Royal Alcazar of Madrid

The missing Real Alcázar of Madrid was a royal palace of the Hispanic monarchy until 1734, the year in which it was destroyed by a fire of uncertain origin. It was located on the site where the Royal Palace of Madrid currently stands (sometimes called "Palacio de Oriente", due to its location in the Plaza de Oriente). Built as a Muslim fortress in the IX century, the building was expanded and improved over the centuries, especially from the XVI century when it became a royal palace according to the choice of Madrid as the capital of the Spanish Empire. Despite this, this great construction continued to retain its original name of fortress.

The first major expansion undertaken in the building was carried out in 1537, commissioned by Emperor Charles V, but its final exterior appearance corresponds to the works carried out in 1636 by the architect Juan Gómez de Mora, promoted by the king. Philip IV.

Famous both for its artistic wealth and for its irregular architecture, it was the residence of the Spanish royal family and seat of the Court from the Trastámara dynasty, until its destruction in a fire on Christmas Eve 1734, in the time of Philip V. Many of its artistic treasures were lost, including more than 500 paintings, although others could be rescued (such as Las meninas by Velázquez).

History

Origins

There is extensive documentation on the plan and exterior appearance of the building between the XVI century and 1734, when disappeared in a fire: numerous texts, engravings, plans, models and paintings. However, the images of its interior are very scarce and the references about its origin are not abundant either.

The first known drawing of the Alcázar was made by the Flemish painter Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen around the year 1534, three decades before the designation of Madrid as the capital of Spain. It shows a castle articulated in two main bodies, which may perhaps correspond, at least partially, to the structure of the Muslim fortress on which it sits.

This primitive fortification was built by the Cordoban emir Muhammad I (852-886), on an undetermined date between the years 860 and 880. It was the central core of the Islamic citadel of Majrit, a walled enclosure of approximately four hectares., integrated, in addition to the castle or hisn, by a mosque and the house of the governor or emir.

Its enclave, in steep terrain, must have been located somewhere near the heights of Rebeque. Currently there is no evidence since it served as a quarry for the new Christian buildings. Its location had great strategic value, since it allowed surveillance of the Manzanares river route. This was key in the defense of Toledo, in the face of the frequent incursions of the Christian kingdoms into the lands of Al-Andalus.

After the conquest of Islamic Madrid in 1083 by Alfonso VI and given the need to accommodate the itinerant Castilian court in its numerous rooms in the city, a new fortress was built, north of the first walled enclosure. That is to say, the Islamic fortress was most likely never located under the current Royal Palace, as many chronicles point out, which are wrong and which have copied each other until it is the most widespread theory, but refuted by history and archaeology.

It is likely that the castle was the result of the evolution, in that same place, of different previous military constructions: first, an observation watchtower and, later, perhaps a small fort.

The old Christian castle was subject to different extensions over time, leaving the original structure integrated into the additions. This can be seen in some engravings and paintings from the XVII century, in which they appear on the western façade (the one facing the Manzanares River), semicircular cubes that clash with the general design of the building.

The Trastámara

The Trastámara dynasty converted the building into its temporary residence, so that, at the end of the 15th century, the Alcázar of Madrid was already one of the main fortresses of Castile and the Madrid town was the usual headquarters for the convocation of the Cortes of the Kingdom. In keeping with its new function, the castle incorporated the name of royal in its toponym , indicative of its exclusive use by the Castilian monarchy.

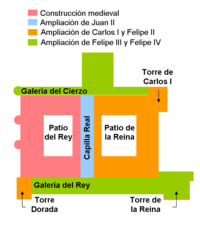

Henry III promoted the erection of different towers, which changed the appearance of the building, giving it a more palatial air. His son, John II, built the Royal Chapel and added a new room, known as the Rich Room, for its sumptuous decoration. These two new elements, built next to the eastern façade, meant expanding the surface of the primitive castle by approximately 20% more.

Henry IV was one of the kings who frequented the place the most. He resided in the Alcázar for long periods and Juana la Beltraneja, his only daughter, was born there on February 28, 1462.

In 1476, the followers of Juana la Beltraneja were besieged in the building, in the context of disputes for control of the throne of Castile with Isabel la Católica. The facility suffered considerable damage during this siege.

Charles I

The Real Alcázar of Madrid once again suffered significant damage during the War of the Communities of Castile, which lasted from 1520 to 1522, during the time of Charles I.

In view of its condition, Charles I decided to expand the building, in what can be considered the first important work in the history of the Alcázar. This remodeling is probably related to the emperor's desire to permanently establish the Court in the town of Madrid, something that did not materialize until the reign of Philip II. This is what different researchers maintain, in the case of Luis Cabrera of Córdoba (XVI century), who, in a writing referring to this last monarch, is expressed in the following terms:

The Catholic King [by Felipe II], judging incapable the room of the city of Toledo, executing the desire of the emperor his father [by Carlos I] to put his Court in the Villa of Madrid, determined to place in Madrid his real seat and government of his monarchy.

From this perspective we understand the efforts of Charles I to provide the town with a royal residence, at the level of the needs of a modern state or, at least, what he was accustomed to before his arrival in Castile.. Instead of demolishing the uncomfortable and outdated medieval castle, an initiative that could have been criticized as too radical, the emperor made the decision to use it as a base for the construction of a palace. The new construction continued to bear the name of the pre-existing fortress, Real Alcázar of Madrid, despite the fact that, centuries ago, it had already lost its military function.

The works began in 1537, under the direction of the architects Luis de Vega and Alonso de Covarrubias, who renovated the old rooms, articulated around the King's Courtyard, already existing in the medieval castle. However, his most valuable contribution was the construction of new rooms for the queen, distributed around the Queen's Courtyard, of new construction. Likewise, the so-called Tower of Charles I was built, in one of the corners of the northern façade, the one that overlooks the current Sabatini Gardens. These new additions meant doubling the original surface area of the building.

The project was dominated by unmistakable Renaissance features, very visible in the cases of the main staircase and the aforementioned Courtyards of the King and Queen, marked by continuous semicircular arches and supported by columns that gave lightness to the building.

The expansion promoted by Charles I was the first major work carried out in the Alcázar, which was followed by numerous reforms and remodeling that took place, practically uninterrupted, until the destruction of the building in the 19th century XVIII.

Philip II

Philip II continued with the expansions. Already in his time as prince, he showed great interest in the works promoted by his father, Emperor Charles I. As king, he promoted the definitive adaptation of the building into a palatial residence, especially from 1561, when he decided to establish the Court permanently. permanent in Madrid.

The monarch ordered the renovation of his chambers, as well as other rooms, and put special effort into the decoration of the rooms, work that was entrusted to carvers, glassmakers, carpenters, painters, sculptors and other craftsmen and artists, many of them arriving from the Netherlands, Italy and France. The works, which lasted from 1561 to 1598, were initially directed by Gaspar de la Vega.

However, the Golden Tower, the king's most relevant contribution to the Alcázar, was due to the architect Juan Bautista de Toledo, his replacement in the execution of the works. This tower presided over the southwestern edge of the Alcázar and was topped with a slate spire, whose layout recalls the shape of the corner towers of the Monastery of El Escorial, which was being built simultaneously in the Guadarrama mountain range.

During the reign of Philip II, the Real Alcázar of Madrid underwent, as has been noted, its definitive conversion into a royal palace. Regarding its interior, the part between the two primitive towers of the southern façade adopted a more ceremonial air, while the service area was arranged in the northern wing.

The western area was reserved for the king's quarters, facing the queen's quarters on the east. Both areas were separated by two large patios, according to the structure conceived by Alonso de Covarrubias, in the time of Charles I. This distribution of the different functionalities remained practically unchanged until the fire of 1734.

Philip II was also responsible for the construction of the Royal Armory, demolished in 1894. It occupied the place where the crypt of the Almudena Cathedral stands today and was part of the Royal Stables complex, dependent on the fortress..

Philip III, Philip IV and Charles II

Despite the impetus given to the building by Philip II, the Real Alcázar presented, at the end of his reign, a heterogeneous appearance. Its main façade, located to the south, integrated medieval elements, which clashed with the monarch's additions. The clash of styles was very visible with regard to the Golden Tower, built by the king, and the two large towers of the Muslim castle, whose arrangement in cubes, with practically no openings, took away from the lightness of the whole.

When Philip III, son of Philip II, came to the throne, the southern façade became the monarch's main endeavor. His project, entrusted to Francisco de Mora, consisted of harmonizing the south façade based on the architectural characteristics of the aforementioned Golden Tower. The remodeling of the queen's rooms was also due to this architect.

However, the works on the façade were finally carried out by Juan Gómez de Mora, his nephew, who introduced important innovations to his uncle's design, in keeping with the baroque currents of the time. The new layout began to be carried out in 1610 and was extended to the reign of Philip IV, until 1636, when the façade that survived until the fire of 1734 was completed and the works to enclose the outer plaza were carried out.

The complex gained luminosity and balance, thanks to a succession of windows and columns articulated from two symmetrical towers. In addition to the aforementioned southern façade, the remaining façades were remodeled, except for the western one, which continued to be that of the old medieval castle. In 1680, works were carried out by Bartolomé Hurtado.

Curiously, it was Philip IV who gave the building its most harmonious layout, despite his detachment from it. The monarch refused to live in the fortress and ordered the construction of a second palace, Buen Retiro, which has also disappeared. It was built outside the walls, to the east of the city, on the land now occupied by El Retiro Park.

The project started by Philip III and completed by Philip IV continued during the reign of Charles II, through different adjustments. The Queen's Tower, located on the southeastern flank, was topped with a slate spire, to maintain symmetry with the Golden Tower, erected in the time of Philip II, at the other end. Likewise, the plaza that emerged at the foot of the southern façade incorporated different rooms and galleries.

Philip V

Philip V proclaimed himself king of Spain on November 24, 1700, in an event held in the southern plaza of the palace, coinciding, in general terms, with the current Plaza de la Armería.

The Real Alcázar of Madrid, the austere building that was to be his residence, clashed head-on with the French taste that had permeated the monarch's life, from his birth in Versailles in 1683 until his arrival in Spain in 1700. Hence that the reforms he promoted in the palace affected, for the most part, its interior.

The main rooms were redecorated, following the guidelines of French palaces. Queen Marie Louise of Savoy directed the reforms, with the help of her senior chambermaid, Anne Marie de la Tremoille, princess of the Ursines, her right hand in these tasks. The latter set the guidelines in the execution of the works, regardless of any bureaucratic procedure.

The interior remodeling of the Álcazar was initially carried out by the architect Teodoro Ardemans, replaced, in a second phase, by the French architect René Carlier.

The fire of 1734

On Christmas Eve 1734, with the Court moved to the El Pardo Palace, a terrifying fire broke out in the Real Alcázar of Madrid. The fire, which could have originated in a room of the Corte painter Jean Ranc, spread rapidly, without being able to be controlled at any time. It spread over four days and was of such intensity that some objects of Silver was melted by the heat and the remains of metal (along with precious stones) had to be collected in buckets.

According to the story of Félix de Salabert, Marquis of la Torrecilla, made days after the event occurred, the first warning was given at approximately 00:15, by some sentinels who were on guard. The festive nature of the day prevented the alert from immediately spreading to the street and even the ringing of the bell towers was initially ignored, since people "thought they were matins" (prayers before dawn), in words of the aforementioned author. The first to collaborate, both in extinguishing the fire and in rescuing people and objects, were the friars of the San Gil congregation.

For fear of looting, the initial reaction was not to open the doors of the Alcázar, which reduced time for the eviction when it was already forced. A huge effort was made to recover the religious objects that were kept in the Royal Chapel, as well as cash and jewels of the Royal Family, such as the Pilgrim Pearl and the El Estanque diamond. Some chest with coins had to be thrown out of a window.

The recovery of the numerous paintings from the Alcázar was left in the background, given the difficulties involved due to their size and location at various heights and in multiple rooms. Some of these paintings were embedded in the walls. Hence, a good number of the paintings that were kept in the building at that time were lost (such as The Expulsion of the Moriscos by Velázquez), and others (such as Las Meninas) were saved by being unnailed from the frames and thrown out of the windows. However, a part of the pictorial collections had previously been transferred to the Buen Retiro Palace, to preserve it from the renovation works that were taking place inside the Real Alcázar, which saved them from probable destruction. On the other hand, the fire also destroyed the American collections that the kings of Spain had been building, which included the pieces offered to the Crown by the conquistadors.

Once the fire was extinguished, the building was reduced to rubble. The walls that remained standing had to be demolished, given their state of deterioration. Four years after his disappearance, in 1738, Philip V ordered the construction of the current Royal Palace of Madrid, whose works lasted three decades. The new building was inhabited for the first time by Charles III in 1764.

Features

Despite the efforts made to give the building a harmonious layout, the modifications, extensions and reforms carried out over the centuries did not give it a homogeneous appearance. French and Italian visitors criticized that the facades were irregular and the interior layout was labyrinthine. Many of the private rooms were dark and had no windows, which is explained by the hot climate of Madrid (in which shade was sought) and also by the scarcity of glass. Still at the beginning of the 18th century, many palace windows were closed with lattices to hide the lack of glass.

The first asymmetry came from its western façade, which, being located on the edge of the ravine formed by the ravine of the Manzanares valley, was the least visible from the urban area of Madrid. But, at the same time, it was the first one seen by travelers entering the city through the Segovia bridge.

This façade was the one that underwent the least number of renovations and, consequently, the one that most denoted the medieval origin of the building. It was entirely made of stone, with four cubes or semicircular towers, although it is true that larger and more numerous windows had been made than those arranged in the primitive fortress. The four cubes were topped with conical slate spiers, similar to those of the Alcázar of Segovia, which softened the military air of the complex.

The remaining facades were built in red brick and granite (Toledan quartz), which gave the building a very characteristic coloring of the traditional architecture of Madrid, in which these two materials, so abundant in the area of influence of the city (clay is abundant on the banks of the Manzanares River and granite stone in the nearby Guadarrama mountain range).

The main entrance was on the southern façade, which was especially problematic in the different renovations undertaken, as it was dominated by two large quadrangular volumes, built in the Middle Ages. Both bodies broke the longitudinal line of the façade, which joined the Golden Tower, erected in the times of Philip II, with the Queen's Tower, corresponding to the reforms of Philip III and Philip IV.

With the design of Juan Gómez de Mora, the aforementioned towers were hidden, achieving a greater balance of the whole, as can be seen in the drawing by Filippo Pallota, from 1704. This architect also harmonized the appearance of the Golden Towers and of the Queen, by placing a pyramidal spire on the second, identical to that of the first.

The Real Alcázar of Madrid was rectangular in plan. Its interior, articulated around two large patios, was also organized asymmetrically. The King's Courtyard, located to the west in the part corresponding to the medieval castle, was smaller than the Queen's Courtyard, which, located on the opposite side, distributed the rooms built during the expansion of Charles I. Between them, the Chapel stood. Real, fruit of the impulse of the Trastámara, specifically, of King Juan II of Castile. For a long time the patios were open to the people, and all kinds of items were sold there as in a market, a custom that surprised foreign travelers.

The Real Alcázar, painting gallery

In the Real Alcázar of Madrid there were a huge number of works of art, of which references have remained thanks to the inventories carried out in the years 1600, 1636, 1666, 1686 and 1700, in addition to those carried out after the fire of 1734 and after the death of Philip V (1683-1746).

It is estimated that, at the time of the fire, nearly two thousand paintings were kept in the palace, including originals and copies, of which more than five hundred were lost. The approximately one thousand paintings that could be rescued were kept in different buildings in the days after the event, including the Convent of San Gil, the Royal Armory and the houses of the Archbishop of Toledo and the Marquis of Bedmar. An important part of the Alcázar art gallery had been provisionally moved to the Buen Retiro Palace to facilitate the execution of some works, which was safe from the fire.

Among the lost works, one of the most valuable, both in terms of workmanship and its historical value, was The Expulsion of the Moriscos, by Diego de Silva y Velázquez, which won him in the competition In 1627 he won the position of chamber usher, a decisive step in his career, since it allowed him to make his first trip to Italy. Velázquez also had an equestrian portrait of the king, and three of the four paintings from a mythological series he painted around 1659 were also lost (Apollo and Marsyas, Adonis and Venus, and Psyche and Cupid). He only recovered from this series Mercury and Argos. The famous painting Las Meninas , which he hung in an office on the ground floor, could be rescued but suffered a perforation in the cheek of its protagonist, the Infanta Margarita. This damage was skillfully repaired at the time, and required no further retouching when the painting was restored in 1984.

Another of the great painters whose works were lost was Rubens. Among its losses we can mention a beautiful equestrian portrait of Philip IV especially loved by the sitter, and which occupied a privileged place in the Hall of Mirrors, opposite the famous portrait of Titian Charles V in Muhlberg. A good copy of Rubens' destroyed painting remains in the Uffizi in Florence. Rubens' The Abduction of the Sabine Women, or the twenty works that adorned the Ochavada Piece, were also lost.

The series of The Twelve Caesars was lost from the aforementioned Titian, present in the Salon Grande, currently known from copies and a series of engravings by Aegidius Sadeler II. Two of the four Furies that were in the Hall of Mirrors were also burned (the other two are in the Prado Museum). In addition to those mentioned, an invaluable collection of authors was lost with works that (according to inventories) were by Tintoretto, Veronese, Ribera, Hieronymus Bosch, Brueghel, Sánchez Coello, Van Dyck, El Greco, Annibale Carracci, Leonardo da Vinci, Guido Reni, Rafael de Urbino, Jacopo Bassano, Correggio... among many others.

Annex areas

The successive expansions undertaken at the Real Alcázar of Madrid throughout history not only affected the building itself, but also its surroundings, with the construction of a series of annexes.

To the south of the Alcázar, the Royal Stables were built, where the offices of the Royal Armory were integrated. In its northern and western part, the Plaza del Picadero and the Gardens or Huerto de la Priora extended, which connected the palace with the Royal Monastery of La Encarnación. Towards the east, the Treasure House was built.

Treasure House

This name was used to designate an architectural complex, intended for different services, which consisted of two main areas: the Trade Houses and the new kitchens.

Its works, which began in 1568, in the time of Philip II, were carried out based on a design that initially contemplated an independent construction, but which was finally annexed to the eastern façade of the Alcázar, in such a way that there was direct communication between both nuclei.

In the XVII century, a passage was built that linked the Treasure House with the Royal Monastery of La Encarnación, so that the kings could access the aforementioned religious building directly from the palace.

The Treasure House came to house the Royal Library, the predecessor of the National Library, at the initiative of King Felipe V. The complex, which survived the fire of the Alcázar of 1734, was demolished by order of José I, who intended to create a large square next to the eastern façade of the Royal Palace.

The basements, floors and remains of walls of the building were discovered in the XX century during the remodeling works of the Plaza de Oriente, made in 1996 by Mayor José María Álvarez del Manzano. Despite their historical importance, the vestiges were destroyed.

Royal Stables and Royal Armory

In the year 1553, Philip II decided to create a complex that would house the Royal Stables, in the vicinity of the Alcázar. It was built at the opposite end of the southern plaza of the palace, in the place now occupied by the crypt of the Almudena Cathedral, without direct communication with the royal residence. The works, directed by the teacher Gaspar de Vega, lasted from 1556 to 1564, the year after which some modifications took place.

The building had a rectangular plan. It had a continuous nave, 80 m long by 10 m wide, divided into two series of columns, with a total of 37, which supported a roof of groin vaults. On both sides of the central aisle, defined by both series of columns, the mangers were located. The Royal Stables consisted of three doors: the main one, made up of a granite stone arch, faced the Royal Alcázar, another was located at the end of the nave and the last one, open to the palace square, was located on the façade. south. The latter was known as the Armory Arch.

In 1563, the monarch ordered the Royal Armory to be installed on the upper floor, which until then was kept in the city of Valladolid, which meant changing the initial design, which reserved that floor for the servants' quarters. In 1567, slate mansard roofs were added, so that the complex was finally made up of three floors.

The building was demolished in 1894, for the construction of the neo-Romanesque crypt of the Almudena Cathedral.

Gardens of the Prioress

The Gardens or Huerto de la Prioress were the result of the remodeling undertaken at the beginning of the XVII century, on the grounds located to the north and west of the Real Alcázar of Madrid, following the founding of the Royal Monastery of La Encarnación in 1611.

Located in the place now occupied by the Cabo Noval Gardens, within the Plaza de Oriente, the site was managed by the aforementioned convent. In the years 1809 and 1810, King Joseph I ordered the expropriation and destruction of the Prioress Garden, as well as the demolition of the blocks of buildings existing in its vicinity, in order to create a large monumental square to the east of the Royal Palace. This project could not materialize until the reign of Isabel II, when the final layout of the current Plaza de Oriente was completed.

Contenido relacionado

Alabaster

Valdunciel Causeway

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia