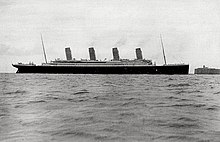

Rms titanic

The RMS Titanic was a British ocean liner, the largest passenger ship in the world at the end of its construction, which sank in the waters of the Atlantic Ocean during the night of April 14 and early morning of April 15 1912, while on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York, after colliding with an iceberg. In the sinking, 1,496 of the 2,208 people who were on board died, making this catastrophe one of the largest shipwrecks in history that occurred in peacetime.

Being built between 1909 and 1912 at the Harland & Wolff of Belfast, Titanic was the second ship in a trio of large ocean liners (the first being RMS Olympic and the third being HMHS Britannic) owned by the White Star Line shipping company, known as the Olympic class.

His passengers included some of the world's wealthiest people, as well as hundreds of Irish, British and Scandinavian immigrants seeking a better life in North America. The ship was designed to be the ultimate in luxury and comfort, featuring a gymnasium, indoor pool, library, fine dining, and opulent cabins for first-class travelers, as well as a powerful telegraph station available for passenger use. and crew. Added to all this, the ship was equipped with some advanced security measures for the time, such as its hull bulkheads and remote-activated watertight doors. Other measures, however, proved insufficient, as she only carried lifeboats for 1,178 people, just over half of those aboard on her maiden voyage and a third of her total capacity of 3,547 people.

After leaving Southampton on April 10, 1912, the Titanic called at Cherbourg, France, and Queenstown (present-day Cobh), Ireland, before heading out into the Atlantic Ocean. At 11:40 p.m. on April 14, four days after setting sail and about 600 km south of Newfoundland, the ship collided with an iceberg. The collision opened several hull plates on the starboard side below the waterline, along five of her sixteen watertight compartments, which began to flood. Over two and a half hours the ship gradually sank through her bow section as her stern rose, and in this time several hundred passengers and crew were evacuated in lifeboats, almost none of which were occupied until their completion. Maximum capacity.

A very large number of men perished due to the strict lifesaving protocol followed in the evacuation process, known as "Women and Children First." At 2:17 on April 15, the ship it broke in two and sank with hundreds of people still on board. Most of those who remained floating on the surface died of hypothermia, although some managed to be rescued by lifeboats. The 712 survivors were picked up by the ocean liner RMS Carpathia at 04:00.

The sinking of the Titanic shocked and outraged the entire world due to the high number of fatalities and the mistakes made in the accident. Public inquiries in the United Kingdom and the United States led to major improvements in maritime safety and the creation in 1914 of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS). that still governs maritime safety today. Many of the survivors, who lost their entire estate in the tragedy, were helped through public charity, but others, such as White Star president J. Bruce Ismay, were accused of cowardice for their premature abandonment of the ship and condemned to social ostracism.

The wreck of the Titanic was discovered on September 1, 1985 by American oceanographer Robert Ballard at the bottom of the North Atlantic, at a depth of 3,784 m. The remains are badly damaged and suffer progressive deterioration, but since its discovery thousands of objects from the ship have been recovered and these are exhibited in many museums around the world.

The Titanic is perhaps the most famous ship in history and its memory is kept very alive thanks to numerous books, songs, films, documentaries, exhibitions, various works of historians and memorials.

Background

In 1907, Joseph Bruce Ismay, president of the White Star Line shipping company, and Lord William Pirrie, president of Harland & Wolff, decided to build a trio of large ocean liners to compete with the new ships of rival shipping company Cunard Line. These ships, baptized as Lusitania and Mauretania, had become the largest, most luxurious and fastest ocean liners in the world, winning at certain moments in their careers the Blue Band, an award for the fastest crossing.

The trio of vessels planned by Pirrie and Ismay had been designed to outperform Cunard's vessels, as well as their European rivals, in terms of size, safety and elegance, as both men agreed it would be more It is prestigious to bet on these fields instead of speed. After deciding on the design of the ships, the names were chosen: Olympic, Titanic and Gigantic (the latter changed to Britannic), in reference to the three races of Greek mythology: the Olympian gods, the titans and the giants.

The project to build the three vessels was carried out at the offices of Harland & Wolff in Belfast, Northern Ireland.The designers were Pirrie himself, his nephew Thomas Andrews, construction manager and head of the design department at Harland & Wolff, and his brother-in-law Alexander Carlisle, chief designer and general manager of the shipyard Carlisle's responsibilities included decorations, equipment, safety devices and all general arrangements, including the implementation of an efficient davit system for the lifeboats. However, Carlisle left the project in 1910, while the Olympic and Titanic were still under construction, when he became a shareholder in Welin Davit & Engineering Company Ltd. (the company that manufactured the davits), leaving Andrews solely responsible for the projects. It is speculated that this occurred because the engineer's original idea was to fit 66 lifeboats aboard the davits. ships, but his ideas and claims were rejected by both Ismay and Pirrie.

The project for the construction of the ships was approved by Ismay on July 31, 1908, when a letter of agreement was signed with the shipyards. No formal contract was signed because White Star and Harland & Wolff had a very close and strong relationship that went back decades. Pirrie saw the importance of the ships and commissioned the shipyard's official photographer, Robert Welch, to take images of the works to record their progress.

The quality of the ships was not neglected and the best materials available at that time were used for their construction.

Construction

Final plans were completed in the fall of 1908 and the materials needed for construction were commissioned by Harland & Wolff. The Titanic was built alongside hers hers sister, the Olympic. A new 256 m long by 52 m high portico needed to be built to accommodate both vessels, as no other existing structure was large enough for the job.

| ||||||

| Advance the construction of the Titanic from the uprising of the porch, until April 1911 (See the full gallery). |

The Titanic was built with the construction number 401. Its construction was financed by the American businessman J. P. Morgan and his company International Mercantile Marine Company, and began on March 31, 1909, with a total cost of 7, 5 million dollars at the time (about 172 million dollars at current exchange rates).

Because the Olympic was the first of the ships to be built, her hull was painted a light gray color for her launching, in order to allow greater sharpness and detail in the photographs. In contrast to her sister ship, the Titanic was built with her hull painted black.

Construction of its structure progressed at a good pace, and it was completed in early 1911. Its hull consisted of approximately 2,000 steel plates measuring three meters long by two meters wide, with a thickness between 2.5 and 3.8 cm. Those plates were held together by more than 3 million rivets.

Until then, the ship was just a huge empty hull without any internal equipment or installations. The Titanic's hull was launched at 12:13 p.m. on May 31, 1911. More than 100,000 people were present to witness the launch: shipyard officials with their families, Belfast residents, visitors, journalists and some important personalities. coming directly from England. The ship slipped into the water from its slipway with the help of 22 tons of tallow, oil and soap. The ship was not christened in the traditional way (by breaking a bottle of champagne), as it had never been a Harland and Wolff custom, and furthermore Pirrie was of the opinion that this could cause superstitions among the passengers and crew.

| ||||

| Evolution of the different phases of construction from the Titanic booth, in May 1911, to the realization of its maritime tests, on April 2, 1912. |

After its launch, the Titanic stopped with the help of six anchors. Three steel mooring lines, each weighing eighty tons, were attached to the hull and it was towed into a dry dock with the help of five tugboats. White Star journalists and special guests were, after the event, taken to a special luncheon at the Grand Central Hotel. On the menu there were no less than six different main courses and five after-dinner meals. Ismay left lunch early so that he could board the Olympic and participate in her sea trials.

After the launching, the process of outfitting the ship began. More than three thousand professionals (mechanics, electricians, plumbers, carpenters, painters, decorators, etc.) worked from June 1911 to March 1912, equipping the ship with the most recent technologies and naval innovations and installing its sumptuous furniture and decorative elements. During that period, the White Star announced on September 18, 1911 that the Titanic would make its maiden voyage on March 20, 1912.

Meanwhile, on September 20 of that same year, two days after the voyage date was announced, the Olympic ended up colliding with the warship HMS Hawke, for which reason it had to be sent to the Belfast shipyards for damages be repaired. As a consequence, she had to pull the Titanic out of dry dock to allow her brother's repairs to take place. Part of the workers were also temporarily transferred to the Olympic, significantly delaying the fitting out of the interior of its sister ship, as well as its delivery and entry into service, so that White Star was forced to postpone its maiden voyage to the day April 10, 1912. The Titanic returned to her dock in November, when work on the Olympic was completed, and work continued at the same pace as before.

Its four chimneys were installed in January 1912; only three of them, 18.9 m high, were functional; the fourth served solely for ventilation, and was added to give the ship a more impressive appearance.In the following month, her three bronze propellers were placed in their proper places on her; the wing blades were over 7m in diameter and weighed 38 tons, while the center blade was over 5m in diameter and weighed 22 tons.

The outfitting process ended in March 1912 and the ship was registered on the 24th of the same month, with Liverpool as its home port, despite never having sailed in its waters. the Titanic succeeded its sister ship, the Olympic, as the largest ship in the world. This was because, despite the fact that both ships had the same dimensions, the Titanic displaced 1,004 tons more and the size of a ship is measured by tonnage.

Description of the ship

Standard first-class cabins were adorned with white wainscoting, expensive furniture, and other elegant decorations. They only had shared bathrooms that had hot and cold water. There were also electric stoves. In the case of the four most luxurious suites, fireplaces with beautifully built-in electric stoves were used in the living rooms. As a relative innovation in the ships of the time, the Titanic had three elevators for first class and one for second class, She had 370 first class cabins, 168 second class and 297 shared third class cabins.

Boat deck

The lifeboats were located in two groups, one towards the bow and one towards the stern. At the front were twelve boats (six on each side), and towards the stern were eight boats (four on each side), with a total of 20 lifeboats of three different types:

- Bots 1 and 2: wooden chinchorros for emergencies, with capacity for 40 people.

- Lots numbers 3 to 16: made of wood, with capacity for 65 people.

- A, B, C and D boots: folding boats brand Englehardt with capacity for 47 people; these boats had the fabric sides.

With all the boats filled to capacity, a total of 1,178 people could be embarked.

Towards the bow, there was also the command bridge and the first block, which included the officers' rooms, the Marconi radiotelegraphy room, the machines that moved the elevators and six simple first-class rooms. In the walls of this block were circular windows that illuminated the first-class interior rooms on the lower deck.

The second block was made up of the first-class Grand Staircase and the gymnasium. The stairway ran from this deck to E deck; on the upper level there was a glass dome that provided natural light to the staircase throughout its levels by means of skylights on both sides of it. The gym was located on the starboard side, next to the first class entrance. It was equipped with equipment that worked electrically, as well as exercise bikes and other amenities. The place was conditioned for greater comfort and had a wooden panel against the wall of the fireplace space where two figures could be seen: a world map and a cross section of the ship.

Between the second and third fireplaces was the raised ceiling of the general hall and first class reading room. Beyond the third chimney was a small block for the water tanks, the light entrance to the engine room and a reserved space with a promenade deck for engineers. To the side of this block was a skylight that covered the cupola that went over the first class rear staircase. The fourth chimney did not fulfill the function of expelling smoke from the boilers; For this reason, it was given the function of providing ventilation to the lower kitchens and the second engine room where the turbine that moved the central propeller was located. On either side of the fourth funnel was the raised ceiling of the first-class smoking room on the lower deck. At the end of the deck were the second class entrance and stairway (which descended to F deck). Likewise, the passengers had their respective promenade deck.

Deck A

Also known as the promenade deck, this level housed the cabins (forward), the reading room, the common lounge, the smoking room, the Verandah cafes (divided in half by the the second class staircase) and large enclosed spaces for walks on both sides of the first class ship. Its use was only for first class, since the second class staircase had no exit to this deck.

Originally it was planned to be built with the upper middle part open as in the case of the Olympic, but due to a change in the layout of the rooms on B deck during the last weeks of construction, it was decided to close the room with windows. forward promenade deck, so that half of the deck was closed up to where the reading room ended and the other half was left open, from the beginning of the common room to the end. At the front, near the first fireplace, were the first-class standard rooms; Decorated with white pine paneling, they featured electric stoves and luxurious mahogany furniture of the period. The interior rooms on this deck had the facility to receive lighting from the upper deck.

Behind the stairway and the entrance were the three elevators for the exclusive use of first class, which transported passengers up to E deck, the grand staircase to its first stop just before the second smokestack. Then came a passageway that was decorated in the same style as the first-class entrance and featured a revolving door. This corridor led to the reading room and the first-class common room. The reading room was a room decorated in the Georgian style with white wood paneling and floor-to-ceiling windows that stretched out onto the boat deck, giving it good lighting. It also had a decorative electric fireplace.

Port side first class ride on A deck of the Titanic, viewed from a point closer to the bow (left) and stern (right). To the side of the reading room and in the middle of the second and third fireplaces was the first class main salon, which was decorated in the Louis XV style, inspired by the Palace of Versailles. It was upholstered and had beautifully carved wood paneling on the walls. In the front part, near the door, there was an ornamental fireplace on which was a miniature of Diana of Versailles, better known as Artemis, and above all, a large mirror. On the night of the sinking, this lounge gathered first-class passengers before the order was given to begin the evacuation. The windows extended, as in the reading room, to the boat deck. One of its biggest attractions was its large chandelier, which was located in a small dome with carvings. The hall was subdivided into small private areas separated by mirrored walls and bronze sconces. Here books could be taken out thanks to a shelf located in front of the third fireplace. On both sides of it were a clock and a barometer. At the rear, on the port side, was a passageway with another revolving door, which connected the saloon to the rear stairway, much like the forward Grand Staircase, but slightly smaller and less detailed.

Towards the stern, there was access to the smoking room, a favorite place for first-class men after dinner. It was decorated in the Georgian style but paneled in dark mahogany. On the same panels there were bronze ornaments, which gave it a certain elegance. Its windows were not translucent but stained glass. In addition, it had some tinted glass embedded in the walls.

The floor was linoleum, with a pattern that was used in other areas of the ship. The first-class smoking lounge was higher than the deck height as its ceiling was raised a few inches higher on the boat deck. In this elevation, there were some small stained glass windows that had the shape of half an elongated ellipse. In the center of its rear wall, the room had a white marble fireplace that was the only one used in the entire ship for heating purposes, for this reason it had two baskets of coal, one on each side; Above this white piece was a painting titled "Plymouth Harbor". He had access to a bar that he shared with the cafeterias at the end of the deck. It communicated with the port side through a revolving door. The last first-class spaces on this level were the bar and the two Verandah Cafes. Its decoration was based on English country houses and its walls were covered with ivy and mirrors, which gave it a spacious effect. Natural lighting came from the four large iron windows that each cafeteria had, which added to the open deck, allowed diners to have a magnificent view of the ocean. Snacks and light meals were served here, but not lunch. The starboard cafeteria was converted into an unofficial playroom for the first class children during the voyage. The second-class staircase passed this level, as it had no exit.

Deck B

Also called the bridge deck, this floor was designed primarily to accommodate first-class passengers and to have a promenade deck that would extend from its front to rear, divided just after the rear stairway first class to make way for the second class promenade deck. As on the upper deck, Ismay made observations on the Olympic's maiden voyage and found that this section of the B-deck promenade was not as popular as the one on the upper level.

It was thus that it was decided to completely transform the B deck, adding more cabins in the front part and making some modifications in the middle and rear parts. Private promenade decks were added to the Parlor Suites, (deluxe cabins, which were located one on each side just past the front steps). The other suites were transformed, being extended towards the hull of the ship and changing the location of their private bathrooms.

The first class Á la Carte restaurant was remodeled: the dispensations would no longer be near the entrance by the stairs, that space would be only for entrance; The space was expanded to the port side and to the starboard, the popular Café Parisien was created, which turned out to be a complete success. The restaurant had space for 137 patrons. The deck windows were similar to those on the upper level enclosed promenade deck; but, when the changes were made, these were transformed into narrow windows and only the original windows were preserved in the first class boarding, private decks and starboard cafe.

This was the first deck to run the full length of the ship, even though it was divided into three parts, the fo'c'sle, mid-ship, and poop deck. In the forecastle was the mast for the lookouts and the first hatch, which (unlike the others) functioned as a skylight, due to the small portholes on its deck. The system that moved the two forward anchors exposed the heavy chains in this space; likewise, the crane that was located behind the anchor served to transport it. This area was exclusively reserved for the crew, so third-class passengers could not access it from the lower level, even with stairs. Instead, at the other end, the fantail functioned as a promenade deck for third class.

The middle part of this deck was the longest. At the front were the standard first-class cabins, which extended to the Grand Staircase. On both sides of it were the first-class boarding entrances; unfortunately, no photographs of these sections exist on the Titanic.

To the stern was the second-class smoking lounge along with a private promenade for the same class on either side. The smoking room was embellished in the Louis XVI style, paneled in oak and floored with linoleum tiles. The tables were surrounded by oak armchairs upholstered in green leather. There was an adjoining bar so the bartenders could supply drinks and cigars; as well as an adjoining toilet.

In front of the first-class entrance were the Parlor Suites, the most expensive suite on the ship. Each consisted of a sitting room, two bedrooms, two dressing rooms, a bathroom, and (what was added in the conversion) a private promenade deck. There was one set on port and one on starboard. The two promenade decks were decorated in the Tudor style.

Deck C

This deck, similarly designated the Refuge Deck, was primarily dedicated to first-class passenger accommodations and crew spaces (both of which were confined to the bow). This deck had four cargo hatches, two in the bow and two in the stern. The first class aft staircase ended on this floor. Aft, there was the first class general lounge, to starboard, as well as the smoking room, to port, with the stairs also to third class.

Between the center and the stern were the second-class general room or library, on the sides of which there were two interior walk areas for second-class passengers. This room was decorated in the Adam style. Mahogany chairs and tables furnished the room, offering desks with lamps by the windows, plus a large bookcase that served as a lending library. This room combined the functions of library, living room and writing room.

In the forward part, under the fo'c'sle, there were two cabins (one on each side of the ship) for the deck men. Also, there were two dining rooms for staff use; the first, with capacity for 35 people, belonged to the sailors and was located on the port side, after a cabin and before the crew's kitchen. To starboard was the dining room for the boiler stokers, with capacity for 87 people. On either side of the structure were stairs leading to the stokers' cabins on the lower deck. At the bow, there was also the anchor mechanism. Finally, next to the open space going down the fo'c'sle, was the crew's hospital. That open deck belonged to third class, so access stairs (one on each side) were installed from his enclosed space on D deck.

Deck D

Similarly referred to as the saloon deck, in the forward part of this deck were the engineers' quarters and a third-class common room. After being separated by a bulkhead, the first-class rooms followed, which were decorated with white wood paneling that extended to before the elevators. The men's bathroom was located forward with four shared bathtubs and the ladies' bathroom was located aft with another four shared bathtubs. In this section they had a small pantry. Then there were the first class boarding gates (two on each side), which closed hermetically by adhering to the hull; they were closed inward with ornate double bars. The only lighting in these departure lounges came from the two rectangular windows on each door and was decorated with white carved panels on a white linoleum floor; They also had a double door of the same design as those that connected to the dining room (wood with iron) and an arch that led to the elevators. To the stern, each room had a display case.

Descending the steps, passengers entered the reception room, decorated with rattan armchairs and tables and white wood paneling, this room was attached, through double doors, to the first class dining room.

The first-class dining room was in the Jacobean style, in a combination of white paneling and mahogany furniture, with lamps on all the tables and profuse stained glass windows, receiving natural light from a double row of portholes; towards the bow there was a space for the piano, this was the most spacious room on the ship, as it could accommodate 554 diners. First-class dishes included fillets of turbot, grilled lamb chops, salmon with mayonnaise, custard and apple meringue.

The second class dining room was located aft, with natural wood paneling and chairs of the same material, this dining room was almost as spacious as the first class one and the food served in it came from the same galley as the first class one. food from the dining room first. It could accommodate 394 people. Breakfast was served on the second-class menu: smoked herring, grilled ham, fried eggs, fried potatoes, tea and coffee; and for lunch: chicken curry, rice, lamb with mint sauce, fruit, cheese and cookies.

This deck also housed the ship's hospital, which had five private cabins, each with a stretcher and a very complete first-aid kit, according to survivors' accounts. The hospital could only be used by first and second class passengers. The second-class passenger gallery served as a meeting point for all second-class passengers after dinner.

To the stern were the second-class cabins, fully aft the third-class accommodation along with two bathrooms each containing a bathtub, the only two available to third-class. In the forward part was the place for the stokers and the stairs for the crew.

Deck E

This deck, also known as the upper deck, mainly housed the crew cabins with their corresponding dining room. At the stern were the second class accommodation with two stairs, one of them with an elevator, a barbershop, a shop, a room where the musicians kept their instruments and at the stern all the third class cabins next to a staircase. The first class Grand Staircase along with its three elevators ended on this deck, both giving access to the last first class cabins.

Towards the bow, the third-class and crew accommodations were located, with three small stairs and also some stairs for the exclusive use of the crew. A long corridor, more than 100 m long and known by the sailors as "Scotland Road", ran through a large part of the superstructure, communicating mainly the crew quarters, being transited both by the latter and by steerage passengers. In the middle, through the aforementioned corridor, there were stairs that led to the third class dining room. In addition, this floor housed a large number of public bathrooms for both passengers and crew.

Deck F

Third class aboard the Titanic was noticeably more comfortable than that offered by many of its competitors, although third class passengers were granted the smallest proportion of space on board and very few facilities. All passengers were accommodated in private cabins of no more than 10 people. There were 84 two-berth third-class cabins, and in total 1,100 third-class passengers could be accommodated.

This level, also called the middle deck, was occupied by the center of the third-class living-dining room, together with its kitchen and pantry, with stairs to access it from the upper floor. Said room was actually two rooms divided by a watertight bulkhead. Its walls were painted white enamel and decorated with posters of the White Star Line's parent company, the International Mercantile Marine Company (IMM). Its capacity was 473 diners. Despite the economic condition of the passengers, they were served breakfast, lunch, lunch and dinner, which included: Gruel, porridge, smoked herring, ham, eggs, boiled potatoes, rice soup, cold cuts, bread, tea, coffee, fruit, cheese and biscuits.

From the center to the stern were the quarters for the stewards, the second-class cabins with two stairs and an elevator, and the third-class quarters with a single stairway. From the center to the bow were rooms only for first class passengers such as the Turkish baths, the electric baths, the swimming pool (the third in the world to be installed on a ship) and the tribune for the spectators of the squash room. Forward all the way were the third-class cabins with stairs and a few stairs for the crew. The first-class front Grand Staircase definitively ended on this deck, which allowed access to the Turkish baths, the electric baths, the shampoo rooms and the swimming pool. The two second-class stairs also ended next to the elevator of one of them.

The exact location of the ship's kennel is unknown. On the Olympic, she was located on the upper deck. On the Titanic it is possible that she was also on the boats deck, although it is also speculated that she was located on F deck, near the third class galley.See Pets aboard the RMS Titanic.

Deck G

Also known as the lower deck, it was divided into two parts; the bow and the stern. Since in the middle were the holes that housed the large engines and boilers that rose from the engine room, two decks below.

Towards the stern, various pantries stored some food such as ice cream, fruit, vegetables, eggs, milk, bacon, butter or fish. Further aft, some cabins for crew, for third class and the last ones for second class that could be accessed by two stairs without a lift. In the bow, was the squash and fencing room, to access it you had to go down some stairs from Deck D, three decks above. Forward at all, the mail sorting room was located next to the first-class baggage hold and some third-class and crew cabins adjoining some stairs for the crew and others for third-class passengers.

Boiler deck

This deck and the lower deck were known as the "guts of the Titanic." This deck was divided into the bow and stern, as was the upper deck, Deck G. In the middle were the holes for the coal bunkers (containers that came from the lower deck and stored the coal) of the boilers and pistons rising from the engine room. At the bow was the cargo area for the second and third class, the first floor of the mail room and some stairs for the use of the crew. Aft, there were warehouses that kept drinks such as wine, champagne or mineral water and a refrigerated cargo area.

Machine cover

On this last deck, before the double bottom, the gears were located from stern to bow, together with the 16000 HP Parsons turbine, which drove the ship's central propeller, and the fresh water tanks. The central propeller rotated by another type of gear system. Then there were steam engines, with pistons four stories high; It was about two four-cylinder engines with a power of 30,000 CV that was obtained from the large turbine.

Next, the six boiler rooms. Each room contained five boilers except for the one closest to the bow, boiler room number six, with only four. Each boiler, weighing almost 100 tons, sent hundreds of liters of steam through tubes to the main engine room, where it moved the pistons. Between room and room, in their respective bulkheads, twelve watertight doors could be closed automatically from the command bridge, located nine decks above. At the bow, the last cabins for the stokers were located. On this floor there were iron stairs for access to the machines of the workers and stokers, in addition there were also the condensers and the electrical room.

Crew

Of the almost 900 people who were part of the Titanic crew, 66 belonged to the deck crew (officers, ratings, lookouts and boatswains), 325 were mechanics (coalmen, stokers, oilers, electricians, etc.), and finally 494 were members of the care team (purses, stewards, cooks, radio operators, etc.). The ship's commander was Captain Edward Smith, the most respected officer of the White Star Line and a extremely popular captain with first-class passengers, having commanded all of the company's newest and largest ships since 1904. Henry Wilde arrived at the last minute to be chief officer and second-in-command of the Titanic, causing a change in the officers' hierarchy. This made Titanic's three most highly-graded officers the same as those who had previously served on Olympic (with the third being First Mate William Murdoch, who was originally to be ace). appointed as chief officer). In addition to them, Second Mate Charles Lightoller, Third Mate Herbert Pitman, Fourth Mate Joseph Boxhall, Fifth Mate Harold Lowe, and Sixth Mate James Moody were also on board. They were in charge of commanding the deck crew and ensure the operation and proper functioning of the entire ship. They were helped by boatswains who were in charge of the rudder wheel, the lookouts who worked in the top, and the sailors who were in charge of maintaining the various devices on board.

The crew worked in the bowels of the ship. Under the command of Chief Engineer Joseph Bell, they were responsible for the engine room and for keeping the Titanic running. The 29 boilers were fed by three hundred stokers operating under terrible conditions. Very few members of the mechanical team survived the wreck.

Ultimately, the care team was far more diverse and did the most common work. Most were flight attendants accompanied by some receptionists, however it also included cooks, such as Hendrik Bolhuis. His duties were to take care of the ship's cabins and facilities, in addition to attending to the passengers. In the direction of all the attention crew members was the chief purser on board Hugh McElroy, also responsible for addressing any complaints that the passengers might have. The two radio operators, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, are also listed as part of that crew.

Guarantee group

From among the workers at the Harland and Wolff shipyard, the company selected a guarantee group comprised of outstanding workers in their respective trades to accompany Thomas Andrews on her maiden voyage. This select group had the mission of solving any minor inconvenience that required their good offices, for them it was a pride to belong to this group and in the shipyards they competed to be considered. These specialized workers occupied first and second class cabins and were considered just another passenger. The Titanic guarantee group consisted of nine people:

- William Henry Campbell - Carpenter Assistant

- Roderick Robert Crispin Chisholm - Drawing

- Alfred Fleming Cunningham - Adjuster

- Anthony Wood Frost - Adjuster

- Robert Knight - Adjuster

- Francis Parkes - Fontanero

- Henry William Marsh Parr - Electrician

- Ennis Hastings Watsons - Electrical Assistant

- John H. Hutchinson - Carpenter

First-class orchestra

The Titanic orchestra consisted of eight musicians. However, the band performed in two distinct groups; one was a quintet led by violinist Wallace Hartley, 33, and the other a musical trio that played for the patrons of the rrestaurant à la Carte. Each ensemble had its own melodic repertoire. Under normal circumstances, they did not perform tunes together, although Hartley exercised direct supervision over all the musicians. According to some accounts, the composition and number of the two musical ensembles may not have been entirely fixed, with some variation possible between the two ensembles. different performances that will sound during the journey.

The remaining members of the band were:

- Theodore Brailey, a pianist, 24 years old.

- Roger Bricoux, a chelist, 20 years old.

- John Clarke, 28-year-old bassist.

- John. Jock Hume, 21-year-old violinist.

- George Krins, 23-year-old violinist.

- Percy Taylor, a chelist, 32 years old.

- John Woodward, Chelist, 32 years old.

The musicians had not been directly hired by the White Star Line, but were actually employed by the company C. W. & Liverpool-based F.N. Black, the exclusive agency for the major shipping lines. On the other hand, the soloists were members of the Amalgamated Musicians Union. While traveling aboard the Titanic as workers for the Blacks, they stayed as second-class passengers. Therefore, they were not crew members.

The ensemble led by Hartley (who included violinist John "Jock" Hume and cellist John Woodward) played music daily in the first- and second-class areas of the liner. His working day in first class covered from 11:00 a.m. to noon, acting at the entrance to the boat deck and in the reception room on deck D, first entertaining between 4:00 p.m. and 5:00 p.m., at tea time, and finally from 20:00-21:15, after dinner. In second class, his chords were heard in the second class aft entrance hall of C deck in the morning from 10:00 to 11:00, in the afternoon from 17:00 to 18:00 and at night between 21:15-22:15.

Maid voyage and sinking

Preparations prior to departure day

The Titanic arrived at pier number 44 in the port of Southampton at dawn, shortly after 01:15 on Thursday, April 4, 1912, from Belfast. She docked with her port side facing the jetty.

Her arrival did not prompt any formal greeting or welcome ceremony, quite the opposite of her sister ship, the Olympic, when she entered the same dock for the first time in 1911. During that Thursday, the ship would look decked out with a large number of multicolored flags and banners.

The preparations were developed throughout the 6 days of stay in the port city: provisioning, accommodation of the recruited crew, habituation to their obligations, loading and unpacking the supplies on board, decoration work, wall painting, furnished, carpeted, etc. Because the ship had not yet been fully completed, she was not put on public display during her first stay in Southampton as was customary. As a result, she continued to work inside her on conditioning tasks and minor installations, although the ship would leave with some unfinished sections.

After the liner was moored, then second mate David Blair instructed lookout George Hogg to keep the set of binoculars he had borrowed in his cabin, in order to prevent them from getting lost while the ship was underway. the dock. To do this, Blair gave Hogg his keys to take the binoculars to his cabin and then return them to him. The task accomplished, on his way back to hand over the keys to the second mate, Hogg was called upon to do other duty, so he gave the keys to seaman William Weller to return to Blair.

However, a late replacement in the ranks of the senior officer corps meant that Second Mate Blair was dispensed with on the first voyage of the Titanic. In the days leading up to April 10, it was decided that Chief Officer Henry Wilde would take the position originally held by William Murdoch, demoting him to first officer. In the same way, the now former first officer Charles Lightoller would be relegated to second in his category, thus replacing Blair. On 9 April, David Blair abandoned ship accidentally taking the key to the observation turret storage locker, leaving the binoculars locked there or in his cabin. This error would contribute to a great deal of confusion in the attempt to locate him during the cruise.

On the eve of the day of departure, England had just suffered a fierce coal mining strike, which began on February 29 and ended on April 6 of that year, which directly affected the commercial dynamism of the shipping companies, in the same way as the rest of the economic sectors since said mineral was the predominant fuel for the operation of the industry, as well as for most means of transport at the time. Due to this situation, as coal production was reduced, the activity of many ocean liners came to a standstill, triggering thousands of unemployment.

With the critical situation derived from the strike, it was necessary to gather enough fuel so that the Titanic could undertake its maiden voyage. For that reason, the scheduled voyages of several White Star Line and IMM ships to transfer their coal reserves—including some of the Olympic's surplus supply—to the new liner, which had arrived from Belfast with about 1880 tons of fuel and to which about 4427 were added while it was in the berth. Having consumed 415 tons during her stay in the dock, at the time of setting sail, the famous steam housed some 5892 tons of fuel in her coal bunkers.

Among the ships parked on the approaches, the RMS Majestic and the RMS Oceanic stood out —both belonging to the same company as the Titanic— as well as the SS Philadelphia, St. Louis, and the SS New York. Some of the Titanic passengers had originally purchased travel tickets on one of those ships. However, when they were withdrawn from service due to the strike, they were transferred to the brand new ship.

On April 6, most of the shipboard staff were signed. About 250 crew members who had recently disembarked from the Olympic joined the staff of the new ocean liner.

On April 8, fresh food began to be shipped in the ship's cold rooms and pantries. As a guide, among some of the stored supplies there were; 75,000 lbs of meat, 11,000 lbs of fish, 2,500 lbs of sausages, 40 tons of potatoes, 250 barrels of flour, 40,000 eggs, 7,000 heads of lettuce, 36,000 oranges, 36,000 apples, 6,000 lbs of butter, 1,500 gallons of milk, 1,750 lb of ice cream, 2,200 lb of coffee, 800 lb of tea, 15,000 bottles of beer, 1,000 bottles of wine, 850 bottles of spirits and 1,200 bottles of mineral water.

On April 9, Maurice Clarke, the emigration officer of the Board of Trade, entered the ship with the task of verifying compliance with all the security regulations of the named entity and, if the verification was satisfactory, authorizing departure the next day. Everything related to the rescue equipment was examined and, among the tests carried out, the stability of the ship was tested.

Ultimately, Clarke completed most of her inspection that day and would return early the next morning to finish her checks.

First day of the journey, April 10

Wednesday, April 10, dawned fairly cloudy with a temperature of almost 9°C, although occasionally the sun peeked brightly through the clouds. Ship designer Thomas Andrews, 39, embarked at 6:00 and began to inspect the ship. At that time, many crew members began to gather on board. Captain Edward Smith, 62, boarded at about 7:30.

Crewmen began to gather for the formal meeting of Board of Trade Inspector Maurice Clarke and White Star Line Supervisor Benjamin Steele around 8:00. Due to the large size of the crew, they were assembled separately by like-minded groups—the stokers, stewards, and sailors—in different locations. One by one, each crew member had to assemble and line up in front of Captain Smith, the ship's officers and surgeons, surveyors Clarke and Steele, and the Board of Trade physician. Record sheets were drawn up, roll call was taken, people were counted and they underwent a medical examination to check that they were in good health. It took over an hour to complete the crew check.

After the aforementioned meeting, a mock lowering of the lifeboats was practiced and analyzed by Clarke and Steele. Chief Officer Henry Wilde, First Officer William Murdoch, Second Officer Charles Lightoller, Third Officer Herbert Pitman, Fifth Officer Harold Lowe and Sixth Officer James Moody assembled with the rest of the team around 9:00. Lowe and Moody were chosen to launch two boats - number 11 and number 13 - chosen for the tests, which would last half an hour and were partially canceled by the wind.

Early in the morning, passengers had begun to pour into the port of Southampton. Many of them arrived by means of two special trains -one for first class travelers and another for second and third class- that left from London Waterloo station, and which communicated directly with the facilities of pier number 44, where the Titanic was moored. The first-class train left London at 8:00 a.m. and reached Southampton at about 11:30 a.m. According to 36-year-old British second-class passenger Ellen Walfcroft, the second- and third-class train left Waterloo station at 8:30 a.m. and arrived at Southampton Pier at 10:15 a.m.

Third-class travelers would be checked for health, prior to entering the ship, to verify that they did not carry infections. Similarly, the passengers' luggage was sorted into two sets before being loaded on board; some met specific conditions to be deposited in the Titanic's holds, while others were authorized to be kept in the cabins of the travelers.

The south portico building coupled the port with access for first-class passengers, through the forward gates of the B deck of the Titanic. It was also possible to board this class via the doors on deck D of the ship. Jacques and May Futrelle were about to enter through one of those two entrances, and shortly after doing so, they ran into some acquaintances; the Harris marriage. The Futrelles were delighted to find out that Henry and Renee Harris would be staying in cabin C-83, which was located practically opposite their own. From then on, both couples would spend a lot of time together during the voyage.

Adolphe Saalfeld passed first class with his nephew as a visitor, the two of them wandering aboard for an hour. Saalfeld would praise his bedroom, the C-106: «I really like my cabin, it is like a living room with a bed and quite spacious. [...] My cabin is very nice, hot and cold water installed, an electric stove that you can turn on and off, a nice sofa with an oval table in front and, of course, everything is new."

British-Irish Henry Forbes Julian, a 50-year-old metalworker, was on a business trip to North America. He boarded first class shortly after 10:10, noting that few people were inside by then, and had his trunks unloaded in his E-60 cabin: "I just went over the ship and I've seen all the living rooms and stays. Everything is the most luxurious... The decks are magnificent, and the closed ones are set up more like smoking rooms. My stateroom is not the one shown... on the floor plan of the Olympic... However, it is more like a small bedroom than a ship's cabin [...]".

The gallery of the north portico of the pier was used for the entrance to second class, connecting with the rear hatches of deck C of the steamer. Through this entrance, the traveler Lawrence Beesley embarked at 10:00 accompanied by two friends who had come to see him off. The barriers separating the Titanic's first and second class spaces were open at the time, so Beesley and his friends explored various decks, dining rooms, and libraries. On the boat deck, they headed into the gym, where Beesley and his friend got on the two stationary bikes. At that time, the instructor of the sports facilities, Thomas W. McCawley, about 36 years old, arrived with a couple of photographers from a London newspaper. They photographed Beesley and his friend riding the bikes. Shortly after, more passengers entered, and the instructor explained to them the operation of the electric camel and horse, making two passengers climb on top of said devices, which were shaken by the action of a small motor, imitating the gallop of two animals.

After gaining access to second class, the Caldwells watched the crew loading the packages on board. Sylvia Caldwell, asked one of them: "Is this ship really unsinkable?" The waiter replied: «Yes, ma'am. Not even God could sink it."

Unlike many other travelers, Imanita Shelley, 24, of Deer Lodge, Montana, and her mother Lucinda "Lutie" Parrish, 59, of Woodford County, Kentucky, were terribly disappointed when they walked into his second-class cabin. Returning to America after a stint in England for Shelley to convalesce from a serious ailment, mother and daughter were outraged because they believed they had paid for the best accommodation available in their class, but were instead escorted to a very small cabin and located on one of the lower decks. Consecutively, Imanita and Lutie sent the chambermaid in search of the chief purser demanding a transfer to a better room commensurate with the cost of the ticket purchased, obtaining in response the impossibility of such a claim until the ship had left Queenstown, at which time the one that would review all the tickets and could detect any errors.

Third class would board Elizabeth Dowdell, a 31-year-old housekeeper from New Jersey, crossing one of the platforms that linked to one of the two openings on Titanic's E deck. She had a six-year-old girl, Virginia Emanuel, in charge of her. Young Virginia was the daughter of opera singer Estelle Emanuel, who had recently signed a six-month contract in England and had left her daughter in Dowdell's care. The little girl, accompanied by her nanny, was being sent back to New York, where her grandparents would take care of her. That morning was a bit stressful for Dowdell, because they were late in taking the specific railway that would take them to the port where the Titanic was docked, going up to it in a hurry. Once aboard the liner, they discovered they would be sharing a cabin with 24-year-old British servant Amy Stanley, who was headed to Connecticut to work as a babysitter.

Swede August Wennerström, 27, a typographer and socialist from Malmö, was another of the travelers who entered the most economical class. He had previously been prosecuted for insulting King Oscar II of Sweden. After his acquittal, he decided to go to the United States. He undertook the journey to Southampton along with two compatriots who would also agree as third class passengers; Carl Olof Jansson, also a 21-year-old socialist and carpenter from Örebo bound for Nebraska, and Gunnar Isidor Tenglin, 25-years-old and from Stockholm, but who had already lived in Burlington, Iowa between 1903 and 1908 and where he wished to reestablish himself. Inside the boat, Tenglin and Wennerström settled in the same cabin.

At 11:45 a.m., the bells rang and shouts of "Everyone ashore!" across the Titanic. So the visitors who had come aboard bade farewell to their acquaintances and descended the gangways. Shortly after, at 11:50, the sailor William Lucas, 25, would embark. Although he would not be the last to do so, since a few minutes later the leading stoker Arthur Pugh, 31, and his brother the 20-year-old butler Alfred Pugh. Another straggling group of six tinkers rushed inside the Titanic, but only 24-year-old John Podesta and 30-year-old William Nutbean made it in time to be cleared inside. on board.

Second-class passenger Lawrence Beesley watched — peering from the upper decks — the moment of some tension that led to the rejection of admission of some of those late workers, through the gangway that was ready to be removed from the lock aft of deck E:

[...] Just before the last walkway was withdrawn, a group of fire extinguishers ran through the dock, with their equipment hanging on their shoulders in packages, and headed to the walkway with the obvious intention of joining the boat. But a non-official [James Moody] who guarded the end of the shore of the walkway strongly refused to allow them to come on board; they argued, gesticulated, apparently trying to explain the reasons why they were late, but he [subofficial] remained stubborn and made them a gesture with a determined hand; the walkway was dragged back in the midst of his protests, remaining in the midst of his determined effort..]

The Titanic began her maiden voyage to New York on Wednesday, April 10, 1912, setting sail at about 12:15 p.m. of the ship The officers had gone to their vantage points to start the ship's departure; Chief Officer Wilde, 39, was on the fo'c'sle, supervising the crew manning the moorings. Close to Wilde and under his orders, 38-year-old Second Officer Lightoller worked. First Officer Murdoch, 39, was positioned on the sterncastle taking care of the mooring ropes there. He was assisted by the third officer Pitman, 34 years old, up on the rear docking bridge and next to his corresponding telephone and telegraphs. Fourth Officer Boxhall, 28, remained on the bridge carrying out orders by telegraph and filling out the logbook. Fifth Officer Lowe, 29, listening to the phones in the wheelhouse. Sixth Officer Moody, 24, was stationed on the last gangway linking the Titanic to the mainland, aft on E Deck.

A flotilla of six tugs, named Albert Edward, Hercules, Vulcan, Ajax, Hector, and Neptune, approached the liner to help her pull away from the pier and guide her into the main channel. With the access gangways already removed, although the two rear hatches of deck E were still open, the order to set sail was sent from the bridge. The men on the dock unhooked the mooring lines from the bollards which would then be rolled on board by the crew at the fore and aft ends. The barges slowly steered the Titanic into the Test River. Voyager 2nd Class Lawrence Beesley would observe:

[...] The Titanic slowly advanced through the dock, with the accompaniment of the latest messages and shouting farewells of those on the dock. There were no victors or whistles of the fleet of ships that bordered the dock, as could probably be expected on the occasion of the largest ship in the world that was made to the sea on its inaugural journey; the whole scene was quiet and quite ordinary, with little of the picturesque and ceremonial interest that the imagination paints as usual in these circumstances.

33-year-old Turkish baths waitress Annie Caton would recall the ship's orchestra playing light music on deck while passengers leaning on the railings waved farewells to the crowds at the berth. Chambermaid First Class, 24-year-old Violet Jessop would write in her memoirs of the departure of the Titanic:

Little by little, the Titanic got off the side of the drain and left on a soft April day. Sliding with grace, full of great hopes, upon the noise of farewells, waving flags and scarves. We were proudly escorted by the tugboats, resonating their farewells and [messages] of good luck, while from the dock the sounds weakened. Few staff members had time or opportunity to witness our departure.[...]

Incident with the SS New York

As the Titanic inched forward to join the River Test, it approached to pass parallel to the level of berths numbers 38-44. The RMS Oceanic was lashed directly at the 38th and alongside her was the SS New York double-lined. Meanwhile, on deck, Colonel Archibald Gracie was engaged in conversation with businessman Isidor Straus, who briefed him, pointing to the New York, that he had traveled on said ship in 1888, noting the extraordinary naval progress that had occurred since then.

By that time, some of the boats that attended the Titanic had moved away from it, as was the case with the Vulcan. On the bridge, Pilot Bowyer sent the command "slow forward" to the engine room. So the steam from the ship's engines began to induce the rotation of the two outer propellers. However, the action of the latter developed a powerful and complex series of suction forces under the confined and deep waters on the north side of the channel. The resulting waves caused the ropes that retained the New York to break, causing the Titanic to absorb it towards it when the latter moved alongside it.

James A. Paintin, 29, Commander Smith's butler, linked the risky event to what happened with the Olympic:

[...] the bad luck of the Olympic seems to have persecuted us, for as we left this morning of the dock we spent quite close to the "Oceanic" and the "New York" that were tied in the old "Adriatic" mooring, and whether it was suction or what it was, I don't know, but the strings of the "New York" broke like a piece of cotton and [that boat] slipped towards us. There was a great expectation for some time, but I don't think there was any damage unless one or two people were knocked down by the ropes.

Arthur G. Peuchen, a first-class passenger from Toronto, Canada, was a 52-year-old chemical manufacturer who made regular transatlantic voyages due to the international scope of his business. He lived in room C-104. Peuchen would testify:

[I landed] Twenty minutes before I sailed, I'd say, half an hour.That was a good day. Shortly after leaving our dock, our wake or suction caused some trouble at the head of the dock we rode, where there were two or three ships from the same company as our ship. There was a great upheaval in those ships due to the breakage of their moorings, but there was no shock in ours, the Titanic. There was also excitement at the docks when the largest ship [probably the Oceanic] began to break one or two of its moorings. But I don't think there would have been any accidents. The smaller boat, I think it was the New York, got away, without its engines on and without self-control. The result was that nothing could be done. At first, it deviated towards our stern, and then it was carried [to the drift] getting very close to our bow.

I think we stopped our boat and we just stood still. They got one or two tugs to control the New York and took him out of danger. I think this problem probably delayed us three quarters of an hour. Then we left the port.

Jacques and May Futrelle watched the threat of collision against the SS New York unfold from one of the first-class decks, May would detail:

Because this was the inaugural trip of the Titanic, our departure was a great occasion. The docks and roofs of the Olympic [sic - Oceanic] and the New York, which were in the port, were crowded with people who had come to fire us. They cheered and greeted when we sailed: our orchestra played [...]. Jacques and I stopped by the nearest railroad to New York as we advanced.Suddenly we saw the New York shaking and moving: then his closest cable to us broke down and the muñón fell back on the deck, knocking down some people. I saw him start swinging towards us. Jacques shouted: Hold tight for the shock! I clung to the rail. The New York approached even more, and it seemed sure that we would crash; but just as his railing was about to touch ours, he changed direction beyond our bow.

I was a little scared. Jacques laughed and said: Well, you have to get out of your system anyway! It seemed that no one on board had superstitious thoughts about the small incident. If we talked about it, we just joke about it. We never know when our luck comes. It would have been much better if the New York had sunk us in the same port.

Lawrence Beesley was another witness to that event:

As the Titanic progressed majestically through the dock, the crowd of friends followed our passage along the drain, we came together to the steam level New York tied to the side of the dock along with the Oceanic, the crowd greeting those on board with the best they could for most of the two boats. But when the bow of our ship came to the height of the New York, a series of bursts were heard, such as those of a revolver, and on the side of the New York pier, coarse-string spirals plunged into the air and fell back among the crowd, who were alarmed to escape the flying ends. We expected no one to get hit by the ropes, but a sailor next to me was sure he saw a woman taking to get medical care. And then, for our astonishment, the New York approached us, slowly and stealthily, as attracted by an invisible force that could not resist. [...]In the New York there were shouts of orders, people running from one side to another, dropping strings and placing mattresses on the side where it seemed likely to crash; the tugboat that had been released a few moments before the Titanic bow, surrounded our stern and passed next to the New York pier, seemed to cling to this and started dragging it back with all the power of the engines that were not capable; [...]

At first, all appearances indicated that the sterns of the two ships would collision; but from the pop bridge of the Titanic, an officer who led the operations stopped us dry, ceased the suction and the New York, with his tug behind, moved obliquely through the dock, with his stern sliding down the side of our ship a few meters away. [...] But the whole expectation had not yet ended: the New York turned its bow inward, toward the dock, its stern swayed right outside and passed in front of our bow, and slowly advanced forward to the Teutonic [sic - possibly the Oceanic], which was tied to its side; [...] another tugboat approached and took over the New York by the prow; and between the two they dragged it, [...]

[...] A young American film photographer [William H. Harbeck] who had followed the whole scene with his wife, with anxious eyes, spinning the crank of his camera with the most evident pleasure while recording the unexpected incident in his films. Obviously, for him it was a great gain to have been aboard at that time, but neither the film nor those who exposed it came to the other side [of the ocean], and the filming of the accident [...] has never been projected on screen.

From the command bridge, the command to halt the ship's march was telegraphed. However, the stern of the SS New York continued to drift, approaching dangerously—in an arc—for the Titanic's rear port area. One of the two officers stationed in the stern called, through a megaphone, to the leader of the Vulcan tug, urging him to come to the rear port side of the great ship. Meanwhile, the Titanic's left side thruster reversed her motion to reverse. As the small dinghy fearfully moved to the indicated spot, it took a rope from the New York that immediately snapped under the strain. But she quickly clung to a second line with which the Vulcan, propelled to her maximum power, prepared to tow the out-of-control New York, in order to slow it down to prevent it from colliding with the Titanic.

| ||||

| Fases of the near meeting of the Titanic with the New York. |

The agitation of the water caused by the reverse rotation of the port propeller, added to the drag maneuver of the Vulcan, managed to stop the smaller of the two steamers when the separation between the two hulls had narrowed to just over 1 meter. Simultaneously, the Titanic began to move back through the channel, while the tugboats tried to avoid another threat of boarding caused by the wake of the brand new ship. The stern of the New York slid along the Titanic's port side, overtaking the latter's bow, and two tractor boats brought the straggling little ship to be temporarily tethered at the southern end of the pier jetty. At the same time, the RMS Oceanic was lashed with more cables, in order to prevent her from being pulled into the huge vessel as it resumed its course.

Once the situation was under control, the Titanic continued down the river. This mishap was seen by some on board as a bad omen, as referred to by 27-year-old first-class passenger Norman C. Chambers or second-class passenger Thomas Brown. On the other hand, second-class traveler Charlotte Collyer would affirm that no one was scared and that the boat had demonstrated its power. Before definitively leaving the port, the Titanic paused so that the reserve crew, who had not previously disembarked, could do so by means of the Vulcan. To do this, the tugboat was located in the port lock of the E deck of the great ship. This task completed, the Titanic resumed sailing for the second time with a delay of approximately one hour.

Journey across the English Channel

Setting course for Cherbourg, its first stop, the ship steered in the direction of Southampton Water, leaving the mouth of the River Test and skirting the Isle of Wight to starboard, to enter the Strait of Solent, through which it would channel towards the English channel. Already at sea, the Titanic would develop a speed close to 20.2 knots.

Immediately after the ship left Southampton, Chief Engineer Joseph Bell, 51, tasked Chief Stoker Frederick Barrett, 29, with the task of extinguishing a fire in the starboard tender at the forward end from boiler room number five, the result of spontaneous combustion resulting from the heat of the stove. It was rumored to have sprung up in Belfast, and the adjacent bulkhead was due to be examined after the fire had been extinguished. Pursuing this purpose, as much coal as possible would be extracted from the affected storeroom to locate the source of ignition and it was irrigated with a hose that was introduced under the control of Barrett and some 8 or 10 men. However, that work would last 3 days.

It soon became clear that the lookouts did not have any pair of binoculars. Accordingly, 24-year-old lookout George Symons went to the bridge to see if they could provide them; Second Mate Lightoller made some inquiries, however, he found none reserved for the top watchmen.

Lawrence Beesley would reminisce about the final departure from the port until the arrival of the first scheduled stop:

As we shipped down the river, the scene we had just witnessed [the attempt to crash with the New York ship] was the theme of each conversation: the comparison with the Olympic-Hawke collision was made in every small group of passengers, and there seemed to be a general agreement that this would confirm the theory of suction [...].We went down to Spithead, crossed the shores of the Isle of Wight that looked magnificently beautiful under the new spring foliage, exchanged greetings with a White Star tugboat that waited for one of its transatlantics to head in, and we saw in the distance several warships with accompanying black destroyers guarding the entrance from the sea. With a time of the quietest, we reached Cherbourg just when it was dark and left again around 2030 hours, after boarding passengers and mails.

First class passenger Ida Straus wrote the following letter to a friend after leaving Southampton:

Dear Mrs. Burbidge,You can't imagine how pleased I felt to find your exquisite basket of flowers in our living room [C-55] in the steam room. Roses and carnations are as beautiful in color and as fresh as if they were cut. Thank you so much for your sweet attention that we both appreciate.

But what boat [the Titanic]! So huge and magnificently decorated. Our rooms are furnished with the best taste and luxury, and are real rooms, not cabins. But the size seems to bring your problems: Mr. Straus, who was on deck when we sailed, said that for a moment, painfully little to repeat the Olympic experience in his first [sic - sixth] trip out of the port, but the danger was avoided soon and now we are well on our way through the channel to Cherbourg.

Once again, I thank you and Mr. Burbidge for your lovely attention and good wishes and for the pleasant satisfaction of seeing you with us next summer, I cordially greet you with whom Mr. Straus joins with every heart.

Very carefully,

Ida R. Straus

At 1:00 p.m., lunch was served for the passage. First-class perfumer Adolphe Saalfeld tasted his first maritime delicacy with much appetite: “I had quite an appetite for lunch—soup, fillet of plaice, a tenderloin steak with cauliflower and fries, Manhattan apple and Roquefort washed down with a large beer. frozen spaten, [...]».

In second class, it had taken Kate Buss quite a while to exchange her ticket for a dining ticket. She took a seat at a table where, among other diners, two clergymen were eating, Marion Wright, a 26-year-old Englishwoman, and Ernest Moraweck, a 54-year-old American doctor, whom she described as "very nice." Later he would apply her medical knowledge to her by removing some soot that had fallen into her eye. Later, Buss met Wright on deck:

[...] While he was there, said young man [Marion Wright] offered to share his travel blanket. I accepted. We asked each other questions. She's going to Oregon, but her fiancé's waiting for her to marry her in New York. [...]

Francis Browne, a 32-year-old Irish first-class passenger and Catholic seminarian, after documenting the ship's difficult departure with his camera, ate quickly in the dining room, wanting to be on deck when they crossed near the wight coast.

While he was taking his snapshots at the time they were circumambulating the waters of the Solent Strait, an American traveler interrupted him to ask him, surprised, why one coastline is so close to another. Browne would patiently, and even humorously, answer his insistent geographical questions about where they were passing through, but he noted that the hesitant American became more and more disoriented with each answer. Until at last Browne understood the source of the man's confusion, who mistakenly assumed that the shore of Wight, visible to the south from the ship, was the French coast.

Consecutively, the priest clarified: «Ah, that's not France, it's the Isle of Wight», to which the American replied, before leaving: «I see. I thought it was France." Browne would soon see the man on deck again and this time photographed him in front of the outer wall of the gym.

Priest Second Class Thomas Byles would observe during the itinerary across the English Channel:

[...] At lunch. We were still in Southampton Water, but when we left lunch we met between Portsmouth and Wight Island. [...] The wick channel was resolutely cluttered in sight, but we didn't feel it any harder than when we were in Southampton Water. I don't like the palpitation of the propellers very much, but that's the only move we get. I have discovered two other priests among second-class passengers: one Bavarian Benedictine [Joseph Peruschitz] and the other secular of Lithuania [Juozas Montvila]. [...]

Musical instrument dealer Henry P. Hodges, from Southampton and in his 50s, who was on his way to Boston to see relatives, would comment on his first sight in second class:

We've been doing great so far. You don't notice anything about the movement of this boat, but time is very good. On the top deck there are about 20 boys, from 20 on, spinning and singing. Others play dominoes and cards in the halls. Some read, others write. [...]

At tea time, around mid-afternoon, the musicians performed at the first-class reception. Among those who were having a snack in that room, was Elmer Taylor talking with his friend Fletcher Lambert-Williams, 43 years old. The Taylors had met Edward and Catherine Crosby and their daughter Harriette that morning—on the London-Southampton rail journey—and had hit it off ever since.

Because Lambert-Williams was traveling alone, Mr. Taylor offered to introduce him to the Crosby family, who were seated near them, although he was particularly keen that he should meet Harriette that way. Upon Taylor's introduction, the Crosbys suggested that they join their table for tea, to which Elmer and Fletcher agreed. The conversation that ensued between them must have been quite friendly, since later they would ask the flight attendant to grant them a table with capacity for 6 people in the dining room, and thus, they could continue their social interaction during the cruise.

That evening, Adolphe Saalfeld took a long walk and slept for an hour until 5:00 p.m. Later, at the Verandah Cafe, he savored a bread and butter coffee that he thought he should pay for, though he discovered it was free.

Henry F. Julian explored the nave, except for the Turkish baths and swimming pool: "The Parisian cafe is quite new and looks very real. [...] I also visited the gymnasium, which is full of the most marvelous machines, which cure all the pains of which the flesh is heir. There are more than three hundred first class passengers on board – a large proportion of Americans. The weather has been good, but cool and more or less cloudy."

First stopover in Cherbourg

After crossing the English Channel, the Titanic made its first stop in Cherbourg, France to pick up more passengers. The liner came in late, around 18:30 on April 10, as a result of the mishap in Southampton with the SS New York as she was leaving port, and anchored inside the breakwater, her starboard side facing the port city. The sea train, which came from Paris, arrived in Cherbourg around 4:00 p.m., bringing with it a part of the passage that would board the steamer through the French pier.

The ferry SS Nomadic was ready to depart at 5:30 p.m. with 142 first-class passengers and 30 second-class passengers who had purchased tickets on the Titanic, although the Titanic was not yet on the horizon. The 102 third-class travelers would be transported by the SS Traffic ferry. The latter approached first next to one of the sides of the Titanic, so the steerage passengers accessed the ship, in addition to being deposited the mail destined for Ireland or the US. Notable personalities would board in Cherbourg and stay in first class.

As the travelers awaited the arrival of the flaming steamer inside the Nomadic, Margaret Brown struck up a conversation with her friend Emma Bucknell, a wealthy 58-year-old widow whose late husband had founded Bucknell University in Philadelphia. After visiting her daughter in Italy, she was on her way to Atlanta, Georgia, where another of her children lived. She was accompanied by her employee Albina Bassani and she would occupy cabin D-15. Bucknell told Margaret that she had bad omens about boarding the new liner. Mrs. Brown just smiled, reassuring her. Similar bad feelings would later be recounted by some surviving passengers, such as Lucy Duff Gordon or Edith Rosenbaum.

Engelhart Østby, 64, and his daughter, Helen, 22, resided in Providence, Rhode Island. Østby was a widowed jeweler from Norway. Since 1906, he had taken Helen with him on his regular business trips to the Old World. On this occasion, father and daughter had vacationed in Egypt and southern Europe. While in Nice, they determined to return home by obtaining first-class reservations for the Titanic; Engelhart would occupy the B-30 cabin and the young woman the B-36. Helen would allude to:

We went to Paris and there we met two acquaintances, Mr. and Mrs. Frank Warren from Portland, Oregon, whom we had met in Egypt and who also had reservations for the Titanic. On April 10 we took the boat train to Cherbourg. The Titanic stayed in the port, illuminated and beautiful at night.

At about 7:00 PM, just after sunset, the Nomadic pulled up along the side of the Titanic to transfer first and second class travelers to the great ship. They would enter through a walkway that connected with the entrance to the D deck of the Titanic. In this Gallic port, 274 people were added to the passage —142 first class travelers, 30 second class and 102 steerage—. About fifteen first-class passengers—among them the parents of the Countess of Rothes—plus about nine second-class passengers got off the ship in Cherbourg. In addition, many items of mail, cargo, and baggage were unloaded for the tenders.

Margaret Brown, would be one of the travelers who had to cross the aforementioned gangway to enter the Titanic and then went to her cabin, the E-23:

A boat train (luxury train) from Paris reached Cherbourg at 17:00 on April 10. When we got here, no boat was seen in sight. The Titanic was late, as he had had some difficulties in leaving the Liverpool docks [sic - Southampton]. We all approached the [SS Nomadic] ferry that was waiting to move hundreds of passengers to the largest of the sea palaces [the Titanic], which then turned out to be the tomb of many of them.After an hour or more delay, in the cold gray atmosphere, the Titanic chimneys, the world's largest masterpiece of modern transatlantic, appeared on the other side of the breakwater.

In a few more minutes, this marvellous floating palace [the Titanic] appeared at sight around the dike curve and lowered the anchor. The shuttle [Nomadic] lit his engines, and after half an hour in a moving sea we were next to the Titanic keel. The movement of the small boat [Nomadic] in the rough sea made most passengers feel uncomfortable and weak. They were all frozen.

On boarding the ship [the Titanic], a large number of passengers immediately went to their cabins. The trumpet [which he warned] for dinner was half an hour later, but he failed to summon many to his magnificent dining room. The electric stove and the hot blanket [which offered the cabins] were too comfortable to be abandoned even for a dinner of many dishes, even in the desire of the inner man.[...]

Edith Rosenbaum recounted the relatively dangerous entry process onto the Titanic, from the Nomadic:

[...] The train journey from Paris to Cherbourg was quite pleasant. [...]But when I arrived in Cherbourg I felt a very nasty premonition of problems that would come later. In fact, I was so strong [premonition] that I telegraphed my secretary in Paris, expressing my fears.[...]

We sat on the huge [SS Nomadic] shuttle, which had been built especially the previous year for these new White Star ships, and for three hours we were tiring and waiting. It was cold, it had been raining. I remember sitting next to Colonel John Jacob Astor and his wife, who were on their wedding trip, playing with their big dog [Kitty]. The colonel told me that the construction of the Titanic had cost ten million dollars and emphasized that it was insubmersible, a miracle of modern naval construction.

Finally a murmur traveled the auxiliary boat: The Titanic is in sight!.