Rodolphe Topffer

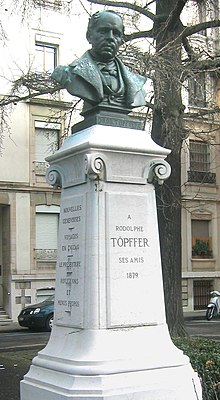

Rodolphe Töpffer (Geneva, January 31, 1799 - June 8, 1846) was a Swiss educator, writer, painter and caricaturist, considered by many to be the father of the modern comic strip. theoretical, his works being more similar to the graphic novel than to the manifestations that would follow.

Biography

The son of an amateur painter of genre paintings and landscapes, who would awaken a taste for William Hogarth's engravings, this was the main inspiration for his comic strips. As a writer, Töpffer is influenced by Molière, Racine, Virgil, Tacit, and above all, by the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He was trained in Paris and wrote mainly in French.

By 1820 he returned to Geneva where, unable to follow the same artistic career as his father, he decided instead to devote himself to literature. He becomes an adjunct teacher of Latin, Greek, and ancient literature at Pastor Heyer's boarding house.

He first worked as a teacher and on November 6, 1823, he married a friend of his sister Ninette, Anne-Françoise Moulinié (1801-1857), from whom he would have four children: Adele-Françoise (1827-1910), the last direct descendant, who arrived in the city of Geneva all the manuscripts of his father; Francois (1830-1870); Jean-Charles (1832-1905) and Françoise-Esther (1839-1909).

A year later, in 1824, he set up a boarding school where he would welcome students from all over Europe.

In 1827, partly to entertain his students, he made a small album entitled Les Amours de M. Vieux-Bois, though he did not publish it for another ten years. In 1829 he did publish Voyages et aventures du Docteur Festus, which received praise from Goethe, and this was followed by Histoire de M. Cryptogramme (1830, published in L& #39;Illustration in 1845), Mr Pencil (1831, published in 1840), Histoire de M. Jabot (1831, put up for sale in 1835), The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck (1837), M. Crépin (1837) and Histoire D'Albert (1844). They are horizontal format albums, aimed at adult readers, with a strip of cartoons per page and one or two lines of text at the bottom of each cartoon, characterized by their spontaneity and loose lines. Töpffer's albums were very successful and were released in France, Germany and the US, generating a multitude of imitations.

As a writer he published My Uncle's Library (1832), Geneva Novels (1829-1840) and some Zigzag Journeys (1844), among other works.

In 1834 he became a Conservative Member of Parliament for the Canton of Geneva.

His Essay on Physiognomy of 1845 is considered the first theoretical text on comics. Töpffer was well aware of the potential of the medium:

“The story in paintings to which the art critique pays no attention, and which seldom disturbs the touches, has failed instead to exert a great attraction. And this to a greater degree than literature itself, since from the fact that there are more people looking at than people reading, it exerts its attractiveness especially about the boys and the masses, that audience that can be perverted and that it would be particularly desirable to help educate. The drawn tale, with that double advantage that comes from its greater concision and its relatively greater clarity, can and must overcome other means of expression as it can be directed with a truly living attitude to a greater number of spirits and since the one who uses it — whatever the context is — will have an advantage over those who choose to express themselves through books.”

The pedagogue

After the time of Pastor Heyer's pension, Töpffer took up the habit of organizing excursions. He also at his own institution would take one or two of his resident students on "school field trips"; every year.

These are much larger school trips, often on foot, with his wife Kity who "traveled for the relief of the injured, and the approval of those who behave themselves. She was wearing a green veil, and a small first-aid kit in her bag & # 34;. On his return, he wrote and illustrated the result of his excursions, first in the form of a manuscript and, from 1832, in the form of an autographed album.

Her travel records will be at least as important as the rest of her literary work. Taken up and restructured by Töpffer, they constitute the content of two new volumes of travel records: the Zigzag Journeys published in Paris in 1844 and the New Zigzag Journeys published in 1854. after his death. Goethe admired his Töpffer texts to the same extent as his & # 34; literature in prints & # 34;.

The writer

Töpffer was influenced by Molière, Racine, Virgil, Tacitus and others, but above all by the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In 1824, his first work was a scholarly edition of ancient Greek texts, Demosthenes' Political Harangues and in 1826 he anonymously published his first art criticism on an exhibition at the Rath Museum in Geneva. In 1841, Töpffer's literary reputation was established by the publication of the New Genevans at the Charpentier publishing house in Paris. The consecration came with the critical study that Saint-Beuve did on Töpffer in the French magazine Revue des Deux Mondes.

His «literature in prints» (which Töpffer called «stories in prints») produced from 1827 until his death numbered seven plus one posthumous and four unpublished. They represent a great success in their time. In 1842, a piece of news appeared about Autography Essays, a technique that he preferred to Lithography to make his comic strip works, and in 1845, he was interested in his Fisionomy Essay (see Physiognomy) at the origin of what he calls "literature in prints", he writes the first theoretical work on comics.

Parallel to his literary creations, Töpffer wrote his first piece The Artist and had Kity and a group of his students perform it on February 12, 1829. He wrote many others that were performed for the edification of his students. Töpffer never accepted that his pieces be published during his lifetime and the same would have been his "stories in prints" without Goethe's insistence.

The political man

Töpffer had very conservative views unlike his father who advocated liberal ideas. In 1834, Rodolphe Töpffer became a conservative member of the Geneva cantonal parliament, a responsibility he left in 1841 after a first triumph of the liberals. Later, in 1842, he became a polemicist in the newspaper Courrier de Genève (Geneva Messenger) « I would like to have ten arms, ten pens, ten newspapers and, above all, ten good eyes, to make a war that I believe is basically honesty against vice since, if it were only a matter of interest here, of what is vulgarly called politics, I would not have, I am sure, ideas of what to write a line» he wrote a de La Rive of September 20, 1842. The Courrier de Genève was suspended on March 22, 1843.

He continued to fight with his friends from the academy against the liberal bourgeoisie, of which his father was a part, and the Tribune of the plebs James Fazy, who were trying to definitively suppress the old system of patricians in the canton of Geneva.

It is under the name Simon de Nantua that Töpffer continued his struggle in "print literature" in Albert's Story in which he caricatures his political adversary James Fazy as Albert. It is then the first comic used in politics.

This struggle ended with the victory of the liberals after the revolution of 1846, the year of Töpffer's death.

The inventor of comics

The notion of the inventor of the comic is controversial, an art is not a technical process. However, the unprecedented nature of the stories in images that Töpffér began to create in 1827, this new way of articulating text and images assembled in sequences, and above all the perception that the author had done something new, the premonition he had that other people would use this unpublished mode of expression the source generally considered to be the first western comic book author.

Although Töpffér was highly influenced in his staging by theater (the characters are generally represented in full shot, as if facing an audience), and by the narrative in his texts (which articulate the vignettes), his stories are not They are simple illustrated novels because "The verb-iconic components of the narration are inseparable" without the drawing, the text would not make sense, but the latter helps to facilitate the understanding of the story. Far from being a simple juxtaposition of text and image, what makes them interesting is their mixed character (narration-illustration), and it is enough to characterize it as a comic, although the narration is still strongly attached to the text.

Comics are often seen as an art that crosses literary writing and graphic writing. This is also the vision of the inventor of the comic that Töpffer describes in the preface to The Story of Mr. Jabot: « This little book is of a mixed nature. It consists of autographed drawings to the line. Each of these drawings is accompanied by one or two lines of text. The drawings, without the text, would have an obscure meaning; the text, without the drawings, would mean nothing. The whole united forms a kind of novel so original that it does not remind more of a novel than of anything else.»

In April 2021, the jury for the Eisner Awards, the highest American award for comics, posthumously inducts Töpffér into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame.

Author of satires

In the article that consecrated Töpffér, Thierry Groensteen evoked a ≪typology of ridicule about eight heroes of his stories.≫.. In the tradition of the great satirical authors (from Juvenal to Boileau), Töpffér takes I like to observe men to better highlight their defects. ≪Of all times (my father's and mine) we have frequented public squares, crossroads; (...) it is the tendency of all those who like to observe their fellow men, delight in the numerous encounters, in relation to one another, and surrender to an observer who does not notice, who does not question, the secret of their motives, their feelings or their passions.≫

≪Histoire de monsieur Jabot≫ (History of Monsieur Jabot, 1833, drawn in 1831), inspired by The bourgeois gentleman, stages ≪a sort of buffoon foolish and vain who, to enter the noble world, clumsily imitates its forms≫. In ≪Histoire de monsieur Crépin≫ (History of Mr. Crepin, 1837, drawn in 1827) Töpffér mocks the pedagogy of the system, parading ineffective precepts whose methods are always based on a single principle. The succession of teachers is added to a progression towards the absurd, the last pedagogue presents an educational system based on the number of bumps present on the skull of his students. Les Amours de monsieur Vieux Bois (The Loves of Monsieur Vieux Bois, 1837, drawn in 1827) is a variation on the theme of loving rejection; Monsieur Pencil (Mr. Pencil, 1840) about the blindness of artists, scholars and politicians imbued with themselves.

« Histoire d'Albert » (History of Albert, 1845, drawn in 1844), directed directly against James Fazy, founder of the Radical Party, is the only history of Töpffér that he did using references to the politics of the time; Albert is an amateur getting rich based on a newspaper who puts Geneva to fire and blood. Töpffer is introduced into his story under the pseudonym Simon de Nantua. The keys to interpretation are transparent: Simón, the perfect opposite of Albert, crosses him on page 30 and tries to return him to the correct path. The other two comics published during his life, less satirical, still present ridiculous characters: Docteur Festus (Doctor Faustus, 1840, drawn in 1829) presents the journey behind the back of a mulet accompanied by a teacher as an instruction, pretext of a succession of bizarre adventures while Histoire de monsieur Cryptogame (History of Mr. Cryptogram, 1846, drawn in 1830) allows him to put himself back on the scene of frustrated love. Monsieur Trictrac (published in 1937 but made in 1830) is a charge on the medical establishment, which recognizes Trictrac as particularly changed by the different people who take his place as he sets off in search of sources. of the Nile.

His favorite targets, law enforcement and savants, were already highly prized by cartoonists: using the Archetype allows Töpffer to create more believable, and even more amusing, stories. His comedy, based on accumulation, degraded to the absurd, linked to a very high narrative pace, and above all the error in the interpretation of signs linked to classic comedy. If the methods are classic, they are also renewed by their application in new art: the intersection of sequentiality with a loose, caricatured drawing allows an impression of incoherence to be increased. The audacity of the page setting shows Töpffer's great facility with an art that he has just created, however, allowing the author to create his own humor for the comic. As a witness, plate 24 of Albert's story

Success, plagiarism and influence

Of the first handwritten versions of his comics, with everything still unpolished, they met with enormous success: Goethe declared: «This is really a lot of fun! This is dazzling with spirit brilliance! Each of the pages are incomparable. If he chooses, in the future, a slightly less frivolous subject and then makes it more concise, he would do things beyond imagination. »

His carefully redrawed manuscripts were published in albums, run of 500 copies from 1833 for the Swiss Cherbuliez editions, were regularly republished in Töpffer's lifetime, and were quickly forged: the Parisian Aubert editions of Charles Phillipon Owner of Le Chavari, he published clumsily redrawn Jabot, Crepin, and Vieux Bois in 1839. Cham, having Aubert as editor, appeared the same year as his first comic strips Histoire de Mr Lajaunisse and Histoire de Mr Lamélasse, directly inspired by Töpffer's work. It is this same Cham who, at the request of Töpffer's cousin, Jacques-Julien Dubochet and editor of L'Illustration, the first fully illustrated French current affairs magazine, woodcut for the pre-publication of 25 from January to April 19, 1845 of the History of Mr. Cryptogame. It was not until 1860 that the correct editions appeared in France, scrupulously redrawed by Françoise Töpffer, her son, in Garniere Fréres, who had a decisive influence on the great authors of the century XIX as Christophe. In Germany, a bilingual edition comprising six titles was published in 1846, laudably introduced by Frederich Theodore Vischer, revitalizing German illustrated history, embodied then by (Struwwelpeter d'Heinrich Hoffmann, 1845), and giving the idea of making comics to local authors such as Adolph Schrödter who drew in 1849 Herr Piepmeyer on the stage of a deputy, Johann Detmold, directly inspired by the History of Albert. It is Schrödte who in turn inspires Wilhelm Busch for Max und Moritz.

By the end of his life, Töpffer was highly reputed and known throughout Europe: Mr. Cryptogame was published in 1846 in Great Britain, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Germany. Töpffer was translated in the United States, beginning in 1842 in a supplement by Brother Jonathan in Monsieur Vieux Bois called Obadiah Oldbuck. According to historian Robert Beerbohm, who in 2000 fell on a copy of 'Obadiah Oldbuck, this was the first comic published in the United States. This edition was, in fact, a pirated one, since it appeared without Töpffer's notice. The same goes for other of his works published in that period. At the beginning of the 20th century, Töpffer was already universally known, witness to this the adaptation of The loves of Mr. Vieux Bois in animation in 1920. Even so, he was gradually forgotten, the comic took a different direction more rigid, more academic (as in the case of Christophewho claimed, however, a direct inspiration from Töpffer, or from Joseph Pinchon) and was not rediscovered until the early 70's of that century.

The first theoretician of a new art

Literary critic, scholar, Töpffer immediately became aware of having created a new art. He wrote in 1833 in the preface to the History of Mr. Jabot: «This little book is of a mixed nature. This is made up of a series of autographed drawings. Each of his drawings is accompanied by one or two lines of text. The drawings, without text, would only have an obscure meaning; the text, without the drawing, would mean nothing. The integrated whole forms a much more original kind of novel that is no less reminiscent of a novel than of anything else.

Töpffer, as a result of launching a contest (the program), begins in January and April 1836, delivering his reflections on popular imagery in 48 pages to emphasize its educational role. The precocity of his opinions are particularly surprising as well as the relevance of his analysis. These preceded Champfleury's History of Popular Imagery by more than thirty years.

In 1842 he published a news item on the technique of autography. This small volume in Italian octavo format consists of 24 plates of autographed drawings, half being landscapes, the other half portraits, announcing his physiognomy essays, to demonstrate the true artistic qualities of this reproduction technique.

Considered the first comic book theorist, in 1845 he published his Essay on Physiognomy, the first theoretical work on what was still called comics or comic strips. Topffer's theory is based mainly on the inseparability of text and drawing (the comic is a mixed genre and not composed); the ease of access of the comic in relation to literature, thanks to its quality of being clear and concise; the awareness of the future development of the comic; the centrality of the character in the story; the need for a spontaneously autographed line drawing, as opposed to relief (engraving) and color (painting), in order to offer the greatest possible narrative dynamism, hence the importance of physiognomy, and the need to know how to build expressive scenes. In his Essay on Physiognomy he adopts the exact counterpart of Johann Kaspar Lavater because "physiognomy or the art of knowing men" is "the science, the knowledge of relation that unites the exterior to the interior, the visible surface to the invisible one that it covers ». Töpffer seeks in physiognomy the means to draw types of characters that clearly express their personality. Because a picture story speaks directly to the eye, the essence of storytelling evolution must be readable through facial features, says Groensteen.

Contenido relacionado

The Truman Show

Jose Enrique Rodo

Peruvian Literature