Russian literature

The term Russian literature refers not only to the literature of Russia, but also to literature written in Russian by members of other nations that gained independence from the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) or by emigrants who were welcomed in it. With the dissolution of the USSR, various cultures and countries have claimed several ex-Soviet writers who, however, wrote in Russian. Russian literature is characterized by its marked depth with key figures for universal literature such as Dostoevsky or Tolstoy, and it began, like all of them, in the form of oral tradition without written cultivation until the Christianization of Kievan Rus in 989 and, with this, of a proper alphabet to accommodate it.

The creators of this alphabet were the Byzantine missionaries Cyril and Methodius; they took different spellings from the Latin, Greek and Hebrew alphabets, and devised others. At first the Russian written language used two graphic systems—the Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabets; Glagolitic, supposedly also invented by Cyril and Methodius, was abandoned, and Russian literature as we know it today is written and read in the Cyrillic alphabet, in its modality called the Russian alphabet.

Popular oral tradition

The popular oral tradition of the skomorojis (minstrels) and skaziteles, a kind of itinerant bards who came from the Byzantine Empire or the Slavic countries, was expressed through the bylinas (chants or songs) that united popular pagan and ecclesiastical traditions in the form of rhythmic prose accompanied by gusli. The bylinas recount exploits of the Bogatyri who defended Russia against Pecheneg and Cuman nomads and various fantastic monsters. The most famous bylinas heroes are Ilyá Múromets (Ilyá de Múrom), Dobrynia Nikítich and Alyosha Popóvich ("Alyosha son of a cleric (priest)"). In the oral tradition there are also traditional Russian folk songs and tales that began to be collected in writing in the XIX century when Aleksandr Afanasiev compiled in eight volumes.

Old Russian literature

Literature from the period of Kievan Rus (11th to 13th centuries) and the feudal break (13th to 14th centuries)

Old Russian literature consists of a few masterpieces written in Old Church Slavonic, Church Slavonic, and Old East Slavonic.

In the XI century, all the tribes of the Eastern Slavs were part of Kievan Rus. A single language, Old East Slavic, began to form with some territorial dialects. Only in the XIII century, when Kievan Rus broke up, did Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian begin to develop independently. That is why these three nations have a common period in the history of their literatures.

In the Middle Ages in Russia there were no military orders of chivalry or universities until it was created, already in the XVIII century, the one founded by Mikhail Lomonosov, now called Moscow State University. The centers of learning in medieval Russia were monasteries, but despite everything, in ancient Russia there were literate people, as evidenced by the many Novgorod documents preserved on birch bark dating back centuries XI-XII: letters, ballots, notes, IDs, student exercises, etc. The earliest known book in Old Church Slavonic is the manuscript on wax-covered wooden tablets Novgorod Codex (en:Novgorod Codex) or Novgorod Psalter, containing the psalms 75 and 76 (around the year 1010). The Ostromir Gospels was manuscript in Church Slavonic on parchment in 1056 or 1057.

Today, works in Old Church Slavonic, Church Slavonic and Old East Slavonic require translation into the current Russian language due to its evolution and successive reforms of both the Cyrillic alphabet in Russia and the printing fonts, including the reform undertaken by Peter I of Russia in 1708 that introduced the so-called civil font (Гражданский шрифт). A few works of ancient Russian literature still survive, as well as a large number of manuscripts deteriorated by the effects of multiple invasions and wars. These works, of handwritten elaboration, were generally anonymous. There used to be in that old Russian literature the recurring theme of the glorification of beauty and Russian power, the denunciation of the autocracy of the princes of Kievan Rus and the defense of moral principles.

It can be said that there was a system of literary genres divided mainly into two large groups: secular literature and ecclesiastical literature. In them we find the following subgroups:

Secular Literature

- Historical law

- Historical Narration

- An early propaganda literature.

- Oral traditions like bylinasOral epic poems that merge Christian and pagan traditions. The bylinas They relate the feats and feats made by Russian epic heroes, such as Ilyá Múromets, Dobrynia Nikítich and Aliosha Popóvich, defending the Rus of Kiev from the nomads.

Ecclesiastical Literature

- Hagiographic

- Himnographic

- Literature at the service of the Church

It is difficult to classify these works under a single genre -many chronicles are not homogeneous, since they contain parts belonging to all the aforementioned genres- historical narratives, historical legends, excerpts from treatises with propaganda intent and even hagiographic pieces.

The first period of Russian literature, consisting mainly of the work of clergymen from Russian principalities writing in a language called Slavonic or Church Slavonic, and warlike aristocrats writing in Old East Slavonic, which is not should be confused with the eslavón, it is called the "kyiv Period", and it goes until 1240. It is fundamentally about hagiographies and epic poems.

Russian literature of the period is influenced by Byzantine literature. Several important ecclesiastical works are translations: the Ostromir Gospel Book (1056) and the Florilegios (excerpts from Church Fathers, lives of saints, moral precepts) composed in the XI by Prince Sviatoslav II of kyiv, works by Basil the Great, John Malalas, John Chrysostom. Translations of secular texts include the Romance of Alexander, founded on the story of Alexander the Great, and Action of Devgenis (Digenis Acritas) (Devgénievo deyánie), songs of military deeds, Physiologus.

Works

The most important original works of ancient Russian literature are:

- Néstor's Chronicle (Póvest vremennyj let(second half of the century) XI - beginning of the century XII) It is an important chronicle, where the origins of Russia are explored and its history is linked to that of neighbouring countries. The chronicle covers the period from 852 to Vladimir II Monomaco.

- La Loa de San Vladímiro (Address on Law and Grace; Slovo or zakone i blagodati(1037-1050) by Hilarion of Kiev, metropolis of Kiev (about 1050). In this early propaganda work, Hilarion compares the Jewish Law and Christianity (Grace). It points out that the new divine Grace belongs equally to each nation and that Byzantium cannot monopolize it.

- The most famous lay text is Sing of the Igor Bones (ends of the century XII) written in ancient Eastern Slave. The book is based on an unsuccessful attack by Prince Sviatoslávich of Novgorod-Siverski (from the Principality of Cherníhiv who was part of the Kyiv Rus) against the Polovtsians or Cumsians of the Lower Don region in 1185. The author appeals to the warm Russian princes, calling them to unity against the constant threat of the Turkic peoples of the east.

- La Homily of Vladimir II Monomac (Pouchenie Vladímira Monomaja(about 1117). It is a moral testament, in which Vladimir II Monomachus explains the duty of a prince, outlines the moral principles of a Duke and quotes his life as an example.

- The Journey of Higúmeno Daniíl to the Holy Land (Jozhdenie igúmena Daniila v Svyatúyu zemlyu(beginning of the century) XII). The Travel it deals with the itinerary of the Higúmeno Daniíl (in:Daniel the Traveller) from the Rus of Kiev to Palestine, between 1106 and 1108, realistically and collects different religious legends. It is written in ancient Eastern Slave.

From 1240 to 1480 Russian literature slowed its growth because of the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus in 1223, which led to the decline of Kievan Rus along with the rise of new cultural centers such as Novgorod. Military stories are written in rhythmic prose, such as the anonymous Song of the Disaster of the Russian Land (Slovo o pogibeli zemlí Rússkoi) (XIII) (in this lyrical and tragic work the anonymous author laments the fate of Russia, trampled by the Mongols of Batu Khan and appeals to the Russian princes unite and repel the enemy), or the Kulikovo Cycle (Zadónschina, Song from beyond the Don) (late century XIV-century XV): four stories that evoke the great defeat of the Mongols in 1380. The "Cycle" it gives fame to the Battle of Kulikovo and is similar to the Song of the Hosts of Igor.

The most outstanding ecclesiastical works of the period are:

- Kíevo-Pecherski Paterik (the first half of the century)XIII) - lives of first Russian saints of the Pechérskaya Lavra of Kiev, also known as the Monastery of the Caves of Kiev;

- Supplication (Molenie (slovo) Daniíla Zatóchnikaof Daniil Zatóchnik (Daniel the Prisoner) XIII). In this document, Daniel denounces the arrogance of the rich and demands charity for the least favored, in addition to dedicating an hymn to human intelligence;

- The biography of Aleksandr Nevski (Zhitié Aleksandra Névskogo(sixteenth century) XIII) that mixes hagiography and realistic chronicle.

Russia's Muscovite period (15th - 17th centuries)

15th century

From the reign of Ivan III of Russia - who in 1480 put an end to the vassal relationship that the Principality of Moscow had with the Golden Horde, being the first Grand Prince of Moscow to adopt the title of «Sovereign of all Russia» - Moscow becomes the cultural center. The advances of Renaissance secularism in the XV century provoked turbulent religious and political conflicts that generated an extensive polemical literature in prose (works by Nil Sorski - also called Nil del Río Sora - and Iósif Vólotski (Iósif de Volokolamsk) and their respective followers. Iósif Vólotski tries to impose the Church on the State advocating to expand its power and wealth. Nil del Río Sora, on the contrary, he proposes that the church and monks renounce secular wealth and reorganize the lives of clergymen according to Christian ideals of poverty, work and simplicity.

Within secular literature, the Voyage beyond the three seas (Voyage beyond the three seas; Jozhénie za tri mórya) by Afanasi Nikitin. He was a merchant, traveler and writer who, in the 15th century, discovered India to the Russians traveling to it from the Tver city. The trip took place between 1466 and 1472 and is made up of the notes of his impressions and observations that he took during his itinerary.

16th century

The ecclesiastical literature of the XVI century continues the traditional dispute between Nil del Río Sora and Iósif de Volokolamsk; This polemical and propaganda literature is represented by the works of Maximus the Greek (Miguel Trivolis) (1480-1556), a follower of Nil del Río Sora. His main work is An extensive account of the misfortunes that occurred due to the disorder and excesses of the tsars and contemporary authorities ( Slovo, prostranne izlagáyuschee s zhálostiyu nestroéniya i bezchíniya zaréi i vlastéi poslédnego zhitiyá ) (1534-1539). In this work Maximus the Greek denounces the cruelties, indolence and other sins of the Russian rulers, the tsars, calls for a just and wise regime and explains the duty and moral principles that must govern the conduct of the prince who directs the state. For the first time in Russian history, Maximus the Greek writes that the tsar is responsible for the fate of his country and its subjects, so he can be called to chapter.

In 1553-1564 book printing came to Russia. The first Russian printer was Ivan Fyodorov, who carried out his work in Moscow at the invitation of Ivan IV. The first printed Russian book was the Apostle (1564); The appearance of the printing press was a very important event for the development and dissemination of literature and culture in Russia.

Russian ruler Ivan IV was also a notable writer. His most outstanding work is Epistles to Prince Andrei Kurbsky . This character had deserted during the Livonian War to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and accused Ivan IV of being a tyrant in several epistles that he addressed to his ex-sovereign. Ivan IV replied that the real enemies of the state were the boyars, who were trying to divide Russia into small principalities. The controversy lasted for two decades, but Ivan IV also wrote his opinion on the style of the written language in this period and also composed some poems and musical canons on ecclesiastical themes.

The secular or secular literature of the XVI century is represented by the following works:

• The Domostrói (XVI century), attributed to Archpriest Silvestre, Ivan's confessor IV of Russia. Domostroi brings together the various rules that governed the ordinary life of a Russian family of this period. The book deals with the duty of a citizen respecting the tsar and the church. The man should be the head of the family and responsible for the life of all those close to him and for their true Christian education. The Domostrói proclaims that the wife is entirely subordinate to the husband and recommends punishing cases of misconduct with physical or corporal punishment. It is also a domestic encyclopedia that establishes how an exemplary farm should be managed or how to do household chores. In the XIX century the word domostroi came to denote in Russian everything that was backward and outdated in family life.

• Story of a Young Man and a Young Woman (Póvest or Petré and Fevróni) by Ermolái-Erast (mid-century XVI). The History mixes hagiography and the sentimental novel. Some scientists believe that it is the first completely secular novel in Russian literature.

No other lyric is cultivated than that of a sacred theme, and the form used continues to be the rhythmic prose used in military narratives such as the anonymous Story of the Taking of Pskov (Pskóvskoye vziatie) (1510).

17th century

During the XVII century a momentous event for the history and culture of Russia took place: a schism in the Orthodox Church Russian. In 1652 Patriarch Nikon reformed the liturgy and rites of the Russian Orthodox Church to conform to the contemporary Greek Orthodox Church. This reform also meant a greater subordination of the ecclesiastical establishment to the State, which prompted a strong and tenacious resistance from the part of the town that was later called Old Believers, authors of the religious schism. In this period the most important literary work is the autobiography of the Old Believer Avvakum, excommunicated by the Moscow synod and sentenced to die at the stake in Pustozersk. It is known by the title Life of Archpriest Avvakum (1672-1675).

Also noteworthy in this period are the anonymous costumbrista narrations Tale of Pain and Bad Luck (Póvest o gore i zloschasti) (second half of the XVII), Story of Savva Grudtsyn (Póvest o Sávve Grúdtsyne) (1670) and the satirical Relation of the court of Shemyaka (Póvest or Shemiákinom sudé) (XVIIth century).

Russian literature of the period is already under the influence of Western literature. In 1569 Western Russia came under the influence of Poland and the culture of this nation had a certain influence. The death of Ivan IV of Russia began a time of civil wars known as the Troubled Period. Various wars followed one another: that of the Polish-Lithuanian Community against Russia, that of the Dimitríads (1605-1606), that of Ingria and the Smolensk War; Out of all this chaos emerged the de facto Russian Tsar Vladislaus IV Vasa, who ruled from 1610 to 1612.

In Ukraine, the Khmelnytsky Rebellion led to the disintegration of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The uprising freed the Zaporozhian Cossacks from Polish rule who preferred to ally with the Russian Tsarate. Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the hetman of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, agreed with Alexios I of Russia on a protection treaty, the Treaty of Pereyaslav (1654), and since then Ukraine has established closer relations with Russia. Through Ukrainian and Belarusian literature, some works of Western genres and authors reach Russia, such as the comic short stories of Liber facetiarum by the humanist Poggio Bracciolini, biographies of Roman Caesars, chivalrous novels, picaresque novels, Polish adventure novels, miscellanies and poems were retranslated and Russified from the Polish and Belarusian language versions.

The verse appears in the 17th century with Simeon Pólotski (1629-1680) due to the influence of Polish literature. This divides the Russian metric into two arts, one of rhythmic metric prose, popularizing and felt as more national, and another more similar to the Western one and considered more cultured. Outstanding in this period are The Multicolored Garden (Vertograd Mnogotsvetny) (1677-1678) by Simeon Pólotski (1629-1680) and the Epitaph (Epitafion) by Silvestre Medvedev (1641-1691).

Simeon Polotsky was also the founder of the Russian theatre. He wrote and staged the Comedy of the Parable of the Prodigal Son (Komedia pritchi o blúdnom syne) and Of Tsar Nebuchadnezzar ( O Navujodonósore zaré) (1673-1678), in the court theater of Alexios I of Russia, who was a great theater fan.

Russian literature of the 18th century

In the 18th century Russia became westernized and secularized under the iron scepter of Peter I of Russia. It can be said that secular or secular literature truly begins in Russia with this century. Peter I personally revised and reformed the Russian alphabet by eliminating obsolete letters, simplified the orthographic system making reading more accessible, as well as modified the printing font by introducing the so-called civil font (Гражданский shrift).

Pages reviewed by Pedro I, Cyrillic Alphabet, selection of letters for the civil alphabet

As in other Western literatures of this century, the Enlightenment entered Russian culture, which had its classical period in this century. This Classicism had its pillars in the domain of reason and experience, which is why the period is also known as the "Age of Enlightenment" or "Century of Reason".

The first notable writer of the 18th century is Antioch Kantemir (1708-1744), son of Dmitri Kantemir. He was an important satirical poet and his masterpiece is satire in verse In my opinion: on those who blame education ( Na julyáschij uchenie -1729), against those that they wanted to annihilate the cultural legacy of Pedro I and nine other satires.

The main literary controversy of this century occurred between Vasily Trediakovsky and Mikhail Lomonosov over poetry and versification techniques in the Russian language. Vasily Trediakovsky (1703-1769), a poet and translator, published in 1735 his theoretical work entitled The New Concise Method of Composing Russian Verse (Novi i kratki spósob k slozhéniyu stijov rosíyskij). In opposition to the traditional syllabic verse (see en:syllabic verse) used, for example, by Antioj Kantemir, he introduced the bases of the syllabic-accentual verse [1] (see en:accentual-syllabic verse) as well as the feet called trocheus (_U) and iamb (U_).

Mikhail Lomonosov (1711-1765) in his Essay on the Metrics of Russian Versification (Pismó o právilaj rossíyskogo stikhotvórstva) of 1739 introduced three types of rhythms or feet: the dactylic (_UU), the amphibrachic (U_U) and the anapéstic (UU_), as well as the flat and esdrújula rhymes.

The scientist Mikhail Lomonosov considers himself the founder of modern Russian literature by establishing the rules that were to govern the good taste of literary Russian; he distinguishes three styles, the noble, of Slavonic vocabulary for the epic poem, the tragedy, and the ode; the medium for satire and drama and the vulgar (with popular vocabulary) for comedy and song. He wrote sacred odes, panegyrics and an Epistle on the utility of glass (1752).

Russian theater got a big boost too. The most prominent playwrights of the century were Aleksandr Sumarókov (1717-1777), Mikhail Jeráskov (1733-1807), and, above all, Denís Fonvizin.

The most important work of Aleksandr Sumarókov is the tragedy Khorev (1747), although he wrote another eight, 13 comedies, 3 opera libretti and also some verses.

Mikhail Jeráskov's masterpiece is considered to be his epic poem Rossiada (1778), but he also composed 9 tragedies, 2 comedies and 5 dramas for the stage between 1758 and 1807.

Other notable writers of the period include poets Ivan Khemnitser (1745–1784), Vasily Kapnist (1758–1823), Ivan Dmitriev (1760–1837), and playwright Yakov Knyazhnin (1742 (1740?) – 1791).

Denís Fonvizin (1745-1792) is a brilliant playwright who also had important successes and revivals, gaining great popularity at the same time. His best and most celebrated comedies are El Brigadier ( Brigadir ) (1768) and The Minor ( Nédorosl ) (1782). These pieces ridicule vanity, gallomania or thoughtless copying of everything French and the laziness and backwardness of the landowners, as well as their greed, gluttony and brutality; many quotes from his works became proverbial phrases and are used even in the Russian language today.

Tsarina Catherine II of Russia also possessed literary talent and wrote some plays, for example O tempora! (O vremia), The Deceiver (Obmánschik), A Seduced (Obolschonny), Shaman of Siberia (Shaman Sibirski ) and some other parts. She also elaborated with good style some intelligent Memories .

As for the lyrics, Derzhavin and Karamzín stand out.

Gavrila Derzhavin (1743-1816) was influenced by Lomonosov and Sumarókov and was interested in Jeráskov's attempts at renewal; lover of classical forms, his lyrical breath is sincere. His works are remembered Felitsa (1782), God (1784), Let the thunder of victory resound! (Grom pobedy, razdavaysya!, unofficial anthem of the Russian Empire) (1791), The Waterfall (1798) and Life in Zvansk (Zhizn Zvánskaya) (1807). Derzhavin also experimented with different types of rhythms and rhymes, sounds and images.

The Freemason Nikolai Karamzin (1766-1826) reformed the literary language by introducing many Gallicisms and suppressing Slavonic elements, thereby creating a certain distance between educated and popular Russian. He was also an important historian and modernist of Russian poetry. Thanks to Karamzin, the Russian sentimental novel developed from the 18th century. His masterpieces are Poor Liza (Bédnaya Liza, the first sentimental novel in Russian literature) (1792), Letters of a Russian Traveler (Pisma rússkogo puteshéstvennika) (1791-1792) and the History of the Russian State (Istóriya gosudarstva Rossíyskogo) (1816-1825), where for For the first time, an attempt was made to write the history of Russia with the critical rigor and the method of scientific historiography.

One more notable poetic manifestation in Russian literature of the XVIII century is the "revolutionary" by Aleksandr Radishchev (1749-1802) Journey from Saint Petersburg to Moscow (Puteshestvie iz Peterburga v Moskvu) (1790). In that book he sympathized with the peasant serfs, describing their miserable life and denouncing the inhumane treatment with which the authorities and landowners treated them; he used compassion as a means of revolution and social transformation.

In the 18th century appeared the first Russian literary magazines published by Nikolai Novikov.

The Golden Age of Russian Literature (19th century)

The 19th century is traditionally known as the “Golden Age” of Russian literature. Both poetry and prose reached their peak. At the beginning of the century the main current of Russian literature was Romanticism, although later it would be literary realism that would achieve greater importance.

Literary life in the first half of the 19th century was very lively and varied. Russian society at the time was deeply influenced by the Napoleonic Wars and Russia's victory in the first Patriotic War of 1812. The broad layers of the population experienced the rise of patriotism and were interested in the ideas of the French Revolution. Various political and literary magazines appeared at this time: The Messenger of Europe (Karamzin), The Polar Star (Ryleyev), The Contemporary (Pushkin) and, somewhat later, The Moscow Telegraph (Polevoi), The Telescope (Nadezhdin), etc. The spiritual life of the time exerted influence on the main literary currents. Romanticism in Russia developed in two different ways: the supposed progressive romanticism represented by Kondrati Ryleyev, Wilhelm Küchelbecker, Aleksandr Bestuzhev (Marlinsky), Aleksandr Odoyevsky, Denis Davydov (a hero of the Patriotic War of 1812), Nikolai Yazýkov, Dmitri Venevítinov and Yevgeni Baratynski. The main themes of his poetry are some of the key events in Russian history, freedom, patriotism and some Russian folk motifs. The hardest blow to the idealistic aspirations of Progressive Romanticism was dealt by the defeat in the Decembrist rebellion in 1825, as a result of which many participants in the rebellion, such as members of Russia's noble families, poets and public figures, they were executed or deported to Siberia. Passive or traditional romanticism is represented by the works of Vasili Zhukovski. Also, there is a real struggle between Slavophiles and Westernists.

Aleksandr Pushkin towers above all other Russian poets. He possessed a universal genius; he reformed the literary Russian language breaking with the tradition of the XVIII century, wrote accomplished lyric poems, epic poems (Poltava, The Bronze Horseman, Eugene Onegin), powerful dramatic works in verse (Boris Godunov, Little Tragedies), brilliant prose (Tales of the late Ivan Petrovich Belkin, The Queen of Spades, The Captain's Daughter, Dubrovsky), stories in verse (Ruslan and Lyudmila, Tale of Tsar Saltan, Tale of the dead princess and the seven knights). He became the central figure of Russian poetry of the XIX century, eclipsing other poets, talents who in other circumstances could have been the honor of any national literature. Influenced by Pushkin, a series of poets assumed his recently disappeared voice: Anton Délvig, Piotr Pletniov, Piotr Viázemski, Pavel Katenin and some others, the so-called Pushkinian Pleiad.

After Pushkin's tragic death, the torch of Russian poetry passed to Mikhail Lermontov. In his first poems, he imitated Pushkin and Byron, but his poetic style quickly established itself, it is clearly perceived in the change of themes, as, for example, in the poem The candle in which he speaks of a well-being that can only be achieved by fighting. In other poems he vehemently reflects the thoughts and feelings of the young students who rebel and show their indignation at the situation of the serf, the rejection of tsarist despotism and the passionate aspiration for freedom. His most outstanding works are his lyrical verses, Valerik, Borodinó, The Demon, The Novice, the drama The Masquerade Ball, the novel A Hero of Our Time.

Other notable poets of the first half of the XIX century include the fabulist Ivan Krylov, the poet and playwright Aleksandr Griboyedov, the poets Yevgeny Baratynsky, Konstantin Batiushkov, Alexei Koltsov, Ivan Kozlov, Pyotr Yershov.

The prose of the first half of the XIX century is represented by the great novels of Pushkin, Lermontov and by the works of one more genius of Russian literature, Nikolai Gogol. His most notable works are Evening in a Dikanka farmhouse, Tarás Bulba, Dead Souls, the comedy The Inspector and being El capote his most famous story.

The second half of the 19th century saw the emancipation of serfs in 1861, national humiliation in the Crimean War and the triumphant victory in the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–1878 freeing the Slavic peoples of the Balkans from the Turkish yoke. In total, the society was profoundly influenced by the democratic and humane ideas of the century.

The poetry of the second half of the XIX century is mainly philosophical and realistic. The most notable poets of the moment are Nikolai Nekrasov, Fyodor Tiutchev, and Afanasi Fet. Other notable poets are Alexei Konstantinovich Tolstoy (who also wrote prose and theatrical dramas), Apollon Maikov, Ivan Nikitin, and Alexei Plescheyev.

If the first half of the century was the golden age of Russian poetry, the second half of the century was the golden age of Russian prose. The giants of the time are Lev Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Nikolai Leskov, Ivan Turgenev, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, Ivan Goncharov, Dmitri Mamin-Sibiriak, Vladimir Korolenko, Anton Chekhov. Other notable writers include Sergei Aksakov, Alexander Herzen, Nikolai Chernyshevsky, the satirist Kozma Prutkov (a collective pseudonym), Dmitri Pisarev, Alexei Pisemsky, Gleb Uspensky, Konstantin Staniukovich, Vsevolod Garshin, Fyodor Reshetnikov. The most notable playwright was Aleksandr Ostrovski. Social criticism and literature in the XIX century was represented by the works of Visarion Belinsky, Nikolai Dobrolyubov, Aleksandr Herzen and Nikolai Ogarev.

In the last years of the century, Nikolai Garin-Mikhailovsky, Aleksandr Serafimovich, Aleksandr Kuprin, Ivan Bunin, and Leonid Andreyev appeared on the literary scene.

Some writers turned to children's and youth literature (Vladimir Odoyevsky, who was also one of the first Russian science fiction writers, and Antoni Pogorelsky), and others to tales about local life in certain regions (such as Nadezhda Sojanskaya writing about Ukraine).

The Silver Age of Russian literature. At the crossroads of two centuries (XIX and XX). Symbolism, Modernism and Vanguards

The Silver Age began in the last decade of the 19th century and ended in the 1920s. The "Silver Age" it really marks a new course in Russian literature. After the Positivism and Realism bordering on the Naturalism of the revolutionary writers of the eighties, the poets and writers of this denomination lived in the era of Art nouveau or Modernism and Symbolism. But in Russia those European cultural lines were transformed and molded into completely new forms and ideas. The poets and writers of the Silver Age rejected the supposed engagément or social commitment of the artist and proclaimed that the artist had a messianic or Messiah function, he was a titanic figure who had to find the deep roots of the religion and aesthetics: he had been appointed to foresee the New World and the New Man, he was a free demiurge. During the Silver Age Russian culture reached the height of refinement. This time stood out as an unprecedented spiritual Renaissance in Russia.

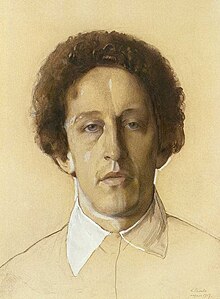

The best-known literary currents of this period are Russian Symbolism - represented by traditional mystical Symbolism and Young Symbolism - that is, works by Innokienty Ánniensky, Vladimir Solovyov (1853–1900), Vasily Rozanov (1856–1919), Dmitri Merezhkovsky (1866–1941) and Zinaida Guippius, Konstantin Balmont (1867–1942), Valery Briusov (1873–1924), Fyodor Sologub (1863–1927), Andrei Bely (1880–1934) and Aleksandr Blok (1880–1921), Vyacheslav Ivanov, and poets similar in spirit to the Symbolists – Maximilian Voloshin, Mikhail Kuzmin; Russian Futurism (David Burliuk, Velimir Jlébnikov, Alekséi Kruchiónyj, first Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vasily Kamensky, Igor Severianin (Igor Lotarev), first Nikolai Aséiev, first Boris Pasternak); Acmeism (first Anna Akhmatova, Nikolai Gumilev, first Ósip Mandelshtam, Sergei Gorodetsky, Gueorgui Ivanov, Irina Odoyevtseva). Poets of the current called "new peasants'" - Sergei Yesenin, Nikolai Kliúiev, Sergei Klychkov (1889-1937), Pyotr Oreshin (1887-1938), Aleksandr Shiriáyevets (1887-1924) - also deserve mention. They combined a wealth of popular and religious images characteristic of the worldview of the Russian peasant with a reckless pursuit of innovation and revolutionary change. There are numerous poets who cannot be attributed to a different literary current, for example, Vladislav Jodasévich, or Marina Tsvetáyeva.

Russian symbolists used the ideas of Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche and Oswald Spengler, expressed interest in mysticism and the occult, in religious disputes and in the popular sects of Russia. The ideas of poets, writers, and philosophers of the time ranged from the acceptance of Nietzsche's Übermensch to the profession of anima mundi, from extreme individualism to 'sobórnost' (collective spirit). What they all shared was an intensive search for new artistic forms and a renewed poetic language. The symbolists put emphasis on the verbal aspect of the archetypal symbols, looking for the new harmony. The Futurists advocated a radical innovation of language, testing the symbolism of sounds and resorting to bold experiments with language. The acmeists advocated the clarity of poetic images, announcing that a balance between meaning and sound had to be achieved. Different artistic groups arose with numerous literary manifestos. The most well-known and scandalous manifesto of the time was the Slap in the Face of Public Taste by the Futurists (1912).

In prose, Russian writers of the period (Andrei Bely, Leonid Andreyev, Fyodor Sologub, Alexei Remizov) used the stream-of-consciousness technique, a logical succession of episodes of disjointed grammar and raw intertwined imagery, mimicking new modes of the organization of texts similar to the rules of cinematographic editing.

Realist writers (Anton Chekhov, Ivan Bunin, Aleksandr Kuprin, Ivan Shmeliov, Boris Zaitsev, Alexei Nikolayevich Tolstoy, Mikhail Osorgin, Maxim Gorky) were also searching for new modes of expression and new literary forms. According to Vikenti Veresayev, a literary theorist of the time, his goal was not the representation of everyday life and customs, but the understanding of the essence of life through the representation of everyday life, to find a new philosophy of life. As a result, prose became more lyrical, and writers employed the synthesis of prose, music, and philosophy (Symbolists), prose, and social action (Futurists).

Traditionally the philosophers of the Silver Age are Nikolai Berdyaev, Sergei Bulgakov, Boris Vysheslavtsev, Semyon Frank, Nikolai Lossky, Fyodor Stepun, Piotr Struve, Ivan Ilyin, Lev Karsavin, Pavel Florensky, Lev Shestov, Sergei Trubetskoi and Yevgeny Trubetskoi, Vladimir Ern, Alexei Losev, Gustav Shpet, Dmitri Merezhkovsky and Vasily Rozanov. Helena Blavatsky's works were read and well known in Russia of the period.

The Silver Age ended with the arrival of the new era – with the formation of the first Soviet state that proclaimed new ideals and was intolerant of all who "would not step in step".

Russian Literature of the Soviet Era

1917-1941

After the October Revolution, Russian literature became somewhat disconnected with the West, for which very little is known, except for a few authors.

After October 1917 most Silver Age writers did not approve of the new Bolshevik regime and left the country, most of them forever. These writers started Russian exile literature.

Those who instead chose to stay in Russia to share the fate of the country and their compatriots reached the height of their creative freedom; but it took a short time for their convictions and hopes for the future of the country to collide with the reality of ordinary life and many were slowly executed or murdered for the terrible lack of almost everything that there was during the Russian Civil War, unable to publish nothing or suffering intimidation to be condemned to total silence. Writers who do not unconditionally support the revolution are eliminated, cornered, emigrated, marginalized or ignored.

At the same time, the first period of the new Soviet era was characterized by the great proliferation of various aesthetic currents, poetic voices and literary experiments. At this time numerous literary groups coexisted that argued, competed and changed their members, generally in a short time. Also within the historical Vanguards, Russian Imaginism arose, founded by Vadim Shershenevich (1893-1942), which claimed the primacy of the image or metaphor over the symbol and a return to traditional poetry; It was cultivated by Borís Pasternak (whose poetry stands out above his prose), Sergei Yesenin, Riúrik Ívnev (1891-1981) and Anatoli Mariengof).

Imagists tried new unexpected metaphors, believing that the surprise of images was the ultimate goal of metaphorical art. The talents of Yesenin and Boris Pasternak reached their peak. The pre-revolutionary poetic current of Acmeism still continued. Anna Akhmatova still wrote poems, although her publications were rare and later ceased. Russian Futurism followed and Cubofuturism (Hylaea or “Guiléia”) (Vladímir Mayakovsky, Velimir Jlébnikov, Borís Pasternak, Víktor Shklovski, Alekséi Kruchiónyj (1886-1968)) flourished for some time. New groups appeared such as OBERIU (Nikolai Zabolotsky, Daniíl Jarms) and the “nichevoki” dadaists. For the first time in human history, writers were able to take part in creating a whole new world, and they jumped at the chance. For example, Velimir Khlebnikov created záum poetry (in Russian: за́умь; en:zaum) or transmental poetry (magic, enchantment in the manner of Asian sorcerers). We must note the titanic figure of the poet and playwright Vladimir Mayakovski, who put his talent at the service of the Revolution. Marina Tsvetaeva largely continued the tradition of Akhmatova, and her poems were the last manifestation of the Silver Age. The poetry of some geniuses like Mayakovsky, Yesenin, Akhmatova, Pasternak, Tsvetayeva exceeds the limits of groups or literary currents.

Outside these groups there were also the famous "Brothers of Serapion” (Vsevolod Ivanov, Mikhail Slonimsky (1897-1972), Mikhail Zoshchenko, Veniamin Kaverin, Konstantin Fedin, Nikolai Tijonov), “Pereval” (headed by literary critic Aleksandr Voronsky and including poet Eduard Bagritsky, writers Mikhail Prishvin and Andrei Platonov and many others), and associations of pro-communist proletarian writers - Proletkult, the Association of Proletarian Writers of Russia or RAPP (for example, Dmitry Furmanov, Aleksandr Fadéyev and many others), LEF (Vladimir Mayakovsky, Ósip Brik, Nikolai Aséev, Alexei Kruchiónyj, for a time Borís Pasternak and some others).

These groups differ from the previous ones in the following:

The “Brothers of Serapion” and “Pereval” advocated for universal human values in art common to all nations, while other groups such as the RAPP and the LEF defended the existence of a social class criterion in literature.

The objective of the LEF (Left Art Front) group and its homonymous magazine, as specified in one of the first issues, was to "revise the ideology and practice of so-called left-wing art, and abandon the individualism to increase the value of art for development communism."

Members of Proletkult and RAPP thought that literature and art had a class character, and, consequently, works of art created by non-proletarian artists should be abandoned and forgotten, because they were foreign to the new society and the "new people".

Constructivism (1923-1930) (Iliá Selvinski (1899-1968); Vladimir Lugovskói (1901-1957)) sang the transition from the capitalist to the socialist state and the triumph of the proletariat and was the first lyrical aesthetic of the proletkult or "proletarian culture"; This intended to create an essentially proletarian art that would exalt collective work; the poets sing to the Revolution, to the machines and to the workers. The members of "Pereval", on the contrary, proclaimed that the main function of art was the knowledge of the world, the main merit of a literary work is not the class content, but the artistic quality; they proclaimed the continuity of art from ancient times to the present age.

Since 1925, two literary camps have faced each other: those grouped in the Association of Proletarian Writers of Russia, known by the abbreviation of RAPP and supported by the State, and those that they call poputchiki or companions of route, writers who attended and accompanied the revolution. The ráppovtsy fight against the group of "Brothers of Serapion", against the constructivists and against the various avant-garde schools, including the LEF group, demanding a less formalist and more vulgar literature. and accessible to the masses in substance and form. Something like the schools of sandalwood and cabbage in the Socialrealism literature of 1955 in Spain.

In 1932, however, all artistic associations were banned, and in 1934 writers were given the "proposition" of joining the Union of Soviet Writers, and bureaucratic administration in the literary world began. In the 1930s, Russia was isolated from the entire world by an iron curtain, and the physical extermination of writers and artists disliked by the regime began, with no further emigration possible.

From that moment on, the so-called socialist realism was established in Russian literature. The main representatives of the current are Maximo Gorky, Mijaíl Shólojov, Alekséi Nikolayevich Tolstoy and Konstantín Fedin. Normativism also appears (social utopia, the social is superior to the personal, an ideal man in ideal circumstances, reality must be disdained and destroyed for a beautiful future, etc.) whose maximum representative was Aleksandr Fadéyev, in addition to modernism or post-realism. (who seeks the meaning of human life in the existential horror of the world, that opposition of man and chaos being tragic, but revealing the essence of man and its price) whose greatest exponents are Yevgueni Zamyatin, Yuri Olesha, Borís Pilniák or Andrei Platonov. They continued the traditions of Silver Age modernism and affirmed man's right to private life. In 1932 the new term "socialist realism" appeared, fusing the ideas of new realism and normativism.

Nevertheless, among the most prominent prose writers of the time (the 20s-30s) the following can be named: the writer and publicist Iliá Erenburg, the prose writer Maximo Gorki, Borís Pilniak, Mark Aguéyev, Mikhail Bulgakov, Olga Forsh, Alexei Nikolayevich Tolstoy, Konstantin Fedin, Andrei Platonov, Boris Lavreniov, Yuri Olesha, Valentin Kataev, Veniamin Kaverin, Pavel Bazhov, Boris Sherguin, Gleb Alekseyev, satirists and humorists Mikhail Zoshchenko, Ilf and Petrov, writers who essentially described the acts of the Red Army in the Russian Civil War Isaak Babel, Dmitri Furmanov, Aleksandr Fadeyev, Nikolai Ostrovsky, Aleksandr Serafimovich, writers of science fiction and social fiction Aleksandr Belyayev, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Vladimir Obruchev, Aleksandr Chayanov, the tragic and romantic Aleksandr grin.

Writers appeared who described the rustic life and nature of Russia, for example Mikhail Prishvin, Yevgeny Charushin. Some writers turned to children's and youth literature – and now the works of Kornei Chukovsky, Arkady Gaidar, Lev Kassil, Andrei Sergeyevich Nekrasov, "The Three Fatties" by Yuri Olesha and "Whiten the lonely candle" by Valentin Kataev, poems by Samuil Marshak, Sergei Mikhalkov are among the most favorite children's books. The historical novel was developed by Vasily Yan, Alexei Nóvikov-Priboi, Sergei Sergeyev-Tsensky, Anatoli Stepanov, Yuri Tynianov, Viacheslav Shishkov, Maria Márich. These writers explored the relationships between the story and the person, analyzing the role of the person in the story. The best known playwrights of the period are Nikolai Pogodin, Vsevolod Vishnevsky.

In the 1930s, the first poems by Aleksandr Tvardovsky and Mikhail Isakovsky appeared.

1941-1953

In 1941 the Great Patriotic War began. New talents appeared, such as Alexei Surkov, Konstantin Simonov, Emmanuíl Kazakévich, Iósif Utkin, Borís Polevoi and Vera Panova, who wrote about the tragedy of war and about the exploits and efforts of Soviet soldiers in their fight to the death against the fascism; Vera Inber and Olga Bergolts, who survived the Siege of Leningrad and described the heroic and tragic 900 days; Pavel Antokolsky, Aleksandr Tvardovsky, Mikhail Isakovsky, Andrei Platonov, Boris Pasternak, Mikhail Sholokhov, Anna Akhmatova, and Ilya Erenburg defended the Soviet Union against the inhumanity of fascism. Many writers perished on the war fronts or died of hunger and cold.

During the time, most of the emigrant writers temporarily embraced the cause of the USSR, given the difficult circumstances the country was going through.

In this period, the common man returned to Russian literature as a literary character: modest heroes and contradictory characters.

The best works of the period are “Vasili Tiorkin”, by Aleksandr Tvardovski; “The Gentle Gift”, by Mijaíl Shólojov; “The Regimental Son”, by Valentin Katáev; “The Young Guard”, by Aleksandr Fadéyev; “Invasion” and “The Golden Car”, by Leonid Leónov; “The Star”, by Emmanuíl Kazakévich; the poem “Pulkovo Meridian”, by Vera Inber; “The Story of a True Man”, by Borís Polevói; the drama “Russian People” and the poetry books “With and without you” and “War”, by Konstantin Simonov; the poem “Son”, by Pável Antokolski, “Zoya”, by Margarita Aliguer; the play "Dragon" by Yevgueni Shvarts; and the historical novel “Young Russia”, by Yuri German.

After the war the authorities exercised harsh repression, and until the death of Stalin the State frequently intervened in literary creation.

The literature of the "thaw" (1953-1968)

The period begins with the death of Joseph Stalin and ends with the end of the Prague Spring. This period is characterized by the gradual renunciation of "socialist realism" as a method of literature, the diverse and saturated literary process, and the return to perpetual human values.

The famous novel “Doctor Zhivago” by Boris Pasternak, whose publication in the USSR was prohibited until 1988, was first published in Milan in 1957 in its Italian-language version. The banned poets of the Russian Silver Age and the 1920s, including Yesenin, Zamyatin, and Nabokov, gradually regained their readership.

In poetry, we can talk about new currents and groups:

- The call poetry of the stadiumswhose representatives are Yevgueni Yevtushenko, Andréi Voznesenski, Robert Rozhdéstvenski and Bela Ajmadúlina. These poets seek the life and poetry they call of consciousness, delicacy, firmness of the soul, energy, and the truth of life. His poetry was social, mainly aimed at the young people of the 1960s who longed for profound changes.

- The "poets with guitar" (such as Bulat Okudzhava or Yuli Kim), who sang the "rope of the cities", proclaimed humanitarianism, delicacy, attention to everyday life with their comedies and private tragedies, and the "bardos with backpacks" (Yuri Kukin, Yevgueni Kliachkin, Aleksandr Gorodnitski, Yuri Víborz

- These currents also advocated for romantic values such as friendship, mutual relief, personal and individual responsibility of every man living for the evil of the world, advocated for the burning character, moral maximalism, renouncing every moral commitment, both in social life and in private.

- Them low poets represented, first of all, by Nikolái Rubtsov with his interest in life in the village, the moral and historical roots of the nation, tradition, nature and popular philosophy.

- La neovanguardia or neofuturism (Vladimir Kazakov, Viktor Sosnora, Guennadi Aiguí among others) and Lianózovo Group (neo-OBERIU) (Oleg Grigóriev, Ígor Jolin, Vsévolod Nekrásov) who traced the paths to conceptualism.

In prose, we can highlight new directions of development:

- Some notable epic novels were written at the end of socialist realism – “The Living and the Dead” (Zhivýe i miórtvye), the trilogy of Konstantin Símonov (during the sixties the first two parts were published), “The Destiny of a Man” (Sudbá cheloveka) of Mikhail Shólokhov, “Life and destiny” (Zhizn and SudbáVasili Grossman.

- A new trend towards the representation of the Great Patriotic War – the so-called "Leric Prose of the Front" or "Prose of Soldiers". The main representatives of this trend are Yuri Bóndarev, Grigori Baklánov, Víktor Astáfiev. They planned the question of the price of a single human life during the war between the piles of victims and losses, addressed human values and studied the entrenchments of a man's moral decay for the inhumane conditions of war.

- Prose of the village - “Brothers and Sisters” (Bratia and siostry) by Fiódor Abrámov, the first collections of stories by Vasili Shukshín and the first novels by Piotr Proskurin.

- Neosentimentalism or classic realism (their highest exponent is Yuri Kazakov) that had as an end the thorough representation of soul movements, intense psychology.

- Movismo (mauvism) by Valentín Katáev.

- Postrealism - “One day in the life of Ivan Denísovich”, “The First Circle”, “The Cancer Pavilion” by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn or the first books by Varlam Shalámov.

- Fantastic reality, whose representatives are Andréi Siniavski (Abram Terts) and Yuli Daniel (Nikolái Arzhak).

We can also mention works by writers belonging to other national cultures, but who also wrote in Russian, such as the great Russian and Kyrgyz writer Chingiz Aitmatov and the Belarusian Vasil Bykau. His works became an organic part of Russian literature.

Russian science fiction reaches a new level in the 1960s with the almost pro-agandist novels of Ivan Yefremov and the early books of Arkady and Boris Strugatsky.

In propaganda literature, the books of Valentin Kataev from the 1960s and “The Brest Fortress” (Bréstskaya krépost) by Sergei Smirnov stand out.

As for children's and youth literature, it is represented by the works of Ágnia Bartó, Vitali Gúbarev, Nikolái Nósov, Lev Davýdychev, Borís Zakhoder, Anatoli Rybakov, Valeri Medvédev or Yevgueni Veltístov.

In dramaturgy, its greatest exponents of the period are Aleksandr Vampilov, Yevgueni Shvarts, Víktor Rózov, Alekséi Arbúzov.

Literature of the 1970s (1968 - mid-1980s)

The period conventionally begins with the end of the Prague Spring and the “tightening of the screws” that followed, and concludes in the mid-1980s with the worsening symptoms of the crisis of the Soviet state and Soviet ideology.

In poetry we can talk about the following new currents and groups:

• Neoacmeism, whose main representatives are Arseni Tarkovski, Semion Lipkin, and Bela Ajmadulina, who continues the complex and refined philosophical tradition of the Silver Age. These authors proclaimed universal personal ties to everything in the world, tested images of culture and its role in the formation and 'maintenance' of a human personality.

•Poets with 'guitars'– Vladimir Vysotsky, Aleksandr Gálich, Yuli Kim. These poets often used the grotesque as a means of criticizing contemporary life, although sometimes their poetry is marked by unprecedented tragic lyricism, as well as psychologism and total identification with the heroes of their verses (soldiers of the Great War Homeland, artists, hooligans (Vysotsky)). These poets were the conscience of the country during the seventies. Galich was forced to emigrate and Vysotsky died prematurely.

• The current of `low poets' was continued, first of all, by Yuri Kuznetsov, who in his work explored the tragedy of the traditional Russian countryside, its life and values, and its gradual destruction. His poetry is marked by a melancholic lyricism and by the search for God in everyday life.

• Neovanguardia – Neofuturism (Vladimir Kazakov, Victor Sosnora, Gennady Aigui) and Lyanozovo Group (neo-OBERIU) (Oleg Grigoriev, Igor Kholin, Vsevolod Nekrasov), who opened a path towards conceptualism, continuing their creative search.

• First verses of Russian rock poets (early 1980s) – 'angry youth', who fought for their right to be different, to have their opinions, their aesthetics and their style that were different from the official point of view.

Mention may also be made of Igor Guberman, a distinguished poet, who also used satire in his poetry. His biting satirical quatrains made him persona non grata in the USSR and he had to emigrate to Israel.

We can also mention the poetic current called neo-romanticism, practiced by singer-songwriters and poets such as Bulat Okudzhava, Yuri Vízbor, Yevgueni Bachurin, Aleksandr Dolski, Yunna Mórits, etc. His poetry was 'low' poetry, intellectual, sometimes sad and ironic, intelligent, very lyrical. For the most part it manifested itself in the form of songs, which are known and valued until now.

Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Andrei Voznesensky continued to write, but their poetry had less resonance than in the 1960s.

In prose, the evolution or gradual disintegration of socialist realism and the return to critical realism should be noted

• Then a new trend in prose appeared, the so-called 'popular epic' (Anatoli Ivanóv with his "Perpetual Call", Piotr Proskurin, Fyódor Abrámov). These works studied the lives of several generations of Russian families, basically peasant families, and their destinies in the Russia "riddled" by the Revolution and martyred in the Great Patriotic War, and in modern everyday life. Those writers examined the moral nerve and spiritual values that enabled people to survive and win in war, but they do not idealize people. These writers were the first to see that the sated life carries its own dangers – 'heart failure', profit-seeking, forgetfulness of eternal values, moral deafness. Related to the current is the 'village prose' whose main representatives are Vasily Belov, Valentin Rasputin, Viktor Astáfiev, Vasili Shukshín, with their heroes intensely searching for 'something else', the meaning of life, the justification of their existence.

• War Prose is represented by the works of Boris Vasiliev, Vitali Zakrutkin, Viktor Astafiev, Yuri Bondarev and Viacheslav Kondratiev. The writers were trying to figure out what kept people human amid the bloody carnage of war, paying homage to the simple people who didn't allow themselves to become inhuman.

• Mention may also be made of the subsequent development of movism (mauvism) represented by the most advanced and mature works of Valentin Katáev. Mauvism is an interesting mix with quasi-documentary parts, visions, reveries with free movement through time in all directions.

It is difficult to label the prose writers of the time as supporters of a specific literary current. However, notable writers such as Vladimir Voinovich, Fazil Iskander and Vasili Aksionov can be highlighted, who preferred the satirical genre for their studies of the absurdity of totalitarian myths, the advanced Yuri Trifonov and Gavriil Troepolski who in his white Bim, black ear revealed and studied moral deafness and the depreciation of values in everyday life, Vladimir Tendriakov and Yuri Dombrovski with their courageous revelation of the injustice of the Soviet regime with almost realistic methods but using parables, the mystical post-realism of Vladimir Orlov and Anatoli Kim. The theme of "Gulag Archipelago" it is studied more deeply by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Varlam Shalamov. The historical prose of the period is represented by the novels of Valentin Píkul, Dmitri Balashov, Alexei Yugov who studied the historical progress of Russia.

A new literary trend in prose appeared, the so-called pedagogical prose. They are novels and short stories that examine the psychology of adolescents, how they grow up, and the problems of their socialization and their personal contact and dealings with adults! These works also raise a question of the responsibility of adults for the fiasco and the lack of spiritual values of adolescents. This current is represented by the works of Albert Lijanov, Simon Solovéichik, Borís Vasíliev, and Vladimir Zheléznikov.

The period can be said to have stimulated Russian literary postmodernism, and the most notable postmodernist writers of the period are Venedikt Yerofeyev, Sasha Sokolov, and Andrei Bitov.

It is the time of the flowering of social and philosophical science fiction, with mature works by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Olga Larionova, Kir Bulychóv, Sever Gansovsky, and the space science fiction of Sergei Snegov. Those works rise above hobby reading, analyzing extemporaneous human nature, raising philosophical questions, and examining different social models.

As for children's and youth literature, it is represented by the works of Vladislav Krapivin, Kir Bulychóv and Eduard Uspenski, the author of Cheburashka.

The best playwrights of the time were Aleksandr Vampilov, Grigori Gorin, Aleksandr Gelman, Edvard Radzinski, Gueorgui Polonski, Aleksandr Volodin and Mikhail Shatrov.

The Russian-language literature of the period created by writers belonging to other national cultures is represented by the mature works of the Kyrgyz Chingiz Aitmatov and Belarusian writers - Vasil Bykau, as well as the new documentary prose of Ales Adamovich and the prose of Confessional War of Many Voices by Svetlana Alexievich, winner of the 2015 Nobel Prize for Literature. Her works not only became a treasure trove of Russian-language literature, but also strongly influenced Russian literature.

Russian literature in emigration

After the October Revolution in 1917 most Silver Age writers did not approve of the new Bolshevik regime and left the country, most of them forever. These writers started Russian exile literature.

We can speak of three periods (or three 'waves' of mass emigration) in the history of Russian literature in exile:

- Literature of the first wave – works by writers and poets displaced by the October Revolution in 1917.

Literature of the “unnoticed generation” - works by their children and writers and poets who matured and began to write in emigration - Literature of the second wave – works by writers and poets displaced by World War II

- Literature of the third wave – works by numerous Soviet dissidents who emigrated to the west in 1970 – mid-1980s

Emigrés of the first wave settled mainly in Berlin, Paris and Prague, making these cities important centers of Russian culture and literature during emigration. Some literary magazines and publishers published the works of Russian émigré writers and this stimulated intellectual discussions as well as cultural life. Writers and poets grouped around the magazines giving rise to literary groups.

The most notable writers of the first 'wave' are Ivan Bunin, Aleksandr Kuprin, Ivan Shmeliov, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Leonid Andreyev, Marina Tsvetayeva and Alexei Nikolayevich Tolstoy (the last two returned to the USSR later). Among other writers and poets who escaped from the Bolshevik regime were Dmitri Merezhkovsky and his wife, the poet Zinaída Guippius, Boris Zaitsev, Mikhail Osorgin, Alexei Remizov, Gueorgui Ivanov, Konstantin Balmont, Teffi (Nadezhda Lojvítskaya), Vladislav Khodasévich, Irina Odóyevtseva, Igor Severianin (Igor Lotariov), Sasha Chorny (Aleksandr Glikberg), Nina Berberova, Arkady Averchenko, Mark Aldanov, Nikolai Otsup, Elizaveta Kuzminá-Karaváyeva (Mother Mary), Vyacheslav Ivanov, Georgy Adamovich, Pyotr Krasnov, and many others. His works explored the apocalyptic motifs, of doom and fate, of the end of civilization, the tragic loneliness of man in a hostile world, proclaimed the price of sustaining a living human soul in a tragic and broken world. Some of the writers analyzed the causes of the revolution and condemned the "brazen, villainous and hooligans" who destroyed tsarist Russia.

The “Unnoticed Generation” were essentially younger writers and poets who matured and started writing as emigrants. The best-known poets of the “unnoticed generation” are Boris Bozhnev, Aleksandr Ginger, Anna Prismanova, Alla Goloviná, Raísa Bloj, Borís Poplavski, Yuri Terapiano, Nikolai Turovérov, Lídiya Chervínskaya, Irina Knorring, Vladimir Smolensky. His lyrical poetry was aimed at the meticulous representation of the movements of the soul, intense psychology and pointed out the motives of a homeless, lonely, embittered man, a soul in pain. The most notable prose writers are Vladimir Nabókov, Gueorgui Yevangulov, Yuri Felzen, Gaito Gazdánov and Leonid Zúrov.

The representatives of the second wave are Ivan Yelagin, Nikolai Narokov, Dmitri Klenovsky, Boris Shiriayev. His works revolved around his bitter experience of life in the USSR.

The third wave of emigration, a 'wave' of dissidents, had its cause in the protest of intellectuals against the omnipresent ideological control and against the “tightening of the screws” after the Prague Spring. Some authors were deported by the Soviet authorities. They settled mainly in New York and Israel. Among the writers of the third 'wave' stand out Joseph Brodsky, Andrei Siniavsky, Dmitri Bobyshev, Sasha Sokolov, Vasili Aksionov, Fridrij Gorenstein, Gueorgui Vladimov, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Sergei Dovlatov, Andrei Amalrik, Lev Kópelev, Irina Ratushinskaya, among others.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union the parapets that divided Russian literature in two were torn down. Today Russian literature is once again united, which means that although Russian literature is diverse, thanks to the great proliferation of various aesthetic currents, poetic voices and literary experiments, points of view and creative approaches, it is no longer tragically divided by an iron curtain and government bans. Authors and their books can easily cross borders.

Literature of the post-Soviet era (mid-80s - present)

In the second half of the 1980s, the crisis of Soviet ideology became very acute and general, which stimulated the appearance of a new, post-Soviet literature. During this time the iron curtain completely disappeared, and the émigré authors returned to Russia. It can be said that the two currents of Russian literature converged, becoming a new current.

As often happens in times of crisis, literature was devoted mainly to revealing and studying the ills and pathologies of Russian society, verging on physiological naturalism, with extreme pessimism, and dividing all manifestations of life into their component parts. Here's why literature from the mid-80s to the beginning of the XXI century earned the nickname 'chernuja and pornuja' in Russia ' – black literature and pornography. A neo-naturalist trend in prose appeared, represented, for example, by Anatoli Azolski and Sergei Kaledin. The texts that condemned the Soviet system and ideology were so numerous that one could speak of a new "official ideology", opposed to the Soviet ideology. But gradually, with the advent of new hope for Russia, the literature became more diverse.

In poetry, the most important currents are:

• Conceptualism (Dmitri Prigov, Lev Rubinstein, Timur Kibirov). The fundamental principle of conceptualism is the 'games' with objects and verbal clichés of socialism and their reduction to absurdity.

• Neo-Baroque, whose best representatives are Yelena Shvarts, Iván Zhdánov and Alekséi Párshchikov.

• A new literary group, “Mitki”, made up of Vladimir Shinkariov, Mikhail Sapego, Olga and Aleksandr Florensky, Dmitri Shaguin, Boris Grebenshchikov, who cultivate a naive sentimentality, simplicity and deliberate foolishness. Most of the leading rock poets and singer-songwriters of the 1990s were more or less associated with the group. The 'Mitkí' they wrote prose and poetry, painted and cultivated a special lifestyle.

• Poets and singer-songwriters of Russian rock: the best known are Aleksandr Bashlachov, Boris Grebenshchikov, Yuri Shevchuk, Viktor Tsoi, Yanka Diaghileva.

• The poems of Karén Dzhanguírov, Dmitri Bykov, Iván Ajmétiev, Bajyt Kenzhéyev, Vladimir Vishnevsky are also of interest.

In recent times the Internet community developed rapidly in Russia, and a new phenomenon appeared, interactive literature (‘Seteratura’) -

Post-modernist prose predominates during the period. The current is mainly represented by the novels of Tatiana Tolstaya, Valeria Nárbikova, Víktor Pelevin, Vyacheslav Pietsuj, Víktor Yeroféyev, Dmitri Lípskerov, Pavel Krusánov, Vladimir Orlov, Nikolai Dezhnev, Anatóli Korolióv, Anatoli Kim, Vladimir Voinóvich, Vasili Aksionov and Dmitri Aksionov.. Boris Akunin's place among post-modernists can be disputed, but at the same time literary critics agree that his prose is of high quality and only masquerades as detective work. Russian post-modernists in their poetics reflect the fin de siècle crisis in literature. The crisis manifested itself in the loss of confidence in many things: culture, language, utopia; at the same time the post-modernists feel a certain nostalgia for the lost faith.

The realistic manner underwent radical changes, as can be seen in the latest novels by Viktor Astáfiev, Anatoli Rybakov (Deti Arbata – The Children of Arbat) and Gueorgui Vladimov.

Post-realism is represented by the works of Ludmila Ulítskaya, Dina Rúbina, Olga Slávnikova, Sergei Dovlatov, Vladimir Makanin, Lyudmila Petrushévskaya, Fridrich Gorenshtein, Alexei Slapovsky, Galina Scherbakova, Efraim Sevela, Aleksandr Kabakov.

The most dubious and scandalous serious writers of the time are Yuz Aleshkovsky, Yuri Mamleyev, Vladimir Sorokin, whose works abound in bodily fluids of all kinds, atrocities and obscene language.

The historical novel is developed mainly by Dmitri Balashov and Boris Vasiliev, who look back at the early days of Russian history, examining the country's rise and fall.

Philosophical and social science fiction flourishes as well, represented by the works of Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Aleksandr Gromov, Oleg Divov, Henry Lion Oldie, Yelena Khaietskaia, Vyacheslav Rybakov, Vladimir Mikhailov, Yevgeny Lukin, Sviatoslav Loginov, Eduard Gevorkyan, Boris Shtern, Sergei Sinyakin, Kholm van Zaichik, Vladimir Khlumov, Dmitri Bykov, Andrei Stoliarov, Aleksandr Yetoev, Leonid Kaganov. It is high-quality literature, which should not be discriminated against on the basis of gender, because it is often difficult to tell where post-modernist or post-realistic games end and where 'mass consumer' literature begins. A very popular science fiction writer is Sergei Lukyanenko, but he gradually becomes commercialized. We can also mention wonderful novels-parables by Ukrainian writers Marina and Sergei Dyachenko, who write in Russian most of the time. The genre of fantastic literature (fantasy) appeared in Russia as well, in the sub-genre called 'Slavic fantasy literature' Maria Semionova is the main author.

As for children's and youth literature, this literature is represented, above all, by the very popular “Pernicious Advice” books by Grigori Oster.

The dramaturgy of time is represented by the post-modernist theater of Venedikt Yeroféiev, Nina Sadur, neo-naturalism of Nikolai Kolyada evolving in the direction of neo-sentimentalism, post-realist plays of Liudmila Petrushévskaya.

List of Featured Writers

|

|

|

List of outstanding poets

|

|

Nobel Prize in Russian Literature

- Ivan Bunin... The Lord of San Francisco (1933)

- Boris Pasternak - Dr. Zhivago (1958)

- Mikhail Shólojov - The gentle gift (1965)

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn - Gulag Archipelago (1970)

- Joseph Brodsky - 1987

- Svetlana Aleksiévich - 2015; Belarusian writer who writes in Russian

Bibliography in Spanish

- Gaev, Arcadio, Soviet literature and its stages. Buenos Aires: Servipres, 1964.

- Ancient Russian Literature. Buenos Aires: Losada, 1972.

- Gatto, Ettore, History of Russian Literature, Barcelona, 1954.

- Gatto, Ettore, Modern Russian Literature. Buenos Aires: Losada, 1972.

- Portnoff, George, Russian literature in Spain. New York: Instituto de las Españas, 1932.

- Schostakovsky, Paul, History of Russian literature from the beginning to the present day. Buenos Aires: Losada, 1945.

- Sanchez Puig, Maria, Dictionary of Russian authors. Ss. XI-XIX, Madrid: Editions del Orto, 1995.

- Russian Theatre. Barcelona: Iberia, 1957. - 2 v.

- Thoorens, Leon, Russia, Eastern and Northern Europe, Madrid: Editorial Daimon, 1969.

- VV. AA., History of Slavic Literatureed. de F. Presa González, Madrid: Cátedra, 1997.

- VV. AA. Medieval Russian literature. Current Outlook. University of Granada, 2007.

- Waegemans, Emmanuel, History of Russian Literature, Madrid: EIUNSA, 2003. ISBN 84-8469-083-0

- Waliszewski, K., History of Russian Literature. Buenos Aires: Argonauta, 1946.

- Soviet Russian poetry (1917-1967). Anthology of poetry, special edition of the magazine Soviet literature (Moscow), 1967, No. 6

Contenido relacionado

Carlos Edmund of Ory

Luis Cernuda

Jarcha