Ruben Dario

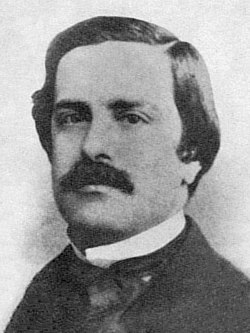

Félix Rubén García Sarmiento, known as Rubén Darío (Metapa, January 18, 1867 - León, February 6, 1916), was a poet, writer, Nicaraguan journalist and diplomat, maximum representative of literary modernism in the Spanish language. He is perhaps the poet who has had the greatest and most lasting influence on the poetry of the XX century in the Hispanic sphere, and for this reason he is called "prince of Castilian letters".

Biography

Beginnings

He was the first child of Manuel García and Rosa Sarmiento, who had married in León in 1866, after obtaining the necessary ecclesiastical dispensations, since they were second cousins.

Manuel's behavior, fond of alcohol and women, made Rosa, pregnant, make the decision to leave the matrimonial home and take refuge in the city of Metapa, where she gave birth to her son, Félix Rubén. The marriage was reconciled; Rosa came to give birth to another daughter of Manuel, Cándida Rosa, who died a few days later. The relationship deteriorated again and Rosa abandoned her husband to go live with her son in the house of her aunt Bernarda Sarmiento, who lived with her husband, Colonel Félix Ramírez Madregil, in the same city of Lion. Rosa Sarmiento met another man shortly after, and established her residence with him in San Marcos de Colón, in Honduras.

Although according to his baptismal certificate Rubén's first surname was García, his father's family had been known for generations by the surname Darío. Rubén explained it in his autobiography:

According to what some elders of that city of my childhood have referred to me, one of my great-grandfathers was named Darius. In the small population everyone knew him by Don Darius; his sons and daughters, by the Daríos, the Daríos. It was thus disappearing the first surname, that my great-grandmother had already signed Rita Darío; and that, as a patronymic, came to acquire legal value; for my father, who was a merchant, made all his business already with the name of Manuel Darío [...].

Dario's childhood was spent in León, raised by his great-uncles Félix and Bernarda, whom he considered his real parents in his childhood (during his early years he signed his school work as Félix Rubén Ramírez). He hardly had any contact with his mother, who lived in Honduras, and with his father, whom he called "Uncle Manuel."

There is little information about his early years, although it is known that on the death of Colonel Félix Ramírez, in 1871, the family suffered financial difficulties, and it was even thought of placing the young Rubén as a tailor's apprentice. According to his biographer Edelberto Torres, he attended several schools in León before going, in 1879 and 1880, to be educated with the Jesuits.

A precocious reader, in his Autobiography he states:

I was a prodigy kid. At three years I knew how to read; as I was told.

Among the first books he mentions having read are Don Quixote, the works of Moratín, The Thousand and One Nights, the Bible, the Oficios by Cicero, and the Corina (Corinne) by Madame de Staël. Soon he also began to write his first verses: a sonnet written by him in 1879, and published for the first time in a newspaper shortly after turning 13: it is the elegy A tear, which appeared in the newspaper El Termómetro, from the city of Rivas, on July 26, 1880. Shortly after, he also collaborated in El Ensayo, a literary magazine in León, and achieved fame as a “child poet”. In these first verses, according to Teodosio Fernández, his predominant influences were the Spanish poets of the time: Zorrilla, Campoamor, Núñez de Arce and Ventura de la Vega.

Later, he became very interested in the work of Victor Hugo, which would have a decisive influence on his poetic work. His works from this period also show the imprint of liberal thought, hostile to the excessive influence of the Catholic Church, such as his composition El Jesuita, from 1881. As for his political attitude, his The most notable influence was the Ecuadorian Juan Montalvo, whom he deliberately imitated in his first journalistic articles. At this time (he was 14 years old) he planned to publish his first book, Poems and articles in prose, which would not see the light until the fiftieth anniversary of his death. He possessed a gifted memory, enjoyed great creativity and retention, and was frequently invited to recite poetry at social gatherings and public events.

In December 1881, he moved to Managua, the country's capital, at the request of some liberal politicians who had conceived the idea that, given his poetic gifts, he should be educated in Europe at the expense of the public treasury. However, the anticlerical tone of his verses did not convince the president of Congress, the conservative Pedro Joaquín Chamorro y Alfaro, and it was decided that he would study in the Nicaraguan city of Granada. Rubén, however, preferred to stay in Managua, where he continued his journalistic activity, collaborating with the newspapers El Ferrocarril and El Porvenir de Nicaragua . In August 1882 he embarked at the port of Corinto for El Salvador.

In El Salvador

In El Salvador, the young Darío was introduced by the poet Joaquín Méndez to the president of the republic, Rafael Zaldívar, who took him under his protection. There he met the Salvadoran poet Francisco Gavidia, a great connoisseur of French poetry. Under his auspices, Darío first attempted to adapt French Alexandrian verse to Castilian metrics.The use of Alexandrian verse would later become a distinctive feature not only of Darío's work, but of all modernist poetry. Although in El Salvador he was quite famous and led an intense social life, he participated in festivities such as the commemoration of Bolívar's centennial, which he opened with the recitation of one of his poems.

Later, he suffered economic hardships and became ill with smallpox, for which reason in October 1883, still convalescing, he returned to his native country.

After his return, he lived briefly in León and then in Granada, but in the end he moved back to Managua, where he found work at the National Library, and resumed his affairs with Rosario Murillo. In May 1884 he was sentenced for vagrancy to eight days of public work, although he managed to avoid serving the sentence. By then he was continuing to experiment with new poetic forms, and even had a book ready for printing, to be titled Epistles and Poems . This second book was never published either: it would have to wait until 1888, when it finally appeared under the title First Notes. He also tried his luck with the theater, and premiered a play, entitled Cada oveja... , which had some success, but has now been lost. However, he found life in Managua unsatisfactory and, advised by the Salvadoran Juan José Cañas, he chose to embark for Chile, where he left on June 5, 1886.

In Chile

He disembarked in Valparaíso on June 24, 1886, according to Dario's own memoirs detailed by his biographer Edelberto Torres Espinosa, or in the first days of June as suggested by Francisco Contreras and Flavio Rivera Montealegre. In Chile, thanks to recommendations obtained in Managua, received the protection of Eduardo Poirier and the poet Eduardo de la Barra. Halfway with Poirier he wrote a sentimental novel, Emelina , with the aim of participating in a literary contest that the novel did not win. Thanks to Poirier's friendship, Darío found work in the newspaper La Época, in Santiago since July 1886.

During his Chilean period, Dario lived in very precarious conditions, and had to endure continuous humiliation by the aristocracy, who despised him for his lack of refinement. However, he came to make some friends, such as the son of the then President of the Republic, the poet Pedro Balmaceda Toro. Thanks to the support of this and another friend, Manuel Rodríguez Mendoza, to whom the book is dedicated, Darío managed to publish his first book of poems, Abrojos, which appeared in March 1887. Between February and September From 1887, Darío resided in Valparaíso, where he participated in various literary contests. Back in the capital, he found work in the newspaper El Heraldo , with which he collaborated between February and April 1888.

In July, thanks to the help of his friends Eduardo Poirier and Eduardo de la Barra, Azul... appeared in Valparaíso, the key book of the recently begun modernist literary revolution. Azul... compiled a series of poems and prose texts that had already appeared in the Chilean press between December 1886 and June 1888. The book was not an immediate success, but it did very well. welcomed by the influential Spanish novelist and literary critic Juan Valera, who published in the Madrid newspaper El Imparcial, in October 1888, two letters addressed to Darío, in which, although he reproached him for his excessive French influences (his "mental Gallicism", according to the expression used by Valera), recognized in him "a prose writer and a talented poet". It was these letters from Valera, later disclosed in the Chilean press and in other countries, that consecrated Darío's fame forever.

Central American journey

This fame allowed him to be a correspondent for the daily La Nación, in Buenos Aires, which at the time was the newspaper with the largest circulation in all of Latin America. Shortly after sending the first chronicle of him to La Nación , he undertook the return trip to Nicaragua. After a brief stopover in Lima, where he met the writer Ricardo Palma, he arrived at the port of Corinto on March 7, 1889. In the city of León he was honored with a triumphant reception. However, he stopped for a short time in Nicaragua, and immediately moved to San Salvador, where he was appointed director of the newspaper La Unión , defender of the Central American union. In San Salvador, he contracted a civil marriage with Rafaela Contreras Cañas, daughter of a famous Honduran orator, Álvaro Contreras, on June 21, 1890. The day after their wedding, there was a coup against the president, General Francisco Menéndez, whose main architect was General Ezeta (who had been a guest at Darío's wedding). Although the new president wanted to offer him positions of responsibility, Darío preferred to leave the country. At the end of June he moved to Guatemala, while the newlywed remained in El Salvador. In Guatemala, President Manuel Lisandro Barillas was beginning preparations for a war against El Salvador, and Darío published an article in the Guatemalan newspaper El Imparcial, entitled “Historia negra”, denouncing Ezeta's treason.

In December 1890 he was entrusted with the direction of a newly created newspaper, El Correo de la Tarde. That year he published in Guatemala the second edition of his successful book of poems Azul..., enlarged, and carrying as a prologue the two letters from Juan Valera that had supposed his literary consecration (since then, it is customary that Valera's letters appear in all editions of this book by Darío). Among the important additions to the second edition of Azul... are the Sonetos aureos (Caupolicán, Venus and Of winter) and The medallions in number of six, to which are added the Èchos, three poems written in French. In January of the following year, his wife, Rafaela Contreras, joined him in Guatemala, and on February 11 they were married in the Guatemalan cathedral. In June, El Correo de la Tarde stopped receiving the government subsidy and had to close. Darío chose to try his luck in Costa Rica, and settled in the country's capital, San José, in August. In Costa Rica, where he was barely able to support his family, burdened by debt despite some occasional jobs, his first child, Rubén Darío Contreras, was born on November 11, 1891.

Travel

The following year, leaving his family in Costa Rica, he went to Guatemala, and then to Nicaragua, in search of better luck. The Nicaraguan government appointed him a member of the delegation that he was going to send to Madrid on the occasion of the four hundredth anniversary of the discovery of America, which for Dario meant fulfilling his dream of traveling to Europe.

En route to Spain, he made a stopover in Havana, where he met the poet Julián del Casal, and other artists, such as Aniceto Valdivia and Raoul Cay. On August 14, 1892, he disembarked in Santander, from where he continued his journey by train to Madrid. Among the personalities he met in the capital of Spain were the poets Gaspar Núñez de Arce, José Zorrilla and Salvador Rueda, the novelists Juan Valera and Emilia Pardo Bazán, the scholar Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo, and various prominent politicians, such as Emilio Castelar and Antonio Cánovas. of the Castle. In November he returned to Nicaragua, where he received a telegram from San Salvador informing him of the illness of his wife, who died on January 23, 1893.

At the beginning of 1893, Rubén remained in Managua, where he renewed his affairs with Rosario Murillo, whose family forced him to marry. In April he traveled to Panama, where he received the news that his friend, Colombian President Miguel Antonio Caro, had granted him the position of honorary consul in Buenos Aires. He left Rosario in Panama, and undertook the trip to the Argentine capital (in a journey that first took him to North America and Europe), he passed through New York, the city where he met the illustrious Cuban poet José Martí, with whom he was linked not few affinities; and then he realized his youthful dream of traveling to Paris, where he was introduced to the bohemian circles by the Guatemalan Enrique Gómez Carrillo and the Spanish Alejandro Sawa. In the French capital he met Jean Moréas and had a disappointing encounter with his admired Paul Verlaine (perhaps the French poet who most influenced his work).

On August 13, 1893, he arrived in Buenos Aires, a city that made a deep impression on him. Behind him was his wife Rosario, pregnant. On December 26, she gave birth to a boy, baptized Darío Dario, of whom his mother would say: " his resemblance to his father was perfect ". However, the child would die of tetanus a month and a half after birth, because his maternal grandmother cut the umbilical cord with scissors that were not disinfected.

In Argentina

In Buenos Aires, Darío was very well received by the intellectual circles. He collaborated with several newspapers: in addition to La Nación , where he was already a correspondent, he published articles in La Prensa , La Tribuna and El Time , to name a few. His work as Colombian consul was honorary, since, as he indicated in his autobiography, "there were almost no Colombians in Buenos Aires and there were no transactions or commercial exchanges between Colombia and the Argentine Republic." In the Argentine capital he led a life of debauchery, always on the edge of his economic possibilities, and his excesses with alcohol caused him to receive medical care on several occasions. Among the characters he dealt with are illustrious politicians such as Bartolomé Mitre, but also poets such as the Mexican Federico Gamboa, the Bolivian Ricardo Jaimes Freyre and the Argentines Rafael Obligado and Leopoldo Lugones.

On May 3, 1895, his mother, Rosa Sarmiento, died, whom he had barely met, but whose death affected him greatly. In October, a new setback arose, as the Colombian government abolished his consulate in Buenos Aires, leaving Darío without an important source of income. To remedy this, he obtained a job as secretary to Carlos Carlés, general director of Posts and Telegraphs.

In 1896, in Buenos Aires, he published two crucial books in his work: Los raros, a collection of articles on the writers who, for one reason or another, most interested him; and, above all, Profane Proses and Other Poems, which marked the definitive consecration of literary modernism in Spanish. As Rubén explains in his autobiography, over time the poems in this book would achieve great popularity in all Spanish-speaking countries. However, in its early days it was not as well received as might have been expected.

Dario's petitions to the Nicaraguan government to grant him a diplomatic position were not heeded; however, the poet saw a chance to travel to Europe when he learned that La Nación needed a correspondent in Spain to report on the situation in the country after the Disaster of 1898. Due to the military intervention of the United States in Cuba, Darío coined, two years before José Enrique Rodó, the metaphorical opposition between Ariel (personification of Latin America) and Calibán (the monster as a metaphor for the United States). On December 3, 1898 Darío He embarked for Europe, and on December 22 he arrived in Barcelona.

Between France and Spain

Dario arrived in Spain with the commitment, which he fulfilled impeccably, to send four monthly articles to La Nación about the state of the Spanish nation after its defeat by the United States in the Spanish-American War, and the loss of its colonial possessions of Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and the island of Guam. These chronicles would end up being compiled in a book, which appeared in 1901, entitled Contemporary Spain. Chronicles and literary portraits. In them, Rubén expresses his deep sympathy for Spain, and his confidence in the recovery of the nation, despite the state of despondency in which he found it.

In Spain, Darío aroused the admiration of a group of young poets who defended Modernism (a movement that was not at all accepted by established authors, especially those belonging to the Royal Spanish Academy). Among these young modernists were some authors who would later shine with their own light in the history of Spanish literature, such as Juan Ramón Jiménez, Ramón María del Valle-Inclán and Jacinto Benavente, and others who are much more forgotten today, such as Francisco Villaespesa, Mariano Miguel de Val, director of the magazine Ateneo, and Emilio Carrere.

In 1899, Darío, who was still married to Rosario Murillo, met, in the gardens of the Casa de Campo in Madrid, the gardener's daughter, Francisca Sánchez del Pozo, an illiterate peasant from Navalsauz (province of Ávila)., which would become the companion of his last years. He took her to France and taught her to read and write, they married civilly and bore her three children, only one of whom would survive him; It was the great love of his life and the poet dedicated his poem "To Francisca" to her:

A stranger to the dolo and to feel an artery, / filled with the illusion of faith, / God's lazarillo on my path, / Francisca Sánchez, accompany me...

In April 1900, Darío visited France for the second time, commissioned by La Nación to cover the Universal Exposition that took place that year in the French capital. His chronicles on this subject would be collected in the book Pilgrimages . At that time he met Amado Nervo in the City of Light, who would be his close friend.

In the early years of the XX century, Dario established his place of residence in the capital of France, and reached a certain stability, not exempt from misfortunes. In 1901 she published in Paris the second edition of Profane Prose . That same year Francisca gave birth to a daughter of the poet, Carmen Darío Sánchez, and, after her delivery, she traveled to Paris to join him, leaving the girl in the care of her grandparents. The girl would die of smallpox shortly after her, without her father getting to know her.

In 1902, Darío met a young Spanish poet, Antonio Machado, a declared admirer of his work in the French capital. In March 1903 he was appointed consul of Nicaragua, which allowed him to live with greater financial relief. The following month his second son with Francisca was born, Rubén Darío Sánchez, nicknamed "Phocás the peasant" by his father. During those years, Darío traveled through Europe, visiting, among other countries, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Germany and Italy.

In 1905 he went to Spain as a member of a commission appointed by the Nicaraguan government whose purpose was to resolve a territorial dispute with Honduras. That year he published in Madrid the third of the capital books of his poetic work: Songs of life and hope, the swans and other poems , edited by Juan Ramón Jiménez. Some of his most memorable poems also date from 1905, such as "Salutation of the Optimist" and "To Roosevelt", in which he praises the Hispanic character in the face of the threat of US imperialism. In particular, the second, addressed to the then President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt:

You are the United States, / you are the invasive future / of the naive America that has indigenous blood, / that still prays to Jesus Christ and still speaks in Spanish.

That same year, 1905, the son with Francisca Sánchez, "Phocás the peasant", died of bronchopneumonia.

In 1906 he participated, as secretary of the Nicaraguan delegation, in the Third Pan-American Conference that took place in Rio de Janeiro. For this reason he wrote his poem "Eagle Salutation", which offers a vision of the United States very different from that of his previous poems:

Well come, magical eagle of huge and strong wings / to spread over the South your great continental shadow, / to bring in your claws, rings of bright reds, / a palm of glory, of the color of immense hope, / and in your peak the olive of a vast and fruitful peace.

This poem was widely criticized by some authors who did not understand Rubén's sudden change of heart regarding the influence of the United States in Latin America. In Rio de Janeiro, the poet carried out a dark romance with an aristocrat, perhaps the daughter of the Russian ambassador in Brazil. It seems that at that time he conceived the idea of divorcing Rosario Murillo, from whom he had been separated for years. Returning to Europe, he made a brief stopover in Buenos Aires. In Paris he met Francisca Sánchez, and together they went to spend the winter of 1907 in Majorca, an island where he frequented the company of the later futurist poet Gabriel Alomar and the painter Santiago Rusiñol. He started a novel, La isla de oro , which he did not finish, although some of his chapters appeared serially in La Nación . Around that time, Francisca gave birth to a girl who died at birth.

His peace of mind was interrupted by the arrival in Paris of his wife, Rosario Murillo, who refused to accept the divorce unless she was guaranteed financial compensation that the poet judged disproportionate. In March 1907, when he was leaving for Paris, Darío, whose alcoholism was already very advanced, fell very ill. When he recovered, he returned to Paris, but could not reach an agreement with his wife, so he decided to return to Nicaragua to present his case in court. At the end of the year the fourth son of the poet and Francisca was born, Rubén Darío Sánchez, nicknamed "Güicho" by his father and the couple's only surviving child.

Ambassador in Madrid

After two brief stops in New York and Panama, the poet arrived in Nicaragua, where he was given a triumphant reception and showered with honors, although he was unsuccessful in his divorce petition. In addition, he was not paid the fees that were due to him for his position as consul, so he found himself unable to return to Paris. After months of negotiations, he got another appointment, this time as resident minister in Madrid for the Nicaraguan government of José Santos Zelaya. He had problems, however, to meet the expenses of his legation due to the reduced budget, and he experienced financial difficulties during his years as ambassador, which he was only able to partially solve thanks to the salary he received from La Nación and in part thanks to the help of his friend and director of the magazine Ateneo, Mariano Miguel de Val, who offered himself as free secretary of the Nicaraguan legation when the economic situation was unsustainable and in whose house, at 27 Serrano Street, he installed his headquarters. When Zelaya was overthrown, Darío had to resign his diplomatic post, which he did on February 25, 1909. He remained faithful to Zelaya, whom he had praised excessively in his book Journey to Nicaragua and Tropical Intermezzo, and with whom he collaborated in the writing of the book The United States and the Nicaraguan Revolution, in which he accused the United States and the Guatemalan dictator, Manuel Estrada Cabrera, of having plotted the overthrow of his government.

During the performance of his diplomatic post, he fell out with his old friend Alejandro Sawa, who had asked him for financial help without his requests being heard by Darío. The correspondence between the two suggests that Sawa was the true author of some of the articles that Darío had published in La Nación.

Last years

After leaving his post at the head of the Nicaraguan diplomatic legation, Darío moved back to Paris, where he dedicated himself to preparing new books, such as Canto a la Argentina, commissioned by La Nation. At that time, his alcoholism caused him frequent health problems and psychological crises, characterized by moments of mystical exaltation and by an obsessive fixation with the idea of death.

In 1910, he traveled to Mexico as a member of a Nicaraguan delegation to commemorate the centennial of the country's independence. However, the Nicaraguan government changed while he was away, and Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz refused to receive the writer. Despite this, Dario was triumphantly received by the Mexican people, who demonstrated in favor of the poet and against his government.In his autobiography, Dario links these protests to the Mexican Revolution, then about to to occur:

For the first time, after thirty-three years of absolute dominion, the house of the old Cesareo that had prevailed was stoned. And there it was seen, you can say, the first lightning of the revolution to bring destruction.

Rebuffed by the Mexican government, Dario sailed for Havana, where, under the influence of alcohol, he attempted suicide. In November 1910 he returned to Paris, where he continued to be a correspondent for the newspaper La Nación and performed a job for the Mexican Ministry of Public Instruction that perhaps had been offered to him as compensation for the humiliation suffered.

In 1912, he accepted an offer from Uruguayan businessmen Rubén and Alfredo Guido to direct the magazines Mundial and Elegancias. To promote these publications, he went on a tour of Latin America, visiting, among other cities, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Montevideo and Buenos Aires. It was also around this time that the poet wrote his autobiography, which was published in the magazine Caras y Caretas under the title The life of Rubén Darío written by himself ; and the work History of my books, very interesting for learning about his literary evolution.

After the end of this tour, and after breaking his contract with the Guido brothers, he returned to Paris, and, in 1913, traveled to Majorca invited by Joan Sureda, and stayed at the Valldemosa charterhouse, in the where Chopin and George Sand had resided three quarters of a century ago. It was on this island that Rubén began the novel El oro de Mallorca, which is, in reality, a fictionalized autobiography. However, the deterioration of his mental health was accentuated, due to his alcoholism. In December he returned to Barcelona, where he stayed at the home of General Zelaya, who had been his protector while he was president of Nicaragua. In January 1914 he returned to Paris, where he had a long lawsuit with the Guido brothers, who still owed him a large sum of his fees. In May he settled in Barcelona, where he printed his last important poetic work, Canto a la Argentina y otros poemas, which includes the laudatory poem for the southern country that he had written years before at the request of The Nation. His health was already very deteriorated: he suffered from hallucinations and was obsessed with death.

At the outbreak of World War I, he left for America, with the idea of defending pacifism for the American nations. Gone was Francisca with her two surviving children, whom the poet's abandonment would throw into misery shortly after. In January 1915 he read his poem "Pax" at Columbia University in New York. He continued on to Guatemala, where he was protected by his old enemy, the dictator Manuel Estrada Cabrera, and finally, at the end of the year, returned to his homeland in Nicaragua.

Death

Rubén Darío arrived in the city of his childhood, León, on January 7, 1916 and died on February 6 after a tragic agony, victim of atrophic cirrhosis caused by alcoholism, which also severely affected his system nervous. Francisco Tovar Blanco, quoting Edelberto Torres, wrote:

Rubén does not hide from his shadow: "The things that happen to me are natural consequences of alcohol and its abuses: also of the pleasures without measure. I've been tormented, a bitter hour. I have known all the alcohols: from the Indians and the Europeans to the Americans, and the rough and rough of Nicaragua, all pain, all poison, all death. My fantasy, sometimes in crisis; I suffer the epilepsy that produces that poison I am saturated with. I feel then aggressive, ferocious, instinct to destroy, to kill. This is how I explain the great murders committed by liquor."

The funeral ceremonies lasted several days, presided over by the Bishop of León Simeón Pereira y Castellón and President Adolfo Díaz Recinos. He was buried in the Cathedral of León on February 13 of the same year, at the foot of the statue of Saint Paul near the presbytery, under a concrete, sand and lime lion made by the Granada sculptor Jorge Navas Cordonero; said lion resembles the Lion of Lucerne, Switzerland, made by the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844).

Dario's archive was donated by Francisca Sánchez to the Spanish government in 1956 and is now in the Library of the Complutense University of Madrid. Francisca had four children with Darío - three died when they were very young, the other in maturity, buried in Mexico. With Darío dead, Francisca married José Villacastín, a cultured man, who spent his entire fortune collecting Rubén's work that was scattered all over the world and which he delivered for publication to the publisher Aguilar, of whom he was a good friend.

Dario's poetry

Influences

The influence of French poetry was decisive for Darío's poetic formation. First of all, the romantics, and especially Victor Hugo. Later on, and decisively, came the influence of the Parnassians: Théophile Gautier, Leconte de Lisle, Catulle Mendès and José María de Heredia. And, finally, what ends up defining Dario's aesthetics is his admiration for the symbolists, and among them, above any other author, Paul Verlaine. Recapitulating his poetic career in the opening poem of Cantos de vida y esperanza (1905), Darío himself summarizes his main influences by stating that it was "strong with Hugo and ambiguous with Verlaine".

In the «Liminary Words» of Prosas profanas (1896) he had already written a paragraph that reveals the importance of French culture in the development of his literary work:

The Spanish grandfather of white beard points to a series of illustrious portraits: “This one — he tells me — is the great gift Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, genius and manco; this is Lope de Vega, this Garcilaso, this Quintana”. I ask him for the noble Gracián, for Teresa la Santa, for the brave Góngora and the strongest of all, Don Francisco de Quevedo and Villegas. Then I exclaimed: “Shakespeare! Dante! Hugo...!” (And inside me: Verlaine...!)”.

Then, when I say goodbye, "Grandpa, I must tell you, my wife is from my land; my dear, from Paris."

The volume Los raros, published the same year as Prosas profanas, is dedicated to brief glosses on some writers and intellectuals. for whom he felt a deep admiration. Among those selected are Edgar Allan Poe, Villiers de l'Isle Adam, Léon Bloy, Paul Verlaine, Lautréamont, Eugénio de Castro and José Martí (the latter is the only author mentioned who wrote his work in Spanish). The predominance of French culture is more than evident. Darío wrote: «Modernism is nothing other than Castilian verse and prose passed through the fine sieve of good French verse and good prose».

This does not mean, however, that literature in Spanish has not been important in his work. Leaving aside his initial period, before Azul..., in which his poetry is largely indebted to the great names of Spanish poetry of the century XIX, like Núñez de Arce and Campoamor, Darío was a great admirer of Bécquer. Spanish themes are very present in his production from Prosas profanas (1896) and, especially, from his second trip to Spain, in 1899. Aware of the decline of the Spanish both in politics As in art (a concern that he shared with the so-called Spanish generation of '98), he is frequently inspired by characters and elements from the past. This is the case, for example, in his «Litanía de nuestro señor Don Quixote», a poem included in Cantos de vida y esperanza (1905), in which the idealism of Don Quixote is exalted.

As for the authors of other languages, mention should be made of his deep admiration for three American authors: Emerson, Poe and Whitman.

Evolution

Dario's poetic evolution is marked by the publication of books in which critics have recognized his fundamental works: Azul... (1888), Profane prose and other poems (1896) and Songs of life and hope (1905).

Before Azul... Dario wrote three books and a large number of individual poems, which constitute what has been called his «literary prehistory». The books are Epístolas y poemas (written in 1885, but not published until 1888, with the title First notes), Rhymes (1887) and Thistles (1887). In the first of these works, the imprint of his readings of Spanish classics is evident, as well as the imprint of Victor Hugo. The metric is classic (tenths, romances, stays, chained triplets, in verses where heptasyllables, eight syllables and hendecasyllables predominated) and with a predominantly romantic tone. The epistles, of neoclassical influence, were addressed to authors such as Ricardo Contreras, Juan Montalvo, Emilio Ferrari and Victor Hugo.

In Abrojos, published in Chile, the most pronounced influence is that of the Spanish Ramón de Campoamor. As for Rimas, also published in Chile and in the same year, it was written for a composition contest in imitation of Bécquer's Rhymes, so it is not surprising that its intimate tone is very similar to that of the Sevillian poet's compositions. It consists of only fourteen poems, with a loving tone, whose expressive procedures (stanzas of broken foot, anaphoras, antithesis, etc.) are characteristically Becquerian.

Azul... (1888), considered the inaugural book of Spanish-American Modernism, includes both prose stories and poems, whose metrical variety caught the attention of critics. It already presents some characteristic concerns of Darío, such as the expression of his dissatisfaction with bourgeois society (see, for example, the story "The bourgeois king"). In 1890 a second edition of the book saw the light, augmented with new texts, including a series of sonnets in Alexandrian.

The period of fullness of Modernism and of Dario's poetic work is marked by the book Prosas profanas y otros poemas, a collection of poems in which the presence of the erotic is more important, and of which concern for esoteric themes is not absent (as in the long poem "Colloquium of the centaurs"). In this book there is already all the exotic imagery typical of Darian poetics: France of the XVIII century, Italy and Spain medieval, Greek mythology, etc.

In 1905, Darío published Cantos de vida y esperanza, which announces a more intimate and reflective line within his production, without renouncing the themes that became hallmarks of Modernism. At the same time, civic poetry appears in his work, with poems such as "To Roosevelt", a line that will be accentuated in El canto errante (1907) and in Canto a la Argentina y otros poems (1914). The intimate bias of his work is accentuated, on the other hand, in Autumn Poem and Other Poems (1910), which shows a surprising formal simplicity in his work.

Not all of Darío's poems were collected in books during the poet's lifetime. Many, appearing in periodicals, were collected after his death. An example, representative of his stage of literary maturity, is the poetry entitled Los motivos del lobo, published in Mundial Magazine in 1913, three years before Darío's death. Inspired by chapter XXI of the Florecillas de San Francisco, which narrates the conversion of the wolf of Gubbio by Francisco de Asís, the Darian version changes the outcome of the story, to print an absolute lyrical character to the final chords of the poem, causing the wolf to return to the mountain because of the wickedness of men.

Formal Resources

Metric

Dario endorsed the motto of his admired Paul Verlaine: «De la musique avant toute chose». For him, as for all modernists, poetry was, above all, music. Hence, he attached enormous importance to rhythm. His work was a true revolution in Castilian metrics. Along with the traditional meters based on the octosyllable and the hendecasyllable, Darío used profusely verses barely used before, or already in disuse, such as the eneasyllable, the dodecasyllable and the alexandrine, enriching poetry in Spanish with new rhythmic possibilities.

Although there are previous examples of the use of Alexandrian verse in Castilian poetry from the XIX century, Darío's discovery consisted of to free this verse from the rigid correspondence that existed until then between the syntactic structure of the verse and its metric division into two hemistiches, resorting to various types of overlapping. In Darío's poems, the caesura between the two hemistiches is sometimes found between an article and a noun, between the latter and the adjective that accompanies it, or even within the same word. Darío adapted this verse to stanzas and strophic poems for which the use of the hendecasyllable was traditional, such as the quatrain, the sextet and the sonnet.

Dario is undoubtedly the greatest and best exponent of the adaptation of the rhythms of classical (Greco-Roman) literature to Hispanic lyric. These rhythms are based on the contrast of stressed and unstressed vowels, and therefore on the syllabic quantity. In Latin, the tonic is not marked as in Spanish with a stronger voice hit, but with a lengthening of the vowel. Rubén would cultivate traditional rhythms (iambic and trochaic as binary, and dactylic, amphibrachic, and anapestic as ternary), and he would also forge his own quaternary rhythms and innovate by combining binary and ternary rhythms in the same verse.

Example of dactylic ternary:

Yinclitas razas ubérrimas, St.gre de HispaNia faithcunda...

Example of amphibrachic ternary:

That's it.cubicchaviNo Ro♪do...

Example of trochaic binary:

Rósa róHa! Plio afoul...

Lexicon

Dario stands out for the renewal of poetic language, visible in the vocabulary used in his poems. Much of Darío's poetic vocabulary is aimed at creating exotic effects. Semantic fields that connote refinement stand out, such as that of flowers ("jasmine", "nelumbos", "dahlias", "chrysanthemums", "lotuses", "magnolias", etc.), that of precious stones ("agate", «ruby», «topaz», «emerald», «diamond», «gem»), that of luxury materials («silk», «porcelain», «marble», «ermine», «alabaster»), that of exotic animals ("swan", "papemores", "bulbules"), or that of music ("lyre", "cello", "clave", "arpeggio", etc.).

Cultisms from Latin or Greek («canéfora», «liroforo», «hipsípila») are frequently found in his work, and even neologisms created by the author himself («canallocracia», «pythagorize»). He frequently uses characters and elements from Greek and Latin mythology (Aphrodite or Venus, often designated by their epithets "Anadiomena" or "Cypris", Pan, Orpheus, Apollo, Pegasus, etc.), and names of exotic places (Hyrcania, Hormuz, etc.).

Figures of Rhetoric

One of the key rhetorical figures in Darío's work is synesthesia, through which it is possible to associate sensations of different senses: especially sight (painting) and hearing (music).

In relation to painting, there is a great interest in color in Darío's poetry: the chromatic effect is achieved not only through adjectives, often unusual (for the color white, for example, adjectives such as « albo", "ebúrneo", "candido", "lilial" and even "eucarístico"), but through the comparison with objects of this color. In the poem "Blason," for example, the whiteness of the swan is successively compared to that of linen, the white rose, the lamb, and the stoat. One of the best examples of Dario's interest in achieving chromatic effects is his «Sinfonía en Gris Mayor» included in Prosas profanas:

The sea as a vast, whipped glass

reflects the foil of a zinc sky;

distant flocks of birds stain

the sharp background of pale grey...

The musical is present, apart from in the rhythm of the poem and in the lexicon, in numerous images:

The harmonic keyboard of his fine laughter...

the lyric crystals

of your laugh...

Metaphor is as important as synesthesia in Darío's poetry.

Symbols

The most characteristic symbol of Darío's poetry is the swan, identified with Modernism to the point that when the Mexican poet Enrique González Martínez wanted to repeal this aesthetic, he did so with a poem in which he urged "to twist the neck to the swan". vida y esperanza, one of whose sections is also entitled "Los cisnes". Salinas explains the erotic connotation of the swan, in relation to the myth, to which Darío refers on several occasions, of Jupiter and Leda. However, it is an ambivalent symbol, which sometimes functions as an emblem of beauty and other times. symbolizes the poet himself.

The swan is not the only symbol that appears in Darío's poetry. The centaur, in poems such as the «Colloquium of the Centaurs», in Profane Prose, expresses the soul-body duality through his half-human, half-animal nature. Spatial images also have great symbolic content in his poetry, such as parks and gardens, an image of the poet's inner life, and the tower, a symbol of his isolation in a hostile world. Many other symbols have been studied in his poetry, such as the color blue, the butterfly or the peacock.

Themes

Erotism

Eroticism is one of the central themes of Darío's poetry. For Pedro Salinas, it is the essential theme of his poetic work, to which all the others are subordinated. It is a sensory eroticism, whose purpose is pleasure.

Dario differs from other love poets in the fact that his poetry lacks the literary character of the ideal beloved (as can be, for example, Laura de Petrarca). There is not one ideal beloved, but many fleeting beloveds. As he wrote:

- Plural has been the celestial / history of my heart...

Erotism becomes the center of Dario's poetic worldview. Salinas speaks of his "panerotic vision of the world," and believes that his entire poetic world is structured in accordance with this main theme. In the work of the Nicaraguan poet, eroticism does not end with sexual desire (although he wrote several poems, such as "Mía", with explicit references to the sexual act), but rather becomes what Ricardo Gullón defined as "longing for love". transcendence in ecstasy". For this reason, sometimes the erotic is closely related to the religious in Dario's work, as in the poem "Ite, missa est" (the words with which the mass concludes according to the Roman liturgy before of the Second Vatican Council, current «You can go in peace»), where he says of his beloved that «her spirit is the host of my loving mass». For Dario, erotic attraction embodies the essential mystery of the universe, as revealed in the poem "Colloquio de los centauros":

- The riddle is the fatal face of Deyanira! / My back still keeps the sweet perfume of the beautiful; / even my pupils call its star clarity. O scent of your sex! O roses and alabasters! / Oh envy of the flowers and jealousy of the stars!

In another poem, from Songs of Life and Hope, he expressed it in another way:

- Flesh, blue woman's flesh! Clay / - said Hugo-, ambrose rather, oh wonder!, / life is endured, / so hurtful and so short, / only for that: / Red, bite or kiss / in that divine bread / for which our blood is our wine! / In it is the lira, / in it is the rose, / in it is the harmonious science, / in it all breathes / the vital perfume of.

Exoticism

Very related to the theme of eroticism is the use of exotic settings, far away in space and time. The search for exoticism has been interpreted by modernist poets as an attitude of rejection of the pacata reality in which they had had to live. Darío's poetry (except for the civic poems, such as the Canto a la Argentina , or the Ode to Miter ), excludes the current events of the countries in which he lived, and focuses on remote settings.

Among these scenarios is the one provided by the mythology of ancient Greece. Darío's poems are populated with satyrs, nymphs, centaurs and other mythological creatures. The image that Darío has of ancient Greece is passed through the sieve of eighteenth-century France. In "Digression" he wrote:

I love more than the France of the Greeks

the Greece of France, because in France

the echo of laughter and games,

His sweetest liquor Venus escancia.

The gallant France of the 18th century is another of the favorite exotic settings of the poet, a great admirer of the painter Antoine Watteau. In «Divagación», which Dario himself referred to, in Historia de mis libros, as «a course in erotic geography», in addition to those mentioned, the following exotic environments appear: Germany of the Romanticism, Spain, China, Japan, India and Biblical Israel.

The presence in his poetry of an idealized image of pre-Columbian civilizations deserves special mention, since, as he exposed in the «Palabras Liminares» to Prosas profanas:

If there is poetry in our America she is in old things, in Palenke and Utatlán, in the legendary Indian, and in the sensual and fine inca, and in the great Moctezuma of the golden chair. The rest is yours, Democrat Walt Whitman.

Occultism

Despite his attachment to the sensory, Darío's poetry runs through a powerful current of existential reflection on the meaning of life. His poem «Lo fatal», from Cantos de vida y esperanza , is well known, where he affirms that:

there is no pain bigger than the pain of being alive

no greater weight than conscious life

Dario's religiosity departs from Catholic orthodoxy to seek refuge in the syncretic religiosity typical of the end of the century, in which oriental influences are mixed, a certain resurgence of paganism and, above all, various occult currents. One of them is Pythagoreanism, with which several of Darío's poems that have to do with the transcendent are related. In the last years of his life, Darío also showed great interest in other esoteric currents, such as theosophy. As many authors remember, however, the influence of esoteric thought in poetry is a common phenomenon since Romanticism. It manifests itself, for example, in the vision of the poet as a magician or priest endowed with the ability to discern true reality, an idea that is already present in the work of Victor Hugo, and of which there are abundant examples in the poetry of Darío, who in one of his poems calls poets "towers of God."

Civic and social issues

Dario also had a facet, much less known, as a social and civic poet. Sometimes commissioned, and others by his own desire, he composed poems to exalt heroes and national events, as well as to criticize and denounce social and political ills.

One of his most outstanding poems along these lines is «Canto a la Argentina», included in Canto a la Argentina y otros poemas, and written on behalf of the Buenos Aires newspaper La Nación on the occasion of the first centenary of the independence of the southern country. This extensive poem (with more than 1,000 verses, it is the longest of those written by the author), highlights the character of the South American country as a land of welcome for immigrants from all over the world, and praises, as symbols of its prosperity, the Pampa, to Buenos Aires and the Río de la Plata. In a similar vein is his poem, "Oda a Mitre", dedicated to the Argentine hero Bartolomé Mitre.

His «To Roosevelt», included in Cantos de vida y esperanza, already mentioned, expresses confidence in the resistance capacity of Latino culture against Anglo-Saxon imperialism, whose visible head is the then President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt. In "Los cisnes", belonging to the same book, the poet expresses his concern for the future of Hispanic culture in the face of the overwhelming dominance of the United States:

- Will we be delivered to the fierce barbarians? / Will so many millions of men speak English? / Are there no more nobles or brave knights? / Will we stop now to cry afterwards?

A similar concern is present in his famous poem "Salutation of the Optimist." Darío's turn was highly criticized when, on the occasion of the Third Inter-American Conference, he wrote, in 1906, his "Salutation to the Eagle", in which he emphasized the beneficial influence of the United States on the Latin American republics.

As far as Europe is concerned, the poem «To France» (from the book El canto errante) is notable. This time the threat comes from bellicose Germany (a real danger, as the events of World War I would show):

- The barbarians, France! The barbarians, the Lutecia face! / Under a broken aura rests your great paladin. / From the cyclop to the coup, what can the laughter of Greece? / What can thank you, if Herakles shakes his cry?

Dario's prose

It is often forgotten that much of Darío's literary output was written in prose. It is a heterogeneous set of writings, most of which were published in newspapers, although some of them were collected in books.

Novel and autobiographical prose

Dario's first attempt to write a novel took place shortly after disembarking in Chile. Together with Eduardo Poirier, he wrote in ten days, in 1887, a romantic serial entitled Emelina , for its presentation at the Varela Contest, although the work did not win the prize. Later on, he tried his luck again with the novel genre with The Golden Man , written around 1897, and set in ancient Rome.

Already in the final stage of his life, he tried to write a novel, of a markedly autobiographical nature, which he did not finish either. It appeared serially in 1914 in La Nación, and bears the title The gold of Mallorca. The protagonist, Benjamín Itaspes, is a transcript of the author, and in the novel there are recognizable characters and real situations from the poet's stay in Mallorca.

Between September 21 and November 30, 1912, he published in Caras y caretas a series of autobiographical articles, later collected in a book as The life of Rubén Darío written by himself (1915). Also of interest for the knowledge of his work is the History of my books , published posthumously, about his three most important books (Azul..., Profane Prose and Songs of Life and Hope).

Stories

Dario's interest in short stories is quite early. His first stories, "On the banks of the Rhine" and "The Colonel's Meatballs", date from 1885-1886. The stories collected in Azul... are especially noteworthy, such as "The King bourgeois”, “The deaf satyr” or “The death of the Empress of China”. He would continue cultivating the genre during his Argentine years, with titles such as "Las lágrimas del centauro", "La nightmare de Honorio", "La leyenda de San Martín" or "Thanatophobia".

Newspaper Articles

Journalism was Dario's main source of livelihood. He worked for several newspapers and magazines, in which he wrote a very high number of articles, some of which were later compiled into books, following chronological or thematic criteria.

Chronicles

Most noteworthy are Contemporary Spain (1901), which includes his impressions of Spain immediately after the disaster of 1898, and the chronicles of trips to France and Italy collected in Pilgrimages (1901). In The trip to Nicaragua and tropical Intermezzo he collects the impressions that his brief return to Nicaragua produced in 1907.

Literary criticism

The collection of portraits Los raros (1896), a kind of vademecum for those interested in new poetry, is of great importance in his overall production. His criticisms of other authors are collected in Opinions (1906), Letters (1911) and Todo al vuelo (1912).

Dario and modernism

Dario is cited as the initiator and maximum representative of Hispanic modernism. While this is broadly true, it is a statement that must be qualified. Other Spanish-American authors, such as José Santos Chocano, José Martí, Salvador Díaz Mirón, Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera or José Asunción Silva, to name a few, had begun to explore this new aesthetic even before Darío wrote the work that has been considered the turning point. departure from Modernism, his book Azul... (1888).

Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that Darío is the most influential modernist poet, and the one who achieved the greatest success, both in life and after his death. His teaching was recognized by numerous poets in Spain and America, and his influence has never ceased to be felt in poetry in the Spanish language. In addition, he was the main architect of many emblematic stylistic discoveries of the movement, such as the adaptation to the Spanish metric of the French Alexandrian.

In addition, he was the first poet to articulate the innovations of Modernism in a coherent poetics. Voluntarily or not, especially from Profane Prose , he became the visible head of the new literary movement. Although in the «Palabras liminales» of Prosas profanas he had written that he did not want with his poetry to «set the course of others», in the «Preface» of Songs of life and hope referred to the "liberty movement that I had to initiate in America", which clearly indicates that he considered himself the initiator of Modernism. His influence on his contemporaries was immense: from Mexico, where Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera founded the Revista Azul, whose title was already a tribute to Darío, to Spain, where he was the main inspiration for the modernist group from which they would emerge. authors as relevant as Antonio and Manuel Machado, Ramón del Valle-Inclán and Juan Ramón Jiménez, passing through Cuba, Chile, Peru and Argentina (to name just a few countries in which modernist poetry achieved special roots), there is hardly a single poet of Spanish language in the years 1890-1910 capable of eluding its influence. The evolution of his work also marks the guidelines of the modernist movement: if in 1896 Profane Prose signifies the triumph of aestheticism, Songs of Life and Hope (1905) already heralds intimacy of the final phase of modernism, which some critics have called postmodernism.

Rubén Darío and the generation of 98

Since his second visit to Spain, Darío became the teacher and inspirer of a group of young Spanish modernists, including Juan Ramón Jiménez, Ramón Pérez de Ayala, Francisco Villaespesa, Ramón del Valle-Inclán, and the brothers Antonio and Manuel Machado, collaborators of the magazine Helios, directed by Juan Ramón Jiménez.

In several texts, both in prose and in verse, Darío showed the respect he deserved for the poetry of Antonio Machado, whom he met in Paris in 1902. One of the earliest is a chronicle entitled «New Spanish poets», which was collected in the book Opinions (1906), where he wrote the following:

Antonio Machado is perhaps the most intense of all. The music of his verse goes in his thought. He has written little and meditated a lot. His life is that of a stoic philosopher. He can say his teachings in deep sentences. He enters into the existence of things, in nature.

Dario's great friend was Valle-Inclán, since the two met in 1899. Valle-Inclán was a devoted admirer of the Nicaraguan poet throughout his life, and he even made him appear as a character in his play Luces de bohemia, together with Max Estrella and the Marquis de Bradomín. Well-known is the poem that Dario dedicated to the author of Tirano Banderas, which begins like this:

This great don Ramon of the chivo beards,

whose smile is the flower of his figure,

Looks like an old tall god.

that is animated in the coldness of his sculpture.

Less enthusiasm for Darío's work was expressed by other members of the generation of '98, such as Unamuno and Baroja. About his relationship with the latter, a curious anecdote is told, according to which Darío would have said of Baroja: «He is a writer with a lot of flair, Baroja: you can tell that he has been a baker», and the latter would have counterattacked with the phrase: « Darío is also a writer with a lot of pen: you can tell that he is an Indian».

Legacy

Dario's influence was immense on the poets of the turn of the century, both in Spain and in America. Many of his followers, however, soon changed course: this is the case of Leopoldo Lugones, Julio Herrera y Reissig, Juan Ramón Jiménez or Antonio Machado.

Dario became a very popular poet, whose works were memorized in schools in Spanish-speaking countries and imitated by hundreds of young poets. This was detrimental to the reception of his work. After the First World War, with the birth of the literary avant-gardes, the poets turned their backs on the modernist aesthetic, which they considered old-fashioned and rhetoricist.

The poets of the XX century showed divergent attitudes towards Darío's work. Among his main detractors is Luis Cernuda, who reproached the Nicaraguan for his superficial Frenchism, his triviality, and his "escapist" attitude. On the other hand, he was admired by poets as far removed from his style as Federico García Lorca and Pablo Neruda, although the former he referred to "his charming bad taste, and the shameless rubble that fills the crowd of his verses with humanity." The Spanish Pedro Salinas dedicated the essay The poetry of Rubén Darío to him in 1948.

The poet Octavio Paz, in texts dedicated to Darío and Modernism, underlined the foundational and disruptive character of modernist aesthetics, for him inscribed in the same tradition of modernity as Romanticism and Surrealism. In Spain, the Darío's poetry was vindicated in the 1960s by the group of poets known as the «newest», and especially by Pere Gimferrer, who titled one of his books, in clear homage to the Nicaraguan, Los raros.

Dario has rarely been translated, although many of his works have been translated into French and English, such as some of his poems, by his compatriot Salomón de la Selva.

In Argentina, a station of the General Urquiza Railroad in the province of Buenos Aires was named after him. In Spain, a station on line 5 of the Madrid Metro bears his name.

Tributes

- Order of Cultural Independence «Rubén Darío»

- Maximum cultural distinction granted by the Presidency of the Republic of Nicaragua to characters or institutions that have been highlighted by their contributions in different fields of Nicaraguan or foreign culture.

- National Prize “Rubén Darío”

- The Rubén Darío National Award was regulated in Nicaragua by Decree No. 5, approved on January 2, 1942 and published in Nicaragua The Gaceta No. 7 of 14 January 1942.

- This decree (n. 5) was repealed and replaced everywhere by Decree No. 3, adopted on 16 December 1942 and published in The Gaceta No. 4 of 11 January 1943.

- This award was replaced by International Poetry Prize Ruben Darío since 2009.

- International Poetry Prize Ruben Darío

- Called every year by the government of the Republic of Nicaragua through the Nicaraguan Institute of Culture.

- Award for Academic Excellence “Rubén Darío”

- The Rubén Darío Academic Excellence Award recognizes the effort, perseverance and constancy in academic excellence. It is delivered every year, within the framework of the working session of the Regional Council for Student Life of Central America and the Dominican Republic (CONREVE). It is the highest award given by the Central American University Council (CSUCA) to the most outstanding students between the 21 universities in Central America and the Dominican Republic that make up that regional entity.

- Biennial Prize “Rubén Darío” and Poetry and Prose Competition “Rubén Darío”

- Granted by the Central American Parliament (PARLACEN).

- "Rubén Darío" Award for Poetry in Castellano

- The City of Palma convenes the Rubén Darío de Poesía Award in Castellano.

- International Prize for Literature «Rubén Darío»

- Called by Sial Pigmalión Editorial Group.

Work

Poetry (first editions)

- Open. Santiago de Chile: Imprenta Cervantes, 1887.

- Rimas. Santiago de Chile: Imprenta Cervantes, 1887.

- Blue.... Valparaíso: Imprenta Litography Excelsior, 1888. Second edition, expanded: Guatemala: Printing The Union1890. Third edition: Buenos Aires, 1905.

- Epic song to the glories of Chile. Editor MC0031334: Santiago de Chile, 1887.

- First notes, [ Epistles and poems, 1885]. Managua: National typography, 1888.

- Profanes and other poems. Buenos Aires, 1896. Second edition, expanded: Paris, 1901.

- Songs of life and hope. The swans and other poems. Madrid, Type of Archives and Libraries Magazines, 1905.

- Oda to Mitre. Paris: Imprimrie A. Eymeoud, 1906.

- The wandering chant. Madrid, File Type, 1907.

- Autumn Poem and Other Poems, Madrid: Library «Ateneo», 1910.

- I sing to Argentina and other poems. Madrid, Spanish Classic Printer, 1914.

- Lira póstuma. Madrid, 1919.

Prose (first editions)

- The weird ones.. Buenos Aires: Workshops of "La Vasconia", 1896. Second edition, increased: Madrid: Maucci, 1905.

- Contemporary Spain. Paris: Bookshop of the Vda. de Ch. Bouret, 1901.

- Pilgrimage. Paris. Bookstore of the Vda de Ch. Bouret, 1901.

- The caravan passes. Paris: Brothers Garnier, 1902.

- Solar lands. Madrid: Type of the Archives Magazine, 1904.

- Reviews. Madrid: Fernando Fe Library, 1906.

- The trip to Nicaragua and Intermezzo tropical. Madrid: Biblioteca «Ateneo», 1909.

- Letters (1911).

- Everything to the flight. Madrid: Juan Pueyo, 1912.

- Ruben Darío's life written by himself. Barcelona: Maucci, 1913.

- The island of gold (1915) (unfinished).

- History of my books. Madrid, Bookshop of G. Pueyo, 1916.

- Spread Prose. Madrid, Latin World, 1919.

Complete Works

- Complete works. Alberto Ghiraldo's prologue. Madrid: Latin World, 1917-1919 (22 volumes).

- Complete works. Alberto Ghiraldo and Andrés González Blanco edition. Madrid: Rubén Darío Library, 1923-1929 (22 volumes).

- Full poetic works. Madrid: Aguilar, 1932.

- Complete works. M. Sanmiguel Raimúndez and Emilio Gascó Contell. Madrid: Afrodisio Aguado, 1950-1953 (5 volumes).

- Poetry. Edition of Ernesto Mejía Sánchez. Preliminary study by Enrique Ardenson Imbert. Mexico: Fund for Economic Culture, 1952.

- Complete poetry. Edition of Alfonso Méndez Plancarte. Madrid: Aguilar, 1952. Revised edition, by Antonio Oliver Belmás, in 1957.

- Complete works. Madrid: Aguilar, 1971 (2 volumes).

- Poetry. Edition of Ernesto Mejía Sánchez. Caracas: Ayacucho Library, 1977.

- Complete works. Madrid: Aguilar, 2003. (Despite the title, it only contains his works in verse. Play the edition Complete poetry of 1957).

- Complete works. Edition of Julio Ortega with the collaboration of Nicanor Vélez. Barcelona: Gutenberg Galaxy, 2007. ISBN 978-84-8109-704-7. The publication of three volumes is expected (I PoetryII ChroniclesIII; Counts, literary criticism and prose varia), of which only the first has appeared so far.

Passive Bibliography

- Fernández, Teodosio: Ruben Darío. Madrid, History 16 Quorum, 1987. Collection «Protagonists of America». ISBN 84-7679-082-1.

- Ferreiro Villanueva, Cristina: Keys of Rubén Darío's poetic work. Madrid: Ciclo Editorial, 1990. ISBN 84-87430-79-1.

- Litvak, Lily (ed.): Modernism. Madrid: Taurus, 1986. ISBN 84-306-2081-8.

- Login Jrade, Cathy: Rubén Darío and the romantic search of the unit. From modernist recourse to esoteric tradition. Mexico: Fund for Economic Culture, 1986. ISBN 986-16-2480-7.

- Ruiz Barrionuevo, Carmen: Ruben Darío. Madrid: Synthesis, 2002. ISBN 84-9756-048-5.

- Salinas, Pedro: The Poetry of Rubén Darío. Barcelona: Peninsula, 2005. ISBN 84-8307-650-0.

- Vargas Vila, José María: "Rubén Darío". 1917.

- Ward, Thomas: "The Religious Thought of Ruben Darius: A Study of Profanous profanes and Songs of life and hope». Revista Iberoamericana No. 55 (January-June 1989): 363-75.

- "Rubén Darío and the modernists between two worlds." Svět literatury / The World of Literature (2016) (special number): 51-139. ISSN 0862–8440 (impresa), 2336–6729 (online). Available online.

References and notes

- ↑ a b "Rubén Darío, the prince of the Castellana Letters", Shorthand.com, consulted on January 10, 2020.

- ↑ Martínez, José María (2009). «Literary Modernism and Religious Modernism: Meetings and Consensors in Rubén Darío». CILHA Notebooks 10 (1). ISSN 1852-9615. "In general, mine (my opinion) coincides with those who see in their Catholicism the basis of their religious attitude and spiritual cosmovision, which in turn includes incursions that go from the serious to the mere pose in other religious doctrines and experiences."

- ↑ Geirola, Gustavo (2015). The desired East. Lacanian approach to Rubén Darío. Lulu.com. p. 199. ISBN 978-09-904-4452-7.

- ↑ Arias Careaga, Raquel (2002). "Propologist." Tales of Darius. Madrid: Akal. p. 21. ISBN 84-460-1526-9. Consultation on 10 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d Fernández, Teodosio: Ruben Darío. Madrid, History 16 Quorum, 1987. Collection «Protagonists of America», ISBN 84-7679-082-1, p. 10.

- ↑ a b «The tragic life of Rosa Sarmiento (1840-1895): mother of Reuben Darius,» El Nuevo Diario23 January 2011.

- ↑ Darius, Reuben. Autobiography. Gold of Mallorca. Introduction of Antonio Piedra. Madrid: Mondadori, 1990, ISBN 84-397-1711-3, p. 3.

- ↑ Darius, Reuben (1991). Ruben Darío's life, written by himself. Caracas: Ayacucho Library. p. 9. ISBN 980-276-165-6. Consultation on 11 September 2013.

- ↑ Darius, Reuben (1991). Ruben Darío's life, written by himself. Caracas: Ayacucho Library. p. 12. ISBN 980-276-165-6. Consultation on 11 September 2013.

- ↑ Darius, Reuben. op. cit., p. 18.

- ↑ The influence of Francisco Gavidia was decisive because it was this author who discovered Darius French poetry. The Nicaraguan wrote, History of my books:

Years ago, in Central America, in the city of San Salvador, and in the company of the poet Francisco Gavidia, my teenage spirit had explored the immense salvation of Victor Hugo and had contemplated his divine ocean where everything was contained...

- ↑ Rubén Darío and Narcissus Tondreau, close friends in Chile.

- ↑ "Rubén Darío in Chile: some notes against the problem of the beginnings of Spanish-American Literary Modernism." Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Consultation on 24 June 2011.

- ↑ Contreras, Francisco (2012). Rubén Darío: his life and his work (corrected edition and increased by Rivera Montealegre, Flavio). Bloomington, USA. U.S.: Unive. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4697-7960-7. Consultation on 2 September 2015.

- ↑ Revenez, Francisco Javier (January-April 1997). "Vitalism and sensitivity of Rubén Darío: current valuation". Anthropos Magazine – Knowledge Footprints (170-171): 64 et seq. ISSN 0211-5611. Consultation on 20 May 2014.

- ↑ His biographer Edelberto Torres recounts what happened:

He is the brother of Rosario, a man without any kind of scruples, Andrés Murillo; he knows the intimate drama of his sister, who incapacitates her to be the wife of any punctured local gentleman. In addition, the 'house' of Rosario has transcended the public, and then Murillo conceives the plan to marry Ruben with his sister. He knows the timorate character of the poet and the abulia that is reduced under the action of alcohol. Bring the plan to your sister and she accepts it. At the end of a cursed day, Rubén is delivered with innocence and honesty to the loving requiebros with Rosario, in a house opposite the lake, neighborhood of Candelaria. Suddenly the brother-in-law appears, which unsubstantiated a revolver and insolent words threatens to finish him if he doesn't marry his sister. The poet, puzzled and overcrowded of fear, offers to do so. And as everything is prepared, the priest arrives at the house of Francisco Solórzano Lacayo, another brother-in-law of Murillo: he has swallowed whisky to Rubén and in that state he proceeds to religious marriage, which is only authorized in Nicaragua, on March 8, 1893. The poet does not realize the yes he has pronounced. The embotment of his senses is complete, and when, at dawn, he regains reason, he is on the conjugal bed with Rosario, under the same blanket. Neither protest nor complain; but he realizes that he has been a victim of perfidy, and that that event is going to weigh as a drag of misfortune in his life.Cited in "Cronology", in the electronic journal Dariana.

- ↑ Count, Carmen. Rubén Darío and the dramatic persecution of Rosario Murillo, p. 604.

- ↑ «Rosario Murillo: The Nicaraguan wife of Darius Archived on February 8, 2017 at Wayback Machine.», at Elnuevodiario.com.ni. Consultation on 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Darius, Reuben. op. cit., p. 74.

- ↑ Jáuregui, Carlos A. (1998). «Calibán, icon of 98. With regard to an article by Rubén Darío». Revista Iberoamericana 184-185. Consultation on August 2008.

- ↑ Mayor Cruchaga, Francisco Javier (1993). Beloved Nervo. Santiago, Chile: Gráfica Andes. p. 11. Consultation on 30 January 2016. "In the year 1900 (Friend Nervo) traveled to Paris, on the occasion of the Universal Exhibition and there he met Darío, with whom he would join a good friendship (even lived together for a while, in the Montmartre district).

- ↑ « Serrano Street House, No. 27 cto. Pral. Izda. In Madrid six June of the year a thousand nine hundred eight; assembled Don Rubén Darío, Minister of Nicaragua, with a credential letter dated in Managua on 21 December 1907, signed by President S. Zelaya and José D. Gámez who leased him the position in Madrid (...) as a tenant; and Don José María Romillo and Romillo of 34, neighbor of Madrid with class 2 2304, issued in Madrid on 12 October 1907, as owner we have hired the lease of the fourth pral. House No. 27 Serrano Street sits in this court of four months and price of two thousand four hundred pesetas each year, paid for months. The conditions will be stamped on the back, written or printed, and in case of exceptional extension, in separate folds, without seal, attached to the present. Formalized this contract, and for the record, we signed it by duplicate. Date ut above». Reference: [1].

- ↑ "Rubén Darío, has the honour to greet the Lord Don José María Romillo and Romillo and communicates to him, according to the contract, that within ten days he has at his disposal the fourth (apartment), in which he has inhabited, Calle de Serrano, n.o 27. Madrid, February 24, 1909. Rubén Darío». Source: Complutense Digital Collection. Archive Rubén Darío: Document number 405. Greeting from Rubén Darío addressed to José María Romillo and Romillo.

- ↑ Fernandez, Teodosio. op. cit., p. 126.

- ↑ Fernandez, Teodosio. op. cit., p. 129.

- ↑ Darius, Reuben. op. cit., p. 127.

- ↑ Parish, H. R. (1942). «The way of death: Psychological study of the subject of death in the poems of Rubén Darío». Revista Iberoamericana 5 (9): 71-86.

- ↑ Torres, Edelberto (1956). Rubén Darío's dramatic life. Mexico: Bibliographies Gandesa. p. 329.

- ↑ Tovar, Paco (1987). "Rubén Darío has drunk, living Darius." Scriptura (3): 114-132.

- ↑ So decisive are the influences that Parnasianism and Symbolism had in the work of Darius, and in Modernism in general, that authors like Ricardo Gullón have spoken of a "Parnasian direction" and a symbolist direction" of Modernism (ref.: Ricardo Gullón, Addresses of Modernism. Madrid: Editorial Alliance, 1990. ISBN 84-338-3842-3.

- ↑ Soto Vergés, Rafael. «Rubén Darío y el neoclasicismo (the aesthetics of Open), in Hispanic American CuadernosNo. 212-213 (August-September 1967).

- ↑ Darío was a great admirer of Bécquer, whom he had known since at least 1882. Ref.: Collantes de Terán, Juan. "Rubén Darío", in Luis Íñigo Madrigal (ed.), History of Hispanic American Literature, Volume II: From Neoclasicism to Modernism. Madrid: Chair, 1987, ISBN 84-376-0643-8, pp. 603-632.

- ↑ López, Ana María (1977). "Five poems by Rubén Darío in World Magazine." Hispanic American Literature Analyses (6): 291-306. ISSN 0210-4547. Consultation on 12 June 2012.

- ↑ Zepeda-Henríquez, Eduardo (1967). Study of the poetics of Rubén Darío. Mexico: Printing Polychrome. p. 92.

- ↑ Navarro Tomás, Tomás. Spanish metric, Barcelona: Labor, 1995, ISBN 84-335-3511-0, p. 420.

- ↑ In his poem «The Inner Kingdom», by Profanous profanesDarius even comes to ironize about his predilection by this type of lexicon:

and among the enchanted branches, papemores

whose singing extasiated from love to bulbules...

(Papemor: rare bird; bulbules: russians). - ↑ The poem, which belongs to your book The hidden paths (1911), starts like this:

Throw the neck to the swan of deceitful plumage

which gives its white note to the blue of the fountain;

He passes his grace no more, but does not feel

the soul of things and the voice of the landscape. - ↑ Salinas, Pedro. «The swan and owl. Notes for a History of Modernist Poetry”, in Spanish literature. 20th century, Madrid: Editorial Alliance, 1970; pp. 46-66.

- ↑ Ferreiro Villanueva, Cristina: Keys of Rubén Darío's poetic work. Madrid: Ciclo Editorial, 1990, ISBN 84-87430-79-1.

- ↑ "The senses are the absolute lords of the lyrical love of Reuben, during his first time" (Salinas, Peter. The Poetry of DariusBarcelona, Peninsula, 2004; p. 48).

- ↑ « Pleasure is the central theme of Profanous profanes. Only that pleasure, because it is a game, is a rite of which sacrifice and sorrow are not excluded" (Peace, Octavian, "The Caracol and the Mermaid", in Darius, Reuben. Anthology1999, p. 37. See the bibliography).

- ↑ Salinas, Pedro. op. cit., p. 55.

- ↑ As an example, the following verses of the poem cited can be cited: Your sex founded / with my strong sex, / founding two bronzes.

- ↑ Gullón, Ricardo in his "Introduction" to Darius, Reuben. Pages chosen. Madrid: Chair, 1988, p. 19.

- ↑ Sometimes both themes appear related, as in the poem "Divagation" Profanous profanes.

- ↑ The idea that Darius forged about pitagorism has less to do with what was the true thought of Pythagoras than with the image that gave it a classic of esotericism, The Great Initiates: A Study of the Secret History of ReligionsEdouard Schuré's work. In this book, Pythagoras was described as an initiate in the hidden wisdom, along with other real or mythical names, of the history of religions (such as Rāma, Krishna, Hermes, Moses, Orpheus, Plato and Jesus).

- ↑ Like Octavio Paz, in The sons of lemon, and Cathy Login Jrade, in his work on the influence of esoteric thought in the poetry of Darius (see bibliography).

- ↑ In later editions, this work has been edited with the title Autobiography. It is a very useful book to know the author's biographical trajectory, although it is not exempt from inaccuracies (voluntary or not).

- ↑ Pupo-Walker, Enrique (1972). «Notes on the formal features of the modernist story». Hispanic American Literature Analyses (Universidad Complutense de Madrid) 1: 473. ISSN 0210-4547.

- ↑ Cited in Cano, José Luis Cano. Spanish of three worlds. Madrid: Seminars and Editions S. A., 1974, ISBN 84-299-0064-0, p. 84.

- ↑ Pio Baroja. Men and flies. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Consultation on 30 May 2016.

- ↑ Pig, Luis. «Experience in Rubén Darío», in Prosa I, Madrid: Siruela, 1994, ISBN 84-7844-214-6, pp. 711-721.

- ↑ «Discourse to the Almon by Federico García Lorca and Pablo Neruda on Rubén Darío», in García Lorca, Federico. Complete works III. Prosa, Barcelona: Gutenberg Galaxy, 1996, ISBN 84-8109-090-5, pp. 228-230.

- ↑ Peace, Octavian. art. cit., p. 27.

- ↑ See this website. Archived on 25 March 2006 at Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Rubén Darío National Award is regulated."

- ↑ "Derogation of Executive Decree No. 5, on the national prize "Rubén Darío". Legislation.asamblea.gob.ni. Consultation on 19 June 2021.

- ↑ http://www.ucr.ac.cr/noticias/2014/08/28/student-centroamericanos-y-de-caribe-reciben-recognition.html.

- ↑ http://parlacensubsedenicaragua.blogspot.com/2013/02/bases-del-primer-concurso-de-poesia-y.html.

- ↑ http://becas.universia.es/ES/beca/117978/premio-ruben-dario-poesia-castellano.html.

- ↑ http://www.pigmalionedypro.es/ • http://pigmalionedypro.blogspot.com/ Archived on April 17, 2018 at Wayback Machine..

- ↑ http://www.memoriachilena.cl/items/document_detalle.asp?id=MC0031334.

Contenido relacionado

Max Aub

Fernando Quinones

Martin Luis Guzman