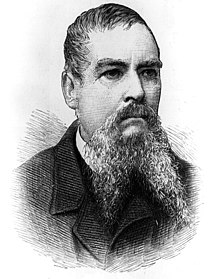

Richard Francis Burton

Richard Francis Burton (Torquay, England, March 19, 1821 – Trieste, Austro-Hungarian Empire, October 20, 1890) was a British consul, explorer, translator and orientalist, although he considered himself himself fundamentally an anthropologist and cultivated occasional poetry. He became famous for his explorations in Asia and Africa, as well as for his extraordinary knowledge of languages and cultures. According to a recent count, he spoke twenty-nine European, Asian, and African languages.

Biography

He lived in India for seven years, where he had the opportunity to learn about the customs of the oriental peoples. He completed the maps of the area adjacent to the Red Sea on behalf of the British government, interested in trade with the area. He traveled alone to see Mecca, for which he disguised himself as an Arab, a feat about which he himself wrote in The Pilgrimage to Al-Medinah and Meccah ( My pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina). He is indebted for the first full English translation of The Thousand and One Nights and the Kama Sutra, as well as a brilliant translation of the Portuguese epic and classic poem Os Lusíadas , by Luís de Camões, into English. Together with John Hanning Speke he traveled to Africa where he discovered Lake Tanganyika.

He also traveled throughout the United States, where he described the Mormon community in his book The City of the Saints, and part of Brazil. He was a co-founder of the London Anthropological Society with Dr. James Hunt. He was reviled by the puritanical British society of his day for holding unorthodox views on female sexuality and polygamy as well as for having married a Catholic citizen, Isabel Arundell. He was British consul on the African island of Fernando Poo, in Santos (Brazil), Damascus (Syria) and Trieste (Italy), he was knighted in 1866.

Youth and education (1821–1841)

Burton was born in Torquay, Devon at 9:30 p.m. on 19 March 1821 (in his autobiography, he erroneously states that he was born in the family home of Barham House in Hertfordshire). His father, Captain Joseph Netterville Burton, was a British Army officer of Irish origin. His mother, Martha Baker, was the heiress of a wealthy Hertfordshire family. He had two siblings, Maria Katherine Elizabeth Burton and Edward Joseph Burton.

Burton's family traveled extensively during his childhood. In 1825 they moved to France (Tours, Orleans, Blois, Marseille) and then to Italy (Livorno, Pisa, where the young Burton broke a violin over the head of his music teacher, Siena, Perugia, Florence, Sorrento and Naples, not to mention the excursions of one or two weeks to other cities); in Naples the brothers Richard and Edward visited their first brothel. Burton's first formal education was received by various tutors hired by his parents, showing early on a great facility for languages: he quickly learned French, Italian and Latin. It was rumored that in his youth he had an affair with a young gypsy, eventually learning the rudiments of her language (Romani). This might perhaps explain why he was later able to learn Hindi and other Hindustani languages with almost supernatural speed, since Romani is related to that language family.

The comings and goings of his youth may have led Burton to regard himself as an outsider for much of his life. As he himself said: "Do what your manhood pushes you to do, expect no approval except from yourself...".

Burton entered Trinity College, Oxford, in the autumn of 1840. Despite his intelligence and ability, he soon became estranged from his professors and peers. He found himself absolutely alone without his family for the first time, and it is said that during his first year he challenged another student to a duel after the latter made fun of his mustache. Professor Greenhill then introduced him to the Spanish Arabist Pascual de Gayangos and he sparked Burton's innate curiosity towards Arabic, which he began to study ardently. John Varley encouraged him to study the occult and he also spent some time learning falconry and fencing, the latter subject in which he would become one of the first swordsmen of the British Empire and to which he would consecrate The Book of the Sword (1884). In 1842 he participated in a cross-country horse race (the famous steeplechase , in deliberate violation of university regulations, as it was considered typical of people of low social class) and then he dared to propose the academic authorities to allow students to attend such events. Expecting to be suspended, that is, expelled with the possibility of readmission, as he had been with other less provocative students who had attended the hunt, Burton was nevertheless permanently expelled from Trinity College. In a final contempt for the environment he had learned to denigrate, Burton is said to have vandalized the college's flower beds with his horse and carriage when he left Oxford.

Military career (1842–1853)

"Good for nothing, except to be shot for sixpence a day", Burton enlisted in the army of the East India Company. He had hoped to take part in the first Afghan war, but the conflict had ended before he reached India. He was posted to the 18th Bombay Native Infantry (based in Gujarat) under the command of General Charles James Napier. His service in India was eventful; His continual criticism and insults of a British community that he viewed as irresponsible at heart and frivolous in his ways earned him a dark reputation. In his many writings, he harshly criticized British colonial policy, as well as the modus vivendi of Company officers: "What can you expect from an Empire supported by shopkeepers."

During his stay he became fluent in Hindi, Gujarati and Marathi as well as Persian and Arabic. His studies of Hindu culture reached such a point that "...my Hindu teacher officially allowed me to wear the janeu (Brahmin lace)", although the truth of this statement has been questioned since this would have required long study time, fasting, and partial shaving of the head. Burton's interest in Hindu culture and his active participation in the country's rituals and religions earned him rejection from some of his military comrades, who accused him of "going native," going so far as to christen him "the black man." white".

Burton kept a group of tame monkeys with the idea of learning their language. He also earned the nickname "Dick the Ruffian" for his "demonic ferocity as a fighter and because he had fought more enemies in single combat than anyone else." man of his times".

He was appointed to participate in the mapping of Sindh and learned the use of measuring instruments, knowledge that would come in handy later in his exploring career. At that time he began to travel in disguise. He adopted the alias Mirza Abdullah and often managed to remain unnoticed among the natives, to the point where his fellow officers mistook him for one of them. It was thereafter that he began working as an agent for Napier and, although the details of his activities are not known, it is known that he participated in the undercover investigation of a brothel said to be frequented by English soldiers and in which the prostitutes were young. His lifelong interest in various sexual practices led him to write a detailed report on Karachi's brothels that was to get him into trouble when some of the readers of the report (which he had been assured would be kept secret) arrived. to believe that Burton himself had participated in some of the practices described in his texts.

In March 1849 he returned to Europe on sick leave. In 1850 he wrote his first book, Goa and the Blue Mountains, a guide to the regions of Goa and the seaside resort of Ooty, where he hoped to recover from an illness contracted during his stay in Baroda. He traveled to Boulogne to visit his fencing school and it was there that he first met his future wife Isabel Arundell, a young Catholic woman from a good family.

First explorations and trip to Mecca (1851–1853)

Moved by a desire for adventure, Burton secured approval from the Royal Geographical Society to explore the area and secured authorization from the Board of Directors of the British East India Company for indefinite leave from the army. His time in Sindh had prepared him well for his Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca and, in this case, Medina) and his seven years in India had familiarized him with Muslim customs and behavior. It was this journey, begun in 1853, that made Burton famous. He had planned it when he was traveling in disguise among the Muslims of Sindh and had prepared himself thoroughly for the task with study and practice (including getting himself circumcised to further reduce the risk of discovery, as one of his role models, the spy, had already done). Spanish Domingo Badía, "Ali Bey").

Although Burton was not the first non-Muslim European to perform the hajj (such an honor is due to Ludovico de Verthema in 1503), his pilgrimage is the most famous and best documented of its time. He adopted various guises including that of "boorish" (modern Pashto) to account for any peculiarities of his speech, but even so he had to demonstrate a keen understanding of intricate Islamic ritual and familiarity with the minutiae of Oriental manners and etiquette. Burton's journey to Mecca was quite eventful and his caravan was attacked by bandits (a common experience at the time). As he himself wrote: «[Although] neither the Koran nor the sultan calls for the death of the Jew or Christian who crosses the columns that mark the limits of the sanctuary, nothing can save a European discovered by the mob. or to one who after the pilgrimage has shown himself to be unfaithful". The pilgrimage entitled him to the title of Hajji and to wear a green turban. Burton's own account of his journey appeared in his 1855 work The Pilgrimage to Al-Medinah and Meccah ( My pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina ).

First period of explorations (1854–1855)

In March 1854 he was transferred to the political department of the East India Company. The exact nature of his work at this time is uncertain, although it seems likely that he was spying for General Napier. It was in September of that year that he first met Captain (then Lieutenant) John Hanning Speke, who would accompany him on his most famous exploration. His next trip led him to explore the interior of the Somali country (modern Somalia), as the British authorities wanted to protect trade through the Red Sea. Burton set out on the first part of his solo journey. He made an expedition to Harar, the Somali capital, which no Europeans had entered (in fact there was a prophecy that the city would fall into decay if a Christian was admitted inside).

The expedition lasted four months. Burton not only reached Harar, but was presented to the emir, and remained in the city for ten days. There he was one of the first (William George Browne had anticipated him in 1799) to describe the Central African custom of clitoridectomy or female genital cutting. The return was plagued by problems due to lack of supplies and Burton wrote that he would have died of thirst if he had not seen desert birds, realizing that they indicated the proximity of water.

After this adventure he set out again, this time accompanied by Lieutenants John H. Speke, G. E. Herne, and William Stroyan and a number of Africans employed as porters. Shortly after leaving, however, the expedition was attacked by a group belonging to a Somali tribe (officials estimated their number at about two hundred). In the engaged combat Stroyan was killed and Speke captured and wounded in eleven parts before managing to escape. Burton was skewered with a spear, the point of which entered his cheek and protruded out the other, an injury that left a significant scar easily visible in portraits and photographs. He nevertheless managed to escape, with the weapon piercing his head. But the authorities severely judged the incident, considering it a failure, and an investigation was ordered, which for two years tried to find someone responsible for the disaster, something to which it was considered that Burton's temperament and behavior could have led him. And while he was largely exonerated of any blame, the fact in no way helped boost his career. Burton describes this shocking attack in his 1856 work First Footsteps in East Africa .

In 1855 he rejoined the army, going to the Crimea in the hope of active service in the Crimean War; he was assigned spy duties. He served on the staff of Beatson's Horse, a corps of local bashi-bazouk warriors under the command of General Beatson, in the Dardanelles. The corps was disbanded following a "riot" after they refused to carry out orders and Burton's name was mentioned (to his detriment) during the ensuing investigation.

Exploration of the lakes of Central Africa (1856–1860)

In 1856, the Royal Geographical Society funded another expedition in which Burton set out from Zanzibar to explore an "inland sea" that was known to exist. His mission was to study the local tribes and find out what exports could be made from that region. It was hoped that the expedition could lead to the discovery of the sources of the Nile, although that was not the explicit objective. Burton had been told that only a fool would say that the expedition sought to find the sources of the Nile because if the expedition ended without finding them, it would be considered a failure regardless of any other discoveries.

Before leaving for Africa, Burton proposed to Isabel Arundell, and the two became secretly engaged. Her family would never have agreed to the marriage since Burton was neither Catholic nor wealthy. Speke accompanied him again, and on June 27, 1857, they left the east coast of Africa in a westerly direction, in search of the lake or lakes. They were greatly aided by the experienced local guide Sidi Mubarak (also known as "Bombay"), who was familiar with some of the region's customs and languages. From the start, the journey into the interior was plagued by problems such as the recruitment of reliable porters and the frequent theft of materials and supplies by deserters from the expedition. What's more, both explorers fell victim to tropical diseases during the voyage. Speke was left blind for part of the journey and deaf in one ear from an infection caused by attempts to remove a beetle that had gotten into it. And Burton was left so weak that he was unable to walk much of the way and had to be carried by porters.

The expedition reached Lake Tanganyika in February 1858. Burton was amazed by the sight of the vast lake, but Speke, still temporarily blind, was unable to appreciate the magnitude of the lake. At this point, much of his surveying equipment had been lost, damaged, or stolen, and they were unable to complete the surveying of the area as well as they would have liked. Burton fell ill again on the return voyage and Speke continued exploring without him, making a trip north and finally locating the great Lake Victoria. Lack of supplies and suitable instruments prevented him from surveying the area, but he became convinced, in his heart of hearts, that the lake was the long-sought source of the Nile. Burton's description of this voyage is given in The Lake Regions of Equatorial Africa, 1860. Speke expounded his own version of the voyage in The Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1863).

Both Burton and Speke were left in poor health after their difficult expedition and returned home separately. As was his habit, Burton made detailed notes, not only on the geography, but also on the languages, customs, and sexual habits of the people he encountered. Although it was the last of Burton's great expeditions, his geographical and cultural notes were of great use to subsequent expeditions by Speke and James Augustus Grant, Samuel Baker, David Livingstone, and Henry Morton Stanley. The Speke and Grant expedition (1863) also set out from the east coast near Zanzibar and rounded the west shore of Lake Victoria to Lake Albert, finally returning triumphantly up the Nile. Crucially, however, they lost the track of the river's course between Lake Victoria and Lake Albert. This left Burton and others in doubt that the sources of the Nile had been conclusively identified.

Burton and Speke

Burton and Speke's discovery of Lakes Tanganyika and Lake Victoria was arguably their most celebrated exploration, but what followed was a bitter and protracted public dispute between the two men that seriously damaged Burton's reputation. Judging from some surviving letters, it appears that Speke disliked and mistrusted Burton even before they began their second expedition together.

There are several reasons why they drifted apart. In the Somali adventure, Speke had the handicap of being a newcomer among old friends, as well as being the replacement for Lieutenant Stocks who, according to Burton, was 'everyone's favourite'. Speke did not speak Arabic and, despite having spent ten years in India, he had very little knowledge of the Hindustani languages. It seems obvious that the two were of very different personalities, with Speke being more in keeping with the prevailing Victorian morality of the time. This was undoubtedly the cause of professional rivalry. Some biographers have suggested that certain friends of Speke (notably Laurence Oliphant) sowed discord between them. It also appears that Speke resented the role of expedition leader that had been given to Burton, claiming that leadership was only nominal and claiming that Burton was virtually an invalid throughout the second part of the expedition. There were also problems over the debts incurred by the expedition that remained unpaid when leaving Africa: Speke claimed that Burton was solely responsible for those debts. Finally, there was the matter of the discovery of the sources of the Nile, perhaps the greatest prize any explorer of his day could claim. Today Lake Victoria is known to be a source, but at the time it was still a controversial issue. Speke's expedition there was undertaken without Burton (who was incapacitated by various illnesses at the time) and his surveying of the area was by necessity rudimentary, so he left the matter unresolved. Burton (and indeed many eminent explorers such as Livingstone) remained skeptical that the lake was the true source of the Nile.

After the expedition, the two traveled to England separately. Speke arrived in London first, and despite a prior agreement between them that the two would give their first public speech together, Speke gave a lecture to the Royal Geographical Society in which he proclaimed his discovery, Lake Victoria, to be the source of the Nile. When Burton arrived in London he found Speke celebrated as a hero and felt his role reduced to that of a sick companion. Furthermore, Speke was organizing other expeditions to the region on which he certainly did not plan to take Burton.

In the months that followed, Speke constantly attempted to damage Burton's reputation, going so far as to claim that Burton had tried to poison him during the expedition. Meanwhile, Burton argued against Speke's claim to have discovered the sources of the Nile by saying that his evidence was inconclusive and Speke's measurements were imprecise. It is notable to note that on Speke's expedition with Grant, the latter had the latter sign a statement saying, among other things: "I renounce all my rights to publish... my own account [of the expedition] until approved by the captain." Speke or by the Royal Geographical Society".

Speke and Grant carried out a second expedition to prove that Lake Victoria was the true source of the Nile, but again problems with surveying and measurements meant that no one was convinced that the matter was definitively settled. On September 16, 1864, Burton and Speke were to debate the issue of the sources of the Nile before the British Association for the Advancement of Science, at the association's annual meeting in Bath. However, the day before, Speke had died from a self-inflicted shotgun blast while hunting on the property of a nearby relative. There were no direct witnesses to the shooting and there has been widespread speculation that he may have committed suicide. However, the coroner declared that it was a hunting accident. Burton was in the lecture hall to give his speech when news of Speke's death reached him, and, considerably distraught, decided not to deliver his speech.

Diplomatic service and academic studies (1861-1890)

Richard Burton made friends in multiple environments; among them, perhaps the most respectable was that of the Cambridge apostle Monckton Milnes, owner of one of the largest private libraries in England in four languages, but also the largest collection of erotic literature in the country, which served Burton to document his erudition. of erotomaniac; that one brought together a room of intellectuals that Burton used to frequent. He was also acquainted with the perverted pornographer Frederick Hankey, who bound some of his books in human skin, and was a friend of the masochistic decadent poet Swinburne, who also frequented Milnes's drawing room. All these bad companies did not deter Isabel Arundell, and in January 1861 she secretly married (preventing her family's opposition) to Richard Francis in a ceremony in which he did not want to assume his wife's Catholic faith, at least in that moment; Throughout her life she would flirt with other beliefs such as the occult and Sufism, without clearly opting for any.

In 1862 Burton entered the diplomatic service as British consul in the Spanish colony of the island of Fernando Poo (now Bioko, in Equatorial Guinea), where the climate and tropical diseases had dangerously decimated the European population; It was certainly not a good destination, and for this reason Isabel did not accompany him for most of the time, which, moreover, Burton took advantage of to explore black Africa; he was, however, on vacation for a time with Isabel on the island of Madeira; around this time he took a trip up the Congo River to the Yellala Falls and beyond, and described it in his book Two Voyages to the Land of Gorillas... (1876). In September 1864 he was appointed her Majesty's consul at Santos, then a humble Brazilian port two hundred and thirty miles south of Rio de Janeiro, and the couple met there in 1865; he traveled through the mountains of Brazil and by canoe up the San Francisco River, from its source to the Paulo Afonso waterfall. In 1868 he resigned, among other things because he and his wife had suffered from all kinds of tropical diseases; He did, however, have time to visit the Paraguayan war zone twice: in 1868 and in 1869, something he described in his Letters from the Paraguayan battlefields (1870), being impressed by the savagery of the contention

In 1869, when he was in Lima, he was appointed consul in Damascus with a thousand pounds pay, an ideal position for him, who was an expert orientalist; Before, however, going there, he walked through Córdoba, Mendoza and Buenos Aires, and it is still said that he went to Chile, although there is no sure proof; he was received by Bartolomé Miter and by President Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. After passing through London, he went to Vichy for a few weeks to take the waters with his friend and correspondent, the great decadent poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, then submerged in the swamps of alcoholism, and tried unsuccessfully to rehabilitate him by setting himself an example, since in that time and with a great effort of will he managed to give up the drink. There he also met the painter Frederic Leighton and the opera singer Adelaide Kemble Sartoris, and together they celebrated unforgettable evenings; but his wife Elizabeth went to get him out of there, leaving both husbands to the French Alps and Turin, and then to Damascus.

She spent two terrible years there, especially for Isabel, who found that place much more inhospitable than Brazil; However, they became friends with Jane Digby and with Abd al-Qádir, an exiled Algerian political leader. She tried to keep the peace between the three religions; however, she antagonized much of the Jewish population over her opposition to the British consulate's custom of taking action against loan defaulters; Burton saw no reason to continue this policy, which caused great hostility; he was removed as consul and replaced by Thomas Jago, returning heartbroken to London without even trying to defend himself, until her wife Isabel took up the cause of her rehabilitation by visiting her enemies and the wives of her enemies; and it was quite easy for him: numerous people were propitious to testify and write letters in praise of him and of his honesty and rectitude; what's more, many Muslim merchants (not so the Jews) believed him responsible for the fall of the hated Rashid Pasha and asked for his return; even the Protestant missionaries and the press itself changed their minds; Lord Granville offered him the consulate in Pará, in northern Brazil, which he refused as a lesser post, and when they gave someone else the post in Tehran, he took offense at it.

The Damascus experience made Burton an anti-Semite and he wrote about it in The Jew, which he failed to publish until Elizabeth's biographer W. H. Wilkins did in the midst of the Dreyfus affair in 1869. In 1872 a businessman financed a trip to Iceland for him to go to inspect the possibility of opening sulfur mines there, also offering him a large sum if he found exploitable deposits, and about this trip he wrote another book, Ultima Thule, although there was no luck and this trip ended up being especially unpleasant for someone used to the light of the tropics; that same year he was reassigned to the Adriatic port city of Trieste, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, albeit at a lower salary: six hundred pounds; he had sought a consulate in Morocco, but had to make do, since the post was much quieter and he could devote himself to writing and travelling. During one in London he underwent surgery on a small tumor that a blow had produced on his back.

His marriage to Isabel then seemed like a mere coexistence between two brothers who barely met by chance, as happened once in Venice when both of them bumped into each other without knowing where in Europe they were, but it was he who shunned her the most: "I am an incomplete twin and she is the fragment that I lack," he once said; he avoided her for five months in 1875; seven between 1877 and 1878 and six in 1880, but as he grew older her dependence on her became deeper and more apparent. In Trieste they lived, when they lived together, on the top floor of a hotel, in a spacious apartment with ten rooms that they gradually expanded to twenty-seven, most of them to fill them with books (in 1877 they already owned eight thousand) and with the collection of Isabel's religious objects and the tapestries, enamels, rugs, trays and oriental divans of Richard Francis, who also occupied the tables for the materials for his works. Later, as they received several inheritances, they had enough money to buy a palazzo. In addition, they held a gathering with fifteen friends at the town hall, and his wife another with her friends on Fridays.

Burton befriended professors Luigi Calori, Ariodante Fabretti, and Giovanni Capellini, rector of the University of Bologna, and conducted archaeological excavations on the Istrian peninsula, describing his findings in an article; he was also interested in the mystery of the Etruscan in his book Etruscan Bologna , without getting anything right; this work was met with poor reviews, although it was sought for in Trieste by Archibald H. Sayce, Arthur Evans, and Heinrich Schliemann; on the contrary, his wife's book The inner Life of Syria, Palestine, and the Holy Land , published the same year as Etruscan Bologna (1876), reached a resounding success and Burton even felt jealous. Between 1872 and 1889 he published eight new works in thirteen volumes, a total of five thousand pages, and in 1875 he began writing his Autobiography, which would be plagiarized and altered when it was published under the name of his presumed biographer Francis Hithcle, for which he cut it short. His most important works in these years were, on the one hand, the beginning of his monumental translation from Arabic of The Thousand and One Nights (16 vols. published between 1885 and 1888), with its extensive notes and accompanying essays, and on the other a scholarly work that went almost unnoticed, Unexplored Syria.

The first work was composed on purpose against the modesty of the former translator Edward William Lane, recently deceased in 1876, who had devastated the text, and included an essay that Burton flatly titled Pederasty and which in its separate English and American editions usually appears under the title The sotadic zone, a pioneering work in studies on homosexuality and "deviant" sexual practices, which would later acquire such importance with psychoanalysis and modern sexology, anticipating the study on homosexuality by Havelock Ellis by almost thirteen years with which this famous English sexologist decided to begin his studies in sexual psychology, and by almost fifteen years the appearance of the Yearbook of Magnus Hirschfeld, when he began to publish his studies on the zwischenstufen or "intermediate sexual types". This earned Burton a wide reputation as a homosexual in the narrow, Victorian society of his day, a fame that had been building up precisely from the time he himself confessed to having first made contact with the «execrabilis family pathicorum» (the «homosexual family»), that is, during Napier's campaign in Sind, in the years 1844-45. The second work is important because it transcribed several epigraphic texts from four basalt tablets that the Swiss orientalist Johann Ludwig Burckhardt had discovered in 1812 in the city of Hama; his theory that they were in the Hittite language turned out to be correct, and despite the tremendous criticism he suffered for it, he ultimately got his way. He also spoke of a "Moabite tombstone" that ended up in the Louvre and that was the first archaeological discovery that documented an event narrated in the Bible, the triumph of Mesha, king of Moab, over Omri, king of Israel.

With his last breath of life, in 1888 he decided to translate Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron without censorship but, as John Payne anticipated him, he opted for another more lurid and indecent one from one of the novellieri disciples of the same, Il Pentamerone (o Lo cunto de li cunti) by Giovanni Batista Basile, first printed in Naples in 1637. The translation of the strongest passages shows that he had not forgotten the street slang he had learned in Naples as a young man; Thus, when describing a fight between an old woman and a boy who had broken his pitcher with a stone, he offers us the following dialogue:

"Ah, manso, mosquitoes, meacamas, dancecabras, persecutor of water, hanged rope, mule mestiza, zanquilargo: from now on, to stick with you the paralysis and your mother finds out about bad news... Beautiful pimp, son of a bitch!" The boy, who had little beard and even less discretion, when he heard this tide of insults, paid him with the same coin saying, "Do you not know how to hold your tongue, the devil's grandmother, the bull's vomit, suffocating, mop, old bangs?"

Burton suffered from insomnia and ate breakfast at five in the morning; he walked through the mountains using an iron cane as heavy as a rifle, practiced an hour of fencing every day (he came to be considered the third swordsman of the British Empire) and in summer he went swimming. The Burtons made occasional trips to Venice, Rome, London, and their favorite German resorts. But in his last years this rosy health quickly collapsed and the famous explorer died in 1890 corroded by gout, circulatory diseases, angina pectoris and the sequelae of poorly cured tropical diseases; his remains were repatriated to London and, as the government did not authorize his body to rest in the pantheon of illustrious men in Westminster, he ended up resting in Mortlake (Surrey), in a famous Bedouin tent-shaped tomb designed by his wife Elizabeth, who took advantage of her death to burn many of her husband's writings (including most of his diaries), which she considered offensive to his memory and good manners. She wrote one of his biographies and also lies there with him.To the Royal Anthropological Institute of London went the gigantic and select private library of Burton and a good part of his manuscripts. Much of his correspondence with the erotomaniac Monckton Milnes is preserved at Trinity College, Oxford, and most of the correspondence between him and his wife and other manuscripts are at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California.; other documents and manuscripts are in private collections.

Richard Burton published forty-three volumes on his expeditions and travels; he wrote two books of poetry, more than one hundred articles, and an autobiography. In addition, he translated into sixteen rigorously annotated volumes The Thousand and One Nights, six works of Portuguese literature (including the classic epic poem Os Lusiadas, by Camoens), two of Latin poetry (the Elegies of Catullus, the Priapeos) and four of Neapolitan, African and Hindu folklore; all keep abundant annotations that attest to his erudition. Perhaps the best portrayal of the personality of Richard Francis Burton was given in James Sutherland Cotton's obituary article for Academy magazine:

He liked to consider himself an anthropologist and, in using this term, what he wanted to indicate was that he considered as his land all concerning men and women. He refused to admit as vulgar or dirty anything that humans did, and dared to write (to circulate privately) the results of his extraordinary experience... All he said and wrote was wearing the seal of his virility... He hid nothing; he didn't boast of anything... His intimates knew Burton was bigger than what he said or wrote.James Sutherland Cotton

His private library, considered in its day one of the most complete in Europe, amounted to some eight thousand volumes.

"Dick the Ruffian". Public scandals

Richard Burton was always a controversial figure and there were some in Victorian society who would leave a room rather than be seen in his company, but for that very reason he was enormously curious. In his military career he was sometimes called "Dick the Ruffian" and his disrespect for authority and convention earned him many enemies and a reputation as a scoundrel in some quarters. There were a number of rumors about him that meant he wouldn't exactly be welcome in a Victorian house.

For one thing, in a society where sexual repression was the norm, Burton's writings were unusually open and candid about his interest in sex and sexuality. His travel accounts are often full of details about the sexual lives of the inhabitants of the places he passed through, and many of those details must have been shocking to the average Victorian to say the least. Burton's interest in sexuality led him to make measurements of the length of the penises of the inhabitants of various regions which he included in his travel books. He also described sexual techniques common to the places he visited (offering hints that he had participated) and thereby breaking the racial and sexual taboos of his time. Naturally, many people considered the Kama Sutra Society and the books it published to be scandalous.

Timeline

Selected Works

- Goa and the Blue Mountains (1851)

- Scinde or the Unhappy Valley (1851)

- Sindh and the Races That Inhabit the Valley of the Indus (1851)

- Falconry in the Valley of the Indus (1852)

- Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah (1855) (My pilgrimage to Medina and La Meca [three vols.] Translation by Alberto Cardín. Barcelona, Ed. Laertes)

- First Footsteps in East Africa (1856) (First steps in East Africa. Expedition to the forbidden city of Harar. Barcelona, Ed. Laertes, 2009)

- Falconry in the Valley of the Indus (1857)

- The Lake Regions of Central Equatorial Africa (1859)

- The Lake Regions of Central Africa (1860)

- The City of the Saints, Among the Mormons and Across the Rocky Mountains to California (1861) (Travel to the city of the saints (the country of the Mormons). Barcelona, Ed. Laertes, 1986)

- Wanderings in West Africa (1863) (Vagrants in West Africa [three vols.] Editorial Laertes. Barcelona, 1999, 1999, 2000)

- Abeokuta and the Cameroon Mountains (1863)

- A Mission to Gelele, King of Dahomé (1864)

- Wit and Wisdom From West Africa; or, A Book of Proverbial Philosophy, Idioms, Enigmas, and Laconisms. Compiled by Richard F. Burton... (1865)

- The Guide-book. A Pictorial Pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. Including some of the More Remarkable Incidents in the Life of Mohammed, the Arab Lawgiver... (1865)

- The Highlands of Brazil (1869)

- Vikram and the Vampire, or Tales of Hindu Devilry. Adapted by Richard F. Burton... (1870)

- Letters From the Battlefields of Paraguay (1870)

- Unexplored Syria, Visits to the Libanus, The Tulúl el Safá, The Anti-Libanus, The Northern Libanus, and te 'Aláh (1871)

- Zanzibar; City, Island and Coast (1872), 2 vols.

- The Captivity of Hans Stade of Hesse, in A. D. 1547-1555, among the Wild Tribes of Eatern Brazil. Translated by Albert Tootal... and Annotated by Richard F. Burton (1874)

- Last Thule; or A Summer in Iceland (1875)

- Two Trips to Gorilla Land and the Cataracts of the Congo (1876)

- Etruscan Bologna; A Study (1876)

- Sind Revisited: With Notices of the Anglo-Indian Army; Railroads; Past, Present, and Future, etc. (1877)

- The gold Mines of Midian and The Ruined Midianite Cities. A Forthight's Tour in Northwestern Arabia (1878)

- The Land of Midian (1879)

- The Kasidah of Haji Abdu El-Yezdi (1880)

- Os Lusiads: Españoled by Richard Francis Burton: (Edited by His Wife, Isabel Burton) (1880), 2 vols.

- Camoens: His Life and His Lusiads. A Commentary... (1881), 2 vols.

- To the Gold Coast for Gold (1883)

- The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana (with F. F. Arbuthnot, 1883)

- The Book of the Sword (1884)

- The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (ten volumes, 1885)

- The Perfumed Garden of the Shaykh Nefzawi'' (1886)

- Iracema. The Honey-lips... by José de Alencar. Translated by Isabel Burton (1886)

- A Chronicle of the Seventeenth Century, by João Manuel Pereira da Silva, translated by Richard Francis and Isabel Burton (1886)

- The Supplemental Nights to the Thousand Nights and a Night (six volumes, 1886-1888)

- The Beharistan (Abode of Spring) By Jami. A literal translation from the Persian (1887)

- The Gulistan Rose or Rose Garden of Sa'di. Faithfully translated into English (1888)

- Marocco and the Moors: Being an Account of Travels, with a General Description of the Country and its PeopleBy Arthur Leared. Second edition revised and edited by Richard Francis Burton (1891)

- The Carmina of Gaius Valerius Catullus, Now first Completely Englished into Verse and Prose, the Metrical Part by Captain Richard F. Burton... and the Prose Portion, Introduction, and Notes Explanatory and Illustrative by Leonard C. Smithers (1894)

- The Jew, the Gypsy and El Islam (1898)

- Wanderings in Three Continents (1901)

- The Sentiment of the Sword: A Country-House Dialogue (1911)

- Trad. Priapeia or the Sportive Epigrams of divers Poets on Priapus: the Latin Text now for the first time Englished in Verse and Prose... (1890). Burton is responsible for translations in verse; the rest appears to be the work of his collaborator Leonard Smithers.

Burton Bibliography

There have been quite a few biographies of Burton. The list that follows is of biographies or books inspired by Burton, especially the most recent and influential ones.

- RUBIOMercedes. Burton's papers. The Secrets of the Triple Alliance War. Buenos Aires: Imago Mundi, 2012

- LOVELLMary S. A Rage to Live: A Biography of Richard & Isabel Burton. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1998

- ONDAATJEChristopher. Journey to the Source of the Nile. Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers Ltd., 1998

- ONDAATJEChristopher. Sindh Revisited: A Journey in the Footsteps of Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton. Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers Ltd., 1996

- McLYNNFrank. Burton: Snow on the Desert[s.l.]: John Murray Publishing, 1993

- McLYNNFrank. Of No Country: An An Anthology of Richard Burton. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1990

- RICEEdward.Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton: The Secret Agent Who Made the Pilgrimage to Mecca, Discovered the Kama Sutra, and Brought the Arabian Nights to the West. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1990 (in Spanish: Ed. Siruela, 1992)

- HARRISONWilliam. Burton and Speke[s.l.]: St Martins/Marek & W.H. Allen, 1984

- BRODIEFawn M. The Devil Drives: A Life of Sir Richard Burton. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1967

- FARWELLByron. Burton: A Biography of Sir Richard Francis Burton. London: Penguin Books, 1963

- EDWARDESAllen. Death Rides to Camel. New York: The Julian Press, Inc., 1963

- WRIGHTThomas.The Life of Sir Richard Burton, [s.l.]:[s.n.], 1905

- BURTONIsabel. The Life of Captain Sir Richard F. Burton KCMG, FRGS. [s.l.]: Chapman and Hall, 1893

- TROJANOWIlija. Der Weltensammler[s.l.]: Carl Hanser Verlag München Wien, 2006 (in Spanish: The Collector of WorldsTusquets Editors, 2008). The world collector. Tusquets Editors. 2008

Fictional character

- FARMER, Philip José: To your scattered bodies (Hugo Award 1972)

- FARMERPhilip José: The fabulous river boat

- FARMERPhilip José: The dark design

- FARMERPhilip José: The Magic Maze

- FARMERPhilip José: Gods of the World of the River.

Contenido relacionado

Dudley Moore

Theresa Wright

William H Macy