Russian painting

Russian painting has a history that can be divided into five essential phases.

Since no examples of pictorial tradition have survived among the pre-Christian Slavic peoples, the history of Russian painting begins with the Christianization of the Khaganate of Rus, which occurred around 860, when cultural exchange with the Russian Empire Byzantine brought the tradition of icon painting there. Until the 18th century the predominant genre was religious painting. The westernization of the country by Peter the Great, created, in less than half a century, an entirely new school of painting, of a profane nature, related to the late Baroque that was developing in the rest of Europe. Russian painting was integrated into the general evolution of European art, assimilating new trends. In the mid-19th century a new national school emerged. Russian painting made a significant contribution to Western art during the avant-garde movements of the early XX century, when painters such as Kandinsky o Malevich were the forerunners of abstract painting. About a decade after the 1917 Revolution, the avant-garde was outlawed and painters were forced by the State to follow a populist figurative aesthetic, giving rise to the style known as Socialist Realism, which only lost strength when the political regime began to be liberalized through late XX century. A group of underground artists began to challenge the official art formulas and introduced contemporary concepts into Russian painting, diversifying its horizons and opening local art to the world.

Middle Ages

Frescoes, miniatures and, above all, icons remain from the Middle Ages. There is a strong Byzantine influence in the art of this time. Sometimes it is transmitted directly through artists of Greek origin such as Maximus and, above all, Theophanos or Theophanos the Greek (XIV century), painter of frescoes and icons.

Icons

The tradition of icon painting in Russia was imported from the Byzantine Empire, which provided the newly Christianized state with the necessary materials for liturgy, including religious representations of saints and religious martyrs.

The first national schools arose around the elaboration of icons. The center of culture at that time was Kiev, which today belongs to the Ukraine, and possibly the first active painters in this city were Greeks or Byzantinized Slavs, who served as teachers for the formation of a local school of painting. The first production of what was called the Kiev school closely followed the Byzantine style, but later it began to have its own characteristics, evident in the selection of colors and in the size of the images, as well as in the expressiveness of the figures, so which the Christ Pantocrator, one of the most important formal models of this time, was presented with a more benevolent and human aspect than in the original pattern. A masterpiece of Russian iconography is the Vladimir Virgin, kept in Moscow. It represents the Virgin Mary with the Child Jesus which, although of Byzantine origin (it was given to the Grand Duke Yuri Dolgoruky of Kiev around the year 1131 by the Greek Patriarch Lucas Chrysoberges), later became a model for countless copies and variations. defining one of the most popular typologies of all Russian sacred iconography and being until today one of the most revered images in the entire country. In 1240 kyiv was taken and completely burned down by the Mongols, and the main artistic activity shifted to Novgorod.

The Novgorod school, already active in the XI century, lived its best period between the XII and XIV. Oblivious to the Mongol occupation, it became the main artistic center of the country before being supplanted by Moscow. His first phase preferred icons in frescoes, of which the oldest examples are in the Church of the Savior in Nereditsa and in the Church of St. George in Stáraya Ladoga. The Novgorod school is distinguished by the intensity of the colors, applied without mixing or gradations of tones, minimal shading, energetic and precise drawing, and a preference for clear composition with simple symbology that is easily readable by the people. In the XIII century, the style changed: the colors softened, the composition became more dynamic and spontaneous and the graphic aspect predominated more than the pictorial Unlike Kiev, more Byzantine, the Novgorod school assimilates elements of local folk art, the appearance of its figures is less hieratic and more humanized, similar to Russian people. His fixed and penetrating gaze established direct contact with the viewer, achieving a more dreamy, indirect and introspective expression.

In the XII century other regional schools were also formed in Vladimir, Suzdal, Yaroslavl and Pskov (Mirozhsky Abbey, tied to Byzantine tradition.13th century the Mongol invasion devastated Russia and severed its historical ties with Byzantium, ruining many of its icon-producing centers, except for Novgorod and Pskov, where the icon painting tradition continued to live on. emotional expression of his figures and by the use of differentiated color tones, especially with regard to green, orange and red.

The Moscow school was promoted, along with other local teachers, by Theophan the Greek (c. 1330-h.1410), trained in Constantinople. The origins of this school are obscured by the almost complete non-existence of primitive examples, but it is known that it arose roughly together with Novgorod and that by Theophan's arrival there was already significant artistic activity. He, along with the notable Andrei Rublev, though they possessed very diverse styles, brought this school to its first major flowering in the 15th century, at the time when the influence of Moscow grew, after the expulsion of the Mongols, and it became the center of religious orthodoxy. Rubliov, born around the year 1360 and died in Moscow c. 1430, is an artist about whose life little is known. He trained in Moscow with Projor of Gorodets and Theophanes the Greek. He lived as a monk in the monastery of San Sergio. Of his work, the icon of the Trinity (currently in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow) stands out. Dating around the year 1430, it is considered to be the most important Byzantine icon of the Russian school. It represents the Trinity through the biblical scene called "Mamré's vision": three angels appear to the patriarch Abraham. It is characterized by the melancholic air, of intense spirituality. The angel in the center, in a red robe, is believed to represent Christ with a tree in the background. The one on the left would be God the Father and the one on the right, the Holy Spirit. The perspective is typical of the Byzantine type, that is to say, inverse, the lines opening up as they move away from the viewer's eyes.

It is to these artists of the Moscow school that we owe the definition of the iconostasis: a wall covered with icons that was raised to the point of completely hiding the altar, isolating it from the congregation. It is a significant alteration from the Byzantine altar model, and was introduced in works carried out in the Blagoveshchenski Cathedral in Moscow around 1405.

The expulsion of the Mongols made it possible for the icon tradition to resurface or start in other cities, such as Tver, Suzdal, Rostov or distant Kargopol. Among these minor centers, the Tver school stands out, which distinguished itself by its use of exotic shades of blue and turquoise in a lighter palette.

Icon painting was maintained throughout the Modern Age, taking as an aesthetic reference the characters of classical Byzantine painting, which prevailed over Italian influences. At the beginning of the XVI century, Dionysus or Dionisios (c. 1440-1510) stood out as an iconographer in Moscow. The abbot of Volotsk wrote him a letter defending the icons that became famous: "Letter to an iconographer." Dionysus and his disciples are responsible for the frescoes in the Dormition Cathedral in the Kremlin, as well as portraits of the Tsar.

In the following century, Simon Ushakov (1626-1686) stood out as the first Russian engraver, who worked in Moscow, creating a new style together with Vladimirov, in which tradition is preserved and combined with the novelties of Western painting. Dionisios and Ushakov renewed the concept of pictorial space, paying attention to chromatic subtleties and emphasizing mysticism in their art, to the detriment of the dramatic aspect. The influence of Western painting is noticeable in its use, especially visible in some of the works of Ushakov, in a discreet chiaroscuro to accentuate the illusion of three-dimensionality. Another distinctive element is the appearance of the secular portrait, known as parsuna, also influenced by the West but governed by the conventions of religious painting.

Despite these innovations, icon art declined in the 17th and 18th centuries. They are increasingly realistic and narrative; decorative goldsmithing, a secondary element of the icons, is gaining more and more prominence, occupying a larger pictorial surface. Mystical content is lost in favor of the decorative. The miniature is preferred, a diversification of sacred themes due to the influence of the literary flowering of the country, and the Stroganov school appears in the same city of Moscow.

This school preferred the miniature, for its colors and the great refinement and detail in the images. Among his teachers were Prokopii Chirin, Nikifor and Istoma Savin. The Stroganov school, named after the wealthy Stroganov family who patronized it, was influential until the late 17th century, when the Profane art supported by the state and the nobility became the center of new pictorial trends.

Among the last regional icon schools was that which flourished around the Trinity and Saint Sergius Monastery in Jolui, which began its activities in the 18th century XVII and quickly gained much prestige in the north of the country. In 1882 its production was organized by the Alexander Nevsky Brotherhood. They began a large production of icons and frescoes in the main cities, of the highest quality. When communism took hold in Russia, within the broader framework of religious persecution, the Jolui school was closed. However, its refined technique was not lost and the Jolui school was reopened in 1943, then headed by a graduate at the Leningrad Academy, U. A. Kukuliev. It was transformed into an office of applied arts, focused on the production of lacquered miniatures. The rehabilitation of the Orthodox Church in Russia made possible the revival of icon painting, being practiced in Jolui itself and other centers such as Palej.

The most comprehensive collections of Russian icons are in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the Pushkin Museum in Moscow.

Thumbnails

In the Middle Ages, frescoes and miniatures were painted. In those of a popular nature, such as the Kludov Psalter (Moscow), marginal representations abound; in the aristocratic ones the miniatures occupy the whole page. The tradition of illuminated manuscripts began in kyiv and developed in parallel with icon painting, with which it has stylistic points in common. Despite relying heavily on Byzantine art, Anglo-Norman, Carolingian and Ottonian influences are also present, reaching Russia via medieval trade routes between Russia and the rest of Europe. preserved is the Ostromir Gospels, composed around the year 1056 by the deacon Gregor and his workshop, for the patron Ostromir of Novgorod. In its pages as illustrations, the influence of Byzantine models is clearly perceived, which demonstrates the high level that the local culture had reached by then, just seventy years after the introduction of writing in the region.

Other important medieval works include the Sviatoslav Miscellany, from the 12th century, the Siisky Gospels, from 1339, with various scenes in an elegant style, the Fyodorovsky Gospels, from 1327, or the Kiev Psalter, from 1397, with three hundred and three miniatures dealing with various themes, sacred and profane, animals and plants, and the Nóvgorod Gospel Book, from 1575, with figures of the evangelists and decorated initials.

But there are equally important miniatures on profane texts, such as the great Radzivill Chronicle, the oldest and one of the most precious of its kind, a richly decorated narrative recounting the history of Russia between the 5th and 13th centuries, produced in the XV century. The chronicle Licevoy svod, 1480, with battle scenes.

Unlike what happened in Western Europe, the tradition of illuminated manuscripts continued in Russia during the Modern Age. Thus, it is worth mentioning the manuscript of The legend of the defeat of Mamai, from the XVII century, a historical romance, and the Book of the Tsars' Titles, from 1672, with a series of regal portraits and decorations by Kremlin artists in the XVII. The miniature tradition began to wane at the end of the 17th century with its replacement by printed books, although isolated copies can still be found in the 19th century.

Westernization of Russia

A radical change in Russian art occurred with the accession of Peter the Great. In his project to modernize the country and make it culturally equal to the great European nations, the arts had a special importance as a way of illustrating the advances of civilization. He attracted foreign artists to Russia and sent talented young Russians to study in Italy, France, England and the Netherlands. Foreign artists who traveled to Russia in the 18th century included Jean-Baptiste Perronneau, Jean-Baptiste Le Prince, Stefano Torelli, Heinrich Buchholz, Johann Baptist von Lampi the Elder, Pietro Rotari, Jean-Louis Voille, Louis Caravaque and Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, who after the arrest of the French royal family during the Revolution fled the country with her youngest daughter Julie. In Russia, she found her experience dealing with aristocratic clientele very useful. She was received by the nobility and she painted numerous members of Catherine the Great's family. While there, Vigée-Le Brun was made a member of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts. To Vigée-Le Brun's dismay, Julie married a Russian nobleman.

There was already some timid influence from the West, as can be seen in the parsuna and in sacred authors such as Karp Zolotariov, who mixed the Italian-Dutch baroque school with the Russian-Byzantine tradition in an original way. But the Western impact on Peter's reign was unprecedented; Baroque aesthetics was adopted in painting, now almost all of it dedicated to profane subjects, without any shadow of Byzantine archaism but also with a few features of its own identity. Russian artists trained abroad fully understood the technical and stylistic principles in Western painting.

The first painter to be educated entirely outside of Russia was Andrei Matveyev, who studied in Flanders and the Netherlands for eleven years. When he returned to Russia, he became one of the leading figures in the renewal of Russian painting: Ivan Nikitin studied with Tommaso Redi in Florence, and Alexei Anthropov with Louis Caravaque. Nikitin and Anthropov illustrate the transition between the tradition of the parsuna and typically Western portraiture.

Westernization is accentuated in the later reigns. Catherine II (reigned 1762-1796), who was a Francophile, lover of the arts, and avid collector, stimulated painting by creating the Hermitage Museum and others. It went from Baroque to Rococo, and signs of neoclassical illustration appear. Westernized painting has since been fully integrated into the culture of the elites. In particular, the portrait praises the nobility, which it represents through typical postures and decorations. Among the Russian portrait painters, Fyodor Rokotov (1736-1808), Dmitri Levitski (1735-1822) and Vladimir Borovikovski (1757-1825) stood out; they demonstrated originality in relation to their foreign models and evidenced a very high degree of quality that Russian painting of the Western tradition reaches in a relatively short time. Levitski, specifically, stood out as a portraitist of Catherine II, although he died in poverty. Landscaping also developed, with Fyodor Alekséyev (1754-1824) and Fyodor Matvéyev (1758-1826), pioneering landscape painters in Russia, who had traveled through Italy. And the "great style" of history painting begins to have an influence. Other painters of the same generation were: Alexei Belski, Ivan Argunov, Semyon Shchedrin and Anton Losenko.

In 1757, the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts was created, which Catherine II later called the "Imperial Academy of Arts." This government department supervised the entire artistic system in Russia, organized teaching, distributed prizes and scholarships, hired foreign teachers, created its own collection of foreign works for student illustration, and encouraged Neoclassicism. The historic Academy building on The Neva River in St. Petersburg today houses the Ilya Repin St. Petersburg Academic Institute for Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, but is still informally known as the St. Petersburg Academy of Art.

The new Russian school

After the almost literal importation of foreign aesthetics in the previous century, in the 19th century stylistic and ideological advances led to the establishment of a genuinely Russian school of art. At the beginning of the century the Imperial Academy had its heyday under the leadership of Aleksandr Stroganov. Neoclassicism also entered its most brilliant phase, the strongest influence being that of Ingres, but then it lost its strength and immediately followed one another rapidly, and throughout the entire century, the various trends: Romanticism, Naturalism, Realism. and Symbolism.

Romanticism advocated making the neoclassical canon more flexible. He preferred intimate portraits of psychological characterization, idyllic Mediterranean landscapes that academic artists know when traveling through Italy or dramatic historical scenes. The art, in general, extends to wider circles, far from the court. Silvestre Cedrin (1791-1830) painted views of classical ruins. Karl Briullov (1799-1853), a professor at the Academy, cultivated various genres, but he is known above all for his history painting, his Last Day of Pompeii being well known. Alexander Ivanov is known above all for a religious work to which he devoted twenty years of his life: Appearance of Christ to the People . Other names in the transition from neoclassicism to romanticism are Maksim Vorobiov, Vasily Tropinin, Orest Kiprensky and Alexei Venetsyanov.

The Pugachev Revolt of 1773-74, which unsuccessfully sought to abolish serfdom. On the occasion of the Napoleonic Wars, the middle classes, particularly the army officers, knew better the harsh reality of the people, and witnessed the heroism of the soldiers. These circumstances made the life of the lower classes an acceptable subject for "great art." Of course, in principle it had to be presented in an idealized way, diluting the harsh reality of the serfs and peasants in a gentle bucolicism. For the same reasons, the genre scene that shows domestic scenes of the bourgeois class proliferates. The majestic geography of the country and the human types and typically local customs, caught the attention of the artists, so that the portrait and the landscape were becoming, little by little, more objective and naturalistic. In addition, a new interest arises in the history of Russia, its battles and central figures, the life of the former boyars, mythology and popular religiosity; as a result, paintings are created that visually reconstruct the national life of the past, but in a romantic and medievalist interpretation.

Intellectuals of the time such as Nikolai Dobroliúbov and Nikolai Chernishevsky argued that art should not distance itself from reality, but rather explain and judge it. The painters then considered that art was something more than the affirmation of the supremacy of the ruling class or the entertaining and uncompromising portrait of popular life, and which should be used to educate a broader public morally and socially. Thus arose an art of social, realistic criticism, which painters wanted to be able to cultivate without the direction of the Academy. Thus, in the middle of the century, an artistic nationalism appeared, which represents the first truly original moment of Russian painting since the consolidation of the schools of medieval icons. This painting focused on depicting the Russian people and landscape.

Pavel Fedotov (1815-1852) stands out from this first half of the century, a Muscovite painter who realistically but ironically portrayed the bourgeois society of his time in works such as The Marriage Request and The young widow. A landscape painter halfway between romanticism and realism was Lev Lvovich Kamenev (1831-1886), in whose paintings the study of light on the surface of the water stands out. The new painting was supported by the influential critic Vladimir Stasov.

However, the Imperial Academy remained bound by rigid conventions; he preferred historical and mythological subjects, Italianate landscapes, and conventional portraits of the nobility. It was an art that was beginning to be outdated, although there were talented teachers among its ranks, such as Aleksandr Litóvchenko. Visiting foreign scholars such as Franz Xaver Winterhalter and Carl Timoleon von Neff left some of their best work in Russia, especially in the field of portraiture. The Academy, given its intimate relationship with the constituted power, could not embrace a cause that was essentially populist and bourgeois, although among the new artists there is no decrease in technical quality in relation to the academic ones.

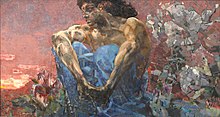

In 1863, thirteen artists, led by Ivan Kramskoi (1837-1887), dissatisfied with the academic line, created the so-called Peredvízhniki (Society of Traveling Exhibitions), which sought to recover a certain Russian pictorial tradition, particularly icon painting, but with a naturalistic treatment. It was enormously successful and reached a much wider audience. In its first twenty-five years of activity, the Street Vendors' Society attracted the attention of leading Russian artists, produced more than three thousand works, and reached an audience of one million. people in about fifteen cities. Not only secular painting was affected by the innovations of the Vendors. Also the sacred art of Mijaíl Vrúbel (1856-1911), Iván Kramskói and Nikolai Gue showed the assimilation of its principles. Vrubel belonged to the Abramtsevo Circle; he was a highly original draftsman, who is part of the transition from realism to symbolism; he dealt with themes inspired by the Russian Orthodox religion, particularly with the figure of the devil. The influence of the Sociedad de los Ambulantes was so great that it forced the Academy itself to review its positions: he accepted the trend, which he called ideological realism, and later hired some of its members as professors. The Society fought for a nationalist art that was also a weapon for denouncing social injustices; It was the vanguard of the avant-garde of the moment until it itself, already conquered the acceptance of its ideals by the Academy, began to become more rigid, proscribing the most radical experimentations of Modernism. Even so, it provided the basis for the later formation of Socialist Realism.

The most prominent of the Streetwalkers was Ilya Repin (1844-1930), who is credited with introducing realism into Russian painting. He trained as an icon painter and then attended the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts. In detailed canvases he described the society of his time, with its inequalities ( The Volga Sergators , Easter Procession in the Kursk Region ), and also episodes of Russian history; he also stood out as a portraitist of composers and writers. Vladimir Makovski (1846-1920) also belonged to this group of Streetwalkers, who began with social scenes and gradually adopted more and more political themes; Fiódor Vasíliev (1850-1873), one of the best Russian realists, who made numerous landscapes; Isaac Levitan (1860-1900), the most outstanding landscape painter of the time, influenced by both Alekséi Savrásov (1830-1897) and Camille Corot and who found great defenders of his art in writers such as Chekhov and Tolstoy; Valentin Serov (1865-1911), a student of Repin and with an academic background, cultivated both landscape and portraiture, and was a stage designer for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Other notable members of the street vendors' society were: Abram Arkhipov, Nikolai Bogdanov-Belsky, Mikhail Clodt, Nikolai Kasatkin, Arkhip Kuindzhi, Rafail Levitsky, Vasily Maksimov, Grigory Miasoyedov, Vasily Perov, Illarión Prianishnikov, Konstantin Savitsky, Ivan Shishkin, Vasili Surikov, Viktor Vasnetsov and Nikolai Yaroshenko.

Avant-garde painting

At the end of the 19th century, there were those who advocated more liberal ideas than the Peredvízhniki (Walkers), more open to the influence of Western art. Among them was the group called World of Art (Mir Iskusstva), founded in 1889 by the painter and set designer Léon Bakst (1866-1924), Sergei Diaghilev and Alexandre Benois. Mir Iskusstva is also the name of the magazine they published. They attacked the obsolescence of Peredvízhniki (Moving Exhibition Society) and the unnatural character of industrial society, and promoted creative individuality and the Art Nouveau spirit under a positivist banner. Wishing to make art accessible to all, they chose cheaper materials such as gouache and watercolor and reduced the scale of their work. Konstantín Korovin, who was also a decorator and set designer, (1861-1939) was part of both the Abramtsevo Circle and the World of Art; he cultivated the genre of landscape and portrait. Repin's student was Boris Kustódiev (1878-1927) who was a member of the World of Art, the Page of Diamonds and, after the Revolution, of the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia. He made satirical illustrations for newspapers such as Ádskaya Pochta . Konstantín Yuón (1875-1958) also belonged to the Mundo del Arte group, who had exhibited with the Peredvízhniki, who had important critical and theoretical work; from 1925 he joined the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia. Kuzmá Petrov-Vodkin (1878-1939) was also a member of the World of Art, with highly original work, a pioneer in avant-garde painting. The World of Art group dissolved and was replaced by the Union of Russian Artists, later reappearing under the old name.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Russian culture was in a state of feverish effervescence. Modern styles such as symbolism or impressionism were adopted, and historical styles were also revisited through neo-primitivism, neo-Gothic or neo-romanticism. Thus, artists such as Konstantín Bogaevsky, Nikolai Krymov, Víktor Borísov-Musátov, Piotr Subbotin-Permiak, Natalia Nesterova, Vasily Denísov, Konstantín Korovin, Mikhail Nesterov and Abram Arkhípov created a bridge between academic figuration and modern visual arts, including important changes. in pictorial technique. Later, cubism, expressionism and futurism penetrated Russia, which were combined with nationalist elements to give rise to a new aesthetic, around 1910, which was called the Russian avant-garde. At this time, it is Russian painting that makes a transcendental contribution to Western art through experiences such as Constructivism, Suprematism or Rayonism, as well as contributing significantly to the birth and theorization of abstract painting with Kandinski.

In Vitebsk (now Belarus) Marc Chagall was born into a Jewish family. He studied in Saint Petersburg and, after the revolution, was an art curator in Vitebsk. He had a very original style that mixed the influence of Judaism and Russian icon painting. He spent most of his life in France, whose nationality he adopted and where he died.

The work of Wassily Kandinsky ((Moscow, 1866-Neuilly, 1944) illustrates the so-called lyrical abstraction. He studied in Munich, and his work was later included in the Der Blaue Reiter movement. When it broke out After World War I he returned to Moscow.In the USSR he organized the Academy of Artistic Sciences.Back in Germany, he taught at the Bauhaus (1922-1932) until the arrival of Nazism led him to live in France, where he lived until his death. Kandinsky's early work was dominated by Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism. But around 1910 his work became increasingly abstract, simply combining shapes and colors, geometrically. Kandinsky is reputed to be the founder of abstract painting, since the first entirely abstract Western paintings are attributed to him.His essays contributed to the theoretical development of abstract painting: Of the spiritual in art (1910), Of the problem of the form and Point and line on the s surface (1926).

Aleksandr Rodchenko (1891–1956), after having painted his three monochromes (Pure Yellow, Pure Blue, Pure Red, 1918) and El Lissitzky, took advantage of his knowledge of form to progress towards a utilitarian conception of art. Rodchenko created the non-objectivist movement (1915), analogous to Suprematism. Lázar Lissitzky, known as El Lissitzky (1890-1941) illustrated books, then, inspired by constructivism and suprematism, he produced avant-garde works such as the Prouns. At the same time, Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953) created with his abstract reliefs one of the first formulations of what would be called constructivism. He started from the cubist forms, to develop an abstract work in three dimensions. Other renowned figures would be Vladimir Mayakovsky, Varvara Stepanova and Liubov Popova.

Aristarc Lentulov (1882-1943) studied with Kandinski, who was part of the Jack of Diamonds group and exhibited with the World of Art. In the thirties, under the artistic theories of Stalinism, he left abstraction and turned to the figurative.

Cubism is represented by Aleksándr Archipenko (kyiv, 1887- New York, 1964), who invented “archipinture”, mobile paintings; since the 1920s he has lived and worked in the United States.

For their part, Mikhail Larionov (Tiraspol, near Odessa, 1881-Fontenay-aux-Roses, 1964) and Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962), sentimental companions who worked together, took their method of transcription to pure abstraction of the luminous phenomenon, which they called rayonism and which began in Russia in 1910. Rayonism started from other previous tendencies, in particular cubism, orphism and futurism.

After having been the main representative of Cubo-Futurism, Kazimir Malevich (Kiev, 1878-Leningrad, 1935) radically broke with all the old conceptions of art when he painted in 1915 Carré noir, which gave rise to supremacy. He went through post-impressionism, neo-primitivism, cubism and then contacted futurism and Der Blaue Reiter . He wrote the Suprematism Manifesto (1915), as well as From Cubism to Suprematism . In the thirties he abandoned abstraction and returned to figurative painting. Suprematist proposals are the most radical of the Russian avant-garde, as they took geometric abstraction to extremes of simplification in radical works such as Black square on white background. Other participants included Aleksandra Ekster, Olga Rozanova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Anna Kagan, Iván Kliun, Liubov Popova, Nikolai Suetin, Ilyá Chashnik, Lázar Khidekel, Nina Genke-Meller, Iván Puni and Ksenia Boguslavskaya.

The general public did not easily receive these works, accustomed as they were to academic art and moderate modernism. These avant-garde movements sought not only a new sensibility but also art with a positive social function, free from the conventions of bourgeois art. For this reason, when the 1917 Revolution broke out, they were supported by both the revolutionary government through Anatoli Lunacharski, who headed the People's Commissariat for Education, and literary movements that wanted to place art at the service of the proletariat, such as the Proletkult. The first decade after the Revolution saw the origin of an extraordinary avant-garde movement in all the arts, artists had wide freedom of action, the debate on the new role of the arts remained hot, and the tonic was experimentalism. But there came a time when official support ceased. The Communist Party, already firmly installed in power, considered it necessary to create new rules for national art. In 1928 all independent cultural institutions were closed, Lunacharsky was dismissed, and work began on a new official program for Russian culture.

Socialist realism

Once the new regime was established, the artistic innovations of the Russian avant-garde were viewed with suspicion, having emerged before the Revolution, and considered possibly decadent and bourgeois art. In addition, many members of the CPSU, like a large part of the population, did not appreciate avant-garde aesthetics, they rejected an abstraction that they did not understand and that did not seem useful as a doctrinal illustration. It is significant that the last avant-garde exhibition was held in Leningrad between November 1932 and May 1933: Malevich presented highly schematized figurative works, faceless people against empty landscapes.

The new policy became official in 1932 when Stalin promulgated the decree On the reconstruction of literary and artistic organizations. His guidelines were even imposed with violence, severely punishing anyone who rebelled.The restrictions caused many intellectuals and artists to emigrate to other countries. After World War II, the art of the West was once again declared harmful and several painters sent into exile in Siberia. Although rigor was relaxed after Stalin's death, even in the 1970s an exhibition could be closed without warning and destroy the exhibited works.

What was intended was to glorify the struggle of the proletariat for progress and the achievement of an ideal socialist society. According to the Statute of the Union of Soviet Writers of 1934, socialist realism was to be a historically reliable artistic representation of reality in its revolutionary development. It should have an educational character of ideological transformation of the workers in the spirit of socialism. Gorki, decreed that the socialist work should have four essential characteristics. I would be:

- Proletariatthat is, relevant and understandable to the worker;

- Typicalshowing scenes of the daily life of the people;

- Realistin the representational, figurative and verifiable sense;

- Partidariasupporting the ideals of the State and the Party.

As the proletarian was the center of this new society, he once again became an object worthy of study, as in the romantic era or that of the Walkers. Also its leader should be praised and represented in an exalted way, along with factory and peasant environments. Now being the State the only patron, every artist became an employee of the state machinery, and painting, associated with the graphic arts, was frequently reproduced on a large scale in propaganda posters.

Socialist realism was figurative and optimistic in nature. As for its historical veracity, it is rather unreal, incurring in excesses when it comes to representing the strength, the virtues or the joy and contentment of the proletariat. Options were limited, and the style soon became repetitive, declining in quality. There was no place for experimental works, which were outlawed as decadent, obscene, vulgar, formalistic, pessimistic or degenerate, and therefore, from the beginning, anti-communist.

There are many criticisms that have been made of socialist realism: the destruction of national culture, imposing an artificial one; the abolition of the organic ties between the creator and the work, replaced by an a priori program; the obligation to deal with certain topics; the isolation of Russian art from contemporary trends in the rest of Europe; the suppression of spontaneity and creative individuality. But, above all, the repression of those who deviated from the norm is condemned: small details could lead an artist to exile or death.

Nevertheless, some of this art reached a high level, both aesthetically and ethically and technically. Many of the painters had been trained at the Academy, and many also adhered to these principles of good will, because they were found in their individual ideals. Among its most typical representatives were Izaak Brodski, Kuzmá Petrov-Vodkin, Georgi Riazski, Borís Ioganson, Aleksándr Gerasimov, Aleksándr Moravov, Iván Vladimirov, Borís Vladimirsky, Karp Trojimenko, Tarás Gaponenko, Aleksándr Laktionov, Piotr Dobrinin, Alekséi Lisenkov, Valentin Lisenkov, Vasily Ivanov, Vladimir Krikhatsky, Mikhail Bozhie, Vasili Saicenko and Nikolai Terpsikhorov.

The renewal of Russian painting

After Stalin's death in 1953, socialist realism began to be attacked by the Communist Party itself in aspects such as the cult of personality. Artists who made a career following his advice, such as Aleksandr Gerasimov, author of idealized portraits of Joseph Stalin, lost their official positions, and others who had been banned, such as Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, were rehabilitated. But this new atmosphere of freedom did not achieve great advances, and socialist realism remained the main guideline in painting.

The dissident artists, who became known as the mavericks, continued to work largely in obscurity and isolation, though at the time they felt united around a common purpose. They were not an organized group, nor did they have a purpose. unified aesthetic. But they had a common goal: to demystify the artificial and authoritarian idealism of state art, which did not reflect reality as it intended. There were maverick groups in Moscow, Saint Petersburg and other cities. In the 1970s the authorities accepted them, albeit in a limited way. There was no market for them, and only a small part of their work managed to be exposed. American collector Norton Dodge, with the help of foreign diplomats and tolerant local authorities, clandestinely acquired a large collection of more than 17,000 works between 1956 and 1986, which he installed in the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University in the United States. Among the non-conformists were Erik Bulátov, Lidia Masterkova, Koriún Nahapetián, Vladimir Nemujin, Aleksándr Rappoport, Yevgeny Rujin, Vasili Sítnikov, Oleg Vasíliev, Vladimir Yankilevski and Anatoli Zvérev. Russian conceptualists, centered in Moscow, who worked on the principles of conceptual art. Among them were the aforementioned Erik Bulátov, Ilyá Kabakov, Komar and Melamid, Andrei Monastyrsky and Víktor Pivovárov.

With the gradual opening up of the Soviet Union's politics in the 1980s, which eventually led to the disintegration of the entire communist bloc, the entire official art program also collapsed. Artists like R. Bichuns, P. Torda, D. Zhilinski, E. Shteinberg, M. Romadin, M. Leis and V. Kalinin were widely recognized. Russia was definitely opened up to the advances of contemporary Western art and there was a rapid expansion in the Russian painting scene, a phenomenon that continues to this day.

Other pictorial traditions

There are other pictorial traditions in Russia, apart from conventional painting, such as lacquered miniatures and primitive or folk painting.

Lacquered miniatures arose in the 18th century around the city of Fedóskino, which is why they are also known as «Fedóskino miniatures». These are paintings, usually on papier-mâché, using not only oil but rich pigments such as mother-of-pearl, precious metal dust, in such a way that it creates the effect of a silver shine. Its peak was the 19th century. The subjects are varied: landscapes, hunting scenes, floral compositions, and portraits, but most of all scenes from Russian legends and local genre scenes were preferred, such as tea drinkers with samovars, troikas, and scenes from Russian peasant life. Other important centers of production besides Fedóskino are Kholui, Zhóstovo, Mstiora and Pálej. Contemporary Fedóskino painting retains the typical features of Russian folk art.

Then there is a popular, primitive, naive and folk painting that began to appear in the early 18th century. The primitive, anonymous artists, who were outside the state schools, repeated previous formal models, using traditional techniques. They had some knowledge of art from often working for the rural nobility, who wanted to imitate the urban nobility by furnishing their mansions with works of art. They developed a portrait derived from the tradition of the parsunas.

These folk artists can be distinguished, though not easily, from the ingenuous or "naïf," who were cultured artists, not of the people, but who created a unique and extravagant style that they then repeated like a formula. The naive appeared at the end of the XIX century and the arrival of communism had a strong impact on them, multiplying this type of work.

All these artists apart from official art, the primitives and the naive, have recently received more attention from the government and collectors, with museums dedicated to the preservation and dissemination of these works.

Contenido relacionado

Lautaro

Aten

Annex: Visigothic kings