Refracting telescope

A refracting telescope is a focused optical system, which captures images of distant objects using a set of lenses in which light is refracted. The refraction of light in the objective lens causes parallel rays, coming from a very distant object (at infinity), to converge on a point on the focal plane. This makes it possible to display the brightest and largest distant objects.

These types of telescopes are very common in amateur astronomy and some solar telescopes (for which filters are used), and for almost 300 years (between about 1600 and 1900) they became the main type of measuring instrument. work of the most outstanding observatories in the world. However, there are important technical difficulties that prevent the realization of refracting telescopes of large dimensions and large aperture, since it is difficult to make useful lenses that are large and light enough to be used as objectives. On the other hand, there are image quality problems due to small air bubbles trapped in the glass of the main lens, and also, the lens material is opaque at certain wavelengths, so sensitivity is lost at some parts of the light spectrum. Most of these problems are solved using a reflecting telescope.

The problem of chromatic aberrations is partially corrected with apochromatic lenses, although this type of telescope is expensive.

Historical overview

The refracting telescope was the first type of optical telescope and its invention cannot be precisely attributed. Some writings suggest that a prototype had been developed in the 1550s, but the first explicitly described examples come from Italy (1590) and Northern Europe (the Netherlands, around 1608). Giambattista della Porta mentions it in his book La Magie naturelle (1589). Subsequently, several people tried to obtain a patent: Hans Lippershey, who first made a concrete demonstration of one at 3x magnification in late September 1608; Zacharias Janssen, who made an instrument that he reportedly sold at the autumn fair in Frankfurt in September 1608; and Jacob Metius of Alkmaar. The latter is supported by Descartes, who speaks in 1637 of this invention at the beginning of his Dioptrique:

But, to the shame of our sciences, this invention, so useful and admirable, has not been first found more than by experience and fortune. About thirty years ago, a man named Jacques Metius of the city of Alkmaar in the Netherlands, a man who had never studied, even though he had a father and a brother who made a profession of mathematics, but who had a special pleasure in making thick mirrors and bright lenses, composing them even in winter with the ice, so the experience has shown that it can be done, having on this occasion several glasses of different forms, thought byMais, à la honte de nos sciences, cette invention, si utile et si admirable, n'a premièrement été trouvée que par l'expérience et la fortune. Illustration:Dioptrique (1637), René Descartes

Once the telescope became known and spread, several people, including Thomas Harriot and Christoph Scheiner, turned it skyward in early 1609 to observe celestial objects. But it was Galileo Galilei who, from August 1609, really established the telescope as an instrument of astronomical observation for all his celestial discoveries and, especially, for the new look that he took to the sky and the objects he contemplated, marveling at the phenomena that he saw and studied. Galileo, while in Venice around the month of May, had found out about the invention and had built his own version. He then communicated the details of his invention in public and presented his own instrument to the Doge Leonardo Donato in a session before the council. He built his own lenses and initially gave them a magnification of six instead of three, gradually increasing to 20 and then 30.

The earliest known depiction of a telescope is a work by Jan Bruegel the Elder, Paysage sur le château de Mariemont, in which Archduke Albert of Habsburg holds the instrument.

According to some researchers, the person who supposedly invented the telescope was the Catalan optician Juan Roget in 1590, whose invention would have been copied by Zacharias Janssen.

Following Galileo's pioneering designs, as more and more powerful telescopes were built, the problem of chromatic aberration was a severe limiting factor in their image quality. To avoid this problem, Keplerian telescopes designed with enormous focal lengths were developed, a factor that made them very unwieldy. These limitations of refracting telescopes led to the first development of mirror telescopes, which by the end of the 18th century had reached considerable advance by the hand of William Herschel.

However, the progress of achromatic lens design by John Dollond during the 18th century, put the foundations of the era of large refractors, which began in 1820 with the first 9-inch achromatic refracting telescope built by Joseph von Fraunhofer for the Dorpat Observatory in Estonia. The maintenance problems of the metallic mirrors of the time made refracting instruments once again the favorites of astronomers.

Throughout the XIX century, numerous observatories were founded throughout the world (both state and private), who competed to have the best telescope, which resulted in a "race" for manufacturing lenses of greater diameter each time. Thus, in the 80 years between 1820 and 1900, the Fraunhofer telescope went from the 22.8 cm diameter to the 125 cm Telescope of the Great Universal Exhibition in Paris (1900), with which the technical limit of refractors, conditioned by manufacturing difficulties and the problem of sagging of the lenses.

During this period, a handful of notable builders built their reputations with ambitious achievements, such as G. & S. Merz (company that continued the work of Fraunhofer); John Brashear; Carl Zeiss; the Henry brothers; or Alvan Clark & Sons (manufacturer in 1897 of the largest lens still in service, that of the Yerkes Observatory telescope, with a 102 cm diameter).

Despite the rise of reflecting telescopes during the 20th century (thanks first to improved silver-plating techniques of mirrors at the end of the XIX century, and later the development of segmented mirror techniques supported by the advancement of computers), achievements such as the 98 cm diameter refracting telescope at the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory, inaugurated in 2002, confirm that this type of instrument continues to be valid for certain astronomical tasks, such as solar observation.

Refracting telescope designs

All refracting telescopes use the same principles. The combination of objective lens and some type of eyepiece is used to gather more light than the human eye is capable of gathering on its own, to present the viewer with a magnified virtual image that is brighter and clearer.

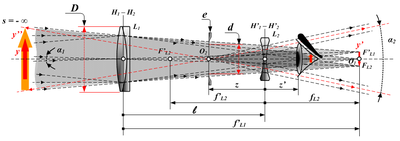

The objective in a refracting telescope is used for light rays parallel to the axis of the instrument subjected to the physical phenomenon of refraction to converge on a focal point; while non-parallels converge in a focal plane. The telescope converts a bundle of parallel rays that make an angle α with its optical axis into a second parallel beam with an angle β. The ratio β/α is called the angular magnification. It is equal to the ratio between the image sizes on the retina obtained with and without the telescope.

Refracting telescopes can adopt many different configurations to correct for image orientation and types of aberration. Because the image is formed by bending light, or refracting it, these optical instruments are called "refracting telescopes" or simply "refractors".

Galilean telescope

Galileo Galilei's design used in 1609 is commonly called the Galilean telescope. He used a converging lens in the objective (plano-convex) and a diverging lens (plano-concave) in the eyepiece (Galileo, 1610).A Galilean telescope, since the design has no intermediate focus, gives rise to a non-image. inverted and upright.

Galileo's best telescope achieved a magnification of 30 times. Due to design flaws, such as the shape of the lens and the narrow field of view, images were blurred and distorted. Despite these flaws, the telescope was still good enough for Galileo to explore the sky. The Galilean telescope could detect the phases of Venus, and was able to see craters on the Moon and four moons orbiting Jupiter.

Parallel rays of light from a distant object (y) are brought to a point in the focal plane of the objective (F' L1 / y'). The (diverging) lens of the eyepiece (L2) intercepts these rays and makes them parallel once more. Non-parallel light rays from the object traveling at an angle α1 to the optical axis travel at a larger angle (α2>α1) after passing through through the eyepiece. This leads to an increase in apparent angular size and is responsible for the perceived magnification.

The final image (y') is a virtual image, located at infinity and with the same shape as the object.

Keplerian telescope

The arrow in (4) is a schematic representation of the original image; the arrow in (5) is the image inverted in the focal plane; the arrow in (6) is the virtual image that forms in the visual sphere of the viewer. Red rays produce the midpoint of the arrow; two other sets of rays (in black) produce the head and tail.

The Keplerian telescope, invented by Johannes Kepler in 1611, is an improvement on Galileo's design. It uses a convex lens in the eyepiece instead of the concave one of Galileo's model. The advantage of this arrangement is that the light rays emerging from the eyepiece are converging. This allows for a much wider field of view and greater detail, but the image to the viewer is reversed. Considerably higher magnifications can be achieved with this design, but to overcome aberrations, the simple objective lens needs to have a very high f focal ratio (Johannes Hevelius built instruments with a focal length of 46m, and even " "tubeless aerial telescopes" with greater distances). The design also allows for the use of a micrometer at the focal plane (used to determine angular size and/or distance to observed objects).

Achromatic Refractors

The achromatic refractive lens was invented in 1733 by an English lawyer named Chester Moore Hall, though it was independently invented and patented by John Dollond around 1758. The design overcame the need for very long focal lengths in refracting telescopes using an objective made with two pieces of glass with different dispersion indices, "crown glass" and "flint glass", limiting the effects of chromatic aberration and spherical aberration. The two sides of each piece are ground and polished, and then the two pieces are assembled together. Achromatic lenses are designed so that two wavelengths (typically red and blue) are focused in the same plane. The era of large refractors in the 19th century saw the manufacture of enormous achromatic lenses, culminating in the largest achromatic refractor ever built, the Telescope of the Great Universal Exhibition in Paris (1900), in which a 125 cm diameter lens was used.

Apochromatic Refractors

Apochromatic refractors have objectives made of special materials with extraordinarily low dispersion. They are designed to focus three wavelengths (typically red, green, and blue) into the same plane. The residual color error (tertiary spectrum) can be up to an order of magnitude less than that of an achromatic lens. Such telescopes contain fluorite elements or special extra-low dispersion (ED) glass in the objective and produce a razor-sharp image that is virtually free of chromatic aberration. Due to the special materials required in manufacturing, apochromatic refractors are generally more expensive than telescopes of other types with a comparable aperture.