Rosalind franklin

Rosalind Elsie Franklin (United Kingdom: /ˈɹɒzəlɪnd ˈfɹæŋklɪn/; London, July 25, 1920 - London, April 16, 1958) was a British chemist and crystallographer whose work was instrumental in understanding the molecular structures of DNA. (deoxyribonucleic acid), RNA (ribonucleic acid), viruses, carbon, and graphite. Although his work on carbon and viruses was recognized during his lifetime, his contribution to the discovery of the structure of DNA went largely unnoticed. Because of this, she has been described as a & # 34; wronged hero & # 34;, Rosalind Franklin was the first person to publicly suggest that the phosphate groups of DNA should be on the outside of the molecule. He did it at the time he was working at King's College London, at a conference attended by James Watson "forgotten heroine", "dark lady of DNA& #34;, "feminist icon" and "the Sylvia Plath of molecular biology".

In 1941 he graduated in Natural Sciences from Newnham College, Cambridge, and then enrolled for a Ph.D. in Physical Chemistry under Ronald George Wreyford Norrish, holder of the 1920 Professorship of Physical Chemistry at Cambridge University. Disappointed by Norrish's lack of enthusiasm, she in 1942 accepted a research position with the British Coal Utilization Research Association (BCURA). Research on coal earned her a doctorate at Cambridge in 1945. In 1947 she moved to Paris as a chercheur (postdoctoral researcher) under Jacques Mering at the Laboratoire Central des Services Chimiques de l& #39;État, and became an accomplished X-ray crystallographer. Joining King's College London in 1951 as a Research Associate, she discovered the key properties of DNA, eventually facilitating the correct description of the structure of DNA double helix. Due to disagreements with her director, John Randall, and her colleague Maurice Wilkins, she was forced to transfer to Birkbeck College in 1953.

Franklin is best known for her work on X-ray diffraction imaging of DNA while at King's College London, particularly Photograph 51, taken by her student Raymond Gosling, which led to the discovery of the DNA double helix, for which Francis Crick, James Watson, and Maurice Wilkins shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. Watson suggested that Franklin would ideally have received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, along with Wilkins., but, although there was not yet a rule that prohibited posthumous awards, the Nobel Committee did not usually make posthumous nominations.

Working under the direction of John Desmond Bernal, Franklin led Birkbeck's pioneering work on the molecular structures of viruses. The day before he was to unveil the structure of the tobacco mosaic virus at an international fair in Brussels, he died of ovarian cancer at the age of 37 in 1958. Aaron Klug, a member of her team, continued her research and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1982.

Biography

Franklin was born on July 25, 1920 in London, the second of five children, three of them boys, into a Jewish family that had been in banking for four generations. Her earliest education, up to the age of 18, she received at various prestigious schools, a private school in Norland Place in West London, Lindores School for Young Ladies in Sussex, and St Paul's School. for girls, where she was outstanding in all sports and subjects, including a stay in France with a program that included, in addition to sewing and sports, a debate classroom and, above all, physics and chemistry. She returns home and passes the entrance exam for Newnham College, Cambridge, to study experimental sciences, and specifically chemistry.

He won a scholarship of £30 a year for three years. Her father asked her to donate the money to World War II refugee students. She then studied Natural Sciences at Cambridge, graduating in 1941. She won a scholarship to Cambridge University, in the physical chemistry laboratory, under the supervision of Ronald George Wreyford Norrish, who disappointed her with his lack of enthusiasm. Fortunately, She was offered a research position by the British Coal Research Association (BCURA) in 1942, and her work on coal began. This helped her obtain her doctorate in 1945. She went to Paris in 1947, as a chercheuse (postdoctoral researcher) under the supervision of Jacques Mering at the State Chemical Services Central Laboratory, where she became a accomplished X-ray crystallographer. She joined King's College London in 1951, but was forced to move to Birkbeck College after only two years, due to disagreements with its headmaster John Randall and, moreover, with his colleague Maurice Wilkins. At Birkbeck, J. D. Bernal, head of the Physics Department, offered him a separate research team.

Franklin took X-ray diffraction images of DNA while at King's College, London. These images, which suggested a helical structure and which allowed inferences to be drawn about key details about DNA, were shown by Wilkins to Watson. According to Francis Crick, the research and data obtained by her were key to the determination of Watson and Crick's model. of the DNA double helix in 1953. Watson confirmed this view through a statement of his own at the opening of the Franklin-Wilkins Building in 2000.

Their work was the fourth to be published in a series of three articles on DNA in the journal Nature, the first of which was by Watson and Crick. Watson, Crick, and Wilkins shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1962. Watson pointed out that Franklin should have also been awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, along with Wilkins, which was inconsistent with the rules of the prestigious award that do not allow awards to be given to people already deceased.

Following the completion of his work on DNA, with his own team at Birkbeck College, Franklin led investigations into the molecular structures of viruses, leading to never-before-seen discoveries. Viruses he studied include polio virus and tobacco mosaic virus.Continuing his research, his teammate and later beneficiary Aaron Klug won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1982.

Early years and family origins

Franklin was born at 500 Chepstow Villas, in the London suburb of Notting Hill, into a wealthy and influential British Jewish family. His parents were Ellis Arthur Franklin (1894-1964), a visionary merchant banker liberal politician who taught at Workings Men's College, and Muriel Frances Waley (1894-1976). Rosalind was the eldest daughter and the second in a family of five children: David (1919), her older brother; Colin (1923), Roland (1926) and Jenifer (1929) were her younger siblings.

Herbert Louis Samuel, his father's uncle, was a leading politician, serving as Home Secretary in 1916 (being the first observant Jew in the British Cabinet) and the first British Mandatory High Commissioner for Palestine. His aunt, Helen Caroline Franklin, known in the family as Mamie, was married to Norman de Mattos Bentwich, who was the Solicitor General in the British Mandate.

Rosalind was active in trade union organizations and the women's suffrage movement, and later served on London County Council. Her uncle, Hugh Franklin, was another prominent figure in the suffrage movement, although his actions in it resulted embarrassment to the Franklin family. Rosalind was given her middle name, 'Elsie', in memory of Hugh's first wife, who died in the 1918 flu pandemic. The Working Men's College was home to family activities, where his father taught subjects such as electricity, magnetism, and history of the Great War in the afternoons, where he later held the position of assistant principal. Franklin's parents helped settle Jewish refugees from Europe, who had escaped the Nazis, particularly those from the kindertransport. The Franklins welcomed two Jewish children into their home, one of whom, Evi Eisenstädter (who was nine years old and from Austria), shared a room with Jenifer. Evi's father, Hans Mathias Eisenstädter was imprisoned in Buchenwald, and after his release the family adopted the surname "Ellis".

Since childhood, Franklin displayed exceptional scholastic abilities. At the age of six, she entered the Norland Place School, where her brother was already studying, which was private and was located on Holland Park Avenue, in West London. At this time her aunt Mamie (Helen Bentwich) told her husband, "Rosalind is alarmingly intelligent—she spends all her time studying arithmetic for fun and invariably gets her sums correct." cricket and hockey from a very young age. At the age of nine she was admitted to a boarding school, the Lindores School for Young Ladies in Sussex.The school was close to the coast, as the family wanted an environment suitable for her delicate health. At the age of eleven, she was transferred to St. Paul's School for Girls, where she excelled in science, Latin, and sports. In addition, she learned German and became fluent in French, a language she later it would be useful. She was first in her class and won annual awards. His only academic problems were related to music, so the school's music director, composer Gustav Holst, called his mother on one occasion, to find out if she had suffered from a hearing problem or tonsillitis. With six distinctions, he enrolled in 1938 and won a scholarship to university, the School Leaving Exhibition, of £30 a year for three years, £5 from his grandfather. His father asked him to cede the scholarship to a deserving refugee student.

Cambridge and World War II

Franklin attended Newnham College, Cambridge, in 1938 and studied chemistry within the Natural Science Tripos. One of her teachers was the spectroscopist W. C. Price, who would later become one of her main collaborators at King's College.In 1941, she was awarded Second Class Honors for the final examinations of she. She accepted the distinction as a bachelor's degree in employment skills from him. Cambridge began awarding bachelor's and master's degrees to women in 1947, with women who had graduated earlier receiving them retroactively. In her final year at Cambridge, she met Adrienne Weill, a French refugee who had been a student of Marie Curie; Adrienne was a huge influence on her career and her life. With her she learned to speak French.

Franklin won a research stay, with which he joined the physical chemistry laboratory at the University of Cambridge to work under the supervision of Ronald Norrish (winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1967), where it is said that "he had no success". According to his biographer, Norrish was "stubborn and almost perverse in argument, high-handed and sensitive to criticism". Norrish could not decide what Franklin would work on, and at such times he often drank heavily. Franklin wrote that for these reasons he utterly despised him. He resigned from Norrish's laboratory and complied with the requirements of the National Military Service Act, for which in 1942 he began work as an Assistant Research Officer with the British Association for Research. of Coal Use (BCURA), in Coombe Springs, near Kingston upon Thames, southwest of London. Norrish was serving as a military adviser at BCURA. John G. Bennett was the director. Marcello Pirani and Victor Goldschmidt, both Jewish refugees from the Nazis, were consultants and professors at BCURA when Franklin was attending. During his research at BCURA, he lived in Adrienne Weill's Cambridge boarding house until his cousin Irene Franklin told him she asked him to move with her into a vacant house belonging to her uncle in Putney. With Irene, she volunteered as an air raid warden and was in charge of organizing patrols to safeguard people's well-being during air raids.

He studied the porosity of carbon and compared the density of helium. He discovered the ratio between the fine constrictions in the coal pores and the permeability of the pore space. By concluding that substances were expelled in a pattern of molecular size, he helped classify coals and accurately predict their ability to be used as fuels and for the production of war devices (for example, gas masks). This work was the basis of his Ph.D. thesis, entitled The Physicochemistry of Solid Organic Colloids with Special Reference to Carbon, for which he received his degree in 1945. His work was the basis for several articles.

Paris

With the end of World War II in 1945, Franklin asked Adrienne Weill for help finding job openings for "a physical chemist who knows very little about physical chemistry and a lot about coal holes." In a lecture in the fall of 1946, Weill introduced it to Marcel Mathiu, director of the Center national de la recherche scientifique (National Center for Scientific Research), the network of institutes that make up most of the government-backed research laboratories. French. This led to an interview with Jacques Mering, at the State Chemical Services Central Laboratory in Paris. She joined Mering's team on February 14, 1947 as one of 15 researchers.

Mering was an X-ray crystallographer who applied X-ray diffraction to the study of rayon and other amorphous substances, in contrast to all the thousands of crystals that had been studied by this method for many years. taught the practical aspects of applying X-ray crystallography to amorphous substances. This presented new challenges in the development of experiments and in the interpretation of results. Franklin applied them to problems related to carbon, particularly the changes in the arrangement of atoms when it is converted to graphite, He published several other papers regarding this topic. This part of his work (which is described in a 1993 monograph, the annual, and in other publications) became the foundation of the field of coal physics and chemistry. Mering also continued the study of carbon in various ways, using X-ray diffraction and other methods.

King's College, London

In 1950, Franklin received a three-year Turner and Newall Fellowship to work at King's College, London. In January 1951, she began work as a research associate in the Medical Research Council (MRC) Biophysics Unit, headed by John Randall. Originally, she would work on X-ray diffraction applied to proteins and lipids in solution, but Randall she redirected her work to DNA fibers, thanks to recent developments in the field, as she was the only researcher with experimental diffraction experience at King's College at the time. Randall made this resignation, even before she she began her activities at King's, due to the subsequent pioneering work done by Maurice Wilkins and Raymond Gosling, a PhD student whom they assigned as her assistant.

With very little advanced equipment, Wilkins and Gosling were able to obtain an outstanding image of DNA through diffraction, which succeeded in arousing even more interest in the molecule. They had been working on DNA diffraction analysis in the unit since May 1950, but Randall did not disclose that he had asked Franklin to handle the DNA diffraction work and mentor Gosling for his thesis. Randall's lack of communication with regarding this assignment contributed significantly to the well-documented friction that was developing between Wilkins and Franklin.

Franklin, working with Gosling, began to apply his knowledge of X-rays to the structure of DNA. She used a microcamera and a new fine-focus X-ray tube, both ordered by Wilkins, which she carefully refined, adjusted, and focused. Using her training as a physical chemist, she carefully manipulated the critical hydration of her samples.When Wilkins inquired about these improved techniques, she replied in ways that offended Wilkins, as Franklin acted "with an air of quiet superiority." 3. 4;.

Franklin spoke concisely, directly, and impatiently while looking directly into her eyes, which made many of her colleagues nervous. Instead, Wilkins was very shy, premeditating his words, and avoiding direct eye contact. Despite the intense atmosphere, Franklin and Gosling discovered that there were two forms of DNA: when the humidity was high, the DNA fiber took on a shape long and thin, while in the dry state it acquired a short and wide shape.

These shapes were named A and B, respectively. Due to the intense conflict of personalities between Franklin and Wilkins, Randall divided the work on DNA. Franklin chose shape A, for which he had a vast database, while Wilkins selected shape B, since his preliminary discussions had suggested that it was helical. In addition, he showed great acumen in his evaluations of the preliminary data. The X-ray diffraction images taken by Franklin in those days were, in the words of J. D. Bernal, "some of the most beautiful X-ray photographs ever taken of a substance".

At the end of 1951, it was believed at King's College that the B form of DNA was helical, but after Franklin documented an asymmetric picture in May 1952, she herself no longer believed that the A form was helical. a helical structure. In July 1952, as a practical joke directed at Wilkins (who frequently stated that both forms of DNA were helical), Franklin and Gosling wrote a funeral notice lamenting the "death" of the crystal structure. helical DNA (A-DNA). During 1952, they applied the Patterson function to the DNA images they had generated. This was very demanding work, but it paid off and increased understanding of the structure of the molecule.

By January 1953, Franklin had reconciled his conflicting data and concluded that both forms of DNA were made up of 2 helices, and had begun writing a series of three manuscripts, two of which included a double-stranded DNA skeleton.. Her two manuscripts on form A were published in the journal Acta Crystallographica in Copenhagen on March 6, 1953, one day before Watson and Crick completed their model of B-DNA. sent while the Cambridge couple were building their model, and doubtless wrote them before learning of the content of their paper. to recent work by the King's and Cambridge task forces.[citation needed]

The third draft talked about the "B" of the DNA, dates from March 17, 1953 and was discovered years later by his colleague from Birkbeck, Aaron Klug, among other documents of his. Aaron later published an assessment of the close correlation between the draft and the third article in the original Nature trio of April 25, 1953. Klug designed this article to complement the first he had written, defending the significant contribution that Franklin made to the structure of DNA. He had written the first article in response to the incomplete representation of Franklin's work included in Watson's memoir The Double Helix, published in 1968.

On January 30, 1953, Watson traveled to King's College with a preliminary of the incorrect DNA structure proposal put forward by Linus Pauling. Since Wilkins was not in his office, Watson went to Franklin's lab with an urgent message that everyone should pitch in before Pauling realized his mistake. An unimpressed Franklin looked angry when Watson suggested that she didn't know how to interpret his data correctly. Watson hastily backed down and turned to Wilkins, who seemed drawn in by the commotion. Wilkins commiserated with his harassed friend, and they changed the course of DNA history: Wilkins unwisely showed Watson Gosling's X-ray diffraction image of DNA. Watson, for his part, showed Gosling Wilkins pre-publication of the Pauling and Corey manuscript. Photo 51 of Franklin and Gosling gave the Cambridge pair fundamental information about the structure of DNA, while the Pauling and Corey paper described a molecule remarkably similar to their first model, which was wrong.

The structure of DNA

In February 1953, Francis Crick and James D. Watson, of the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge University, had begun construction of a model of the B form of DNA using data similar to those obtained in King's College. Much of their data was derived from research done by Wilkins and Franklin. Franklin's research ended around February 1953, before he moved to Birkbeck, and his data proved critical. Modeling had been successfully applied by Linus Pauling in 1951 to elucidate the structure of the alpha helix, but Franklin was opposed to the premature creation of theoretical models until enough information had been collected to correctly guide modeling. Franklin also believed that building a model should only proceed until sufficient structural information is available.

Always cautiously, he sought to eliminate possibilities that would lead to erroneous conclusions. Photographers from Birkberck's team show that she used small molecular models routinely, though they certainly didn't match those used on a large scale at Cambridge for DNA. In mid-February 1953, Crick's thesis advisor, Max Perutz, provided Crick with a copy of the report written for a visit to King's by the biophysics committee of the medical research council in December 1952, which contained many crystallographic calculations made by Franklin.

Since Franklin had made the decision to transfer to Birkbeck College and Randall had decided that all DNA work should be kept at King's, Wilkins received copies of Franklin's photographs through Gosling. By February 28, 1953, Watson and Crick felt they had solved the problem, which was enough for Crick to proclaim (at a local bar) that they had "found the secret of life". However, they knew they had to. complete their model before they could be sure.

Watson and Crick finished building their model on March 7, 1953, the day before they received a letter from Wilkins, stating that Franklin was finally leaving, and that they could work without limitations. This was also a day later. that two articles by Franklin reached the Acta Crystallographica. Wilkins went to see the model the following week, according to Franklin biographer Brenda Maddox, on March 12; and supposedly to inform Gosling of his return to King's.

It is not certain how long it took for Gosling to inform Franklin, who was at Birkbeck, but his original manuscript of March 17 shows no indication that he knew of the Cambridge model. Franklin later modified this draft, before publishing it as the third of the trio of Nature articles. In response to receiving the preliminary manuscript from him, on March 18, Wilkins wrote: "They look to me like a couple of old rebels, but they may have gotten to something anyway."

Crick and Watson published their model in Nature on April 25, 1953 in an article describing the double helix structure of DNA, with a footnote acknowledging "felt stimulated by knowledge of the "unpublished" contributions of "Franklin and Wilkins". Even if it was only an elementary minimum, they had enough specific information obtained by Franklin and Gosling on which to base their model. As a result of a deal made by the two laboratory directors, the articles by Franklin and Wilkins, which included their X-ray diffraction data, were modified and published second and third in the same issue of Nature, which appeared to be only support for the theoretical paper by Watson and Crick proposing a model for the B form of DNA.

Weeks later, on April 10, Franklin wrote to Wilkins, requesting permission to see his model. Franklin maintained his skepticism about premature modeling even after seeing Watson and Crick's model and had little impressed. It is reported that she commented "It's very pretty, but how are they going to check it?" As an experimental scientist, Franklin seems to have been interested in producing much more relevant evidence, before publishing a proposed model at the time it was tested. Therefore, her response to the Watson and Crick model was to preserve her cautious way of doing science.Most of the scientific community was reluctant to accept the double helix model. Initially, many geneticists accepted the model because of its obvious genetic implications.

Birkbeck College

Franklin left King's College, London in mid-March 1954, for Birkbeck College, on a transfer she had planned for some time, which she described (in a letter to Adrienne Weill in Paris) like "moving from a palace to the slums... but nicer at the same time". She was recruited by physics department head J. D. Bernal, a brilliant crystallographer who happened to be an Irish communist, known for promoting women crystallographers.. Franklin worked as a senior scientist with her own research group, funded by the Agricultural Research Council. Despite Bernal's last words (on being fired) to stop his interest in nucleic acids, she helped Gosling finish his thesis, even though she was no longer its official supervisor. Together they published the first evidence of double helixes in the A form of DNA in the July 1953 issue of Nature. In addition, they continued to explore another of the most important nucleic acids, RNA, a similar molecule crucial to life than DNA. She again used X-ray crystallography to study the structure of the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), an RNA virus. Her meeting with Aaron Klug in early 1954 sparked a long and successful working relationship. Klug had just received his PhD from Trinity College, Cambridge, and had joined Birkbeck in late 1953. In 1955 Franklin published the first of his major papers on TMV in Nature, in the which described all TMV virus particles as having the same length. This contradicted the ideas of the eminent virologist Norman Pirie, although she was ultimately correct.

Franklin assigned the study of the entire TMV structure to his doctoral student, Kenneth Holmes. They soon discovered that the TMV coat was proteins arranged in the form of a helix. His colleague Klug worked on spherical viruses with his student John Finch, with Franklin coordinating and supervising the work. As a team, from 1956, they began to publish highly influential studies. about TMV, Cucumber virus 4 and Turnip yellow mosaic virus.

Franklin also had a research assistant, James Watt, subsidized by the National Coal Board; at the time, she was also the leader of Birkbeck's ARC group. Members of Birkbeck's team continued with RNA viruses that affect many plants, including potatoes, turnips, tomatoes, and peas. In 1955, an American postdoctoral student named Donald Caspar joined the team. He focused on the precise localization of RNA molecules in the TMV. In 1956, he and Franklin published separate but complementary papers in a March issue of Nature, showing that the RNA in TMV is bound to the inner surface of the hollow virus. Caspar was not a keen writer, to the point that Franklin had to write the entire manuscript for him.

In 1957, his ARC-provided research grant expired; however, he was granted a one-year extension, so that it would end in March 1958. Thanks to this, he applied for a new scholarship to the National Institute of Health of the United States, which was approved providing 10,000 pounds for three years, the largest fund ever received at Birkbeck.

The first international event after World War II, called Expo 58, would take place in Brussels in 1958. An invitation was extended to Franklin to make a 5-foot-tall TMV model, which began in 1957. His materials were ping pong balls and plastic bicycle handlebar grips. The Brussels World's Fair, which featured an exhibit of his model of the virus in the International Science Pavilion, opened on April 17, just the day after his death.

His main research team at Birkbeck College, London, Klug, Finch and Holmes moved to the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge in 1962.Personal life

Franklin described herself as an agnostic. Her lack of religious faith apparently stemmed not from any outside influence, but from her own inquisitive mind. Since she was little, she developed a skeptical attitude. Her mother recalled that, when opposed to believing in the existence of God, Rosalind said, "Well, how do you know He isn't She anyway?" She later qualified her opinion based on her scientific experience, and wrote to his father in 1940:

Science and daily life cannot and should not be separated. Science, for me, gives a partial explanation of life... I do not accept your definition of faith, that is, in life after death.... Your faith is based on your future and that of others as individuals; mine, my future and my successors. I think yours is more selfish... Referring to the question of a Creator. Creator of what? I see no reason to believe that the creator of protoplasm or of primary matter has any reason to feel interest in our insignificant race in a small corner of the universe.

Though, on the other hand, he never abandoned Jewish traditions. As the only Jewish student at Lindores School, she took Hebrew lessons on her own while her friends went to church. She joined the Jewish Society at 27, out of respect for her grandfather's request. Franklin she confided to her sister that she "was always a conscientious Jew".

Franklin loved to travel abroad, particularly hiking. She "first qualified at Christmas 1929" for a holiday in Menton, France, where her grandfather was sheltering from the English winter.Her family frequently holidayed in Wales or Cornwall. A trip to France in 1938 generated in her a lasting love for the country and its language. He regarded the French way of life as "far superior to the English way of life". In contrast, he described the English as people who "possessed vacant, stupid faces and a childish complacency". His family was almost trapped in Norway in 1939., as World War II started while they were on their way home. On another occasion, in 1946, he took an excursion to the French Alps with Jean Kerslake that almost cost him his life. She slipped on a slope and was barely rescued.] she Nevertheless, she wrote to her mother: “I am sure she could happily hang around in France forever. I love the people, the country and the food."

He made several professional trips to the United States and was especially jovial with his American friends, constantly displaying a good sense of humor. William Gonza, of the University of California, Los Angeles, commented that she was the perfect opposite of Watson's description of her, and Maddox commented that Americans enjoyed her "lighthearted side of her" about her.

Watson, in The Double Helix, refers to Franklin as "Rosy" most of the time, the nickname that the people of King's College used behind her back, she did not like to be called that, because she had a great-aunt Rosy. Within her family she was called "Ros" For others, she responded to Rosalind. This she made clear to a visiting American friend, Dorothea Raacke, as they sat at Crick's table in The Eagle bar. Raacke asked her what she should call her, to which she replied, "Rosy, I'm afraid," adding, "Definitely not Rosy."

He frequently expressed his political views. He initially blamed Winston Churchill for promoting the possibility of war, but later admired him for his speeches. He actively supported John Alfred Ryle, Regents Professor of Physics at Cambridge University, as an independent candidate for Member of Parliament in 1940, to no avail.

She didn't seem to be intimate with anyone and kept her deepest feelings to herself. Since her childhood she avoided close friendships with the opposite sex. One time when her cousins visited, she paid Roland to accompany them. Years later, Evi Ellis, who was then married to Ernst Wohlgemuth, had moved to Notting Hill from Chicago and tried to get him to start a relationship. with Ralph Miliband, but failed. Franklin told Evi that his roommate wanted to buy her a drink, but she did not understand his intentions. She was hopelessly in love with her French mentor Mering, who had a wife and a mistress. Mering also admitted that his "intelligence and beauty" captivated him. According to Sayre, she confessed her feelings for Mering while undergoing surgery, but her family denied this. Mering wept when he later visited her, and destroyed all of her letters.

His closest personal relationship was probably with his post-doc student, Donald Caspar. In 1956, she visited him at her home in Colorado, after going on a trip to the University of California, Berkeley, and Franklin is reported to have commented that Caspar "was someone she could have loved, even married." ». In her letter to Sayre, she described him as "an ideal match."

Illness and death

In mid-1956, during a business trip to the United States, Franklin began to suspect that he had a health problem. In New York, she couldn't deny the fact that his stomach was swollen. Returning to London, she consulted Mair Livingstone, who told her, "You're not pregnant," to which she replied, "I wish I was." Her diagnosis revealed that she was not pregnant, and her case was marked "urgent". An operation on September 4 of the same year revealed tumors in her abdomen. After this period of hospitalization, Franklin spent time convalescing with various friends and relatives, such as Anne Sayre, Francis Crick and his wife Odile, with whom Franklin already had a great friendship; and with the family of Roland and Nina Franklin, being Rosalind's nephews who helped him feel better.

Franklin decided not to stay with her parents, because her mother's grief and crying upset her too much. Even while he was undergoing treatment for cancer, Franklin and his group continued to work and generate results: seven articles in 1956 and six more in 1957. In 1957, the group was also working on the polio virus, and thanks to these publications it obtained funds from the Public Health Service and the National Institutes of Health in the United States.

In late 1957, Franklin fell ill again and was admitted to the Royal Marsden Hospital. On December 2 she wrote her will. She designated her three brothers as executors and Aaron Klug as her primary beneficiary, who would receive £3,000 and her Austin car from her. Her other friends would get: Mair Livingstone, £2,000; Anne Piper, £1000, and her nurse, Miss Griffith, £250. The remaining amount would be used for charity. She returned to work in January 1958, and was appointed Biophysical Research Associate on February 25. She relapsed on March 30, and died of bronchopneumonia on April 16, 1958. secondary carcinomatosis and ovarian cancer in Chelsea, London. Exposure to X-rays may have been one of the risk factors, in addition to genetic predisposition.

Other members of her family died of cancer, and the incidence of gynecological cancer is known to be particularly high among Ashkenazi Jews. Her death certificate reads: "Research scientist, single, daughter of Ellis Arthur Franklin, banker." She was buried on 17 April 1958 in a family section in the Willesden Synagogue Jewish Cemetery, in the London Borough of Brent, with the following epitaph:

IN MEMORY

ROSALIND ELSIE FRANKLIN

أعربي من مع من من من من من من من من من من م م من من من

WOMAN:

ELLIS AND MURIEL FRANKLIN

25 JULY 1920 - 16 APRIL 1958

SCIENTIFIC

INVESTIGATION AND ITS DISCUSSIONS IN MATERIA

_

FOR HUMANITY

Initiales in Hebrew that indicate: "Your soul will remain in the making of life." ]

Posthumous controversies

Various controversies have arisen since Franklin's death:

Allegations of sexism

Sayre, one of Franklin's biographers, stated: "In 1951...King's College as an institution was not distinguished by its welcoming of women...Rosalind...was not used to to purdah (a religious and social form of female exclusion)... there was only one other female scientist on the lab staff." Andrzej Stasiak states: "Sayre's book is continually quoted in feminist circles, to expose strong sexism in the field of sciences". Farooq Hussain states: "there were 7 women in the biophysics department...Jean Hanson became one of them, the Maid of Honor B. Fell, director of the Strangeways Laboratory, supervised the biologists'. Maddox notes, "Randall...had many women on his staff...they found him...empathetic and helpful.".

Sayre argues, "While the male employees at Kings ate lunch in a large, comfortable, club-like dining room," female members of various ranks "ate in the student lobby or away from the immediate vicinity of the building." Elkin states that most of the CIM group usually ate together (including Franklin) in the joint diner mentioned below. Maddox states of Randall: "He liked to see his people, men and women, get together for morning coffee and at lunch in the mixed canteen, where he ate almost every day". Francis Crick also commented that "his colleagues treated men and women scientists alike".

Sayre also argues about Franklin's struggle to follow the path of science and her father's concern about women getting academic positions. This statement has been used as the basis for charging Ellis Franklin of sexism against his daughter. A significant amount of information explicitly states that he was opposed to her entering Newnham College. The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) biography even states that he refused to pay her fees, and that an aunt had to support her. Her sister Jenifer Glynn explains that these stories are myths and that Franklin's parents paid for her entire career.

The Double Helix, James Watson's memoir published 10 years after Franklin's death and Watson's return from Cambridge to Harvard, is said to be steeped in sexism. His colleague of Cambridge, Peter Pauling, wrote in a letter: "Wilkins is supposed to be doing this job. Miss Franklin is obviously a fool.” Crick acknowledges after her, “I'm afraid we tended to take, shall we say, a patronizing attitude toward her.”

Glynn accuses Sayre of turning his sister into a feminist heroine, and Watson's The Double Helix as the root of what he calls "the Rosalind industry". She surmises that these alleged stories of sexism "would have embarrassed her almost as much as she would have been annoyed by Watson's testimony," and stated that "she was never a feminist." Klug and Crick also agreed that she was definitely not a feminist.

A letter from Franklin to her family in January 1939 is taken as demonstrating her own prejudiced attitude and the fact that "she was not immune to the terrible sexism in those circles." In the letter, she said that a professor was “very good, but a woman.” But Maddox explains that it was more of a circumstantial comment than gender bias. In fact, she laughed at men who were embarrassed by the appointment of the first female professor, Dorothy Garrod.

Contributions to the DNA model

The first major contribution to the Watson and Crick model was his lecture at the seminar in November 1951, where he introduced to those present, including Watson, the two forms of the molecule, A and B, and the claim that phosphate units are located on the outside of the molecule. In addition, he specified the amount of water found in the molecule according to other parts of the molecule, data that is of considerable importance in terms of molecular stability. Franklin was the first to describe and formulate these facts, which actually formed the basis for all other attempts to model this molecule. However Watson, at the time ignorant of the relevant chemistry, failed to understand the crucial information, leading to the construction of the wrong model.

The other contribution includes an X-ray photograph of B-DNA, (called photograph 51), which Wilkins briefly showed Watson in January 1953, and a written report for a visit by the ICJ biophysics committee to King's College in December 1952. Perutz, Crick's thesis supervisor and member of the ICJ visiting committee, gave this report to Crick, who was working on his thesis on the structure of hemoglobin at the time.

Sayre's biography of Franklin contains a story stating that Wilkins showed photograph 51 to Watson without Franklin's permission, and that this is an example of scientific misconduct. Others reject this claim. theory, and they assure that Watson had received this photograph through Gosling, Franklin's doctoral student because she was already leaving King's College to work at Birkbeck, and that there was nothing negative about it, well Principal Randall insisted that all work on DNA belonged exclusively to King's College and that he had even ordered Franklin, through a letter, to stop working on the molecule and submit his information. Horace Freeland Judson implied that Maurice Wilkins took the photograph of Franklin's drawer, but this too is said to be incorrect.

Similarly, Perutz "did not consider it harmful" to show Crick the ICJ report containing Franklin and Gosling's conclusions about their analyzes of their X-ray data, because it had not been marked confidential, although it was "not predestined to be seen by outsiders". After the publication of Watson's The Double Helix exposed Perutz's actions, he received so many letters judging his judgment that he felt the need to answering all of them, and revealing a general statement in Science apologizing for being "inexperienced in administrative matters".

Perutz also stated that the ICJ information was already available to the Cambridge team when Watson had attended the seminar in November 1951. Much of the material contained in the December 1952 ICJ report had been pre-released. had been introduced by Franklin in a talk he had given in November 1951, which Watson attended but did not understand.

Perutz's letter was one of 3 letters published along with others from Wilkins and Watson, arguing about their various contributions. Watson clarified the importance of the data obtained from the ICJ report since he had not captured this information when he attended Franklin's lectureship in 1951. The culmination of all this came when Crick and Watson began creating their model in February 1953 and were working with critical parameters that had been determined by Franklin in 1951 and had been significantly refined by her and Gosling in 1952, along with their published data and others very similar to those available at King's. It was widely believed that Franklin was never aware that her studies had been used during the construction of the model, but Gosling said in a 2013 interview: “Yes. She knew about it."

Acknowledgment of his contributions to the DNA model

After the model was completed, Crick and Watson invited Wilkins to co-author the paper describing the structure. Wilkins declined the offer, as he had not been involved in its construction. He later expressed regret that he did not there would have been more discussion about the co-author, as this might have helped clarify how much King's College contributed to the discovery. There is no doubt that Franklin's experimental information was used by Watson and Crick to build their model of DNA in 1953. Some, including Maddox, who is quoted in the following paragraphs, have explained this omission in citations as a matter of citations, as it would have been very difficult to cite the unpublished results of the ICJ report they had seen.

A one-off reconnaissance would have been difficult to handle, due to the way data was transferred from King's College to Cambridge. However, there were methods available. Watson and Crick could have cited the ICJ report as a personal communication and could have cited the articles with edit status of the Minutes or, even easier, the third article of Nature who also knew it was in editing status. One of the most important achievements of Maddox's acclaimed biography is that the author presented a well-received case of inadequate acknowledgment. The recognition given to him was very subdued and always paired with the Wilkins name.

Twenty-five years after the event, the first clear citations to Franklin's contributions appear in The Double Helix, as Watson's testimony was permeated, although these are buried under descriptions (which in various cases are very negative) of Franklin during his period of work on DNA. This attitude reaches its climax in the confrontation between Watson and Franklin over a previous printing of Pauling's erroneous manuscript on DNA. Franklin's words motivated Sayte to write his rebuttal, in chapter 9 of which, entitled & #34;Winner Take All", is the structure of a legal summary that describes and analyzes the issue of recognition.

Sayre's initial analysis is often ignored due to the feminist undertones that can be perceived in her book.[citation needed] In the original article, Watson and Crick did not cite Wilkins' or Franklin's X-ray work. In any case, they admit to having been stimulated by the general knowledge of the nature of the experimental results and "unpublished" ideas of Dr. M. H. F. Wilkins and Dr. R. E. Franklin and their colleagues at King's. College London. Watson and Crick had no experimental data to support their model. It was Franklin and Gosling's publication in the same issue of Nature, with the X-ray image of DNA serving as the main evidence, in which they concluded:

Therefore, our ideas are not inconsistent with the model proposed by Watson and Crick in the preceding sections.

Nobel Prize

Franklin was never nominated for a Nobel Prize. She died in 1958, and during her lifetime the structure of DNA was not considered fully proven. It took Wilkins and her colleagues about seven years to collect enough information to test and refine the proposed structure of DNA. Furthermore, its biological importance, proposed by Watson and Crick, had not been determined. General acceptance for the DNA double helix and its function was not determined until the late 1950s, leading to nominations for the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 1960, 1961, and 1962, and in 1962 for the Nobel Prize. Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The first notorious event in this regard was made by Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl in 1958, who experimentally showed the DNA replication of the bacterium Escherichia coli . Through from the Meselson-Stahl experiment, it was shown how DNA replicates to form two helices of two strands each, and each of these helices carries one of the original strands of DNA. This concept of DNA replication became firmly established around 1961 after its demonstration in other species and stepwise chemical reaction. According to Crick and Monod's 1961 letter, this experimental proof and initiation of the diffraction work on DNA started by Wilkins were the reasons why it seemed to Crick that Wilkins should have been included in the Nobel Prize for DNA.

In 1962, Crick, Watson, and Wilkins received the Nobel Prize. It is unclear whether Franklin should have been included, had she been alive. The prize was awarded for her entire work and not specifically for her work. the discovery of the double helix. When the prize was awarded, Wilkins had been studying the structure of DNA for more than 10 years and had contributed significantly to confirming the Watson and Crick model. Crick had worked on the genetic code at Cambridge, and Watson at RNA for some years. Watson has suggested that ideally, Wilkins and Franklin should have won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

It is also interesting that Franklin's colleague and main beneficiary of his will, Klug, was the sole winner of the Chemistry prize in 1982, "for his development of crystallographic electron microscopy and his structural elucidation of nucleic acid- biologically important protein". This work was exactly what Franklin had started and which he presented to Klug. It is highly plausible that, if she had been alive, she would have shared the Nobel with him.

Poshumous awards

- 1982, Iota Sigma Pi appointed Franklin as a National Honorary Member.

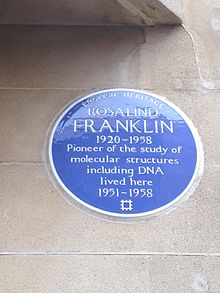

- 1992, English Heritage (English Patrimony) placed a blue plaque on the entrance wall of SW10, Drayton Gardens, 107, Donovan Court, where Rosalind Franklin lived during his career until his death. The inscription says "Rosalind Franklin, 1920-1958, pioneer in the study of molecular structures, including DNA, lived here in 1951-1958."

- 1993, King's College London renamed the Orchard Residence as Rosalind Franklin Hall on its Hampstead campus at Kidderpore Avenue.

- 1993, King's College London placed a blue plaque on its outer wall, with the inscription: "R. E. Franklin, R. G. Gosling, A. R. Stokes, M. H. F. Wilkins, H. R. Wilson King's College London/DNA Studies with X-ray diffraction 1953."

- 1995, Newnham College opened a residence for graduate students, called the Rosalind Franklin Building, and placed a bust of his in his garden.

- 1997, the Birkbeck Crystal School, University of London, opened the Rosalind Franklin Laboratory.

- 1997, the asteroid discovered in 1997 was named (9241) Rosfranklin.

- 1998, the National Portrait Gallery in London added the portrait of Rosalind Franklin along with those of Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins.

- 1999, the Institute of Physics in Portland Place, London, renamed its theater as the Franklin Theater.

- 2000, King's College London created the Franklin-Wilkins Building in honor of the work of both at the university. In 1994, King's College had called one of the halls at the Hampstead Campus residences in memory of Rosalind Franklin.

- 2001, the U.S. National Cancer Institute created the Rosalind E. Franklin Award for Women in Cancer Research.

- 2003, the Royal London Society created the Rosalind Franklin Award for outstanding contributions in any area of natural science, engineering or technology.

- 2003, the Royal Chemistry Society declared the King's College of London as a "National History of Chemistry" and placed a plaque on the wall near the entrance of the building, with the epitaph: "Cerca of this site Rosalind Franklin, Maurice Wilkins, Raymond Gosling, Alexander Stokes and Helbert Wilson carried out experiments that led to the discovery of the DNA structure. These studies revolutionized our understanding of chemistry behind life itself."

- 2004, the University of Finch of Health Sciences/the Chicago Medical School, located in North Chicago, Illinois changed its name to the University of Medicine and Rosalind Franklin Sciences. He also adopted the new motto "Life at Discovery", and began using photography 51 as his logo.

- 2005, the inscription in DNA sculpture (which was donated by James Watson) located outside Clare College, Cambrige Memorial Patio says: (a) at the base: (i) "These strings unravel during cell reproduction. Genes are encoded in the sequence of the bases." and (ii) "The double propeller model was supported by the work of Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins", as well as (b) In the propellers: (i) "The structure of DNA was discovered in 1953 by Francis Crick and James Watson as they lived here in Claire", and (ii) "The DNA molecule has two helical chains that are joined by the adenine-timin or guanine-cytosine base pairs."

- 2006, the Rosalind Franklin Society was founded in New York, which aims to recognize, encourage and promote the contributions of important women in the life sciences and affiliated disciplines.

- 2007, the University of Groningen, supported by the European Union, launched the Rosalind Franklin Fellowship Programme to encourage researchers to become full-time university professors.

- 2008, Columbia University awarded a Lousia Gross Horwitz honorary award to Rosalind Franklin, Ph.D., "for its fundamental contributions to the discovery and structure of DNA."

- The St Paul's School for Girls founded the Rosalind Franklin Technology Center.

- 2012, a similar online project was named to Rosalind, which teaches programming via molecular biology.

- 2012, Professor Lord Robert Winston opened at the University of Nottingham Trent the research building Rosalind Franklin, which was a multi-million dollar project.

- 2013, Google honored Rosalind Franklin with a doodle In which you can be seen by observing the double propeller structure of DNA in front of Photography 51.

- March 7, 2013, a plaque was placed on the wall of The Eagle, a pub near the University of Cambridge where Watson and Crick announced the discovery of the DNA structure 60 years ago.

- 2014, the BIO Rosalind Franklin Award was established by the Organization of Biotechnology Industry, in collaboration with the Rosalind Franklin Society, for outstanding women in the field of industrial biotechnology and bioprocesses.

- 2014, the University of Medicine and Sciences Rosalind Franklin revealed a bronze statue of Franklin, created by Julie Rotblatt-Amrany, near its front entrance. Franklin's nephew, Martin Franklin, and his niece Rosalind Franklin Jekowsky came to the ceremony on May 29.

- 2019, you are assigned the name Rosalind Franklin to the rover of the Russian-European mission to Mars ExoMars.

Cultural references

- Franklin's role in the discovery of the nature of DNA is the theme of the TV movie Life Storystarring Tim Pigott-Smith as Crick, Alan Howard as Wilkins, Jeff Goldblum as Watson and Juliet Stevenson as Franklin.

- PBS NOVA transmitted in 2003 a 56-minute documentary on Franklin's life and scientific contributions, entitled DNA - The Secret of Photography 51. The program contains interviews with Wilkins, Gosling, Klug, Maddox and is narrated by Barbara Flynn. It also includes interviews with Vittorio Luzzati, Caspar Anne Piper and Sue Richley, all of them Franklin's friends. The UK version produced by the BBC is incorporated Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA.

- The first episode of a PBS documentary series, DNA, aired on January 4, 2004. The episode entitled The Secret of Life focuses mainly on Franklin's contributions. The documentary is narrated by Jeff Goldblum, and presents contents in which Watson, Wilkins, Gosling and Peter Pauling (son of Linus Pauling) are involved.

- Deborah Gearing wrote the play Rosalind: A Life Question, about Franklin's work, presented for the first time on November 1, 2005 at the Birmingham Repertoire Theatre and published by Oberon Books in 2006.

- Photograph 51, written by the American playwright Anna Ziegler, was published in 2011. It has been presented in the United States and in 2015 will be premiered at the Noel Coward Theatre of the West End of London. Ziegler's version of the 1951-53 "carrier" regarding the structure of DNA emphasizes the key role of Franklin's research and personality. Although it sometimes alters history to create a dramatic effect, the work does not fail to clarify several of the key issues about how science takes place.

- Fake assumptions, by Lawrence Aronovitch, is a work about the life of Marie Curie in which Franklin is described as frustrated and angry at the lack of recognition of his scientific research.

Posts

Rosalind Franklin spawned several publications, some of which have been cited multiple times. A representative list appears below. The last two were posthumous.

- Bangham, D. H. and Rosalind E. Franklin (1946), «Thermal expansion of coals and carbonised coals», Transactions of the Faraday Society 48: 289-295, doi:10.1039/TF946420B289, consulted on 14 January 2011from The Rosalind Franklin Papers, in "Profiles in Science", in National Library of Medicine

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1949), «A study of the fine structure of carbonaceous solids by measurements of true and apparent densities: Part 1. Coals, Transactions of the Faraday Society 45 (3): 274-286, doi:10.1039/TF94500274, consulted on 14 January 2011By the National Library of Medicine above. Date count 88

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1949), «A study of the fine structure of carbonaceous solids by measurements of true and apparent densities: Part 2. Carbonized coals”, Transactions of the Faraday Society 45 (7): 668-682, doi:10.1039/TF94500668, consulted on 14 January 2011Per National Library of Medicine above. Date count 49

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1949), "Note sur la estructura colloidale des houilles carbonisees", Bulletin de la societe chimique de France 16 (1,2): D53-D54 Appointment count 0

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1950), “On the structure of carbon”, Journal de Chimie Physique et de Physico-Chimie Biologique 47 (5.6): 573-575, consulted on 14 January 2011By the National Library of Medicine above. Date count 16. Note: This journal stopped publishing in 1999

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1950), «A rapid approximate method for correcting the low-angle scattering measurements for the influence of the finite height of the X-ray beam», Acta Crystallographica 3 (2): 158-159, doi:10.1107/S0365110X50000343Date count 15

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1950), "The interpretation of diffuse X-ray diagrams of carbon", Acta Crystallographica 3 (2): 107-121, doi:10.1107/S0365110X50000264245. (In this article Franklin quotes Moffitt)

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1950), «Influence of the bonding electrons on the scattering of X-rays by carbon», Nature 165 (4185): 71-72, Bibcode:1950Natur.165...71F, PMID 15403103, doi:10.1038/165071a0Date count 11

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1951), «Les carbones graphitisables et non-graphitisables», Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences, Submitted by G. Rimbaud, session of 3 January 1951 232 (3): 232-234 Appointment Count 7

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1951), "The structure of graphitic carbons", Acta Crystallographica 4 (3): 253-261, doi:10.1107/S0365110X51000842Date count 398

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Bacon, G. E. and R. E. Franklin (1951), “The alpha dimension of graphite”, Acta Crystallographica 4 (6): 561-562, doi:10.1107/s0365110x51001793Date count 8

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1951), «Crystallite growth in graphitizing and non-graphitizing carbons», Proceedings of the Royal Society A 209 (1097): 196-218, Bibcode:1951RSPSA.209..196F, doi:10.1098/rspa.1951.0197Appointment count 513. Available for free on the doi site or alternatively on The Rosalind Franklin Papers Collection of the National Library of Medicine

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1953), «Graphitizing and non-graphitizing carbons, their formation, structure and properties», Angewandte Chemie 65 (13): 353-353, doi:10.1002/ange.19530651311Date count 0

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1953), «The role of water in the structure of graphitic acid», Journal de Chimie Physique et de Physico-Chimie Biologique 50: C26

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E. (1953), «Graphitizing and nongraphihastizing carbon compounds. Formation, structure and characteristics”, Brenstoff-Chemie 34: 359-361

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - R. E. Franklin and R. G. Gosling (25 April 1953), "Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate", Nature 171 (4356): 740-741, Bibcode:1953Natur.171..740F, PMID 13054694, doi:10.1038/171740a0, consulted on 15 January 2011Reprint also available in Resonance Classics

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, R. E.; Gosling, R. G. (1953). «The structure of sodium thymonucleate fibres. I. The influence of water content». Acta Crystallographica 6 (8): 673-677. doi:10.1107/S0365110X53001939.

- Franklin, R. E.; Gosling, R. G. (1953). «The structure of sodium thymonucleate fibres. II. The cylindrically symmetrical Patterson function». Acta Crystallographica 6 (8): 678-685. doi:10.1107/S0365110X53001940.

- Franklin, R. E. and M. Mering (1954), "The structure of l'acide graphitique", Acta Crystallographica 7 (10): 661-661, doi:10.1107/s0365110x54002137

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, Rosalind and K. C. Holmes. (1956), «The Helical Arrangement of the Protein Sub-Units in Tobacco Mosaic Virus», Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 21: 405-406, PMID 13363941, doi:10.1016/0006-3002(56)90043-9, consulted on 14 January 2011Access to the article by the National Library of Medicine above

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, Rosalind E. and A. Klug (1956), «The nature of the helical groove on the tobacco mosaic virus particle X-ray diffraction studies», Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 19 (3): 403-416, PMID 13315300, doi:10.1016/0006-3002(56)90463-2

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Klug, Aaron, J. T. Finch and Rosalind Franklin (1957), "The Structure of Turnip Yellow Mosaic Virus: X-Ray Diffraction Studies", Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 25 (2): 242-252, PMID 13471561, doi:10.1016/0006-3002(57)90465-1, consulted on 14 January 2011By the National Library of Medicine

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, Rosalind, Aaron Klug, J. T. Finch and K. C. Holmes (1958), «On the Structure of Some Ribonucleoprotein Particles», Discussions of the Faraday Society 25: 197-198 doi:10.1039/DF9582500197, consulted on 14 January 2011By the National Library of Medicine

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Klug, Aaron and Rosalind Franklin (1958), «Order-Disorder Transitions in Structures Containing Helical Molecules», Discussions of the Faraday Society 25: 104-110, doi:10.1039/DF9582500104, consulted on 14 January 2011By the National Library of Medicine

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Klug, Aaron, Rosalind Franklin S. P. F. Humphreys-Owen (1959), «The Crystal Structure of Tipula Iridescent Virus as Determined by Bragg Reflection of Visible Light», Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 32 (1): 203-219, PMID 13628733, doi:10.1016/0006-3002(59)90570-0, consulted on 14 January 2011By the National Library of Medicine

|obra=and|publicación=redundant (aid). - Franklin, Rosalind, Donald L. D. Caspar and Aaron Klug (1959), «Chapter XL: The Structure of Viruses as Determined by X-Ray Diffraction», Plant Pathology: Problems and Progress, 1908–1958, University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 447-461, consulted on 14 January 2011By the National Library of Medicine.

Complementary bibliography

- Brown, Andrew (2007). J. D. Bernal: The Sage of Science. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-920565-5.

- Chomet, Seweryn [Ed.] (1995). D.N.A.: Genesis of a Aiscovery. England: Newman-Hemisphere. ISBN 978-1-56700-138-9.

- Crick, Francis (1988). What Mad Pursuit: A Personal View of Scientific Discovery. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-09138-5.

- Dickerson, Richard E. (2005). Present at the Flood: How Structural Molecular Biology Came about. Sunderland: Sinauer. ISBN 0-87893-168-6.

- Finch, John (2008). A Nobel Fellow on Every Floor: A History of the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology. Cambridge: Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology. ISBN 978-1-84046-940-0.

- Gibbons, Michelle G. (2012). «Reassessing Discovery: Rosalind Franklin, Scientific Visualization, and the Structure of DNA». Philosophy of Science 79: 63-80. doi:10.1086/663241.

- Hager, Thomas (1995). Force of Nature: The Life of Linus Pauling. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80909-5.

- Horace, Freeland Judson (1996) [1977]. The Eighth Day of Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Biology (highly edited). Plainview, N.Y.: CSHL Press. ISBN 0-87969-478-5.

- Glynn, Jenifer (1996). "Rosalind Franklin, 1920-1958". Shils, Edward, ed. Cambridge Women: Twelve Portraits. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 267-282. ISBN 0-521-48287-9.

- Klug, Aaron (2004). "R.E. Franklin." In Matthew, H.C.G.; Harrison, Brian, eds. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: From the Earliest Times to the Year 2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-861411-X.

- Klug, Aaron (2004). «The discovery of the DNA Double Helix». In Krude, Torsten, ed. DNA: Changing Science and Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 5-27. ISBN 0-52182-378-1.

- Olby, Robert (1974). "Rosalind Elsie Franklin". In Gillispie, Charles Coulston, ed. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. V.10. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-10121-1.

- Olby, Robert (1994). The Path to The Double Helix: The Discovery of DNA (Complete, corrected and increased Dover edition). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-68117-3.♪

- Olby R. (16 January 2003). «Quiet debut for the double helix». Nature 421 (6921): 402-405. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..402O. PMID 12540907. doi:10.1038/nature01397.

- Santesmases, María Jesús Santesmases; Calvo Roy, Antonio (2019). Rosalind Franklin. PRISA. ISBN 978-84-9907-117-6.

- Tait, Sylvia A. S.; Tait, James F. (2004). A Quartet of Unlikely Discoveries. London: Athena Press. ISBN 978-1-8440-1343-2.

- Wilkins, Maurice (2005). The Third Man of the Double Helix: The Autobiography of Maurice Wilkins. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280667-3.

Contenido relacionado

Compsognathus longipes

Organometallic chemistry

Protostomy