Roman citizenship

In ancient Rome, Roman citizenship offered extensive and fundamental rights. All of these rights form Roman citizenship ( jus civitas or civitas ). Originally, the right of citizenship , that is to say the recognition of citizenship, was reserved to free men registered in the tribes of the city of Rome and its bordering territory. In -89, it was extended to all free men in Italy; three centuries later, in 212, it was granted to all free men in the Roman Empire. The extension of citizenship was a powerful vector of attraction in ancient Rome.

Citizenship in ancient Rome (Latin: civitas ) was a privileged legal and political status granted to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and government.

Roman women had a limited form of citizenship. They were not allowed to vote or stand for civil or public office. The wealthy may participate in public life by financing construction projects or sponsoring religious ceremonies and other events. Women had the right to own property, to start businesses, and to obtain a divorce, but their legal rights varied over time. Marriages were an important form of political alliance during the Republic.

Citizens of the client and allied state (socii) of Rome could receive a limited form of Roman citizenship as the Latin right. These citizens could not vote or be elected in the Roman elections.

Freedmen were former slaves who had gained their freedom. They were not automatically granted citizenship and lacked some privileges, such as running for executive positions. The children of freedmen and freedwomen were born free citizens; for example, the father of the poet Horace was a freedman.

Slaves were considered property and lacked legal personality. Over time, they acquired some protections under Roman law. Some slaves were freed by manumission for services rendered, or by testamentary disposition when their master died. Once free, they faced few barriers, beyond normal social stigma, to participating in Roman society. The principle that a person could become a citizen by law and not by birth was enshrined in Roman mythology; when Romulus defeated the Sabines in battle, he promised the captives of war in Rome that they could become citizens.

Rights and duties of the Roman citizen

Civitas Romana optimo jure ( Roman citizenship with full rights)

Political and military rights

- Jus suffragii : the right to vote

- Jus militiae : the right to join the Roman legion, and to receive pay and a share of the spoils

- Jus honorum : the right to be elected as a magistrate

- Juscenso : the right to property

- Jus sacrorum : the right to participate in the priesthood

- Jus conubii : the right to marry

- the right to bequeath your property to your heirs

The exercise of the vote is carried out according to the electoral division of the tribute comitia, so that each citizen is assigned to a tribe.

Election to the commissariat, the first magistracy of the cursus honorum , required a minimum census of 400,000 sesterces. The jus honorum was thus restricted to the richest. Similarly, only citizens of the wealthier classes were allowed to join the legion, until Marius' reform lifted this restriction in -105.

Political and military duties ("munus" in Latin)

- census : obligation to register, under penalty of loss of citizenship. The census is accompanied by linking the citizen to an urban or rural tribe. The citizen's wealth is also evaluated, determines his rank in society and his class and his century of membership for military incorporation operations and for the voting process (comices centuriates);

- jus militae : obligation to serve in the Roman legion, right to receive a salary. Under the Republic, before the Marian reform, only the citizens of the centuries who have a certain threshold of wealth are incorporated, leaving the poorest (proletarians) exempt;

- tributum – occasional contribution to military expenses proportional to declared wealth, abolished in 167 BC. AD;

- inheritance tax, established by Augustus to pay discharge premiums for soldiers.

Civil rights

The Roman citizen also has civil rights:

- jus conubii (or conubium ): legal right to marry a Roman woman.

- jus commercii (or commercium ): right to buy and sell in Roman territory.

- jus legis actionis : right to take legal action before a Roman court.

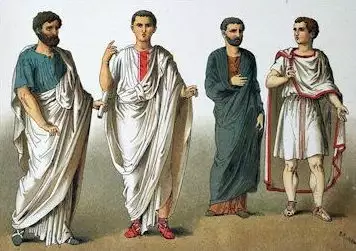

- right to wear the toga and the tria nomina (name, surname and nickname), distinctive signs of the citizen.

- right to make a will.

- jus commercium : capacity to enter into commercial transactions.

Laws were passed to suppress the usurpation of Roman citizenship (in -95, lex Licinia Mucia , against fraudulently registered Italians)

Faced with Roman justice, the citizen benefits from protections:

- Jus auxilii : right to the assistance of a tribune of the plebs for his defense

- Jus provocationis : right to appeal to the people when a judicial decision is considered bad, according to the lex Valeria of -300. However, this right is not exercised in the army, because the consul's imperium gives him the right of life or death over citizen-soldiers.

- Corporal punishment and the death penalty inflicted by lictors only by whipping with rods and beheading with an axe, except any other infamous punishment. Other penalties are provided for very specific cases (parricide, loss of chastity of a vestal).

Rods were prohibited for a citizen by the lex Portia of Cato the Elder, and it was admitted that capital punishment could be avoided by voluntary exile.

Onomastics of the Roman citizen

Roman citizenship is manifested in the name of those who are beneficiaries of it. The full nomenclature of a citizen includes his praenomen , his nomen or gentile (surname), his descent, manifesting hereditary transmission of citizenship, and his tribe. From the end of the republic, the cognomen , nickname, is added to this nomenclature. Praenomen , gentile, and cognomen form the tria nomina that allows immediate identification of a citizen, especially in Latin inscriptions. Later, with the diffusion of citizenship, the exhibition of tria nominait becomes less rigorous from the end of the second century of our era: the inscriptions mention the tribe less and less and the texts present more and more often only two names instead of the three classical names. The general grant of citizenship by Caracalla in 212 completed to precipitate this evolution.

Roman women's rights

Women, as in many civilizations, are politically minor and are excluded from most rights. However, it is an abuse of language and an anachronism to say that free Roman women are not citizens, even if they never wear the Tria Nomina , do not participate in the comitia or exercise the slightest magistracy, which from a contemporary point of view is not makes them members of the civic body: in fact, there are inscriptions that evoke the granting of the right of citizenship by the emperor to former soldiers at the same time as to their wives, so that they can unite within the framework of a legitimate marriage or conubio ; sometimes even citizenship is granted explicitly and by name to a woman ("to Julianus and his wife Ziddina" in the Banasa Tablet, dated 166).

To be a Roman citizen is, therefore, to be able to be the mother and wife of male citizens, the only ones who really enjoy political rights but who have few prerogatives for themselves (in terms of inheritance, however, they do exist). However, their status allows them to be elected as Vestals, to participate in certain traditional cults, and to enter into legal marriage.

Some aspects of the Roman tradition grant rights to women that they do not have in other cultures:

- their testimony is admissible in court (except that of courtesans, who are venal by definition);

- they can inherit in their own right;

- they are entitled like men to the eulogy at his funeral, a tradition that Titus Livy traces back to the time of the sack of Rome by the Gauls in -390, when the Roman ladies had offered their jewels to finance the ransom demanded by the Gauls.

Finally, according to a tradition that the Romans trace back to the abduction of the Sabines, Roman women were exempt from all domestic or agricultural work except spinning wool and raising children.

Civitas Romana sine suffragio (Roman citizenship without suffrage)

The Roman civitas sine suffragio is a true legal citizenship, but politically incomplete:

- Citizens sine suffragio have Roman private law ( commercium , conubium , legal action).

- Judicial rights are real: the provocatio ad populum (appeal to the people) that protects against the coercitio (right of coercion) of the magistrates is recognized for all citizens. The tribune of the plebs convenes a tribute committee or concilium plebis to defend sine suffrage citizens who consider themselves wronged.

- But sine suffrage citizens have no political rights. They are included in Rome in separate lists, but not in the tribes (because they do not vote and are not eligible); they do not belong to the plebs and do not participate in their assemblies (comices tributes and concilium plebis ), nor in the centuriate committees of the populus. In all, the Roman civitas sine suffragio has more charges ( increased tributum and dilectus which is done outside the legions) than honors (that of being cives Romanus ). It was a penalty.

- From 350 to 268, Rome imposed it on a certain number of the vanquished, thus stripping them of sovereignty (but not of local autonomy) that allowed them to expand their territory and their population (for war).

- But civic logic wanted full citizenship, and sine suffragio citizens gradually fell in line with the others by receiving optimo jus (a procedure completed in 188).

- But this extended the ager Romanus and transformed the city into a territorial state, ultimately ungovernable within the framework of the city's institutions (because the magistrates can no longer be effectively controlled); also, from 268 to 90, Rome preferred the more flexible framework of the federation (unequal treaties with the allies), which allowed juxtaposing the Roman ciuitas and its imperium (zone of influence).

The legal statutes of the ingenii (nés libre) dans l'empire de Rome

For the Romans, jus gentium (natural law, international law) is different from jus ciuile (law of a city). For example, the right to own land or found a family is ius gentium ; by contrast, the right to legally sue or marry falls under the ius ciuile .

Roman citizens

In public law, the Roman citizen had the right to vote (unless he belonged to a city-state that had received the civitas sine suffragio , but this status disappeared in 188 BC), and, if he meets the conditions of censorship, the right to vote. eligibility for the judiciary. Under the principality, this no longer matters (elections disappeared in Rome, under the control of the aristocrats in the Roman municipalities). In private law, the Roman citizen has the right to use the jus ciuile in three domains (the conubium , the right to contract the Roman marriage, only legal; the commercium, right to acquire and dispose of assets, including the right to ester; legal actions, to assert their rights in court). Private law, which is the same for all citizens, is set from the laws of the "XII Tables" (450 BC). But as of 150 AD, honoriores and humiliores are distinguished, who are not treated in the same way in criminal law (torture allowed for the latter).

Latinos

Ancient latin

The Latini ueteres (ancient Latins, originally those of Lazio and the Latin colonies founded before 338), whose status is no longer granted after 268 (those who had it before keep it), have civil rights and in their hometown, but in addition, they have the juicy romans (private law) (conubium, commercium, legal action), the right to vote when they are present in Rome, but not the right to be elected), and the right to emigrate (they can move and become Roman citizens). ).

Latin colonialii

The latini colonialii (Latins of the 12 Latin colonies founded after 268, until about 180), whose status seems slightly less advantageous, could become Roman citizens by settling in Rome; after 206 (or 187) this was only possible if they left a male child in their Latin city of origo.

Pilgrims

The Latin pilgrims (foreigners with Roman citizenship) belong to a city of pilgrims having received Latin law (essentially private law). These Latins could become Roman citizens after having held a magistracy in their city (minus Latium created around 125 BC) or by becoming a decurion ( maius latium , created in the time of Emperor Hadrian). Depending on the case, the cities could receive the “small” or the “great” Latin law. The extension of Latin law ( minus Latium or maius Latium depending on the case and the time) was very important: it was given to cities of pilgrims or to entire regions (eg: Cisalpine Gaul in 88 BC, Iberia under Vespasian, in April 75 J.-C.) without there being colony foundation. There is no "Latin citizenship", but under the Empire, citizens of Latin municipalities (pilgrim cities that have received Latin law and modified their institutions to align with the Roman model) are called not "pilgrims", but "Latins". ". the citizens". They are citizens of their municipium d'origo , where they follow local private law and have political rights. But since the city received Latin law, all citizens benefit from Roman private law, and the elites have Roman citizenship.

Vagabonds

Ordinary tramps

Ordinary wanderers are attached to a city or a community (people). They use their local, private and public law among themselves. They have no Roman political rights, nor the conubium . On the other hand, the ius gentium that is recognized, allows from 242 av. AD to settle disputes over property (ownership, trade) with the Romans. Pilgrims could obtain Roman citizenship individually or collectively, depending on the policy of the Senate, the great generals of the first century BC. C. and then the emperors.

Pilgrims "fingers"

The "deditas" pilgrims belong to a city or a community that has not seen its collective status recognized by Rome: eg. the native Egyptians during Octavian's conquest in 30 BC. , the Jews of Jerusalem after the revolt of 66-70 CE. The little fingers use only the jus gentium (limited in family matters, because no potestasof the father over the children, nor of a legally recognized will). A peregrine deditice can only become a Roman citizen by first being admitted as a citizen of a pilgrim city (for example, an Egyptian would first have to become a citizen of Alexandria before being able to become a Roman citizen). The deditice pilgrims were the only free men excluded from general adherence to Roman citizenship in AD 212 (Antoninian Constitution or Edict of Caracalla); as the Egyptian nomes had been municipalized (regarded as cities) by Septimius Severus, the Egyptians were also affected by the measure.

The statutes of the liberti (freedmen)

Freed Roman citizens

In public law, the freedman only has the right to vote (he is not eligible because he does not have the jus honorum ), and he exercises it most often in one of the four urban tribes. In private law, the freedman has the conubium , the commercium , and the right to sue; his children are considered naïve , thus Roman citizens in their own right. The freedman owes by law to his former master (or heir) who became his boss:

- respect (no legal action without the authorization of a magistrate)

- charges set by the postage contract (professional assistance to the captain)

- his estate If the freedman has no legally recognized heir

Junian Latin Freedmen

His status was fixed under Augustus by the Junian law (17 BC). This less advantageous status can be explained by the fact that certain freedmen molested the nobles. Junian Latin freedmen are slaves who were freed informally (by letter, in front of friends, not in front of a magistrate) or who were freed when they were under 30 years old. They live free and have private rights equivalent to Latin law (commercium, conubium) in case of marriage with a Roman spouse, the children are Roman citizens (under Hadrian). On their death, they cannot make a will and their property reverts to their patron, who may sell his right of patronage to another Roman citizen.

The Junian Latin can become a Roman citizen by official postage from his patron, rendering services to the community (6 years of service in the vigil cohorts, construction of ships for 6 years for the anona of Rome, construction of buildings of 100,000 sesterces after the fire of 1964, making bread for 3 years on behalf of the state), by imperial concession (with the patron's agreement). The Latin Junian who was freed because he had been freed before 30 years became a Roman citizen when he had a one-year-old son (in AD 75, true for all Junians). These Junian Latin freedmen should not be confused with pilgrim citizens of Latin right; the only point in common between them (which justifies the name "Latin") is that they have Latin law (Roman private law).

The wandering freedmen

If the master is a pilgrim, the freedman obtains his master's local citizenship and cannot change it without the consent of his former master who has become his boss.

Freedmen

They are so because their master was a Dedita pilgrim, or because they were judged unworthy to become Roman citizens like their master (for a profession considered infamous, or for a serious offense during their time of slavery of a 4 AD law). They only have the ius gentium and are prohibited from staying in Rome and within a radius of 100 Roman miles (150 km). When they die, their property reverts to their patron.

Freedmen of freedmen

Slaves of slaves who are freed follow the legal status of their freed master's patron.

Latino citizenship

From its beginnings, Rome practiced a policy of close alliance with the cities of Lazio within the Latin League. After various tensions, including the revolt of the Latins in -340, Rome had to grant Roman citizenship in -338 to the free inhabitants of the cities of Latium. However, as the exercise of the vote could only be done personally and in Rome itself, this citizenship was granted without the right to vote (citizenship sine suffragio also known as "Latin citizenship"), and therefore without access to the Roman magistracies. . The Latin citizen can only vote in the tribute comitia if he is present in Rome on the day of the election. He is then registered in one of the 35 drawn tribes.

Latin citizens have civil rights and the protection of Roman laws, can acquire or sell property ( jus commercii ), but are deprived of political rights except in Latin city-states (Latin municipium). A Latin citizen can legitimately marry a Roman woman, but her children will be Latin citizens, unless the husband possesses jus conubii in a personal capacity. Otherwise, your children automatically have Latino citizenship.

The Latin citizen could, however, thanks to the juice of migration , establish himself in Rome, join a tribe and thus have full exercise of citizenship.

These two levels of citizenship spread to Italy and beyond during the founding of a Roman colony enjoying full citizenship ( civitas cum suffragio ) and a Latin colony with more limited rights ( civitas sine suffragio ).

Acquisition of Roman citizenship

Roman citizenship is acquired by birth if one is the son of a Roman citizen or a Roman freedman.

The freedman acquires an incomplete citizenship, he is marked by the servile stain: after Augustus he cannot claim municipal honors. A freedman registers with one of the urban tribes to prevent an ambitious man from accumulating a mass of new voters in his own tribe. Furthermore, enrolling him in an urban tribe means that most of the poor, of which the freedman is a part, are found in all four urban tribes. The poor thus have less weight in the votes of the tributary comitia because the votes are counted by tribes and not by heads.

Citizenship can be acquired by naturalization of a free man, then we speak of granting viritan ( viritim ), that is, on a personal basis. In the latter case, the new citizen takes the surname of the magistrate who made him a citizen and registers with his tribe. The naturalization of a free man is often explained by patronage ties (see client). After Augustus, only the emperor can thus grant individual citizenship. This decision is often made following a recommendation made by a boss. The new citizen takes the surname (gentilice) of the emperor: Iulius or Claudius under the Julio-Claudians, Flavius under the Flavians, Ulpius ,or Aurelius under the Antonines, Septimius or Aurelius under the Severans. The Tabula Banasitana testifies to this procedure for the time of Marcus Aurelius. It shows that the granting of citizenship was still tightly controlled by the emperors.

However, citizenship is being granted more and more widely, especially under the Empire, without criteria of origin, birth, or religion, individually or to all free men of a long-pacified territory. Rome is much more welcoming than the Greek cities. For example, despite important cultural differences, there are Roman Jewish citizens, such as Flavius Josephus or Cn. Pompeius Paullus (Paul of Tarsus). In the Acts of the Apostles, Paul declares his Roman citizenship after being defeated without trial (cf. Acts 16:37), which frightens the strategists of the city of Philippi.

At the end of the Republic and under the Empire, military service in the auxiliary troops was for many provincials the means of acquiring Roman citizenship at the end of their service. Citizenship is first conferred exceptionally as a reward for outstanding merit, as evidenced by the Asculum Tablet: in -90 Cn. Pompey Strabo, Pompey's father, granted Roman citizenship to Iberian horsemen who had served during the Social War. Only from Claude onwards is citizenship systematically conferred on auxiliary soldiers who have completed 25 years or more of service and who have received an honorable discharge. Military diplomas attest to this procedure and its evolutions: soldiers also received the conubiumfor their wives and, until 140, citizenship for their already born children.

Citizenship is also granted to an entire city for services rendered in the wars waged by Rome. The granting of this citizenship is then often done in stages: first the Latin law, then the Roman citizenship for all the inhabitants afterwards. Within the framework of Latin law granted to a city, the magistrates of the city, upon leaving office, become Roman citizens. The other members of the city are granted the conubium and the commercium . Since Hadrian, the older Latin law conferred citizenship on all decurions of the city. Latin law, developed at the end of the republic from past relations between Rome and the allies ( socii) Italians, was, under the empire, a powerful means of integration and romanization of the local elites and civic aristocracies of the empire, but essentially in the western part of the empire. Latin law can be conferred on a city whose law is foreign to Roman law (pilgrim city) but, in general, it is accompanied by a change of status: the city can become a Latin colony —many examples are known in Gaul— or it can become a Latin municipality: in both cases the city receives a new constitution more in line with Roman law but which provides an important margin of adaptation and local autonomy. Under the republic and at the beginning of the empire, an already existing city that collectively receives Roman citizenship for its inhabitants becomes a Roman municipality, this was still the case with Volubilis at the start of Claudius' reign. Subsequently, the creation of a municipality conferred only Latin right. A Latin colony or a Latin municipality can then become a Roman colony: citizenship is conferred on all free inhabitants of the city. However, not all cities were familiar with this evolution of the rights of their citizens. Some examples are well known, such as the case of Lepcis Magna, a free city in proconsular Africa that became a Latin municipality under Vespasian and a Roman colony under Trajan. However, not all cities were familiar with this evolution of the rights of their citizens. Some examples are well known, such as the case of Lepcis Magna, a free city in proconsular Africa that became a Latin municipality under Vespasian and a Roman colony under Trajan. However, not all cities were familiar with this evolution of the rights of their citizens. Some examples are well known, such as the case of Lepcis Magna, a free city in proconsular Africa that became a Latin municipality under Vespasian and a Roman colony under Trajan.

Historical summary

Some important dates mark the evolution of the granting of citizenship:

- The lex Iulia de Civitate Latinis Danda or lex Julia (-90) grants Roman citizenship to the peoples of Italy who had not rebelled after the assassination of Livio Druso.

- The lex Plautia Papiria (-89) extends full citizenship to all free inhabitants of Italy south of the Po. This measure allows closing the Social War satisfying its main demand.

- in -88, the lex Pompeia grants Latin citizenship to all the inhabitants of Cisalpine Gaul.

- in -65, the Lex Papia represses the usurpation of Roman citizenship.

- in -49, the lex Roscia , adopted at the beginning of the civil war, granted Roman citizenship to all the inhabitants of Cisalpine Gaul. All of Cisalpine Gaul was then annexed to Italy in -42.

- in -44, at the initiative of Marc Antoine, Roman citizenship is given to all free men in Sicily, this measure was partially revoked by Augustus.

- in 48 AD C., as evidenced by the Claudian Table of Lyon, Claude granted access to the magistracies and the senate to the notables of Gaule Chevelue: this is often seen as the granting of jus honorum . Claude, without sacrificing a profound respect for citizenship, was, by reason of his censorship in particular, the architect of an important opening of citizenship, an opening sometimes considered too generous by his contemporaries, who, like Seneca, mocked him. an emperor who wished to see all the Gauls dressed in tunics. According to Edmond Frézouls, the Tabula Clesiana also bears witness to this Claudian conception in which citizenship became the instrument of balance for the empire.

- Vespasiano (69-79) grants Latin law to all the cities of Hispania.

- finally in 212, Roman citizenship to all free men of the Empire (Edict of Caracalla).

Rights

- Ius suffragii : The right to vote in Roman assemblies.

- Ius honorum : The right to stand for civil or public office.

- Ius commercii : The right to enter into legal contracts and own property as a Roman citizen.

- Ius gentium : The legal recognition, developed in the 3rd century BC, of the growing international scope of Roman affairs, and the need for Roman law to deal with situations between Roman citizens and foreign persons. The ius gentium was thus a Roman legal codification of the widely accepted international law of the time, drawing on the highly developed commercial law of the Greek city-states and other maritime powers. The rights granted by the ius gentium were considered to be held by all people; therefore, it is a concept of human rights rather than rights attached to citizenship.

- Ius conubii : The right to have a legal marriage with a Roman citizen according to Roman principles, to have the legal rights of the paterfamilias over the family, and to have the children of such a marriage counted as Roman citizens.

- Iusmigrationis : The right to preserve one's level of citizenship when moving to a polis of comparable status . For example, members of the cives Romani (see below) kept their full civitas when they migrated to a Roman colony with full rights under law: a colonia civium Romanorum . Latins also had this right and kept their ius latii if they moved to a different Latin state or to a Latin colony ( Latina colonia ). This right did not preserve one's citizenship status if one moved to a lower -class neighborhood. legal status; Full-fledged Roman citizens moving to a Latin colonies were reduced to the level of the ius Latii , and such migration and reduction in status had to be a voluntary act.

- The right to immunity from some taxes and other legal obligations, especially local rules and regulations.

- The right to sue in court and the right to be sued.

- The right to have a legal trial (to appear before a proper court and defend oneself).

- The right to appeal the decisions of the magistrates and to appeal the decisions of the lower courts.

- According to the Porcian Laws of the early 2nd century BC. C., a Roman citizen could not be tortured or flogged and could commute death sentences to voluntary exile, unless he was found guilty of treason.

- If accused of treason, a Roman citizen had the right to stand trial in Rome, and even if sentenced to death, no Roman citizen could be sentenced to die on the cross.

Roman citizenship was required to enlist in the Roman legions, but this was sometimes ignored. Citizen soldiers could be beaten by centurions and senior officers for disciplinary reasons. Non-citizens joined Auxilia and gained citizenship through the service.

Citizenship classes

Legal classes varied over time, however the following classes of legal status existed at various times within the Roman state:

Cives romani

The cives romani were full-fledged Roman citizens, enjoying full legal protection under Roman law. Cives Romani were subdivided into two classes:

- The non optimo iure held by the ius commercii and the ius conubii (property and marriage rights)

- The optimo iure , which held these rights as well as the ius suffragii and the ius honorum (the additional rights to vote and exercise office).

Latin

The Latini were a class of citizens who held the Latin Law ( ius Latii ), or the rights of ius commercii and iusmigrationis , but not the ius conubii . The term Latini originally referred to the Latins, citizens of the Latin League who came under Roman control at the end of the Latin War, but eventually became a legal description rather than a national or ethnic one. Freed slaves, those of the cives romani convicted of crimes, or citizens settling in Latin colonies could receive this status under the law.

Society

The socii or foederati were citizens of states that had treaty obligations with Rome, under which certain legal rights of state citizens under Roman law were generally exchanged for agreed levels of military service, i.e. Roman magistrates had the right to recruit soldiers for the Roman legions. of those states. However, foederati states that had at some point been conquered by Rome were exempt from paying tribute to Rome due to their treaty status.

Growing dissatisfaction with the rights given to the socii and with the growing demands for manpower from the legions (due to the protracted Jugurthine War and the Cimbrian War) ultimately led to the Social War of 91–87 BC. C. in which the Italian allies rebelled against Rome. .

The Lex Julia (in its entirety the Lex Iulia de Civitate Latinis Danda ), approved in 90 BC. C., granted the rights of cives Romani to all the Latin states and socii that had not participated in the Social War, or that were ready to cease hostilities immediately. . This was extended to all Italian socii states when the war ended (except for Gallia Cisalpina), effectively removing socii and Latini as legal and citizenship definitions.

Provincial

Provincials were those people who fell under Roman influence or control, but lacked even the rights of the Foederati , having essentially only the rights of the ius gentium .

Pilgrim

A peregrinus (plural peregrini ) was originally anyone who was not a full Roman citizen, that is, someone who was not a member of the cives Romani . With the expansion of Roman law to include more gradations of legal status, this term became less widely used, but the term peregrini included those of Latini , socii , and provincials , as well as the subjects of foreign states.

Citizenship as a tool of romanization

Roman citizenship was also used as a tool of foreign policy and control. Colonies and political allies would be granted a "lesser" form of Roman citizenship, with various graduated levels of citizenship and legal rights existing (the Latin right being one of them). The promise of improved status within the Roman "sphere of influence" and rivalry with neighbors for status kept the focus of many of Rome's neighbors and allies focused on the status quo of Roman culture, rather than trying to to subvert or overthrow Rome. influence.

The granting of citizenship to allies and conquered was a vital step in the Romanization process. This step was one of the most effective political tools and (at the time in history) original political ideas.

Previously, Alexander the Great had tried to "mix" his Greeks with the Persians, Egyptians, Syrians, etc. to assimilate the people of the conquered Persian Empire, but after his death this policy was largely ignored by his successors.

The idea was not to assimilate, but rather to convert a defeated and potentially rebellious enemy (or their children) into Roman citizens. Instead of having to wait for the inevitable revolt of a conquered people (tribe or city-state) like Sparta and the conquered helots, Rome tried to make those under her rule feel like they had a stake in the system.

The Edict of Caracalla

The Edict of Caracalla (officially the Constitutio Antoniniana in Latin: "Constitution [or Edict] of Antonine") was an edict issued in the year 212 AD. Roman citizenship and all free women of the Empire received the same rights as Roman women, with the exception of dediticii , people who had become subjects of Rome through surrender in war and freed slaves. Before 212, for the most part only the inhabitants of Italy had full Roman citizenship. Colonies of Romans established in other provinces, Romans (or their descendants) living in provinces, inhabitants of various cities in the Empire, and some local nobles (such as kings of client countries) also had full citizenship. Provincials, on the other hand, were generally non-citizens, although some had the Latin right.

The Book of Acts of the Bible indicates that the Apostle Paul was a Roman citizen by birth, although it does not clearly specify what kind of citizenship, a fact that had considerable influence on Paul's career and on the religion of Christianity.

However, in the century before Caracalla, Roman citizenship had already lost much of its exclusivity and was more widely available.

Romanitas, Roman nationalism and its extinction

With the settling of Romanization and the passing of generations, a new unifying feeling began to emerge within the Roman territory, the Romanitas or Roman way of life , the once tribal feeling that had divided Europe began to disappear (although never quite). ) and to mix with the new wedge patriotism imported from Rome with which to be able to ascend at all levels.

The romanitas , romanidad or romanismo would last until the last years of unity of the pars occidentalis, a moment in which the old tribalisms and proto-feudalism of Celtic origin, latent until then, would resurface, mixing with the new ethnic groups of Germanic origin. This can be seen in the writings of Gregory of Tours, who does not use the Gallo-Roman-Frank dichotomy, but instead uses the name of each of the existing gens of the time in Gaul (Arverni, Turoni, Lemovici, Turnacenses, Bituriges , franci, etc.), considering himself an Arverni and not a Gallo-Roman; being the relations between natives and Franks seen not as Romans against barbarians, as is popularly believed, but as in the case of Gregory, a relationship of coexistence between Arverni and Franks (Franci) as equals.

We must also remember that Clovis, King of the Franks, was born in Gaul, so according to the Edict of Caracalla that made him a Roman citizen by birth, in addition to being recognized by Emperor Anastasius I Dicorus as consul of Gaul, thus his position of power was reinforced, in addition to being considered by his Gallo-Roman subjects as the legitimate viceroy of Rome; understanding that Romanitas did not disappear so abruptly, he noted its effects centuries later with Charlemagne and the Translatio imperii .

In ancient Rome, Roman citizenship offered broad and fundamental rights. All of these rights form Roman citizenship ( jus civitas or civitas ). Originally, the right of citizenship , that is to say the recognition of citizenship, was reserved to free men registered in the tribes of the city of Rome and its bordering territory. In -89, it was extended to all free men in Italy; three centuries later, in 212, it was granted to all free men in the Roman Empire. The extension of citizenship was a powerful vector of attraction in ancient Rome.

Contenido relacionado

Gaius (jurist)

Twelve Tables

Senatus consultum