Renaissance

Renaissance is the name given in the XIX century to a broad cultural movement that produced in Western Europe during the 15th and XVI. It was a period of transition between the Middle Ages and the beginnings of the Modern Age. Its main exponents are in the field of arts, although there was also a renewal in the sciences, both natural and human. The city of Florence, in Italy, was the birthplace and development of this movement, which later spread throughout Europe.

The Renaissance was the result of the dissemination of the ideas of humanism, which determined a new conception of man and the world. The term "Renaissance" was used to claim certain elements of classical Greek and Roman culture, and was originally applied as a return to the values of Greco-Roman culture and the free contemplation of nature after centuries of predominance of a more rigid type of mentality. and dogmatic established in medieval Europe. In this new stage, a new way of seeing the world and the human being was proposed, with new approaches in the fields of arts, politics, philosophy and science, replacing medieval theocentrism with anthropocentrism.

Historian and artist Giorgio Vasari was the first to use the word "Renaissance" ( rinascita ) to describe the break with the medieval artistic tradition, which he described as a style of barbarians , which would later be called Gothic. Vasari believed that the arts had fallen into decline with the collapse of the Roman Empire and had only been rescued by the artists of Tuscany from the 13th century. .

The current concept of Renaissance (from French Renaissance) was formulated in the mid-XIX century by the French historian Jules Michelet, in his work Renaissance et Réforme, published in 1855. For the first time, Michelet used the term in the sense of a historical period, spanning from the discovery of America to Galileo, and considered it more important for its scientific developments than for art or culture. Michelet, who was a French nationalist and republican, attributed to the Renaissance democratic values opposed to those of the preceding Middle Ages and a French role.

The other historian who had great influence in shaping the concept of the Renaissance was the Swiss Jacob Burckhardt, who defined it as the period between Giotto and Michelangelo, that is, the XIV mid-xvi. Buckhardt highlighted the emergence of the modern individualistic spirit from the Renaissance, which the Middle Ages would have inhibited.

From the perspective of the general artistic evolution of Europe, the Renaissance meant a «break» with the stylistic unity that until then had been «supranational». The Renaissance was not a unitary phenomenon from the chronological and geographical points of view: its scope was limited to European culture and the newly discovered American territories, to which the Renaissance novelties arrived late. Its development coincided with the beginning of the Modern Age, marked by the consolidation of the European states, the transoceanic voyages that brought Europe and America into contact, the decomposition of feudalism, the rise of the bourgeoisie and the affirmation of capitalism. However, many of these phenomena exceed the scope of the Renaissance due to their magnitude and greater extension in time.

General aspects

Historical context

The Renaissance marks the beginning of the Modern Age, a historical period that is usually established between the discovery of America in 1492 and the French Revolution in 1789, which, in the artistic field, encompasses styles such as the Renaissance and Mannerism (15th and 16th centuries), the Baroque, the Rococo and Neoclassicism (17th and 18th centuries). Other historians place the start date in 1453, the fall of Constantinople, or they highlight a transcendental event such as the invention of the printing press (around 1440 approximately, by the hand of Johannes Gutenberg).

The historical background of the Renaissance can be situated in the decadence of the medieval world that occurred throughout the XV century due to various factors, such as the decline of the Holy Roman Empire, the weakening of the Catholic Church due to schisms and heretical movements —which would give rise to the Protestant Reformation—, the deep economic crisis derived from the stagnation of the feudal system and the decline of the arts and sciences, weighed down by a scholastic theology mired in skepticism.

Faced with this decline, the main European academic centers sought to regenerate themselves by returning to the values of classical Greco-Roman culture. At the same time, a new society began to take shape, based on the rise of the new centralized states, with powerful armies and bureaucratized administrations —beginning of the monarchical authoritarianism advocated by Machiavelli—, as well as on demographic growth and an economy centered on a new class. emerging social class, the bourgeoisie, which laid the foundations of capitalism and a mercantile and pre-industrial economy; all this helped by the technical and scientific progress experienced during this period, based on the printing press and the consequent speed of diffusion of novelties. Thus arose a more anthropocentric vision of the world, detached from religion and medieval theocentrism, in which man and scientific advances will mean the new way of assessing the world: humanism, a term initially applied to specialists in Greco-Roman disciplines (law, rhetoric, theology and art), which would be extended to philosophers, artists, scientists and any scholar of the various branches of knowledge that then began to coalesce into a concept of general culture.

In Italy, the epicenter of Renaissance culture, the division of the territory into city-states with different political regimes —republics like Florence or Venice, monarchical states like Milan and Naples or papal rule in Rome— led to the rise of a economic elite who sponsored culture and art as propaganda instruments of the state, each rivaling the others in magnificence and splendor. Education became more accessible, ceasing to be limited to the clergy, and intellectual debate was favored, with the founding of universities and the sponsorship of literature.

For its part, the 16th century was marked by the great geographical discoveries that began with the arrival of Columbus in America in 1492, such as the establishment of the Cape route by Vasco da Gama in 1498, Magellan's circumnavigation of the world between 1519 and 1521, the landing of Cortés in Mexico in 1519, and the conquest of Peru by Pizarro (1530-1533); as well as the breakdown of Christian unity caused by the Protestant Reformation of Martin Luther (1520), the development of science and technology (Nova Scientia de Tartaglia, 1538; De revolutionibus by Copernicus, 1543; Anatomy by Vesalius, 1543) and the expansion of humanism (Erasmus of Rotterdam, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Ludovico Ariosto, Tomás Moro, Juan Luis Vives, François Rabelais).

Definition

The term «Renaissance» comes from the Italian Rinascita and was coined by the artist and historian Giorgio Vasari in his Lives (1550/1568), alluding to the rebirth of classical culture after medieval obscurantism. As such, it is a social, political and cultural phenomenon that spanned the entire European continent during the 15th and xvi. In modern historiography, the first definition of the Renaissance comes from the French historian Jules Michelet (La Renaissance, 1855), while the current view of the world Renaissance culture was forged by Jacob Burckhardt in his essay The Culture of the Renaissance in Italy (1860).

Although the beginning of the Renaissance is usually placed in the XV century, many historians take it back to the XIV or even at xiii, to the work of some artists considered precursors, such as Cimabue and Giotto in painting or Nicola Pisano in sculpture. These laid the foundations for the first fully Renaissance artists in Florence in the first quarter of the XV century, such as the painter Masaccio, the sculptor Donatello or architect Brunelleschi, all of them interested in naturalism, harmony and mathematical proportions.

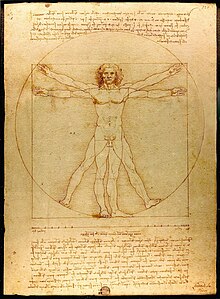

In this cultural climate of renewal, based on models from classical antiquity, a movement arose at the beginning of the XV century. of great vitality in Italy, which would immediately spread to other European countries. The artist became aware of an individual with intrinsic values, he felt attracted to culture and knowledge in general, and began to study the models of antiquity, at the same time that he studied disciplines such as anatomy and investigated new techniques, such as chiaroscuro and perspective, greatly developing the ways of representing the natural world with fidelity. The paradigm of this new attitude is Leonardo da Vinci, who was interested in multiple branches of knowledge, but in the same way Michelangelo Buonarroti, Rafael Sanzio, Sandro Botticelli and Bramante were artists moved by the image of antiquity and concerned with developing new techniques. sculptural, pictorial and architectural, as well as music, poetry and the new humanistic sensibility.

There is no doubt that the Renaissance evolved to a large extent from medieval art, a part of which had not stopped valuing and imitating classical art; but the Renaissance artist imperiously sought to distance himself from the later stage, which they despised for its subservience to religious values and for its anti-naturalist style, stemming not from a lack of technical ability to imitate nature, but from a desire to avoid it. to emphasize other more subjective values, linked to spirituality. However, the Renaissance artist himself did not value this fact and felt different, "reborn"; thus, Lorenzo Valla came to affirm that he did not know why the arts «had declined to such an extent, and almost died; nor why they had resurfaced at that time; appearing and succeeding so many good artists and writers".

A good part of the emergence of this new scale of values, in which artists and writers will be exalted above characters of noble birth, comes from the system of republican-type Italian city-states, thus far removed from the authoritarian ways of the aristocracy and the clergy, with societies in which their own merit was valued more than that coming from birth in a certain lineage. In this new society, civic virtue is valued more than chivalrous or contemplative, personal talent —whether in business, science or art— than rancid ancestry.

It should be noted that a factor that greatly contributed to the success of the new artistic theories was patronage, both from cities and entities of various kinds and from characters from both the aristocracy and the clergy as well as the new emerging bourgeoisie. For these characters, the patronage of culture was a sign of power and social status, which gave those who exercised it prestige and ostentation in front of their peers. Some of the most distinguished patrons were: the Florentine Lorenzo de' Medici, nicknamed "the Magnificent"; Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino; Ludovico Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua; Alfonso the Magnanimous, King of Naples; Francesco and Ludovico Sforza, Dukes of Milan; in addition to the popes and cardinals of the Church.

The Renaissance artist is heir to the precepts of classical culture, but reinterprets them through humanism, reaffirming the intrinsic values of the perceptible world and of the human being as part of that sensitive reality. Although he does not renounce religion and the values of the Christian reality, he gives preponderance to this new humanistic vision over religious transcendence. Thus, the static vision of the universe prevailing during the Middle Ages is succeeded by a dynamic vision that is based on experimentation and the revalidation of the scientific method as a source of knowledge. On the other hand, the new supreme values of the artist will be beauty and harmony, detached from religion and supported by the study of nature, which through measure and proportion give the artist new tools to carry out his works.

While the Quattrocento or First Italian Renaissance arose in Florence —so called because it developed during the 1400s (XV)—, originated by the search for classical beauty canons and the scientific bases of art, a similar and contemporary phenomenon took place in Flanders —especially in painting—, based mainly on the observation of the nature. This First Renaissance was widely distributed in Eastern Europe: the Moscow Kremlin fortress, for example, was the work of Italian artists.

The second phase of the Renaissance, or Cinquecento (XVI century), was marked by the artistic hegemony of Rome, whose popes (Julius II, Leo X, Clement VII and Paul III, some of them belonging to the Florentine Medici family) fervently supported the development of the arts, as well as the investigation of classical antiquity. However, with the wars in Italy (sack of Rome in 1527), many of these artists emigrated and spread Renaissance theories throughout Europe.

Thus, throughout the 16th century the Italian Renaissance spread throughout Europe, from Portugal to Scandinavia, and from France to Russia. Many artists traveled in search of training or patronage, and the great European courts —such as Fontainebleau, Madrid, Prague or Dresden— were filled with artists of multiple nationalities. Italian artists were especially valued, but many foreigners who went to train in Italy thus acquired a new reputation. A contributing factor in the diffusion of the new art was engraving, the mass production of which allowed artists' works to spread throughout the continent. The art market also increased considerably, and the work of dealers was essential to connect artists and buyers; one of the largest art market centers of the time was Antwerp. Collecting also grew, and the so-called "art chambers" (Kunstkammern) appeared, generally belonging to characters from the aristocracy and the wealthy. royalty, rooms where objects of art of all kinds, books and objects of all kinds, and even minerals or natural samples of flora and fauna were exhibited; one of the most famous was that of Rudolf II in Prague.

- Features

In a generic way, the characteristics of the Renaissance can be established in:

- The "return to antiquity": both the old architectural forms and the classic order and the use of old formal and plastic motifs resurfaced. Also, classical mythology and history, as well as the adoption of ancient symbolic elements, were taken as thematic motifs. To this end, the aim was not to make a servile copy, but to penetrate and learn about the laws that support classical art. Much of this revaluation of classical art came by archaeological finds of pieces such as coins, chamberlains or Roman sculptures, as well as the recovery of classic treaties such as those of Vitruvio, essential in the renewal of architecture.

- A new “relation with nature” emerged, which was linked to an ideal and realistic conception of science. Mathematics will become the main aid of an art that cares incessantly to rationally base its ideal of beauty. The aspiration to access the truth of nature, as in ancient times, is not directed towards the knowledge of casual phenomena, but towards the penetration of the idea.

- The Renaissance makes the “man” measure of all things. The artist has a scientific formation, which makes him free from the most characteristic group and mechanistic attitudes of the malevo and rise in the social scale. This presupposes to give the artist a new consideration, that of "creator". The human figure is the new center of interest of the artist, who carefully studies the anatomy to make a reliable representation, while he values aspects such as movement and expression.

- The "mecenazgo": the high classes were constantly sponsoring and commissioning works, since art was seen as an instrument of prestige and refinement, which led to a moment of great brilliance in all artistic disciplines. The main centers of patronage were the Florence of the Medicis in the Quattrocento and papal Rome in the Cinquecentparticularly July II and Leo X. In other cities, other large families encouraged the patronage: the East in Ferrara, the Gonzaga in Mantua, the Sforza in Milan, the Colonna in Naples, etc.

Aesthetics

Renaissance culture marked a return to rationalism, the study of nature, empirical research, with special influence from classical Greco-Roman philosophy. The Renaissance aesthetic was based on both classical antiquity and medieval aesthetics, so it was sometimes somewhat contradictory: beauty oscillated between a realistic conception of imitation of nature and an ideal vision of supernatural perfection, the visible world being the ultimate. way to ascend to a supersensible dimension.

One of the first Renaissance art theorists was Cennino Cennini: in his work Il libro dell'arte (1400) he laid the foundations for the artistic conception of the Renaissance, defending art as a creative intellectual activity, and not as simple manual work. For Cennini, the best method for the artist is to portray nature (ritrarre de natura), defending the freedom of the artist, who must work "as he pleases, according to his will" (come gli piace, secondo sua volontà). He also introduced the concept of "design" ( disegno ), the creative impulse of the artist, who forges a mental idea of his work before making it materially, a concept of vital importance for art ever since. modern.

In this context several other treatises on art arose, such as those by Leon Battista Alberti (De Pictura, 1436-1439; De re aedificatoria, 1450; and De Statua, 1460), or The Commentaries (1447) by Lorenzo Ghiberti. Alberti received the Aristotelian influence, claiming to provide a scientific basis to art. He also spoke of decorum, the artist's treatment of adapting artistic objects and subjects to a measured, perfectionist sense. It was Alberti who grouped architecture, sculpture and painting into the group of arts liberal, since until then they were considered as crafts; with this, he raised the artist to the category of intellectual creator.Ghiberti was the first to periodify the history of art, distinguishing classical antiquity, medieval period and what he called "rebirth of the arts" (Renaissance).

The Renaissance placed special emphasis on imitating nature, which it achieved through perspective or studies of proportions, such as those carried out by Luca Pacioli on the golden section: in De Divina Proportione (1509) spoke of the golden number —represented by the Greek letter φ (fi)—, which has various properties such as ratio or proportion, which are found both in some geometric figures and in nature, in elements such as shells, ribs of the leaves of some trees, the thickness of the branches, etc. Likewise, he attributed a special aesthetic character to the objects that follow the golden ratio, as well as granted them a mystical importance.

On the other hand, Giorgio Vasari, in Life of the Most Excellent Italian Architects, Painters and Sculptors from Cimabue to Our Times (1542–1550), was one of the predecessors of art historiography, by chronicling the major artists of his time, placing special emphasis on the progression and development of the art.

Art

Stages

Different historical stages mark the development of the Renaissance: the first has as its chronological space the entire XV century: it is the so-called Quattrocento, and includes the First Renaissance —also called “Early Renaissance” or “Low Renaissance”—, which takes place in Italy; the second arises in the XVI century and is called Cinquecento: its artistic domain refers to classicism or High Renaissance -also called "Full Renaissance"-, which focuses on the first quarter of the century. At this stage the great figures of the Renaissance in the arts emerge: Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael. It is the apogee of Renaissance art. Around 1520-1530, this period led to an anti-classical reaction that formed Mannerism, which lasted until the end of the XVI century. While the Renaissance was developing in Italy, in the rest of Europe Gothic art was maintained in its late forms, a situation that was to be maintained, except for specific cases, until the beginning of the century XVI.

In Italy, the confrontation and coexistence with Greco-Roman antiquity, considered a national legacy, provided a broad base for a homogeneous and generally valid stylistic evolution. Therefore, its emergence was possible there and preceded all other nations. Outside of Italy, the development of the Renaissance would constantly depend on the impulses set by Italy: artists imported from Italy or trained there would play the role of true transmitters. Monarchs such as Francisco I in France or Carlos I and Felipe II in Spain imposed the new style on the constructions they sponsored, influencing prevailing artistic tastes and turning the Renaissance into a "fashion".

Italy

Architecture

Renaissance architecture had a markedly profane character compared to earlier times. It arose in a city where Gothic architecture had barely penetrated, Florence. Despite this, many of the most outstanding works were religious buildings.

With the new taste, they sought to order and renovate the old medieval towns and even new cities were planned. The search for the "ideal city", as opposed to the chaotic and disorderly model of the Middle Ages, would be a constant concern of artists and patrons. Thus, Pope Pius II rearranged his hometown, Pienza, turning it into a true showcase of the new Renaissance urbanism. In itself, the cities would become the ideal setting for artistic renewal, opposing the medieval concept in which the rural had a preferential role thanks to monasticism.

When taking elements from classical architecture, Renaissance architects did so selectively, for example, instead of using the classical Doric column, the Tuscan order was preferred. Likewise, new forms were created, such as the balustrade column, new orders of capitals or decorations that, although inspired by antiquity, had to be adapted to the religious use of the churches. Thus, the classical putti that accompanied Venus in Greek or Roman representations become putti (putti).

Architects use the modular proportions and overlapping orders that appeared in Roman buildings; domes were widely used as a monumental element in churches and public buildings. From this moment on, the architect abandons the guild and anonymous character that he had during the Middle Ages and becomes an intellectual, a researcher. Many of them wrote treatises and speculative works of great importance, as in the case of Leon Battista Alberti or Sebastiano Serlio.

The most characteristic construction elements of the Renaissance style were:

- Structures: half-point arch, columns, semi-spherical dome, barrel vault and flat cover with stalls. All of them had been used in antiquity, especially for Roman art, and are now recovered, modifying them. It gradually decays the traditional method of construction of the Gothic, and largely abandons the vaults of crossing, the pointed arch, the staggered ships and, above all, the impression of colossalism and multiplicity of the medieval buildings. They would now dominate values such as symmetry, structural clarity, simplicity and, above all, adaptation of space to man's measure.

- Decorative: pilasters, frontons, porticos, heraldic motifs, pads, volutes, grutescos, garlands, motifs candelieri (candelabras or pebeteros) and Tondos or medallions. Some of these had already been used in Gothic, others are original creations and most were inspired by Roman and Greek models. As for decoration, the Renaissance preconditioned the dispossession, austerity, order. Only at the end of the centuryXVI This tendency would break in favor of fantasy and decorative wealth with mannerism.

By stages, two major moments can be distinguished:

- The Quattrocento had its nerve center in Florence and Tuscany. The simplicity and structural and decorative clarity was the fundamental feature of the architecture of this moment. The classic models are subjected to a process of stylization and adapt to the Christian temple. It was frequent to use classic orders, with columns and pilasters, capitals (preferably the corinthium, although replacing the caulicules with fantastic figures or animals), smooth fuses and almost omnipresence of the midpoint arch. The barrel and edge vault is also used, and wooden roofs with stalls. What fundamentally distinguishes the architecture of the Quattrocento of the High Renaissance is the small decoration (Fuckti, garlands of flowers or fruits, grutescos, etc.), the domes with nerves, with certain Gothic remains (Catedral of Florence, Filippo Brunelleschi) and the symmetrical facades of superimposed floors (Palacio Medici−Riccardi, Michelozzo) or with almohadillados chairs (Palacio Rucellai, Bernardo project). In general, the four-center architecture gives the impression of order, simplicity, lightness and symmetry, predominating in the interior of the buildings the luminosity and nakedness. The most outstanding architects of this period were Brunelleschi (Basilica de San Lorenzo, 1420; Basilica of the Holy Spirit, 1436) and Leon Battista Alberti (San Andrés de Mantua, 1460); and the main work was the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence and its famous dome, work of Brunelleschi. From the rest of Italy stand out: the Cartuja de Pavía, by Giovanni Antonio Amadeo (1475); the church of Saint Zechariah of Venice, by Mario Codussi (1470); and the Castel Nuovo of Naples, by Francesco Laurana (1453).

- The Cinquecent had as the centre of Rome: in 1506 Donato Bramante finished his famous project for the Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican, which would be the building that would mark the pattern in the rest of the centuryXVI. At this stage, buildings tend more to monumentality and grandeur. Michelangelo introduced the “major order” in his project for the Vatican basilica, which broke with the concept of “architecture made to man’s measure”. The palaces were adorned with elaborate bas-reliefs (Place Grimani of Venice, 1549, work by Michele Sanmicheli) or exemplary sculptures (Biblioteca de San Marcos, 1537–1550, Venice, work by Jacopo Sansovino). This would predominate the idea of wealth, monumentality and luxury in the buildings. As the century progresses, mannerism was introduced into the architecture, with increasingly sumptuous buildings, rebused decorations and elements that seek to capture the attention of the spectator for its originality or extravagance (Palacio del Té, in Mantua, by Giulio Romano). We can distinguish, in this way, as in the other artistic disciplines, two periods: the "classicism" of the beginning of the century, with authors such as Bramante, Miguel Angel, Antonio da Sangallo el Viejo, or Jacopo Sansovino; and the "manierismo", which takes place from 1530, being its main authors Andrea Palladio, Giorgio Vasari, Giulio Romano, Jacoponzono Vigno. It should be pointed out that the rupture of mannerism was not radical since already in the work of Michelangelo there are elements that prelude it.

Painting

In painting, the novelties of the Renaissance were introduced gradually but irreversibly from the 15th century. An antecedent of these was Giotto, a painter still within the orbit of the Gothic, but who developed in his paintings concepts such as three-dimensional volume, perspective and naturalism, which distanced his work from the rigid modes of the Byzantine and Gothic tradition and preluded the Renaissance. pictorial.

In the Quattrocento (XV century) all these novelties were collected and adapted to the new humanist and bourgeois mentality that spread through the Italian city-states. The painters, most of them still dealing with religious themes, also introduced mythology, allegory and portraiture into their works, which would develop enormously from now on. A constant search for the painters of this period would be perspective, the object of study and reflection for many artists: they tried to reach the illusion of three-dimensional space in a scientific and regulated way. Fourth century painting is a time of experimentation; the paintings slowly and progressively abandon gothic rigidity and come closer and closer to reality. Nature appears portrayed in the backgrounds of the compositions, and nudes are introduced into the figures.

The most outstanding painters of this period were: in Florence, Fra Angelico, Masaccio, Benozzo Gozzoli, Piero della Francesca, Filippo Lippi and Paolo Uccello; in Umbria, Perugino; in Padua, Andrea Mantegna; and, in Venice, Giovanni Bellini. Above all of them stands out Sandro Botticelli, author of allegories, delicate madonnas and mythological subjects. His sweet style, very attentive to feminine beauty and sensibility, and predominantly drawing, characterizes the Florentine school of painting and this entire period. Other authors of the Italian Quattrocento are Andrea del Castagno, Antonio Pollaiuolo, Pinturicchio, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Cima da Conegliano, Luca Signorelli, Cosimo Tura, Vincenzo Foppa, Alessio Baldovinetti, Vittore Carpaccio and, in the south of the peninsula, Antonello da Messina.

The Cinquecento (XVI century) was the culminating stage of Renaissance painting, and for this reason is sometimes called « classicism". The painters assimilate the novelties and experimentation of the fourteenth century and take them to new creative heights. At this time, great masters appear, whose work will serve as a model for artists for centuries. The first of them was Leonardo da Vinci, one of the great geniuses of all time. He was the finest example of a multidisciplinary, intellectual artist obsessed with perfection, which led him to leave many unfinished or projected works. Little prolific in his pictorial facet, he nonetheless contributed many innovations that led the history of painting in new directions. Perhaps his main contribution was sfumato or chiaroscuro, a delicate gradation of light that gives his paintings a great naturalness, while helping to create space. He carefully studied the composition of his works, as in the Last Supper , where the figures conform to a geometric scheme. In his work, he knew how to unite formal perfection with certain doses of mystery, present, for example, in the famous Gioconda , The Virgin of the Rocks or the Saint John the Baptist .

Michelangelo is, chronologically, the second great figure. Fundamentally a sculptor, he dedicated himself to painting sporadically, at the request of some admirers of his work, especially Pope Julius II. The frescoes in the Sistine Chapel show the tormented inner world of this artist, populated by monumental figures, solid and three-dimensional as if they were sculptures, and striking physical presence. In his work, the nude is very important, even though almost all of it was made to decorate churches.

Rafael Sanzio completes the triad of geniuses of classicism. His style was enormously successful and became fashionable among the powerful. Raphael's painting sought above all grazia, or balanced and serene beauty. His madonnas reflect Leonardo's novelties in terms of composition and chiaroscuro, adding a characteristic sweetness. He clearly anticipated Mannerist painting in his later works, whose agitated and dramatic style was copied and disseminated by his disciples.

With the appearance of these three great masters, contemporary artists assume that art has reached its culmination —a concept reflected in the work of Giorgio Vasari The Lives— and therefore strive to incorporate these achievements, on the one hand, and in the search for their own original style as a way to overcome them. Both of these things, along with the pessimistic atmosphere that was felt in Christianity in the 1520s (Sack of Rome, Protestant Reformation, wars), gave rise to a new current, Mannerism, with force from the 1530s. From then on, the extravagant, the strange, the exaggerated and the unreal would be sought. Jacopo Pontormo, Bronzino, Parmigianino, Rosso Fiorentino or Francesco Salviati belong to this pictorial current. Other authors would take some mannerist novelties but following a more personal and classicist line. Among them we can mention Sebastiano del Piombo, Correggio, Andrea del Sarto or Federico Barocci.

Among the different schools that emerged in Italy in the Cinquecento, the one in Venice presents special characteristics. If the Florentines emphasized disegno, that is, composition and line, Venetian painters would focus on colour. The special characteristics of the Venetian state may explain some of this particularity, since it was an elitist society, lover of luxury and closely related to the Orient. The Venetian school would reflect this through a refined, hedonistic painting, less intellectual and more vital, highly decorative and colourful. Precursors of the Venetian school of the Cinquecento were Giovanni Bellini and, above all, Giorgione, a painter of allegories, landscapes and religious, melancholic and mysterious subjects. A debtor to his style was Titian, the greatest painter of this school, an excellent portrait painter, perhaps the most in demand of his time; author of complex and realistic religious compositions, full of life and color. In the last stage of his life, he undoes the contours of the figures, turning his paintings into pure sensations of light and color, an anticipation of Impressionism. Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese and Palma the Elder continued this school, leading it towards mannerism and anticipating in a certain way baroque painting.

Sculpture

As in other artistic manifestations, the ideals of returning to antiquity, inspiration in nature, anthropocentric humanism and idealism were what characterized the sculpture of this period. The Gothic had already preluded in a certain way some of these aspects, but some archaeological finds (the Laocoonte, found in 1506, or the Torso Belvedere) that occurred at the time They were a real shock for the sculptors and served as a model and inspiration for new achievements.

Although religious works continued to be made, there is a clear profane air in them; the nude and a strong interest in anatomy were reintroduced, and new technical and formal typologies appeared, such as the stiacciato relief (high relief with very little protrusion, almost flat) and the tondo, or disk-shaped composition; iconography was also renewed with mythological, allegorical and heroic themes. An unusual interest in perspective appeared, derived from contemporary architectural research, and it was reflected in reliefs, altarpieces, tombs and sculptural groups. During the Renaissance, the traditional polychrome wood carving declined somewhat in favor of stone sculpture —preferably marble— and monumental bronze sculpture, which fell into disuse during the Middle Ages, was recovered. The Florence workshops were the most renowned in Europe in this technique, and they supplied all of Europe with statues of this material.

The two centuries that the Renaissance lasted in Italy gave rise, as in the other arts, to two stages:

- The QuattrocentoXV): the main sculptural center was Florence, where the Medici family and, subsequently, the Republic, exercised tens of numerous works. Lorenzo the Magnificent was fond of Greek and Roman sculptures and had formed an interesting collection of them, fashioning the classic taste. The most outstanding authors of the time were Lorenzo Ghiberti (Puerta del Paraíso del Baptisterio de Florence), Andrea Verrocchio (Monument to Condotier Colleoni), Donatello, the workshop of the brothers Della Robbia — who introduced glazed and polychrome ceramic as a novelty, using it in decorations of buildings—, Jacopo della Quercia, Desiderio da Settignano and Bernardo Rossellino. The most important of them is Donatello, a great creator who, based on the assumptions of Gothic, established a new ideal inspired by classical grandeur. His is the merit of rescuing the public memorial — his Condotiero Gattamelata is one of the first equestrian bronze statues since ancient times—the heroic use of the nude (David) and the intense humanization of the figures, reaching the portrait at times, but without ever abandoning a clearly idealistic orientation.

- The 50th centuryXVI): this time is marked by the star appearance of one of the greatest sculptors of all time, Michelangelo. To this point he marked the sculpture of the whole century that many of his followers were not able to collect all his novelties and these were not developed until several centuries later. Michelangelo was, like so many others at this time, a multidisciplinary artist. However, he was considered preferably sculptor. In his first works he collects the archaeological interest that emerged in Florence: Coat drunk was made with the intention that it would appear to be a classic sculpture. The same spirit is appreciated in the Pityfrom 1498 to 1499 for the Vatican Basilica. Protected first by the Medicis, for those who created the Drug tombsHe then went to Rome, where he collaborated in the construction work of the new basilica. The pontiff Julio II took him under his protection and entrusted him with the creation of his Mausoleum, called by the artist as "the tragedy of the tomb" for the changes and delays that the project suffered. In the sculptures made for this tomb, like the famous Moses, appears what has been called terribilitá miguelangelesca: an intense at the same time contained emotion that manifests itself in suffering, exaggerated and nervous anatomies — muscles in tension—, contorted postures and scruples. Faces, however, tend to show content. In his final works the artist deludes the formal beauty of sculptures and leaves them unfinished, advancing a concept that would not return to art until the centuryXX.. Michelangelo continued with the tradition of heroic and profane public monuments that began Donatello and led her to a new dimension with her well-known DavidSculpted for Piazza della Signoria in Florence. In the final years of the centuria, Michelangelo's footprint had his replicas in Benvenuto Cellini (Perseus of the Loggia dei Lanzi of Florence, space conceived as an outdoor sculpture museum), Bartolomeo Ammannati, Giambologna and Baccio Bandinelli, who would exaggerate the most superficial elements of the master's work, placing themselves fully in the Mannerist current. At this time also stands out the family saga of the Leoni, Milanese broncists at the service of the Spanish Habsburgs, authentic creators of the aulica image, a somewhat stereotypical, of these monarchs. His presence in Spain led there first hand the Renaissance novelties, extending its influence to the Baroque sculpture.

Spain

In Spain the ideological change is not as extreme as in other countries; It did not break abruptly with the medieval tradition, which is why we speak of a Spanish Renaissance that is more original and varied than in the rest of Europe. Thus, literature accepts the Italian innovations (Dante and Petrarch), but does not forget the poetry of the Cancionero and the previous tradition. As for the plastic arts, the Hispanic Renaissance mixed elements imported from Italy —where some artists came from, such as Paolo de San Leocadio, Pietro Torrigiano or Domenico Fancelli— with local tradition, and with some other influences —flamenco, for example., was very fashionable at the time due to the intense commercial and dynastic relations that linked these territories to Spain. Renaissance innovations arrived in Spain very late: until the 1520s there were no finished examples of them in artistic manifestations, and such examples are scattered and in the minority. Thus, the echoes of the Italian Quattrocento did not fully reach Spain — only through the work of the Borja family did artists and works from that period appear in the Levantine area — which caused Spanish Renaissance art to pass almost abruptly from Gothic to Mannerism.

In the field of architecture, three periods are traditionally distinguished: Plateresque (15th century-first quarter of the XVI), purism or Italianate style (first half of the XVI) and Herreriano style (from 1559-mid of the following century). In the first of them, the renaissance appears superficially, in the decoration of the facades, while the structure of the buildings continues to be Gothic in most cases. The most characteristic of Plateresque is a type of small, detailed and abundant decoration, similar to the work of silversmiths, from which the name derives. The fundamental nucleus of this current was the city of Salamanca, whose University and its façade are the paradigm of the style. Outstanding architects of it were Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón and Juan de Álava. Purism represents a more advanced phase of the Italianization of architecture. The palace of Carlos V in the Alhambra in Granada, the work of Pedro de Machuca, is an example of this. The main focus of this style was located in Andalusia, where in addition to the aforementioned palace, the centers of Úbeda and Baeza and architects such as Andrés de Vandelvira and Diego de Siloé stood out. Finally, the Escurialense or Herreriano style appeared, an original adaptation of Roman mannerism characterized by nudity and architectural gigantism. The fundamental work was the palace-monastery of El Escorial, designed by Juan Bautista de Toledo and Juan de Herrera, undoubtedly the most ambitious work of the Hispanic Renaissance. What was from Escorial crossed the chronological threshold of the XVI century, reaching the Baroque era with great force.

In sculpture, the Gothic tradition maintained its hegemony for much of the 16th century. The first echoes of the new style generally correspond to artists who came from abroad, such as Felipe Vigarny or Domenico Fancelli, who worked in the service of the Catholic Monarchs, sculpting his tomb (1517). However, local artists soon emerged who assimilated the Italian novelties, adapting them to the Hispanic taste, such as Bartolomé Ordóñez and Damián Forment. In a more mature phase of the style, great figures emerged, creators of a peculiar mannerism that laid the foundations for later Baroque sculpture: Juan de Juni and Alonso Berruguete are the most prominent.

Spanish Renaissance painting is also determined by the pulse that the Gothic heritage maintains with the new modes coming from Italy. This dichotomy can be appreciated in the work of Pedro Berruguete, who worked in Urbino at the service of Federico de Montefeltro, and Alejo Fernández. Subsequently, artists familiar with contemporary Italian novelties appeared, such as Vicente Macip or his son Juan de Juanes —influenced by Rafael—, Luis de Morales, Juan Fernández de Navarrete or the Leonardesque Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina and Hernando de los Llanos. A great figure of the Spanish Renaissance, and one of the most original painters in history, he is already part of Mannerism, although exceeding its limits by creating his own stylistic universe: El Greco.

France

In France, Italian influence was felt very early, favored by its geographical proximity, commercial ties and the monarchy, which aspired to annex the bordering territories of the Italian peninsula, and succeeded at times. However, the definitive impetus for the adoption of Renaissance forms came under the reign of Francisco I. This monarch, a great patron of the arts and fond of everything that came from Italy, protected important masters, requesting their services for the French court—including Leonardo da Vinci himself, who died in the Château de Cloux—while undertaking an ambitious program of cultural revitalization that revolutionized the development of the arts in the country. It should be kept in mind that France was the cradle of the Gothic and that, therefore, this style was deeply rooted and could be seen as a national style. Hence, the Gothic forms continued to be present for a while, despite the new style imposed by the court.

As for architecture, the monarchy, strengthened and in a period of territorial expansion, had already sponsored the 15th century the remodeling of the old medieval châteaux and the creation of new residences more in keeping with the times. But it was precisely Francisco I who gave a definitive boost to this renovating operation, which had several foci. The first Renaissance building in France was the castle of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, an imposing brick and stone fortress in which small Renaissance details appear, within a general sobriety with a military air. The castles of the Loire Valley were of a more advanced style, a group of mansions for royalty and the nobility that show the most characteristic features of the French Renaissance: decorativism with Mannerist roots, Gothic memories in the structures, and perhaps the most innovative: a perfect integration of the buildings into the surrounding nature, as seen in the Château de Montsoreau or the graceful bridge of the Château de Chenonceau. The most famous within this set is the castle of Chambord, which presents great stylistic audacity, such as an internal helicoidal staircase. Other examples of these suburban residences are the castles of Amboise, Blois and Azay-le-Rideau.

In addition to all these achievements, Francisco I embarked on what was perhaps the fundamental work of this period: the Palace of Fontainebleau, an old mansion of the French kings that was completely renovated. In the building itself, the triumph of Italian forms can already be appreciated, although adapted to French taste with its typical chimneys and mansards. It includes fragments of overflowing creativity, such as the famous Imperial Staircase, a preview of baroque solutions. However, perhaps the most outstanding aspect of the project was that it involved creators from practically all artistic disciplines, some expressly coming from Italy, such as the painters Francesco Primaticcio or Rosso Fiorentino, the famous sculptor Benvenuto Cellini or the architect Sebastiano Serlio, an important author of architectural treatises of which hardly any works are known except this palace. The novelties that were forged here would cross the local sphere and give rise to a whole style, the "Fontainebleau style", a refined mannerism at the service of aristocratic tastes.

After Francis I, "Italian" forms finally prevailed definitively in architecture under Henry II, whose wife, Catherine de' Medici, belonged to the most powerful Florentine family. Under his mandate (1547-1559) the former seat of the court in Paris, the Louvre Palace, was reformed, turning it into a modern building with a fully Mannerist aesthetic. The renovation was led by one of the most prominent French architects of the time, Pierre Lescot, who designed the large central courtyard (Cour Carrée), with characteristic façades using the classic triumphal arch module Likewise, these monarchs began the construction of a new palace, opposite the Louvre, the Tuileries Palace, in which the other great French architect of the Renaissance, Philibert Delorme, intervened.

Renaissance sculpture in France was also in step with what was dictated by Italy. At the end of the XIV century, France ceased to be the great sculptural center of Europe thanks to the cathedral workshops, a situation that would continue into the 15th century, and further into the 16th century . It is paradoxical and at the same time revealing that this situation coincides with the progressive consolidation of the monarchical institution, evidently eager to renew its image and willing to use art as a first-rate propaganda instrument. Despite the loss of hegemony in this field, which in any case had never been definitive, great figures emerged in the heat of royal projects; It is noteworthy the ornamental and decorative character that the sculptures had, subordinated to the general project of the buildings and integrated into them. Two were the most outstanding authors: Germain Pilon and Jean Goujon.

Painting also experienced the progressive decline of traditional Gothic forms and the arrival of the new style. As has been pointed out, Italian pictorial forms were known first-hand in France in the XVI century thanks to the arrival of authors very innovative, like Leonardo or Rosso Fiorentino. Francisco I promoted the training of French artists under the direction of Italian masters, such as Niccolò dell'Abbate or Primaticcio, the latter being responsible for the decoration of the Palace of Fontainebleau and the organization of court festivities, and having as both at your service to many craftsmen and artists. This coexistence of talents, schools, disciplines and genres gave rise to the so-called «Fontainebleau pictorial school», a derivation of Italian pictorial mannerism that focuses on eroticism, luxury, profane themes and allegories, all very much to the taste of its main clientele, the aristocracy. Most of the Fontainebleau artists were anonymous, precisely because of the integration of the arts that was advocated and because of the teaching of established artists. However, we know the names of some painters, including Jean Cousin the Elder or Antoine Caron among the most prominent. However, the most important French painter of the time, as well as one of the great portrait painters of all time, although much of his work has been lost, was François Clouet, who surpassed his father, the equally appreciable Jean Clouet, in the faithful representation of the life of the powerful of the time, with a psychological depth and formal brilliance whose precedent must be sought in Jean Fouquet, a great painter of the century XV still in the gothic orbit.

Germany

The artistic Renaissance in Germany was not an attempt to revive classical art, but rather an intense renewal of the Germanic spirit, motivated by the Protestant Reformation. Albrecht Dürer was the dominant figure of the German Renaissance. His universal work, which was already recognized and admired throughout Europe during his lifetime, set the mark of the modern artist, uniting theoretical reflection with the decisive transition between medieval practice and Renaissance idealism. His paintings, drawings, engravings, and theoretical writings on art exerted a profound influence on 16th century artists of his own country and the Netherlands. Dürer understood the urgency of acquiring a rational knowledge of artistic production, and introduced Italian-rooted idealism into German art.

Germanic painting experienced one of its greatest moments of splendor at this time. Along with the fundamental figure of Dürer, other great authors emerged, such as Lucas Cranach the Elder, painter par excellence of the Protestant Reformation; Hans Baldung Grien, introducer of sinister and novel themes, indebted in a certain way to medieval art; Matthias Grünewald, one of the precursors of expressionism; Albrecht Altdorfer, excellent landscape designer; or Hans Holbein the Younger, who developed almost all of his production, focused on portraiture, in England.

In sculpture, Gothic forms survived well into the 16th century. The work of Peter Vischer stands out, author of the imperial tombs of Innsbruck (1513) and of the tomb of San Sebaldo in Nuremberg (1520). Some Flemish artists also worked here, such as Hubert Gerhard, author of the St. Michael on the façade of St. Michael's Church in Munich.

In architecture, the first exponents of relevance were the buildings sponsored by the Fugger family in Augsburg, such as the Fugger Chapel in the church of Santa Ana (1509-1518) or the neighborhood of workers' houses called Fuggerei (1519-1523) After the Reformation, the patronage of the German nobility focused primarily on architecture, due to its ability to show the power and prestige of the rulers. Thus, in the middle of the 16th century Heidelberg Castle was enlarged, following classical guidelines. However, most of the German princes preferred to keep the Gothic works, limiting themselves to decorating them with Renaissance ornamentation.

Flanders and the Netherlands

As the Cinquecento developed in Italy, the Flemish school of painting reached a remarkable development, as heir and continuation of the previous late Gothic tradition represented by Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden and other great masters. He was characterized by his naturalism, a trait he shares with the Italian masters, although he was reached more by experimentation than by theory or scientific advances, as in Italy. The Gothic styles survived with greater force, although nuanced with singular characteristics, such as a certain cartoonish and fantastic vein and a greater sensitivity to the reality of the common people and their customs. This interest is collected in works of a less idealized nature than the Italian ones, with a marked tendency for the almost microscopic detail that they apply to the representations —influence of the late Gothic masters already mentioned and the miniature—, and a tendency towards the decorative, without much interest. for theoretical disquisitions. On the other hand, the great contribution of Flemish art at this time was the technique of oil painting.

At the middle of the XVI century, Italian classicism entered Flemish painting with force, manifesting itself in the so-called Antwerp School and in painters like Jan van Scorel or Mabuse, some of whom remained in Italy studying the great masters. Engraving contributed greatly to the dissemination of the new models, which made the works produced in other schools and places available to practically any artist, making the Italianate style very fashionable throughout Europe. Some great names of the time were Joachim Patinir, one of the creators of landscape as an autonomous genre of painting, although still attached to Gothic; Quentin Metsys, who was inspired by Leonardo's cartoon drawings and the popular classes to portray vices and customs; the portraitist Antonio Moro; Bosco, one of the most original painters in history, formally attached to the tradition of the old Flemish school, but at the same time innovative, creator of a fantastic, almost dreamlike universe that places him as one of the precedents of surrealism (The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500-1505); and Pieter Brueghel the Elder, one of the great masters of landscape and popular customs, perhaps the most modern of them all, even though in his painting he glosses moral sentences and social criticism that have something medieval (The Triumph of Death, 1563).

In the field of sculpture, Adriaen de Vries stood out, author of expressive works —generally in bronze— in which movement, the wavy line or serpentinata and the heroic nude characterize them as excellent examples of sculptural mannerism outside of Italy.

In architecture, Gothic continued to have a great preponderance until well into the XVI century, when it was influenced by French Renaissance architecture, as denoted by the Antwerp Town Hall (1561-1565), the work of Cornelis Floris de Vriendt.

Switzerland

With the arrival of the Holbein family, Basel became the most important center of Renaissance art in Switzerland. Later, in 1661, the world's first public art collection was also founded here. One of the most important collections of Renaissance art from the Upper Rhine region is still here today. Italian influence was especially noticeable in the canton of Ticino, as evidenced in the cathedrals of San Lorenzo de Lugano (1514) and San Francis of Locarno (1528). In painting, the work of Niklaus Manuel stood out, still close to late Gothic.

Other countries

- England: in architecture, for practically the entire centuryXVI The Tudor style of Gothic origin persisted, while the Renaissance novelties were adopted only in some ornamental elements; thus, for example, in the tomb of Henry VII in the abbey of Westminster, made architecturally in the purest Gothic style, the Italian artist Pietro Torrigiano was hired to perform the sculptural decoration. Other examples of Tudor style would be the palaces of Sutton (1523), Nonsuch (1530) and Hampton Court (1514-1540). Later the Palladian influence was received, which was developed especially in the construction of palaces.

- Portugal: in architecture, the Gothic survived well into the centuryXVI in the so-called Manueline style. In the middle of the century the influence of Italian architects such as Serlio or Palladio was received, as it is denoted in the church of Our Lady of Grace in Évora (1536) or in the cloister of the convent of Christ of Tomar (1554-1562), works of Diogo de Torralva. In this country the Italian architect Filippo Terzi, author of the church of Saint Vincent de Fora in Lisbon (1582).

- Austria and Bohemia: united by the Habsburg empire, these countries had the sponsoring work of Emperor Rodolfo II, a great collector who treasured in his court in Prague a great variety of works of art and objects of all kinds (Jews, minerals, watches, automatons, scientific instruments), as he was also a great lover of science. He acquired paintings by artists such as Brueghel, Tiziano, Leone Leoni or Durero, and welcomed artists such as Giuseppe Arcimboldo, an original portrait painter made with elements of the sketches. Various palaces were built in Bohemia, such as the Pilsen Communal and Schwarzenberg in Prague; and castles, such as those of Litomyšl, Černý and Kostelec.

- Hungary: this country had the great patronage of King Matías Corvino, a great lover of Italian art, perhaps for the influence of his wife, Beatriz de Nápoles. The monarch bought numerous works of Italian art, and hired Italian artists and architects to reform and decorate their palaces, such as Benedetto da Maiano, Clemente Camicia and Giovanni Dalmata; the miniaturist Attavante degli Attavanti was the author of the Breviary of Matías Corvino and Marciano Capella Codex; the sculptor Andrea Ferracci made the altar Announcement from the cathedral of Esztergom.

- Poland: as in other countries, the Renaissance novelties came from the hand of Italian artists arrived in the country, such as the architects Franciscus Italus and Bartolomeo Berecci (Palacio Real de Cracovia), Gian Maria Mosca (Palacio Episcopal de Cracovia) and Giovanni Battista di Quadro (Palacio Municipal de Poznań) and the sculptors Santi Gucci Instead, German artists, such as Hans Sues von Kulmbach, Louz von Kitzingen and Martin Koeber, worked mostly in painting. The miniature was also significantly developed, in which the Baltasar Behem Codex and Precess book from Segismund I.

- Russia: during this time the traditional Russian architecture of Byzantine influence continued, but some influence was received from the Italian Renaissance through the Bolognese architect Aristotele Fioravanti, who traveled in 1475 to Russia invited by Ivan III, where he built the Cathedral of the Dormition in the Kremlin of Moscow (1475-1479150); another Arquitaine, Aloisio Nuovo, was also in charge of building the cathedral. The Italian influence is also noted in the Cathedral of St. Basil of Moscow, the work of Póstnik Yákovlev (1555-1560).

Hispanic American Colonial Art

The first samples of colonial architecture in America had, as in the metropolis, a certain survival of Gothic features, although the new currents that were produced in Spain soon began to arrive, such as purism and plateresque (Cathedral of Santo Domingo). At the beginning of colonization, the architecture that developed was mainly religious: by royal order, the first building to be built in any new city had to be a church. During the first half of the XVI century, religious orders were in charge of building numerous churches in Mexico, preferably a type of fortified churches, in a crenellated complex with a church, a convent, an atrium and an open chapel —called "Indian chapels"—, such as the Tepeaca Convent, the Huejotzingo Convent, and the San Gabriel Convent in Cholula. they began to build the first great cathedrals, such as those of Mexico, Puebla and Guadalajara. The rectangular floor plan with a flat front is generally followed, taking the Cathedral of Seville, Jaén and Valladolid as models. In Peru, the cathedral of Cuzco was begun in 1582 and, in 1592, that of Lima, both works by Francisco Becerra from Extremadura. In Argentina, the cathedral of Córdoba stands out, the work of the Jesuit Andrés Blanqui.

The first samples of colonial painting were those of religious scenes elaborated by anonymous masters, made with pre-Columbian means, with vegetable and mineral inks and fabrics with a rough and irregular weave. The images of the Virgin with Child stood out, with an iconography of autochthonous roots where, for example, the archangels were represented as contemporary arquebusiers. The artistic production made in New Spain by indigenous people in the XVI century is called Indo-Christian art. Late in the XVI century, large mural frescoes arose, of a popular nature. From the middle of the century, Spanish masters (Alonso Vázquez, Alonso López de Herrera), Flemish (Simon Pereyns) and Italians (Mateo Pérez de Alesio, Angelino Medoro) began to arrive from Seville.

In sculpture, the first samples were again in the religious field, in free-standing carvings and altarpieces for churches, generally made of wood covered with plaster and decorated with incarnation —direct application of color— or stew —on a background of silver and gold-. At the beginning of the XVII century the first local schools were born, such as the Quito, the Cuzco and the Chilota, highlighting the sponsorship of the jesuit order.

Graphic and decorative arts

The industrial arts had a great boom due to the taste for luxury of the new wealthy classes: cabinetmaking developed, especially in Italy and Germany, emphasizing the technique of intarsia, wooden inlays of various shades to produce effects linear or of certain images. Tapestry stood out in Flanders, with works based on sketches developed by painters such as Bernard van Orley. The ceramic was made in Italy with glazed varnishes, achieving brilliant tones with great effect. Glass developed notably in Venice (Murano), sometimes decorated with gold threads or colored glass filaments. Goldsmithing was cultivated by sculptors such as Lorenzo Ghiberti or Benvenuto Cellini, with pieces of great virtuosity and high quality, especially the enamels and cameos.

At this time the graphic arts developed remarkably, especially thanks to the invention of the printing press, appearing or perfecting most of the engraving techniques: chalcography (etching, aquatint, burin engraving, half-tone engraving or hand engraving). drypoint), linocut, woodcut, etc. Metal engraving developed in Italy, practiced especially by Florentine goldsmiths during the 15th and xvi, while in the Cinquecento etching was perfected thanks to the work of Parmigianino. In Germany, the work of Dürer, a specialist in the burin technique, stood out, although he also made woodcuts. In France, engraving was practiced by the Fontainebleau school, in which Jean Duvet, famous for his Apocalypse series (1561), stood out. In Flanders, notable engravers arose in the city of Antwerp, such as the Wierix brothers, authors of prints with excellent technique and detail, although based on compositions by others; or Hieronymus Cock, who reproduced numerous works by Brueghel.

Gardening

During the Renaissance, gardening gained special relevance, parallel to the boost given to all the arts at this time, mainly thanks to the patronage of nobles, princes and high officials of the Church. The Renaissance garden was inspired by the Roman, in aspects such as the sculptural decoration or the presence of temples, nymphaeums and ponds. The first examples arose in Florence and Rome, regions with a rugged terrain and large uneven terrain, which led to carrying out preliminary studies of an architectural nature to plan the structure of the garden, originating landscape architecture. An example of this is the Belvedere Gardens in Rome, designed by Bramante in 1503, who solved the unevenness with a system of terraces, which are accessed by wide stairs and which are surrounded by balustrades, a scheme that would become typical. of the Italian garden, which would become the prototype of the Renaissance garden. Special importance was attached to hydraulic work, with highly complex ponds and fountains, such as those of the Villa d'Este in Tivoli, designed by Bernini. These designs passed to the rest of Europe, where French gardens stand out for their magnificence, such as those of the castles of Amboise, Chambord and Villandry. In France it was customary to subdivide the garden into various specialized areas (geometric, medicinal, wild garden), as well as the construction of canals that allowed boating. At this time the custom of trimming the hedges began, appearing the first labyrinth-shaped gardens. We must also highlight the arrival of new species thanks to the discovery of America, which favored the opening of botanical gardens dedicated to the study and cataloging of plants.

Renaissance garden theory was especially nourished by Leon Battista Alberti's conception of the house and the garden as an artistic unit based on geometric shapes (De Re Aedificatoria, IX, 1443-1452), as well as in the model set forth by Francesco Colonna in his Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499), which introduced the use of flower beds and the use of topiary art to give capricious shapes to the trees, or the design of the eras from axial forms, expounded by Sebastiano Serlio in Tutte l'opere d'architettura (1538).

Literature

Renaissance literature developed around humanism, the new theory that stressed the primary role of the human being over all other considerations, especially religious ones. At this time the world of letters received a great boost with the invention of the printing press by Gutenberg, a fact that led to access to literature by a larger audience. This led to a greater concern for spelling and linguistics, with the emergence of the first grammar systems in vernacular languages (such as Elio Antonio de Nebrija's Spanish) and the appearance of the first national language academies. The participation of philologists at the time was of great help and necessity for the study, analysis and understanding of ancient texts (mainly classical) during the XV century up to the 16th century.

The new literature was inspired like art by the classical Greco-Roman tradition, although it also received a great influence from the Neoplatonic philosophy developed contemporaneously in Italy. On the other hand, it reflects the new ideal of the Renaissance man, which is exemplified in the figure of the "courtier" defined by Baldassare Castiglione: he had to master weapons and letters alike, and have "good grace" or naturalness without artifice. In its nature, the Renaissance essence is born in Italy, it is in this territory where a thought based on human dignity and freedom is born, in which, of course, a liberal thought based on educational criticism, promoting a merely formative ideal. A movement that, like the classical Paideia, would promote similar principles and values. Humanism, with its clarifying values on human value and essence, also comes to deepen and recreate the importance and need to understand classical texts, cleaning them from any stain of corruption or intentional manipulation, or from simple literal or literary misinterpretation. In this way, and with these principles, a labor and academic society arises, which is satisfied with philological work. So, in the Western Renaissance of the XV century and of the same Italian Humanism, which gives vivacity and follow-up to the critical study of Greek culture. It is therefore, that the passage of the Hellenistic culture to Italy was an enriching process both in the teaching and copying of ancient texts and manuscripts as well as the learning of the Latin and Greek languages and the same collection of texts scattered around the territory. Many of these people concerned about the spread of Hellenic literature were Planudes, Moscópulo, Magister and Demetrio Triclinio. Lorenzo Valla and his emendationes in translation marked a before and after in the understanding between Herodotus and Thucidides. Erasmus of Rotterdam, also recognized as one of the best textual critics of the modern era, analyzed the Holy Scriptures and the classical texts through him, so that he published translations of Aristotle, Democritus, and John Chrysostom. (Morocho, pages 4-9)

With the passage of time the importance of the critical activity of Greco-Roman texts is increasing. Its importance can be associated with the need to understand historical aspects, natural sciences, geography, astronomy, and many more. Thus, philological work is booming and has unparalleled importance. Despite the ecclesiastical intervention, mentioning those who correct or work with non-religious texts, commit heresy and sin.

In Italy, the cradle of the new style, there were still echoes of three great medieval authors sometimes considered precursors of the new movement: Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio. Among the writers that emerged in this era, it is worth highlighting: Angelo Poliziano, Matteo Maria Boiardo, Ludovico Ariosto, Jacopo Sannazaro, Pietro Bembo, Baldassare Castiglione, Torquato Tasso, Nicholas Machiavelli and Pietro Aretino. Its influence was denoted in France, where François Rabelais, Pierre de Ronsard, Michel de Montaigne and Joachim du Bellay developed. In Germany, the Protestant Reformation imposed greater austerity and a religious theme, cultivated by Ulrich von Hutten, Sebastian Brant and Hans Sachs. In England, it is worth mentioning Thomas More, Edmund Spenser, Michael Drayton, Henry Constable, George Chapman, Henry Howard and Thomas Wyatt. In Portugal there is the predominant figure of Luís de Camões.

But something that can be affirmed is that Italy, in its Renaissance heyday, was certainly the cradle of humanism, therefore of the Western Renaissance itself. Therefore, more than a commercial city or country, it is a living museum, in which a cultural richness and a historically fecund heyday unfold. since it is well known that Rome, the Italian capital, was in its glory days the capital of the Roman Empire. For this reason the formation and naturalization of Latin has not been something new.

Against the Catholic clergy and the papacy, textual criticism has a very strong tributary, whose scholarly need and literal perception is vital for understanding what happens in antiquity. Contribution that can be associated, according to Quirós, (1994) to the Byzantines, who brought with them a significant number of Greek manuscripts to the Italian territory. At the same time, Francesco Petrarca, as previously mentioned, has fostered the critical spirit and the literary value of classical authors and texts. It is concluded, being more than clear, that the humanism born in Italy will be the founder and promoter of critical thinking and the one that will be in charge of vindicating the value of Greek culture.

A golden age of letters began in Spain, which would last until the XVII century: poetry, influenced by the Italian stil nuovo, featured the figures of Garcilaso de la Vega, Fray Luis de León, Saint John of the Cross and Saint Teresa of Jesus; books of chivalry arose in prose (Amadís de Gaula, 1508) and the picaresque genre began with Lazarillo de Tormes (1554), while the work of of Miguel de Cervantes, the great genius of Spanish letters, author of the immortal Don Quixote (1605).

On the other hand, the Spanish Renaissance (initiated or promoted by the arrival of Antonio de Nebrija and accepted by the kings of Spain themselves), clearly has an ethical line based on Italian thought, which before starting the studies and approaches of the Greco-Romance, incorporate Italian literary teaching models. (Dante, Boccaccio, Petrarch). The few philologists of the time used the valuation of texts based on their antiquity and greater veracity and quality of reading. Thus, as Nebrija's Apology affirms, the germana lectio should not be directed towards the consensus codicum, but always focused on the quality of the reading. (Morocho, p. 10)

Now, as mentioned above, with the contributions of Antonio de Nebrija, he begins one of the greatest Spanish philological works. The translation of texts from Latin to Romance. He works that is possible since one of the manifestations of the Spanish Renaissance consisted of the recovery of Latin writings, litterae humanitas on Ciceronian works. That, under the rule of Cicero, and by imitatio and emulatio, in consortium with the thought of Lorenzo Valla, Castilian grammar was born, coming from Latin.

Theater

Renaissance theater also suffered the transition from theocentrism to anthropocentrism, with more naturalistic works, with a historical aspect, trying to reflect things as they are. The recovery of reality was sought, of life in movement, of the human figure in space, in three dimensions, creating spaces with illusionistic effects, in trompe-l'œil. Theatrical regulations based on three units (action, space and time) emerged, based on Aristotle's Poetics, a theory introduced by Lodovico Castelvetro. Around 1520 the Commedia dell'arte arose in northern Italy, with improvised texts, in dialect, mime predominating and introducing archetypal characters such as Harlequin, Colombina, Pulcinella (called in France Guignol), Pierrot, Pantalone, Pagliaccio, etc. The main playwrights included Niccolò Machiavelli, Pietro Aretino, Bartolomé Torres Naharro, Lope de Rueda and Fernando de Rojas, with their great work La Celestina (1499). Elizabethan theater stood out in England, with authors such as Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, Thomas Kyd and, especially, William Shakespeare, a great universal genius of letters (Romeo and Juliet, 1597; Hamlet, 1603; Othello, 1603; Macbeth, 1606).

Music

Renaissance music was the consecration of polyphony, as well as the consolidation of instrumental music, which would evolve towards the modern orchestra. The madrigal appeared as a secular genre that combined text and music, being the paradigmatic expression of Renaissance music. In 1498 Ottaviano Petrucci devised a printing system adapted to music, on staff, with which music began to be published. The first innovations occurred in Flanders, where the so-called “flamenco” polyphony was developed, cultivated by Guillaume Dufay, Johannes Ockeghem and Josquin des Prés. Orlandus Lassus, Luca Marenzio, Carlo Gesualdo, Claudio Monteverdi, Cristóbal de Morales and Tomás Luis de Victoria also cultivated the madrigal, while Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina excelled in religious polyphony. In instrumental music, Giovanni Gabrieli excelled, who experimented with various timbres of wind instruments and with crossover and relief sound effects.

In Protestant countries, music gained great relevance, since Luther himself defended the importance of music in religious liturgy. Here the choir was especially cultivated, a musical genre a capella or with instrumental accompaniment, generally for four mixed voices. Some of the composers who cultivated it were Johann Walther and Valentin Bapst.

At the end of the XVI century, opera was born, the initiative of a circle of scholars (the Camerata Fiorentina) who, upon discovering that ancient Greek theater was sung, had the idea of setting dramatic texts to music. The first opera was Dafne (1594), by Jacopo Peri, followed by Euridice (1600), by the same author; in 1602 Giulio Caccini wrote another Euridice; and, in 1607, Claudio Monteverdi composed La favola d'Orfeo, where he added a musical introduction that he called the sinphony, and divided the sung structures into arias .

Dance

Renaissance dance had a great revitalization, due again to the preponderant role of the human being over religion, in such a way that many authors consider this period the birth of modern dance. It developed mainly in France –where it was called ballet-comique–, in the form of danced stories, based on classical mythological texts, being promoted mainly by Queen Catherine de Médicis. The first ballet is usually considered to be the Ballet comique de la Reine Louise (1581), by Balthazar de Beaujoyeulx. The main modalities of the time were the gallarda, the pavana and the tourdion. The first treatises on dance appeared at this time: Domenico da Piacenza wrote De arte saltandi et choreas ducendi, being considered the first choreographer in history; Thoinot Arbeau made a compilation of French folk dances (Orchesographie, 1588).

Philosophy

Renaissance philosophy was originally marked by the decline of theology, in a world doomed to modernity that, without yet renouncing religion, limited it to the spiritual and personal sphere of the individual. The new way of dealing with the problems of the human being will be rationalism, the use of reason applied to society and nature. Even so, religion continued to be present to a large extent during this time, although it derived from scholastic theology towards the mysticism, towards a relationship with God based more on feeling than on knowledge, as well as on action, the work of approaching God, as seen in the work of Jan van Ruusbroec, Dionisio Cartujano and Tomás de Kempis.

The new current of these times will be humanism, more interested in man and nature than in divine and spiritual issues. Naturalism pervades all areas of knowledge, and thus one speaks not only of natural science, but also of natural law, natural morality, and even natural religion, a religion that abandons everything supernatural (revelation, dogma) to be a faithful reflection of the position of the human being in the world. Humanism is based, like art, on the opposition to medieval culture and the return to classical antiquity; However, a good part of Renaissance philosophy evolved from medieval philosophy in a continuous line that reaches Descartes. It was not for nothing that medieval scholasticism was based on Platonic and Aristotelian Greek philosophy. Even so, numerous humanists despised scholastic Aristotelianism for being excessively theologized, and they approached Plato from the work of his later followers, the so-called Neoplatonism, especially from the field of Stoic philosophy that, like the Renaissance, had a more special impact on the human being as the measure of all things. However, many of these authors approached the subject from a superficial and not very rigorous position, without delving into the ontological and metaphysical aspects of the Greek classics, without analyzing the new intellectual situation of the human being distanced from God, an issue that will not reach until the present day. Cartesianism.