Saladin

Al-Nāsir Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūb (Kurdish: Selahedînê Eyûbî; Arabic: صلاح الدين يوسف بن أيوب), better known in the West as Saladin, Saladin, Salahadin or Saladine (February 2, 1137, Tikrit (Iraq)-March 4, 1193, Damascus), was one of the great rulers of the Islamic world, being sultan of Egypt and Syria and including in his domains Palestine, Mesopotamia, Yemen, Hijaz and Libya. With him began the Ayyubid dynasty, which would rule Egypt and Syria after his death.

Defender of Islam and particularly of the religious orthodoxy represented by Sunnism, he politically and religiously unified the Middle East by fighting and leading the fight against the Christian Crusaders and putting an end to doctrines that were far from the official Muslim cult that the Abbasid Caliphate represented. He is particularly known for having defeated the Crusaders at the Battle of Hattin, after which he reoccupied Jerusalem for the Muslims and took the Holy Land. The impact of this event in the West caused the Third Crusade led by Richard I of England, which became mythical for both Christians and Muslims.

His fame transcended the temporal and became a symbol of medieval chivalry, even to his enemies. He remains a much-admired figure in the Arab, Kurdish and Muslim religions.

Biography

Childhood and youth

He was born on February 2, 1138 in Tikrit, (in the province now called Salah ad Din in his honor, in Iraq), where his father, Ayyub, was governor. His family was Kurdish, originally from Dvin in Medieval Armenia.Like many Kurds at the time, they were soldiers in the service of Syrian and Mesopotamian rulers.

After falling out of favor and being expelled in 1139, his father Najm ad-Din Ayyub and his uncle Asad al-Din Shirkuh, put themselves at the service of Zengi, lord of Mosul and Aleppo, who had united the area under his command northern Syria and Iraq. He was the first of the great Muslim leaders who tried to expel the Crusaders from the Middle East, managing to wrest the County of Edessa from them. Saladin's family then joined his army, his father being rewarded with the government of Baalbek. At that time the Christians would launch the Second Crusade, which would fail.

The violent death in 1146 of the Zengi chieftain sparked a civil war in Syria over the succession. Saladin's family would side with the heir-designate, Zengi's youngest son, Nur al-Din. When after various struggles this prevailed, Saladin's relatives were rewarded: his father received the government of Damascus, and his uncle Shirkuh, the command of the army.

Information about his childhood is scant. Saladin wrote "children are brought up in the way their elders were." According to his biographer, al-Wahrani, he could answer questions about Euclid, the Almagest, arithmetic, law and other academic subjects of his time, but this is an ideal and it was the study of the Qur'an and theology that brought him closest to his goals. contemporaries. Many sources state that his studies were closer to Islamic law and the Koran, typical of a qadi, than conducive to the militia. It is believed that the capture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders in the First Crusade, a great social event of the time, it could influence him morally. He is also reputed to have great knowledge in genealogies, biographies and histories of the Arabs, as well as the lineages of Arabian horses. Saladin knew Abu Tammam's Hamasah by heart.Saladin's military career began under his uncle Shirkuh, a general of Nur al-Din, who took charge of him.

Egypt

Conquest of Egypt

Meanwhile, Egypt was in a period of instability. In the final moments of the Fatimid Caliphate the country was in crisis, threatened by the crusaders, who had occupied Ashkelon and were threatening the border allied with the Byzantines, as well as in civil war by the various aspirants to the position of vizier.

In 1163, the vizier of the Fatimid caliph al-Adid of Egypt, Shawar, had been expelled from the country by his rival Dirgham, of the powerful Banu Ruzzaik tribe. His request for military aid from Nur al-Din led to Shirkuh being sent against him in 1164. Saladin, then a 26-year-old youth, marched with him. After reinstating Shawar as vizier, he demanded the withdrawal of Shirkuh's army in exchange for thirty thousand dinars, but was denied at the Syrian sultan's wish that his troops remain in the country. Shawar then sought the support of the King of Jerusalem, Amalric I. Saladin's role in this campaign was minor but it is known that he was given the mission of gathering provisions for Bilbais before his siege by a force of crusaders and Shawar loyalists.

After the sack of Bilbais, the combined force and Shirkuh's army engaged in a battle in the desert along the Nile River east of Giza. Saladin was an outstanding leader here, commanding the right wing, while Kurdish troops made up the left and Shirkuh personally commanded the center. Muslim sources, however, put Saladin at the center, with orders to lure the enemy into a trap through a mock withdrawal. Either way, the initial Crusader success crashed into the harsh, steep and sandy terrain for horses, and Hugh of Caesarea, a Christian commander, was captured attacking Saladin's unit. After a fight in the narrow valleys to the south, the Zenguid army returned to the offensive, Saladin joining in from the rear.

The battle ended in victory for Nur al-Din's troops, and Saladin gained fame for having assisted the veteran general Shirkuh in one of his "most memorable victories in recorded history", according to Ibn al. -Athir, despite the fact that his own troops had suffered heavy casualties and it was not a clear victory. Shirkuh and Saladin went up to Alexandria, where they were enthusiastically received and obtained money, weapons, and a base. Faced with a superior Crusader-Egyptian force trying to besiege the city, Shirkuh divided his troops, withdrawing from Alexandria, leaving it in the hands of of his nephew. An attack by Nur al-Din from Syria against the Crusaders forced Amalric to lift the siege to defend his domains in the North, reaching a peace in exchange for the withdrawal of Shirkuh and Saladin from Egypt.

Shirkuh, disappointed with this result, continued to prepare for the conquest of Egypt, with Shawar suspicious of Syrian intentions and renewing his alliances with Amalric. In late 1166 and early 1167 Shirkuh, again accompanied by Saladin, again invaded Egypt with the blessing of Nur al-Din and opposition from Shawar and Amalric loyalists. Shirkuh managed to avoid confrontation with the Crusaders on his way south. In March 1167, finally, the allies managed to force a battle that Shirkuh won, although with heavy losses on both sides. Shirkuh marched to Alexandria, with a Sunni majority and where they enjoyed wide support. As in 1163, Shirkuh departed leaving Saladin in charge of him trying to avoid being caught up with the bulk of his army. Saladin soon found himself involved in another harsh siege while Shirkuh lay idle, attacking neither the besiegers nor his base in Cairo. It seems that in the end a treaty was negotiated between Shirkuh and the allies where again Amalric and Shirkuh would leave the country in exchange for compensation and with guarantees of amnesty for the population of Alexandria that had sided with Saladin. Saladin personally remained in the Crusader camp during negotiations to secure guarantees for Alexandria.

Beset by internal problems due to the unpopularity of his alliance with the Christians, Shawar went on to negotiate with Nur al-Din to prevent Shirkuh from attacking Egypt again. However, he himself was betrayed when Amalric attacked Egypt in 1168. He soon captured Bilbais, which had resisted him in 1163, and destroyed the town in November. He then marched on Fustat, the official capital, before Shawar had time to gather his forces. force. The vizier then decided to burn the city, in a scorched-earth strategy before it could be used as a base against Cairo, the Caliph's residence and de facto capital. Amalric besieged it anyway. With the enemy at the gates, al-Adid appealed to the Sultan of Syria for help, who again sent Shirkuh. It seems that he had a hard time convincing Saladin to accompany him because of the bad memory of the sites of Alexandria and Bilbais. In December 1168, however, Saladin was with the rest of the army in Egypt. News of his arrival forced a truce with Amalric in January 1169, where again the Egyptians paid for his withdrawal to Jerusalem. With al-Adid's approval, Shirkuh and Saladin entered Cairo unopposed. Saladin personally arrested Shawar, who was sentenced to death by the caliph, Shirkuh was given the title of vizier, and Saladin was given a government post by him.

Lord of Egypt

By 1169 Shirkuh controlled the country, acting partly as prime minister of the Fatimid Caliph of Egypt, partly as governor and representative of the Syrian Sultan. In March of that same year he died, Saladin being chosen as his successor. The cause of his appointment is uncertain: the hypotheses vary from an election of the Syrian emirs to an election of the caliph to divide the occupiers between Kurds and Turks. Nur al-Din had chosen a replacement, but al-Adid and the local emirs managed to impose Saladin as vizier The reasons for a Shia caliph like al-Adid to support a Sunni are uncertain. According to Ibn al-Athir, his advisers told the caliph that "there was none weaker or younger" among the candidates and that "no emir would obey him", but according to the same version he was accepted by the majority of emirs after a little negotiation. Al-Wahrani wrote that he was chosen because of his family's reputation, which was considered generous and courageous. Imad al-Din said that after a brief period of mourning with "conflicting opinions", the Zenguid emirs chose him and forced the caliph to appoint him. Although his position was probably disputed, it is generally agreed that his record in previous campaigns with his uncle gave him an impeccable resume among the emirs.

Inaugurated as vizier on March 26, Saladin was transformed. He gave up drinking alcohol, which despite religious taboos was common in the military, and became more religious. Having gained more power than ever in his career, he was faced with the dilemma of the division of loyalties between his two lords, al-Adid and Nur al-Din. The second was rumored to be secretly hostile to him. Nur al-Din knew little of his general's nephew, other than that he was from the ambitious Ayyubid family, and went so far as to state "how will he do anything without my orders?" Saladin ignored various letters from the Syrian sultan without rejecting his authority.

As ruler he faced a state as unstable as in Shawar's time, with the added bonus of being a foreign regent and the split between the Shiite caliph and his personal Sunnism. The challenge was made worse by having to face the delicate situation under the scrutiny of the Syrian sultan, who craved direct control of Egypt, and the cross threat.

Saladin clashed from the outset with the Fatimid elites, who feared that the Sunni vizier would end the caliphate as he did. A plot against Saladin took place almost immediately, in 1169, centering on the black eunuch who served as the caliph's steward. Saladin learned of the plot and executed the eunuch while he was outside the city inspecting his property. This execution triggered a rebellion the next day by black military units numbering around 50,000 strong, who were the backbone of the Egyptian army. and the most loyal to the Fatimids. Saladin put down the revolt and restructured the army based on his Syrian troops (Kurdish and Turkish, primarily) instead of the Maghreb mercenaries that was normal in the country. In this way, he not only created a more experienced and prepared army, but also guaranteed personal control over it. He never again had to face a revolt against Cairo. It was not the only challenge he had to overcome in 1169. Amalric returned supported by the Byzantine army, which stormed Damietta. Luckily for Saladino, the division between the attackers was clear and they had to withdraw.

Although he did not eradicate the Fatimid caliphate until 1171, Saladin actively tried to promote Sunnism as vizier. He founded several mosques and madrasas to spread the Sunni ideology, which was very popular since it was the mainstream in the country despite not being the official one. The systematic appointment of Sunni jurists to the judiciary guaranteed his control of the administration and the state. In Cairo he ordered the construction of a university for the Malikí branch and another for the Shafi'i (to which he himself belonged). in Fustat. The reduction of bureaucracy allowed him to eliminate some taxes and fees, which bordered on the Muslim concept of usury, which was widely accepted. Another feature of his government was the incorporation of part of the Egyptian elite into his administration. He stands out above all Qadi al-Fadil, a brilliant jurist from Ashkelon who had served Shawar and Shirkuh. Such men gave Saladin contact with the complex circles of economic and social power of the Fatimid empire. Furthermore, his tolerance and pragmatism earned him the support of Jews and Copts, key players in the banking system and vital to the Egyptian economy.

By 1170, Saladin had secured a secure position in the country. It was of great help to him that he managed to get his family to join him (mainly his father, Ayub), with whom he created an administration linked to him. Meanwhile, Nur al-Din pushed for the deposition of the caliph, Saladin tested the caliph with acts such as riding into his court (which only the caliph could do).

Without internal opposition, he was free to carry out attacks against the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1170. He besieged the city of Darum to no avail, causing Amalric to withdraw the Templar garrison from Gaza to defend it. Saladin evaded them and ravaged Gaza. He only left the fortress, but massacred those who had not taken refuge in it. The same year he managed to take the city of Eilat and the neighboring island of Pharaoh, in the Red Sea, which without being a great threat allowed the crusaders to harass the fortress. navigation near Sinai. According to chronicles, towns such as Amman were under Saladin's control while the Crusaders retained their castles and strongholds in Transjordan, hindering a real connection between Syria and Egypt.

Saladin withdrew early from the campaign of 1171, where he was supposed to participate in a joint assault with Nur al-Din on the Krak of Knights, in part to avoid confronting his lord. Nur al-Din got angry with Saladin for it. To test him and please the Abbasid Caliphate, he ordered him to dissolve the Fatimid Caliphate in June 1171. Saladin then faced the risk of further revolts, so he waited for al-Adid's death, which seemed imminent (in fact, it is suspected that he could have been poisoned) to officially end the caliphate. His death on June 17, 1171 marked the definitive reintegration of the cult in Egypt to the Sunni current, the majority in Islam, during the occupation and command of Saladin. The biggest sign of this was five days later, the Friday prayers being performed in the name of the Caliph of Baghdad, al-Mustadi. This enhanced his prestige within the Islamic community, which was still badly affected by the fall of the city. Holy Jerusalem in the hands of the Crusaders in 1099.

Sultan of Egypt

After Al-Adid's death he was in theory a vassal of Nur al-Din but in practice he was the de facto governor of Egypt: he recognized the authority of the Sultan of Syria, but enjoyed complete independence in his rule of Egypt, due to the distance between Damascus and Cairo, separated by states ruled by the European Crusaders. The withdrawal from the campaign against Karak is normally seen as a show of independence. Saladin probably feared that seeing Nur al-Din would prevent him from returning to Egypt, fearful of the control he already had of the country. It was also possible that if they then attacked the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which acted as a buffer state, it would have disappeared, leaving Saladin alone in front of the Syrian, who would then have had the pretext to seize power over Egypt. Saladin alleged Fatimid conspiracies behind him, but Nur ad-Din did not accept "the excuse."

A family council of 1171-1172 already shows the independence of Saladin. Advised by his emirs, Saladin decided to send his nephew al-Muzaffar Taqi al-Din Umar, to occupy the Cyrenaica region (in the border area of the Gulf of Sirte) under the command of 500 horsemen. For this, he sent an ultimatum to the Berber tribes of the area that demanded the return of goods stolen from travelers and subjected them to the payment of taxes (zakat ), which would be extracted from their cattle.

During the summer of 1172, a Nubian army, accompanied by Armenian refugees and former Fatimid soldiers, was sighted on the border preparing a siege against Aswan. The emir of the city, Kanz al-Dawla, asked Saladin for reinforcements, who sent his brother Turan-Shah. Egyptian forces prevailed, but the Nubians returned in 1173. This time the Egyptians launched a counterattack that led to the capture of Ibrim and the conquest of northern Nubia. From Ibrim, Turan-Shah ravaged the region obtaining an armistice from Dongola. Peace implied the Nubian commitment to guarantee the security of Aswan, rejecting the idea of continuing further south due to the poverty of the area.

Nur al-Din demanded the return of the two hundred thousand dinars spent on Shirkuh's army. Saladin sent sixty thousand dinars, "wonderful Egyptian artifacts," jewelry, a fine donkey, and an elephant. During the trip to Damascus to deliver the presents, he marched across crossed lands. He did not take the castles in the desert, but attacked the Muslim Bedouin who served as their guides.

Meanwhile, the conquest of Libya continued. In 1174, Sharaf al-Din Qaraqush, Taqi al-Din's lieutenant, seized Tripoli, which had been occupied by the Normans under the command of a Turco-Bedouin force. zone between Saladin's freedman, Karakush, the nascent Almohad Empire and the remnants of the Almoravid Empire.

On July 31, 1173, his father, Ayub, was wounded after falling from his horse, killing him on August 9. The loss of his faithful vassal added to Nur al-Din's misgivings.

In 1174, Saladin sent Turan-Shah to conquer Yemen and the surrounding areas of the Red Sea. The excuse was that these territories did not recognize the Caliph of Baghdad, being for the majority of Muslims heretics, but authors such as al-Maqrizi or Ibn al-Athir usually consider that Saladin prepared a safe place to which he and his family could flee in the event of an attack. of Nur al-Din. The Kharijite ruler of Zabid, Mahdi Abd al-Nabi, was executed in 1174 and the port of Aden was seized from the Banu Karam Shi'a tribe soon after. Turan-Shah also drove the Hamdanids out of Sana'a in the mountains in 1175..

It was a historic moment for Yemen, which for the first time saw its hitherto independent cities of Aden, Sanaa and Zabid united. Aden was the main Indian port of the kingdom of Saladin, although the government of the province was exercised from Ta'izz. The arrival of Saladin's government brought renewal to the city, which saw improvements in its infrastructure, the creation of new institutions and its own mint. The conquest, in addition to a rear guard, gave it maritime control of the Red Sea, for which it created a coastal fleet, al-asakir al-bahriyya, in charge of monitoring the piracy. The sea was a rich commercial area that included Yanbu and the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, of great psychological and propaganda value. To favor trade, coastal infrastructures were built. The conquest of Yemen thus also helped to revitalize Egyptian trade. However, Saladin still faced further revolts after the return of Turan-Shah and it was not until the appointment of his other brother Tughtekin Sayf al-Islam as governor in 1182 that the conquest of the country was consolidated.

Sultan of Syria

Conquest of Damascus and southern Syria

In the early summer of 1174, Nur al-Din was apparently preparing an attack on Egypt, having sent requests for troops to Mosul, Diyarbakir, and al-Jazira. The Ayyubid family held a council on how to deal with this possible threat, and Saladin assembled his troops outside Cairo. However, on May 15, Nur al-Din died. His eleven-year-old son as-Salih Ismail al-Malik remained in power. With this, Saladin obtained de facto total independence; in a letter to his heir, she promised to "act like a sword against his enemies" and defined the death of his father as "the shock after an earthquake."

The death of Nur al-Din left Saladin with a difficult decision. He could attack the Crusaders from Egypt or wait until invited by as-Salih in Syria to attack from there. He could also occupy Syria before, as it seemed, it fell into the hands of a rival, but he feared the moral hypocrisy of attacking the lands of his former lord, something abhorrent due to his Islamic morality and which made him unable to lead the war against the crusaders. In order to annex Syria he needed an invitation from as-Salih or an excuse such as the potential danger crossed in a case of misrule.

When as-Salih was brought to Aleppo in August, the regency was assumed by Gumushtigin, the emir of the city and captain of Nur al-Din. The emir prepared to unseat his rivals, beginning with Damascus. Faced with these prospects, the emir of the city went to Saif al-Din (Gumushtigin's cousin) of Mosul for support, but was rejected and had to go to Saladin. Saladin crossed the desert with 700 horsemen, passed through Kerak and reached Bozrah. He was followed by "emirs, soldiers, Turks, Kurds, and Bedouins on whose faces the emotions of their hearts were visible". On 23 November he arrived in Damascus to cheers and rested in his father's old house in the city, until he died. they opened the doors of the Citadel of Damascus, where he settled and received the homage of the citizens.

Aleppo and Northern Syria

Leaving his brother Tughtigin as governor of Damascus, Saladin moved north to subdue other cities that had once belonged to Nur al-Din's empire but had become quasi-independent after his death. He took Hama without much trouble, but bypassed the powerful fortress of Homs. He then moved towards Aleppo, which he besieged on 30 December 1174 after Gumushtigin refused to relinquish the throne. But as-Salih, who feared Saladin, left the palace and asked the population not to surrender.

Look at this unjust and ungrateful man who wants to take away my country without consideration for God or for men! I am an orphan and I count on you to defend myself in memory of my father who loved you so much.as-Salih al-Malik

One of Saladin's chroniclers said that "the people fell under his spell".

Gumushtigin asked for help from Rashid ad-Din Sinan, great master of assassins, a sect that was at enmity with Saladin (it is a Fatimid current, which had seen the end of the Egyptian caliphate with great anger). They planned to assassinate Saladin in his camp, a group of 13 assassins easily entered it, but were detected before committing the crime. One fell to a Saladin general and the others were overpowered as they tried to flee.To further complicate matters, Raymond III of Tripoli assembled his forces at Nahr al-Kabir near Muslim territory. He faked an attack on Homs, but withdrew after hearing that Saif al-Din was sending reinforcements.

Meanwhile, Saladin's enemies in Syria and Mesopotamia waged a propaganda war, based on the idea that he "had forgotten his vassal status" and showed no gratitude for his former lord by besieging his son "in rebellion." against his master." Saladin tried to counter this propaganda by lifting the siege and claiming that he was defending Islam against the Crusaders. He returned with his troops to Hama to face a Crusader army, which withdrew allowing Saladin to proclaim "a victory that opened the gates of men's hearts". Shortly afterwards he managed to enter Homs and take its citadel (March 1175). despite stubborn resistance from the defenders.

Saladin's successes alarmed Saif al-Din. Head of the Zenguids, including Gumushtigin, viewed Syria and Mesopotamia as his land and was angry at "Saladin's usurpation". Saif al-Din assembled a large army and marched with it to Aleppo, where the defenders eagerly awaited him. The combined forces of Aleppo and Mosul marched against Saladin at Hama. Severely outnumbered, Saladin negotiated to abandon the lands north of Damascus, but no agreement was reached. The Zengids wanted his return to Egypt. Confrontation being inevitable, Saladin took advantageous positions on the hills of the Orontes River. On April 13, 1175, the Zénguids marched against him, but were soon surrounded by more veteran and better positioned troops, who annihilated them. The battle was a decisive victory for Saladin who pursued the fleeing army to the gates of Aleppo, forcing as-Salih's advisers to recognize his rule not only of Damascus, but of Homs, Hama and cities closer to Aleppo such as Maarat. an-Numan or Baalbek.

Following his victory, Saladin proclaimed himself king and removed as-Salih's name from the Friday prayer and from coins. Since then, he was to be prayed for in all the mosques of Egypt and Syria and a coin to be minted in Cairo bearing his name, al-Malik an-Nasir Yusuf Ayyub, ala ghaya ('the strong king in help, Joseph son of Job, praised be'). The Abbasid Caliphate recognized his self-granted authority and declared him "sultan of Egypt and Syria".

This battle of the Horns of Hama did not, however, end the power struggles between the Ayyubids and the Zenguids. The final confrontation lasted until the spring of 1176. Saladin brought troops from Egypt while Saif al-Din levied between the vassal states of Diyarbakir and al-Jazira. When Saladin crossed the Orontes, leaving Hama, there was an eclipse of the sun. Despite seeing it as an omen, he continued the march, reaching the Sultan's Tumulus, 24 km from Aleppo. There his forces met Saif al-Din's army. A hand-to-hand fight ensued, where the Zenguids managed to get past Saladin's left wing before he personally charged the Zenguid guard. At this attack the Zengids broke into a panic, most of the officers being killed and Saif al-Din narrowly escaping. The Zenguid camp with its horses, baggage, tents, and provisions were captured. Saladin, however, freed his prisoners with gifts and divided the booty among his army without keeping anything for himself.

He continued against Aleppo, which received him with closed doors. On the way he had taken Buzaa and Manbij. From there he headed east to besiege the fortress of Azaz on May 15, 1176. A few days later, with Saladin resting in a tent, an assassin entered, striking him over the head with a knife. His armor helmet saved him and he managed to grab the assassin by the hand thanks to wearing his gambeson. The murderer was executed and Gumushtugin and the Nizaris accused of the attack, reinforcing the siege of the city.

Azaz surrendered on June 21, 1176, and Saladin rushed his troops to Aleppo to punish Gumushtigin. His assaults were repulsed but he not only managed to sign a truce but even an alliance pact with Gumushtigin and as-Salih that in exchange for keeping the city recognized Saladin for everything he had conquered. The emirs of Mardin and Keyfa, allied with Aleppo, also recognized Saladin as the lord of Syria. After the signing of the treaty, the little sister of as-Salih went to Saladin demanding the return of the fortress of Azaz. Saladin agreed and escorted her back to Aleppo with numerous gifts.

Campaign against assassins

Taking advantage of his truces with the Zengids and the Crusaders, Saladin embarked in the summer of 1175 on a campaign against Sinan's assassins. As soon as he received troops from Egypt, Saladin moved against his strongholds in Lebanon, but withdrew that same month without having conquered any. Many Muslim historians claim Saladin's uncle brokered a peace treaty between him and Sinan, however propagandists for the assassins claim Saladin resigned out of fears for his own life. He had ordered chalk and sand left around his tent at the Masyaf site so that he could see the tracks of possible assassins and given torches to his guards.

According to this version, one night the guards saw an explosion and something disappearing among the tents. Saladin awoke from his dream in time to see a figure leaving his tent. He noted that the lamps were displaced and that the bed had marks like those of the peculiar weapons of the assassins with a note stuck in a poisoned dagger that warned him that he would be killed if he did not withdraw from the assault. Saladin shouted, claiming that the figure had been Sinan himself, and ordered his guards to come to terms. Realizing the impossibility of taking his fortresses dug into the mountains, he preferred to come to terms and prevent the Crusaders from using them. as a secret weapon.

Fight with the Christians

After leaving the al-Nusayri mountains, Saladin returned to Damascus and discharged his Syrian troops. He left his brother Turan Shah in charge of Syria and marched on Egypt with his personal court, reaching Cairo on September 22. After two years away, he had a lot to supervise in the Nile country, particularly works and projects that he had left behind in Cairo. He repaired and expanded the city walls and began the construction of the Cairo Citadel.He also ordered the construction of the 85-meter Bir Yusuf shaft. His greatest public work outside the city was a great bridge at Giza, which was intended to facilitate defense against Moorish invasions.

Saladin remained in Cairo supervising his rule and building the Madrasa of the Sword Makers. In November 1177, he launched a raid on Palestine. The crusaders had penetrated the territory of Damascus and Saladin took the truce as something that he no longer had the courage to preserve. The Christians sent a large portion of their army to besiege Harem, en route from Christian Antioch to Aleppo, neglecting its southern border. Saladin believed the occasion was ripe and marched against Ascalon, which he called the "bride of Syria." ». William of Tire records that the Ayyubid army consisted of 18,000 black slaves from the Sudan and 8,000 Turkmen and Kurdish elite soldiers. The army ravaged the countryside, sacked Ramla and Lod, and reached the gates of Jerusalem.

Saladin allowed King Baudouin to enter Ashkelon with the Knights Templar from Gaza without taking precautions against a surprise attack. Although the crusaders only had 375 knights, Saladin hesitated to ambush them in the presence of veteran troops and experienced officers. On November 25, 1177, with the bulk of his army absent from him, Saladin and his troops found themselves surprised at Tell Jezer, near Ramallah. Before they could form into battle order, the Templars broke their lines. Saladin initially tried to organize his men, but upon the death of his guard he saw defeat inevitable and with the few remaining troops he rode a camel to Egypt. In Christian chronicles it is known as the Battle of Montgisard.

Undaunted by his defeat at Tell Jezer, Saladin prepared to fight the Crusaders again. In the spring of 1178, he was encamped under the walls of Homs while skirmishes took place between his generals and the crusaders. His troops in Hama won a battle and brought the spoils of the enemy, with many prisoners, to Saladin, who ordered his beheading to "wash the lands of the Believers of rubbish." He spent the rest of the year in Syria, without fighting his enemies.

Saladin's spies informed him that the crusaders were planning an expedition into Syria. The sultan ordered his general, Farrukh-Shah, to patrol the Damascus border with a thousand soldiers waiting for an attack to withdraw without a fight and warn with torches on the hills for Saladin to march. In April 1179, crusaders led by Baldwin, who expected no resistance to his surprise attack on the eastern Golan Heights, began the expedition. They advanced too quickly in pursuit of Farrukh-Shah, who was concentrating his troops south-east of Quneitra, and were defeated by the Ayyubids in what is known as the Battle of Maryayun. With the victory, Saladin brought reinforcements and requested fifteen hundred horsemen from his brother al-Adil in Egypt.

In the summer of 1179, Baldwin had built an outpost on the road to Damascus and intended to fortify a pass across the Jordan River, known as Jacob's Ford, which controlled access to the plain of Banias, divided between Muslims and Christians. Saladin offered Baldwin one hundred thousand gold pieces in exchange for abandoning the project, particularly offensive for being a holy place for Muslims, but there was no deal. He thus resolved to destroy the fortress and moved his headquarters to Banias. As the Crusaders rushed to attack his forces, they lost their formation. After initial success, they pursued the enemy until they lost all order and were overwhelmed by Saladin's troops. This Battle of James's Ford and the capture of the fortress on August 30, 1179 was a key victory for Saladin.

In the spring of 1180, while Saladin was in the vicinity of Safad, hoping to start a new campaign, Baldwin sent messengers with proposals for peace. After droughts and bad harvests, he was short of provisions and accepted. Raymond III of Tripoli opposed the truce, but a raid on his land and the sight of Saladin's fleet at Tartus convinced him.

Islamic leader

Peacetime Diplomacy

In June 1180, Saladin received Nur al-Din Muhammad, the Orthoqid emir of Keyfa at Geuk Su, presenting him and his brother, Abu Bakr, with gifts worth one hundred thousand dinars, according to Imad al-Din. He thus tried to establish an alliance with said dynasty and impress other emirs of Mesopotamia and Anatolia. He also offered to mediate between him and Kilij Arslan II, Seljuk Sultan of Rum, who was claiming the lands he gave her as a dowry for her daughter that she had complained about the treatment of her husband. Nur al-Din asked Saladin for help, but Arslan did not accept him as a mediator.

Following the meeting with Nur al-Din, the most powerful of the Seljuk lords, Ikhtiyar al-Din al-Hasan, obtained Arslan's submission, forcing an agreement. Saladin received a message from Arslan shortly after complaining of further abuse of his daughter, enraging him. Saladin's response was to threaten to attack Malatya, two days' march away, without getting off his horse until he entered the city. Frightened by the ultimatum, the Turks negotiated. Saladin felt that Arslan was doing the right thing in caring for his daughter, but he could not abandon a vassal who had asked for his protection and betray him. The final agreement gave the woman a year away from her husband's home and Saladin's commitment to abandon Nur al-Din if he breached the deal.

Leaving Farrukh-Shah in charge of Syria, Saladin returned to Cairo in early 1181. According to Abu-Shama, he intended to fast Ramadan in Egypt and then make the pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj). For unknown reasons he changed his mind and it is known that he personally inspected the banks of the Nile in June. He confronted the Bedouin, who were dispossessed of two-thirds of their land with which he rewarded the Fayoum peasants whose property he had confiscated. The Bedouins were accused of trading with the Crusaders, their grain confiscated, and forced to settle further west. The Egyptian fleet also engaged Bedouin pirates at Lake Tanis.

In the summer of 1181, Saladin's eunuch and administrator Karakush led the arrest of Majd al-Din—a former lieutenant of Saladin's brother Turan-Shah in Zabid, Yemen—while entertaining Imad al-Din at his own expense in Cairo. Those close to Saladin accused him of misappropriating Zabid's profits, but Saladin himself said there was no proof. He acknowledged the mistake and released Majd al-Din in exchange for compensation of 80,000 dinars and other sums to Saladin al-Adil's brothers and Taj al-Muluk Bari. It is one of several episodes in Turan-Shah's controversial march from Yemen. Although his lieutenants continued to send him benefits from the province, leadership was lacking and fighting broke out between the Izz al-Din Uthman of Aden and the Hittan of Zabid. Saladin wrote in a letter to al-Adil:

Yemen is a treasure house... we conquer it, but until this day we have had no benefits or advantages of it. There have only been countless expenses, shipments of our troops... and expectations that were not satisfied at the end.

Conquest of Mesopotamia

The main Zenguid prince, Saif al-Din, died in June of that year, succeeded by his brother Izz al-Din in Mosul. On December 4, the son of Nur al-Din and theoretical head of the as- Salih died after having made his officers swear allegiance to Izz al-Din, in an attempt to create a zenguid power that could compensate Saladin. Izz al-Din was welcomed in Aleppo, but the government's expectations of him as leader of the dynasty surpassed him and he exchanged Aleppo for Sinjar to his brother Imad ad-Din Zengi. Saladin did not offer any opposition in respect to the peace treaties with the family.

On May 11, 1182, Saladin with half his army and numerous non-combatants marched from Cairo to Syria. On the night before his departure, he sat with the tutor of one of his sons who quoted a verse: "enjoy the perfume of the Nechd bull's-eye plant, after this afternoon he will not come." Saladin saw in it an evil omen and never saw Egypt again Knowing that the crusading forces were massing to intercept him, he crossed the desert from the Sinai peninsula to Eilat and the Gulf of Aqaba. Meeting no opposition, he plundered the Montreal countryside, while Baudouin's forces stood watch without intervening.He arrived in Damascus in June to discover that Farrukh-Shah had attacked the Galilee, sacking Daburiyya and taking Habis Khaldek, a fortress of great importance. In July, he was tasked by Saladin to attack Kawkab al-Hawa, where he fought the Battle of Belvoir Castle, which resulted in a draw. Later in August a land and sea attack on Beirut for which he built 30 galleys was launched, which was about to fail when Saladin withdrew to focus the occasion in Mesopotamia.

Kukbary, who ruled in Harran invited Saladin to occupy the region of Jazira, in northern Mesopotamia. Saladin accepted and terminated the truce with the Zengids in September 1182. Before his march to Jazira, internal fighting had broken out among the Zengids, many of whom did not want to recognize any primacy to Mosul. Before crossing the Euphrates River Saladin besieged Aleppo for three days, thus declaring the end of the truce.

Once they reached Bira, on the bank of the said river, Kukbary and Nur al-Din joined him; their combined forces took first Edessa, then Saruj, and then Raqqa. Raqqa was an important crossroads defended by Qutb al-Din Inal, who had lost Manjib to Saladin in 1176 and surrendered to Saladin's huge army in exchange for keeping his property. Saladin impressed the city's inhabitants by issuing a decree eliminating various taxes and striking them off the records because "the most miserable rulers are those who are fat while their people are thin." From Raqqa he moved successively conquering al-Fudain, al-Husain, Maksim, Durain, Araban and Khabur, who swore allegiance to him. His conquests continued through Karkesiya and Nusaybin. Saladin took Nusyabin without meeting resistance. Medium in size, it was not very important, but it had a strategic position between Mardin and Mosul and was close to Amid (Diyarbakır).

In the midst of these conquests, Saladin was informed that the crusaders were looting the villages in the Damascus region. His reply was: "Leave them... while they are destroying villages we are taking cities, when we return we will have more forces to fight with them." While in Aleppo, the city's zenguid emir sacked cities loyal to Saladin such as Balis, Manbij, Saruj, Buzaa or al-Karzain. He also destroyed his own citadel at Azaz to prevent the Ayyubids from using it against him.

Trouble in the Red Sea

On March 2, 1182, at the truce in his Syrian campaign, al-Adil wrote a letter from Egypt to Saladin informing him that the crusaders had attacked "the heart of Islam." Raynald of Chatillon, a controversial and violent border lord had sent ships from the Gulf of Aqaba to plunder the Red Sea coast. Eilat was reoccupied although the Pharaoh's Island garrison held on. This was not an attempt at conquest, but mere piracy. Imad al-Din writes that the attack alarmed the Muslims, who were not used to such attacks on a sea they completely controlled, and Ibn al-Athir adds that the The inhabitants had no experience with the Crusaders, either as enemies or as merchants.

According to testimonies reported by Ibn Jubair, sixteen Muslim ships were burned by the Crusaders, who captured a ship with pilgrims in Aidab. He also narrates that they planned to attack Medina and take the body of the Prophet Muhammad. Al-Maqrizi writes that they wanted to take him to Christian territory to force Muslims to make pilgrimages there. Fortunately for Saladin, al-Adil had led his fleet from Fustat and Alexandria to the Red Sea under the command of an Armenian mercenary named Lu'lu. They broke through the Crusader blockade, destroying most of their ships, and pursued those who dropped anchor and fled into the desert. The survivors, 170 in all, were executed on Saladin's orders in various Muslim cities.

Fight for Mosul

As Saladin neared Mosul, he was faced with the problem of taking a large city and justifying the conquest. The Zengids of Mosul appealed to an-Nasir, the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad whose vizier was favorable to them. An-Nasir sent Sheikh al-Shuyukh (a high-ranking figure) to mediate. Saladin arrived before the city walls on November 10, 1182. Izz al-Din did not accept his terms, which he saw as out of proportion, and Saladin immediately laid siege to the heavily fortified city.

After several minor skirmishes, a stalemate was reached, promoted by the caliph. Saladin tried to withdraw without suffering damage to his image and keeping pressure on Izz al-Din. He decided to attack Sinjar, defended by Izz al-Din's brother, Sharaf al-Din. The city fell after a 15-day siege on December 30. The Ayyubid forces lost order, sacking the city. Saladin only managed to protect the governor and his officers by sending them to Mosul. After establishing a garrison in the city, he awaited the arrival of a coalition from Aleppo, Mardin and Armenia, Saladin awaited them with his army at Harran in February 1183, but as he advanced they sent messengers to Saladin requesting peace.. Each army returned to their cities and al-Fadil wrote "[a]dvancing like men, vanishing like women" in reference to Izz al-Din's troops.

From Saladin's point of view the war was going well. He had managed to conquer vast territories, but he had not achieved the goal of taking the city. His army, however, was dwindling; Taqi al-Din led his men back to Hama while Nasir al-Din Muhammad and his forces left. This encouraged Izz al-Din and his allies who resumed the offensive. The coalition met at Harzam, north of Harran. In early April, without waiting for Nasir al-Din, Saladin and Taqi al-Din advanced against them, marching east to Ras al-Ein without difficulty. In late April, after three days of "real fighting" according to Saladin, the Ayyubids captured Amid (Diyarbakır). He handed over the city to Nur al-Din Muhammad with his provisions (80,000 candles, a tower full of arrows and 1,040,000 books). In exchange for the city, he swore allegiance to him and promised to follow him in his campaigns as well as to restore the city. The fall of Amid also convinced Il-Ghazi of Mardin to go over to Saladin's side, further weakening Izz al-Din. Other towns that went over to the Ayyubid side in 1182 include Maras.

Saladin tried to justify his campaigns against Izz al-Din to Caliph an-Nasir and asked him for legal justification to occupy Mosul. Saladin recalled that while he had returned Egypt and Yemen to the authority of the Abbasid Caliphate, the Zengids of Mosul relied on the Seljuks, the Caliphate's rivals, and only turned to an-Nasir when they needed him. He also blamed Izz al-Din for avoiding "holy war" against the Crusaders, stating that "not only do they not fight, but they prevent those who can from doing so." He justified his conquest of Syria by fighting the Christians and the murderous heresy. He promised that if Mosul was handed over to him, he would seize Jerusalem, Constantinople, Georgia, and the Almohad Empire (which also did not recognize the Caliph of Baghdad) for Islam until "the word of God is supreme and the Abbasid Caliphate has cleansed the world, converting churches." in mosques." He said that this would happen by the will of God and that in exchange for the caliphate's support he would give him Tikrit, Daquq, Khuzestan, Kish and Oman.

Submission of Aleppo

Saladin then turned his attention to Aleppo. He sent his brother Taj al-Mulk Buri to take Tell Khalid, 130 km north of the city. Although a siege was started, the governor surrendered before the arrival of Saladin on May 17, 1183, without a fight. According to Imad al-Din, after this capture he marched on Ain Tab, which was occupied by his armies before proceeding to Aleppo. On May 21 he was encamped in front of his walls, east of the Citadel of Aleppo while his forces surrounded the suburbs of Banaquso to the north and Bab Janan to the west. His troops, expecting easy success, boldly approached the walls.

Zangi offered no long resistance. He was unpopular and personally longed to return to his former domain in Mesopotamia. An agreement was negotiated whereby he handed over Aleppo to Saladin in exchange for returning to Sinjar as Saladin's vassal and governor. His administration would reach as far as Nusaybin and Raqqa and he would have to pay allegiance and participate in Saladin's army. On June 12, 1183, the city was formally handed over to the Ayyubids. The people of Aleppo, unaware of these schemes, were surprised by the raising of Saladin's banner in the citadel. Two emirs, including Saladin's personal friend, Izz al-Din Jurduk, welcomed him and offered his allegiance. Despite his promises not to interfere in the religious government of the city, he replaced the Hanafi judges. Saladin allowed Zangi to leave with all the provisions from the citadel that he could carry and sell the rest, which Saladin bought.

Despite his initial reluctance to exchange, Saladin had no doubt that "Aleppo was the key to those lands [since] this city is the eye of Syria and its citadel its ward." For Saladin the capture of the city marked the end of eight years of waiting since he told Farruj-Shah "We just have to milk and Aleppo will be ours." From his new stronghold, he could now threaten the entire Crusader coast.

After spending a night in the citadel of Aleppo, Saladin marched on Harem, a fortress on the outskirts of the Principality of Antioch, held by Surhak, a minor Mamluk. Saladin offered him the city of Bosra and property in Damascus in exchange for the fortress, but Surhak demanded more, and was deposed by his own garrison. He was then arrested by Saladin's deputy, Taqi al-Din, on charges of planning to cede Harim to Bohemond III of Antioch. When Saladin received his surrender, he proceeded to organize the defense of Harim against the Crusaders. He informed his emirs in Yemen and Baalbek that he was going to attack Armenia, but that he had to settle administrative details first. Saladin agreed to a truce with Bohemond in exchange for Muslim hostages and ceded Azaz to Alam ad-Din Suleiman and Aleppo to Saif al-Din al-Yazkuj, respectively an emir of Aleppo who had gone over to his side and a Mamluk from Shirkuh who saved from assassination attempt on Azaz.

Against the Crusaders

On September 29, Saladin crossed the Jordan River to attack Baisan, which he found empty. The next day he looted and burned the city and moved west. He intercepted Crusader reinforcements coming from Kerak and Shaubak on the way to Nablus and took prisoners. Meanwhile, the main crusading force led by Guido de Lusignan left Sepphoris in the direction of Afula. Saladin sent 500 skirmishers to harass them and marched against Ain Jalut. When the Crusader force, the largest produced by the kingdom without outside aid but still inferior to Saladin's army, advanced, the Ayyubids abandoned Ain Jalut. After some Muslim incursions, in Zir'in, Forbelet and Mount Tabor, the crusaders still did not venture to attack the main body of the enemy army, and Saladin withdrew once his troops began to deplete.

Crusader counter-attacks prompted further assaults by Saladin, particularly in the face of harassing Reynald of Chatillon who continued to harass caravans between Syria and Egypt and boast of new attacks on Mecca. Saladin would besiege his Kerak fortress twice (site of Kerak in 1183), Reynaldo's base in Transjordan, to which he would reply by looting pilgrim caravans on the hajj. Finally, the intervention of the pragmatic Count of Tripoli, Raymond led to an agreement with a truce for four years.

After the failure of his sieges in Kerak, Saladin momentarily returned his interest to his Mesopotamian project, resuming his attacks on Mosul. However Masud was now allied with the Persian ruler of Azerbaijan and Jibal, who in 1185 retaliated with counter-attacks across the Zagros Mountains, giving Saladin falter. Mosul's defense, hopeful with the idea of support, became entrenched. Saladin fell ill and in March 1186 agreed to a peace treaty with Mosul, which probably recognized Mosul's autonomy in exchange for recognition of Saladin's conquests and mutual support against the Crusaders. Saladin would move in the following days on the area, taking advantage of the opportunities that arose to take positions against the Persians or the Seljuks of the Sultanate of Rüm such as Khilar and Mayafarekin before resuming their fight with Jerusalem.

The Holy War

The Beginning and the Battle of Hattin

The war that would destroy the overseas Christians was provoked by Reinaldo de Châtillon, a nobleman who has survived to this day with the image of lord of lands on the border and famous for practicing banditry and looting. He had previously violated truces to attack caravans, seized pilgrims heading to Mecca, tried to desecrate Muslim holy places and looted the Christian island of Cyprus, as well as being a frequent protagonist of power intrigues at the Jerusalem court. Modern chroniclers often present him as an extremist who forced the war even though he had no possible way to win it. However, he had been one of the few who had caused Saladin serious trouble: by attacking him on his own land endangering Muslim holy places, he had damaged his image as the Sultan and moral leader of the Muslims, he had withstood Saladin's siege in the fortress of the Knights' Krak and was a veteran of the Battle of Montgisard, the last great Crusader victory in the Holy Land, and of Le Forbelet, a draw against Saladin after the Battle of Afula.

In 1186, in violation of the agreed truce, Reinaldo attacked a large Muslim caravan in which it was even said that Saladin's own sister was traveling, something uncertain. Faced with the foreseeable reprisals of the then main leader of the Muslims, the king consort of Jerusalem Guido de Lusignan carried out levies gathering all the forces of the kingdom, with which he went against Saladin, who had the help of the ambiguity of Raymond III of Tripoli, a member of a court faction opposed to Reinaldo, who initially did not oppose Saladin's march on his lands from the Principality of Galilee, which guaranteed him that his fortresses would not be attacked. However, he ended up joining the royal army that Reynaldo led against Saladin's march into Galilee. The final confrontation took place in 1187, next to some hills called the Horns of Hattin. In the battle the attacks of the light cavalry and the Saracen archers caused the crusader army to delay its idea of reaching Lake Tiberias and had to camp on the plain of Maskana. Finally thirsty and without strength, they were defeated by Saladin.

The victory was total for Saladin: he had destroyed almost all the enemy forces, he had captured the main warlords (King Guido de Lusignan, Reinaldo de Châtillon, the Grand Master of the Knights Templar, Gérard de Ridefort...), had captured or eliminated most of the knights of the religious orders (including Roger de Moulins, Grand Master of the Hospital) and had taken from the Christians the True Cross, their most precious relic.

Only a few barons were able to escape and lead some resistance to Saladin. Count Raymond III of Tripoli, who commanded the vanguard, was able to escape capture when the Muslims opened the siege and surprisingly did not bother him in charging him. He did not turn back to help the rest of the Christian army. Joscelino III of Edessa, Balian of Ibelin and Reinaldo of Sidon, who commanded the rear, were able to break the Muslim defense and escape as well.

The illustrious prisoners were well treated, in fact the anecdote is told of how Saladin offered a glass of snow to the king of Jerusalem, thirsty from the journey in the desert. The only exception was Reinaldo who was executed by Saladin himself, it is said, when he tried to take the cup that he had given Guido de Lusignan as a sign of hospitality, since Saladin had promised to kill him with his own hands for the cruelty he had committed. shown against even defenseless civilians and despite the agreed truce. The custom in the region was to give mercy to the enemy once they had eaten and drunk with him and Saladin did not want the hospitality he offered the king to extend to Reynaldo.

It is not the desire of kings to kill kings, but that man had transgressed all borders, and so I treated him like that.Saladin

The Conquest of Jerusalem

Following his victory at Hattin, Saladin occupied the north of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, conquering Galilee and Samaria without too much difficulty taking advantage of both the lack of a Christian army with almost all Christian military forces eliminated or captured at Hattin and the confusion and lack of an organized command with the king, the main rulers and the masters of the religious orders prisoners. Tiberias, capital of the principality of Raymond's wife of Tripoli, was finally besieged and taken. Saladin marched against the coast, reducing Acre's defense and seizing the prosperous coastal port. Neighbor Arsuf fell along with her. Nazareth, Sepphoris, Caesarea, Haifa were taken one after another. The arrival of the fleet from Egypt, which swept away the Crusader armada, further reduced the chances of a successful Christian defense. Subsequently, he headed for the coast, taking one port after another. Thus fell Sidon, Beirut, Byblos, Thoron, and the lands bordering the County of Tripoli with the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The only exception was Tyre, a place located on an easily defended cape which, commanded by the Marquis Conrad of Montferrat, a nobleman who had come to visit some relatives and who showed great leadership, offered an orderly resistance. Saladin left an army in front of Tire and marched south with the aim of conquering Ascalon, a vital place for the defense of Egypt, despite the fact that his emirs urged him to take Jerusalem. Saladin freed the Grand Master of the Temple, Gérard de Ridefort, in exchange for the Templar strongholds of Gaza, Darum, and their last strongholds in Samaria, and King Guy of Lusignan in exchange for Ascalon, which, however, refused to surrender. Despite everything, it was taken shortly after by Saladin, along with Ramla and Ibelin (in Arabic, Yubna).

Once communications with Egypt were secured, he laid siege to Jerusalem. At that time, Balian of Ibelin, a member of one of the main noble families, asked Saladin to be able to go from Tyre, where he was fighting, to Jerusalem, to get his wife and children out of there in exchange for not collaborating in the defense. from this city. However, he was recognized, and he was asked to command the resistance of the city, so he sent Saladin a message asking him to exempt him from keeping his word not to fight against him, to which Saladin agreed.

Initially, any proposal for capitulation was rejected, since no Christian wanted to cede the city, which they considered holy like the Muslims. Saladin decided, therefore, to take it by force. In October 1187 the situation of the defenders was already desperate, and Balián tried to negotiate the surrender. Saladin refused because he had sworn to take the city by force when his initial offers were rejected and he no longer had a reason to give in to anything (it is said that while Balian was explaining his conditions, a Saracen standard was suddenly raised on a bulwark, showing that the Saladin's troops had already entered). However, when Balian threatened to completely destroy the city rather than surrender it unconditionally, Saladin consulted with his emirs and decided to agree to negotiations that included sparing the lives of all the inhabitants in exchange for surrender, although they demanded that they pay a tax. per head.

Once in possession of the city, he handed over Christian holy sites to Orthodox priests. Although he turned the churches into mosques, he took measures to prevent his soldiers from exalting Christian spirits. Balian and the patriarch Heraclius paid for the purchase of almost ten thousand poor people and many who could not pay the tax to leave Jerusalem were still relatively lucky: Saladin's brother, Saif ed-Din (Al-Adil), paid for a good number of them, as alms to Allah for victory. He was not the only one, being followed by various members of the court. Saladin himself, in an act of generosity, forgave all the elders of the city. On October 2, 1187, he entered the Al-Aqsa Mosque, the third holy place for Muslims after Mecca and Medina.

Back on shore, he faced stubborn resistance from Tyre, which after initial surprise was almost impregnable. He also had the support from overseas of the Italian and Sicilian fleets. Some chronicles, generally contrary to Conrad, state that Saladin took Conrad's father prisoner, William V of Montferrat, who had been captured in Hattin. He offered to release Guillermo in exchange for his surrender, but his elderly father encouraged him to resist. Saladin allegedly exclaimed: "This man is a pagan and very cruel!" and ended up releasing him so that he could return with his son. He had more luck with the capture of Tartus, Giblé and Latakia, ports that fell despite the support of the Kingdom of Sicily. He also took Sahyun, a hospitable fortress on a nearby mountain, and advanced on August 11, taking Sarminiyah after a brief siege and the Orontes bank province. Thus he arrived at the border of the Principality of Antioch, from which he seized Barzouyeh and whose capital he besieged before agreeing to a truce.

Kerak, Safed, Belvoir, Kabouab and Chaubac (Montreal), Transjordan fortresses were subjected to long sieges and after fierce resistance from the military orders that defended them, subdued around 1189. Beaufort also fell, along with Tripoli.

The Third Crusade

The consequences of the fall of Jerusalem were not long in coming: Pope Urban III called for a new crusade, the third, to which the main Christian kings attended. Two Christian expeditions were organized to this call.

The first of these, led by the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick I Barbarossa, crossed the Balkans and Anatolia on foot, where he drowned while crossing a river. Without him, his army dispersed, providentially the greatest threat to Saladin disappearing.

The other, led by Philip Augustus of France, Richard the Lionheart of England, and Duke Leopold of Austria, marched by sea. After disembarking in March 1191, they laid siege to San Juan de Acre, which Saladin tried to rescue. However, he failed to break the siege, and the Christians recovered the city. The Crusaders would soon argue among themselves. The King of France abandoned the crusade after the proud Richard took the best palace and did not treat him as an equal, and the Duke of Austria after seeing his banner offended by Richard, who threw him from a bulwark.

Saladin then undertook intense diplomatic activity to free the captives the Christians had taken. However, when after arduous negotiations an agreement had been reached, Ricardo had them executed due to the continuous postponements of payment by Saladin. In said agreement it was stipulated that Saladino would deliver the Vera Cruz in exchange for the 3000 Muslims that Ricardo kept in a cell as hostages. But he thought it was an unnecessary expense to keep those prisoners. The act was a blow to the prestige of Saladin, who was unable to save those who had resisted in the city.

The English king distinguished himself throughout that year in combat, defeating Saladin in Arsuf and recovering some positions on the coast (such as Jaffa). There were contacts, although it was probably a deception by Ricardo, to arrange the wedding of Saif ed-Din, Saladin's brother, with his sister, who would receive Jerusalem with the obligation to protect pilgrims of all faiths. But they failed when Ricardo's sister refused to marry a Muslim.

They both got sick, and then they also recovered. At last, when the King of England heard news of the turbulent situation in his country, he had no choice but to accept peace and a three-year truce, which, while not restoring Jerusalem to the Christians, assured them of the coast between Tire and Jaffa.

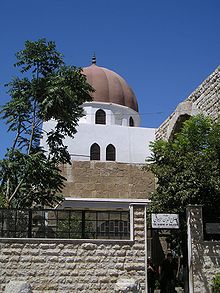

Death and Succession

Saladino died of typhus in 1193 in Damascus and was buried in a mausoleum outside the Umayya Mosque of Damascus. The German emperor Guillermo II donated a sarcophagus in marble, in which he does not rest his body. In its grave the original, wood, in which the body is, and that of marble, empty.

His al-Affal son happened on Syria's throne, thus starting the Ayubí dynasty.

Saladino for posterity

In the West

In Europe, the crusaders who returned to their homes brought with them numerous legends and anecdotes featuring Saladin as the protagonist. With them the figure of Sultan Saladin spread throughout the Christian world. Christian tradition kept Saladin's courtesy, wisdom and chivalry, appearing in numerous stories as a great lord who treated his captives with honor. This is somewhat inaccurate for modern canons, since the members of the military orders that he considered his staunchest enemies were normally forced to choose between forced conversion or death, although, in the morality of the time, their compliance with the rules His social courtesy towards captives and his respect for pacts with the enemy in the face of continual truce violations by the Crusaders in the face of his lack of solid leadership made him strikingly similar to the medieval concept of chivalry.

In several narratives, he appears as an example of the perfect medieval knight, both for his honor and for his wisdom and judgment. In The Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri placed him, along with characters such as Socrates, Aristotle, Homer and Ovid, in Limbo, a space destined for just and illustrious characters, prevented from entering Paradise just for not be baptized. Among the works that mention Saladin in this way, one can name in Spanish El conde Lucanor in its chapters XXV and L, which respectively describe the fictitious captivity of a Christian nobleman in the hands of Saladin, treated with exemplary courtesy, and a Saladin about to fall into temptation but ending up choosing wisely as an example of a good ruler.

But he was also portrayed many times as the "fearsome infidel leader" who had expelled "the true religion" from the Holy Places. In other sources, especially ecclesiastical ones, he is shown as "the Saracen devil", associating him with the devil.

It was the first version that ended up being imposed and so in the XIX century Lessing in his work Nathan the Wise He employs as one of the three leading scholars of the three religions in the book who come to overcome religious differences, choosing him to represent Islam, a tradition that, although previous, has remained. It is common in Western culture to choose Saladin as a representative of the positive values of Islam. The French historian René Grousset would speak of him thus:

It is equally true that his generosity, his piety, his lack of fanaticism, that flower of liberality and courtesy that had been the model of the ancient chronists won him no less popularity in the Crusader Syria than in the lands of Islam.René Grousset (1970)

Currently, not always being historically accurate, there are numerous works (both investigative and fictional) where he is usually shown as a leader of integrity and faithful to his religion, as well as one of the greatest strategists of his This is how it is worth noting the film The Kingdom of Heaven or the second book of the Templar trilogy by Jan Guillou, which use pragmatic and tolerant protagonists who seem closer to Saladin, despite being his enemy, than to the courtiers of Jerusalem, who are often portrayed, with the exception of protagonists often linked to the likes of Raymond III of Tripoli, the "moderate party" at court, as corrupt, fanatical, or merely incompetent.

Fonts

In Spanish

Contenido relacionado

Americo vespucio

August 24

1st century