Romance languages

The Romance languages (also called Romance languages, Latin languages, or Neolatin languages) are a branch of Indo-European of languages closely related to each other and that historically appeared as an evolution (or equivalent) of Vulgar Latin (understood in its etymological sense of everyday speech of the vulgar or common people) and opposed to Classical Latin (a standardized form that from a certain moment it was a language learned as a second language and not as a mother tongue).

They were the Italic languages that survived through the Roman Empire, becoming extinct the twin language of Latin (the Faliscan) and also disappearing an Italic group parallel to the Latino-Faliscans, like the Osco-Umbras.

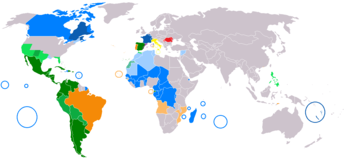

The six most widely spoken Romance languages by total number of speakers are Spanish (489 million), [citation required] Portuguese (283 million), [citation needed] French (77 million), [citation needed] Italian (67 million), [citation required] Romanian (24 million) [citation required] and Catalan (10 million). However, the number of known Romance languages exceeds twenty, although today many regional varieties are seriously threatened and only half a dozen of them are in general use and several million speakers.

Location and history: Romania

These languages were and are still spoken in a territory called Romania, which covers most of the southern Europe of the ancient Roman Empire. The terms romance and Romania actually come from the adverb romanice, "in Roman", from the Latin adjective romanicus : Its speakers were considered to be using a language borrowed from the Romans, as opposed to other languages present in the territories of the old Empire, such as Frankish in France, the language of the Franks belonging to the family of Germanic languages. Well, romanice loqui, "to speak in Roman" (that is, the vernacular Latin dialect) is in contrast to latine loqui, "to speak in Latin" (Medieval Latin, the conservative version of the language used in formal scripts and contexts or as a lingua franca), and with barbarice loqui, "to speak barbarian" (the non-Latin languages of the peoples outside the Roman Empire).

The first writing in which the term Roman is found, in one way or another, dates back to the synod of Tours in the year 813. It is from that synod that it is considered that the first language Vulgar is separated from Latin, and is in effect designated as a separate language. It is a form of Proto-French known as romana lingua or román. However, in the Cartularios de Valpuesta, there is an earlier text dating from the year 804, and it is written in highly Romanized Latin.

The evolution of Vulgar Latin towards Romance languages is dated, grosso modo, as follows:

- Between 200 B.C. and 400 approximately: different forms of vulgar Latin.

- Between 500 and 600: these forms begin to distinguish one another.

- From 800: the existence of romance languages is recognized.

Romance languages by number of speakers

| Pos. | Language | Native speakers [chuckles]required] | Total speakers [chuckles]required] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spanish | 496 000 | 596 000 | |||||||||||

| 2 | French | 93 000 | 321 000 | |||||||||||

| 3 | Portuguese | 250 000 | 273 000 | |||||||||||

| 4 | Italian | 64 000 | 85 000 | |||||||||||

| 5 | Romanian | 23 600 000 | 27 600 000 | |||||||||||

| 6 | Catalan/valencian | 4 980 600 | 10 048 969 | |||||||||||

| 7 | Haitian criollo | 13 000 | ||||||||||||

| 8 | Sicilian | 4 700 000 | ||||||||||||

| 9 | emiliano-romañol | 4 400 000 | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Galician | 2 936 527 | 3 900 000 | |||||||||||

| 11 | véneto | 3 800 000 | ||||||||||||

| 12 | Lombard | 3 600 000 | ||||||||||||

| 13 | Neapolitan | 3 000 000 | ||||||||||||

| 14 | piamontés | 700 000 | 1 600 000 | |||||||||||

| 15 | Sardinian | 1 350 000 | ||||||||||||

| 16 | cr. Mauriciano | 1 139 200 | 1 339 200 | |||||||||||

| 17 | Chabacano | 619 000 | 1 300 000 | |||||||||||

| 18 | cr. antillano | 1 200 000 | ||||||||||||

| 19 | cr. Caboverdiano | 503 000 | 926 078 | |||||||||||

| 20 | Occitan | 100 000 | 800 000 | |||||||||||

| 21 | cold | 420 000 | 600 000 | |||||||||||

| 22 | asturleon | 158 000 | 600 000 | |||||||||||

| 23 | lining | 600 000 | ||||||||||||

| 24 | cr. Meeting | 560 000 | ||||||||||||

| 25 | ligur | 500 000 | ||||||||||||

| 26 | Daddy. | 279 000 | 329 002 | |||||||||||

| 27 | cr. Cool fr. | 259 000 | ||||||||||||

| 28 | arrumano | 250 000 | ||||||||||||

| 29 | Judeospañol (including faquety) | 98 000 | 150 000 | |||||||||||

| 30 | franc-provenzal | 147 000 | ||||||||||||

| 31 | Corsoon | 125 000 | ||||||||||||

| 32 | Standard | 105 000 | ||||||||||||

| 33 | cr. seychelense | 73 000 | ||||||||||||

| 34 | lining | 69 899 | 69 899 | |||||||||||

| 35 | Aragonese | 25.556 | 56 000 | |||||||||||

| 36 | cr. of Rodrigues | 40 000 | ||||||||||||

| 37 | romanche | 35 000 | ||||||||||||

| 38 | Ladino | 31 000 | ||||||||||||

| 39 | cr. of Louisiana | 10 000 | ||||||||||||

| 40 | skirt | 6000 | 6000 | |||||||||||

| 41 | cr. angolar | 5000 | 5000 | |||||||||||

| 42 | Englishnorrumano | 5000 | ||||||||||||

| 43 | cr. palenquero | 3500 | 3500 | |||||||||||

| 44 | cr. karipuna | 2400 | ||||||||||||

| 45 | lunguyê | 1500 | 1500 | |||||||||||

| 46 | cr. Chagosiano | 1800 | ||||||||||||

| 47 | istrorrumano | 1000 | ||||||||||||

| 48 | cr. Agalega | 800 | ||||||||||||

| 49 | cr. tayo | 900 | ||||||||||||

Spanish criollosPortuguese criollosFrench criollosgalorromance languagesitalic and galoitálic languageslanguages of the Balkan group | ||||||||||||||

Origin and evolution of Romance languages

Proto-Romance intuited from linguistic comparison of the Romance languages differs markedly from classical literary Latin in its pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar. There are several theories about the origin of the Romance languages:

Theories on the origin and evolution of Romance languages

- La Traditional theory that conjecture that the romance languages come from the so-called vulgar Latin that would be continuous natural evolution of the classic Latin, whose features are defined only from the fourth or fifth centuries. It is discussed what is the relationship between this vulgar Latin and the classic Latin both regarding the time and the extension of the phenomenon. For some linguists, such as Jakob Jud, Straka and Hall, the date of fragmentation around the 2nd and 3rd centuries should be placed as a result of a natural evolutionary process of Latin, while other authors such as Meillet, Schiaffini, Tragliavini and Vidos point out that fragmentation would be associated with the decay of Roman political power and consequently at a later time. For his part Muller in 1929, based on a linguistic study of the Merovingian diplomas, a reflection, according to him, of an authentic natural language free of artifices, came to the conclusion that, indeed, the vulgar Latin was a uniform language spoken throughout Romania until the centuryVIIIand that such unity was maintained thanks to inter-provincial relations until the fall of the Empire and the institution of the Church from the German invasion, because only after the Carolingian reform and the triumph of the system ceased to act the influx of the unitive forces of that language. Other authors, such as Gustav Gröber, Mohl, Pisani, Antonio Tovar, Heinrich Lausberg and Krepinski argue that diversification would already be found in the very origins of Latin. The arguments of these authors are at the basis of the theories of absolute diglosia that we will then analyze. The main problem of traditional theory is the difficulty of explaining the very rapid evolution of the language from the classical Latin to the current languages and the relative homogeneity of the Romance languages, particularly with regard to the prepositional system against the system of Latin disindence, the system of articles or the practice disappearance of neutral gender disindence except in Romanian.

- Theory of substrates. Around 1881 the Italian Graziadio Isaia Ascoli prepared the theory that the differentiation between the Romance languages was due to the preexistence of different substrates that influenced the Latin of the different parts of the Empire. This type of theories present different variants according to the importance given to each of the linguistic substrates. Thus Ascoli emphasizes the importance of the Celtic substrate that would explain phenomena such as the case of the Vigesimal enumeration system of which there is a linguistic relict in the French "quatre-vingts". Among these theories is very remarkable the study of the phonetics prior to the Germanic invasions in western Romania and of certain processes such as the sounding of the occlusives. Maurer studies the period from 500 to 1500, pointing out as very important in this process the unifying forces after the sinking of the Roman empire that are carried out mainly by the church and the medieval Latin.

- Theory of superstrate. Other authors, such as Walther Von Wartburg, believe that the decisive factor for the disintegration of Latin linguistic unity should be sought in the dissolution of the political unity of the Empire carried out by the various Germanic stripes. The Germanic, in fact, served in the Roman army for centuries, so the contact between Germans and Romans was uninterrupted, and this is also produced at the most critical moment for the unity of the tongue. The irruption of the different Germanic peoples would determine the current composition of the Romance languages. Thus, the old franc would determine the appearance of the oil languages, while the visigothic would determine that of the oc languages and the different Iberian romances. The burgundy superstratum is held responsible for the formation of the linguistic trust between the Franco-provenzal and the Provencal in the territory comprising the southeastern part of France, the French Switzerland and part of the Italian alpine valleys. While the Italian would be in turn from the ostrogodo people and to a lesser extent from the lombard, which would explain the proximity and divergences with the oc languages. For Morf however, the distribution of Romania has as its basis the correspondence of the limits of the dioceses with the confines of the old civitates and, respectively, of the provincee, which also correspond to the original distribution of pre-Roma populations.

- Theory of fragmentation and formation of linguistic domains. Proposed by Menéndez Pidal in "Origen del español en relación a las lenguas iberorromances" and developed by Kurt Baldinger in the "Formación de los domains linguísticas", it is based on the trend to linguistic dispersal as a result of the isolation of population nuclei, and the derivative of the language in relation to its own internal demands. Thus, in the case of compact linguistic communities, the tendency will be the phonetic definition when contracting on themselves, while in those more exposed, the tendency will be receptivity to changes and phonetic dispersion. According to this theory the fragmentation of the Latin linguistic continuum led to the formation of various universes-issue as a result of the irruption of foreign linguistic domains such as Arab or Germanic invasions or the recovery of pre-Roman languages such as the Basque language.

- Theory of Diachronic Structuralism. Structuralist theories revealed an absolute preponderance of synchronic processes. For these authors there is no continuity between successive language states, since a change is but a "emergence or creation of new cultural situations". The truth is that if some authors like Max Weinreich have already tried to apply the advances of structuralism for the understanding of the evolution of the Romantic languages, it will be expected in the 1970s to address these issues from the point of view of modern linguistics. Among these modern trends, functionalism affected a more progressive conception of the problem, admitting that the evolution of a language is a constant interaction between the isolated element that changes and the system that restricts and guides the possible changes, as Roman Jakobson pointed out, “diacrony coexists in synchrony” or, what is the same, it is not possible to make a sharp distinction between synchrony and diachrony. The linguistic change does not operate on the system in its entirety, and not even on complete syntactic constructions, but acts on minimal parts or isolated elements of this

- Theory criollization claims that romance languages derive from criollized forms of Latin. A variant of substrate theory is that elaborated by Schlieben Lange and other authors who have explained this process as a result of partial integration, through the phenomenon of cryollization observed in modern languages such as French or Portuguese. In favor of this hypothesis is the one that many traits typically romances are surprisingly early.

- Theory of Journalization. Banniard's proposal combines, on the one hand, a journalization based on an absolute chronology and on the other the theory of catastrophes, addressed the linguistic changes that can occur in extreme situations, as a result of the linguistic community's need to maintain communication and the danger of disintegration. For this author, the natural evolution of the Latin language would be subject to a series of extraordinary phenomena that put at risk the very integrity of the linguistic community, which leads to the emergence of a series of solutions that break into its natural evolution. In the light of this methodological approach and considering linguistic change as a catastrophic, it establishes the fragmentation of Latin to Romance languages through absolute chronological stages, three of latinity and two of romanity.

- Theory of functional diglosia. To understand the divergences between the written and spoken language as well as the late breaking of the Romantic languages in the written documents Roger Wright holds the pervival of a graphic conventionalism that would keep the classic graphs hiding the true evolution of the language. Such deviation from the rule will result in a certain historical moment, approximately during the century and a half that goes from the Juraments of Strasbourg Until the year 1000, there is an unstable situation of persistent monolingualism, characterized, in the writing plane, by the possibility of using both traditional spelling and a new graph of phonetic type, and, in the reading plane, by the possibility of reading the written texts, as according to Wright they would have always read, that is, in vulgar, or in the new way imposed by the reform, that is, in Latin. The truth is that by the centuryX, there is a real diglosia that prevents the intelligibility of the written language. This process will lead to the extension of a superstratum of culticisms that does not yet come to root in the language and that will determine the definitive irruption in the writing of the Romantic languages in the state we know today.

- La theory of absolute diglosia. The impossibility of combining a system of dissent with the case system present in the classical Latin is the reason for being those theories that estimate that the known as vulgar Latin would be but the consequence of a long process of digression of the Latin itself spoken with previous words, but without this relationship of subordination being replaced the most original features of the spoken language. Dardel is of the opinion that the Romance languages do not descend more than part of the Latin we know by the texts. Give it part of the existence of a Latin spoken very different from the writing in certain aspects and that can be rebuilt — thanks to the help of the historical-comparative method — with the name of protorromance. Such a variety of Latin is only a part of a mother tongue that must have existed at the origin of the spoken romances, but we cannot know completely, since it is mostly a spoken language. In the temporal aspect, the mother tongue goes back to the Latin that was spoken since the foundation of Rome, but the protorromance, for reasons linked to the history of Rome and the isolation of Sardinia, probably does not go back beyond the first century before our era. Among these theories he has recently echoed in the media, published by Yves Cortez, who radically denies the philological dependence of the romance languages of the Latin Falisca language. According to this author the Romance languages would depend on another different italian language in situations of subordination to Latin. The divergence between Romance and Latin languages would manifest not only in the grammatical plane, but also in the vocabulary itself. The author considers that the peculiar way of being of the Romance languages in front of the Latin is due to a previous solution of linguistic diglosia in the Italian world prior to its European expansion and which transcended from its original framework to the entire territory of the Roman Empire. This theory has been subjected to severe criticism of the impossibility of finding references from that other Italian language.

From Classical Latin to Vulgar Latin

In ancient Rome there was diglossia: the Latin of literary texts or sermo urbanus (or 'urban speech', that is, refined) was stagnant by grammar (as it already was). Sanskrit at the same time in India). Therefore the everyday language was not classical Latin but a different though close form, in a process of freer development, sermo plebeius ('plebeian speech'). The sermo plebeius was the everyday language of the common people, merchants and soldiers and we can largely identify it with Vulgar Latin, which is known to us mainly from indirect quotes and criticisms pronounced by speakers of a Latin literary, as well as by numerous inscriptions, registers, accounts and other current texts, and by deducible evidence from the Romance languages.

First evidence

An important testimony of popular Latin is the Satyricon of Petronius, a kind of “novel” probably written in the first century of our era that passed through the marginal circles of Roman society. In it, the characters express themselves —according to their social category— in a language more or less close to the classical archetype.

Another important source of diglossia is the Appendix Probi, a sort of compilation of "errors" frequent, compiled by Marco Valerio Probo, dating from the 3rd century AD. It is these forms, and not their classical Latin equivalents, that are at the origin of the words used in the Romance languages.

The “faults” cited by Probus follow the model A non B, '[say] A, not B': for example, the correction PASSIM NON PASSI (passim, not passi) or NVMQVAM NON NVMQVA ("numquam, not numqua"), which tells the reader that the word must be spelled with a -M at the end, and that leaves one guessing that that final -M was no longer pronounced.

Some evidence of Romance-type constructions in popular Latin inscriptions is very early (many inscriptions in Pompeii from AD 79). Some authors have argued that the Romance languages do not come from the usual evolution of classical Latin, but that they could come from creole versions of said language. There are several arguments:

- Some evidence of romance-like grammatical constructions are very early, when many of the typical late Latin phonetic changes had not yet begun.

- In many regions Latin replaced languages such as cello and lepontic typeologically similar to Latin, however, the Latin of those regions seems to have had different typical characteristics since very early.

- Latin contrasts with the classic Greek, although the modern Greek has lost many characteristics of the classical language the degree of retention seems higher, even dialects far from Greece as the Greek of the Magna Greece (southern Italy) that dates back to the classical era shows a higher retention than Romanesque languages. This would have been because the ancient Greek would have evolved without cryollization.

- Slavic languages and in part some Germanic languages have retained much more easily the decline in the last two millennia even though there was no cultured language.

The creolization of Latin may have shared traits with the formation of other creole languages apart from French, Portuguese, Dutch, and Spanish. In the early stages, when there was a scarcity of speakers of the colonizing language, Romance languages may have fostered in multi-ethnic settings, due to the emergence of pidgins between people speaking different languages under the same administration. Only as the number of Latin speakers increased did the Latinized Creole become "relatinized" but without becoming the literary classical Latin. The situation may have been diglossic, so although the use of the Romanized forms of Latin may have been early, the script reflected it to a small extent, in the same way that the creole varieties were largely ignored until the independence of the former colonies.

Some of the main phonetic changes recorded both in the Appendix Probi and in other inscriptions are:

- The appearance of a phenological system of open and closed vowels with at least 4 degrees of opening /i u; e o; ε;; a/ (some authors postulate five degrees of opening by also considering the vowels / α/ as fonemas), from a system based on the vocálica quantity (in atonous position this system could be further reduced to just 3 degrees of opening, also).

- The reduction of some diptongos /au/ → /ou/ → /o/ (the reduction in /o/ was not given in galaicoportugués or in asturiano, in which it stayed in the stage /ou/, or in the west, where it stayed in /au/).

- The syncopa or fall of short postonic vowels, as in the examples collected by Probus: warm → calda 'hot', moreculus → masclus 'macho', tábula → Table 'mesa, board,' oculus → oclus 'Ojo'.

Common Linguistic Features

Although the Romance languages represent divergent evolutions of Latin, their common features are in fact almost always due to the result of retaining some linguistic aspect that was already in Latin, and in much less cases to the effect of the common influence of another language on several Romance languages. The main characteristics present in all Romance languages are the following:

- Romance languages are all merging languages.

- The dominant morphosynacetic alignment of these languages is of nominative-accusative type.

- The basic order seems to be SVO, they have preposition and the determinants generally precede the noun (although in Romanian the item is postponed).

- Presence of a verbal bending system with numerous forms and full of irregularities. The verb includes the categories of person, number, time and grammatical mode, generally varying the flexive form according to what values of this category is expressing the conjugated verbal form.

- Presence of at least two possibilities for grammatical gender (male/female), two possibilities for grammatical number (singular / plural).

- Presence of gender grammatical concordances between the noun and the adjective, and between the number of the subject and the number expressed in the verb.

- Presence of articles developed from Latin demonstrations.

Phonological processes

Up to the current situation, the Romance languages were subjected to various phonological processes that affected the supposed dialect continuum in different ways:

Plosive voicing

The most characteristic feature that divides Romania is the voicing or loss of plosives. It is thought that this phenomenon is a consequence of the Celtic group that would predominate in all of western Romania before being Latinized, since it is known that these languages ignored or greatly restricted the use of voiceless stops. That is why those plosives tend to be voiced or lost in western Romania up to the Spezia-Rimini line, according to spellings dating from the II.

Look like this:

- Latin AP/CULA/APIS Western: Bee (en), abelha (pt), abella (ca, g), abeille (fr) Oriental: Ape (it);

- Latin CEPULLA/ECA → onion (en), babola (pt, g), bar (ca), ciboule (fr) Zip (it), ceapa (ro);

- Latin CAPRA → goat (s, ca, gl, pt) chevre (fr) capra (it), capră (ro);

- Latin SAPONEM → soap (en), He knew. (ca), sabo (pt), xabom (gl) savon (fr) sapone (it), săpun (ro);

- Latin ADIUTARE → help (en), ajudar (pt, ca), axuda (gl) aider (fr) aiutare (it), ajuta (ro);

- Latin ROTARE → roll (s, g, pt, ca), rôder (fr) ruotare (it), broken (ro)

- Latin POTERE → power (s, ca, gl, pt) pouvoir (fr) potere (it), Fuck! (ro);

- Latin COGITARE → Take care care (s, st, ca), cooking (gl) Cuider (fr) cogitare (it), → Cugeta (ro);

- Latin ACUTUM → acute acute acute (it's pt, g), agut (ca), Go on. (fr) acuto (it), acut (ro);

- Latin FICARA → hose (en), figueira (gl, pt), Fig (ca), figuier (fr) ficara (it),

- Latin CICONIA → Storm (en), cegonha (pt), Blind (gl) cigonya (ca), cigogne (fr) cicogna (it);

- Latin CICADA → cigar (en, g, pt), cigala (ca), cigale (fr) cod (it), cicadă (ro).

To a lesser extent, this phenomenon is observable in fricatives:

- PROFECTU → profit (en), provided (gl, pt);

- TRIFшLIU(M) → clover (en), # (gl, pt), trèvol (ca), trèfle (fr) trifoglio (it), trifoi (ro).

This trend can also be recognized in the loss of voiceless stop consonants clustered in western Romania with different phonetic solutions, thus in the clusters P', -PS-, -CT-:

- CAPTIVU(M) → captive (en, pt);

- RAPT → steal (en), roubar (gl, pt);

- ABSENTE(M) → absent (en);

- RAP RDUS → raudo (en);

- CAPSA → caixa(ca, gl, pt), Box (en);

- DIRECTU(M) → right (en), right. (gl) Direito (pt), dret (ca);

- FACTU(M) → fact (en), fetus (gl, pt), fet (ca);

- LACTE(M) → milk (en), leite (gl, pt), llet (ca);

- NpinCTE(M) → night (en), noite (gl, pt), nit (ca);

- IACTU(M) → ♪ (pt), xeito (gl), etc.

Double stops became single: -PP-, -TT-, -CC-, -BB-, -DD-, -GG- → -p-, - t-, -c-, -b-, -d-, -g- in most languages. In French orthography, double consonants are merely etymological, with the exception of -LL- after "i".

Palatalization

Palatalization was one of the most important processes that affected Vulgar Latin consonants, a phenomenon that the Romance languages inherited, giving rise to a great diversity of solutions throughout Romania. It is for this reason that most Romance languages present palatalization of the Latin phonemes /k,g/ before a palatal vowel and of the sequences /diV-,-niV-,-tia,-tio/ (where V denotes any vowel).. However, there is an important division between the Western Romance languages, with /ts/ resulting from the palatalization of /k/, and the remaining Italo-Romance and Balco-Romanian languages reaching the solution /tʃ/. It is often suggested that /tʃ/ was the result of a previous preceding solution, this would explain the relative uniformity in all languages at first, with /tʃ → /ts/, later giving way to a great variety of solutions in all Western Romance languages given the enormous instability of the phoneme /ts/. Proof of this is the fact that Italian has two /ttʃ/ and /tts/ as palatalization results in different situations, while the rest of the Western Romance-derived languages have only /(t)ts/. It is also often pointed out how some variants of Mozarabic, in the south of Spain, adopted the solution /tʃ/ despite being in the area of "Western Romance" and geographically disconnected from the remaining areas where the solution /tʃ/ is reached, which suggests that the Mozarabic languages, due to their peripheral character, preserved the common preceding solution, where the change /tʃ/ → /ts/ had not yet been reached. In other peripheral areas such as Northern French dialects such as the Norman dialect or the Picardy dialect, they also presented the solution /tʃ/, but this may be the consequence of a secondary development. It should also be noted that /ts, dz, dʒ/ eventually became /s, z, ʒ/ in most Western Romance languages. Thus, the Latin expression CÆLUM, which was originally pronounced [ˈkai̯lum] with an initial /k/, became Italian zeal [tʃɛlo], Romanian cer [tʃer], Spanish cielo [θjelo]/[sjelo], French ciel [sjɛl], Catalan cel [sɛɫ], Galician céo [sɛw] and Portuguese céu [sɛw]. The effect of palatalization, however, has not always spilled over into writing systems, and so in many of the Romance languages, where the letters C and G have the original pronunciation /k/ and /ɡ/, modify their pronunciation in late Latin and before the palatal vowel Æ, E, I. Thus the phonemes /k, g/ gave in French Portuguese, French, Catalan and Occitan /s, ʒ/ and in Italian and Romanian /tʃ, dʒ/. In addition, in Spanish, Catalan, Occitan and Brazilian Portuguese, the use of <u> to indicate the pronunciation before <e, i> means that a different spelling is also needed to mark the semiconsonantal sounds /ɡw, kw/ (Spanish <cu, gü>, Catalan, Occitan and Portuguese <gü, qü>). This produces a series of spelling alterations in verbs whose pronunciation is totally regular but whose written expression diverges from the general rule.

Some examples of this process are as follows:

- vinea → vianda → ♪nya 'Viña'

- diurnum 'diurno' → ♪dyOrno → it. giOrno 'day', fr. jour 'day', esp. jornal 'salary of one day' and jornada 'for a day'.

- Cuniculum ' Rabbit' → Coneclor → Catalan conill, Spanish Conejor, Galician ♪llor, asturleon Coneandu.

- oculus 'Ojo' → orclus → cat. ull, esp. orjor, gal. orllor, asturleon güeandu.

- In several Romance languages, not all, /kt/ → /yt/ (vocalization, iodization), lacte → ♪ → ♪ → Catalan llet 'leche', in some you give a full palatalization /yt/ → /*yč/ palataliza ♪ → milk. In Galician it is said leite and asturleonian (West) lleite.

- Similarly in several of the previous languages, /lt/ produces /jt/ (vocalization, iodization) multum → ♪ → ♪ in Portuguese and Asturleonés (West), with full palatalization in other languages such as Spanish ♪ → a lot.. A decreasing diptongo occurs in Galician: Moito.

- In some languages such as Catalan and Asturleonian there is palatalization of /l-/ Latin initial: legere → Catalan llegirAsturleon lleer or llïere.

- In asturleonés and in the north-western varieties of the extremeño there is palatalization of /n-/ Latin initial: nurus → Extremadura and asturleonés ñuera.

Velarization

Kurt Baldinger, Tovar and other authors appreciate a phenomenon common to much of Western Romania, which is the velarization of nasal and lateral sounds as a consequence of a previous pre-Roman stratum that would extend along the entire Cantabrian coast until the still unromanized Basque area today, continuing throughout the south of France to the north of Italy. This feature would be manifested in the loss of the intervocalic nasals and laterals, but also in the vocalization of the lateral codas in Occitan or in the nasal vocalism in Portuguese and French. Gamillscheg has highlighted how in the Galician-Portuguese area, on the one hand, and in the Basque-Gascon area, on the other, a progressive nasalization has taken place, as opposed to the only regressive nasalization that occurs in the rest of Gallo-Romania, because together with the phenomenon of the -n- expires, it is also postulated that of the nasal vocalism and the nasalization of many of the final solutions lat. multum → port. before veryn, ast. → a lot. As Baldinger points out, it is not just the fact of the well-known loss of intervocalic -n- lat. crown → port. coroa, lat. planum → port. chao, lat. honore → as a loan in Basque oore; The t. channel → gasc. càu, what the two separate areas have in common, but the type of nasalization. The fact that this phenomenon does not occur in the central dialects of Asturias and Cantabria, according to Gamillscheg, indicates that the imposition of Spanish has eliminated in Cantabria and Asturias a trend that is evident in the west and east. In this sense, the system of indefinite articles in the Sobrescobio dialect 'uo', 'ua', 'uos', would be preserved as a relic of this phenomenon in Asturias. 'uas', the loss of all traces of nasality in certain expressions: nominem → nome, hominem → home, luminem → lume or certain place names cited by Tovar: Ongayo → Aunigainum, Bedoya → Bedunia.

Final Codas

The loss of the case system notably affected the final consonantism, which tends to weaken. Along with the tendency to eliminate final consonants in Vulgar Latin, there is a tendency towards the loss of entire groups (apócope) or the addition of a vowel after the last consonant to reinforce its sound (epenthesis). In the Italo-Romance and Oriental Romance domain. Over time all final consonants decay or are reinforced by a vowel epenthesis, except in monosyllabic forms (for example, the prepositions 'with', 'by', etc.). Modern Italian still hardly has consonant-final words, although in Romanian they seem to have re-emerged due to the later loss of the final vowel /u/. For example, you LOVE "love " → love → love; amant → love → amano. In Italian the plural formation system, with the well-known loss of the 's' The end did not occur until the 7th century or VIII d. C., after a long period. It is believed that the consonant 's' was palatized into 'j' instead of just disappearing: 'us' → noj → ' noi' "we", 's' → 'sej' → 'sei' "are you"; cras → craj → crai "tomorrow" (Southern Italy). In unstressed syllables, the resulting diphthongs were simplified: amicas → 'amikai' → 'amiche', where the Latin term 'amicae' plural nominative gave rise to 'amito' instead of amiche → amici. For their part, the Central and Western Romance languages eventually recovered a large number of final consonants through the general loss of final /e/ and /o/, for example, llet "leche& #3. 4; Catalan ← lactem, foc "fire" ← focum, peix " fish " ← piscem. In French, most of these secondary final consonants were lost, but tertiary final consonants would later arise as a consequence of the loss of the 'ə'.

Reduction and stabilization of tonic vocalism

Tonic vocalism is reduced to four degrees of openness (open, semi-open, semi-closed, and closed), and three degrees of localization (anterior, central, and posterior). This system will give rise to the typical vocalism of seven tonic units (/i u; e o; ε ɔ; a/) which in Spanish will be simplified to five by substituting the semi-open vowels ɛ and ɔ for the diphthongs 'ie' and 'ue' respectively (diphthong). Some authors postulate five degrees of opening (by also considering the vowels /ɪ ʊ/ as phonemes), based on a system based on vowel quantity (in an unstressed position this system could be further reduced to only three degrees of opening, a reduction that Spanish also applied to stressed vowels).

The evolution of the vowels is compared in the following table:

Evolution of the tonic vowels Classical Latin . Œ . . ♫ . AU Å ♫ Protorromance Western ♪ ♪ * ♪ * ♪ ♪ ♪ East ♪ ♪ * ♪ ♪ ♪ Iberorromance Spanish i e e YEAH. ä we̯ o̯ u Leon i e/ei Heh. ä we/wo/wa, u ou/o, u or u mirandés i e e j/i/e/ ä w//u ouu o̯ u Portuguese i e/ei ‐ oi or u Galician i e/æi ‐ ä ou or u Occitanorromance Catalan i e ‐ ä or u Occitan i e deployment/j ä /// au u and Galorromance French i oi ie a/e we eu u French i wa ie a/e What? ø and Galloitálico piamontésturinés i ‐ e a What? u and Lombard i e/i e a/e What? ø and Italorromance Italian Standard i e ifold/ a w/// or u Sicilian i ‐ a u Retorromance romanche i/ ai/e * transformation → ia a/au *u → → o/œ or u Ladino i ai/ei ia/i a/e (u)u/u(o) or u cold i e ia/i a wo or u Balcorromance Romanian i e//ä ie ä/ o̯ u Sardinian i e e ä o̯ u

Weakening of unstressed vocalism

The unstressed vocalism tends to weaken, disappearing in some cases, such as the unstressed e and o in French and Catalan, and to be reduced to three archiphonemes Portuguese and to a lesser extent Spanish.

Transformation of the morphosyntactic system

Romance languages are characterized by a reduction in declension (grammar) both in number of cases and in different paradigms. Presumably this was caused by some phonetic changes affecting final consonants and also as a result of morphological analogy.

The only modern Romance language that has case marks on the noun is Romanian, which retains three different cases, while Latin had five basic cases (or six if one counts the vocative, which was rather defective. Marginally there were also traces of locative, only applicable to places Rōmae 'in Rome' and domī 'at home'). Of the earliest attested Romance languages, only Old Occitan and some varieties of Romansh also had cases, but the modern varieties no longer have case opposition. Likewise of the three genders of Classical Latin, most languages only retain two in the noun (some in the pronoun and articles still retain the neuter gender). The grammatical number has been preserved without important modifications, existing singular and plural in all languages.

Verb inflection retained to a much greater degree the variety of categories and distinct forms of Classical Latin, although the synthetic passive voice forms were completely lost in all languages, being replaced by analytic constructions. A similar fate befell a large part of the perfect forms, which were replaced by analytic constructions.

Noun system

The drop of the final /m/, a consonant often found in inflection, then creates an ambiguity: Romam is pronounced as Roma, so one cannot tell if the term is in the nominative, accusative, or ablative. To avoid such ambiguity, Romance languages have to use prepositions. Before saying Roma sum for 'I'm in Rome' or Roma(m) eo for 'I'm going to Rome', these two sentences had to be expressed by sum in Roma and eo ad Roma. In this regard, it should be remembered that if -already in classical Latin, since imperial times— the word-final /m/ was omitted, Roma sum could not be confused with Roma(m) eo: in the ablative (Roma sum), the final /a/ was long; instead it was brief in the accusative: in the first it was pronounced /rōmā/, and in the second /rōmă/. Vulgar Latin, however, no longer used the vowel quantity system: both forms are somewhat ambiguous.

In the same movement, adverbs and simple prepositions are sometimes reinforced: ante, 'before', no longer enough; put ab + ante in vulgar, to explain French avant, Spanish antes and Occitan and Catalan abans, or in ante for Romanian or Astur-Leonese înainte and enantes respectively, etc.; similarly, in French, avec comes from apud + hoc, dans from de intus, etc.

The limiting case seems to be reached with the French aujourd'hui, a notion that was simply said hodie (in turn «this day») in classical Latin. The French term is parsed into à + le + jour + de + hui, where hui comes from hodiē (found in Spanish “ hoy”, in Occitan uèi, in Italian oggi, in Astur-Leonese güei, in Romansh hoz or in Walloon oûy). The resulting agglutinated compound is, therefore, redundant, since it means, term by term: 'today' (in French au jour d'aujourd'hui).

Certain conservative languages, meanwhile, have kept simple adverbs and prepositions: Spanish “con” and Romanian cu come from cum, as well as en or Romanian în are inherited from in. This phenomenon is also seen with simple terms inherited from hodiē.

From an inflectional language with an agile syntax (the order of the terms does not greatly affect the meaning but mainly the style and emphasis), Vulgar Latin became a group of languages that used many prepositions, in which the order of the terms is fixed: if in Latin it is possible to say Petrus Paulum amat or amat Petrus Paulum or Paulum Petrus amat or even amat Paulum Petrus to mean that 'Peter loves Paul', this is not possible in the Romance languages, which have abandoned declensions more or less quickly; Thus, in Spanish "Pedro loves Pablo" and "Pablo loves Pedro" have an opposite meaning, only the order of the terms indicates who is the subject and who is the object.

When the Romance languages maintained a system of declensions, this has been simplified and is limited to those cases (with the exception of Romanian): what happens in Old French and Old Occitan, which only have two: the subject case (inherited from the nominative) and the object case (from the accusative), for everything that is not a subject. In these languages, almost always, the subject case disappeared; the current nouns inherited from the old language are then all of the old object case and therefore of old accusatives; It can be seen with a simple example:

| Classical Latin | Old French and West | Modern French and West | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | plural | singular | plural | singular | plural | ||||

| nomination | murus | muri | case | murs | mur | - | - | ||

| accusing | murum | walls | case object | mur | murs | mur | murs | ||

Romanian, however, preserves an inflectional system that works with three syncretic cases: “direct case” (nominative + accusative), “oblique case” (genitive + dative) and “vocative”. These cases are distinguished mainly when the noun is marked by the definite article. Otherwise, they have a tendency to be confused.

Other points are worth noting:

First, excluding Romanian and Astur-Leonese (which maintains it for uncountable substances, such as agua and fueya ['hojarasca']), the three genders, masculine, feminine and neuter, are reduced to two by the elimination of the neuter. Thus, the Latin term folia —nominative and accusative neuter plural of folium, 'leaf'— is reinterpreted as a feminine. This is the case, for example, in Spanish, where it becomes hoja, but also in French feuille, in Italian foglia, Romansh föglia, Walloon fouye, Portuguese folha, Catalan fulla, Occitan fuèlha etc. (all feminine terms).

In addition, the Romance languages developed a system of definite articles, unknown in classical Latin. Thus, in Spanish, “el” and “la” come respectively from the demonstrative pronouns and adjectives ille and illa (plus a neuter “lo” ← illud); equally in Italian for il and la (as well as lo ← illum), in French for le and la from the demonstratives illum and illa respectively, etc. Romanian is distinguished by being the only Romance language in which the article is postponed: om ('man'), om-ul ('the man'). The indefinite articles, for their part, come simply from the numeral unus, una (and unum in the neuter), which, in Latin, would have could serve with this use.

Finally, the adjective system is reviewed: while the degrees of intensity were marked by suffixes, the Romance languages only used an adverb before the simple adjective, either magis (which became “más” in Spanish, mai in Occitan and Romanian, mais in Portuguese, més in Catalan, etc.) and be plus (più in Italian, plus in French, pus in Walloon, plu in Romansh, etc.). Thus, to say “greater” (comparative of superiority) in classical Latin, grandior was enough. In Spanish, “más grande” is needed, in Italian più grande, etc. Likewise, the superlative “the greatest” was said grandíssimus in classical Latin, but “the greatest” and il più grande in those same languages.

Verbal system

Latin conjugations were profoundly modified, mainly by the creation of compound tenses: thus our “I have sung”, the French j'ai chanté, the Occitan ai cantat or the Catalan he cantat come from a vulgar habeo cantátu(m), which does not exist in classical Latin. The use of auxiliary verbs "to be"/"to be" and "to have"/"to have" is notable: Latin already used "to be" in its conjugation, but not as systematically as in the Romance languages, which have generalized its use to create a complete set of compound forms responding to the simple forms. Compound forms generally mark the finished aspect of the action.

A new mood appears, the conditional (attested for the first time in a Romance language in the Sequence of Santa Eulalia), built from the infinitive (sometimes modified) followed by the endings of the imperfect: vivir + -ía generates “viviría” in Spanish, Astur-Leonese, Galician and Portuguese, as well as “vivrais” in French, “viuriá” in Occitan, “viuria” in Catalan. Note some of the root modifications: “haber + ía” → “habria” and not “*haberia” or devoir + ais → devrais and not *devoirais. Similarly, the classical future is abandoned by a formation comparable to that of the conditional, that is, the infinitive followed by the verb to have (or preceded, as in the Sardinian case): thus cantare habeo (' yo he de cantar') gives “cantaré” in Spanish and Catalan, cantarai in Occitan, cantarei in Galician, Leonese and Portuguese, je chanterai in french etc

The passive form is eliminated in favor of a compound system that already existed in Latin (cantátur, 'it is sung', in classical Latin it becomes est cantatus, which in classical Latin means 'has been sung'). Finally, some irregular conjugations (such as volle, in French "vouloir") are rectified, although many maintain their irregular character in Romance languages, and deponent verbs are no longer used.

The Lexicon of Vulgar Latin

To a large extent the lexicon was preserved in the Romance languages, although a portion of the classical Latin lexicon that appeared in more formal contexts was replaced by more popular terms, eliminating from use the terms proper to the most cultured language.

Some Latin words have disappeared entirely and have been replaced by their popular equivalent: horse, equus in Classical Latin (where "equitación" would come from in Spanish, for example, or "equine" as a synonym for "horse"), but caballus (a word, perhaps, of Celtic origin meaning 'penco' or 'hamelgo') in Latin vulgar. The word is found in all Romance languages: caval in Occitan, cavall in Catalan, cabalo in Galician, caballu in Astur-Leonese, cavallo in Italian, cal in Romanian, chavagl in Romansh, cheval in French, tchvå in Walloon etc.

On the other hand, if certain classical terms have disappeared, they have not necessarily always been replaced by the same Vulgar Latin word. The classical Latin learned term for 'speak' is loqui (pronounced "locui"). It was replaced by:

- parabolāre (word taken from the Christian and Greek liturgy; literally ‘talk with parables’): Italian Parlare, Aragonese, Catalan and Occitan parlar, French parler, extremeño palraletc.;

- fabulāri (literally: ‘fabular’, talk about or make fables): Spanish “talk”, Galician, Asturleon and Portuguese skirtAragonese fablar, sardo faedhàreetc.

Finally, some Romance languages continued to use the classical forms, while others, less conservative, used the vulgar forms. The example traditionally used is that of the verb "to eat":

- classic edere: it is in a composite form — and therefore less “noble” — in Spanish, Galician and Portuguese eat (de) comedere);

- Latin manducāre (literally ‘masticar’): in French MangerOccitan Manage, Italian mangiareAragonese mincharCatalan Men, or in Romanian to mâncaFor example.

As for the oldest borrowings, these came mainly from Hellenistic Greek (Koine) and Germanic languages (mainly Gothic). Beginning in the 10th and 11th centuries, there were also a number of borrowings for technological and scientific concepts from Classical Arabic. More recently, cultisms and neologisms were introduced from classical Greek and Latin roots (the latter are characterized by not presenting the typical phonetic changes of the patrimonial lexicon) and also a good number of words from other languages for plants, animals and realities that the Europeans encountered in their colonial expansion. Currently the main source of lexical borrowing in Romance languages is English, especially influential in technology, business and economics lexicon or cultural fashions.

The reasons for the diversity of Romance languages

There are various sociolinguistic factors to explain the appearance of distinct linguistic varieties in each geographical region, which over time would give rise to different languages, in some cases with very little mutual intelligibility.

Divergent Theory of Evolution

The natural phonetic evolution of all languages—to which Latin was subject—explains the important differences between some Romance languages, after a period of semi-independent evolution of some eighteen centuries. Added to this process is the already existing lexical diversity in what is called “vulgar Latin”. The size of the Roman Empire and the absence of a stable linguistic cohesion guaranteeing a common literary and grammatical norm resulted in divergent evolutions that cumulatively gave rise to vernacular languages that were not mutually intelligible.

For this reason, each zone of the empire geographically connected in a strong way only with the adjacent zones, used a particular modality of Vulgar Latin (one should even say “of the Vulgar Latins”), as seen above, a language preferring a term to say “house” (Latin casa in Spanish, Galician, Catalan, Italian, Sicilian, Portuguese, Romanian), another language preferring a different term (mansio for the same meaning in French maison) and another preferring the term “domo” (domus in Latin) in Sardinian, for example.

Substrate theory

To the differentiation by divergent evolution is added the hypothesis that the Latin spoken in different areas of origin had its own accent and characteristics, due to the fact that, initially, it was a language learned by speakers who previously spoke different languages. This fact is known as the influence of substrate languages: languages initially spoken in one area and covered by another, leaving only scattered traces, both in vocabulary and in grammar or pronunciation in the target language. Thus, the Gallic substratum in French leaves about 180 words, such as braies, char or bec and would be at the origin of the passage of the sound /u / (from lunana) Latin to /y/ (from lune). Naturally, the influence of Gallic was not limited only to France: Portuguese or the dialects of northern Italy, for example, have taken some terms.

Some scholars also consider that a language that served as a substrate for the Ibero-Roman languages was Basque, which possibly contributed to the change /f/ to /h/ at the beginning of words in Spanish (Latin farina became “flour”), and words like “left” (Basque ezkerra).

Or even Etruscan – which had already been influencing Latin since the beginning of its history – for the Italian dialect of Tuscany, which owed its Tuscan gorgia, that is, the pronunciation of the sounds /k/ as / h/ (English home) or /χ/ (German Bach; Spanish jota).

It should be noted that both the Basque and Etruscan substratum theory are currently discredited.

Although this factor is easily understandable, it does not explain most of the changes. In fact, several modern languages such as Spanish, English or French have spread over wide geographical areas, being learned by people who previously spoke other languages. However, a large part of the differences found between the Spanish, English or French dialects of each region generally bears little relation to the type of pre-existing substratum. For that same reason, the influence of the substratum could have had a limited influence on the Latin of each region, this influence being only appreciable in the lexicon and to a much lesser extent in phonetics or grammar.

Superstratum Theory

Finally, the superstratum has also played an important role in the differentiation of Romance languages: they are the languages of peoples who, having settled in a territory, have not managed to impose their language. However, these languages leave important traces. The Frankish (ie Franconian Germanic) superstratum in France is important; the medieval vocabulary is full, especially in the field of war and rural life (thus adouber, flèche, hache, etc., but also framboise, blé, saule, etc., and even garder and surprisingly trop).

Current French has hundreds of words inherited from Germanic languages. Spanish also has words inherited in this case from Gothic (from the Visigoths) or other Germanic languages; words like "war" or those already seen in French "adobar", "arrow", "ax", "raspberry", "save", even names like Alfredo, Bernardo, Eduardo, Federico, Fernando (or Hernando), Gonzalo, Guillermo, Roberto, Rodolfo, Rodrigo, etc.

But the most noticeable superstratum in Spanish is Arabic: more than 4,000 words come from that language, including place names and compounds. The most remarkable characteristic is the almost systematic maintenance of the Arabic article in the word, insofar as the other Romance languages that have borrowed the same word have often gotten rid of it.

Thus, algodón (opposite French coton, Catalan cotó Asturleonese cotón) from Arabic al quṭun; "carob" (French caroube, Catalan garrofa, Leonese garrouba") from al harūbah; or also "customs" (French douane, Catalan duana) from al dīwān (which also gives “diván”).

Finally, Romanian owes to the neighboring Slavic languages the vocative, some lexical terms as well as palatalization and velarization processes different from other Romance languages.

Degree of diversification

The results of a study carried out by M. Pei in 1949,[citation needed], which compared the degree of evolution of the various languages with respect to their mother tongue; For the most important Romance languages, if only stressed vowels are considered, the following evolution coefficients are obtained with respect to Latin:

- sardo: 8%;

- Italian: 12%;

- Spanish: 20%;

- Romanian: 23.5%;

- Catalan: 24%;

- Occitan: 25%;

- Portuguese: 31%;

- French: 44%.

Thus, it is possible to easily see the degree of variability of the conservatism of the Romance languages. The closest to Latin phonetically (considering only the tonic vowels) is Sardinian, the furthest away, French. This study is indicative but reflects a true reality, although it can lead to errors. For example, the vowel variety of French, from the Middle Ages to the present, has been reduced, thus not having an involution of the language, and Castilian, instead of changing the vowel timbre, has developed a series of diphthongs that distinguish between the old Latin short and long vowels. Regarding other aspects of languages, such as the lexicon, Romanian is the one that has distanced itself the most from Latin.

Family languages and internal classification

First of all, it should be clarified that up to now there is no unified and scientific classification regarding the groups and subgroups of the Romance linguistic varieties that are universally accepted. However, traditionally classifications have been used in which languages are grouped according to geographical areas, also taking into account distinctive phonetic and grammatical features. According to these criteria, Eastern Romance languages are considered those that form the plural using vowels (generally -i or -e), do not palatalize the intervocalic group -cl and do not the voiceless intervocalic plosives /p, t, k/ of Latin origin are voiced; while those varieties that voice intervocalic /p, t, k/ belong to Western Romania, form the plural with -s and palatalize the intervocalic -cl. In addition to other linguistic developments that separate said groups under the Massa-Senigallia Line.

On the other hand, it should be taken into account that when referring to a «Romance language», this can in turn include several dialects (for example, Romance languages are traditionally considered a single language with three main dialects, although the intelligibility between them is difficult). The problems in the classification are due to the fact that the tree model (Stammbaumtheorie) is not adequate to describe the differentiation of a language family in the presence of language contact, as Johannes Schmidt pointed out when proposing his "wave theory" (Wellentheorie). In addition, it must be borne in mind that the Romance varieties form a dialectal continuum whose mutual differences are sometimes minimal, becoming mutually intelligible in most cases (more in writing than orally, although easily intelligible).

Exact internal classification is one of the most difficult problems within any language family. Outside of first-level groups of linguistically very closely related varieties, it is difficult to establish a cladistic tree since languages influence each other in their historical development and the phylogenetic tree model is not adequate to represent the linguistic differentiation of a set of languages in contact. An enumeration of the groups that most likely constitute valid phylogenetic units is as follows:

- Languages iberorromances (gallego-portugués, astur-Leonés, Spanish or Spanish and Aragonese by some considered occitanorromance)

- Galloromance languages (French/Lenguas de oïl y franco-provenzal)

- Retouching languages (romanche, friulano and ladino)

- Occitan-Romance languages (catalan-valenciano and occitan-gascon)

- Galloitálic languages (ligur, piamontés, lombardo, emiliano-romañol, véneto and istriano).

- Italian languages (standard Italian, Romanesque, Neapolitan, Sicilian and Corso-gallurés)

- Balcorruman languages (standardrum, arrumane, meglenorrumano and istrorumano)

- Island romance languages (sard and old corso)

- Other extinct Romance languages (Mozarbe and Dalmatian)

In turn, the authors proposed two branches to classify these groups based on the aforementioned isoglosses:

- Western Romance languages (iberorromance tongues, occitanus, galorromances, re-Romances, galoitálicas, Mozárabe and island romances)

- Oriental romance languages (Romans, italorromances and Dalmatian)

The exact relationship between these groups is a matter of discussion and there is no single accepted classification, so different authors based on different types of evidence and criteria have made classifications that group these groups differently. Based on the lexical similarities computed by the ASJP comparative project and other linguistic evidence, a branching tree results as follows:

| Romance |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Western Romance

Iberorromance group

- Spanish or Spanish (principles of the 9th century: Valposed cartridges): Spanish official language. It is the official language in most countries of Latin America, Equatorial Guinea and was the official language of the Philippines and Guam until after World War II. In the United States of America, 12 per cent of the population over 5 years of age speaks Spanish (about 30 million people).

- Portuguese (português, s. XII): official language of Portugal, Brazil, Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Sao Tome and Principe and East Timor. Provider of medieval Galician.

- Gallego (Greek, s. XII): co-official language of Galicia along with Spanish. Provident of medieval Galician (during the Middle Ages Portuguese and Galician were the same language, which emerged in the 9th century).

- Aragonese language, spoken and written in Aragon, currently restricted to various parts of the north of that region.

- Asturleonés (S. IX, Nodicia de Kesos) linguistic group of the Iberian peninsula that constitutes a single language with different dialects:

- Asturian (Asturianu): name that receives this language in the Principality of Asturias and regulated by Law in the autonomous field.

- Leonés (Llionés): name that receives this language in the autonomous community of Castilla y León, in the provinces of León, Zamora and Salamanca. Officially recognized in the Autonomy Statute of that community.

- MirandésMirandês): name that receives this language in Miranda de Duero (Portugal). It is an official language along with Portuguese.

- You speak of transition between Castilian and Asturleonian:

- Mountaineering (Cántabru): name received this speech in Cantabria, spoken in the western part of the autonomous community and in some valleys of the east.

- Castor (Estremeñu): Speaking in the north of Extremadura and south-west of Salamanca.

- Some authors include Catalan and even West-Roman languages within the iberorromance.

There is also a language from the Iberian Peninsula for which there is no agreement on how to classify it:

- Mozárabe (he dialectal disappeared towards the thirteenth century) spoken in the south of the peninsula in the historically under Muslim domination.

Ethnologue classifies it together with Aragonese as Pyrenean-Mozarabic languages (although there do not seem to be common isoglosses exclusive to these two languages). For others, Aragonese has intermediate features between nuclear Ibero-Romance and Occitano-Romance, although there is no philological consensus regarding its classification.

Occitan-Romance group

These two very close languages form a transitional dialect continuum between the languages of Oil and Ibero-Romance, called Occitan-Romance. Some sources classify both among the Gallo-Romance languages, others, such as Ethnologue, within the Ibero-Romance group and, traditionally, Catalan as Ibero-Romance and Occitan as Gallo-Romance. The so-called Pyrenean Romanesque Group, a bridging group between Ibero-Romanesque and Gallo-Romanesque, made up of Occitan, Catalan and Aragonese, is gaining more and more strength among Romanists.

- Catalan: (català, end of the X), co-official language in Catalonia (Spain) together with the Spanish language, is spoken in the autonomous community, as well as in the Valencian Community (where it is called Valencian), in the Balearic Islands, as well as in the eastern end of Aragon known as The Strip (where it is considered its own language), some pedanías in the natural region of El Carche (Region of Murcia), Andorra (France) He has several dialects.

- Occitan (West or oc language, end of the X), term covering a set of called dialects oc language— mainly the north west (lemosin, the winter, and vivaroalpine), the middle-west (languedociano and Provezal) and the gascon—and known in France with the derogatory name of patois (patuá). In Spain we speak the Aranese, speaks gascona of the Aran Valley.

- Some authors are trying to include the Aragonese in the west.

Gallo-Romance group

- Francoprovenzalfrancprovenzal or Arpitán, s. XIII, Méditations Marguerite d'Oingt), is a group of languages divided between Italy (Valle de Aosta and Piedmont), the Switzerland Romandy (Freiburg, Valais, Vaud and Geneva and South of the Jura canton), France (Lyon, Saboya and South of the Franc County), it is believed that the Franco-provenzal is the transition between the languages of oïl and the languages. He's in danger of extinction.

- French (français, s. IX, Juraments of Strasbourg): or also language of oïl is a language with great dialectal variety belonging to the languages of oïl and official language of France and co-official in Belgium, Switzerland and 26 other countries. It is an evolution of several dialects spoken around Paris (this if the Creole languages like those of Haiti are not counted).

- Varieties of oïl: The languages or dialects of oïl are a group of galorromance varieties spoken in the north of France and Belgium that descend from the old French, the varieties of oïl are:

- Burgundy

- Berrichon

- Champagne

- Franco-comtés

- Galó

- Valon

- Picardo

- Norman

- Lorenés

- Poitevin-Santongés

- Angevin-mayen

All these varieties are seriously threatened with extinction, the French government has recognized the languages of oïl as languages of France but prevents them from signing the charter of minority languages and giving them any kind of status or protection, the only languages of oïl that has protection and status as a regional language are (Walloon, Picard and Champagne) in Belgium and Norman has obtained status and protection in the Channel Islands. These varieties can also be classified as dialects of French or as separate languages since the term lengua de oïl (language of itself) is a synonym of French, which implies that the Romance varieties derived from this language are dialects of French since it contracts with Occitan (languages of òc), however another term affirms that in the north of France and Belgium a group of Romance languages derived from the language of oïl are spoken and that French is a descendant variety of this language. In this case it would be necessary to argue that these varieties are sister languages of French since in France and Belgium they are considered separate languages, however Ethnologue and traditional Romance linguistics consider them dialects of French, but there is no accepted classification.

- Some authors expand the Galloromance languages, including the Galloitálic languages (excluding the véneto), the re-Romantic languages and the West-Roman languages (in some cases including Catalan).

Retorromance group

The Rhathero-Romance languages are a set of closely related linguistic varieties spoken in southern Switzerland and northeastern Italy (Roman province of Recia). Linguistically they share notable features with the Occitan-Romance and Gallo-Romance languages.

- Dialectos romanches (rumantsch): South-Sylvane, South-Warm, Puter and Vallader form the five written dialects, speak in Switzerland (in the canton of the Greys), at present the number of speakers of all these dialects assembled just frieze the 35,000 people.

- Interromanche (rumantsch grischun): species of lingua franca romanche used in Switzerland to unify the 20th of Roman dialects, and which is mainly supported in the south, the vallader and the southmirano. The interromanche is an official language in the Swiss canton of the Grisones.

- Dialectos ladinos (ladin): employees in the Dolomites (Italy), are considered a regional language.

- Friulano (furlan): spoken in the Italian province of Údine and parts of the provinces of Pordenone and Gorizia, has regional language status.

Galloitalic group

The Gallo-Italic languages have transitional characteristics between the Central and Southern Italian varieties and the other Western Romance languages. The Gallo-Italic languages have a total of about 15 million native speakers in northern Italy. Although none of them have official recognition by the Italian State, several of them have been recognized and are the subject of protection laws by regional parliaments. The commonly recognized Gallo-Italic languages are:

- The foothills.

- The ligurine.

- Lombard.

- The emiliano-romañol.

- The funnet, which is the most divergent language of the rest and the closest to the italorromance group.

- The istrian, closely related to the vereto.

Sardinian

Sardinian (sardu or limba sarda, 11th century), spoken in Sardinia. It is one of the most conservative Romance languages, which can be explained by its geographical isolation. It is considered that the Sardinian group constitutes the first branch broken off from the rest of the Romance languages, since all the others present a common vowel evolution that is not present in Sardinian. Several Sardinian dialects are distinguished:

- Campidanés (campidanesu): South language variant.

- Achievements (logudoresu): linguistic variant of the center-northwest, in which most literary works are written.

- Nuorés (nugoresu): language variant of the center-east.

The last two linguistic variants have many aspects in common with respect to the first. Regarding its phonetic and grammatical features (voicing and fricatization of Latin intervocalic voiceless stops, formation of the plural by means of -s, etc.), Sardinian belongs to the Western Romance languages, despite the fact that Ethnologue classifies it (along with the Italian varieties of Corsica, and Gallurés and Sassarés) within the insular Romance languages. Since the Middle Ages, Sardinian has known numerous superstrata, among which Catalan, Spanish, Ligurian and Italian are the most relevant.

| Spanish | Sardo (Logudorés) | Sardo (Nuori) | Sardo (Campidanés) |

|---|---|---|---|

| el, la, los, las | his, sa, sos, sas | his, sa, sos, sas | his, sa, is |

| water | abba | abba | water |

| Four | Bàtoro | Bàtoro | Cuatru |

| tongue | limba | limba | lingua |

| pleasure | piaghere | piachere(a) | praxeri(b) |

| voice | boghe | #(a) | Boxi(b) |

- (a)where ch reads like a k.

- (b)where the x reads like the j French jamais or Heh..

Oriental romance

Italorromance group

The Italian-Romance languages (Italian, Romanesque, Neapolitan, and Sicilian) are a dialect continuum from the center to the south of the Italian peninsula, often referred to only as Italian dialects. This group shares the southern and eastern isoglosses of the Massa-Senigallia Line.

- Tuscan

- Italian (Italian, s. IX), historically derived from the Florentine Tuscan, promoted by Dante in the thirteenth century constitutes the basis of the Italian official language.

- Corso. It is considered an Italian historical dialect, derived from the Tuscan, which has suffered a strong French influence over the last two centuries. However, Ethnologue ranks it apart from the Italian between the South Romanesque group (or the Insular Romanesque), along with the Sardinian varieties. It is typical of the French island of Corsica. The gallurés and sassars, spoken in the north of Sardinia, are often considered dialects of the corso although strongly influenced by the sardo, or intermediate dialects between corso and Sardinian.

- Romanesco or central Italian includes several dialects spoken in the center of Italy, especially in Rome, in the Central-September Latium, in Umbría and in the central area of Marcas.

- Napolitano or southern Italian includes the dialects of central-south Italy such as those spoken in the Southern Latium and in Campania, as well as the Farish, Lucan and Northern Calabrian dialects.

- Sicilian ( 'u sicilianu) or extreme southern Italian, spoken in Sicily and in the southern extremities of the italic peninsula: Salento (in the variant known as the Saltino) and Calabria (central and southern cod). A italorromance language that presents certain influences of superstrate mainly from the Byzantine Greek, and, to a lesser extent, of lexicon loans from other continuums of more distant romances such as the Occitanorromance and the iberorromance, and of non-Roman languages such as the Arabic language; as well as a substrate from the ancient languages of the Sicans (preindoeuropeos),

- Eight key dialects are distinguished in Sicily and nearby islands:

- Western (Provinces of Palermo and Trapani).

- Centro-Occidental (Province of Agrigento).

- Central Metaphonic (Enna and Caltanissetta Provinces).

- South-Eastern Metaphontics (Ragusa Province and southern Siracusa Province).

- Eastern non-metaphonic (central-septentrional area of Siracusa province and Catania province).

- Messinés (province of Messina).

- Pantheria Island, influenced by Arabic.

- Eoliano (archipelago of the Aolias Islands).

- Related to Sicilian are the other extreme southern Italian dialects:

- Calabrés centro-meridional (provincias de Reggio de Calabria, Vibo Valentia, Catanzaro and Centro-meridional area of the province of Cosenza) in Calabria.

- Salentino (in the province of Lecce, central-central area of the province of Brindisi and eastern part of the province of Tarento) in Apulia.

- Eight key dialects are distinguished in Sicily and nearby islands:

Balco-Romanian group

The Balco-Romanian languages or Romanian dialects have several notable distinctive features:

- The occlusive deaf intervocálicas of Latin origin /p, t, k/ are not sounding (rejoining with italorromances and the extinct Dalmatian).

- They do not palate the group -cl intervocálico (travel sharing with italorromances and the extinct Dalmatian).

- The groups -ps, -pt and the groups -ct, -gn evolve to -pt and -mn (share with the extinct Dalmatian).

- And form the plural of words by vowels - Yeah.. (draft shared with Dalmatian and several Italian Romance languages)

- The Latin phonemes ,/ they are confused in /o/ while in the rest of the Romance languages (except the Sardinian), the same Latin vowels are still distinguished by evolving to two different seals /*o/ and /*./.

Romanian (română; partial attestations in the 12th century, complete in the 15th century): language of the ancient Roman province of Dacia cut off from the rest of what is called Romania. The Slavic superstratum has relatively little relevance except in the lexicon, and Romanian asserts itself as a fairly conservative language. It is considered to have four dialects:

- Dacorrumano, usually called Romanian. It is the official language of Romania and Moldova and co-official language in Voivodina (Serbia). It is divided into:

- Moldavo, north.

- Valaco, south.

- Transylvania, west.

- Istrorrumano, spoken in Istria (in the process of extinction).

- Meglenorrumano (or Meglenita), spoken in North Macedonia and some villages in northern Greece

- Arrumano (or Macedonian), spoken mainly in Albania, Serbia, North Macedonia and Greece.

Several Romanian linguists, however, consider the last three varieties to be separate languages, since the Romanian language proper is only Dacor-Romanian (cf. "Spanish" vs. "Castilian, Astur-Leonese, Aragonese").

Dalmatian

Dalmatian, a dead language spoken in some coastal cities of Dalmatia (coast of present-day Croatia). It had two known dialects:

- Vegliota (veklisu)in the north, which was extinguished in 1898.

- Ragusano, in the south, disappeared in the 15th century.

The Dalmatic language was related to Romanian and other Romano-Balkan languages such as Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, and Istro-Romanian.

Poorly attested Romance languages

The romanization process occupied a larger area in Europe than is currently occupied by Romance languages in Europe, this is basically because in some territories, even in some intensely romanized ones such as North Africa, Latin or Romance The incipient language was later displaced by the languages of other peoples who settled in the region, displacing the local Romance languages. In most cases, the Romance languages spoken in these regions are poorly attested and are only known indirectly, basically from loans to other languages that displaced them. Among those languages are:

- The British romance

- The North African romance

- The Panonian romance

- The romance of the Moselle

Derived artificial languages

These languages try to retake Latin elements (Romance) trying to be neutral to all current Romance languages and even with other languages. The most common examples are: Esperanto, Ido, Interlingua (probably the best example of neutrality in the Romance languages), etc. There have also been exercises of linguistic uchrony for possible Neo-Latin languages that could have been generated if the Latinization of certain places had prospered, such as Brithenig or Wenedyk.

Creole languages

Several European countries had or have territories on other continents: America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. In these communities, in some cases these languages have given rise to new Latin-based creoles that fed on the original languages of the community that speak them. Among these are:

- French Criollo. Set of French-based Creoles, influenced by indigenous or African languages. Highlights, above all Créole Haitian, the Patois Antilles, or Bourbonnais of the Indian Ocean.

- Portuguese Criollo. Set of Creole languages whose basis is the Portuguese language. Examples: angolar (Angola), caboverdiano (Cabo Verde), lunguyê and lining (both in Sao Tome and Principe), indoportugués (ancient lus possessions in India), kriolu (Guinea Bisáu).

- Chadian languages of the Philippines. The Chavacano of Zamboanga and the Chabacano of Cavite (in extinction). These languages are suffering a strong decriollization since the 1970s, as there are almost no Spanish cult speakers in society that promote the maintenance of classical forms. Today it is estimated that they are 70% Spanish and 30% base malaya, being the base bisaya for Zamboanga and tagalo for Cavite.

- Papiamento (language of the island of Aruba). Although its root is Portuguese based, it receives a substantial amount of loans from the Dutch and its base with the passing of years becomes Spanish due to the similarity of Spanish and Portuguese, considering itself today a Spanish substrate cell with influence of the Dutch.

- Palenquero. It is spoken in San Basilio de Palenque, in Colombia, department of Bolivar, by the descendants of the hills who were freed from slavery. This language has a large substrate of ancient Portuguese for the months that kidnapped Africans had to pass on the ships of traffickers and a lexical base of Castilian, for the long permanence of their descendants in a region where Spanish speaking predominates. The linguistic testimony clearly shows that the African ancestors of the speakers of this language were mostly of Bantu origin.

- Judeo-Romantic languages. It refers to those dialects of Romance languages spoken by Jewish communities installed in some of these countries, and altered to such an extent that they obtained recognition as their own languages, joining the numerous group of Jewish languages. It is possible to count, among others, the Judeo-Spanish or Ladino, the Judeo-Portuguese, the French or zarphatic, the Judeo-Italian, the shuadit or Judeo-provenzal, etc.

Lexical comparison

The following table presents some examples to compare the phonetic evolution of words in the different Romance linguistic varieties.

| Latin (c) | Aragonese | asturleon | Catalan | French | Galician | Eonaviego | Italian | ligur (German) | Mozárabe | Lombard (milanes) | véneto | jersey | Portuguese | Provencal (Occitan) | Romanian | Sardinian | Spanish |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALTU(M) | High | Altu | alt | haut | High | High | High | èrto | ot High | alt volt | alt | haut | High | aut | înalt | Altu artu | High |

| RBOR(EM) | tree | tree treee | Anger | Anger | arbore | tree | Albero | èrbo | arbor | alber | albaro | bouais | arvore | Anger | arbore pom cupc | àrbore | tree |