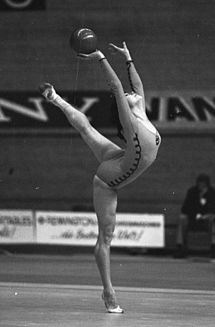

Rhythmic gymnastics

Rhythmic gymnastics is a form of gymnastics and a sports discipline practiced mainly by women, although it is currently also practiced by men. This discipline combines elements of ballet, gymnastics and dance, as well as use of various devices such as the rope, the hoop, the ball, the clubs and the tape. The exercises are carried out on a tapestry and with music.

In this sport, both competitions and exhibitions are held in which the gymnast is accompanied by music to maintain a rhythm in her movements, performing a montage with or without apparatus. Rhythmic gymnastics develops harmony, grace and beauty through creative movements, translated into personal expressions through the musical, theatrical and technical combination, which mainly transmits aesthetic satisfaction to the spectators. Practiced mainly by women, in recent years the number of male practitioners has increased. The tests are carried out on a mat and the duration of the exercises is approximately 90 seconds in the individual modality and 150 in the group modality. Like other disciplines of gymnastics, it has its roots in the studies of Rousseau, transforming over the years always linked to dance and musicality, until the 1930s, when it began to be practiced in the Soviet Union. as a sport and the devices we know today begin to be introduced in Germany.

It is governed by the International Gymnastics Federation (FIG), which develops the Code of Points and regulates all aspects of elite international competition. The most prominent competitions are the Olympic Games, the Rhythmic Gymnastics World Championships, the Rhythmic Gymnastics European Championships and the Rhythmic Gymnastics World Cup.

History of rhythmic gymnastics

Background

Rhythmic gymnastics has its historical background in gymnastic movements and systems that emerged in the 18th century throughout Western Europe.. The ideological origin of rhythmic is found in gymnastics based on rhythm, in ballet and in the so-called natural gymnastics. If in the ballet it is necessary to highlight the contributions of Jean-Georges Noverre, with respect to natural gymnastics it must be said that it takes its starting point in the theories of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) regarding the global development of the child, that included bodily aspects, hitherto not considered in educational theories.

The German pedagogue Johann Bernhard Basedow (1723-1790) would translate Rousseau's ideas into reality, making physical exercises an essential part of a harmonious and comprehensive education. Towards the end of the XVIII century, pedagogues such as Christian Gotthilf Salzmann, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi or Guts Muths would continue the naturalist ideas of Rousseau. The latter, considered the father of pedagogical gymnastics, wrote the first in-depth writings on the purpose of gymnastics, indicating that the exercises performed should be pleasant, in addition to developing the person completely. However, the arrival of the nationalist gymnastics of Friedrich Jahn would end up drowning out the pedagogical ideas of Guts Muths in Germany. These, however, would have a greater reception and continuation in the Nordic countries, especially in Sweden.

The Swedish doctor Pehr Henrik Ling, initiator of the so-called Northern Movement, further developed Rousseau's ideas, creating the so-called Swedish gymnastics around 1814. They were rigid exercises with little room for creativity and expression artistic, but which contributed fundamental and pedagogical principles to physical activity, absent in those years. The classification of the exercises into pedagogical, military, therapeutic and aesthetic is due to him, although Ling did not cultivate the latter, considering that they should be developed by other educators. In the aesthetic gymnastics promoted by Ling, students express their feelings and emotions through body movement. This idea was extended by Catharine Beecher, who founded the Western Female Institute in Ohio, USA, in 1837. In Beecher's gymnastics program, called grace without dancing, young girls worked out to the rhythm of music, going from simple calisthenics to more intense activities. Around 1864, the American teacher Diocletian Lewis (Dio Lewis) goes further than Beecher, including in her classes for girls hand-eye coordination exercises and the use of wooden rings, light weights, and Indian maces.

In the middle of the XIX century, with the French musician and professor François Delsarte, components more closely related to the subsequent rhythmic gymnastics, being the first to implement his ideas regarding the expression of feelings through body movements. More than a method of gymnastics, it tried to help the actors find natural postures and more expressive gestures. This new way of understanding movement was brought to the United States by Genevieve Stebbins, who opened a school of expression in New York and published the book The Delsarte System of Expression in 1885, which popularized the method. Based on Delsarte's ideas and Ling's exercises, Stebbins created a personal method in which the body should be an instrument capable of expressing itself artistically. Although his ideology was not able to take root in the American mentality, the work of his students did have a significant influence in Europe on the development of modern women's gymnastics and dance. Delsarte's work is considered the main inspiration for the Center Movement, a current in which the process of creating modern gymnastics was framed.

Movement of the Center: towards modern gymnastics

Of all the currents developed parallel to the Lingian movement in northern Europe (Movement of the North), the so-called Movement of the Center, developed in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, was the one that had the greatest relevance in rhythmic gymnastics. Born at the end of the 19th century, it developed in the XX. Considered an artistic-rhythmic-pedagogical manifestation, it was influenced by Rousseau's natural and globalist theories and Delsarte's ideas regarding expression, as well as by Ling's own Swedish gymnastics. This movement gave rise to Dalcroze's eurythmy and, later, Bode's modern gymnastics.

Starting in the 1890s, the Swiss educator and musician Émile Jaques-Dalcroze developed a method of musical education that he named eurhythmics (eurythmy), where the practice of rhythmic exercises was a means of to develop musical sensitivity through body movements. He also developed studies from which he obtained as a result the harmonic relationship of movements with balance and the states of the central nervous system, which generated a great influence in the formation of dance schools and in physical education, since it gained a new aspect and a new branch. Some of the teachers that he trained would later be the initiators of rhythmic gymnastics.

At the same time as Dalcroze, an American dancer, Isadora Duncan, also contributed to the rhythmic creation process. Considered a dance revolutionary and a promoter of free dance, she maintained that gymnastics was the basis of all physical education and developed gymnastics exercises based on naturalness, where turns, jumps and undulations of the body were a fundamental part. Her theories were the root of German expressionism in the field of dance, of which the Hungarian choreographer Rudolf Laban is one of the greatest exponents through the development, for example, of expressive dance. Laban developed innovative dance techniques far from classical ballet, trying to find more emotionally expressive movements, sometimes even going so far as to dispense with musical accompaniment, since in his opinion movement was the foundation of dance. The German dancer Mary Wigman, a disciple of Laban, was the other great exponent of expressionist dance, adapting many techniques from Isadora Duncan, such as the use of gymnastics and acrobatics.

It was with Rudolf Bode, a German music teacher who was a student of Dalcroze, that modern gymnastics definitively emerged. He began his work at the Dameros Institute, where Heinrich Medau and Mary Wigman also studied. Based on various influences such as Pestalozzi, Noverre, Delsarte, Dalcroze (eurythmy), Duncan (natural dance), or Laban and Wigman (expressionist dance), Rudolf Bode creates modern gymnastics (initially called expressive gymnastics), the first rhythmic gymnastics. In 1911 Bode founded his school in Munich and in 1922 his book Expressive Gymnastics was published and the Bode League was created, a kind of association to spread this new modality. Bode can therefore be considered the father of rhythmic gymnastics. His ideas spread rapidly throughout Europe, mainly in Germany, where they broke with a century of certain immobility in this regard, as the nationalist gymnastics of Friedrich Jahn continued to prevail in this country. (the first artistic gymnastics). From the very beginning, Bode's modern gymnastics was designed exclusively for women. As devices, Bode would introduce the cane, balls, medicine balls, the tambourine or the tambourine.

Bode's great successor in the development of modern gymnastics was Heinrich Medau, also a German, who in 1929 created the Movement College in Berlin. His most important contribution to gymnastics systems was the creation of a method directly focused on adult and young women, in which health was benefited, a correct attitude was developed, and the harmony of movement was exalted managing the whole body. Regarding the apparatus, he uses the same as Bode (with greater use of the ball) and introduces the hoop and clubs, which survive today. For Medau, the devices facilitated mastery of movement, directed the student's attention to the exercise she was performing, removed psychic inhibitions, managed to subdue shyness, and achieved a more rhythmic and fluid execution using the entire body. Medau also stressed the importance of correct posture and breathing in making movements. Medau's ideas in relation to technical and methodological principles follow a similar line to those of Bode, although he contributes his own that complete or replace them, especially with regard to musical improvisation, oscillating and undulating movements, and the use of rhythmic blows and claps. His theories and his movement systems were unveiled at the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

Outside Germany, neo-Swedish gymnastics, integrated into the Northern Movement, in which Elli Björksten (Finnish), Elin Falk and Maja Carlquist (Swedish) stand out in the process of creating rhythmic gymnastics. It arises as a way to make the lingian system (Swedish gymnastics) evolve, contributing with new components to eliminate its rigidity. They contributed the use of music and gave greater importance to the aesthetic aspect of the exercises and the naturalness of the movement, in addition to using a more flexible and adaptable concept of discipline. Like Medau, they used rhythmic blows and claps as technical resources and introduced ball rolling, swinging and hesitating in the execution of the exercises. To them is due in part the work of free hands and devices, mainly in the modality of groups. The demonstrations of the Maja Carlquist girls' team in the framework of the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games and the World Congress of Physical Education are relevant.

Establishment stage of the first regulations (1934 - 1977)

First approaches

Modern gymnastics, being practiced by groups of women, had already developed in the 1928 Amsterdam Olympic Games (the first Games with women's gymnastics competition), in the World Gymnastics Championships of 1934 (first World Gymnastics Championship with female participation), the 1950 World Gymnastics Championship, the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games, the first edition of the Gymnaestrada in Rotterdam (1953), or the Olympic Games of Melbourne 1956, however, it was developed as one more competition within classical gymnastics by apparatus (current artistic gymnastics), since in addition to the corresponding tests, a combined group exercise test was carried out where portable devices such as balls were used, clubs, hoop, etc. The work with balls of the Swedish team in the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games is noteworthy in this competition, which set them apart from the rest of the participants due to the use of harmonious movements in which the whole body acted and helped them hang the gold medal in combined group exercises. This test disappeared from the Olympic program in 1960.

The first time that rhythmic gymnastics appeared as a competitive sport was in the Soviet Union in the 1940s. Already in 1934, the center «Study of plastic movement» had begun the preparation of highly qualified Physical Education teachers in the Moscow and Leningrad (present-day St. Petersburg) Higher Institutes of Physical Culture. These, from their respective university chairs of «Artistic Movement», laid the foundations for the development of rhythmic gymnastics. In 1945 the National Committee for Physical Culture and Sports Affairs, attached to the Council of Ministers, held a conference where it announced the decision to develop a sports-oriented women's gymnastics in the Soviet Union, which then received the name artistic gymnastics (not to be confused with current artistic gymnastics), rhythmic gymnastics. Somewhat later, on October 22, 1946, this new sport modality was officially recognized in the country. This development as a sport materialized in the first exhibition championships organized in Tallinn (1947) and in Tbilisi (1948), until the 1st was held in 1949.er National Championship. Therefore, this country can be considered the cradle of current rhythmic gymnastics, being the first to organize both competitions and exhibitions.

It is worth highlighting the Soviet Shisch Kareva from this period, who wrote a pioneering book in this new sport in which he developed the apparatus and fundamental principles of it. This work had a fundamental influence on rhythmic gymnastics in Bulgaria, where its own current arose from 1951, the Bulgarian school, which in turn contributed to the enrichment of later rhythmic gymnastics. Already then the differentiating lines of the two main rhythmic schools began to be drawn. On the one hand, the Russian school based rhythmic gymnastics on classical dance and on basic body technique, and endowed the movements with expressiveness, harmony, elegance and spaciousness, but initially there was not a great presence of exercise risk. The Bulgarian school, for its part, although it took the Russian one as its starting point, was outlined due to the need to contribute new ideas to the little information they had, since then (1950s), there were no tournaments. or meetings at an international level that would help a clear sharing on the development that this sport should follow. At the Bulgarian national championships, originality and risk were mainly valued. From then on, a style characterized by a great diversity of elements and greater dynamism began to develop, as well as a high degree of the personal idiosyncrasy of the gymnasts, without neglecting technical correction. In 1961 the first meeting between the teams of the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria was held in Bulgaria. In the meeting it was possible to appreciate both styles as clearly different and the results left Bulgarian and Soviet gymnasts tied in the first positions. The Russian and Bulgarian schools of rhythmic gymnastics are still maintained today as differentiated styles and following a similar line in many aspects to that of their beginnings.

In June 1962, the International Gymnastics Federation (FIG) recognized rhythmic gymnastics (under the name modern gymnastics) as an independent sport at its 41st .er Congress in Prague.

First official international competitions

In December 1963, the first World Championship of Rhythmic Gymnastics, then still called modern gymnastics, was held, the World Championships in Budapest. In it, an individual contest was held with one floor exercise and two on the apparatus. In the absence of common guidelines, a wide range of techniques and styles could be appreciated. The first champion was the Soviet Ludmila Savinkova, followed by her compatriot Tatiana Kravtchenko and the Bulgarian Julia Traslieva. The FIG decided from then on to hold a World Cup every two years. In 1965 the World Championship in Prague took place. Three months before its celebration and with the aim of unifying criteria worldwide, an international course for judges was held in the same city. This fact contributed decisively to the foundations of the discipline today, agreeing that rhythmic gymnastics is not any type of dance nor can it be considered as part of artistic gymnastics, since it has its own style based on natural movements of the body. and in the personal expression of the gymnast. In this appointment, they competed with a mandatory free hands exercise (to help outline the orientation of rhythmic gymnastics) and three free exercises with ropes, ball and free hands. Notes divided into two sections (composition and execution) were awarded for the first time. In Prague, the then Czechoslovakia was elevated as a world power, obtaining gold and bronze overall with Hana Micechová and Hana Machatová respectively, leaving the Soviet Tatiana Kravtchenko with the silver medal.

In 1967, the World Championship in Copenhagen was organized, the third World Cup edition, which included the incorporation of a team competition for the first time. The victory in this new modality was for the Soviet group, which had Ludmila Savinkova among its ranks, thus becoming the only gymnast to be the world champion of the general competition as individual and in groups. As a result of this championship, the FIG created a special commission within the Women's Technical Committee which, from 1968 to 1972, was in charge of developing the regulations for the competitions, the rules for judging the exercises, the difficulties and specific techniques for the exercises. of ball, hoop and rope, or the penalties. In 1969, the Varna World Championship was held, the last World Championship to feature hands-free competition. Bulgaria obtained the gold and silver individually with the figures Maria Gigova and Nechka Robeva and the gold as a whole, starting then a close competition with the Soviet Union that would continue in future championships. After this championship, some rules were agreed to judge the exercises and a list of difficulties that resulted, in 1970, in the first Rhythmic Gymnastics Code of Punctuation. In 1971, the World Championships in Havana took place, the first held outside of Europe and the first in which the tape appeared as a mandatory exercise. Other free ball, hoop and rope exercises were also presented. Bulgaria continued with its hegemony by being gold in both modalities ahead of the USSR. In 1972, a new commission within the FIG, different from the one that had functioned until now and with greater autonomy, changed the name of the sport, from being called modern gymnastics to being called rhythmic gymnastics. modern. That same year the FIG asked the IOC for rhythmic gymnastics to be considered an Olympic discipline, but this request was rejected.

In 1973 the Rotterdam World Championship was organized. Clubs are included for the first time as a compulsory exercise, also performing the three free exercises with the ball, hoop and ribbon. In sets, the exercises were rope. Bulgaria repeated the success in the individual modality with its star gymnast Maria Gigova, who became in this championship the first gymnast to be world champion in the all-around three times (her record would later be equaled by Maria Petrova, Yevgéniya Kanáyeva and Yana Kudryavtseva, and would later be surpassed by Dina Averina). In 1975, the FIG commission charged with establishing modern rhythmic gymnastics became an autonomous Technical Committee. This new Committee once again changed the name of the discipline to sports rhythmic gymnastics (G.R.D.). That same year the World Championship in Madrid was held, in which there was a boycott from some Eastern countries. In this championship the obligatory exercise disappeared, since its purpose was to establish a clear and defined style for rhythmic gymnastics, which was considered to have already been achieved. The competition was developed with four free individual exercises with hoop, ball, clubs and ribbon and a group exercise with 3 balls and 3 ropes.

Expansion stage (1978 - 1983)

By this time, rhythmic gymnastics had already acquired much more solid foundations at the level of regulations, technique and organization, which allowed the development of subsequent championships with a much more stable character.

On March 16, 1978, part of the Bulgarian rhythmic gymnastics team lost their lives in a plane crash on a flight from Sofia to Poland. Among others, Julieta Shismanova (highest representative of the Bulgarian Federation and coach of gymnasts such as Maria Gigova and Nechka Robeva), coach Rumiana Stefanova and gymnasts Albena Petrova and Valentina Kirilova died in the tragedy. That same year the first Championship was held. Rhythmic Gymnastics European Championship in Madrid, where in the general competition the Soviet Galima Shugurova and Irina Deriugina won gold and silver, and the bronze went to the Spanish Susana Mendizábal.

In the 1980s there was an increase in the number of participants in both national and international competitions, as well as in the number of participating countries. In addition, a compendium of technical and organizational regulations regarding the championships held by the FIG was published. In 1980, the existence of three individual gymnasts per country in the European Championships was approved, a decision that was applied from 1982, which made the competition last one more day. Also at this time, the structure of the Code of Points was substantially innovated, taking the form of a classifier, which later allowed partial changes to be made without modifying the rest. In addition, the creation of the World Cup was discussed at the time.

In 1981, the IOC finally approved rhythmic gymnastics as part of the Olympic Games program from Los Angeles 1984, although only in its individual modality. A new system in apparatus rotation for FIG competitions was started in 1982, beginning a new two-year cycle from 1983 that could be repeated regularly. In 1983 the first Rhythmic Gymnastics World Cup took place, held in Belgrade, to which only the 20 best gymnasts classified in the World Championship prior to its celebration would have access. It is also worth noting the dominance that Bulgaria had in almost all the official championships in the 80s, especially in the World and European Championships, where it took the vast majority of available golds, being represented by figures such as Iliana Raeva, Anelia Ralenkova, Lilia Ignatova, Bianka Panova, Adriana Dunavska, Diliana Gueorguieva or Elizabet Koleva. This generation became known as the Golden Girls of Bulgaria.

Consolidation period (1984 - present)

In Los Angeles 1984 rhythmic gymnastics became an Olympic discipline, although only in individual mode. Due to the Cold War, the communist bloc, led by the Soviet Union, boycotted the Olympic Games being held in the United States. The first Olympic champion was Canadian Lori Fung, this being the only time an American rhythmic gymnast has won an international title. She was preceded by Doina Stăiculescu of Romania and West Germany's Regina Weber.

After the World Championships of Valladolid were held in 1985, the FIG Technical Committee transmitted to the recently created European Gymnastics Union (UEG) the competition of the European Championships and to the American Gymnastics Union that of the Championship of the Four continents. During 1986, the Technical Committee re-examined the new Code of Points in detail, modifying some aspects and experimenting with new ways of calculating the average and final grades based on the scores awarded between 1986 and 1987. The results served to shape the next Code, which He had to wait until 1988 when the Olympic regulations determined that the sports regulations could not be changed during the two years preceding the Games. Also this year there was an important modification in the group exercises, when it was agreed to perform them on different days of two exercises, instead of one. One composition would be carried out from this moment on with six identical apparatuses (this apparatus being the one that would not appear in the individual contest), while the other would be carried out with two different apparatuses (mixed exercise). This change was effective from the 1987 World Championship.

The media increased their interest in the retransmission of the tests at this time, which had a favorable impact on the economy of the different institutions dedicated to rhythmic gymnastics in the world. In 1991 the Spanish rhythmic gymnastics team was proclaimed world champion in the general competition, being the first time, not counting the boycott of the 1975 World Cup, that a country not belonging to the then-called Eastern Bloc achieved a world title.

In 1993 there was a major revamp of the Code of Punctuation. The admission of the group event in the Olympic program was accepted by the IOC in April of that year. Yuri Titov, president of the FIG, achieved this inclusion despite the fact that the IOC was reluctant to incorporate new disciplines and favored reducing the number of participants in the Games. This led to some organizational changes, including reducing the number of judges and individual gymnasts for the Atlanta 1996 Games, as well as the duration of the competition. Also, beginning in 1995, group exercises went from being performed by six gymnasts and one reserve to five gymnasts and one reserve.

In 1996 the modality of sets finally made its debut on the Olympic calendar at the Atlanta Olympic Games. The first Olympic title in this modality was obtained by the whole of Spain, followed by Bulgaria (silver) and Russia (bronze). The Spanish team, made up of Marta Baldó, Nuria Cabanillas, Estela Giménez, Lorena Guréndez, Tania Lamarca and Estíbaliz Martínez, received the pseudonym of the Golden Girls. In 1998 the FIG finally decided to change the name of the sport to gymnastics rhythmic sports to the current term, rhythmic gymnastics.

Currently the International Gymnastics Federation only recognizes the female modality. The men's category was developed in Japan around the 1970s, and the first Men's Rhythmic Gymnastics World Cup was held in that country in 2003 with the presence of five countries: Japan, Canada, South Korea, Malaysia and the United States. For the edition of 2005 Australia and Russia were added. In Europe, some federations such as the Spanish have also approved this modality, holding the first Spanish Championship in 2009, although with rules similar to women's rhythmic gymnastics, unlike those practiced in Asia.

The gymnast

Features and Preparation

The athletic career of a rhythmic gymnast is often short-lived compared to other sports. She normally starts practicing at an early age, entering junior age on January 1 of the 13th year, and senior age, and therefore eligible to compete in the Olympic Games, in the 16th year. The peak of form is usually in adolescence (15-19 years), although it is more common to see it from the twenties. The Spanish Almudena Cid and Carolina Rodríguez have played international competitions at the age of 28 and 30 respectively, being considered the longest-serving elite rhythmic gymnasts.

The body of a rhythmic gymnast is generally thinner and less defined than that of an artistic gymnast, who are usually shorter and stockier. Characterized by the high demand for coordination for the athlete, this modality has fundamental principles for good execution in symmetry and bilaterality. As in artistic gymnastics, due to its high technical difficulty and because the high level is reached at a early age, it is important to start training as soon as possible if you want to reach the elite, ideally starting between the ages of 2 and 6, since women have a development potential that can be maintained in the mature stage of basic motor skills, that is, between 15 and 20 years of age. The practice of rhythmic gymnastics must develop skills such as strength, power, flexibility, agility, dexterity and resistance, to reach the technical degree necessary to show vigor, beauty and harmony in the movements of the exercise. In general, rhythmic gymnastics has three aspects that must be worked on: body movement, handling of the apparatus and musical accompaniment. These three elements form the unit that is the foundation of rhythmic gymnastics.

As a preparation, the gymnast has physical exercises started at school age to improve her physical aptitudes and motor coordination, as well as encourage her social interaction, beyond the pleasure and stimulation coming from the practice. The introduction of the devices must be done gradually so that the girl adapts to the characteristics of each one. This preparation is carried out for the future, in which the gymnast will have an improvement in physical condition and will enjoy experiences arising from teamwork, as well as a greater psychological structure when having to face opposite situations such as victory and defeat.. Physical training can become harmful if it is poorly supervised and combined with a poor diet. A good nutritional education is essential for the maintenance of both physical and intellectual performance. That is why a study on each practitioner is usually needed in order to obtain personalized calorie consumption needs. If there must be restrictions in the diet, they are advised by nutritionists so that the gymnast does not harm her health. Various studies have confirmed that the regular practice of rhythmic gymnastics facilitates the development of the skeleton and prevents loss of bone mineral density associated with age.

In conclusion, for an ideal practice of rhythmic gymnastics, an interaction between gymnast, coach and family is necessary, in order to create adequate habits, both food and social and safety, for the maintenance of physical and psychological well-being, which will generate positive effects on the intellectual and sports performance of gymnasts.

Movements

The so-called body elements are the basis of individual and group exercises, and can be performed in different directions, planes, with or without displacement, supported on one or two feet or another part, and coordinated with movements of the entire body. body. There must be a harmony of them both with the rhythm and with the character of the music, as well as a relationship between those of each gymnast in group presentations, all taken into account by the judges. Among the main groups of body elements they find each other:

- Balance: It consists of reaching a flight situation. To be taken into account as difficulty you must possess features such as height, shape fixing during flight, good amplitude and be coordinated with a mastery of apparatus. Some guys are the ditch (or Grand jet), the cork, the Cossack, the carp, in circle, the arched, the butterfly or cabriole.

- Balance: The gymnast adopts a balance position for at least two seconds, usually standing on one leg and lifting the other. It can be done on medium tip (in relay), flat foot or on different parts of the body, always maintaining the fixing of the shape and coordinated with a masterpiece. Some examples are horizontal balance, Passé, the Grand écart, the Penché, the arabesquein circle or attitude.

- Giros: Also called rotations, they can be done on a half-point, flat foot, or another part of the body, always having a fixed and wide shape, and be coordinated with a masterpiece. Usually, at least there must be a 360o rotation. Some very common are on a leg with the free leg above the horizontal, with the free leg in horizontal, or with the free leg in Passé, can the last two form the fouettés when the force of the free leg is used as an impulse to rotate.

- Flexibility and waves: They can be performed with the support of one foot, two or any other part of the body, and it is required to fix the form and be coordinated with a masterpiece. In the 2013 - 2016 Score Code, they disappeared as a compulsory body difficulty group.

Equipment

Clothing

The clothing with which gymnasts compete has evolved over time, from the simple leotards used in the past, to the most complicated today, which in international gymnasts even have thousands of Swarovski crystals embedded. The jerseys must have some characteristics indicated by the corresponding federation. Both in female and male rhythmic, they must not be transparent and the neckline cannot exceed the lower line of the shoulder blades at the back and half of the sternum at the front, thin straps are not allowed. As for footwear, the gymnasts step on the mat with toecaps that are made of leather with two elastic straps to adjust them to the foot. They can be white or imitation leather. You have to wear collected, and if you compete together, normally all the members of it must wear it the same.

Gadgets

The FIG chooses which apparatus will be used in the exercises based on each category; only four of the five available fixtures are selected. In 2011, the rope was displaced in both modalities in the senior category. Depending on the categories, there are minimum measures for some devices, which in Spain are established by the RFEG:

| Benjamin Category | Ball: minimum of 15 cm in diameter. |

| Category alevín | Ring: minimum of 70 cm in diameter.

Mazes: minimum of 35 cm long. |

| Category children | Mazes: minimum of 35 cm long.

Ribbon: minimum 4.5 m long. |

| Junior, cadet and Youth Category | Ribbon: minimum 5 m long. |

The following are the five devices used in official rhythmic gymnastics competitions:

Rope

- Material: Hemp or any other synthetic material.

- Go!: According to the height of the gymnast; it is measured from the tip of the foot to the shoulders, folded by half.

- Let's go.: It has knots like mangos. The ends (not another part of the rope) can be wrapped in a length of 10 cm as decoration.

- Form: Everywhere the same diameter or narrower in the center.

- Implementation: The technical figures can be made with the string tense or loose, with one or both hands, and with or without changing hands. The relationship between the implemento and the gymnast is more intense than in other cases.

- Movements: Giros, hits, jumps, launch...

Every time the rope touches the ground it will be penalized. The possibility of the rope disappearing from the competition program is currently being discussed, since it is considered to be the device that has evolved the least in handling in recent years. However, it is still preserved in several categories, so its final demise is unclear.

Hoop

- Material: Plastic (must be of a rigid material).

- Diameter: 80 cm to 90 cm inside. The ring must reach the waist of the gymnast.

- Weight: At least 300 g.

- Form: It can be smooth or rough. It can be wrapped (total or partly) with a colour adhesive tape.

- Implementation: The ring defines a space. This space is used to the maximum by the gymnast, who moves within the formed circle. The execution of the hoop requires frequent changes of the movement, and the main requirement is the good coordination of the movements.

- Movements: Launching, displacement, rolling...

Ball

- Material: Goma or plastic.

- Diameter: 18 to 20 cm.

- Weight: At least 400 g.

- Implementation: The ball is the only implement in which gripping it strongly is not accepted. This means that a smoother and more delicate relationship between the body and the apparatus is required. Ball movements must go in perfect harmony with the body. The ball should not remain still on the ground, if not rolling, turning, etc.

- Movements: Rebounds, spins, figures in the form of 8, launches, reception with arms, legs, directed and undirected bearings, gigantic, retention, slides...

- Throwing: It is done with a succession of impulses that come from the legs, through a slight bending of the whole body to reach the tip of the fingers. The body and arms extend to the direction of the launch. The reception of the ball must be done without noise, buffering with an extension of arms to the ball, to end the movement following the line it carries, linking with another element or finishing the exercise. High-rise launches with control and precision in receptions are risk elements.

- Batte: To do this the hand must be attached to the shape of the ball, the wrist must be fixed, and the knees must accompany the movement with a bending and extension of legs. At the time of the boat we will accompany the ball with the hand until it comes out. The reception must be silent, following the line of the movement. There are boats on one and two hands, side or front.

- Bearings: Can be done on the floor or on the body of the gymnast (braces, trunk, legs). They start with an accompaniment of the arm and hand. During the tour, the ball must remain in contact with the bearing surface, and at the end it must be received with some part of the body.

- Rotations: Rotations can be performed on the floor or on the body of the gymnast, so that the ball spins around its axis after transmitting a boost with the hand. When the rotation ends, the ball must be brushed somewhere in the gymnast's body.

- Balances: The ball must be balanced softly and naturally with the relaxed hand, without taking it.

- Movements in eight: The ball is to move, as its name indicates, in the form of eight. The gymnast must have a relaxed hand and never take the ball. The breadth and fluidity of the movement are very necessary in this element.

- Circumductions: As in the previous two cases, the hand must be completely detached and inn on the ball. The movement this time has a circular shape. Both this element and the two mentioned above can be made to one or two hands.

Maces

- Material: Plastic, rubber or wood.

- Go!: 8 to 5 dm from one end to the other.

- Weight: At least 150 g per maza.

- Parties:

- Body: Protuberating part.

- Neck: Thin part.

- Head: Spherical part.

- Implementation: The gymnast uses the mazas to execute molinetes, turns, releases and as many asymmetric figures as possible, combining them with the many figures used in gymnastics without implementation. When the mosses are beaten, it should not be done with force. The mace exercises require a sense of highly developed rhythm, maximum psychomotor coordination and precision. The mosses are especially suited for ambidiest gymnasts.

- Movements: Launches with both or with one hand, mills, blows, retention, slip...

Ribbon

- Material: Satin or non-almidonated or similar material. It has a rod called styling, which can be made of wood, bamboo, plastic or fiberglass.

- Width: 4 cm to 6 cm.

- Go!: Up to 6 m.

- Weight: At least 35 g (without styling or union).

- Parties:

- Stylist: Rod holding the tape.

- Union: The tape is fixed to the rod by a flexible union made using a thread, a nylon string, or a series of articulated rings.

- Ribbon: It must be one piece.

- Implementation: The tape is long and bright, and can be released in all directions. Its function is to create designs in space. Your air flights create images and shapes of all kinds.

- Movements: Spirales, zigzag, gigantic, launch...

The end of the tape must always be in motion throughout the execution of the exercise, without inadvertently touching the ground.

Rules

Format

Can be practiced individually or in ensembles. The teams are currently made up of 5 gymnasts on the mat. They can all have the same apparatus or there can be 3 with the same apparatus and 2 with a different one (in this case the exercise is called mixed). Until 1994 there were 6 gymnasts. The range of duration of a group exercise goes from 2 minutes and 15 seconds to 2 minutes and 30 seconds, while individual exercises can be from 1 minute and 15 seconds to 1 minute and 30 seconds. The tapestry, also called practicable, has dimensions of 13 x 13 meters.

In the main FIG championships (Rhythmic Gymnastics World Championships, Rhythmic Gymnastics World Cup, Rhythmic Gymnastics European Championships and other continental championships) the competitions follow a set format. In individual modality, the qualification is usually held first (Competition I), where the notes of the 4 exercises of each gymnast are added to obtain those classified for the final of the general. Occasionally there is also a team contest (Competition IV) that does not mean a new competition, but arises from adding the 12 best scores from each country (3 per device) in the qualification. Subsequently, the apparatus finals (Competition III) take place, where the 8 best classified in each of the apparatus in the qualification compete. Finally, the final of the general competition (Competition II) takes place, where the 24 best gymnasts in the qualification have access. For its part, in group modality there is no qualification, but only two phases are held. The first is the general contest (Competition I), where the scores of the two exercises are added (the one with identical apparatus and the mixed one). The second is the apparatus finals (Competition III), where the 8 best-ranked teams participate in each of the general exercises. In the Olympic Games, only the general competition is held, both individually and in groups.

Although in the national rhythmic gymnastics teams there are usually only junior (13 - 15 years) and senior (over 16 years) categories, in federated rhythmic gymnastics at the national level more categories are developed depending on the age that is met the year the competition is held. In Spain these categories are youngest (8 - 9), juvenile (10 - 11), children (12 - 13), junior (14 - 15) and senior (16 years or more). Additionally, in the Individual Spanish Championship the 1st category is also present (where gymnasts who more than 2 years ago had belonged to the national team compete, first classified in this same category the previous year, and at least the first 3 classified the previous year in junior and senior category), the junior honor category and the senior honor category (where gymnasts belonging to the national team participate). With the exception of those of honor, these categories are also given in the Spanish Team Championship, although with greater flexibility regarding age.

Scoring system

In rhythmic gymnastics competitions the exercises are evaluated by the judges following the Code of Points, which is revised by the FIG every 4 years. In the current Code of Punctuation (2022 - 2024) the three-score model is used (difficulty + artistic + execution). Since 2013, the use of sung music in one of the exercises is also allowed, and since 2017 there is no limit maximum difficulty.

Traditional model (composition + performance)

In the 60s and 70s, the weight of the note fell mainly on the artistic part, with little presence of difficulties. In the 80s, more elements of difficulty arose, giving greater prominence to flexibility and risk in the launches, appearing new device originalities. Traditionally, until the year 2000, to obtain the final grade for an exercise, the composition and performance grades were added, each with a maximum value of 10 points in the modality of sets (20 in total) and 5 in individual mode (10 in total).

Three-score model (difficulty + artistic + execution)

At the end of the 90s there was an appearance of gymnasts whose exercises used flexibility as a main element (Russian Yana Batyrshina or Alina Kabáyeva for example), which was one of the motivations for a very important change in gymnastics. 2001 code, which doubled the number of required difficulty elements (although they would later be slightly lowered) and reduced the value of the artistic part. The final score for an exercise was then obtained by adding the scores for difficulty, artistic and execution, each with a maximum value of 10 points, so the final score would be at most 30 points. This score has undergone numerous modifications, such as in the 2005-2008 Olympic cycle, where the final grade would, however, be a maximum of 20 points by adding the average difficulty and artistic grade to the execution grade. Or, for example, in the Code of 2022 - 2024, since with the elimination of the maximum difficulty limit the overall grade could exceed 30 points.

Following the Code of the 2005 - 2008 Olympic cycle, we will describe each of the three notes. The difficulty grade would be based on the technical value of the assembly. This is divided into body difficulty and apparatus difficulty. The body difficulties were divided into four groups: jumps, flexibilities and waves, twists and balances. The mandatory use of each of them would depend on the device used. The apparatus difficulty note would take into account mastery with or without throwing, risk, pre-acrobatic elements and apparatus originalities. The artistic note would be based, as its name indicates, on the artistic value of the assembly. The use of music, the choreography used, the use of the entire mat, the variety of movements of the gymnast and the variety of use of the apparatus would be taken into account. Lastly, the execution note would value the correction in all the elements at a musical level, body technique and technique with the apparatus. His assessment would be based on a perfect model of realization of an element or movement. The errors with respect to the model are accumulated and added, subtracting at the end of the starting value.

Two-score model (difficulty + execution)

This model is followed by both the 2013 - 2016 and 2017 - 2021 Code of Punctuation, where the final grade for an exercise is obtained from the sum of the difficulty (D) and execution (E) grades, each one with a maximum value of 10 points, so the final score will be a maximum of 20 points (although in 2017 - 2021 the maximum difficulty limit is eliminated and the overall grade could therefore exceed 20 points). In addition, there are penalties, through which certain mistakes are penalized, subtracting points from the final grade.

- The note difficulty (equivalent to the traditional composition note) is composed of the sum of: body difficulty (salts, balances and rotations), combination of rhythmic steps, dynamic elements with rotation and launch (commonly known as risks) and the mastery of apparatus.

- The note implementation evaluates the correction in all elements at the musical, body and technical level with the apparatus. It distinguishes artistic faults and technical faults. In the former the unity of the composition, the music of the exercise, the expression of body or the variety in the use of space is valued; on the other hand, in the technical component aspects such as the technique of bodily movements, the basic technique of the apparatus, the equality of the work between the two hands during the exercise, etc. Errors with respect to the perfect model of realization are accumulated and added, at the end being reduced to the starting value (a 10 represents a perfect execution equal to the model to follow, without any error).

Regarding the penalties, it can be mentioned that:

- The apparatus must always be moving.

- The exercise must end at the exact moment when the music with which the execution was accompanied ends.

- The degree of difficulty must be presented in the apparatus, or in the movements of the gymnast, but it must always exist.

- Non-rhythmic steps within the tapestry are penalized.

- The exit of the tapestry, whether from the gymnast or the apparatus, is penalized.

- The attire of the unregulated gymnast is penalized.

- Communication with the trainer or with the companions during the execution of the exercise is penalized.

Dominant countries and teams

Soviet Union

Before its fragmentation, gymnasts from the USSR rivaled Bulgaria in sport. The first World Championship (Budapest 1963) was won by the Soviet Ludmila Savinkova, and the first team competition in a World Cup (Copenhagen 1967) was also won by the USSR. Other Soviet world champions were Elena Karpukhina, Liubov Sereda, Galima Shugorova, Galina Beloglazova, Irina Deriugina, Tatiana Druchinina, Marina Lóbach, Alexandra Timoshenko or Oksana Skaldina. Marina Lóbach was the first Soviet gymnast to be an Olympic champion at the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Unified Team was created, which appeared for the only time at the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games. Soviet/Ukrainian gymnasts Alexandra Timoshenko and Oksana Skaldina, who took gold and bronze.

Russia

After the fall of the USSR, Russia became the dominant country in world rhythmics at the beginning of the 1990s. Oksana Kóstina became Russia's first world champion as an independent country. At the 2000 Sydney Olympics, Yulia Barsukova was the first Russian to win Olympic gold. This was repeated at the 2004 Athens Olympics with gymnast Alina Kabáyeva. Yevgéniya Kanáyeva became the first individual gymnast in the discipline to win two gold medals at the Olympics, doing so in Beijing 2008 and London 2012. In addition, Yevgéniya is the most decorated rhythmic gymnast in history. Other notable gymnasts are Amina Zaripova, Natalia Lipkovskaya, Yana Batyrshina, Irina Cháshchina, Natalia Lavrova, Vera Sessina, Olga Kapranova, Daria Kondakova, Daria Dmítrieva, Margarita Mamún, Yana Kudryavtseva, Aleksandra Soldátova, Arina Averina or Dina Averina.

Ukraine

In the former USSR, a large number of gymnasts were of Ukrainian origin, including Ludmila Savinkova, the first world champion. Albina and Irina Deriugina—mother and daughter—played an important role in the success of rhythmic gymnastics in that country, training stars like Alexandra Timoshenko and Oksana Skaldina. After the fall of the USSR, Ukraine continued to achieve success with gymnasts like Ekaterina Serebrianskaya, Olympic champion in Atlanta '96. Other outstanding Ukrainian gymnasts were Elena Vitrichenko, Tamara Yerofeeva, Anna Bessonova, Natalia Godunko, Alina Maksymenko, Ganna Rizatdinova, Viktoria Mazur, Vlada Nikolchenko, Khrystyna Pohranychna or Viktoria Onoprienko.

Belarus

Belarus has been successful in both modalities even after the fall of the USSR. It should be noted that the first Soviet woman to be an Olympic champion was the Belarusian Marina Lóbach. Since the late 1990s, she has won several medals in the Olympic Games, winning two silver medals in individual mode (Yulia Raskina in Sydney 2000 and Inna Zhukova in Beijing 2008) and two bronze medals (Liubov Charkashyna in London 2012 and Alina Harnasko in Tokyo 2020), as well as two silver and one bronze in sets. Other notable gymnasts include Larissa Loukianenko, Olga Gontar, Melitina Staniouta, Aliaksandra Narkevich, Katsiaryna Halkina, and Anastasia Salos.

Bulgaria

Since the creation of rhythmic gymnastics, Bulgaria had a close competition with the USSR, especially in the first World Cups, where she was trained by Julieta Shismanova. The first big star in the Bulgarian ranks was Maria Gigova, the first gymnast to be three-time world champion in the all-around. In those years Julia Traslieva, Rumiana Stefanova, Nechka Robeva, Krasimira Filipova, Neshka Gueorguieva and Kristina Guiurova also stood out. The 1980s marked the peak of Bulgarian success with the generation of gymnasts called the Golden Girls of Bulgaria, which was made up of Iliana Raeva, Anelia Ralenkova, Lilia Ignatova, Bianka Panova, Adriana Dunavska, Diliana Gueorguieva or Elizabet Koleva, who they dominated almost all the World Cups and Europeans of those years. In the 1990s, Yulia Baycheva, Dimitrinka Todorova, Kristina Shekerova, Diana Popova, Mila Marinova, Stela Salapatiyska, Teodora Alexandrova and especially Maria Petrova, three-time world and European champion in the all-around, stood out. The 2000s saw a great decline in individual rhythmic gymnastics in Bulgaria, although gymnasts such as Elisabeth Paisieva, Simona Peycheva, Silvia Miteva, Boyanka Angelova, Mariya Mateva, Neviana Vladinova, Katrin Taseva and Boryana Kaleyn should be noted. At present Bulgaria stands out more in the modality of groups. The Bulgarian team achieved their first Olympic gold in Tokyo 2020, being the first time that a non-Russian team won the Olympic Games since Spain in Atlanta 1996. Bulgaria climbs back to the individual AA podium with Stiliana Nikolova winning the bronze in the World Championship 2022 in Sofia.

Spain

In individual modality, Spain achieved notable success with Carolina Pascual, silver medalist at the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games, Carmen Acedo, world champion in mace at the 1993 World Cup, Almudena Cid, gymnast who participated in four Olympic finals (1996, 2000, 2004 and 2008), and Carolina Rodríguez (gymnast), a Spanish gymnast with 12 national titles, achieved gold in the individual competition at the 2013 Mediterranean Games, as well as an Olympic medal in both groups (Athens 2004, where he obtained 7th place) and individually (London 2012, where he was 14th, and Rio 2016, where he was 8th). In the latter, she became the longest-serving rhythmic gymnast to compete in the Olympic Games, at the age of 30. Spain has historically been the most successful in the group modality, proclaiming itself world champion with the First Golden Girls in the general competition in Athens 1991, becoming the first Olympic champion of the modality in the Olympic Games. Atlanta 1996 with the team known as the Golden Girls, and obtaining the two-time world championship in maces (2013 and 2014) and Olympic silver in Rio 2016 with the group called the Equipaso.

Italy

Like Spain, Italy has achieved more success in the group modality. The Italian group has been four times world champion in the all-around competition and has won three medals (silver in Athens 2004, bronze in London 2012 and bronze in Tokyo 2020) at the Olympic Games. Although individually they have also achieved many victories in recent years, highlighting Julieta Cantaluppi, Veronica Bertolini, Alexandra Agiurgiuculese, Milena Baldassarri and Sofia Raffaeli in recent years, the first Italian individual world championship in 2022

Israeli

Israel has been one of the foremost countries in rhythmic gymnastics since the late 2000s. In 2000, gymnasts Irina Risenson and Neta Rivkin placed among the finalists for the first time at the Sydney Olympics. In 2020, Linoy Ashram, after proclaiming herself European champion in Kiev, won individual gold at the Tokyo Olympics, becoming the first Israeli gymnast and woman to win a gold medal at an Olympic Games, and the first non-Russian gymnast. to win an Olympic gold in this discipline since 1996 (after the Ukrainian Ekaterina Serebrianskaya in the Atlanta games of that year).

At the 2021 European Championships, Israel won two gold, two silver and two bronze medals. The rivalry between Ashram and the Russian Dina Averina, sharpened in the 2018-1019 World Cups and very pronounced in the Tokyo games, continued in this tournament, with the two alternating between first and second place in three of the individual modalities. Following Ashram's withdrawal after this championship, there was a reorganization of the Israeli team, which resulted in their non-participation in the 2021 World Cup in Tokyo. At the 2022 Europeans, Israel, now led by Daria Atamanov, returned to the podium with two gold medals (individual and group all-around), four silver and two bronze. At the World Cup that year in Bulgaria, with a clear Bulgarian and Italian domination (in the absence of Russian participation due to the conflict with Ukraine), Israel won two silver medals, both in sets (including the complete).

Rhythmic gymnastics in Spain

Rhythmic gymnastics is the fourth most practiced sports discipline among girls and adolescents in Spain, only surpassed by swimming, basketball and soccer, according to the Survey of Sports Habits of the School Population (2011), prepared by the CSD In addition, the national rhythmic gymnastics team is considered one of the most successful Spanish sports teams.

Although historically the dominators of this discipline have been participants from the former Soviet Union and gymnasts from Eastern Europe, Spanish gymnasts have achieved various successes since the creation in 1974 of the national rhythmic gymnastics team. The Spanish rhythmic had already had some forays at the international level, the first at the 1963 Rhythmic Gymnastics World Championship held in Budapest, and the second, 10 years later. In order to participate in the World Championship in Madrid in 1975 and in the European Championship in Madrid in 1978, the Spanish Gymnastics Federation created the first national rhythmic gymnastics team. The first national coach, the Bulgarian Ivanka Tchakarova, would take charge of her, and later, since 1979, the also Bulgarian Meglena Atanasova, who would be there until 1981. Her replacement would be the most important national coach to date, the Bulgarian Emilia Boneva, who was in the position of coach in three stages: the first, in the two modalities (individual and joint) from April 1982 to 1992; the second, solely as individual national selector for the 1993 World Championship; and the third, again in both modalities, from March 1994 to December 1996, when she was replaced by María Fernández. During that time, Boneva won a total of 63 medals in official international competitions as a coach.

The Spanish rhythmic gymnasts with the most medals in official international competitions (organized by the FIG, the UEG or the IOC) are Alejandra Quereda and Sandra Aguilar, with a total of 42. In World Championships, the most important competition in the FIG, those with the most medals are Estela Giménez, Marta Baldó, Bito Fuster and Lorea Elso, with a total of 8 each. Nuria Cabanillas has the most gold medals in this competition, with 3, although the last one was obtained as a substitute for the team in both years. This is the list of the Spanish rhythmic gymnasts who have been world champions the most times:

Medalero in World ChampionshipsThe Spanish rhythmic gymnasts who have only been proclaimed world champions once are Débora Alonso, Bito Fuster, Isabel Gómez, Lorea Elso, Montse Martín, Gemma Royo, Marta Aberturas, Cristina Chapuli, María Pardo, Sara Bayón, Marta Calamonte, Carolina Malchair, Beatriz Nogales and Paula Orive in ensembles, and Carmen Acedo as an individual.

The Spanish rhythmic gymnastics team has obtained a total of 146 medals in official international competitions (organized by the FIG, the UEG or the IOC). Of all of them, in the Olympic Games 1 gold and 2 silvers have been obtained; in World Championships, 7 golds, 11 silvers and 21 bronzes; in European Championships, 2 golds, 5 silvers and 17 bronzes; in Junior World Championships, 1 bronze; in Junior European Championships, 1 gold, 4 silver and 6 bronze; plus 2 silvers and 3 bronzes in World Cup Finals, 5 golds, 18 silvers and 29 bronzes in World Cup events, 1 gold, 2 silvers and 6 bronzes in European Cup Finals, 1 bronze in Championships of Europe by Teams and 1 gold in Pre-Olympics (updated to 18-9-2022).

At the national level, the most important competitions are the Individual Spanish Championship and the Spanish Team Championship. Carolina Rodríguez is the individual gymnast who has been champion of Spain in the general competition the most times counting all categories, with 12 titles (1 in juvenile, 1 in children, 1 in 1st category and 9 in honor category). Club Atlético Montemar and Club Ritmo are the most successful in the 1st category of teams. In addition, the Euskalgym is held annually in the Basque Country, an international gala where some of the best gymnasts in the world participate.

Milestones of Spanish rhythmic gymnastics

In 1975, María Jesús Alegre obtained the first medal for Spain in an international competition. She would be a bronze in the individual all-around at the World Championships in Madrid. It is also, up to now, the only medal achieved by a Spanish gymnast in an individual all-around competition at a Rhythmic Gymnastics World Championship.

In 1978, Susana Mendizábal achieved the first medal for Spain in a European Championship. She was a bronze in the individual general competition of the European Championship in Madrid. It is also, to date, the only medal won by a Spanish gymnast in an individual all-around competition at a European Rhythmic Gymnastics Championship.

In 1991, the Spanish team achieved the first gold medal for Spain in a Rhythmic Gymnastics World Championship. He was proclaimed world champion in the all-around in the group competition at the World Championships in Athens. The group was made up of Débora Alonso, Lorea Elso, Bito Fuster, Isabel Gómez, Montse Martín and Gemma Royo, as well as Marta Aberturas and Cristina Chapuli as substitutes. This generation would go on to be known as the First Golden Girls.

In 1992, Carolina Pascual achieved the first medal in the Olympic Games for Spanish rhythmic gymnastics. She would get the silver medal in the individual competition at the Barcelona Olympic Games.

In 1993, at the World Championships in Alicante, Carmen Acedo obtained what until now is the only individual gold medal achieved by Spain in a World Championships. She would get it in the mace competition.

In 1996, the Spanish team was proclaimed Olympic champion in the team competition at the Atlanta Olympic Games, in the first incursion of this modality in the Olympics. The team was made up of Marta Baldó, Nuria Cabanillas, Estela Giménez, Lorena Guréndez, Tania Lamarca and Estíbaliz Martínez. Upon their arrival in Spain, the media christened them the Golden Girls.

In 2008, Almudena Cid becomes the only rhythmic gymnast in the world who has managed to be in the final of four Olympic Games (1996 - 2008).

In 2013, Sara Bayón became the only Spanish gymnast to have been a world champion as an athlete and as a coach, being the world champion of 3 ribbons and 2 rings in Seville 1998, and as a coach, of 10 clubs in Kiev 2013 and Izmir 2014, directing the group called the Equipaso.

In 2016, the Spanish group known as Equipaso, achieved silver at the Rio Olympics, being the first Olympic medal for Spanish rhythmic gymnastics since 1996. The team was made up of Sandra Aguilar, Artemi Gavezou, Elena López, Lourdes Mohedano and Alejandra Quereda.

Controversies and topics in rhythmic gymnastics

For a long time, elite rhythmic gymnastics, like artistic gymnastics, has been affected by different controversies related to the demanding discipline or weight problems that some gymnasts have suffered (up to anorexia in very punctual), generally in Eastern European countries. In 1997 the FIG decided to raise the age to compete in the Olympic Games from 15, the limit set in 1981, to 16 years.

In Spain, after the 1996 Olympic Games, one of the gymnasts of the national team, María Pardo, accused the then coach Emilia Boneva of imposing harsh discipline, although the rest of the members defended the Bulgarian. A little over a year later, another gymnast of hers, the Olympic champion Tania Lamarca, was excluded from the national team for weighing 2.7 kilos more than the weight required by the coach María Fernández, as she recounts in her book Lágrimas por a medal. As Tania does in her book, her partner Nuria Cabanillas, during an appearance in the Senate at the "Special Commission on the situation of athletes at the end of their sports career" in 2001, showed her He disagreed with Fernández's decisions regarding the weight and denounced the situation of abandonment and defenselessness that the gymnasts of the group experienced after their withdrawal, not receiving any help or guidance from the Federation in their adaptation to the "real world" and also facing non-payments for part of this The testimonies of the gymnasts of the Spanish national team regarding the role of the Federation and the rest of the organizations after its withdrawal coincided in many aspects throughout the years:

"After giving them the best years of your life, no one in the Federation remembers you. When you leave it, the world falls apart and no one helps you. You are your only friend, teacher and director."

—Marta Bobo (retired in 1985), in statements to The Weekly Country

"They had always marked me the pattern to follow: today we compete here, travel there, train here. Instead, no one warned me that I would be alone later. Years of psychological training to be the best, the strongest, the champion and no half minute of advice to face the real world, to focus my studies, to look for a future profession. Not a single word of help or advice to face the day after."

—Tania Lamarca (retired in 1997), in her book Tears for a medal

"When I was a gymnast, I had the feeling that the people of the Federation used me as if it were a machine, but then, when that period ended, I felt that it was no longer at all, especially because I was giving everything I had and, at the end, I had absolutely nothing."

—Nuria Cabanillas (retired in 1999), in the “special commission on the situation of athletes at the end of their sports career”

The senator and also a former athlete Miriam Blasco, who was president of the commission, presented its conclusions to the Government in October 2004, and in December 2007 a reform of the law was approved that contemplated several of the measures requested by the Senate to try to correct this situation, which was relatively common among athletes from different disciplines. past:

"Everything has improved. They left aside the studies and when they left gymnastics it took them to return to normal life [...] they were isolated from the world, they only lived for gymnastics. We live in the Blume Residence, in the heart of Madrid. We live with athletes of all kinds who are in similar situations and have their moral support. In addition, we combine sports and studies. We have all the necessary resources to train and options for when we stop doing so."

—Alejandra Quereda, in statements in 2014 to Olympic Planet

As for doping, it is a relatively rare infraction in rhythmic gymnastics, although there have been cases due to the use of diuretics such as furosemide, a substance prohibited by WADA that is used to lose weight in a short time or to mask other substances. The positives for furosemide of the Russian gymnasts Alina Kabáyeva and Irina Cháshchina at the Goodwill Games in August 2001 are relevant, for which they were sanctioned for a year and dispossessed of the results achieved in subsequent months, including the Madrid World Cup medals. The Bulgarian Simona Peycheva was sanctioned for ten months without competing for the use in 2003 of that same substance. In 2002 the Ukrainian Anna Bessonova was sanctioned for two months for an ephedrine derivative, a decongestant substance that can be used as a masking agent.

Regarding the negative clichés that accompanied gymnastics for many years and the exaggeration of some controversies in the media, the former Spanish gymnast Susana Mendizábal, author of numerous studies and research on rhythmic gymnastics, stated the following in an interview in 2001 on the occasion of the publication of his book Fundamentals of rhythmic gymnastics: myths and realities:

"It is more desirable to relate gymnastics to anorexia because to reflect that those that we have been at a high level would repeat that experience no longer matter. Any other high-performance sport has its problems, like everything in life [...] The majority do this voluntarily knowing the hardness and sacrifice it entails, but also being aware of how positive gymnastics have."