Renaissance philosophy

Renaissance philosophy, or Renaissance philosophy, is the philosophy that developed primarily between the 15th and 16th centuries, beginning in Italy and progressing to the rest of Europe.

In the Renaissance, philosophy was still a very broad field encompassing the studies now assigned to several different sciences, as well as theology. With that in mind, the three fields of philosophy that received the most attention and development were political philosophy, humanism, and natural philosophy.

In political philosophy, the rivalries between nation states, their internal crises, and the beginning of European colonization of the Americas renewed interest in problems about the nature and morality of political power, national unity, internal security, the power of the State and international justice. In this field, the works of Nicolás Machiavelli, Jean Bodin and Francisco de Vitoria stood out.

Humanism was a movement that emphasized the value and importance of human beings in the universe, in contrast to medieval philosophy, which always put God and Christianity at the center. This movement was, first of all, a moral and literary movement, led by figures such as Erasmus of Rotterdam, Saint Thomas More, Bartolomé de las Casas and Michel de Montaigne.

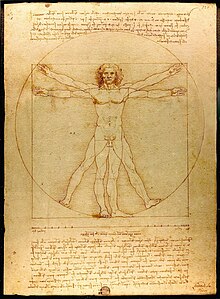

Renaissance philosophy of nature broke with the medieval conception of nature in terms of ends and divine ordering, and began to think in terms of forces, physical causes, and mechanisms. There was also a partial return to the authority of Plato over Aristotle, both in his moral philosophy, in his literary style and in the relevance given to mathematics for the study of nature. Nicolaus Copernicus, Giordano Bruno, Johannes Kepler, Leonardo da Vinci and Galileo Galilei were precursors and protagonists in this scientific revolution, and Francis Bacon provided a theoretical foundation to justify the empirical method that was to characterize the revolution. In medicine, on the other hand, Andreas Vesalius's work on human anatomy revitalized the discipline and provided more support for the empirical method.Renaissance philosophy of nature is perhaps best explained by two propositions written by Leonardo da Vinci in the notebooks of he:

- All our knowledge has its origins in our perceptions.

- There is no certainty that neither of the mathematical sciences nor any of the sciences derived from the mathematical sciences can be used.

Similarly, Galileo based his scientific method on experiments, but he also developed mathematical methods for application to problems in physics, an early example of mathematical physics. These two ways of conceiving human knowledge formed the background for the beginnings of empiricism and rationalism, respectively.

Other influential Renaissance philosophers included Pico della Mirandola, Nicolas of Cusa, Michel de Montaigne, Francisco Suárez, Erasmus of Rotterdam, Pietro Pomponazzi, Bernardino Telesio, Johannes Reuchlin, Tommaso Campanella, Gerolamo Cardano, and Luis Vives.

Renaissance Humanism

Renaissance humanism is an intellectual and philosophical European movement closely linked to the Renaissance whose origin is situated in Italy of the centuryXV (especially in Florence, Rome and Venice), with previous precursors, such as Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarca and Giovanni Boccaccio. Find the models of Classical Antiquity and retake the ancient Greek-Roman humanism. Maintains its hegemony in much of Europe until the end of the centuryXVI. From then on, it was transformed and diversified with the spiritual changes caused by social and ideological development: the principles advocated by the Protestant Reform (luteranism, Calvinism, Anglicanism) and the Catholic Counter-Reform; and later (up to the end of the century)XVIII) the Enlightenment and the French Revolution.

The movement, fundamentally ideological, also had a parallel printed aesthetic, e.g. in new forms of lyrics, such as the round, known as Humanistic letters, evolution of the tardogotic Fraktur lyrics developed in the environment of the Florentine humanists such as Poggio Bracciolini and the papal cipher shop, which came to replace by printing the medieval Gothic letter.

The expression humanitatis studia was opposed by Coluccio Salutati to theological and scholastic studies when he had to speak of the intellectual inclinations of his friend Francesco Petrarca; in this, human It meant what the Greek term philanthropy, love for our fellows, but indicating a fundamental axis opposed to the theocentrism of the clerical culture of the medioev that stood around man, anthropocentrism, as had occurred in the classical Greek-Latin culture. That's why the term was strictly linked to the litterae or study of classic letters. In the centuryXIX Germanic neologism was created Humanismus to designate a theory of education in 1808, a term that was later used, however, as opposed to scholastic (1841) to, finally, (1859) apply it to the period of the resurgence of classical studies by Georg Voigt, whose book on this period bore the subtitle of The First Century of Humanism, a work that was considered fundamental for a century on this subject.

Humanism advocated, in front of the ecclesiastical canon in prose, that imitated the late Latin of the Holy Fathers and used the simple vocabulary and syntax of the translated biblical texts, the studia humanitatis, a full formation of man in all aspects founded on the classical Greek-Latin sources, many of them then sought in the monastic libraries and then discovered in the monasteries of the entire European continent. In a few cases these texts were translated thanks to the work, among others, of Averroes and the tireless search for manuscripts by scholarly humanist monks in the monasteries of all Europe. The work was thus intended to access a purest, brighter and genuine Latin, and the rediscovery of the Greek thanks to the forced exile to Europe of the Byzantine sages by falling Constantinople and the Eastern Empire in power of the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The second and local task was to search for material remains of Classical Antiquity in the second third of the centuryXV, in places with rich deposits, and study them with the rudiments of the methodology of Archaeology, to know better the sculpture and architecture. In consequence, humanism must restore all the disciplines that would help to a better knowledge and understanding of these authors of Classical Antiquity, to which it was considered a model of knowledge more pure than the weakened in the Middle Ages, to recreate the schools of Greek philosophical thought and imitate the style and language of the classic writers, and therefore humanely developed Golden Legend. This type of training is still considered humanist today.

To do this, the humanists imitated the Greek style and thought in two different ways: the call imitatio ciceroniana, or imitation of a single author as a model of all classical culture, Cicero, driven by the Italian humanists, and imitatio eclectica, or imitation of the best of each Greek-Latin author, advocated by some humanists led by Erasmus of Rotterdam.

- The emigration of Byzantine sages: because the Byzantine Empire was being besieged by the Turks, many of them sought refuge in Western Europe, especially in Italy, carrying with them Greek texts, promoting the diffusion of Greek culture, values and language. For example, Manuel Crisoloras, Greek scholar of Constantinople, who taught Greek in Florence from 1396 to 1400 and wrote for the use of his disciples the work Greek Language Issuesbased on the Grammar of Dionisio Tracio; his disciple Leonardo Bruni (1370-1444) was the first to make Greek translations into Latin on a large scale, as well as Ambrosio Traversario, who also recommended Cosme de Médici to acquire two hundred Greek codices of Byzantium or Francesco Filelfo, which took the same many others.

- The invention of the printing press: this invention of Gutenberg allowed the breaking up of the cost and dissemination of books, ensuring the mass diffusion of humanistic ideas and the emergence of the critical sense against the dixit magister or argument of medieval authority.

- The arrival at the solio pontificio of Tomas Parentucelli, (Papa Nicolás V) and Eneas Silvio Piccolomini, (Pius II) makes Rome one of the great centers of Humanism.

- The action of the patrons: the patrons were people who, with their political protection, with their appreciation for the ancient knowledge, with their eager collectors or with the economic remuneration of the humanists to establish or cost their works in the printing press, facilitated the development of Humanism. These people gathered together classic works and called scholars who knew Greek and Roman literature; if that were not enough, they welcomed them in their palaces. Among the most outstanding patrons stand out: the family of the Médici of Florence Lorenzo de Médicis, called the Magnificent and his brother Juliano de Médicis, the Roman pontiffs Julio II and Leon X, Cristina of Sweden.

- The creation of universities, schools and academies: universities (such as Alcala de Henares, Lovaina, etc.) and schools of the centuryXV They contributed largely to the expansion of Humanism throughout Europe.

Continuities

The structure, sources, method, and themes of philosophy in the Renaissance had much in common with that of earlier centuries.

Structure of philosophy

Especially after the recovery of a large part of Aristotelian writings in the XII and XIII, it became clear that, in addition to Aristotle's writings on logic, which were already known, there were numerous others that had to do roughly with logic. natural philosophy, moral philosophy and metaphysics. These areas provided the structure for the philosophy curriculum of emerging universities. In general, the more "scientific" of philosophy were the most theoretical and, therefore, most applicable. Also during the Renaissance, many thinkers considered that these were the main philosophical areas, and that logic provided a training of the mind to deal with the other three.

Sources of Philosophy

A similar continuity can be seen in the case of fonts. Although Aristotle was never an unquestioned authority (he was more often than not a springboard for discussion, and his opinions were often discussed alongside those of others, or the teaching of Holy Scripture), medieval physics lessons consisted of reading Aristotle's Physics, moral philosophy lessons consisted of examining his Nicomachean Ethics (and often his Politics), and metaphysics was approached through his Metaphysics. The assumption that Aristotle's works were central to the understanding of philosophy did not wane during the Renaissance, which saw a flourishing of new translations, commentaries, and other interpretations of his works, both in Latin and in the vernacular. Reform, Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics remained the main authority for the discipline of ethics in Protestant universities until the end of the century XVII, with more than fifty Protestant commentaries published on the Nicomachean Ethics before 1682.

Method of philosophy

Regarding the method, philosophy was considered during the Late Middle Ages as a subject that required solid research by people trained in the technical vocabulary of the subject. Philosophical texts and problems were usually addressed through university lectures and 'questions'. The latter, somewhat similar to modern debates, examined the pros and cons of certain philosophical positions or interpretations. They were one of the cornerstones of the 'scholastic method', they made students posing or answering questions quick in their work, and they required a deep familiarity with the entire known philosophical tradition, which is often invoked in support or against specific arguments. This style of philosophy continued to have a large following into the Renaissance. The Disputations of Pico della Mirandola, for example, depended directly on this tradition, which was by no means limited to university classrooms.

Philosophy Topics

Given the remarkable breadth of Aristotelian philosophy, in medieval and Renaissance philosophy it was possible to discuss all sorts of issues. Aristotle had dealt directly with problems such as the trajectory of missiles, the habits of animals, how knowledge is acquired, the freedom of the will, how virtue is related to happiness, the relationship of the lunar and sublunary worlds. He had indirectly stimulated the debate on two points that especially concerned Christians: the immortality of the soul and the eternity of the world. All of them continued to be of considerable interest to Renaissance thinkers, but we will see that in some cases the solutions offered were significantly different due to changes in the cultural and religious landscape.

Discontinuities

Having established that many aspects of philosophy held in common during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, it will be useful now to discuss in which areas changes occurred. The same scheme as above will be used to show that surprising differences can also be found within continuity trends.

Sources of Philosophy

Therefore, it is useful to reconsider what was mentioned above about philosophical sources. In the Renaissance there was a significant expansion of sources. Plato, known directly through only two and a half dialogues in the Middle Ages, became known through numerous Latin translations in 18th century Italy XV, culminating in the enormously influential translation of his complete works by Marsilio Ficino in Florence in 1484. Petrarch could not read Plato directly, but he greatly admired him. Petrarch was also a great admirer of Roman poets such as Virgil and Horace and of Cicero for writing Latin prose. Not all Renaissance humanists followed his example in everything, but Petrarch contributed to expanding the "canon"; of his time (pagan poetry had previously been considered frivolous and dangerous), something that also happened in philosophy. In the 16th century, anyone considered "au fait" he read both Plato and Aristotle, trying where possible (and not always very successfully) to reconcile the two with each other and with Christianity. This is probably the main reason why Donato Acciaiuoli's commentary on Aristotle's Ethics (first published 1478) was (first published 1478) so successful: he beautifully blended the three traditions.

Other movements in ancient philosophy also re-entered the mainstream. While this was not the case for Epicureanism, which was largely caricatured and regarded with suspicion, Pyrrhonism and Academic Skepticism made a comeback thanks to philosophers such as Michel de Montaigne, and Neostoicism became a popular movement due to the writings of Justus Lipsius. In all these cases it is impossible to separate the pagan philosophical doctrines from the Christian filter through which they were approached and legitimized.

Structure of philosophy

Although in general the Aristotelian structure of the branches of philosophy was maintained, interesting developments and tensions took place within them. In moral philosophy, for example, a position consistently held by Thomas Aquinas and his many followers was that its three subfields (ethics, economics, politics) were related to progressively larger spheres (the individual, the family, and the community).). Politics, thought Tomás, is more important than ethics because it considers the good of the greatest number. This position came under increasing stress in the Renaissance, as various thinkers claimed that Aquinas's classifications were inaccurate and that ethics was the most important part of morality.

Other important figures, such as Francesco Petrarca (Petrarca) (1304-1374), questioned the entire assumption that the theoretical aspects of philosophy were most important. He insisted, for example, on the value of the practical aspects of ethics. Petrarch's position, expressed as bluntly as it is amusing in his invective On his own ignorance and that of many others (De sui ipsius ac multorum ignorantia) is also important for another reason: it represents the conviction that philosophy should be guided by rhetoric, that the purpose of philosophy is not, therefore, to reveal the truth, but to encourage people to pursue the good. This perspective, so typical of Italian humanism, could easily lead to reducing all philosophy to ethics, in a move reminiscent of Plato's Socrates and Cicero.

Method of philosophy

If, as already stated, scholasticism continued to flourish, Italian humanists (ie, lovers and practitioners of the humanities) challenged its supremacy. As we have seen, they believed that philosophy could be brought under the wing of rhetoric. They also thought that the academic discourse of their time should return to the elegance and precision of its classical models. For this reason, they tried to dress philosophy in more attractive clothing than that of their predecessors, whose translations and commentaries were made in technical Latin and sometimes limited themselves to transliterating Greek. In 1416-1417, Leonardo Bruni, the preeminent humanist of his time and chancellor of Florence, retranslated Aristotle's Ethics into a more fluent, idiomatic, and classical Latin. He hoped to communicate the elegance of Aristotle's Greek and, at the same time, make the text more accessible to those without a philosophical background. Others, such as Nicolò Tignosi in Florence around 1460, and the Frenchman Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples in Paris in the 1490s, tried to please the humanists, either by including attractive historical examples or quotations from poetry in their commentaries on Aristotle, either avoiding the standard scholastic format of questions, or both.

The driving conviction was that philosophy needed to be freed from its technical jargon so that more people could read it. At the same time, all kinds of summaries, paraphrases and dialogues dealing with philosophical topics were prepared, in order to give their themes a greater diffusion. Humanists also encouraged the study of Aristotle and other ancient writers in the original. Desiderius Erasmus, the great Dutch humanist, went so far as to prepare a Greek edition of Aristotle, and over time those who taught philosophy in universities had to at least pretend to know Greek. However, the humanists were not big fans of the vernacular. There are only a handful of examples of dialogues or translations of Aristotle's works into Italian during the 15th century. However, once it was determined that Italian was a language with literary merit and that it could carry the weight of philosophical discussion, numerous efforts began to appear in this direction, especially from the 1540s. Alessandro Piccolomini had a program to translate or paraphrase the entire Aristotelian corpus into the vernacular.

Other important figures included Benedetto Varchi, Bernardo Segni and Giambattista Gelli, all of whom were active in Florence. Efforts were also launched to present Plato's doctrines in the vernacular. This rise of vernacular philosophy, which predates the Cartesian approach well, is a new field of inquiry whose contours are only beginning to become clear.

Philosophy Topics

It is very difficult to generalize about the ways in which discussions of philosophical issues changed in the Renaissance, mainly because doing so requires a detailed map of the period, something we do not yet have. We know that the debates on the freedom of the will continued to be heated (for example, in the famous exchanges between Erasmus and Martin Luther), that Spanish thinkers were increasingly obsessed with the notion of nobility, that dueling was a practice that generated great literature in the 16th century (were they allowed or not?).

Previous stories perhaps paid undue attention to Pietro Pomponazzi's statements about the immortality of the soul as a question that could not be resolved philosophically in a manner consistent with Christianity, or to the Prayer on the Dignity of Man of Pico della Mirandola, as if they were signs of the growing secularism or even atheism of the time. In fact, the most successful compendium of natural philosophy of the time (Compendium philosophiae naturalis, first published in 1530) was written by Frans Titelmans, a Franciscan friar from the Netherlands whose work has a strong religious flavor. It should not be forgotten that most philosophers of the time were at least nominal, if not devout, Christians than the century. XVI witnessed both the Protestant and Catholic reforms, and that Renaissance philosophy culminated in the period of the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). In other words, religion was enormously important in the period, and one can hardly study philosophy without remembering it.

[File:Marsilio Ficino - Angel Appearing to Zacharias (detail).jpg|thumb|left|upright|Marsilio Ficino, detail of Angel Appearing to Zacharias by Domenico Ghirlandaio, ca. 1490]] This is the case, among others, of the philosophy of Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499), who reinterpreted Plato in the light of his first Greek commentators and also of Christianity. Ficino hoped that a purified philosophy would bring about a religious renewal in his society and, therefore, he transformed the unpleasant aspects of Platonic philosophy (for example, the homosexual love exalted in the Symposium) into spiritual love (that is, Platonic love), something that Pietro Bembo and Baldassare Castiglione later transformed at the beginning of the XVI century as something also applicable to relationships between men and women. Ficino and his followers were also interested in 'occult knowledge', mainly because of their belief that all ancient knowledge was interconnected (Moses, for example, had received his knowledge from the Greeks, who in turn they had received from others, all according to God's plan and therefore mutually consistent; Hermeticism is relevant in this case). Although Ficino's interest in and practice of astrology was not uncommon in his time, it need not necessarily be associated with philosophy, as the two were often considered quite separate and often contradictory to each other.

In conclusion, like any other moment in the history of thought, the philosophy of the Renaissance cannot be considered to have contributed something totally new or to have continued repeating the conclusions of its predecessors for centuries. Historians call this period the "Renaissance" to indicate the renaissance that took place in ancient (particularly classical) perspectives, sources, and attitudes toward literature and the arts. At the same time, we realize that any reappropriation is limited and even guided by contemporary preoccupations and prejudices. It was no different in the period considered here: the old mingled with the new and changed it, but although it cannot be said that there is a new revolutionary starting point in philosophy, in many ways the synthesis of Christianity, Aristotelianism and the Platonism offered by Thomas Aquinas was torn apart to make way for a new one, based on more complete and varied sources, often on the original, and certainly in tune with the new social and religious realities and with a much broader audience.