered the process of independence in Central America was the Napoleonic invasion of Spain in 1808, which meant the temporary collapse of royal authority.

In the period from 1808 to 1814, several important uprisings took place in the territory of the Municipality of San Salvador:

- The Uprising of November 5, 1811. He was defeated in December 1811. Known as the First Grade of Independence, was headed by José Matías Delgado, Manuel José Arce and the Aguilar brothers in San Salvador. It spread in the following days of November to the cities of Santiago Nonualco, Usulután, Chalatenango, Santa Ana, Tejutla and Cojutepeque. There were 2 related uprisings, which acquired relevance, that of December 20, 1811, which occurred in Sensuntepeque, and that of November 24, 1811, which occurred in the city of Metapán.

- El Alzamiento de 24 de enero de 1814, ocurrido en San Salvador, no tuvo éxito y la mayoría de los líderes independienteistas fueron detenidos; siendo uno de ellos, Santiago José Celís, asesinado. In this movement there was wide popular participation.

At the same time, the Central Supreme Board (which took power in Spain as a reaction to the French occupation) in 1809 ordered a lottery to designate a representative to the board for each royal audience, each city council of Spaniards (which in the case of the current Salvadoran territory were: Sonsonate, San Salvador, San Vicente, San Miguel and Santa Ana; the latter since 1806) would choose a person who would participate in that raffle. The Sonsonate city council would first elect Alejandro Ramírez and then Dean Isidro Sicilla; the one from Santa Ana to Domingo Figueroa; that of San Vicente firstly to José Cecilio del Valle and then to the vicar Manuel Antonio de Molina; and that of San Miguel to the vicar Miguel de Barroeta. Although the final winner of the draw was Barroeta, he could not be part of the Supreme Board because he was replaced by the Regency Council.

On February 14, 1810, the Council of Regency would order the town halls, which were party heads (which in the Captaincy General of Guatemala was interpreted as the headquarters of the governorship or intendancy), to choose a deputy by lottery for the general cuts; being elected in San Salvador the presbyter José Ignacio Ávila, who would participate in said courts that issued the Spanish constitution of 1812. With this constitution, the intendancy of San Salvador and the mayor's office of Sonsonate became part of the province of Guatemala; its leaders also received the title of political chief; Town halls were installed in towns with more than 1,000 inhabitants, with the members of the town halls elected by the citizens; and elections would be held for the formation of the provincial council of Guatemala, which would boost the economy and progress of that province, and that the priest José Simeón Cañas would be representing Sonsonate and José Matías Delgado for San Salvador.

In May 1814, Ferdinand VII returned to Spain as king, and immediately reestablished absolutism, repealing the Constitution of Cádiz. The effects of the royal measures were felt in Central America, where the Captain General of Guatemala, José de Bustamante y Guerra, unleashed a persecution against the independentistas and the defenders of liberal ideas, which would last until the removal of Bustamante in 1817.

In 1820, the Irrigation Revolution in Spain restored the validity of the Constitution of Cádiz. The Captain General of Guatemala, Carlos Urrutia, swore the Constitution in July of that year and shortly after elections were called to elect city councils and provincial councils (the latter being the representative for San Salvador, the priest José Matías Delgado, and for San Miguel the priest Manuel Antonio de Molina), in addition to allowing freedom of the press in the territory of the Kingdom of Guatemala. Taking advantage of the atmosphere of freedom, two new newspapers began to be published in Guatemala: El Editor Constitucional under the direction of the Guatemalan Pedro Molina, who defended very liberal positions, and El Amigo de la Patria led by the Honduran José Cecilio del Valle, who defended more conservative positions. On May 8, 1821, the Spanish courts decreed that all the Intendencies be elevated to the rank of province (that is, that their leaders also have the title of superior political chief, and that they can establish their own provincial deputation), for which reason the intendancy of San Salvador becomes the Province of San Salvador; while the mayor's office of Sonsonate is part of the Province of Guatemala. In June 1821, Captain General Urrutia was replaced by Gabino Gaínza. In August the news of the Independence of Mexico reached Central America, under the terms established in the Iguala Plan of Agustín de Iturbide. Faced with this new reality, Gaínza convened the meeting of notables on September 15.

Central American Independence and Federation (1821-1841)

Independence and subsequent events

On September 15, 1821, at a meeting in Guatemala City, the representatives of the Central American provinces declared their independence from Spain; establishing the provincial council of Guatemala as a provisional advisory Board, chaired by the former Spanish Captain General (Gabino Gaínza), and in which the priests José Matías Delgado and Manuel Antonio de Molina (who previously were in the provincial council), and from the mayor's office of Sonsonate the presbyter Ángel María Candina. The news of independence reached San Salvador on September 21. (1) (2)

When Central American independence came to fruition, only three options remained for the nascent union of provinces: first, to preserve the unity of the provinces; second, to become independent in well-defined nations; or third, to annex to the Mexican Empire of Agustín de Iturbide.

On October 4, 1821, it was up to the province of San Salvador to elect the members of its provincial council, which would help the superior political chief of the province (at that time Pedro Barriere) in the administration and progress of the territory. But Barriere, who was in favor of annexation to Mexico, would have those on the opposite side arrested; by which the provisional consultative Board of Guatemala would name one of its members, the priest José Matías Delgado, as the new mayor-political chief on October 9, who would carry out the elections for provincial deputation, being elected: Manuel José Arce, Antonio José Cañas, Juan Manuel Rodríguez, Sixto Pineda, Juan Fornos, and Basilio Zeceña.

In the mayor's office of Sonsonate, the mayor José Manuel Nájera y Bátres would refuse to accept independence, so in October of that year the provisional advisory board would appoint José Fernández Padilla as his successor, who would accept independence on October 7. But, in November of that year, the Sonsonateco council would decree the annexation to Mexico, for which troops from Guatemala and the town of Santa Ana would be sent to pacify the territory, which would be achieved and Padilla would be dismissed and replaced in December of that year. year by Juan Fermín Aycinena.

Annexation and war against the Mexican Empire

The news of independence baffled most of the conservative groups in the different provinces and municipalities of American Center. The concern of the conservative sectors was calmed when the Guatemalan authorities received a letter from Iturbide, who had proclaimed himself Emperor of Mexico, inviting Central America to join the empire.

The Board decided to consult the municipalities and two-thirds of them responded, of which 168 approved the annexation, and two, San Salvador and San Vicente, refused to join Mexico. The Junta de Guatemala declared the annexation to Mexico on January 5, 1822. Iturbide sent Mexican troops under the command of General Vicente Filísola to ensure said annexation.

On January 11, 1822, the presbítero Delgado and the provincial council of San Salvador decided to declare the separation of the province from the former captaincy general of Guatemala, to establish itself as a governing junta, and to prepare for war against Guatemala and Mexico.

Gaínza would first command Nicolás de Abos y Padilla, and then Manuel Arzú, but both would be defeated. On June 22, Vicente Filísola would be named political chief and captain general of Guatemala, and would be in charge of subduing the rebel municipalities of San Salvador and San Vicente.

In Sonsonate, on February 24, 1822, due to Aycinena's poor health, Colonel Lorenzo Romaña would be appointed as mayor, who would form a contingent of troops to first join Arzú and then Filísola to defeat the province of San Salvador.

The governing body of the province would designate the presbyter Delgado as bishop of San Salvador and would send Juan de Dios Mayorga as deputy to the congress of the Mexican empire; and after it was dissolved, it would convene a congress (which was installed on November 10 of that year), which would decide the annexation of the province to the United States (which in the end would not occur due to the fall of the Mexican Empire)..

General Filísola entered San Salvador with his troops on February 9, 1823, after several months of resistance. While the troops of the province would remain on the fighting foot, mobilizing in the towns of the paracentral zone, until they surrendered in Gualcince (Honduras) on February 21 of that year.

When Filísola returned to Guatemala, leaving General Felipe Codallos in command of the province, he received the news that Iturbide had been overthrown and that Mexico had become a republic. Filísola being faithful to his emperor and not to Mexico, he asked the Junta of Guatemala to convene the Central American deputies to make a decision.

On May 25, a mutiny would force General Codallos and his troop of 500 Guatemalan and Mexican soldiers to leave the province. He being replaced in command of the province, by the advisory board (consisting of Mariano Prado, Colonel José Justo Milla and Colonel José de Rivas); that he held office until June 17, when he handed over control to its president, Mariano Prado, while in Sonsonate, instead of Romaña, Miguel de Mendoza would be mayor mayor.

After the departure of the Mexican and Guatemalan troops, a new provincial council was elected, which would be chaired by the political chief Mariano Prado, and which would be made up of Manuel José Durán, José de Rivas, Juan Fornos, Pedro Mártir Acosta, José Inocente Escolán, Mariano Zúñiga, Casimiro Antonio Morales, and Manuel Trinidad Estupinian.

Absolute independence and United Provinces of Central America

The Central American assembly, whose president was the priest José Matías Delgado, proclaimed independence from Spain, Mexico or any other nation on July 1, 1823, and the United Provinces of Central America were established (3).

On September 27, the deputation, due to the rebellion of Rafael Ariza, would establish itself as a government junta, raise a force of 2,000 men, and send a contingent of 750 soldiers to Guatemala commanded by Colonel José de Rivas; in turn designating Captain Pedro José Arce to notify the Guatemalan authorities of the advance of the troops. This contingent, after fulfilling its purpose, would return to the province via Sonsonate, forcing that mayor's office to join the province and Pedro José Arce becoming the last mayor of that jurisdiction.

On September 30, the board would return to the status of deputation; but on October 27, due to the members of the deputation considering that the conservatives had a significant share of power in the government of the united provinces, it would re-establish itself as a government junta.

On December 22, 1823, the Mayor of Sonsonate and the Province of San Salvador agreed to unite, Ahuachapán refused until February 7, 1824. On the other hand, on February 2, 1824, the governing body of the province having only the bases of the federal constitution, would call elections for the state constituent congress.

On March 5, the constituent congress would be installed in San Salvador, in the building of the convent of San Francisco (where today is the ex-barracks or handicrafts market); which would be made up of 3 deputies from the mayor's office (2 from Sonsonate and 1 from Ahuachapán) and 15 from the province of San Salvador; and whose first president would be José Mariano Calderón. Said congress, on April 21, would designate Juan Manuel Rodríguez as political head of state; on May 7, he would decree the creation of the armed forces (with the name of the legion of freedom), whose bill had been prepared by Manuel José Arce; and on May 18, he would appoint Joaquín Durán y Aguilar as the first president of the Supreme Court of Justice.

On June 12, congress would issue the Constitution of the state with which the mayor's office of Sonsonate and the province of San Salvador are fully united and form the State of El Salvador, belonging to the United Provinces of Central America. On October 1, Rodríguez would be replaced by the elected deputy head of state Mariano Prado, who would serve until December 12 when Juan Vicente Villacorta Díaz came to power, the first supreme head of state elected by vote of the population.

Federal Republic of Central America

The Central American Constituent Assembly, chaired by the Salvadoran hero José Matías Delgado, promulgated the first federal Constitution on November 22, 1824.

In 1825, the Salvadoran Manuel José Arce was elected as the first president of the Federal Republic, supported by the liberals, but in order to govern he sought the support of the conservatives who were the majority in the Federal Congress. In 1826 the government of Arce clashed with the liberal government of the State of Guatemala, breaking out the civil war in all of Central America with the exception of Costa Rica. The civil war lasted until 1829. The liberals united around the Honduran Francisco Morazán, who managed to defeat the federal troops militarily and expelled Arce from Central America in 1829; him being elected as President of the Federation in 1830.

The State of El Salvador gave itself its own Constitution on June 12, 1824, being head of State, the independentista Juan Manuel Rodríguez. Since colonial times there was great suspicion between the elites of San Salvador and Guatemala and after independence, there was an open confrontation. While the government of the Federal Republic resided in Guatemala, there were numerous confrontations between it and the state government of El Salvador. In 1827 war broke out between the government of the State of El Salvador and the federal government of Arce. In 1830 the Salvadorans elect José María Cornejo, a conservative, as Head of State, who opposes the new federal president Morazán and goes so far as to declare the separation of the Salvadoran State from the Federation. Morazán with his federal troops entered San Salvador, dismissing Cornejo and leaving Mariano Prado in power, who shortly after is replaced by Joaquín de San Martín, who once again announces the separation of the Federation. Morazán then invaded El Salvador and transferred the federal capital to San Salvador, in 1834. After the transfer of the federal government to San Salvador and until 1840, Morazán imposed a strong control over the government of the State of El Salvador. In 1837 Rafael Carrera, supported by the clergy and the conservatives of Guatemala, rose up in arms from Quetzaltenango against the Federation. Carrera defeated Morazán, who left San Salvador in 1840, heading for Costa Rica. After Morazán's exile, a new conservative government was installed in El Salvador, headed by Juan Lindo.

One of the causes of the defeat of the liberals and the dissolution of the Central American Federation was their anti-clericalism, the strong provincial sentiment of each region, and also the approval of a series of laws that provoked negative reactions among the indigenous population. The Courts of Cádiz had abolished in 1812 the tributes of the Indian towns. Every time they wanted to establish themselves again, negative reactions arose in the indigenous communities. When Mariano Prado as Head of State of El Salvador introduced the system of juries and a new tax that all citizens had to pay, there were uprisings in Izalco and San Miguel, producing in 1833 the uprising of the Nonualco indigenous people, led by Anastasio Aquino, in the town of Santiago Nonualco in the current department of La Paz.

Fights between liberals and conservatives (1841-1876)

On February 2, 1841, a Constituent Assembly proclaimed the separation of El Salvador from the Central American Federation; and on the 16th and 18th of the same month and year, respectively, approved the Legislative Decree of the Foundation of the University of El Salvador and issued the first Constitution of El Salvador as a sovereign and independent State of the Federal Republic, which contemplated the possibility of carrying out the reorganization of the missing Central American Federation. However, in view of the insurmountable difficulty of achieving this objective, the Salvadoran parliament, acting in accordance with the provisions of Article 95 of the Constitution of 1841, issued the Legislative Decree of January 25, 1859, published in the Gaceta del (Sic) Salvador n.º 88, Volume no.

During the three decades following the disintegration of the Federal Republic, El Salvador experienced a period of great political instability, due to the rivalry between liberals and conservatives, conflicts with neighboring states, and the lack of consolidation of the National identity. The struggle for the government between the two factions reached the extreme that, while one of the two groups was in power, the other party did not hesitate to ask the neighboring countries for help to overthrow the opposing government, which is why in this period there were frequent insurrections and revolts, maintaining a constant climate of civil war.

In Central America, the liberals supported the legal recognition of individual liberties, the liberalization of trade, the separation between Church and State, in addition to defending Central American unionism; while, the conservatives, on the contrary, supported maintaining many of the colonial institutions, the collaboration between civil and ecclesiastical authorities, and preferred the independence of each country from the old Central American Federation.

Caudillismo

It must be considered that both the liberal faction and the conservative faction were organized around personalist leaderships (caudillos). This phenomenon meant that there were no institutional armies and each caudillo recruited his own militia. In Central America, the top liberal caudillo was the Honduran Francisco Morazán and the main conservative caudillo was the Guatemalan Rafael Carrera y Turcios; both had followers in El Salvador. Salvadoran caudillos such as Gerardo Barrios (liberal) and Francisco Malespín and Francisco Dueñas (conservatives) represented these antagonistic positions.

The first of the local caudillos of El Salvador was Francisco Malespín who ruled from 1840 to 1845. First indirectly, through presidents Norberto Ramírez, Juan Lindo and Juan José Guzmán, and from 1844 directly as president. A few days after assuming power, Malespín decided to invade Nicaragua and left General Joaquín Eufrasio Guzmán in command.