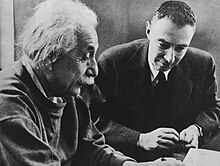

Robert oppenheimer

Julius Robert Oppenheimer (New York, United States, April 22, 1904-Princeton, New Jersey, United States, February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist of Jewish origin and professor of physics at the University of California at Berkeley. He is one of the people often referred to as the "father of the atomic bomb" due to his prominent involvement in the Manhattan Project, the project that succeeded in developing the first nuclear weapons in history, during World War II. The first nuclear bomb was detonated on July 16, 1945 at the Trinity Test in New Mexico, United States. Oppenheimer would later state that the words of the Bhagavad Gita came to mind: "Now I have become death, the destroyer of worlds." Oppenheimer always expressed regret at the deaths of innocent victims when nuclear bombs were dropped. against the Japanese at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

After the war, he served as chief adviser to the newly created United States Atomic Energy Commission and used his position to advocate for international control of nuclear power, prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons, and curb the arms race between United States and the Soviet Union. After incurring the ire of numerous politicians for his public views, he eventually had his security clearances withdrawn, lost access to his country's secret military documents, and was stripped of his direct political influence during a highly publicized hearing in 1954. In that decade, the United States lived under McCarthyism and all those people suspected of sympathizing with communism or simply being dissidents were persecuted by the government; Oppenheimer was able to continue writing, working on physics, and lecturing. Nine years after the hearing, Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson awarded him the Enrico Fermi Prize respectively as a gesture of rehabilitating his figure.

Oppenheimer achieved notable achievements in the field of physics, such as the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. He also worked on the theory of electrons and positrons, the Oppenheimer-Phillips process of nuclear fusion, and the first prediction of tunneling. Together with his students, he made important contributions to the modern theory of neutron stars and black holes, as well as to quantum mechanics, quantum field theory, and cosmic ray interactions. As a teacher and promoter of science, he is remembered as one of the founders of the American school of theoretical physics that gained worldwide prominence in the 1930s. After World War II, he also served as director of the Institute for Advanced Study from Princeton.

Studies

Robert Oppenheimer was born in New York on April 22, 1904, the son of Julius S. Oppenheimer (a wealthy textile importer who had emigrated from Germany to the United States in 1888) and Ella Friedman (an artist). He studied at the Ethical Culture Society School. Throughout his life he was a very versatile student, with a good aptitude for both the sciences and the arts. He entered Harvard University a year late due to a bout of colitis. During that year, he traveled with a retired literature professor to recuperate in New Mexico. He returned well recovered making up for his one year delay by graduating summa cum laude in just three years in Chemistry.

During his studies at Harvard, Oppenheimer became interested in experimental physics in the Thermodynamics course taught by Professor Percy Bridgman, and since there were no world-class experimental physics centers in the United States at the time, it was suggested to him continue their studies in Europe. He was accepted as a graduate student at Ernest Rutherford's famous Cavendish Laboratory. Oppenheimer's lack of skills in the laboratory made him realize that his forte was theoretical physics, not experimental. In 1926 he left for the University of Göttingen, in Germany, to study under the supervision of Max Born. Göttingen was then one of the leading centers for theoretical physics in Europe. Oppenheimer made friends there with other famous students, such as Paul Dirac, and at the age of twenty-two he obtained his doctorate. Oppenheimer was known to be a very fast learner.

Teaching

In Göttingen, Oppenheimer published many important contributions to the then newly developed quantum mechanics, particularly a well-known paper on the so-called Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which separates nuclear motion from electronic motion in the mathematical treatment of molecules. In September 1927, he returned to Harvard as a young expert in mathematical physics and a member of the American National Research Council, and from early 1928 he was a professor at the California Institute of Technology (Cal. Tech.). While there, he received multiple offers from various universities and accepted an assistant professorship in physics at the University of California at Berkeley, compatible with his position at Cal. Tech. In his words, Berkeley 'was a desert, & # 34; and paradoxically a place full of opportunities. Each spring, Oppenheimer taught at Cal. Tech. to keep up with research in his area. Oppenheimer became friends with Linus Pauling and they had planned to work together on research, but this never came to fruition.

Before beginning to teach at Berkeley, Oppenheimer suffered from tuberculosis, and had to spend a few weeks on a ranch in New Mexico with his brother. Later he would acquire that ranch and used to say that physics and the desert field were his two great loves; loves that were later combined when choosing the Los Alamos site for the installations of the pump project. After a period of recovery, he returned to Berkeley, where he led a generation of physicists who admired him for his intellectual height and his broad interests. The Nobel Prize in Physics Hans Bethe would later say about him:

Probably the most important ingredient that Oppenheimer added to his classes was his exquisite taste. He always knew what the major problems were, as noted in his selection of topics. He really lived those problems, looking for a solution and communicating his concern to the group.Hans Bethe

Oppenheimer was friends with and worked closely with experimental physicist Ernest O. Lawrence and his group of pioneering cyclotron work, helping to understand the new experimental data they were producing with their equipment in the Radiation Laboratory.

California

Oppenheimer is credited with founding the American school of theoretical physics; he was reputed for his eclecticism, his interest in languages, Eastern philosophy and the eloquence and clarity with which he thought. But he also had a turbulent life, suffering from periods of depression. He once wrote to his brother: I need physics more than friends . He was a tall, thin man, a continuous smoker, who sometimes forgot to eat during his individual concentration periods. Some of his friends thought that Oppenheimer had self-destructive tendencies and on several occasions his colleagues worried about his melancholy and insecurity. As a student at Cambridge, he once took a vacation to Paris to meet his friend Francis Ferguson and as she was recounting his frustration with experimental physics she suddenly approached him and tried to strangle him. Ferguson easily stopped him, but the incident convinced Ferguson of his deep psychological problems. Oppenheimer developed numerous conditions, probably in an attempt to convince those around him and possibly himself of his own importance. He had a strong power of conviction in his personal treatment, but he was very shy in public. His colleagues tended to be divided into two camps: Those who admired his genius and those who saw his actions as pretentious and insecure. His students were almost all in the first group, usually inadvertently adopting gestures and even his teacher's way of walking and talking.

Oppenheimer did important research in astrophysics, nuclear physics, spectroscopy, and quantum field theory. His best-known contribution, made as a graduate student, is the aforementioned Born-Oppenheimer approximation. He also made important contributions to the theory of cosmic ray showers and did work that later led to descriptions of quantum tunneling. In the late 1930s, he was the first to write papers suggesting the existence of what are now called black holes. In 1930 he wrote a paper that essentially predicted the existence of the positron (which had been postulated by Paul Dirac), a formulation which he did not carry through, however, due to his skepticism about the validity of Dirac's equation. Even for experts, Oppenheimer's works were considered difficult to understand. Oppenheimer was fond of using elegant but extremely complicated mathematical techniques to demonstrate physical principles. In some cases some mathematical errors have been found, probably due to precipitation.

Many have felt that Oppenheimer's discoveries were not commensurate with his abilities and talents. They consider him an exceptional physicist, but they do not place him among the greatest, those who have shaped the frontiers of knowledge. One possible reason for this was his widely varying interests, which prevented him from fully focusing on any single field long enough to produce major breakthroughs. His colleague and confidant Isidor Rabi later gave the following interpretation:

Oppenheimer had a very complete formation in those fields that fall outside the scientific tradition, as his interest in religion, particularly in the Hindu religion, which became a kind of mystery feeling that surrounded him. He saw physics clearly, looking at what had already been achieved, but at the limit he tended to feel that there was much more mystery than he really had... he moved away from the strong and crude methods of theoretical physics towards a mystical feeling of wide intuition.Isidor Rabi

Despite this, many (including physicist Luis Álvarez) have suggested that if Oppenheimer had lived long enough to see his predictions supported by experiments, he would have won a Nobel Prize for his work on gravitational collapse, related to neutron stars and black holes.

Political positions

During the 1920s, Oppenheimer kept aloof from world events. At one point he claimed not to have learned of the financial crisis of 1929 until the time (Oppenheimer personally did not have many financial concerns due to his family heritage). It was only by meeting Jean Tatlock, daughter of a Berkeley literature professor, in 1936, that he became interested in politics. Like many intellectuals of the 1930s he supported communist ideas and, thanks to the capital he inherited from him (more than $300,000, a huge amount at the time), he was able to finance many leftist political efforts. Most of these contributions were dedicated to financing pro-Republican fundraisers in the Spanish Civil War and other anti-fascist activities. He never officially joined the Communist Party of the United States (his brother Frank did, contrary to Robert's opinion), although historians such as Gregg Herken claim to have found evidence that Oppenheimer had relations with the Communist party in the decades. 1930s and 1940s. In November 1940, he married Katherine Puening Harrison, a "radical" from Berkeley, and in May 1941 they had Peter, his first child.

Involvement in the development of the atomic bomb

The Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was the code name for a research project carried out during World War II by the United States with partial assistance from the United Kingdom and Canada. The ultimate goal of the project was the development of the first atomic bomb. Scientific research was led by Oppenheimer while security and military operations were handled by General Leslie R. Groves. The project was carried out in numerous research centers, the most important being the Manhattan Engineering District located in what is now known as Los Alamos National Laboratory, in New Mexico.

The project brought together a large number of eminent scientists (physics, chemistry, computer science). Given that after the experiments in Germany prior to the war it was known that the fission of the atom was possible and that the Nazis were already working on their own nuclear program, it was not difficult to gather all those brilliant minds with the aim of obtaining the bomb before the Germans.[citation needed]

In the race for the nuclear bomb, the Germans had the Uranium Project and the Soviets had Operation Borodino.

Los Alamos

When World War II began, Oppenheimer became heavily involved in efforts to develop an atomic bomb that already took up much of the time and equipment at Ernest Lawrence's Radiation Laboratory at Berkeley. In 1941, Lawrence, Vannevar Bush, Arthur Compton, and James Conant were trying to get the Uranium Committee established by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1939 to assign them the bomb project, because they felt it was progressing too slowly. Oppenheimer was invited to take up the work of calculating neutrons, a task he faced with full vigor, giving up what he called his "leftist wanderings" to pursue what he now considered his duties (although he still had many friends and very radical students). When the US military was given jurisdiction over the bomb effort, now christened the Manhattan Project, project manager Leslie R. Groves (who had recently finished directing the construction of the Pentagon) appointed Oppenheimer chief scientific officer. of the project, an action that surprised many. Groves knew of the potential security problems tied to Oppenheimer, but considered him the best man to lead a diverse team of scientists and that he would not be affected by his previous political leanings.

One of Oppenheimer's first actions was to host a summer school on bomb theory at the project's Berkeley facility, bringing together European physicists and his own students. This group, which included Robert Serber, Emil Konopinski, Felix Bloch, Hans Bethe, and Edward Teller, worked out what needed to be done, and in what order, to build the bomb. When Teller raised the remote possibility that the bomb would generate enough heat to ignite the atmosphere (an event Bethe soon proved impossible), Oppenheimer was so concerned about the possibility that he met with Arthur Compton in Michigan to discuss it. At the same time, project research was going on at many universities and in many laboratories across the country, posing problems for both the safety and cohesion of the project. Oppenheimer and Groves decided they needed a secret, centralized laboratory. Looking for a site, Oppenheimer proposed a region of New Mexico not far from his ranch. On a plateau near Santa Fe, the capital of New Mexico, the Los Alamos laboratory was quickly built, a banal group of barracks surrounded by mud. There Oppenheimer managed to assemble a group of the most brilliant physicists of the time, including Enrico Fermi, Richard Feynman, Robert R. Wilson, and Victor Weisskopf as well as Bethe and Teller. Oppenheimer's second daughter, Katherine (called Toni), was born there in 1944.

Oppenheimer was credited for his mastery of all scientific aspects of the project and his efforts to manage the inevitable cultural conflicts between scientists and the military. He was the image of the project for his scientific colleagues and he exercised his role as director with great poise. Victor Weisskopf put it this way:

He didn't run from the central office. He was intellectually present and even physically in every decisive step. He was present in the laboratory or seminar rooms, when a new effect was measured, when a new idea was conceived. It was not so much because of the ideas he provided sometimes, but his main influence came from something else. It was his continued and intense presence, which produced in all of us a sense of direct participation; he created that unique atmosphere of enthusiasm and defiance that prevailed throughout his period.Victor Weisskopf

A great uproar was organized (quickly silenced by the military authorities) when, in 1947, in an interview about his work, when asked why the uranium bomb (like the one in Hiroshima) had not been tested previously (the one in the Los Alamos desert was made of plutonium, thanks to the Von Ardenne triggers captured in a German submarine), he replied

There was nothing to prove, the Germans had already done it before, we just had to use it and that's it.

Meanwhile, Oppenheimer was under investigation by the FBI and the Manhattan Project's internal security department for his previous leftist associations. He was also followed by an FBI agent during an unexpected trip to California in 1943 to find his ex-partner, Jean Tatlock. In August 1943, Oppenheimer reported to Project security agents that one of his friends with communist connections had solicited nuclear secrets from three of his students. Pressed on the matter in subsequent meetings with General Groves and security agents, he identified his friend as Haakon Chevalier, a Berkeley professor of French literature. Oppenheimer would be asked for statements related to the "Chevalier incident" and often gave conflicting and misleading statements, telling Groves that Chevalier had contacted only one person, and that person was his brother, Frank. But Groves, aware of Oppenheimer's importance to the Allies' goals, could not remove him from the project despite this suspicious behavior.

Trinity

The collective work of the scientists at Los Alamos had its first success in the first nuclear explosion near the town of Alamogordo (New Mexico) on July 16, 1945. Oppenheimer named the test Trinity (Trinity); he later explained that it was based on a line by the poet John Donne (1572-1631). According to historian Gregg Herken, this name may have been an allusion to Jean Tatlock, who introduced him to Donne's work when they were a couple in the 1930s. Tatlock had committed suicide only months earlier, much to Oppenheimer's dismay. He later recalled that while witnessing the explosion, he thought of a verse from a Hindu text, the Bhagavad-Gita:

If the splendour of a thousand suns shone into unison in heaven, it would be like the splendor of creation...

However, another verse he remembered got stuck in his mind:

Now I have become Death, Destroyer of Worlds.

According to his brother, he immediately exclaimed simply —It worked. The news of the successful test was urgently communicated to President Harry S. Truman, who could use this information to strengthen his position at the Potsdam Conference on the future of post-war Europe, which would soon take place..

Japan

Once the weapon was developed, and with the material seized in Germany, the scientific administrators disagreed as to whether and how to use it. Initially, Lawrence opposed the use of the bomb against living people, arguing that a mere demonstration would be enough to convince the Japanese government that it would be useless to continue the war. Oppenheimer and many of the military advisers strongly disagreed with this assessment. Oppenheimer feared that if it were announced where such a demonstration might occur, the enemy might move prisoners of war or other human shields into the region. According to other physicists, including Teller and Leó Szilárd, using the weapon in a civilian area would be an atrocity. A petition was circulated at the Los Alamos and Oak Ridge laboratories pleading that the bomb not be used as immoral and unnecessary. Oppenheimer opposed the request and warned Szilard and Teller that they should not hinder the project, but they did not back down, and Oppenheimer gave Leslie Groves a note of the letter addressed to Harry S. Truman, who orders it intercepted, so this would never reach its addressee. Still, it's not clear how much the US government and military cared about the scientists' opinions about the weapon they had created.

On August 6, 1945, the Little Boy uranium bomb was dropped on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, the plutonium bomb Fat Man was dropped on Nagasaki. The bombs killed hundreds of thousands of civilians instantly and many more in the days and months that followed.

The pride Oppenheimer felt after the successful Trinity test was soon replaced by guilt and horror, though he never said he regretted making the weapon. On a subsequent visit with President Harry S. Truman, he inquired about the time it would take for the Soviets (& # 34; the Russians & # 34;) to obtain the bomb, to which he replied that he did not know.. The American president for his part snapped "Never!", before a surprised Oppenheimer. The scientist replied to himself that he felt that he had "his hands stained with blood", to which the president was upset. Once the place was abandoned, the president ordered his assistant that he did not want to see "this bastard" again.

During Robert Oppenheimer's only visit to Japan after the war, in 1960, a journalist asked him if he felt any remorse about developing the bomb. He joked Oppenheimer, “It's not that I don't feel bad. It's just that I don't feel worse today than I did yesterday.

Post-war Activities

Suddenly, Oppenheimer became a national spokesman for science and emblem of a new kind of technocratic power. Nuclear physics became a major force as all the world's governments began to realize the strategic and political power associated with nuclear weapons and their dire consequences. Like many scientists of his generation, he opined that the safety of nuclear bombs would come only from some kind of transnational body (like the newly created United Nations) that could initiate a program to stop a nuclear arms race.

Atomic Energy Commission

As soon as the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was created in 1946 as a civilian agency controlling nuclear research and weapons, Oppenheimer was appointed chairman of its General Advisory Committee. General, GAC) and resigned from his position as director of Los Alamos. From that position he gave advice on various nuclear issues, including project sponsorship, laboratory construction, and even international policy - although GAC advice was not always put into practice. The 1946 Baruch Plan, which called for the internationalization of atomic power, stemmed in part from Oppenheimer's views, though to his dismay it included many additional elements that made it clear that its goal was simply to prevent the Soviet Union from getting a bomb of its own, instead of fostering a lasting international control mechanism. The Soviet Union rejected the plan, not surprisingly to observers, and Oppenheimer realized that an arms race was inevitable due to mistrust between the US and the USSR.

In 1947 he left Berkeley because of wartime problems with the administration, he said, and became director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. He later held Albert Einstein's former position of high professor of theoretical physics.

While still chair of the GAC, Oppenheimer lobbied vigorously for international arms control and patronage of fundamental science, and attempted to influence policy against a heated arms race. When the government was debating whether to undertake a crash program to develop a weapon based on nuclear fusion - the thermonuclear bomb - Oppenheimer initially recommended against it, even though he had favored developing such a weapon in the early days of the Manhattan Project. He was partly driven by ethical reasons, believing that such a weapon could only be used against civilians, causing millions of deaths. But it was also driven by practical reasons. Since no feasible design for a thermonuclear bomb existed at the time, Oppenheimer was of the opinion that resources would be better spent creating a large fission weapons force. Despite his advice, President Harry Truman announced a crash program after the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb in 1949. Oppenheimer and fellow GAC opponents of the project, most notably James Conant, felt personally rejected and considered withdrawing from the project. committee. They stayed, although their views on the thermonuclear bomb became well known.

In 1951, however, Edward Teller and mathematician Stanislaw Ulam developed what would become the Teller-Ulam configuration for a thermonuclear bomb. This new design seemed feasible, and Oppenheimer changed his mind about developing the weapon. As he later said:

The program we had in 1949 was a horrendous thing that could well be deduced that it did not make too much technical sense. That's why it was possible to argue that something like that was not wanted even if it could be. The program in 1951 was technically so attractive that it could not be discussed. The issues were already only the military, the politics, and the humanitarian problems of what was to be done with it once it was achieved.

The first true thermonuclear bomb, named Ivy Mike, was tested in 1952 and produced 10.4 megatons, a force 650 times greater than the weapons developed by Oppenheimer during World War II.

Security audit

In his role as political adviser, Oppenheimer made many enemies. The FBI led by J. Edgar Hoover had been following his activities since before the war, when he showed communist sympathies as a radical professor. They were eager to provide Oppenheimer's political and professional enemies with incriminating evidence of communist ties.

These enemies included Lewis Strauss, an AEC commissioner who had long harbored a grudge against Oppenheimer, both for his anti-hydrogen bomb activity and for humiliating him before Congress some years earlier. Strauss and Senator Brien McMahon, author in 1946 of the Atomic Energy Act, seconded by Edward Teller, the indictment's framer, urged President Eisenhower to revoke Oppenheimer's security clearance. This followed controversy over whether some of Oppenheimer's students, including David Bohm, Joseph Weinberg, and Bernard Peters, had been communists when they had worked with him at Berkeley. Oppenheimer's brother, Frank Oppenheimer, was forced to testify before the Committee on Un-American Activities, where he admitted to having been a member of the Communist Party in the 1930s, but refused to name other members. As a result, Frank was fired from his university position, and unable to find work in the physics field, he ended up as a rancher in Colorado.

In 1953, Oppenheimer was accused of being a security risk and President Eisenhower asked him to resign. Oppenheimer refused, requesting an audit to assess his loyalty, and in the meantime have his security clearance placed on hold. Public appearances that followed focused on Oppenheimer's past communist ties and his association during the Manhattan Project with scientists suspected of being disloyal or communist. One of the key elements in this process was Oppenheimer's earlier testimony about his friend Haakon Chevalier, which he himself confessed to fabricating. In fact, Oppenheimer had never spoken to Chevalier about it, and the testimony had led to Chevalier losing his job. Edward Teller, with whom Oppenheimer had disagreed about the hydrogen bomb, testified against him, drawing the ire of the scientific community and the virtual expulsion of Teller from academic science. Many leading scientists, as well as prominent government and military figures, testified on Oppenheimer's behalf. The inconsistencies in his testimony and his erratic behavior in his appearances convinced some that he was untrustworthy and a potential security risk. Oppenheimer's security clearance was revoked.

During his appearance, Oppenheimer willingly testified about the left-wing behavior of many of his fellow scientists. Historian Richard Polenberg has speculated that if Oppenheimer's credential had not been revoked (he would have expired in a matter of days anyway), he would have been remembered as one who "gave names"; to save his reputation, a "snitch". As it happened, Oppenheimer was seen by most of the scientific community as a martyr to McCarthyism, an eclectic liberal who was unfairly targeted by warmongering enemies, a symbol of the substitution of militarism for academic scientific creativity.

Institute for Advanced Study

Deprived of political power, Oppenheimer continued to teach, write, and work on physics. He toured Europe and Japan, giving talks on the history of science, the role of science in society, and the nature of the universe. In 1963, at the urging of many of Oppenheimer's political friends who had risen to power, President John F. Kennedy awarded Oppenheimer the Enrico Fermi Prize as a gesture of political rehabilitation. Edward Teller, winner of the award the previous year, had also recommended that Oppenheimer receive it. Just over a week after Kennedy's assassination, his successor, President Lyndon Johnson, presented the award to Oppenheimer, "for contributions to theoretical physics as a teacher and originator of ideas, and for leadership of the Los Angeles laboratory. Alamos and the atomic energy program during critical years". Oppenheimer told Johnson: "I think it is possible, Mr. President, that it took some charity and some courage to give this award today. This could mean a good omen for the future of all". The rehabilitation implied by the award was only symbolic, as Oppenheimer continued to lack a security clearance, and was to have no effect on official policy, but the award came with a $50,000 endowment.

In his later years, Oppenheimer continued his work at the Institute for Advanced Study, bringing together intellectuals of the best of his abilities and from various disciplines to answer the most pertinent questions of the present day. His lectures in the United States, Europe and Canada were published in many books. Regardless, he thought the effort had little effect on royal politics.

Last years

After the 1954 security audit, Oppenheimer is said to have been "like a wounded animal" and began to retreat to a simpler life. In 1957 he purchased a piece of land on Gibney Beach, on the island of Saint John, in the United States Virgin Islands. He built a simple vacation home, where he would spend vacations, usually several months out of the year, with his wife Kitty. Oppenheimer also spent considerable time sailing with his wife. On his death, the property was inherited by his daughter Toni, who bequeathed it "to the town of St. John as a public park and recreation area." Currently, the Virgin Islands government has created a community center there, which can be leased. The beach is colloquially known to this day as "Oppenheimer Beach".

Robert Oppenheimer died of throat cancer in 1967. His funeral was attended by many of his scientific, political, and military associates. He was cremated and his ashes were scattered in the Virgin Islands.

Eponymy

In addition to the different postulates of nuclear physics that bear his name, one must:

- The moon crater Oppenheimer bears this name in his memory.

- The asteroid (67085) Oppenheimer also commemorates its name.

Contenido relacionado

Carl Wilhelm Wirtz

Ildefonso Cerdá

February 4