Salvador Salazar Arrue

Luis Salvador Efraín Salazar Arrué, better known by his pseudonym Salarrué (Sonzacate, October 22, 1899 - Los Planes de Renderos, November 27, 1975) was a Salvadoran artist. He worked in the field of literature and the plastic arts, but his narrative work has been the best known of his creations, among which Cuentos de barro and Cuentos de dicks.

His artistic gifts were revealed from a very young age. He studied painting in the United States, where he met the costumbrista book & # 34; The book of the tropics & # 34; Arturo Ambrogi, who encouraged him to return to his country to dedicate himself entirely to art. Starting in the 1930s, and although he preferred to stay away from politics, he worked closely with the military regimes in turn to promote the cultural policies of the time. Since 1946 he served as El Salvador's cultural attaché in the United States.

He returned to El Salvador in 1958, and soon after finished his literary production, although the books published in previous years continued to be reprinted. In his later years he won recognition for his work, despite the fact that he subsisted modestly in his house located in Los Planes de Renderos. He died of cancer, mired in poverty.

Salarrué was a believer in Theosophy, a doctrine that influenced his artistic production. He has been considered one of the precursors of the new Latin American narrative, and the most important narrator in the history of El Salvador.

Biography

Childhood and youth of Salarrué

In the 19th century, the pedagogue of Basque origin, Alejandro de Arrué y Jiménez, who had worked in various countries Hispanic Americans, he married Miss Lucía Gómez, a native of Sensuntepeque, El Salvador, in Guatemala. The Arrué Gómez couple had several children, including Luz and María Teresa. Both had a literary vocation; but it was Luz, after Miranda (already when the family lived in El Salvador) who managed to get the journalist Román Mayorga Rivas to include her in the poetry anthology Salvadoran Garland .

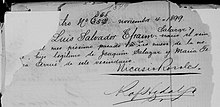

For her part, María Teresa married Joaquín Salazar Angulo, an incipient musician from an honorable family. However, the relationship did not prosper due to various circumstances, so the young mother had to support her children Joaquín and Luis Salvador Efraín alone, who was born on a family farm located in the El Mojón canton that would become part of the urban area. from the municipality of Sonzacate, in Sonsonate. In the following years, the Salazar Arrué lived with financial difficulties, although they received the support of close relatives, since their respectable ancestry favored them.

Luis Salvador's childhood was spent in the splendor of the tropical nature of Sonsonate. Although shy and far from horseplay, he was distinguished by his ability to invent stories. When he was eight years old, money problems forced his mother to move, so the youngster alternated his residence between San Salvador and Santa Tecla where He lived in the residence of his Núñez Arrué cousins, among whom was Toño Salazar, a future renowned cartoonist. For his part, his mother worked as a seamstress and came to have a dressmaking academy. Toño left a description of his cousin in those years:

"Ephraim was long, tall, with an undulating hair orange and honey... Salazar Arrué looked at him some archangel, a rare aura put him in solitude...He had some of the air of Sonsonate's palm and some childhood retained."

Luis Salvador attended primary school at the ancestral institution Liceo Salvadoreño. He completed secondary school at the National Institute for Men and later at the Academy of Commerce, where he did not finish his studies, but he achieved good grades.

His artistic vocation already manifested itself at the age of eleven when one of his compositions was published in the Diario del Salvador by Román Mayorga Rivas. The achievement was not fortuitous, since in the Núñez Arrué house he had to interact with characters from the local intelligentsia who visited the house.

First steps as an artist

Luis Salvador became interested in painting, and together with his cousin Toño he enrolled in the Spiro Rossolimo school in San Salvador. Despite the fact that he could not continue paying for his studies, thanks Due to the political influence of his relative, César Virgilio Miranda, he obtained a scholarship from President Carlos Meléndez to study in the United States, where he left in 1916.

In that country he studied at the Jesuit Rock Hill College, near Baltimore, but the religious environment of the study center was not to his liking. Later, and with the help of the Salvadoran ambassador in Washington, D.C., he entered a school in Danville, Virginia, where he improved his learning of the English language. In 1917 she enrolled in the Corcoran School of Arts in the US capital, where she received a formal education, but far from the trends of modern art. At that time, his work was influenced by Ignacio Zuloaga and he managed to exhibit his paintings in the gallery of a Japanese businessman named Hisada.

However, it was in New York where a transcendental event happened in his artistic life, since he had an "encounter" with his country's literature at the Brentano bookstore. In that place he learned about the costumbrista work El libro del trópico by Arturo Ambrogi, which filled him with nostalgia for his land.Years later, he would affirm that he came to memorize the index of the book as if it were a poem

Therefore, he decided to return to El Salvador in 1919. There the young man proposed to make a living from painting, but he had to face the reality of the non-existent art market and some of his paintings ended up giving them away. Despite everything, the country was experiencing the journalism boom of the 1920s, so he dedicated himself to collaborating with illustrations and articles in various newspapers to earn a living. He signed his articles with the pseudonym "Salarrué".

In 1923, he married Zélie Lardé, also a painter. The couple had three daughters: Olga Teresa, María Teresa and Aída Estela. In those years Salvador worked as an officer of the Red Cross in San Marcos, department of San Salvador, a town that had been affected by floods in 1922. There he decided to set up his painting studio, and lived in a gallery lent by that same organization. He also began to surround himself with artists and intellectuals of the time, such as Serafín Quiteño, Claudia Lars and Alberto Guerra Trigueros, who would become his best friend.

In the midst of economic hardship, but recognized within the Salvadoran cultural environment, he published his first book in 1926: El Cristo negro, which received good reviews. He also had a pictorial exhibition at the Society of Commerce Employees of San Salvador. The following year he received the regional prize for narrative from the newspaper El Salvadoreño with the work El señor de la bubbula , celebrated by several intellectuals, among them the Guatemalan Rafael Arévalo Martínez.

His artistic activity also included theater, when on October 5, 1928 he played a role in the play Quo Vadis? with the character of Petronio, and also premiered the drama La chain. Days later, the newspaper Patria showed this criticism of the artist: «Salarrué is for us the most outstanding head and the most complete personality of the young generation, whenever matters of arts or letters we have to refer to". It should be added that since 1929 he worked as a professor of indigenous mythology and decorative art at the National School of Fine Arts. Cementing his prestige as a writer, he continued writing in national and Central American newspapers, such as: For everyone, The friend of the people, The Salvadoran, Queremos, and especially Homeland i>, directed by Alberto Masferrer.

Around thirty years of age, Salarrué began to feel the extracorporeal splitting. The search for a satisfactory explanation for this experience led him to study Theosophy, through his friend Guerra Trigueros. In this context, in 1929 the publishing house of Patria began to publish the fantastic stories of O-Yarkandal, and in 1932 Remontando el Uluán with similar characteristics was printed.

The 1930s and the “martinato”

In the context of the global economic depression, the decade of the 1930s was one of social unrest in El Salvador. In 1931, the presidential elections were held, in which Masferrer and Guerra Trigueros supported the engineer Arturo Araujo of the Labor Party, which had postulates of the vitalist doctrine of Masferrer himself. Salarrué received an invitation to join the movement, but he preferred to stay away from politics, and in a letter he explained his reasons:

"I am an anti-green man, my nature as an artist makes me depart from everything that is group, caste, sect, party, conciudadanía and ismos in general.I want to go freely, without party commitments, reserving the right to be outside of everything that is regulation, canon or condition; my quality of artist gives me such a right."

The elections were won by Araujo, but he ended up being overthrown by a coup in which General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez participated, also a Theosophist like Salarrué and who was also the protagonist of the harsh repression of the insurgents of the peasant uprising of 1932. This infamous episode of Salvadoran history would form part of some of the writer's works, either explicitly or implicitly. However, Salarrué would continue to avoid the political frenzy of the country, since he clung to a "primordial" concept to understand the world, as evidenced in a writing called My response to the patriots , probably influenced by the book Las fuerzas morales by José Ingenieros, and which was published in the weekly American Repertoire by Joaquín García Monge:

"I don't have a homeland, I don't know what a homeland is. What do you call homeland the men understood by practical? I know you understand for your homeland a set of laws, a machinery of administration, a patch on a map of shriek colors...I have no homeland but I have a homeland...I don't have El Salvador...I have Cuscatlán, a region of the world and not a nation."

It should be added that in said statement Salarrué expressed his disagreement with the objectives of the Salvadoran Communist Party, involved in the peasant movement; but he would keep good memories of its leader Agustín Farabundo Martí, whom he declared a friend of in an article published in Patria , in which he also called him an "ideal man" who deserved admiration for " integrity" of him.

On the other hand, and in terms of his literary work, one of Salarrué's best-known works began to spread abroad. It happened that in 1931 the Chilean Gabriela Mistral had made a brief visit to El Salvador, and after learning about Salarrué's work she gave García Monge part of the Cuentos de barro that would be published in the Repertorio Americano. These stories had begun to be published since 1928 in the Excélsior Magazine, and also in Patria along with others called Cuentos de cipotes , which in turn had as background a section called News for children. In 1934 the work Cuentos de barro would appear as a definitive edition with illustrations by José Mejía vines.

On September 4, 1932, the director of Patria, Alberto Masferrer, died. Guerra Trigueros assumed the direction of the newspaper and Salarrué served as editor-in-chief. He himself was in charge of directing the newspaper when Guerra Trigueros was persecuted by the regime and also came into conflict with Arturo Ambrogi, the same author who had dazzled him with El libro de trópico, but who held the position of Press Censor in the regime of Hernández Martínez who had assumed the presidency of the country since 1931.

Precisely, the administration of General Hernández Martínez was characterized by the censorship of the radio media, the written press and public entertainment. It was the State itself that was in charge of cultural policies, through a presidential project that fostered appreciation of the nation, the charm of the terroir, and the promotion of indigenismo. Salarrué, according to Álvaro Rivera Larios, also nourished by "aesthetic ideas and some formal models with which other artists in Latin America had already worked", which had as their theme the popular language, the peasant and the native landscape, he developed his artistic work in that environment as did other intellectuals in the country.

In the following years, Salarrué would work closely with the military regimes. It is said that in 1935, along with other Theosophist communicators related to Hernández Martínez, he tried to organize the arrival of Jiddu Krishnamurti to the country; part of the government the designation as official representative in the first Central American Exhibition of Plastic Arts that took place in Costa Rica. In 1937 he was part of the Commission for Intellectual Cooperation of El Salvador, attached to the League of Nations, and thanks to these positions he was able to show his paintings in various international exhibitions such as Guatemala, the United States and Canada.

In 1938, he worked on a commission that would be in charge of selecting books that would be published with state funds, and two years later he held the position of director of the Amatl magazine of the Ministry of Public Instruction. However, according to the historian Carlos Cañas Dinarte, the spirit to participate in these government programs began to wane when he was part of the Friends of Art group, which between 1935 and 1940 had organized exhibitions in the country, but which were interrupted due to the fact that the members of that group were opposed to the presentation of a marble bust of General Hernández Martínez. On the other hand, in 1941 he was invited to an education congress in Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States, and in a session dedicated to the Children's literature spoke about the Cuentos de Cipotes that had been being published in national newspapers.

Already in 1942, in the final stage of the «martinato», he resigned from the appointment of secretary of the National Folklore and Typical Art Investigation Committee. Despite everything, in August of that year he finished a mural painting, considered the first in the country's history, at the Eduardo Martínez Monteagudo Municipal School, named after one of the sons of General Hernández Martínez.

During this period, Salarrué won a national painting contest organized by the Rotary Club in 1938, and in 1940 he was awarded a literary prize with the story Matapalo by the newspaper La Nación from Argentina. In addition, an oil painting of his own was selected to represent El Salvador at the Pan-American Union Exposition in April of this year.

Travel abroad and return to El Salvador

In 1946, during the government of Salvador Castaneda Castro, Salarrué was appointed cultural attaché of the Embassy of El Salvador in the United States. In addition, he managed to establish his residence in New York with his family, and not in Washington D.C., which favored him due to the dynamic cultural environment of that city. His economic situation also had some slack with the fees earned.

Precisely, in New York he resumed his passion for painting. In 1947, he exhibited at Knoedler Galleries, which received good reviews from the New York Times, but also in literature he received an honorable mention in Cuba, with the story Toccata y fuga in the international short story contest « Alfonso Hernández Catá". The following year he showed his paintings in San Francisco, and in 1949 he organized a solo exhibition of oil paintings, watercolors and drawings back in New York.

During his stay in the United States, he met Gabriela Mistral again, with whom he strengthened the ties of friendship. He would also maintain a sentimental relationship with Leonora Nichols, part of the New York aristocracy and cultural elite with whom he would exchange letters and poems.

Meanwhile, in 1950 Lieutenant Colonel Óscar Osorio assumed the presidency of El Salvador, who created institutions for cultural promotion that gave impetus to the arts in the country. In those years, some of Salarrué's works were reprinted by the state publishing house, such as The Black Christ, The Lord of the Bubble, and Eso y más, already published in 1940; as well as Trasmallo in 1954, which incorporates the story El espantajo , set in the peasant uprising of 1932. Salarrué returned to El Salvador in 1958 and an exhibition of his pictorial work was organized at the El Salvador Intercontinental Hotel.

On the other hand, in 1960 the Cuentos de Barro were part of the Central American Book Festival collection that consisted of ten volumes and a circulation of 200 thousand copies, launched at the initiative of the Peruvian Manuel Scorza; and the story Matraca was chosen to be published in the international supplement Hablemos magazine in New York, which had international circulation.

In 1961, the University Editorial, directed by Ítalo López Vallecillos, produced the definitive edition of Cuentos de cipotes with illustrations by Zélie Lardé, while later ones would be by her daughter María Teresa who would sign like Maya. The following year, a new exhibition of his paintings was mounted at the Forma de Julia Díaz Gallery, which had been made during his stay in New York. In 1963, Salarrué served as director general of Fine Arts of the Ministry of Education, but resigned due to little support received.

Last years

...that he does not miss the pist or the love necessary |

After retiring from government office, Salarrué lived permanently in Villa Monserrat in Los Planes de Renderos, located south of San Salvador and which he had bought with his savings. The semi-rural environment and the pleasant climate of the area were ideal for the writer to isolate himself. As Sergio Ramírez describes it:

"His theosophical morality...is not only part of that esoteric paraphernalia, but is more deeply based on an ethics that had much to do with his almost claustral way of life, of the last years, priest of his Atlantean mysteries, an irreducible vegetarian, than when he went out into the world from his refuge in the plans of Renderos, on the outskirts of San Salvador, he did it with wonder and wonder. »

However, tributes and acknowledgments came to his person, which he received with some discomfort. On the other hand, those who visited him at his residence would meet a simple, kind, friendly and modest Salarrué.

In 1967, Salarrué rediscovered painting, since he founded and directed the National Art Gallery in Cuscatlán Park, which since 2008 has been known as the Salarrué National Exhibition Hall. In October of that same year, he held a retrospective exhibition at the Centro Cultural El Salvador-Estados Unidos.In addition, since 1973 he worked as cultural adviser to the general director of culture, Carlos de Sola.

Regarding his literary work, several publications were printed in those years: the Obras escogidas with a selection, prologue and notes by Hugo Lindo, which includes the novelette Íngrimo, the stories The Shadow and Other Literary Motives, as well as Vilanos and The Naked Book; Later they would be The thirst of Slig Bader, Catleya Luna and the collection of poems Mundo nomasito. Also in Cuba an anthology of the stories of Salarrué was produced in 1968, edited and prefaced by Roque Dalton.

In 1974 his wife Zélie and her friend Claudia Lars died, both of cancer. According to the painter Ricardo Aguilar, a friend of Salarrúe, to pay for Zélie's treatment they had to pay the doctor with paintings. The same writer also suffered from cancer of the pancreas, and in early 1975 underwent an operation. However, he did not want to face the condition. According to Aguilar, he calmly accepted those last months of life with these words: "If life has given me this, it is because I deserve it and I have to live it and I want to live it." On November 27, he died plunged into the poverty in the bed of his home. It should be added that he refused to receive a pension from the government Despite everything, this condition was not uncomfortable for the artist, who left his judgment in this regard:

"We lived a time when the nobility is diluted between the castes and in which a mind has the permission to enrich and become a purchased greatness. I firmly believe that sustaining poverty with joy is a sign of strength and that it is weak that fears it and cowardly evades it. Poverty awaits enormous wealth in it. Freedom is more feasible in poverty than in opulence. The love that comes to her is always authentic and one knows it."

.

Acknowledgments

In his later years, Salarrué earned various recognitions and distinctions: in 1962 he received the Order of José Matías Delgado in the rank of Commander. The degree of Grand Silver Cross, together with his cousin Toño Salazar and the poet Raúl Contreras, would obtain it in 1973. In November 1967, his artistic work was recognized, together with Claudia Lars and Vicente Rosales y Rosales, by the the Legislative Assembly. A few days apart, the Mexican government awarded him the Benito Juárez National Award together with the folklorist María de Baratta. Two years later he received distinctions from the Salvadoran Academy of Language, together with Claudia Lars. It is said that he refused an honorary doctorate from the University of El Salvador.

Literary works

Writers such as Hugo Lindo and Sergio Ramírez divide Salarrué's work into two spheres: costumbrista and esoteric. The first of them is the one that has had the most diffusion, thanks to the books Trasmallo, Cuentos de cipotes, and especially Cuentos de barro of plot folkloric or reflection of the harsh conditions of the peasant, according to the judgment made of the work. The other theme includes a «theosophical cosmopolis», exposed in texts such as The Lord of the Bubble, Eso y Más and O-Yarkandal, in those that reflect the relationship between good and evil, and how it plays the role of "redeemer" to free others from falling into sin, as well as the existence of astral experiences and mythical worlds.

However, the editor Ricardo Roque Baldovinos makes two important assessments of Salarrué's work. One has to do with the difference between the "classic" costumbrismo, and the salarrueriano. In the former, the literary language is distinguished from the popular one, which belongs to the people and is characterized by being careless, although sometimes nice. Salarrué, on the contrary, makes a synthesis of both styles and experiments with a "stylistic game" that takes indistinctly the cultured and the popular, which ends in a way of "dignifying humble people, of revealing them endowed with sensitivity, artistic capacity".

In the other assessment, Baldovinos points out that Salarrué's traditional and esoteric dimensions are complementary. Both reject both the process of modernization of Salvadoran society derived from the liberal project initiated in the second half of the XIX century; as well as any political doctrine, be it capitalist or communist, whose interests revolve around money, and end up disintegrating the ancestral community represented in the peasant community.

For this reason, Salarrué embraced Theosophy, as did other Latin American figures of the time such as Francisco I. Madero or Augusto César Sandino, along with other Eastern doctrines to face the "crisis of modern society", and find in other beliefs a meaning of life different from the materialist one that dominated the Salvadoran political class. For this reason, it is also affirmed that for the Salvadoran writer art had a deep religious meaning, which served to reestablish the link with the world, broken by the stagnation imposed by Western culture.

Salarrué worked in various fields of literature, such as verse, prose, and essays; and especially the narrative in which he included fantastic stories, adventures and novels. From the years of publication of the most recognized titles, it seems that he stopped writing in the early 1960s. However, there is an undetermined amount of unpublished texts, especially of his lyrical work and also essays scattered in newspapers and magazines, some of them already disappeared. Salarrué's titles that cover his most important narrative creation include (in brackets the year of final publication): The Black Christ (1926), The Lord of the Bubble (1927), O-Yarkandal (1929), Mounting Uluán (1932), Cuentos de mud (1934), Eso y más (1940), Trasmallo (1954), Cuentos de cipotes (1945/61), The sword and other narratives (1962), Íngrimo (1970), The shadow and other literary motifs (1970), The Thirst of Sling Bader (1971), and Catleya Luna (1974). Other publications: Conjectures in the Twilight (essay, 1934); Some poems by Salarrué (poetry, 1971); and Mundo nomasito: una isla en el cielo (poetry, 1975).

In El Salvador he is considered the most important narrator among the writers of that country, as well as one of the precursors of the new Latin American narrative. His work did not go unnoticed in Latin America, as there are letters exchanges and book dedications with the likes of Juan Rulfo, Claribel Alegría, Miguel Ángel Asturias, Rogelio Sinán and Mario Monteforte Toledo.

"I am not concerned that my work is universally recognized. I am interested in being known by my countrymen."Salarrué.

Pictorial work

It is stated that Salarrué considered himself more of a plastic artist than a writer.In this case, his return from the United States coincided with the interruption of his literary work, and the reason was that there was a more conducive environment for exhibiting and sell their paintings in El Salvador. For the experts, Salarrué's paintings, despite covering a vernacular theme, what occupies his works is fundamentally fantasy, a reflection of the mythical world created in O-Yarkandal and Tracing back the Uluán. In this way, there are "meeting points" between his lyrical, sumptuous and tropical prose, and his pictorial work. For the art critic Astrid de Bahamon, Salarrué could be "the first Latin American artist whose abstraction is not influenced by European currents". It is also said that it preceded the psychedelic painting of the 1960s. For Camilo Minero, Salarrué was the "most revolutionary of color".

For Ricardo Lindo, who curated an exhibition of Salarrué's work in 2006, his creations surpass any influence and correspond more to his own "dream world" that in fact had a political structure, landscapes, customs and languages.

"I think there is no painter who does not have a conscious perception of the astral world, because the eye is being done as one works in painting; he becomes able to perceive the color as one sees it directly in the astral world."Salarrué.

Legacy

The Museum of the Word and the Image of El Salvador has guarded Salarrué's personal and artistic archive since 2005. The artist's collection includes 108 pieces of paintings, sketches, drawings and sculptures; 300 pieces belonging to his wife Zelié Lardé and his daughters; photographic record; and personal library of 2,000 titles. The entire legacy was delivered to the Memory of the World Registry of El Salvador, sponsored by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco), on June 6, 2013 in an act that took place at the National Palace of said country, for its official incorporation on November 25, 2016 during the seventeenth annual meeting of the Regional Committee for Latin America and the Caribbean of the UNESCO Memory of the World Program.

Contenido relacionado

Dudley Moore

Theresa Wright

William H Macy