Roman empire

The Roman Empire was the period of Roman civilization that followed the Republic and was characterized by an autocratic form of government. At its height it controlled territory stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the shores of the Caspian and Red Seas in the east, and from the Sahara desert in the south to the banks of the Rhine and Danube rivers and the Caledonian border in the north. Due to its extent and duration, Roman institutions and culture had a profound and lasting influence on the development of language, religion, architecture, literature, and law in the territory it ruled.

During the three centuries before the rise of Caesar Augustus, Rome went from being one of the many states of the Italian peninsula to unifying the entire region and expanding beyond its limits. During this republican stage, its main competitor was Carthage, whose expansion through the southern and western basin of the western Mediterranean rivaled that of Rome. The Republic gained undisputed control of the Mediterranean in the II century BCE. C., when he conquered Carthage and Greece.

Rome's domains became so extensive that the Senate became increasingly incapable of exercising authority outside the capital. Likewise, the empowerment of the army revealed the importance of having control over the troops to obtain political gains. This is how ambitious characters emerged whose main objective was power. This was the case with Julius Caesar, who not only expanded Rome's domain by conquering Gaul, but also challenged the authority of the Roman Senate.

The political system of the Empire arose out of the civil wars that followed the death of Julius Caesar. After the civil war that pitted him against Pompey and the Senate, Caesar seized absolute power and named himself dictator for life. In response, several members of the Senate orchestrated his assassination, which would mean the restoration of the Republic. The precedent was not lost on Caesar's nephew and adopted son Octavian, who became the first emperor years later after defeating the alliance between his former ally Mark Antony and Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII. Octavio maintained all the republican forms of government, but in practice he ruled as an autocrat. In 27 a. C. the Senate formally granted him supreme power, represented in his new title of Augustus, effectively making him the first Roman emperor.

The first two centuries of the Empire saw a period of unprecedented stability and prosperity known as the Pax Romana. However, the system built by Augustus collapsed during the Crisis of the 3rd century, a prolonged period of civil wars that began the period known as the Dominated, during which the government acquired a despotic character and more akin to an absolute monarchy. In the year 286, in an effort to stabilize the Empire, Diocletian divided the administration into a Greek East and a Latin West. By this point Rome had already ceased to be the capital of the Empire. The Empire was united and separated again on various occasions until, on the death of Theodosius I in 395, it was definitively divided in two.

Christians rose to positions of power after the Edict of Milan issued by Constantine I, the first Christian emperor, in 313. Later, the Period of the Great Migrations began, precipitating the decline of the Western Roman Empire. With the fall of Ravenna before Flavio Odoacer and the deposition of the usurper Romulus Augustulus in 476, the end of the Ancient Age and the beginning of the Middle Ages are traditionally marked, even when the consideration of Late Antiquity as a a period of transition between both periods.

The Eastern Roman Empire would continue for almost a millennium as the only Roman Empire, although it is usually given the historiographical name of the Byzantine Empire, until the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks of Mehmed II in 1453.

The legacy of Rome was immense, especially in Western Europe; so much so that there were several attempts to restore the Empire, at least in its name. Notable are the reconquest campaigns of the Emperor Justinian the Great in the VI century and the establishment of the Carolingian Empire by Charlemagne in the year 800., which would evolve into the Holy Roman Empire. However, none managed to reunify all the Mediterranean territories as Rome once did in classical times. According to certain periodizations, the fall of the Western and Eastern Empire marks the beginning and end of the Middle Ages.

In the immense territory of the Roman Empire many of the great and important cities of present-day Western Europe, North Africa, Anatolia and the Levant were founded. Examples are Paris (Lutecia), Istanbul (Constantinople), Vienna (Vindobona), Zaragoza (Caesaraugusta), Mérida (Augusta Emerita), Milan (Mediolanum), London (Londinium), Colchester (Camulodunum) or Lyon (Lugdunum) among others.

History

Roman expansion began in the VI century BC. C. shortly after the founding of the republic. However, it was not until the III century BCE. C. that Rome began with the annexation of the provinces, that is, the territories located outside the Italian peninsula. At that time, and four centuries before reaching its greatest territorial extension, Rome and its domains already constituted an "empire"., although its system of government continued to be that of a republic. The Roman Republic was not a state in the contemporary sense of the term, but rather a network of cities, each with a different degree of autonomy in relation to the Roman Senate. The provinces were administered by consuls and praetors, who were elected to serve a one-year term. The consuls' military power was based on the legal notion of imperium or military command. triumphant consuls were bestowed the title of imperator, from which the term "emperor" derives.

August and the transition from the Republic to the Empire

Since the late II century a. C., Rome suffered a series of social conflicts, conspiracies and civil wars, while consolidating its influence beyond the Italian peninsula. The century I a. C. was marked by a period of instability formed by a series of both military and political revolts that paved the way for the implementation of an imperial regime. In the year 44 B.C. In BC, Julius Caesar was proclaimed perpetual dictator before being assassinated. A year later, Octavian, Caesar's great-nephew and adopted son, and one of the leading republican generals, became one of the members of the Second Triumvirate — a political alliance with Lepidus and Marco Antonio. After the Battle of Philippi in 42 B.C. C., the relationship between Octavio and Marco Antonio began to deteriorate, which led to the dissolution of the triumvirate and a war between the two. This ended with the battle of Actium, in which Marco Antonio and his beloved Cleopatra were defeated. The subsequent confrontation in Alexandria in 30 B.C. C. supposed the annexation of Ptolemaic Egypt by Octavio.

Principality

In 27 B.C. C, the Senate and the Roman people proclaimed Octavio princeps (first citizen) and granted him the power of proconsular imperium and the title of Augustus. This event began the period known as the Principate, the first epoch of the imperial period, which lasted from 27 B.C. C. and 284. The government of Augustus put an end to a century full of civil wars and began an era of social and economic stability known as the Pax Romana (Roman peace), which was promulgated during the next two centuries. Revolts in the provinces were infrequent and were quickly put down. As the sole ruler of Rome, Augustus was able to carry out a series of large-scale military, political, and economic reforms. The Senate gave him the power to appoint his own senators and authority over provincial governors, creating de facto the position that would later be called emperor.

Augustus implemented the principles of dynastic succession, so he was succeeded in the Julio-Claudian dynasty by Tiberius (r. 14-37), Caligula (r. 37-41), Claudius (r. 41-54) and Nero (r. 54-68). The latter's suicide led to a brief period of civil war known as the year of the four emperors, which ended with the victory of Vespasian (r. 69-79) and the founding of the short-lived Flavian dynasty, remembered for being responsible of the construction of the Colosseum in Rome. This was succeeded by the Antonine dynasty, which included the emperors Nerva (r. 96-98), Trajan (r. 98-117), Hadrian (r. 117-138), Antoninus Pius (r. 138-161) and Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180), the so-called "five good emperors." In 212, through the Edict of Caracalla promulgated by the homonymous emperor (r. 211-217), Roman citizenship was granted to all free citizens of the Empire. However, and despite this universal gesture, the Severan dynasty was marked by several revolts and disasters throughout the crisis of the third century, a time of invasions, social unrest, economic difficulties and plague. In periodization, this crisis is generally considered the moment of the transition from Classical Antiquity to Late Antiquity.

Dominated

Diocletian (r. 284-305) resigned as princeps and adopted the title of dominus (master or lord), marking the transition from Principality to Dominated—a state of absolute monarchy that lasted from 284 until the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476—Diocletian prevented the collapse of the empire, although his reign was marked by persecution of Christianity. During his rule, a tetrarchy was established and the empire was divided into four regions, each ruled by a different emperor. In 313, the tetrarchy collapsed and, after a series of civil wars, Constantine I (r. 306-337) emerged as sole emperor. This was the first emperor to convert to Christianity and established Constantinople as the capital of the Eastern Empire. Throughout the Constantinian and Valentinian dynasties, the empire was divided into a western and an eastern half and power was shared between Rome and Constantinople. The succession of Christian emperors was briefly interrupted by Julian (r. 361-363) by attempting to restore traditional religion in his own way. Theodosius (r. 378-395) was the last emperor to rule the empire as a whole, he died in 395, after Christianity was declared the empire's official religion.

Fragmentation and decline

Starting in the 5th century, the Roman Empire began to fragment as a result of migrations, which outnumbered the the empire's ability to assimilate migrants. Although the Roman army was able to repel the invaders, most notably Attila the Hun (r. 434-453; who was Romanised), it had assimilated so many peoples of dubious loyalty that the Empire began to fall apart. Most historians date the fall of the Western Roman Empire to 476, the year in which the usurper Romulus Augustulus (r. 475-476) was overthrown by Flavius Odoacer (r. 476-493). However, in Instead of assuming the title of emperor, Odoacer reinstated Julius Nepos and swore allegiance to Flavius Zeno, rewarding him with the titles of dux Italiae (duke of Italy) and patrician. Over the next century, the eastern empire, known today as the Byzantine Empire, gradually lost control of the western part. The Byzantine Empire ceased in 1453 with the death of Constantine XI (r. 1449-1453) and the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire.

Geography and demography

The Roman Empire was one of the greatest in history. It ruled a continuous stretch of land across Europe, North Africa, and the Near East, from Hadrian's Wall in rainy England to the sunny shores of the Euphrates River in Syria, from the fertile plains of Central Europe to the lush banks of the Nile valley in Egypt. The notion of imperium sine fine (empire without end) manifested the Roman ideology that their empire was not limited in space and time. Most of the expansion Roman rule took place during the republic, although some territories in northern and central Europe were not conquered until the I century.. C., a period that corresponded to the consolidation of Roman power in the provinces. of towns in the regions of the empire. The imperial administration conducted frequent censuses and kept meticulous geographical records.

The empire reached its greatest territorial extent during the reign of Trajan (r. 98-117), corresponding to an area of approximately five million square kilometers and currently divided into forty countries. Traditionally, the population was estimated to be during this period it reached between fifty-five and sixty million inhabitants, which would come to be between a sixth and a quarter of the world's population and the largest number of inhabitants of any political unit in the West until the middle of the century XIX. However, more recent studies estimated that the population could have reached between seventy and one hundred million inhabitants. The empire's three largest cities—Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch—were twice the size of any European city until the early 17th century. Adriano, it happened or of Trajan, he abandoned the expansionist policy and opted for one of consolidation of the territory, so he defended, fortified and patrolled the border regions.

Language

The languages of the Romans were Latin, which Virgil highlighted as a source of Roman unity and tradition. Although Latin was the main language in the courts and public administration of the Western Empire and the army throughout the empire, it was not it was officially imposed on peoples under Roman rule. When conquering new territories, the Romans preserved local traditions and languages and gradually introduced Latin through public administration and official documents. This policy contrasts with that of Alexander Magnus, who made Hellenistic Greek the official language of his empire. This made Ancient Greek the lingua franca of the eastern half of the Roman Empire, throughout the eastern Mediterranean and Asia Minor. In the West, Greek Vulgar Latin gradually replaced Celtic and Italic languages, both with the same Indo-European roots, facilitating their adoption.

Although the Julio-Claudian emperors encouraged the use of Latin in the conduct of official business throughout the empire, Greek remained the literary language among the Roman cultural elite and was fluently spoken by most rulers. Claudius attempted to limit the use of Greek, even revoking citizenship to those who did not know Latin, although the Senate itself had native Greek ambassadors. In the Eastern Empire, laws and official documents were regularly translated from Latin into Greek. The simultaneous use of both languages can be seen in bilingual inscriptions composed of the two languages. In 212, when citizenship was granted to all freemen in the empire, citizens who did not know Latin were expected to acquire some basic notions of Latin. language. In the early V century, Justinian I strove to promote Latin as the language of law in the East, though he lost gradually its influence and existence as a living language.

The constant reference to interpreters in literature and official documents indicates the vulgarity and prevalence in the Roman Empire of a large number of local languages. Roman jurists themselves were concerned with ensuring that laws and oaths were correctly translated and understood in local languages, such as Punic, Gaulish, Aramaic, or even Coptic, predominant in Egypt, or Germanic languages, influential in Rhine and Danube regions. In some regions, such as the province of Africa, Punic was used on coins and inscriptions on public buildings, some bilingual alongside Latin. However, the latter's hegemony among elites and as the official language of written documents compromised the continuity of various local languages, as all cultures within the empire were predominantly oral.

Roman army

The supreme command of the army corresponded to the Emperor. Outside of Italy, in the provincial territories, the command corresponded to the provincial governor (but this in turn was subject to the Emperor who could remove it whenever he wanted), and the Emperor could also assume it temporarily. The number of legions fluctuated throughout the imperial era, with a maximum number close to thirty.

The upper classes of knights and senators were disappearing from the army, so that the legions had to be recruited among the citizens, first in Italy and later progressively in the provinces where they were stationed (the Mauri, the Thracians and above all the Illyrians stood out), so that from Hadrian the recruitment was done almost exclusively in the provinces where the legion served, and finally foreign mercenaries (especially Germans) were used. With the entry of the proletarians, the army became professional, although these soldiers had an easier time mutinying and looting. Promotions were earned by merit, by favors, or by money. The time of service was progressively increased and services of thirty or more years were not exceptional, after which an economic stipend, citizenship and privileges such as access to some municipal positions were obtained.

The legion had arsenals (weapons) and manufacturing and repair workshops. The soldiers received a salary, imperial donations on the occasion of accession to the throne, festivals or riots, gifts (stillaturae ) and the spoils of war. The daily food ration grew and was provided with wheat, salt, wine, vinegar, fresh meat and salted meat.

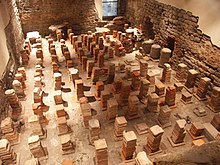

Camps became strongholds. They had walls and towers and were divided internally into four parts marked by two perpendicular pathways. They contained a bathroom, a meeting room, chapels, offices, a jail, a hospital, and warehouses. Merchants, artists, prostitutes and others flocked to its surroundings and established themselves, constituting urban agglomerations, and outer neighborhoods for the civilian population (canabae) grew with bathhouses, amphitheaters and other public buildings. The nearby land was used as pasture for cattle, which was leased to farmers in the area.

Legion Structure

A typical Roman legion (whose emblem was a silver eagle) consisted of ten cohorts (with their respective banners) each of them with five or six centuries of eighty men subdivided into ten conspiracies (basic unit of eight legionaries who shared a tent), counting therefore each legion five or six thousand infantry men, divided into fifty or sixty centuries. It also had the regular auxiliary and cavalry guerrillas (alae) with one hundred and twenty cavalry men.

The emperor and in his name the provincial governor appointed the legatus legionis, lieutenants of the legion with the functions of praetor, and their assistants the military tribunes and centurions.

Along with the Legion's legates were the benefiaciarii (in charge of trusted missions), the strato (squires), the commentarienses (archivists), the cornicularii (accountants) and the actuary (clerks). The military tribunes were divided into laticlavii (affected to the administration) and angusticlavii (properly military missions). The centurions were the basic officers of the infantry (the century of 80 men) and the cavalry (the turma of 30 men). Each century and turma had a non-commissioned officer called optio (equivalent to sergeant), who also performed administrative functions. The decurions were non-commissioned officers who commanded a decuria (nine men) in the infantry and commanded a squadron or turma (30 horsemen) in the cavalry of the auxiliary units. Other non-commissioned officers were the tesserarius (equivalent to a sergeant), the signifer or vexillarius (standard bearer), the aquilifer (the bearer of the legionary eagle), the campiductor (instructor) and the pecunarius (furriel).

Cohorts

The cohorts were structured in ten rows of 40 or 60 rows that in Trajan's time were reduced to five rows. With Hadrian the family cohort arose (composed of 1200 chosen soldiers) while the remaining cohorts were called quingentaries and numbered 500 soldiers.

Several specialized cohorts were structured: infantry (peditata), cavalry or mixed (equitable), police (togata), surveillance (excubitoria), the garrison in a city (urban), the one in charge of putting out fires (Vigilio) and the one in charge of imperial guard and custody or of a warlord (Praetorian ). This personal guard of the general in chief was common in the Empire. There was the headquarters (Praetorian Guard or guard of the general in chief) the members had more salary and were exempt from the work of the camp, and they became the arbitrators of the Empire.

The Centuries

The centuries were commanded by centurions (the most prestigious centurion was the primus pilus usually the most senior), above which were six tribunes of the legion of equestrian rank, and the legatus of the legion, of senatorial rank, who had previously been praetor (in provinces where there was only one legion, the legatus of the province and that of the Legion were the same person).

Equipment

The equipment of the legionnaires changed substantially depending on the rank. During campaigns, legionnaires were equipped with armor (lorica segmentata), shield (scutum), helmet (galae), a heavy spear and a light (pilum), a short sword (gladius), a dagger (pugio), a pair of sandals (caligae), a sarcina (walking backpack), and food and water for two weeks, kitchen equipment, two stakes (Sude murale) for the construction of walls, and a shovel or basket.

Roman Army

The Roman Navy (Latin classis, literally fleet) comprised the naval forces of the ancient Roman state. Despite playing a decisive role in Roman expansion across the Mediterranean, the navy never had the prestige of the Roman legions. Throughout their history, the Romans were an essentially terrestrial people, and they left nautical issues in the hands of peoples more familiar with them, such as the Greeks and Egyptians, to build ships and command them. Partly because of this, the navy was never fully embraced by the Roman state, and was considered "non-Roman". In antiquity, navies and trade fleets did not have the logistical autonomy that they do today. Unlike modern naval forces, the Roman navy, even in its heyday, did not exist autonomously, but rather operated as an adjunct to the Roman Army.

During the course of the First Punic War the navy was massively expanded and played a vital role in the Roman victory and the rise of the Roman Republic to hegemony in the Mediterranean. During the first half of the II century B.C. C. Rome destroyed Carthage and subjugated the Hellenistic kingdoms of the eastern Mediterranean, achieving complete control of all the shores of the inland sea, which they called Mare Nostrum. Roman fleets once again played a leading role in the I century BCE. C. in the wars against the pirates and in the civil wars that caused the fall of the Republic, whose campaigns extended throughout the Mediterranean. In 31 B.C. C. the battle of Actium put an end to the civil wars with the final victory of Augustus and the establishment of the Roman Empire.

During the imperial period the Mediterranean was a peaceful "Roman lake" in the absence of a maritime rival, and the navy was largely reduced to patrol and transport duties.

However, on the borders of the Empire, in the new conquests or, increasingly, in the defense against barbarian invasions, the Roman fleets were fully involved. The decline of the Empire in the III century d. C. felt in the navy, which was reduced to the shadow of itself, both in size and in combat capacity. In the successive waves of barbarian peoples against the borders of the Empire, the navy could only play a secondary role. At the beginning of the v century the borders of the empire were breached and barbarian kingdoms soon appeared on the shores of the western Mediterranean. One of them, the Vandal people, created a fleet of their own and attacked the shores of the Mediterranean, even going so far as to sack Rome, while the dwindling Roman fleets were unable to offer resistance. The Western Roman Empire collapsed in the v century and the subsequent Roman army of the enduring Eastern Roman Empire is called by historians Byzantine Navy.

Economy

The Empire's economy was based on a network of regional economies, in which the state intervened and regulated trade to ensure its own revenue. Territorial expansion allowed land use to be reorganized, leading to the production of agricultural surpluses and a progressive division of labour, particularly in North Africa. Some cities defined themselves as the main regional centers of a certain industry or commercial activity. The scale of the buildings in the urban areas indicated a fully developed construction industry. Papyrus documents demonstrate complex accounting methods that suggest elements of economic rationalism in a highly monetized economy. During the first centuries of the Empire, road and transportation networks expanded significantly, rapidly uniting regional economies. Economic growth, although not comparable to that of modern economies, was higher than that of most pre-industrialization societies.

Currency and Banking

The economy of the Empire was universally monetized. The normalization of money and forms of payment promoted commercial and economic integration in the provinces. Until the IV century, the basic monetary unit was the sestertius, although at the beginning of the Severe dynasty the sestertius was also used. silver denarius, worth four sesterces. The lowest value common currency was the bronze as, worth one quarter sestertius. The bullion was not considered currency and was used only in businesses in the border regions. The Romans of the I and II counted the coins rather than weighing them, indicating that the value was attributed according to their fiat value, and not the value of the metal.

Rome had no central bank, so regulation of the banking system was minimal. Bank reserves in classical antiquity were generally less than total customer deposits. Most banks had only one branch, although some of the largest had as many as fifteen branches. A commercial banker named argentarius received and held deposits for an indefinite or fixed term, also making loans to third parties. An individual with debt could use it as a form of payment, transferring it to another party and without any change of money. The banking system was present in all regions and allowed large amounts of money to be exchanged anywhere without the need for physical currency transfers, which reduced the risk associated with transportation. At least one credit crunch in the Empire is known to have occurred in AD 33, during which the central government intervened in the market with a financial bailout (mensae) of 100 million sesterces.

The government did not borrow money: in the absence of public debt, the deficit had to be financed with monetary reserves. During the crisis of the third century, the decline of long-distance trade, the interruption of mining, and the transfer Securities abroad by the invaders significantly reduced money in circulation. The Emperors of the Antonine and Severe dynasties drastically devalued the currency, particularly the denarius, due to pressure with paying the military. The sudden inflation during the reign of Comodo (r. 180-192) he put the credit market at risk. Although Roman currency always had a fiat value, during the reign of Aurelian (r. 270-275) the economic crisis reached its peak, causing bankers to lose confidence in money issued by the central government. Diocletian (r. 286-305) implemented several monetary reforms and introduced the gold solid, but the credit market never recovered its former strength.

Transportation and communications

The Romans favored the transport of goods by sea or river, since transport by land was more difficult.. Roman sailing ships sailed not only the Mediterranean (Mare Nostrum), but also all the major rivers of the empire, including the Guadalquivir, Ebro, Rhone, Rhine, Tiber, and Nile.

Land transportation made use of a complex and advanced network of Roman roads. Taxes in kind paid by local communities required frequent travel by administrative officials, animals, and public course vehicles (Cursus publicus, the state postal and transportation system implemented by Augustus). The first via , the Appian Way, was created in 312 BC. C. by Appius Claudius the Blind, to unite Rome with the city of Capua. As the empire expanded, the administration adapted the same scheme in provinces. At its height, the Roman road network had up to 400,000 km of roads, 80,500 of which were paved.

Every seven or twelve Roman miles there was a mansio, a service station for civil servants maintained by the State. Among the employees of these positions were drivers, secretaries, blacksmiths, veterinarians and some soldiers. The distance between manors was determined by how far a wagon could travel in the course of a day, and some could grow into small towns or trading warehouses. In addition to the manor, some taverns offered lodging, animal feed, and eventually, prostitution services. The most common animals of transport were mules, which traveled at a speed of four miles per hour. To get an idea of communication time, a courier needed nine days to travel between Rome and Mogontiacum, in the province of Germania Superior. The paths were marked by milestones placed at intervals of about a thousand paces (1,480 metres).

Society

The Roman Empire was a multicultural society, with a surprising capacity for cohesion capable of creating a sense of common identity by assimilating the most diverse peoples. The Roman concern for the creation of monuments and community spaces open to the public, such as forums, amphitheatres, circuses or spas, helped to establish the feeling of common "Romanity". Although Roman society had a complex system of hierarchies, this is hardly compatible with the modern concept of "social class".

The two decades of civil war leading up to Augustus' rule left traditional Roman society in a state of confusion and upheaval. However, the dilution of the republic's rigid hierarchy led to increased social mobility among the Romans, both up and down, and more expressive than in any other documented ancient society. Women and slaves were given opportunities previously denied them. Social life in the Empire, particularly for those with limited resources, was further fueled by the proliferation of voluntary associations and brotherhoods (collegia and sodalitates) formed for various purposes: professional and trade guilds, veterans' groups, religious associations, gastronomic clubs and artistic companies. Under Nero's rule it was not uncommon for a slave to be wealthier than a freeborn citizen, or an equestrian more influential than a senator.

Citizenship

According to the jurist Gaius, the main distinction between persons in Roman law was between free citizens (liberi) and slaves (servi). free citizens could still be specified based on their citizenship. During the early empire, only a limited number of men had full rights to Roman citizenship, which allowed them to vote, stand for election, and be ordained as priests. Most citizens had only limited rights, but were entitled to legal protection and other privileges that were prohibited to those without citizenship. Free men who lived within the empire, but were not considered citizens, had the status of peregrinus, who were considered "non-Romans". In 212, through the Edict of Caracalla, the emperor extended the right of citizenship to all the inhabitants of the empire, repealing all laws that distinguished citizens from non-citizens.

Slaves

In the time of Augustus, about 35% of the residents of Italy were slaves. Slavery was a complex and economically useful institution that underpinned the Roman social structure, since industry and agriculture depended on it. In the cities, slaves could pursue a variety of professions, including teachers, doctors, cooks, and accountants, though most performed only low-skilled tasks. Outside of Italy, slaves constituted on average 10–20% of the population. Although slavery declined in the III and IV, remained an integral part of Roman society until the V, gradually disappearing over the VI and VII. This occurred in parallel with the decline of urban centers and the disintegration of the complex economic system.

Roman slavery was not based on racial discrimination. During the republican expansion, a period in which slavery became widespread, the main source of slaves were prisoners of war of the most diverse ethnic groups. The conquest of Greece brought large numbers of extremely skilled and educated slaves to Rome. Slaves could also be sold in markets and occasionally by pirates. Other sources of slavery included the abandonment of children and self-enslavement among the poorest. Vernas (vernae) were slaves born to a slave mother who were born and raised in the home of their owners.. Although they did not have any particular legal protection, the owner who mistreated or did not take care of his property was frowned upon by society, since they were considered part of his family , and could even be the children of the free men of the family.

Slavery law is quite complex. Under Roman law, slaves were considered property and had no legal personality. A slave may be subjected to forms of corporal punishment prohibited to citizens, such as sexual exploitation, torture, and execution. In legal terms, a slave cannot "be raped" since rape can only be done on free people; the rapist of a slave would have to be charged by the owner for material damages. Slaves did not have the right to marry, although unions were sometimes recognized and they could marry if both were freed. Technically, a slave could not own property, although a slave doing business could have access to an individual fund or account (peculium), which he could dispose of freely. The terms of this varied according to the relationship of trust between the owner and the slave. A slave with a business aptitude could have considerable autonomy in managing businesses and other slaves. Within a residence or workshop, it was common to have a hierarchy among slaves, with one slave leading the rest. Successful slaves could accumulate enough money to buy their freedom or be released for services rendered. Manumission (liberation of slaves) became so common that, in the II century B.C. C., a law limited the number of slaves that an owner could free.

In the aftermath of the Servile Wars (131-71 BC), legislation attempted to lessen the threat of slave rebellions by limiting the size of labor groups and harassing runaways. Over the centuries, slaves gained increasing legal protection, including the right to bring charges against their masters. A purchase contract could prevent the provision of a slave, as most male and female prostitutes were slaves. The growth of the eunuch slave trade in the late 20th century I promoted legislation prohibiting the castration of a slave against his will.

Freedmen

Unlike the Greek polis, Rome allowed freed slaves to become citizens, even having the right to vote. A slave who obtained freedoms was called a freedman (libertus; "liberated person") in relation to his former master, who later became his patron (patronus). However, the two parties continued to have legal obligations to each other. The social class of freedmen became known as "libertines" (libertini), although later the terms liberto and libertine (libertinus) were used interchangeably. A libertine could not to hold positions in the public administration or in the state priesthood, although he could exercise the priesthood in the imperial cult. Neither could a freedman marry or be part of a family of the senatorial order, although during the early empire freedmen held important positions in the administration.

Orders

In the context of the Roman Empire, an order (ordo; plural ordine) means an aristocratic class. One of the purposes of the censuses was to determine the order to which a particular person belonged. In Rome, the two orders with the highest status were the senatorial order (ordo senatorius) and the equestrian order (ordo equester). Outside Rome, the decurions (ordo decurionum) represented the local aristocracy. The position of "senator" was not an elective position. A citizen was admitted to the Senate after being elected and having served for at least one term as a magistrate. A senator must also have a wealth of at least one million sesterces. Not all men who met the criteria for the senatorial order accepted a seat in the Senate, which required domicile in Rome. Since the Senate consisted of 600 seats, the emperors used to fill the vacant seats by direct appointment.A senator's son belonged rightfully to the order of the Senate, although he had to qualify on his own merits to be admitted to the Senate. Senators could be expelled for violating the rules of moral conduct; for example, they could not marry a freedwoman or fight in the arena. In Nero's time, senators came mainly from Rome and other parts of Italy, with other groups coming from the Iberian peninsula and southern France. During Vespasian's rule, senators from the eastern provinces began to join them. During the Severe dynasty, Italics already made up less than half of the senate.

The office of Roman senator was the highest office and was considered the culmination of the political course (cursus publicus). However, members of the equestrian order in many cases had greater wealth and power. Admission to the order was based on a person's wealth and possessions, qualified by a census valuation of 400,000 sesterces and at least three generations of free births. The eques progressed throughout of a military career (tres militiae) with the aim of becoming prefects and prosecutors of the imperial administration.

The integration into the orders of men from the provinces reveals the social mobility that existed during the early empire. The Roman aristocracy was based on competition, and unlike later European nobility, a Roman family could not maintain its status through title or land inheritance alone. Admission to higher orders brought with it more than just privileges. and prestige, but also a series of responsibilities. Maintaining the status required large personal expenses, since the financing of public works, events and services in Roman cities depended on their most prominent citizens and not on the taxes collected, which were mainly destined to finance the army.

Women

During the Republic and Empire, free Roman women were considered citizens and, although there was no women's suffrage, they managed to hold political office and even serve in the military. Roman women kept their maiden name for all his life. Children most often chose to receive their father's surname, although in imperial times they were also able to keep their mother's. Roman women could own property, enter into contracts, and do business, including manufacturing, shipping, and bank loans. It was common for women to finance public works, indicating that many of them owned or managed considerable fortunes. Women had the same rights as men regarding inheritance without the father's will. The right to own and manage property, including to the terms of their own will, provided Roman women with enormous influence over their children, even into adulthood.

Marriage

The archaic form of marriage cum manum, whereby the woman was subject to the authority of her husband, fell out of favor during the imperial period. A married Roman woman remained the owner of the property that she brought to the wedding. Technically, even after moving into her husband's residence, she was still under her father's authority, and only when the father died was she legally emancipated. This principle demonstrates the relative degree of independence of Roman women compared to with other cultures from ancient times to modern times. Although the Roman woman had to answer to her father in legal matters, she was free to manage daily life and her husband had no legal power over her. Although she was a a matter of social pride having married only once, the social stigma regarding divorce or remarriage was practically non-existent.

Religion

After the republican crisis and transition to empire, the state religion was adapted to support the new regime. Augustus implemented a vast program of revival and religious reforms. The public votes, which before asked the divinities for the safety of the republic, now had as their objective the well-being of the emperor. The cult of personality vulgarized the practices of veneration of ancestors and genius, the tutelary divinity of each individual. It was possible for the emperor himself to become a state deity while he was still alive through a vote in the Senate. The imperial cult, influenced by Hellenistic religion, became one of the main ways that Rome announced its presence in the provinces, cultivating loyalty and sharing the same cultural identity throughout the empire.

Roman religion

Religion in Ancient Rome encompasses not only the practices and beliefs that the Romans saw as their own, but also the various cults imported to Rome and the cults practiced in the provinces. The Romans saw themselves as deeply religious, attributing their economic and military prosperity to good relationship with the gods (pax deorum). The archaic religion believed to have been instituted by the first kings of Rome provided the foundations of me los maiorum, or "tradition", the basic social code of Roman identity. There was no separate Church. -State, so that religious positions in the State were filled by the same people who held positions in the public administration. During the imperial period, the highest pontiff was the emperor himself.

Roman religion was practical and contractual, based on the principle of do ut des ("I give you what you can offer"). Religion had as its principles the knowledge and correct practice of prayer, rituals and sacrifice, and not that of faith or dogma. For the common citizen, religion was part of daily life. Most of the residences had a domestic altar in which prayer and libation were performed. Cities were decorated by neighborhood altars and places considered sacred, such as water springs and caves, and it was common for people to make a vow or offer some fruit when they passed a place of worship. The Roman calendar was organized according to of religious commemorations. During the imperial period, there were 135 days of the year dedicated to religious festivities and games (ludi).

One of the main characteristics of Roman religion was the large number of deities worshiped and the parallel reverence of Roman deities with local deities. The policy of Roman conquest consisted in the assimilation of deities and cults of the conquered peoples, not their eradication. Rome promoted stability among different peoples by supporting different religious heritages, building temples to local deities that framed indigenous practices in the hierarchy of Roman religion. At the height of the empire, the International deities were worshiped in Rome, whose worship had spread to the remotest provinces, including Cybele, Isis, Epona, and the gods of solar monism, such as Mithras and Undefeated Sol.

Mystery religions, which offered initiates salvation after death, were practiced in a complementary way to family rituals and participation in public religion. However, the mysteries involved secrecy and exclusive oaths, which Roman conservatives viewed with suspicion and as characteristic elements of magic, conspiracy, and subversive activity. Various attempts were made to suppress sects that seemed to threaten traditional unity and morale, some of them violently. In Gaul, several attempts were made to check the power of the druids, initially by banning Roman citizens from belonging to the order, and later by outlawing druidism altogether. However, the Celtic traditions themselves were reinterpreted in the context of imperial theology, giving rise to Gallo-Roman culture.

Solar Monism

As the Empire declined, the mystery religions gained strength while the traditional ones declined. Among the new religions, Mithraism arose, which gained weight in the military establishment until it was introduced into the court by soldier-emperors such as Aureliano; To this we must add that from the traditional Roman religion itself and by the hand of philosophers such as the Neoplatonists (such as Plotinus), the monotheistic idea was gaining strength, seeing the Sun (similar to what happened in the time of Akhenaten) as the being or power original from which the rest of the gods came, these being avatars of the first. This syncretization process allowed a natural transition to Christianity, contrary to the unpopular belief of its imposition by force.

Christianization

The monotheistic rigor of Judaism posed difficulties for the Roman policy of religious tolerance. When political and religious conflicts became irreconcilable, various revolts broke out between Jews and Romans. The siege of Jerusalem in AD 70 led to the sacking of the city's temple and the dispersal of Jewish political power. Christianity arose in the province of Judea in the II as a Jewish religious sect, with Pope Linus in 76 AD playing a major role in that period. The religion gradually spread to Jerusalem, initially establishing major centers in Antioch and Alexandria, and from there throughout the empire. Official persecutions were few and sporadic and most of the martyrdoms occurred at the initiative of the local authorities.

At the beginning of the IV century, Constantine I with the edict of Milan legalized Christianity, being baptized shortly before he died, becoming the first Christian emperor, ushering in an era of Christian hegemony. The Emperor Julian made a brief attempt to revive traditional religion in his own way, but this was short-lived. In 391, Theodosius I the Great made Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire, permanently excluding all others. From the II century onwards, the Church Fathers began to condemn the remaining religious practices, collectively calling them "pagan". At the same time, calls for religious tolerance by traditionalists were rejected, and Christian monotheism became a feature of imperial rule. All heretics and non-Christians could be persecuted or excluded from public life. However, Christian practices have been influenced by much of the Roman religious hierarchy and by many aspects of Roman rituals, and many of these practices still survive through local Christian festivals and traditions.

Culture

The network of cities throughout the imperial territory (colonies, municipalities, or polis) was a cohesive element that fostered the Pax Romana. Early Empire were encouraged by Imperial propaganda to respect and enjoy peacetime values. Even the polemicist Tertullian stated that the II century was more orderly and educated than in previous times: «Everywhere there are houses, everywhere there are people, everywhere there are res publicas, cause of the people, there is life everywhere ». Many of the features associated with imperial culture, such as public worship, games and festivities, contests for artists, speakers and athletes, as well as the vast majority of works of art and public buildings, were financed by private individuals, whose expenses of the community benefit helped justify their economic power and legal and provincial privileges. The d The decline of cities and civic life in the IV century, when the wealthy classes could no longer finance public works, was one of the signs of the imminent dissolution of the empire.

Life in the cities

In classical antiquity, cities were considered territories that fostered civilization if they were properly designed, arranged, and adorned. Roman city planning and urban lifestyle were influenced by the Greek civilization of earlier periods. In the eastern part of the empire, Roman rule accelerated the development of cities that already had a markedly Hellenistic character. Some cities, such as Athens, Aphrodisias, Ephesus, and Gerasa, modified some aspects of architecture and urban planning in accordance with imperial canons, while expressing their individual identity and regional prominence. In the westernmost parts of the empire, Inhabited by Celtic-speaking people, Rome encouraged the development of planned urban centers, equipped with temples, forums, monumental fountains, and amphitheatres. These new cities were often designed in the vicinity of or on the site of pre-existing walled settlements (opidos). Urbanization in North Africa has expanded Greek and Punic cities along the coast.

Augustus carried out a vast building program in Rome that served as a model for the rest of the empire's cities, financing public works of art that expressed the new imperial ideology and reorganizing the city into neighborhoods (vicos; vici) administered at the local level, with a police and fire service. equestrian and physical exercise for young people. The Altar of Peace (Ara Pacis) and the Montecitorio obelisk, imported from Egypt, were built there, forming the pointer (gnomon) of a monumental sundial. Endowed with public gardens, the Field of Mars has become one of the main attractions of Rome.

The Romans pioneered the engineering and construction of sophisticated infrastructure such as plumbing, aqueducts, roads, and bridges. Works spanned the entire empire, made possible in large part by the extensive road network. In addition to environmental sanitation, infrastructure included facilities such as spas, forums, theatres, amphitheatres, and monuments. Aqueducts built throughout the empire supplied drinking water to farms and cities. The flow was generally with a free surface, presenting a minimum slope so that the water could flow, and they were built in masonry. The crossing of valleys was carried out on arched structures. In addition to this, they had the help of hydraulic pumps. The wastewater was collected in a sophisticated sewer network, an example of which is the Maximum Sewer in Rome, one of the oldest sewer networks in the world, built in Rome at the end of the VI a. C., initiated by Tarquínio Prisco, who took advantage of the experience developed by Etruscan engineering to drain wastewater into the Tiber river. The operation of the cloaca Maxima and other Roman sewer networks, such as the one at Eboraco (present-day York, England) continued for quite some time after the fall of the Roman Empire.

Housing

In the city of Rome, most of the population lived in multi-story apartment buildings (insulas), which offered very little fire safety. Public facilities, such as thermal baths, sanitary facilities (latrinae) and drinking fountains, as well as mass entertainment, they were mainly intended for the common people who lived on the island.

Wealthy families in Rome generally owned two or more dwellings: an urban dwelling (domus) and at least one country house (vila) in the province. The Domus was a private single-family home that could include private spas. Although some of Rome's neighborhoods had a high concentration of wealthy households, the upper classes did not live in segregated enclaves and wanted their homes to be visible and accessible to the population. The atrium was the reception space, in which the head of the family (pater familias) received clients and visitors each morning, from equally wealthy friends to needy dependents receiving alms. It was also the scene of rituals family religious, in which images of their ancestors and homesteads were present. Urban dwellings were generally located on busy public thoroughfares, so the ground floor facing the street was often rented to shops (taverns; tabernae). In addition to a small orchard, domus usually had a formal garden framed by a peristyle.

On the other hand, the town corresponded to an escape from the urban bustle, portrayed in literature as a symbol of a lifestyle that balances appreciation for art and culture with appreciation for nature and the agricultural cycle. The villages were generally located in centers of agricultural production or in seaside resorts along the coast. Ideally, they would have a view over the surrounding region, carefully framed by the architectural design. The interior of the dwellings was often decorated with paintings of gardens, fountains, landscapes, plant motifs, and animals, particularly birds and marine species, they were portrayed with such precision that contemporary archaeologists are sometimes able to identify the species.

Hot springs

Public baths had a hygienic, social and cultural function. The public baths were the center of daily socialization after work, in the evening before dinner, and were open to both men and women. The spa tradition is related to the cult of the Greek goddess Hygia (or Salus, its Roman equivalent) and Panacea, daughters of Aesculapius, goddesses of health and cleanliness, and with the recommendations of Hippocratic medicine. The oldest known Roman baths date from the 5th century BCE. C. in Delos and Olympia, although the best known are the baths of Caracalla. The development of aqueducts allowed the widespread construction throughout the imperial territory of thermal spas, large public thermal complexes, and spas, small spas, public or private.

The Roman baths had services that ensured body hygiene and hydrotherapy. The different rooms offered community baths at three different temperatures, which could be complemented with different services, such as exercise and training rooms, saunas, exfoliation spas (in which oils were massaged into the skin and a strigil was used), a playground or an outdoor swimming pool. Thermal baths were heated by hypocausts, the floor being based on ducts through which hot air circulated. Although some spas offered segregated facilities for men and women, mixed nude bathing between the sexes was relatively common. Public baths were part of urban culture in all provinces, although from the end of the IV, community baths began to give way to the private baths. Christians were advised to attend the baths for reasons of hygiene and health, and not for pleasure, although they were also advised not to attend the public games, which were part of the festivals. religious that they considered "pagan".

Education

Traditional Roman education was moral and practical. Stories focused on great personalities were intended to instill Roman values (mores maiorum) in young people. Parents and family were expected to act as role models, and parents with a profession would pass this knowledge on to their children, who could then become apprentices. Urban elites throughout the empire shared a literary culture imbued with the ideals. Greek educational schools (paideia). Many Greek cities financed higher schools, and in addition to literacy and arithmetic, the curriculum also included music and sports. Athens, home to the largest schools of rhetoric and philosophy renowned throughout the empire, it was the fate of many young Romans. As a rule, all daughters of members of equestrian and senatorial orders received instruction. The level of qualification varied, from educated aristocrats to women trained to be calligraphers or scribes. Augustinian poetry praises the ideal of the educated, educated, independent, and art-versed woman, and a woman with high qualifications represented an asset to any family with social ambitions.

Teaching

Formal education was accessible only to families who could afford it. More privileged children could take classes at home with a private tutor. Younger children were taught by a pedagogue, usually a Greek slave or former slave. The pedagogue was responsible for the children's safety, taught them self-discipline and public behavior, and taught them reading, writing, and arithmetic. The remaining children attended a private school run by a teacher (ludi magister), financed through monthly payments from individual parents. The number of schools gradually increased during the empire, creating more and better educational opportunities. Classes could be held regularly in their own rented space or in any available public space, even abroad. Primary education was given to children between the ages of 7 and 12 and classes were not separated by age or gender.

At the age of 14, men from the wealthier classes performed the ritual of passage into manhood. From that age, they begin to receive training to reach a possible position of political, religious or military leadership, training that is usually given by an older member or friend of the family. Secondary education was taught by grammarians (grammatici) or rectors (rhetoric). Grammarians taught mainly Greek and Latin literature, supplemented by lessons in history, geography, philosophy, and mathematics. After the reign of Augustus, Latin authors also became part of the curriculum. The rector was a professor of public speaking and rhetoric. The art of “speaking well” (ars dicendi) was highly valued as an indicator of social and intellectual superiority, and eloquence (eloquentia) was considered the aggregating element of any society civilized. Higher education provided opportunities for career advancement, especially for members of the equestrian order. Eloquence and culture were considered essential characteristics of learned men and worthy of reward.

Literature

In Latin, illiterate (illiteratus) could mean either a person who could not read or write or one without cultural knowledge or sophistication. Estimates point to an average literacy rate in the empire of between 5 and 30% or more, depending on the definition of literacy. The Roman obsession with documents and public inscriptions is an indicator of the value that writing had in society. The Roman bureaucracy it depended on the ability to read and write and both laws and notices were posted in public places. The government made available to illiterate Roman scribes (scribe) capable of reading or writing official documents. The military administration produced a notable amount of written records and reports, and literacy among the military it was quite high. Any form of trade also required a modicum of knowledge of mathematical calculation. There were also a notable number of educated slaves, some quite literate.

Between the centuries I and III there was a significant increase in literary audiences, and while they remained a minority among the population, they were no longer restricted to a sophisticated elite. This led to the rise of consumer literature, oriented to the entertainment of the masses and reflecting the social mobility existing in the imperial period. Illustrated books, including erotic ones, were very popular. Literary works were often read in dinners or between reading groups. However, literacy declined sharply since the crisis of the 3rd century. During the 5th centuries and VI, the ability to read became increasingly rare, even among those in the Church hierarchy.

Recreation and shows

During the government of Augustus, public spectacles were held 77 days a year, a figure that in the reign of Marcus Aurelius was 135. One of the main events of the Roman religious festivals was the performance of games (ludi, origin of the term "ludic"), especially horse and chariot racing. In the plural, ludi almost always refers to games with spectators big scale. The singular Latin ludus ("game, sport, training") had a wide range of meanings, from word games, theatrical performances, board games, elementary school, and even gladiator training schools, such as the Ludus Magnus, the largest of these camps in Rome.

Sand games

Circus games (ludi circensis) were held in structures inspired by Greek hippodromes. Circuses were the largest regularly built structure in the Roman world. The games were preceded by an elaborate parade, the circus pageantry. Competitive events were also held in smaller venues. such as amphitheaters and stadiums. Among the sports modalities, inspired by the Greek models, were the stadium (race), boxing, wrestling and pankration. There were several modalities that were carried out in their own pools, such as naumaquia and a modality of ballet Theatrical events (ludi scaenici) took place on the steps of temples, in large stone theaters or in small theaters called odeons. Although the games originated as religious celebrations Over time, its religious significance ended up being lost in favor of its recreational value. The patronage of the events and shows in the arenas was in charge of the local elites. Despite the high economic costs, his organization was a source of prestige and social status.

The Circus Maximus was the largest arena in all of Rome, with an audience of around 150,000 spectators. Opened in AD 80, the Colosseum became a regular venue for violent sports in the city, with more than 50,000 seats and more than 10,000 feet. The physical layout of the amphitheater represented the hierarchy of Roman society: the emperor presided over its opulent pulpit; senators and high-ranking military officers had the best reserved seats; the women sat shielded from the action; the slaves sat in the worst places and the rest sat where there was a place between the two groups. The crowd could demand a result by whistling or clapping, although it was the emperor who had the last word. The spectacles could quickly become sites of political and social protest, so the emperors often used force to subdue the population. One of the most notable cases was the Nika Riots of 532, which ended with the intervention of Justinian I's army and the massacre of thousands of citizens.

The competition was dangerous, but the drivers were among the most famous and prize-winning athletes of antiquity. One of the stars of the sport was Gaius Apuleius Diocles of Lusitania (present-day Portugal), who drove chariots for 24 years and racked up winnings of 35 million sesterces. Horses were also quite popular, celebrated in art and remembered in inscriptions, often by name. The design of Roman circuses evolved to ensure that neither team had any advantage and to to minimize the number of collisions, although these remained frequent, much to the delight of the crowd. The races were shrouded in an aura of mystery due to their association with chthonic rituals: circus imagery was considered protective or of good luck, and the drivers were often suspected of witchcraft. Chariot racing continued into the Byzantine period, still under imperial patronage, though that of Clive of cities in the VI and V precipitated its demise.

Gladiator Fighting

Competitions between gladiators had their origins in ancient funeral and sacrificial games, in which prisoners of war were selected and forced to fight each other to atone for the deaths of Roman nobles. Some of the earliest gladiatorial fighting styles had ethnic names such as thraex, to give an example. Stage fights were considered to be a munus (services, offers, improvements) and were initially distinct from festival games. During his forty-year reign, Augustus financed eight gladiator shows, in which a total of ten thousand men fought, and 26 hunting shows, which resulted in the death of 3,500 animals. To mark the opening of the Colosseum, Emperor Titus offered 100 days of events in the arena, during which 3,000 gladiators competed in a single day. The Roman fascination with gladiators can be seen in the way they are often depicted on mosaics, murals, and utensils such as lamps.

Roman gladiators were trained fighters and could be slaves, convicts, or simply volunteers. In this type of combat it was not necessary, or even desirable, for the opponent to die. Gladiators were extremely skilled fighters whose training represented an expensive investment of time and money. On the other hand, the noxii were condemned to fight in the arena with little or no training, often unarmed. and without any expectation of survival. Physical suffering and humiliation were considered compensatory justice for crimes committed. These executions were sometimes staged as mythological re-enactments and amphitheaters equipped with stage aids to create special effects. Tertullian considered deaths in the arena no more than a covert form of human sacrifice.

Contemporary historians conclude that the Romans' delight in the "theater of life and death" is one of the most difficult perspectives to explain and understand in this civilization. Pliny the Younger argued that the spectacles of gladiators were beneficial to the people and a way of inspiring them to despise death by manifesting their love of glory and desire for victory, even in the body of slaves and criminals. Some Romans such as Seneca criticized these brutal spectacles, although they saw virtue in the courage and dignity of the defeated fighter, and not in the victorious one, an attitude that finds its maximum expression in the Christians martyred in the arena. However, the literature on the martyrs itself offers detailed and lavish descriptions of bodily suffering, becoming a popular genre sometimes indistinguishable from fiction.

Sports and games

The activities most practiced among children and young people included hooping and ratcheting. Children's sarcophagi often depicted them playing. The girls played with dolls, usually 15–16 cm long and made of wood, terracotta, bone, or ivory. Among ball games, trigon was a favorite, requiring dexterity, along with harpastum, a more violent sport. Reference to pets was common in monuments and children's literature, including birds, cats, goats, sheep, rabbits, and geese. After adolescence, much of the physical exercise of men was of a military nature. The Field of Mars was originally a training ground where young men could hone their warfare and cavalry techniques. Hunting was also considered a proper pastime. According to Plutarch, conservative Romans disapproved of Greek-style athletics that promoted perfection of the body for free, condemning Nero's promotion of Greek-style gymnastics. Some women trained in gymnastics and dance. The famous mosaic "girls in bikinis" shows young women in poses that can be compared to rhythmic gymnastics.

Board games between two opponents were played by people of all ages. Among the most popular were ludus latrunculorum, a game of strategy in which opponents coordinated moves and captured multiple pieces, and ludus duodecim scriptorum (twelve-point), played with dice to arrange the pieces into a grid of letters or words. A dice game that may have been similar to backgammon was also common.

Food

Most apartments in Rome lacked kitchens, although stoves were frequently used. Taverns, bars, inns, and thermopolies sold prepared meals, although eating there or taking food home was common only among the classes lower classes. The wealthier classes preferred reserved meals in their own residence, usually staffed by a cook and kitchen helpers, or at banquets organized in private clubs.

Most of the population obtained 70% of their daily calorie intake by eating cereals and vegetables. One of the main Roman preparations was puls, a porridge made from sliced vegetables., pieces of meat, cheese or aromatic herbs, with which they could make dishes similar to polenta or risotto. The urban population and the army preferred to consume converted cereals into bread. Typically, grinding and baking were done in the same shop. During the reign of Aurelian, the state began to distribute to the citizens of Rome the annona, a daily ration of bread, oil, wine and pork.

Changing Rooms

In a society as conscious of social status as that of Rome, clothing and personal accessories offered an immediate indication of a person's etiquette. Dressing properly was considered to reflect an orderly society. The toga was the characteristic national dress of the Roman man, although it was heavy and impractical, and was used mainly to address political matters, religious rituals and presence at courts. Contrary to popular notion, the casual dress of the Romans could be dark or colorful, and the most common outfit among men during everyday life would be a tunic, cape, and trousers in some regions. It is difficult to study the way Romans dressed in everyday life due to a lack of direct evidence, since the portraiture usually presents the character in symbolic clothing, and surviving fabrics from this period are rare.

The basic garment for all Romans, regardless of gender or social status, was a simple tunic with sleeves. The length differed according to the user: the masculine ones reached half the height between the knee and the ankle, although those of the soldiers were shorter; the women had their robes ankle-length and the girls knee-length. The robes for the poor and slaves were made of carded wool and the length was determined by the type of work performed. The best tunics were made of processed wool or linen. A man belonging to a senatorial or equestrian order wore a purple tunic with two ribbons (clavi), and the greater the dimension, the higher the status of the wearer.

The imperial robe was made of white wool and, due to its weight, it was not possible to dress it properly without assistance. In his work on oratory, Quintilian describes in detail how a public speaker should orchestrate his gestures in relation to his robe. In the technique, the toga is shown with the longest point hanging between the feet, a curved fold at the front, and a protruding flap in the middle. Over the centuries, drapery became more intricate and structured, and by the end of the empire, the cloth formed a tight fold around the chest. The toga praetexta, with a violet fringe representing inviolability, was worn by boys up to the age of ten. and by the executive magistrates and by the priests of the State. Only the emperor was allowed to wear an all-purple toga (picga toga).

In the 2nd century century, emperors and men of status were often depicted wearing the pallium, a cape originally folded around the body, which was also occasionally depicted on women. Tertullian considered the canopy a suitable garment for Christians, as opposed to the toga, and also for literate people, due to its association with philosophers. In the mid-century IV, the toga was practically replaced by the pallium as a symbolic garment of social union.

The fashion and style of Roman clothing changed over time. During the Dominate, the clothing of soldiers and administrative bureaucrats became increasingly decorated, with embroidered stripes of cloth and applied circular emblems to robes. These decorative elements generally consisted of geometric patterns, stylized plant motifs, and in some cases animal or human figures. The use of silk became increasingly common, and silk robes were common among courtiers in the late Empire. The militarization of Roman society and the decline of urban cultural life were reflected in dress habits; in addition to the abandonment of the toga, the use of military-style belts ended up becoming common among civil servants.

Sexuality

The idea of rampant sexual debauchery in the Roman Empire is essentially a later Christian interpretation. In reality, sex in the Greco-Roman world was governed by sobriety and the art of managing sexual pleasure. Sexuality was one of the themes of the mos maiorum, the set of social norms that guided public, private and military life, and sexual conduct was moderated by notions of modesty and shame. Roman censors, magistrates which determined one's social class, had the power to strip citizenship of men of the equestrian or senatorial order who engaged in sexual misconduct. Moral legislation introduced during the reign of Augustus attempted to regulate women's conduct as a way to promote family values. Adultery, which during the republic had been a private matter, was criminalized and defined as an illicit sexual act (stuprum) that occurs between a married man and a married woman.

Roman society was patriarchal. Masculinity was associated with the ideal of virtue (virtus) and self-discipline, while the female correspondent was modesty (puductia). Roman religion promoted sexuality as a sign of prosperity, with religious or common practices to strengthen the erotic life or reproductive health. Prostitution was legal, public, and quite common in the cities. Pornographic paintings or mosaics were prominent pieces in art collections, even in the most affluent and respectable houses. Homosexuality was not reprehensible and it was considered natural for men to be attracted to adolescents of both sexes, as long as they belonged to a lower social status. However, hypersexuality was objectionable in both men and women.

Art

Rome built a society that gave great importance to the arts in its most varied manifestations. In addition to playing a decorative role, the arts also had an educational and socializing role in a context where a large part of the population was illiterate or had little access to the most sophisticated literature. Art enshrined ideologies, narrated historical events, integrated civic festivities and religious rituals, and glorified eminent figures, effectively acting as a lingua franca to which the entire population had access. Roman art initially developed out of the Etruscan tradition. and subsequently absorbed references from Greek culture, making his art largely an extension and variation of it, and making the Romans the primary preservers of the Greek artistic legacy for posterity.

Although the Romans adapted various foreign models, especially from Greece, they were able to develop a tradition that at the end of the republican period and throughout the imperial period acquired innovative and original characteristics, gaining significant independence from the inheritance received and forming their own identity. Even so, in the Empire there were several phases of oscillation between more Hellenistic and imitative tendencies and other more progressive and creative ones. This, added to the many regional variations, the incorporation of Eastern influences, the important changes arising from Christianization and the strong and permanent Roman love for eclecticism, make the art of Imperial Rome a complex mosaic of tendencies, sometimes quite divergent., making it impossible to characterize it as a monolithic aesthetic block. Despite the enormous value placed on works of art, artists had a lower social status, even if they were recognized individuals. The Romans and Greeks viewed artists and craftsmen as manual workers, while at the same time the skill required to produce quality art was recognized, even as a divine offering.

Architecture

Round arches, vaults, and domes are characteristics of Roman architecture that distinguish it from Greek architecture. The introduction of these elements, of an unprecedented dimension in history, was possible thanks to the invention of concrete. This material, known to the Romans as opus caementicium, was made from volcanic ash discovered in the vicinity of Vesuvius, called pozzolans, which was crushed and mixed with calcium oxide. The concrete of the buildings was usually faced with stucco, brick, stone or marble. In some cases, golden sculptures were added to create a dazzling and ostentatious effect of power and prosperity. The constructive quality introduced in Roman architecture significantly increased its durability. Many of the Roman buildings are still intact and in use, most of which are buildings converted to churches during the Christian era. However, in many of the ruins the marble covering has been removed, as is the case in the Basilica of Constantine.

Domes were a common presence in spas, villas, palaces and tombs. The audience rooms of many of the imperial palaces were surmounted by cupolas and were also very common in the garden pavilions. They generally assumed a hemispherical shape and were totally or partially hidden from the outside, being in many cases topped by an oculus and, sometimes covered by a conical or polygonal roof. With the collapse of the Western Empire, vaulted construction declined. However, this style continued in force in the East through Byzantine architecture.

It was during the governments of Trajan (r. 98-117) and Hadrian (r. 117-138) that the empire reached its peak both territorially and artistically, having begun an immense program for the construction of monuments, assemblies, gardens, aqueducts, spas, palaces, pavilions, sarcophagi and temples. The introduction of the arch, the dome and the use of concrete allowed the construction of large vaulted ceilings in public spaces and complexes such as spas or basilicas. Among the most notable examples of domes are Agrippa's Pantheon, the Baths of Diocletian, and the Baths of Caracalla. Dedicated to all the planetary gods, the Pantheon is the best-preserved ancient temple in the world, with its dome still intact. The last major building programs in Rome took place during the reign of Constantine I (r. 306-337), including the Arch of Constantine near the Colosseum in Rome.

Painting

Painting was one of the most popular arts of the Roman Empire, but little is known about it because the vast majority of records have been lost to time. Much of what is known about Roman painting is based on the interior decoration of private residences, particularly the frescoes that have been preserved in Pompeii. Discovered in the 18th century, this city was buried under the eruption of Vesuvius in 79, allowing it to remain relatively intact. From this set of works —which, although rich and varied, is a tiny fraction of what was produced and covers a very limited period— a chronology of styles was established that has been applied to the entire imperial pictorial legacy. According to this proposal, Roman painting evolved from Greek examples of purely geometric wall decoration, progressively incorporating figurative elements into architectural or landscape settings, often using Greek models or citing famous Greek works in creative reinterpretations, even presenting in some examples a great sophistication and sumptuousness. In addition to decorative friezes and panels with geometric and plant motifs, the mural painting represents scenes from mythology, landscapes and gardens, recreation, shows, work and daily life, and even erotic scenes. Birds, animals, and marine life are often rendered with special care regarding artistic detail.