Revolution of 1868

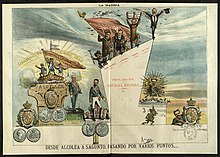

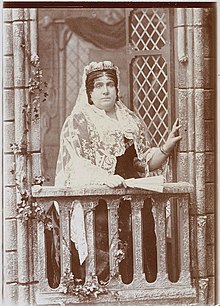

The Revolution of 1868, called the Glorious or September Revolution or la Septembrina, was an uprising military with civilian elements that took place in Spain in September 1868, which meant the dethronement and exile of Queen Elizabeth II and the beginning of the period called the Democratic Six-Year Period (1868-1874).

As the historian María Victoria López-Cordón pointed out, "the September Revolution was a sudden shock in the history of the Spanish 19th century, the effects of which were widely felt throughout the country's geography", since from The first attempt in its history to establish a democratic political regime took place in the country, first in the form of a parliamentary monarchy, during the reign of Amadeo I of Savoy (1871-1873), and later in the form of a republic, the First Republic. (1873-1874). However, both formulas ended up failing.

Background

In the mid-1860s, discontent against the monarchical regime of Isabel II was evident and the Spanish moderantismo, in power since 1844, except for the intervals of the progressive biennium (1854-1856) and the governments of the Liberal Union (1858-1863), was in a strong internal crisis. For its part, the Progressive Party, with Pedro Calvo Asensio as one of its promoters, had opted for withdrawal in the elections to delegitimize the Cortes that came out of them. In 1864 General Narváez returned to power, who had to abandon it after the tragic events of the Night of San Daniel, being replaced by General Leopoldo O'Donnell.

In June 1866 an insurrection took place in Madrid to put an end to the Monarchy of Isabel II that was dominated by the government of the Liberal Union of General O'Donnell and that was known as the uprising of the San Gil barracks, because it was the sergeants of this artillery barracks who led the uprising. The following month, Queen Elizabeth II dismissed General O'Donnell for considering that he had been too soft on the insurgents, despite the fact that 66 of them had been shot, and appointed General Narváez, leader of the Moderate Party, to replace him..

Narváez immediately adopted an authoritarian and repressive policy, which made it impossible to take power with O'Donnell's Unión Liberal, which then opted to create a "vacuum in the Palace" —according to O'Donnell's own expression. #39;Donnell—, which meant withdrawal in the Senate, but what the unionist leader flatly refused was to agree on any initiative with the progressives, with whom he was "hurt by the events at the San Gil barracks, especially with Prim”, leader of the Progressive Party and the coalition of forces that sought the overthrow of Isabel II. Only after O'Donnell's death, in November 1867, would the Liberal Union — then led by General Serrano — join the Ostend pact that progressives and democrats had signed a year earlier.

The economic crisis of 1866-1868

At the beginning of 1866 the first financial crisis in the history of Spanish capitalism broke out. Although it was preceded by the crisis in the Catalan textile industry, whose first symptoms appeared in 1862 as a result of the cotton shortage caused by the American Civil War, the trigger for the financial crisis of 1866 were the losses suffered by the railway companies, which dragged banks and credit companies with them. The first bankruptcies of credit companies linked to the railway companies occurred in 1864, but it was in May 1866 when the crisis reached two important credit companies in Barcelona, the Catalan General de Crédito and Crédito Mobiliario Barcelonés, which unleashed a wave of panic.

The financial crisis of 1866 was compounded by a serious subsistence crisis in 1867 and 1868 caused by poor harvests in those years. Those affected were not businessmen or politicians, as in the financial crisis, but the popular classes due to the scarcity and high cost of basic products such as bread. Popular riots broke out in various cities, such as in Seville, where wheat multiplied its price six times, or in Granada, to the cry of "bread for eight [reals]." The subsistence crisis was aggravated by the growth in unemployment caused by the economic crisis unleashed by the financial crisis, which affected above all two of the sectors that provided the most work, public works —including railways— and construction. The coincidence of both crises, the financial one and the subsistence one, created "explosive social conditions that gave arguments to the popular sectors to join the fight against the Elizabethan regime".

The Ostend Pact

The Pact of Ostend between progressives and democrats, which receives its name from the city in Belgium where it was signed on August 16, 1866, was an initiative of the progressive general Juan Prim with the aim of overthrowing the Monarchy of Elizabeth II. It consisted of two points:

1.o, destroy what exists in the high spheres of power;

2.o, appointment of a constituent assembly, under the direction of a provisional Government, which would decide the fate of the country, whose sovereignty was the law it represented, being elected by direct universal suffrage.

The ambiguous wording of the first point made it possible to incorporate other personalities and political forces into the Pact. Thus, after the death of O'Donnell, Prim and Serrano —paradoxically, the same soldier who had led the repression of the uprising at the San Gil barracks— signed an agreement in March 1868 whereby the Unión Liberal joined to the Pact. "With this, the Liberal Union accepted the entry into a new constituent process and the search for a new dynasty, and, according to the second point [of the Ostend pact], the sole sovereignty of the nation and universal suffrage."

Narváez's response was to accentuate his authoritarian politics. The Cortes closed in July 1866 did not reopen because they were dissolved and new elections were called for the beginning of 1867. The "moral influence" of the government gave such an overwhelming majority to the ministerial deputies that the Liberal Union, the closest thing to a parliamentary opposition, was reduced to four deputies. In addition, in the new regulations of the Cortes approved in June 1867, three months after they were opened, the vote of no confidence was suppressed, thus significantly reducing their ability to control the government. In April 1868 General Narváez died and the The queen appointed the ultra-conservative Luis González Bravo to replace him, who continued with the authoritarian and repressive policy of his predecessor.

Outbreak of the revolution

At the beginning of September 1868 everything was ready for the military pronouncement that it was agreed would begin in Cádiz with the uprising of the fleet by unionist admiral Juan Bautista Topete. General Prim arrived there on the night of September 16 from London, via Gibraltar, accompanied by the progressives Práxedes Mateo Sagasta and Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla, before the Unionist generals arrived from the Canary Islands on a steamer rented with money from the Duke of Montpensier. who were in exile there, led by General Francisco Serrano. Prim and Topete decided not to wait and on September 18 Topete revolted at the head of the squad. The next day, after the arrival of Serrano and the unionist generals from the Canary Islands, Topete read a manifesto written by the unionist writer Adelardo López de Ayala in which the pronouncement was justified and which ended with a cry — «Long live Spain with honor! »— who would become famous. According to Josep Fontana, the manifesto "was a true prodigy of political ambiguity".

Spanish: the city of Cadiz put into arms with all its province (...) denies its obedience to the government that resides in Madrid, sure that it is loyal interpreter of the citizens (...) and determined not to depose the weapons until the nation regains its sovereignty, manifests its will and is fulfilled. (...) The fundamental law (...), corrupted the suffrage by the threat and bribery, (...) the municipality died; pasture the Administration and the Treasury of immorality; tyranny the teaching; move the press (...). Such is Spain today. Spanish, who hates her so much that she does not dare to exclaim: "This is how it must always be?" We want a common legality for all created to have implicit and constant respect for all. (...) We want an interim Government representing all the living forces of the country to secure order, while universal suffrage lays the foundation for our social and political regeneration. We have to carry out our unshakable purpose with the contest of all the liberals, unanimous and compact in the face of the common danger; with the support of the settled classes, they will not want the fruit of their sweats to continue to enrich the endless series of agiothists and favorites; with the lovers of order, if they want to see what is established on the very foundations of morality and law; with the ardent support of freedom (...) Spanish: come all to the weapons, the only means of saving the blood flow (...), not with the impulse of the cone, always wicked, not with the fury of anger, but with the solemn and powerful serenity with which justice draws its sword. Long live Spain with honor!

«The manifesto "Spain with honor" drafted by Adelardo López de Ayala and signed by the Duke of la Torre, Juan Prim, Domingo Dulce, Ramón Nouvilas, Rafael Primo de Rivera, Antonio Caballero and Fernández de Rodas and Juan Bautista Topete was called to be one of the basic emblems of Spain liberal and democratic".

In the days that followed, the uprising spread throughout the rest of the country, starting with Andalusia. On September 20, the first board was formed in Seville that published a manifesto in which it exposed a series of popular demands, such as the abolition of the fifths and consumption or religious freedom, which went much further than what was offered in the manifesto. read by Topete. For his part, Prim aboard the armored frigate Zaragoza toured the Mediterranean coast, getting all the riverside cities from Malaga to Barcelona to join the movement.

The day before, September 19, González Bravo resigned and Queen Elizabeth II appointed General José Gutiérrez de la Concha to replace him, who kept almost all the ministers of the previous government and put González Bravo in charge of the Ministry of Governorate. General de la Concha organized an army in Madrid as best he could, given the lack of support he found among the military commanders —not a single general "appeared to me then, or even later, to ask me for a position to fight the revolution," he would affirm. later—and sent him to Andalusia under the command of General Manuel Pavía y Lacy, Marqués de Novaliches, to put an end to the rebellion. At the same time, he advised the queen to return to Madrid from San Sebastián, where she was on her summer vacation, like Father Claret who told him: "If your majesty were a doll, I would put it in my pocket and run to Madrid to save Spain from its revolution. However, shortly after starting the train trip to Madrid, General de la Concha sent a telegram to the queen asking her now to continue in San Sebastián because the situation of the loyal forces had worsened.

On September 28, the decisive battle of Alcolea (in the province of Córdoba) took place in which the victory went to the rebel forces under the command of General Serrano who had the support of thousands of armed volunteers. The following day the uprising triumphed in Madrid and on the 30th Isabel II left Spain from San Sebastián.

In the message addressed by the queen to the nation "by putting my plant in a foreign land" she warned that she was not renouncing

the integrity of my rights cannot in any way affect you the acts of the revolutionary government; and less you agree to the assemblies that will necessarily form the impulse of demagogic furors, with manifest coercion of consciences and wills.

Then all resistance from the forces loyal to the queen ended and on October 8 a provisional government was formed, headed by General Serrano, and of which General Prim and Admiral Topete were a part. Thus was sealed the triumph of what would be called the Revolution of 1868 or The Glorious that had put an end to the reign of Isabel II.

«As in 1840 and 1854, the scheme of the pronouncement appears with complete clarity: first, the resentment of the political-generals for their distance from power and the justification of this resentment in theoretical principles; later, the stage of the surveys and the commitments; finally, the pronouncement itself, accompanied by the emotional and vibrant proclamations, in which an appeal is made to the people and in which what is not wanted is better exposed than what is planned to be done ». However, that of 1868 presents some novelties: "the objective of the pronouncement is not directed only against a corrupt Government, but against the Queen herself, who is judged incompatible with "honesty and freedom" 3. 4; that the pronounced proclaim; their diffusion from the periphery, where they have their strength, is very rapid, imposing itself from the periphery to the center; and finally, the very nature of the commitment contracted by the conspirators was an unprecedented novelty: the fact that it was a Constituent Assembly, elected by direct universal suffrage, which decided the type of government that the country should have.

That a classic pronouncement became the «Glorious Revolution» of 1868, was due, according to María Victoria López Cordón, to the enthusiastic support given to it by the bourgeoisie, the «citizen classes» and in some cases the peasants. "It was this participation, together with the desire for change that the majority of the country was experiencing and the rapid collapse of official Spain, which produced the easy mirage of turning the Cádiz pronouncement into the Revolution of September 1868". Manuel Suárez Cortina points to this direction when he points out that what both the Liberal Union and the Progressive Party were looking for —the latter in a more radical sense— was to eliminate the obstacles that would make it possible to “culminate the transition towards a fully bourgeois society, where the capitalist system would function a rational way", while the Democratic Party did "seek a real change in living conditions and [was] the one that demanded, along with a true democracy based on universal suffrage, the liquidation of those measures that most affected the popular classes: fifths, consumption, a true adherence to Europe. The democratic revolution was the goal that mobilized those popular sectors that organized the barricades and supported with their attitude the revolutionary Juntas that the Provisional Government later took care of dismantling.

The historiographical debate on the causes of the revolution

Liberal historiography of the 19th century explained the 1868 revolution on political grounds. According to this vision, during the reign of Elizabeth II there was a confrontation between two ideologies: an almost absolutist, reactionary, clerical one, represented by the Moderate Party and by the Crown and its clique; and another liberal, reformist, anti-clerical (but not anti-Catholic) and progressive. Thus the revolution of 1868 meant the triumph of the second over the first, as demonstrated by the cry that resounded loudly during "La Gloriosa": "Long live National Sovereignty! Down with the Bourbons!"

In 1957, the Catalan historian Jaume Vicens Vives questioned whether political motives were sufficient to explain the revolution and argued that the difficult economic situation Spain was going through at that time had to be taken into account due to the financial crisis of 1866 which would explain why the "bourgeoisie" "separated" from the Elizabethan regime to overthrow the incompetent government of the Moderate Party and the throne of Elizabeth II itself, which was the one who supported it. This thesis was developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s —coinciding with the first centenary of the revolution— by a series of historians such as Nicolás Sánchez Albornoz, Manuel Tuñón de Lara, Gabriel Tortella and Josep Fontana. The latter published a book in 1973 in which the longest chapter of it was entitled «Economic change and political crisis. Reflections on the causes of the 1868 revolution» that would exert great influence and in which he pointed out that a good part of the politicians and soldiers who led the revolution had interests in the railway companies whose growing losses had triggered the financial crisis of 1866 -the General Serrano, for example, was the president of the Northern Railway Company, which was going through serious problems that only a State grant could solve. In addition, it was necessary to consider the importance of another crisis with economic roots, parallel to the financial crisis, the subsistence crisis of 1867-1868 as a result of the bad harvests of those years that caused a serious shortage and shortage of basic products such as bread and that It hit the popular classes hard. All these studies opened up a great debate, especially when Miguel Artola in those same years returned to defend the primacy of political factors over economic and social factors to explain the revolution.

In the year 2000 Gregorio de la Fuente published a study on the Revolution of 1868 in which he defended the thesis that "La Gloriosa" had occurred as a result of the conflict between two sectors of the political elites of the Elizabethan era: a "revolutionary" sector headed by the Progressive Party allied with the Democratic Party, and led by General Prim; and a conservative sector that supported Isabel II and that was initially made up of the Moderate Party led by General Narváez and the Liberal Union of General Leopoldo O'Donnell, and which failed in its attempt to reintegrate into the regime. to the progressives. Precisely the death of these two leaders (the first in April 1868 and the second in November of the previous year) was a decisive element in the fall of Elizabeth II, since with the death of the first the regime lost its main defensive bastion due to the influence he had in the Army and with the death of the latter the last obstacle that prevented the Liberal Union from going over to the "revolutionary" camp disappeared, which sealed the final fate of the monarchy of Isabel II.

In De la Fuente's study, the thesis of economic and social causality of the 1868 revolution elaborated in the 1970s was also criticized. Thus, De la Fuente pointed out that the financial crisis of 1866 had affected the entire political elite equally Elizabethan, so it did not explain why a sector of it remained on the side of Elizabeth II and another on the revolutionary side, and therefore the financial crisis had to be ruled out as one of the main causes of the revolution. In fact, it could be verified that the majority of businessmen, bankers and large merchants and businessmen neither collaborated nor joined the pronouncement. As for the subsistence crisis of 1867-1868, De la Fuente also ruled it out as a direct cause of the revolution, because the popular mobilization occurred after the revolution and as a consequence of the greater margin of freedom that it brought with it, and not before. However, Josep Fontana, in a book published in 2007, reaffirmed the importance of the economic causes of the 1868 revolution: above by politicians and the military who had limited objectives: to end the blockade of the parliamentary system that prevented progressives from gaining power and to implement emergency measures to resolve the poor economic situation, particularly that of the railway companies».

A synthesis of the relative consensus that has currently been reached in the debate on the causes of the 1868 revolution can be found in two books published in 2006 and 2007. In the second of them, Juan Francisco Fuentes summarizes as follows the state of the matter:

It is therefore necessary to rule out simplistic interpretations of the end of the Israeli Monarchy based on a causal-effect relationship between the economic crisis and the Revolution of 1868, in which so much protagonistism had some politicians and generals directly affected by the situation of the financial and railway companies. But we cannot ignore the importance that the great crisis of Spanish capitalism begun in 1864 had in the general perception of political and economic elites: the conviction that the island regime, finally reduced to a small political-clerical clique, had completely isolated itself from national reality. In the eyes of a good part of Spanish society, that was the end of an era. A serious subsistence crisis in the years 1867-1868 would have just spread that sense of national catastrophe that takes over the country at the last stage of the reign of Isabel II

Consequences

From the triumph of the revolution and for six years known as the Democratic Six-Year Period (1868-1874) an attempt was made to create a new system of government in Spain.

The coalition of liberals, moderates, and republicans faced the task of finding a better government to replace Elizabeth's. At first the Cortes rejected the concept of a republic for Spain, and Serrano was appointed regent while a suitable monarch was sought to lead the country. Previously, a liberal constitution had been approved and promulgated by the courts in 1869.

The search for a suitable King ultimately proved more than problematic for the Cortes. Juan Prim, the eternal rebel against the Elizabethan governments, was appointed leader of the government in 1869 and General Serrano would be regent, and his is the phrase: «Finding a democratic king in Europe is as difficult as finding an atheist in heaven! !». The option of appointing an elderly Espartero king was even considered, although he was rejected by the general himself, who, however, obtained eight votes in the final count.

Many proposed Isabel's young son, Alfonso (who would later become King Alfonso XII of Spain), but the suspicion that he could be easily influenced by his mother and that he could repeat the previous queen's failures made them not was a viable alternative. Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg, former regent of neighboring Portugal, was also considered a possibility. Another possibility was Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern, of the Hohenzollern House, who was proposed by Otto von Bismarck, and who openly provoked the rejection of France, to the point that the French foreign affairs minister sent the so-called Ems Telegram., which would later be the trigger (or the excuse) for the Franco-Prussian war. Finally, an Italian king, Amadeo of Savoy, was chosen, but his reign only lasted two years and a month between 1871 and 1873.