Republic of New Granada

Republic of New Granada was the name given to the unitary republic created by the central provinces of Gran Colombia after its dissolution in 1830. It maintained that name from 1831 to 1858, when it passed to be called the Grenadine Confederation. Its territory covered the current countries of Colombia, Panama and at its maximum extent, sovereignty over the Mosquito Coast, currently in Nicaragua, was disputed with the Federal Republic of Central America and the Kingdom of Great Britain.

History

After the dissolution of Gran Colombia, two new countries emerged from the territories that made up the northern and southern departments called the State of Venezuela and the State of Ecuador. The provinces that geographically occupied the central part of the disintegrated Gran Colombia, which at that time included the old departments of Boyacá, Cauca, Cundinamarca, Magdalena and Istmo, decided to form a new State. The era of the Republic of New Granada was characterized by political, social and economic changes, which caused disputes and confrontations between various social sectors.

Through the Apulo Agreement (carried out on April 28, 1831), General Rafael Urdaneta, last president of Gran Colombia, handed over command to Domingo Caycedo (May 3, 1831).

The Constitution of 1832

On October 20, 1831, a Grenadine Convention was held where the separation was approved and in which a centralized and presidential republic was temporarily called "State of New Granada" until the promulgation of a new constitution. On November 17, 1831, the Fundamental Law was promulgated, but work continued on it during 1832. Francisco de Paula Santander was appointed president by Congress for a period of four years, while the senators' term was reduced from eight. to four years and that of the representatives from four to two years. The departments were eliminated, leaving only the old provinces. Greater representation and power was granted to the provinces.

In this period the centralists and the ecclesiastics began to distinguish themselves with the name of conservatives and their opponents, the federalists, with the name of liberals.

On February 29, 1832, the National Convention, made up of the representatives of the provinces of Antioquia, Barbacoas, Bogotá, Cartagena, Mompós, Neiva, Pamplona, Panama, Pasto, Popayán, Socorro, Tunja, Vélez and Veraguas, sanctioned a new constitution through which the country was officially called "Republic of New Granada" as of March 1 of that year.

War of the Supremes

President José Ignacio de Márquez sanctioned a law in 1838 that suppressed Catholic convents that housed fewer than eight religious in order to use them as centers of public instruction, which caused several priests of the city of San Juan de Pasto revolted, even though this measure had the support of the archbishop of Bogotá.

The uprising was put down two months later, but it intensified when the regional leaders rose up against the central government in order to obtain political and economic demands (hence its name "war of the Supremes"). In July In 1840, José María Obando escaped from the prison where he was awaiting trial for the murder of Antonio José de Sucre in 1828 and began an uprising that was used by other anti-government leaders to generalize the civil war.

The war soon spread to other provinces and included a border conflict with the Republic of Ecuador, because the clergy of Pasto depended on it. At the moment that the Ecuadorian troops commanded by Juan José Flores crossed the border, these commanders revolted in their respective regions. However, this movement did not have a single leadership, which allowed its defeat in 1842.

The separation of Panama in 1840

The war of the Supremes motivated the Panamanian political leadership to remove the isthmus of Panama from the conflict and proclaim an independent and sovereign republic from the rest of the country. On November 18, 1840, with the leadership of General Tomás Herrera, the State of the Isthmus was established by Fundamental Law. The reincorporation of the Isthmus of Panama was conditional on the Government of New Granada adopting a federal political system that would satisfy the needs of the Isthmus people.

This independent country lasted thirteen months and some days; As soon as the New Granada government managed to defeat the belligerents, a military expedition was prepared in Cauca to invade the isthmus. General Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera sought to avoid the imminent conflict, sending Commander Julio Arboleda as commissioners, who was unsuccessful. Later, Colonel Anselmo Pineda and Ricardo de la Parra, commissioned by Rufino Cuervo, would be successful in celebrating an agreement on December 31, 1841 that reincorporated the isthmus of Panama into New Granada.

This would be the most successful of the attempts to separate Panama from Colombia and its different historical denominations during the 19th century.

Constitutional reform of 1843

During the presidency of General Pedro Alcántara Herrán, the power of the president was strengthened in order to maintain order throughout the national territory, which at that time was in civil war; An intense educational reform was carried out and authoritarianism and centralism were imposed throughout the national territory, which conservatism used to its advantage.

Between 1849 and 1853 the number of provinces increased from 22 to 36.

The separation of Panama in 1850

In 1850, General José Domingo Espinar and E. A. Teller, editor of the newspaper Panama Echo, carried out a revolution in the early morning of September 29, which ended with the second separation of Panama from the New Grenade. Obaldía, governor of the Isthmus, did not agree with this separation, since he saw the isthmus not yet prepared to assume control of its destiny, convincing him to desist and reintegrate the isthmus again.

Civil War of 1851

After the reforms initiated by President José Hilario López, which included the freedom of slaves (May 21, 1851), expulsion of the Jesuits, suppression of the death penalty and prison for debt, and the consecration of the freedom of the press and trial by jury, the Caucano landowners revolted against this because they considered them too liberal.

This is how on May 22 the rebels spoke out in the south of the country and Julio Arboleda tried to capture San Juan de Pasto, but was defeated; There were also uprisings in Sogamoso, Mariquita, Guatavita and El Guamo. To quell these uprisings, the Government then appointed General José María Obando as general in chief of the Southern Army and General Tomás Herrera, commander in Valle del Cauca, who gradually calmed down these armed confrontations. The war was ended at the end of the year, with the defeat of Mariano Ospina Rodríguez on August 30 and the capitulation of General Borrero on September 10.

Constitutional reform of 1853

The constitutional pendulum swung towards the liberal method. Among the new measures, federalism was initiated, slavery was eliminated, suffrage was extended to all men over 21 years of age, direct popular vote was imposed to elect congressmen, governors and magistrates, administrative freedom and freedom were established. religious, there was a separation between Church and State and the legal personality of the Catholic Church ended. Some of the advances were later reversed in the Colombian constitution of 1886.

In September 1853, elections were held to elect the attorney general and the Supreme Court of Justice; and on October 3, 1853, the governor of Bogotá was elected, counting the votes by parish district.

Civil War of 1854

After the presidential elections of 1853, in which the radical liberal candidate Tomás Herrera (supported by General José María Melo) was defeated by the moderate liberal candidate José María Obando, Melo did not accept his defeat and carried out a coup d'état on April 17, 1854 against President Obando. A military "constitutionalist" alliance of radicals and conservatives was immediately formed, who began the offensive against Melo: they fought in Pamplona, Bucaramanga, Vélez, Tunja, Tequendama and Cali, and They managed to surround the Melo army on the perimeter of the city of Bogotá. Melo organized his forces into the so-called "Regenerating Army", which numbered about 11,042 troops.

Melo remained in power for eight months, but finally the constitutionalist troops from the north and south of the country united, until they totaled 11,000 men, who surrounded the 7,000 melistas who defended Bogotá. On December 4 of the same 1854, The alliance entered Bogotá victorious, after defeating the Melista army and its allies, the moderate liberals and artisans. The latter presented tenacious resistance during the final assault on the capital, which is why the winning party banished hundreds of artisans to the Chagres River in Panama. The conflict cost about 4,000 lives.

End of the republic

During the years 1848 and 1849, the names of the traditional parties—Liberal and Conservative—were coined, their ideological differences took shape and the emphasis on personalisms was left behind.

Starting in 1849, during the government of General José Hilario López, the country underwent a strong political and economic transformation, since the colonial structure began to be replaced by that of capitalism.[citation required]

The ideological, political and military struggle throughout the country to define the destiny of the country radicalized sectors and regions. The environment was created for the emergence (1849) and the definitive configuration of the Colombian historical parties: the Liberal (Ezequiel Rojas) and the Conservative (Mariano Ospina Rodríguez and José Eusebio Caro).

The Republic of New Granada became the Grenadine Confederation when the Constitution of 1858 was approved, which began the federalist stage. In 1863 it adopted the name of the United States of Colombia.

Presidents

Fourteen were the presidents of the Republic of New Granada:

Territorial organization

In accordance with the Constitution, the territory of New Granada was divided into provinces. Each province was made up of one or more cantons, and each canton was divided into parish districts.

Likewise, the Republic included some national territories, mostly located in the peripheries of the country.

Geography

According to the Constitution, the limits of the territory of the Republic were the same as those that in 1810 divided the territory of the Viceroyalty of New Granada from that of the general captaincies of Venezuela and Guatemala, and from that of the Portuguese possessions of Brazil.; and those that, by the treaty approved by the Congress of New Granada on May 30, 1833, divide it from that of the Republic of Ecuador.

Economy

The economy of the Republic of New Granada was based on the commercialization of agricultural products, coming from different parts of the country, in addition to the opening of ports to foreign powers other than Spain, which caused unequal treatment.

Like the rest of Latin America, the economy of New Granada during the Colony focused on mining and agriculture. The control of the metropolis over all areas of production and tax collection led to the economy being not very dynamic. The Spanish had a monopoly on mining exploitation, serving the coffers of the peninsula, where most of the metals went. In turn, the Crown had a monopoly on the trade of manufactured products to the colonies. For its part, agricultural production was quite rudimentary and focused on satisfying internal needs.[citation needed]

Demography

According to the 1851 census, the total population of the country was 2,240,054 inhabitants, of which 1,086,705 were men and 1,153,349 women. Of all the provinces, the most inhabited were Bogotá, Tunja, Socorro and Tundama.

Culture

According to the Constitution, the Catholic religion was the only cult maintained by the Republic.

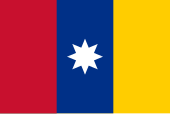

Symbols of the nation

When Gran Colombia fragmented, its successor countries continued to use the same emblems that this nation had provisionally, until their own insignia were decreed. In this way, from December 17, 1831 to May 9, 1834, New Granada, converted into a republic, used the same Gran-Colombian flag and coat of arms, only adding the motto "State of New Granada" to its border to differentiate it from the one used by its neighbors.

On May 9, 1834, Francisco de Paula Santander, as president of the Republic of New Granada, finally established the colors and their arrangement on the flag. Likewise, the decree defined the shape and basic elements of the coat of arms of the Republic, most of which have remained intact since then.

Contenido relacionado

114

77

Jackson Day