RMS Lusitania

The RMS Lusitania was a British ocean liner designed by Leonard Peskett and built at the John Brown & Company in Clydebank (Scotland) for the illustrious Cunard Line shipping company. It was named after the ancient Roman province of Lusitania, and joined the Cunard fleet in August 1907. It was at the time the largest passenger ship in the world along with its sister ship, the RMS Mauretania, until the Rival company White Star Line launched the RMS Olympic in 1910, and the RMS Titanic in 1911.

The Lusitania was built as part of Cunard's competition with other foreign shipping companies, mainly German, for supremacy in the passenger transport trade on the Atlantic route. The company with the fastest and most luxurious ships would have a commercial advantage: the Lusitania and her sister ship, the Mauretania, provided a regular service between the British Isles and North America until the outbreak of the First World War.

The Cunard board of directors decided to use Parsons steam turbines as a propulsion method for both ships, which allowed both to win the coveted Blue Band, the award for the fastest ship to cross the Atlantic, at different times in their careers; as well as to maintain the speed record for two decades. In addition to being the fastest, both ships had innovative facilities for their time, providing 50% more space for each passenger, in contrast to their rivals. Europeans, which allowed them to offer unprecedented luxury.

The Lusitania and her sister ship were designed to become armed auxiliary cruisers in times of war. However, due to their high fuel consumption, they proved unviable for this task, being released from it shortly after the outbreak of World War I. Due to these events, the Lusitania rejoined line service in the North Atlantic, while the Mauretania was assigned as a reserve ship, until the situation that occurred in the Battle of Gallipoli required its services, being used as a troop transport. and hospital ship.

On May 7, 1915, in the middle of the submarine war between the German Empire and the United Kingdom, the Lusitania was identified and torpedoed by the German U-Boat SM U-20, sinking in just eighteen minutes. The ship disappeared about 18 km off the Old Head of Kinsale cape, in Ireland, taking with it the lives of 1,198 people out of the 1,959 on board.

The tragedy shocked the world and turned public opinion against Germany, contributing to the entry of the United States into the war and becoming for the allies of the Triple Entente an iconic symbol of recruitment and why was fighting.

The Lusitania had the bad luck to fall victim to torpedoes when the war was in its early stages and techniques for evading submarines had not yet been perfected. The two sides of the conflict argued over whether the liner was a legitimate military objective, since in addition to passengers it was carrying numerous ammunition and other war supplies. Likewise, several attempts have been made to find out exactly how it sank, and the discussion This continues today.

Development and construction

Background

The Lusitania was built as part of the Cunard Line's competition with other shipping companies, mainly German, for passenger transit in the Atlantic Ocean. In 1897, the German ship SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse became the largest and most luxurious ship in the world and, the following year, she took the Blue Band from Cunard's RMS Campania and RMS Lucania.

Thus, Germany came to dominate passenger trade in the North Atlantic: in 1906, it had five four-funnel liners in service, four of them owned by the Norddeutscher Lloyd company, being known as the Kaiser class ships.. At the same time, the International Mercantile Marine Co., owned by the American financier J. P. Morgan, tried to monopolize the passenger trade by acquiring several shipping companies, including the British White Star Line. At the beginning of the century, this company He had gained great popularity with his new ships, the RMS Celtic, RMS Cedric, RMS Baltic and RMS Adriatic.

In view of these events, Cunard was determined to regain its prestige. Through an agreement signed with the British government in June 1903, the company received a loan of £2,600,000, repayable over a period of twenty years, to finance the construction of two new liners, the Lusitania and the Mauretania.

Both ships were designed by naval architect Leonard Peskett. With a cruising speed close to 24 knots (44.4 km/h), each vessel would receive an annual operating subsidy of 75,000 pounds, along with a mail contract worth £68,000. In exchange, the government agreed to finance the construction of both ships, under the condition that they would be built to Admiralty specifications so that they could be converted into armed cruisers if necessary.

Construction

The construction of the Lusitania was carried out in the Scottish shipyard of John Brown & Company, in Clydebank. Construction work began on August 17, 1904, with the laying of the keel. Lord Inverclyde, the president of the Cunard Line at that time, was in charge of formally inaugurating the construction by hammering the first rivet of the keel.

Cunard nicknamed the ship 'the Scotsman', in honor of the country where it was built and to differentiate it from its sister ship, the Mauretania, whose construction was carried out in parallel at the Swan Hunter shipyard, in England.

The final details for the designs of both ships were left to the designers of both shipyards, so that both the Lusitania and the Mauretania differed in numerous aspects, such as the design of their hull or the design of the vents. the boat deck (which followed a more traditional design on board the Mauretania, in contrast to the cylindrical design featured on the Lusitania). Furthermore, the Mauretania was designed with a forecastle slightly larger than that of the Lusitania, exceeding her length by almost a meter. In addition to this detail, the Mauretania was designed to displace a greater tonnage, as well as a higher power for its turbines.

The gantry of John Brown's shipyard had to be reconfigured to allow the Lusitania's 800-foot hull to be launched across the widest available part of the River Clyde, where it crossed a tributary. The new slipway occupied the space of the previous two and was built on reinforcing piles driven deep into the ground to ensure that she could temporarily support the concentrated weight of the large ship as she slid into the water. The company had to invest £8,000 to dredge the Clyde, £6,500 to install a new gas plant, £6,500 in a new power plant, £18,000 in the extension of the dock and 19,000 pounds for the acquisition of a new crane capable of lifting 150 tons, as well as £20,000 in additional machinery and equipment.

The Lusitania was launched into the sea on June 7, 1906, eight weeks later than planned due to labor strikes, and eight months after the death of Lord Inverclyde. The Royal Princess Louise was invited to the launching ceremony to christen the ship, but she was unable to attend, so the honor fell to Inverclyde's widow, Lady Mary. Six hundred guests and thousands of spectators attended the ceremony. To slow the progress of the Lusitania once it entered the water, thousands of tons of drag chains attached to the hull by temporary rings were used. Weeks before launching, the ship's four propellers were installed; however, on later ships, these would be placed in dry dock to prevent them from being damaged when colliding with another object during sliding. After launching, the Lusitania was towed to the dry dock, where final construction and fitting out work would take place over the following year.

The sea trials were carried out in July 1907, with a preliminary cruise organized on the 27th with representatives of the Cunard Line, the Admiralty, the Chamber of Commerce and the John Brown shipyard on board the ship. During testing, the Lusitania reached speeds of 25.6 knots (47.4 km/h) over a measured mile (1.6 km) at Skelmorlie, with its turbines running at 194 rpm producing 76,000 HP power. The ship traveled four times between Corsewall Lighthouse, off Scotland, and Longships Lighthouse, off Cornwall, at 23 and 25 knots. After traveling a total of 300 miles (483 km), the Lusitania managed to reach an average speed of 25.4 knots (47.0 km/h), slightly higher than the 24 knots required by Cunard's contract with the Admiralty. The ship could stop in four minutes in 3⁄4 of a mile starting with a speed of 23 knots at 166 rpm. and then navigating applying full reverse gear. At 180 rpm, a spin test was performed and the Lusitania made a full circle one thousand yards in diameter in fifty seconds. The rudder required twenty seconds to turn hard to 35 degrees.

Finally, after successfully completing sea trials, the Lusitania was formally delivered to the Cunard Line on August 26, 1907.

Features

Design

The Cunard Line established a committee to decide the design of the new liners, of which James Bain, the company's Marine Superintendent, was president. Other members included Rear Admiral H.J. Oram, who had been involved in the design of steam turbine-powered ships for the Royal Navy, and Charles Parsons, whose company, Parsons Marine, was a producer of turbine engines.

Parsons maintained that he could design engines capable of maintaining a speed of 25 knots (46.3 km/h), which would require 68,000 shaft horsepower (50,014 kW). The largest turbine sets built so far had been 23,000 horsepower (16,917 kW) for the Dreadnought-class battleships, and 41,000 horsepower (30,156 kW) for the Invincible-class battlecruisers, which meant that the engines would be of a new design never before tested. The turbines offered the advantages of generating less vibrations than reciprocating engines and greater reliability in operation at high speeds, combined with lower fuel consumption. It was agreed that tests would be carried out by installing turbines on the liner RMS Carmania, which was already under construction. The results were positive: with the expected improvements in passenger comfort and operating economy, a ship was obtained that was 1.5 knots (2.8 km/h) faster than its sister ship, the Caronia, which had with a conventional propulsion system.

The Lusitania was designed by the naval architect Leonard Peskett, and named in honor of the ancient Roman province of the same name, located west of the Iberian Peninsula, in the region that encompasses the current south of Portugal and the Spanish province of Estremadura.

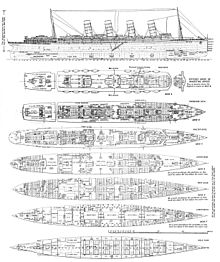

Peskett had designed a model of the proposed ship in 1902, which showed a three-funnel vessel. Later, in 1904, a fourth chimney was added, as the architect concluded that it was necessary to vent the gases expelled from the additional boilers installed. The original plans showed a ship powered by three propellers, but the number was increased to four because it was considered that the necessary power could not be transmitted through only three propellers. Four steam turbines would independently drive the four propellers, with additional reversing turbines to drive only the inner shafts.

The propellers were driven directly by the turbines, as sufficiently robust gearboxes had not yet been developed, and would not be available until 1916. Because of this, the turbines were designed to operate at a much lower speed than the normally accepted as optimal. Therefore, its efficiency was lower at low speeds than in a conventional steam engine, but significantly higher when the engines were operated at high speed, as was often the case with large ocean liners. The Lusitania was equipped with twenty-three double-ended and two single-ended boilers (fitting the forward space where the ship narrowed), operating at a maximum of 195 psi< /span> and containing 192 individual ovens.

The Admiralty contract required all machinery to be below the waterline, where it was considered best protected from gunfire, and the aft third of the ship under water was used to house the turbines, steering motors and four 375-kilowatt (503 HP; 510 HP) engines. The center half of the ship contained four boiler rooms, and the remaining space at the forward end of the ship was reserved for cargo and storage.

Coal bunkers were placed along the ship outside the boiler rooms, with a large transverse bunker immediately in front of boiler room n.° 1. In addition, the carbon was considered to provide additional protection to the central spaces against possible attacks. At the front were lockers to house the huge anchor chains, as well as ballast tanks to adjust the boat's trim.

The hull space was divided into twelve watertight compartments, two of which could be flooded without risk of the ship sinking, connected by 35 watertight bulkheads, which communicated with each other through hydraulically operated doors. The ship had a double bottom with the space divided into separate watertight cells. The ship's exceptional height was due to the six passenger accommodation decks located above the waterline, compared to the four common on ocean liners of the time.

At the time her construction was completed, the Lusitania became, for a brief period, the largest passenger ship ever built in the world, being surpassed by her sister ship, the Mauretania, when it entered in service. Passenger accommodation was 50% larger than that available on board her contemporaries, with accommodation for 552 passengers in first class, 460 in second and 1186 in third. Her crew consisted of 69 people on deck, 369 workers in the engine rooms and 389 employees to serve passengers. The ship had electric lighting, wireless telegraph, electric elevators, sumptuous facilities and a prototype of the current air conditioning system.

Interior

The Lusitania, the Mauretania and the Aquitania were sister ships and belonged to the British shipping company Cunard Line. All three were some of the most used ships for transporting passengers between the United States and Europe.

The Lusitania had 239 m in length, 31,550 t of displacement and 26 m beam. She was capable of transporting a total of 2198 passengers distributed in her different classes. The ship was designed with elegant lines, equipped with four chimneys, steam turbines and four propellers. In accordance with the regulations of the time, it had enough lifeboats, specifically sixteen. It was also the most modern of its time, with 17.5 watertight compartments, fire detectors, electrical control of lifeboats and a powerful T.S.H.

It differed from the Mauretania by having 1,500 t less displacement, having deck loungers, cylindrical vents (instead of the traditional ones) and a shorter forecastle, among other details.

At the time of their introduction to the North Atlantic route, both Lusitania and Mauretania had the most luxurious, spacious and comfortable interiors afloat. Cunard hired the Scottish architect James Miller to design the interiors of the Lusitania, while, for the Mauretania, the company chose the English architect Harold Peto. Miller employed plasterwork for the ship's interiors, while Peto made extensive use of wood paneling, resulting in the overall impression of the Lusitania's interiors being brighter than that of the Mauretania. It was thanks to this success that allowed the Lusitania to serve as inspiration for Cunard's rival company, the White Star Line, to design the luxurious interiors of its new ships: the Olympic, the Titanic and the Britannic. Passenger accommodation was spread over six decks; From the upper deck to the waterline were located the boat deck (deck A), the promenade deck (deck B), the shelter deck (deck C), the upper deck (deck D), the main deck (cover E) and the bottom cover (cover F). As seen aboard all ocean liners of the era, the spaces encompassing first, second and third class accommodations were strictly separated.

Most of the Lusitania's decorative elements had been designed and manufactured by the Bromsgrove Guild of Applied Arts, and some of the ship's furniture was supplied by the prominent English firm Waring & Gillow.

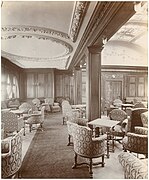

The first class rooms were in the central section of the liner, distributed among the five upper decks, most of them concentrated between the chimneys. Similar to what was present aboard major ships of the day, Lusitania's first-class interiors were decorated in a mix of historical styles.

First class dining room of Lusitania, 1907.

First class music room.

First class smoking room, 1907.

Verandah coffee shop, exclusively for the first class.

Reading and correspondence room.

First class staircase and elevator, 1907.

First class suites aboard Lusitania, c.1907.

The dining room was the most sumptuous of the public rooms found on the ship. It was built on two decks with an open circular well in its center and surmounted by an elaborate 8.8 meter (29 ft) dome, decorated with frescoes in the style of François Boucher, it was elegantly executed in the Louis XVI style. The lower floor, which measured 26 meters, had the capacity to accommodate 323 diners, with another 147 that could be accommodated on the upper floor, which measured 20 meters. The walls were decorated with carved mahogany panels in white and gold, with numerous Corinthian columns, required to support the upper floor.

The rest of the first class public rooms were located on the boat deck and consisted of a general lounge, a library, a reading room, a smoking room and a Verandah cafeteria with a terrace. The latter was an innovation never before seen on board a Cunard ship and, on days when weather conditions were favourable, one side of the cafeteria could be opened to give passengers the impression of having a snack. outdoor. This feature was little used due to the inclement weather of the North Atlantic.

The general hall was decorated in Georgian style, with inlaid mahogany panels surrounding a jade green carpet with a yellow floral pattern, measuring a total of 21 metres. The roof included a vaulted skylight rising 20 feet, adorned with stained glass windows depicting the months of the year. At each end of the room was a 13-foot-high green marble fireplace incorporating enamelled panels by Alexander Fisher.

The library had walls decorated with carved pilasters and moldings that marked the gray and cream silk brocade panels. The room was decorated with a pink carpet, curtains and silk upholstery in the Rose du Barry style. The chairs and desks were made of mahogany and the windows featured etched glass.

The smoking room was decorated in the Queen Anne style, with walnut paneling and Italian-style redwood furniture.

The first class staircase, like the famous Titanic staircase, connected the six decks where the passenger accommodations were located. On each level, the staircase had wide corridors and two elevators.

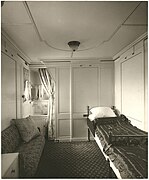

The first class cabins could range from a shared room to several private rooms with bathroom decorated in a diverse selection of decorative styles that included the two majestic suites, each with two bedrooms, dining room, living room and bathroom, with a decoration inspired by the Little Trianon of Versailles.

The second class facilities were limited towards the stern, behind the mast, where the cabins were located with the capacity to accommodate a total of 460 passengers. The public rooms were situated in divided sections of the boat and promenade decks. The design of the rooms for this class was assigned to the architect of the Clydebank shipyard, Robert Whyte.

Photograph of a second-class standard cabin on board Lusitania, 1907.

Entrance for second class passengers. At the lower level, the dining room was available for those passengers.

Living room for second class ladies, c.1907.

Second class general hall.

Second class eater of Lusitania. Its design and distribution resembled that of the first class installed.

The second class dining room, although smaller and simpler, featured a design that mirrored that of the first class dining room, with paneled walls carved with white plaster pillars. As was the case in first class, the dining room was located on the lounge deck. The smoking and ladies' rooms occupied the accommodation space on the promenade deck, with the general lounge on the boat deck.

The Cunard Line had never previously provided a general lounge for second class passengers. The living room, which measured thirteen meters, was equipped with mahogany wood tables, chairs, and sofas, placed on a pink-patterned rug.

The smoking room was 16 meters long, and was lined with mahogany panels, with a white plaster ceiling and dome. One of the walls was decorated with a mosaic depicting a river scene in Brittany, while the sliding windows in the living room were tinted blue.

Second class accommodation consisted of comfortable shared cabins, incorporating two to four berths, arranged on decks C, D and E.

Known to be the main source of income for shipping companies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, steerage experienced, with the introduction of ocean liners such as the Lusitania, a vast improvement in travel conditions that facilities offered to passengers.

The third class area of the Lusitania was quite popular among emigrant passengers, who chose to travel on this ship because its accommodations provided greater comfort compared to other liners of the time, where accommodation in Steerage consisted of large open spaces in which hundreds of people shared rooms, and hastily constructed public areas, often consisting of no more than a small portion of open deck space and a few tables set up inside the cabins.

In an attempt to break that standard, shipping companies such as Cunard Line, as well as other renowned companies such as the British White Star Line, or the German Hamburg Amerika Linie, began to design ships with more comfortable and healthier third class facilities., as in the case of the Lusitania, the Olympic or the Imperator.

As on all Cunard ships, third-class accommodation aboard Lusitania was located at the forward end of the ship, situated between decks C, D, E and F, and compared to other ships of the time, the rooms were more comfortable and spacious. The 80-foot dining room was located in the forward section of the ship, on the saloon deck. It was decorated with polished pine paneling, as were the other two public rooms: the smoking room and the women's drawing room. These last two were located on deck C of the ship.

When the Lusitania made voyages where third class capacity was reached, the women's lounge and smoking room could easily be converted into a large dining room to provide greater comfort for diners. Passengers ate at long tables with swivel chairs and meals were served in two sittings. A piano was provided for the use and enjoyment of passengers.

One of the features of the Lusitania's facilities that most attracted immigrants and lower-class travelers was that, instead of being confined to open dormitories with bunk beds, there were different cabins on board the ship that could accommodate two, four, six or eight berths.

Comparison with the Olympic class

In 1907 the White Star Line, the main British rival of the Cunard line, had ordered the construction of three new large liners in order to compete in size and luxury against the Lusitania and its sister ship, the Mauretania. These ships, known as the Olympic class, were 30 meters longer than the Cunard ships; and with 15,000 tons more, White Star's first two ships, RMS Olympic and RMS Titanic, had surpassed Lusitania and Mauretania as the ships largest passenger car ever built.

Although significantly faster than the Olympic class ships, the speed of Cunard's vessels was not sufficient to allow the company to operate a weekly transoceanic service with only two ships sailing from both sides of the Atlantic. The company required a third vessel to ensure a rotating weekly service and, in response to White Star's announced plan to build the Olympic class, ordered the construction of a third liner: the RMS Aquitania. Like the new White Star ships, the Aquitania was slower than the Lusitania and Mauretania, but she was more luxurious and larger.

The White Star ships, being larger in size, offered more amenities than the Lusitania and the Mauretania and, in contrast to the latter, offered a swimming pool, Turkish and electric baths, gym, squash court, large rooms reception, independent restaurants and a much larger number of cabins with private bathrooms.

The strong vibrations produced by the steam turbines would affect the structure of the Lusitania throughout its career. When the ship sailed at maximum speed during her sea trials, the resulting vibrations were so severe that several of the second and third class cabins were in danger of being disabled. In contrast, the Olympic class ships used two traditional reciprocating engines and a single turbine for the central propeller, which greatly reduced vibration aboard these vessels. Due to her larger tonnage and wider beam, the Olympic and Titanic had greater stability at sea.

The Lusitania had a straight-stemmed bow, unlike the White Star ships, which had angled bows that allowed it to dive through a wave instead of riding over it. This would, as an unforeseen consequence, cause the Lusitania to list alarmingly, allowing huge waves to splash over the bow and forward part of the ship's superstructure, which would become a major factor in the damage it sustained to the bridge in January 1910, after being hit by a giant wave.

The Olympic class ships also differed from the Lusitania and Mauretania in the way they were compartmentalized below the waterline. The White Star ships were divided by transverse bulkheads, while the Lusitania, in addition to having transverse bulkheads, also included longitudinal bulkheads along the length of the ship on each side, between the engine rooms and the coal bunkers. The British commission that, in 1912, had investigated the sinking of the Titanic, heard testimony about the flooding of coal bunkers outside the longitudinal bulkheads. Being of considerable length, in the event of flooding, they could increase the list of the ship and make it "impractical" the lowering of the lifeboats on the other side. This finally happened in 1915 when the Lusitania was torpedoed.

The stability of the ship was insufficient for the arrangement of its bulkheads: flooding of three of the coal deposits on one side could result in a negative metacentric height. In contrast, the stability of the Olympic class was designed such that there was very little risk of uneven flooding and overturning. This is evident in the case of the Titanic, which sank with only a few degrees of list thanks to its good stability.

As was the case on board ocean liners of the time, at the time of its maiden voyage, the Lusitania did not carry enough lifeboats for all its passengers, officers and crew on board, as it was believed that, in In the event of an accident, help would always be nearby and the few boats available would be enough to evacuate everyone.

After the Titanic disaster, the Lusitania and Mauretania were fitted with six additional wooden boats, increasing the total number from 16 to 22 davit-rigged lifeboats. The total capacity was supplemented by the addition of 26 folding launches, eighteen stored directly beneath the conventional boats and eight on the aft deck. The folding boats were built with hollow wooden bottoms and canvas sides, and had to be assembled if needed.

This contrasts with the measures taken by White Star regarding the Titanic's two sister ships, Olympic and Britannic, which received a full complement of lifeboats, all rigged under davits. This difference would have contributed greatly to the large loss of life during the sinking of the Lusitania, as there was not enough time to assemble the folding rafts due to the speed of the sinking. Compared to the Lusitania tragedy, during the sinking of the Britannic in 1916, the crew had more time to organize and execute the evacuation (the time it took for the Britannic to sink was three times longer than that for the Lusitania), achieving thus saving a greater number of people.

Service

Beginnings

The Lusitania made its maiden voyage on September 7, 1907, under the command of Cunard Line Commodore James Watt, traveling between Liverpool, Queenstown and New York. A crowd of 200,000 people gathered in the port of Liverpool to bid farewell to the largest ship ever built, which set sail at 9:00 p.m. heading to the Irish port of Queenstown (now Cobh), where it would make a stopover to pick up more passengers.

At 12:10 h the next day, it continued its course to New York across the Atlantic. In the first 24 hours he achieved 561 miles (903 km), adding to the total daily miles traveled over the next four days: 575, 570, 593 and 493 miles, before reaching Sandy Hook, New Jersey, at 9:05 a.m. on September 13, taking 5 days and 54 minutes to cross the Atlantic. In New York Harbor, a crowd of people gathered on the banks of the Hudson River from Battery Park to Pier 56 to greet the Lusitania upon its arrival in port, so police went to the scene to control the crowd and prevent incidents. After docking at the New York docks, the ship remained open to the public for the following week, being available for guided tours.

At 3 p.m. on September 21, the ship departed on its return trip to Great Britain, arriving in Queenstown during the early hours of September 27, and Liverpool during the afternoon of that same day. After having to delay her arrival due to fog, the Lusitania took 5 days, 4 hours and 19 minutes to complete her return journey to Europe.

In October 1907, during its second voyage, the ship arrived in New York after making a voyage that lasted 4 days, 19 hours and 53 minutes, managing to beat the record time set by the German liner Deutschland, of 5 days, 11 hours and 54 minutes, which managed to recover the precious Blue Band for the United Kingdom. On this record-breaking trip, the average speed achieved was 23.99 knots (44.43 km/h) westbound and 23.61 knots (43.73 km/h) eastbound. The Lusitania retained the prize and the record for the fastest eastbound crossing until December of that year, with the entry into service of her sister ship, the Mauretania.

Nevertheless, the Lusitania held the record on the westward route until July 1909, when, after improving her own speed record with an average of 25.85 knots (47.87 km/h), she was definitively taken away by the Mauretania after making a faster crossing, maintaining the prize for the next twenty years.

During her eight years of service, the ship crossed the Atlantic 201 times, on the Cunard route between Liverpool and New York, carrying a total of 155795 passengers on their westbound and 106180 eastbound crossings.

Sinking

On May 7, 1915, the Lusitania was torpedoed at 2:00 p.m. off the Old Head of Kinsale lighthouse, off the Irish coast, by the German submarine SM U-20, commanded by Captain Walther Schwieger. In just a few minutes she had listed 25°, making it very difficult to lower the lifeboats. In just eighteen minutes, the ship had sunk.

After the explosion of the torpedo on the hull of the ship, a second explosion was reported, the cause of which is not known with certainty, although none of the elements reported among the cargo had sufficient explosive power to cause it. Because this explosion was the main cause of her rapid sinking, it has given rise to multiple speculations. The shipwreck caused the death of more than 1,198 passengers including 100 children. 761 people survived. The death of 128 American citizens was probably one of the causes of the US entry into World War I two years later.

The legal owner of the wreck, Gregg Bemis, financed an underwater expedition in 2011 whose main purpose was to determine the real causes of the sinking. For this he hired the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory , which did a previous study that included global positioning satellite information, multibeam data and side-scan sonar images. The expedition took place in August and was monitored by the Irish Naval Service. The expedition found hundreds of.303 caliber cartridges but no evidence of artillery ammunition or explosives. The detailed analysis of the information obtained and the use of computer models led the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory technicians to conclude that the second explosion was most likely due to the explosion of a boiler after make contact with the cold water of the ocean.

Illustration of the torpedoing of the ship.

Diagram that describes the torpedoing of Lusitania.

Shipwrecked.

Cover of the New York Times announcing the news of the torpedoing and shipwreck of Lusitania, published the day after the disaster.

World War I cartel calling for justice for the victims of the shipwreck.

Monument in memory of the 1198 victims of sinking in Cobh, Ireland.

Wreck

The wreck of the Lusitania is located 11.5 nautical miles from Kinsale, 93 meters deep, lying on its starboard side. Although the bow is still recognizable, the ship is almost completely chamfered on itself and its superstructure has collapsed on the seabed. She has several fishing nets tangled in her frame and around her are undetonated depth charges.

After the sinking, the Liverpool War Risk Insurance Association, an organization belonging to the British government, bought the rights to the wreck, after paying the amount corresponding to the ship's insurance, although it never made any dives. nor attempt at recovery.

In 1967, the Liverpool War Risk Insurance Association sold the diving and salvage rights at a silent auction. It was purchased by a United States Navy diver named John Light. Light had dived, on his own and with basic diving equipment, to the wreck site 42 times between 1960 and 1962. To finance the expedition, Light partnered with businessmen George Macomber and Gregg Bemis, but the company collapsed. and Light had to assign the rights to Macomber and Bemis without making any dives.

Its new owners showed no interest in the wreck until 1982 when Bemis learned that, due to its cargo of bronze ingots, it was valued at twelve million dollars.

Bemis bought out Macomber and began organizing an expedition in order to recover it, dismantle it and sell it for scrap. To find out what was really at the wreck site, Bemis hired Oceaneering International, an American company based in Houston, which recovered three propellers, porcelain, a bell and a whistle. But then he had to battle legally against the British government, which claimed ownership of the remains. Finally, the court confirmed Bemis' ownership in 1986; Although, then, a change in the territorial waters of Ireland placed the ship under the jurisdiction of this country, which declared it an "archaeological site" and prevented any attempt to alter it. Because of this, Bemis renounced any attempt to obtain financial benefit.

Improvements in underwater exploration technology in the early 1990s led Bemis to consider diving for scientific purposes. To do this she teamed up with oceanographer Robert Ballard, discoverer of the Titanic wreck, who produced a documentary about the Lusitania, which aired in 1994 on National Geographic. The broadcast of the documentary attracted public attention and it was soon reported that illegal diving and looting were taking place. These complaints brought several people to justice and the recovered remains had to be handed over to museums. This led Ireland's Ministry of Culture to increase controls and issue a protection order over the wreck, requiring all dives to require a licence.

In order to recover remains, the 2011 expedition required an agreement with the Irish Underwater Archaeological Unit and the National Museum of Ireland. During the same, the bridge telemotor, a windshield, two square and two round portholes were rescued.