Ray

Lightning is a powerful natural discharge of static electricity, produced during an electrical storm, generating an electromagnetic pulse. The precipitated electrical discharge of lightning is accompanied by the emission of light (lightning).

On average, lightning is 1500 meters long; the longest was recorded in Texas and reached 190 km in length. Lightning can reach the speed of 200,000 km/h. It is always accompanied by lightning (intense emission of electromagnetic radiation, whose components are located in the visible part of the spectrum), and thunder (emission of sound waves), in addition to other associated phenomena. Although intracloud and intercloud discharges are the most frequent, cloud-to-ground discharges pose a greater danger to humans. Most of the lightning strikes occur in the tropical zone of the planet, the most densely populated, and mainly on the continents. They are associated with convective phenomena, most often thunderstorms, although they may be caused by other events, such as volcanic eruptions, nuclear explosions, sandstorms, or violent forest fires. Artificial methods are used to create lightning for purposes scientists. Lightning also occurs on other planets in the Solar System, particularly Jupiter and Saturn.

Some scientific theories consider that these electrical discharges may have been fundamental in the emergence of life, as well as having contributed to its maintenance. In the history of humanity, lightning was perhaps the first source of fire, essential for technical development. Thus, lightning aroused fascination, joining countless legends and myths that represent the power of the gods. Subsequent scientific investigations revealed their electrical nature, and since then the discharges have been the subject of constant surveillance, due to their relationship with storm systems.

Due to the great intensity of the voltages and electric currents that it propagates, lightning is always dangerous. Thus, buildings and electrical networks need lightning rods and protection systems. However, even with those protections, lightning still causes deaths and injuries around the world.

How the electrical discharge is initiated remains a matter of debate. Scientists have studied the root causes, which range from atmospheric disturbances (wind, humidity, and pressure) to the effects of the solar wind and solar particle accretion charged. Ice is believed to be the key component in development, promoting a separation of positive and negative charges within the cloud. As a high-energy phenomenon, lightning generally manifests along an extremely bright path — in the plasmatic state, a consequence of the ionization of the air due to the very high tensions— which travels long distances, sometimes with branches. However, there are rare forms, such as ball lightning, whose nature is unknown. The large variation in the electric field caused by discharges in the troposphere can give rise to transient light phenomena in the upper atmosphere.

Every year there are 16,000,000 lightning storms recorded.[citation needed] The frequency of lightning is approximately 44 (± 5) times per second, or almost 1.4 billion flashes per year, with the average duration being 0.2 seconds. The longest duration lightning was recorded in March 2018 in the north from Argentina and lasted 16.73 seconds. In October 2018, the longest horizontal extension in the world was recorded in Brazil, with 709 km in length. Lightning travels at an average speed of 440 km/s, being able to reach speeds of up to 1400 km/s. The potential difference average relative to the ground is one billion volts.

The discipline that, within meteorology, studies everything related to lightning is called ceraunology.

History

Lightning probably appeared on Earth long before life, more than 3 billion years ago. In addition, lightning was probably essential for the formation of the first organic molecules, essential for the appearance of the first forms of life. Since the beginning of history, lightning has fascinated humans. The fire that lightning produces when it hits the ground would have been the source of their domestication, and would be used to keep them warm at night, as well as keep wild animals away. Primitive man would then have searched for answers to explain this phenomenon, creating superstitions and myths that were incorporated into the oldest religions.

Biological Significance

From biology it is believed that lightning played an important role in the appearance of life on Earth. Through different experiments such as the Miller-Urey one, it was shown that, in a primitive atmosphere, electrical discharges could have generated the necessary reactions to create the first molecules of life and the bases that make it up, such as Amino Acids (molecules fundamental in all biological systems).

Scientific Research

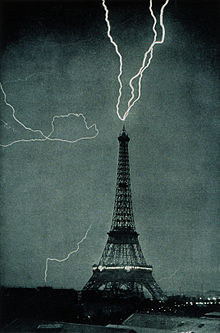

In modern European cultures, the first known scientific explanation was written by the Greek philosopher Aristotle, in the [[4th century] century a. C.]], attributing the storm to the collision between two clouds and the lightning to the fire exhaled by those clouds. However, the first systematic studies were not carried out until 1752, at Marly-la-Ville, near Paris., when Thomas-François Dalibard attracted lightning by means of a high iron rod isolated from the ground by glass bottles. This experiment demonstrated the electrical nature of the discharge. Subsequently, numerous tests were carried out. One of the best known is that of Benjamin Franklin, who used kites and balloons to lift conductive wires, which generated small lightning bolts thanks to the electric field existing in the clouds.

Franklin also showed that lightning manifested "most often in the negative form of electricity, but sometimes it appears in the positive form." In addition, the scientist proposed the use of large metal rods to protect against lightning strikes, which, according to him, would silently pass electricity from the cloud to the ground. Later, he realized that these rods did not influence the electrical charges present in the clouds, but actually attracted lightning. He eventually realized that while electrical discharges could not be avoided, he could at least attract them to a point where there would be no danger, known as a lightning rod. To demonstrate the effectiveness of his ideas, Franklin gathered hundreds of people near Siena, Italy, in 1777, in a place often struck by lightning. After the lightning rod was installed, the crowd watched as the lightning struck the metal bar, without damaging it.

In 1876, James Clerk Maxwell proposed creating magazines for black powder that were completely encased in a layer of metal to prevent lightning from detonating the compound. When lightning struck that shell, the electrical current remained in that outer layer and did not reach the gunpowder. This system is now known as a Faraday cage. A grid system can also be used; however, the greater the distance between conductors, the less effective the protection will be. Combinations between the Franklin lightning rod and the Faraday box are still used in the XXI century to protect buildings, especially where they are located. sensitive electronic devices.

The appearance of photography and spectroscopy at the end of the XIX century were of great importance in the study of good heavens. Various scientists used the spectrum generated by lightning to estimate the amount of energy involved in the physical process taking place over a very short period of time. The use of the photographic camera also made it possible to discover that lightning has two or more electrical flows. The development of new devices in the 20th century, such as oscilloscopes and electromagnetic field meters, allows a more complete understanding of the origin and occurrence of discharges.

Features

Lightning, which is most commonly associated with thunderstorms, is a gigantic electrical arc of static electricity through which a conductive channel is formed and electrical charges are transferred. There are several types of lightning that can occur: inside the clouds themselves, between two clouds, between a cloud and the air, and between a cloud and the ground. The points of contact of lightning depend on the way in which electrical charges are distributed inside the clouds. In general, the distribution of charges in convective clouds generates a strong electric field. In the upper part of the cloud, which is flattened and extends horizontally, positive charges accumulate in small ice crystals from convection currents. In the center, usually in a range where the temperature is between -20 and −10 °C, negative charges are in overabundance. The dipoles formed are each worth tens of coulombs, separated from each other by a few kilometers vertically. A small region of positive charges usually forms at the base of the cloud, the charge of which is only a few coulombs. In more developed storms, the electrical distribution is much more complex..

Charge of the clouds

For an electric discharge to occur, the interior of the cloud must have an important electric field, which arises from the change in the distribution of charges, electrifying the cloud. It is not known exactly how this phenomenon occurs, although some basic concepts and premises have been theorized. The electrification models are divided into two, the convective and the collider.

According to the convective electrification model, the initial electric charges come from a pre-existing electric field before the development of the thundercloud. As the thundercloud develops, positive ions accumulate inside the cloud, inducing negative charges at its edges. As the winds within the cloud are ascending, air currents from the opposite direction appear at the edges of the cloud, carrying the induced negative charges to the cloud base, thus creating two electrically distinct regions. As the process unfolds, the cloud becomes capable of attracting new charges of its own, allowing electrical discharges to appear. Although it demonstrates the importance of convection in the electrification process, this model does not satisfactorily describe the load distribution at the onset of the storm and in the long term.

The collisional electrification model, as its name suggests, assumes that the charge transfer takes place with the contact between the cloud particles during the convection process. However, there is no consensus on how polarization and charge separation occur in the tiny ice particles. Theories are divided into two classes, the inductive (depending on a pre-existing electric field) and the non-inductive.

In the inductive hypothesis, the pre-existing electric field, which points downward under normal conditions, causes the appearance of positive charges in the lower part and negative charges in the opposite region. The separation of the charges seems to require a strong updraft to carry the water droplets upward, supercooling them between –10 and –20 °C. The particles have different sizes, so the heavier ones tend to fall while the lighter ones are carried by convective winds. The contact of the smaller particles with the lower hemisphere of the larger ones causes the transfer of charges, the lighter one with a positive charge and the heavier one negatively charged. Collisions with ice crystals form a water-ice combination called hail and gravity causes the heavier (and negatively charged) being to fall towards the center and lower parts of the clouds. As the cloud grows, negative charges accumulate at its base and positive charges at its top, increasingly intensifying the electric field and the particle polarization process to the point of producing lattices with potential differences until they become enough to start a download. The non-inductive electrification hypothesis, on the other hand, is based on the generation of charges from the collision between particles with different intrinsic properties. Snow granules (spherical particles smaller than hail) and small ice crystals, when they collide, acquire opposite charges. The first, heaviest, carry negative charges, while the crystals reach the top of the cloud, which is therefore positively charged. For this, favorable conditions must be met, in particular the temperature (less than −10 °C) and the optimal amount of water in the cloud. Based on the observed characteristics, this appears to be the most important process of electrification of the thundercloud, which does not eliminate the other electrification processes.

The mechanism by which charge separation occurs is still under investigation and there are more additional hypotheses.

Downloads

Under normal conditions, the Earth's atmosphere is a good electrical insulator. The dielectric strength of air at sea level reaches three million volts per meter, but gradually decreases with altitude, mainly due to the rarefaction of the air. As the charges in the cloud separate, the electric field increases. it becomes more and more intense and eventually exceeds the dielectric strength of air. Thus, a path of conductive plasma emerges through which electrical charges can flow freely, thus forming an electrical discharge called lightning, reaching hundreds of millions of volts.

Lightning occurs in various forms and is often categorized by the "start" and "end" points of the flash channel:

- beams inside a cloud or intranubous (Intra-cloud, or IC), those that occur within a single storm cloud and are the most frequent;

- cloud to cloud or internubous rays (Cloud-to-cloudor CC, or inter-cloud lightning), which begin and end in two different "functional" storm clouds;

- cloud-to-ground rays (Cloud-to-ground, or CG), which originate mainly in the storm cloud and end on the Earth's surface, although they can also occur in the reverse direction, that is, from land to cloud. There are variations of each type, such as cloud-to-ground "positive" flashes against "negative," which have different common physical characteristics that can be measured.

Negative discharge from cloud to ground

The discharge begins when the first break in the dielectric strength of the air occurs, from the region occupied by the negative charges, inside the cloud, traversed by a channel in which the charges circulate freely. The tip of the discharge is directed towards the smallest concentration of positive charges, at the base of the cloud. As a result, a large number of electrons travel down the cloud, while the channel continues to expand downward toward the ground. The tip of the discharge advances in stages, fifty meters every fifty microseconds. The lightning tip usually splits into several branches and emits extremely weak light with each jump of discharge. On average, a charge of five coulombs of negative charges accumulates in the ionized channel uniformly, and the electrical current is on the order of one hundred amperes.

The electrons induce an accumulation of opposite charges in the region just below the cloud. From the moment they begin to head towards the ground, positive charges tend to be attracted and regroup at the ends of terrestrial objects. From these points, the air ionizes, making similar ascending trajectories appear, going to meet the first descending trajectory.

Upon contact with the ground or with a ground object, the electrons begin to move much faster, producing an intense luminosity between the cloud and the point of contact. As the electrons and branches begin to pick up speed and move toward the ground, the entire ionized path lights up. All negative charge, including that of the cloud, dissipates into the ground in a flow that lasts a few microseconds. In that interval, however, the temperature inside the road reaches over thirty thousand degrees Celsius.

Typically, three or four discharges occur on average in the same lightning strike, called post return discharges, separated from each other by an interval of about fifty milliseconds. In the event that the cloud still contained negative charges, a new discharge appears, which moves faster than the initial discharge, since it follows the already opened ionized path, reaching the ground in a few milliseconds. However, the number of electrons deposited in subsequent return discharges is generally less than in the first. While initial discharge current is typically about 30 kiloamperes (kA), subsequent discharges have a current of between 10 and 15kA. On average, thirty coulombs are transferred from the cloud to the ground. It is possible to observe lightning mainly thanks to the various return discharges. In general, the average duration of this entire process is 0.20 seconds.

Positive discharge from cloud to ground

Lightning doesn't always come from negatively charged areas of a cloud. In some cases, electrical discharges occur at the top of large cumulonimbus, whose top form extends horizontally. Although they are relatively rare, positive rays have some particular characteristics. Initially, the precursor channel presents a uniformity, different from that which occurs in a negative discharge. When contact is established, only a single return discharge is produced, the peak current of which exceeds 200 kiloamperes, much higher than negative lightning. This process usually takes a few milliseconds. This type of discharge offers a much higher destructive potential than negative discharges, particularly for industrial buildings, due to the large load it carries.

Intracloud discharge

Most lightning strikes usually occur within clouds. A precursor channel for the discharge appears in the negative core at the bottom of the cloud and continues upwards, where positive charges tend to be concentrated. With a typical duration of 0.2 seconds, these discharges have an almost continuous luminosity, punctuated by pulses eventually attributed to the return discharges that occur between the bags. of load. The total charge transferred in such a discharge is of the same order as that of cloud-to-ground lightning.

The discharge begins with the movement of negative charges forming a precursor channel in the vertical direction, which takes 10 to 20 milliseconds and can reach a few kilometers long. When it reaches the top of the cloud, this channel divides into horizontal branches, from which the transfer of electrons from the base of the cloud occurs. Around the start of the discharge channel, negative charges move in its direction, spreading the branches at the base of the cloud and increasing the duration of the discharge. The lightning ends when the main connection between the lower and upper parts of the cloud is broken.

Ground to cloud download

From elevated structures and mountain tops, precursor discharge channels may appear and follow a vertical direction toward the cloud. Therefore, the negative charges stored in the cloud flow towards the ground or, more rarely, the electrons flow towards the cloud. The precursor channel usually emerges from a single point, from which it branches vertically into the cloud. Its appearance is mainly linked to metallic structures, such as buildings and communication towers, whose height reaches more than one hundred meters and whose ends are capable of strengthening the induced electric field and thus starting a precursor discharge. When the connection is established, return emissions occur similar to negative emissions from clouds to the ground.

Observational Variations

Some types of lightning have been named, by ordinary people or scientifically, the best known being:

- Yunque tracking beam (Anvil crawler lightning), sometimes called Ray spider (Spider lightning), it is created when the leaders spread through wide regions of horizontal load in mature electric storms, usually the stratiform regions of the mesoescala connective systems. These discharges usually start as intranubes discharges that originate within the convective region; the negative leader end then spreads well in the load regions mentioned above in the stratiforme area. If the leader is too long, he can be separated into several bidirectional leaders. When this happens, the positive end of the separate leader can hit the ground as a positive flash cloud to earth or crawl down the bottom of the cloud, creating a spectacular sample of lightnings crawling through the sky. Soil flashes produced in this way tend to transfer large amounts of load, and this can trigger upward lightning and lightning in the upper atmosphere..

- globular beam (Ball lightning), also known as spherical beam, sparkle or light dial is an atmospheric electric phenomenon whose physical nature is still controversial. The term refers to reports of luminous objects, usually spherical, ranging from the size of a pea to several meters in diameter. Sometimes it is associated with electric storms, but unlike the rays, which last only a fraction of a second, globular rays last for many seconds. Globulary rays have been described by eyewitnesses, but rarely recorded by meteorologists. Scientific data on globular rays are scarce due to their low frequency and unpredictability. The presumption of their existence is based on informed public sightings and, therefore, has produced somewhat inconsistent findings. Brett Porter, a ranger, reported taking a photo in Queensland, Australia in 1987.

- Beads beam (Bead lightning), also known as Perky beam, chain beam, perlschnurblitz or eclair en chapelet, to name only some, is the decay stage of a channel in which the luminosity of the channel is divided into segments. Almost all downloads will show an account formation when the channel cools immediately after a return coup, which is sometimes called the "out of accounts" stage of lightning. The bead beam is more properly a stage of the discharge of a normal lightning than a kind of lightning itself. The counting of a ray channel is usually a small-scale feature and therefore it is often only apparent when the observer/camera is near the ray.

- Lightning cloud to air (Cloud-to-air lightning) is a ray in which an end of a bidirectional leader comes out of the cloud, but it does not result in a terrestrial lightning. Sometimes, these flashbacks can be considered as failed ground flashes. Blue jets and giant jets are a form of cloud-to-air or cloud-to-ionosphere lightning where a leader is launched from the top of a storm.

- Dry lightning (Dry lightning), name used in Australia, Canada and the United States for the rays that occur without precipitation on the surface. This type of rays is the most common natural cause of forest fires The clouds of pyrocuulonimbos produce rays for the same reason that they produce the clouds cumulonimbu[chuckles]required]

- Forked lightning (Forked lightning) is a ray of cloud to earth that shows ramifications in its path.

- heat beam (Heat lightning), it is a lightning that seems not to produce a perceptible thunder because it occurs too far for the thunder to be heard. The sound waves are dissipated before reaching the observer.

- tape beam (Ribbon lightning), which occur in storms with strong winds crossed and multiple blows of return. The wind, at each successive blow of return, will move slightly to one side the trajectory regarding the previous return coup, causing a tape effect.

- Lightning rocket (Rocket lightning), is a form of cloud download, usually horizontal and at the base of the clouds, with a luminous channel that seems to advance through the air with a speed that can be solved visually, often intermittently.

- blade beam (Sheet lightning), it is an intern lightning that shows a diffuse brightness of the surface of a cloud, caused because the actual download route is hidden or too far. The lightning itself cannot be seen by the viewer, so it appears only as a flash or a blade of light. Lightning can be too far to discern individual flashes.

- Soft channel beam (Smooth channel lightning) is an informal term that refers to a type of cloud beam to earth that has no visible ramifications and appears as a line with soft curves in opposition to the irregular appearance of most rays channels. They are a form of positive lightning generally observed in, or near, the convective regions of severe electrical storms in the northern center of the United States. It is theorized that severe electrical storms in that region get a "inverted" load structure in which the main positive-charge region is below the main negative-charge region instead of above it, and as a result these storms generate predominantly positive rays from cloud to earth. The term "soft channel lightning" is also sometimes attributed to upward lightnings from land to cloud, which are generally negative flashes initiated by upward positive leaders of high constrctions.

- Lightning staccato (Staccato lightning) is a ray of cloud to earth that is a short-lived blow that (often, but not always) appears as a single very bright flash and often has a considerable ramification. They are often found in the area of the visual vault near the mesocyclone of rotary electric storms and coincide with the intensification of the ascending currents of the electric storms. A similar cloud-to-cloud impact consisting of a brief flash on a small area, which appears as a signal, also occurs in a similar area of swivel up currents.

- superbolts are defined quite vaguely as impacts with an energy source of more than 100 gigajulios [100 GJ] (most rays are about 1 gigajulio [1 GJ]). Events of this magnitude occur with a frequency of one every 240 downloads. They are not categorically different from ordinary rays, and simply represent the upper edge of a continuum. Contrary to the wrong popular idea, superbolts may have a positive or negative charge, and the load ratio is comparable to that of a "ordinary" ray.

- Nice lightning (Sympathetic lightning) is the tendency of lightning to coordinate freely through long distances. Downloads can appear in groups when viewed from space.[chuckles]required]

- ascending beam (Upward lightningor Earth to cloud beam (ground-to-cloud lightning) is a beam that originates at the top of an object connected to the ground and spreads up from that point. This kind of lightning can be caused by a previous lightning, or it can start completely on its own. The first is usually found in regions where spider rays occur and can involve multiple objects connected to land simultaneously. The latter usually occurs during the cold season and may be the type of dominant lightning in storm and snowy events.

- clear skylight (Clear-air lightning) are lightning that occurs without an apparent cloud near enough to have produced them. In the USA Rocky Mountains. U.S. and Canada, an electric storm may be in an adjacent valley and not be observable from the valley where lightning falls, either visually or audibly. Similar events are also experienced in European and Asian mountain areas. Also in areas such as sounds, large lakes or open plains, when the storm cell is above the near horizon (about 25 km) there may be some distant activity, a discharge may occur and as the storm is far away, the blow is known as a fallen lightning from the sky (about 25 km).a bolt from the blue). These flashes usually begin as normal internubous flashlights before the negative leader exits the cloud and hits the ground at a considerable distance. Positive discharges in clear air can occur in highly clumsy environments where the higher positive load region moves horizontally from the precipitation area.

Artificial discharge

Artificial lightning can be obtained by means of small rockets that, as they rise, have a thin metallic thread attached to them. As the device rises, this thread unfurls until, under the right conditions, an electrical discharge occurs by passing through the thread to the ground. The thread is instantly vaporized, but the path that the electric current follows is generally straight thanks to the path of the ionized atoms left by the thread. It is also possible to create beams initiated by laser beams, which create filaments of plasma for short moments, allowing allow electrical charges to flow and cause an electrical discharge.

Particularities

Lightning strikes often appear intense and bright, sometimes producing a strobe effect. The luminosity of lightning can be seen several tens of kilometers away. This phenomenon is called "heat lightning" because it is usually associated with summer thunderstorms. When lightning occurs inside a cloud, the lightning is able to completely illuminate the cloud, also illuminating the sky.

Finally, intracloud discharges can manifest as extremely branched channels that extend horizontally in the highest regions of the cloud, over a large part of it. Rays that are distributed horizontally generally appear to move slower than average. In cloud-to-ground discharges, ribbon-like lightning is possible. This is due to strong winds that can move the ionized channel. In each discharge, the lightning appears to move laterally, forming segments parallel to each other. Positive discharges, because they originate at the top of the cumulus, can extend beyond the region of the storm, into an area where the weather is stable, miles away. The channel of this type of lightning can travel horizontally for a few kilometers before suddenly heading towards the ground.

Discharges of all kinds leave a channel of extremely hot ionized air through which they pass. By cutting off the flow of electrical charges, the remaining channel quickly cools and breaks down into several smaller parts, creating a sequence of rapidly disappearing luminous dots. The segments are formed because the channel does not have a constant thickness throughout its length and the thickest parts take longer to cool. This phenomenon is extremely difficult to observe, because the entire process takes only a small fraction of a second. A phenomenon called ball lightning has also been reported. It has an average diameter of between eight and fifty centimeters, appears to appear in thunderstorms, is less bright than other lightning bolts, and generally moves horizontally in a random direction. This phenomenon lasts only a few seconds. There are many doubts about its existence, which has not yet been proven, although there are many historical testimonies, some report having seen it inside buildings.

Other sources

In addition to storms, volcanic activity produces favorable conditions for lightning strikes in multiple forms. The enormous amount of pulverized material and gases explosively expelled into the atmosphere creates a dense column of particles. The density of ash and the constant movement within the volcanic column produce charges by frictional interactions (triboelectrification), which cause very powerful and very frequent flashes when the cloud tries to neutralize itself. The amplitude of electrical activity is directly dependent on the size of the ash cloud; and this depends in turn on the intensity of the eruption. Due to the high content of solid material (ash), and in contrast to the water-rich source areas of a normal thundercloud, it is often referred to as a dirty storm or a volcanic storm, and is generally cloud-confined and few of them reach more remote areas. However, they are a major source of interference to radio transmissions and sometimes cause forest fires. There is also lightning from smoke clouds from large fires.

- powerful and frequent flashes have been seen in the volcanic column since the Vesuvius eruption in 79 AD. related by Plinio el Joven.

- Also, the vapors and ashes that originate in the vents of the volcano's flanks can produce smaller and localized flashes more than 2.9 km long.

- Small and short-lived sparks, recently documented near the newly extruded magma, testify that the material is very loaded before even entering the atmosphere.

Thermonuclear explosions can cause electrical shocks. These phenomena usually occur through the transfer of electrons from the ground to the atmosphere, forming ionized channels several kilometers long. The origin of the phenomenon is unknown, but it is possible that the radioactive release from the explosion played a role.

Sandstorms are also sources of electrical discharges that can come from the collision between sand particles that, upon contact, accumulate charges and generate discharges. Intense bushfires, such as those seen in the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season, can create their own weather systems that can produce lightning strikes and other weather phenomena. The intense heat from a fire causes the air to rise rapidly inside of the column of smoke, causing the formation, in an unstable atmosphere, of pyrocumulonimbus clouds. This turbulent, rising air draws in cooler air, which helps cool the spine. The rising plume is further cooled by the lower atmospheric pressure at high altitude, allowing moisture to condense into clouds. These weather systems can produce dry lightning, fiery tornadoes, high winds, and dirty hail.

Related phenomena

Lightning produces electromagnetic radiation of different frequencies, especially visible light, radio waves, and high-energy radiation. These radiations characterize lightning. The increase in temperature in the lightning channel, on the other hand, produces sound waves that form thunder. Variation of the discharge electric field is also the cause of other types of transient phenomena in the upper atmosphere. In general, lightning occurs in greater quantity during storms. When a discharge falls directly on a sandy ground, the immense temperature causes the fusion of its particles that, once the current is cut, melt and form a fulgurite, whose shape acquired corresponds to the path of the discharge on the ground.

Thunder

Sound waves caused by an electrical discharge characterize thunder. They are due to the rapid expansion of the air due to the overheating of the discharge channel. The frequency varies between a few hertz and a few kilohertz. The time interval between the sight of lightning and the perception of thunder is differentiated by the fact that light travels much faster than sound, which has a speed of 340 m /s.

When lightning strikes within 100 meters of a listener, thunder presents as a sudden high-intensity sound wave lasting less than two seconds, followed by a loud boom that lasts several seconds until it dissipates. The duration of the thunder depends on the shape of the beam, and the sound waves propagate in all directions from the whole of the channel, resulting in a large difference between the part closest to the listener and the part furthest away from the listener. As sound waves are attenuated by the atmosphere, the thunder associated with lightning strikes over great distances becomes inaudible after traveling a few miles and therefore loses energy. In addition, the fact that storms occur in areas of atmospheric instability favors the dissipation of sound energy.

High-energy radiation

Lightning produces radiation in a wide variety of ranges in the electromagnetic spectrum, ranging from ultra-low frequencies to X-rays and gamma rays, including the visible spectrum. X-rays and gamma rays are of high energy and result from the acceleration of electrons in a strong electric field at the moment of discharge. They are attenuated by the atmosphere, with X-rays being limited to the vicinity of the beam, while gamma rays, although their intensity decreases considerably with distance, can be detected both from the ground and from artificial satellites. Thunderstorms are generally associated with gamma-ray flashes appearing in Earth's upper atmosphere. Some satellites, such as AGILE, monitor the appearance of this phenomenon, which occurs dozens of times throughout the year.

Models suggest that an exotic type of discharge can occur inside storms, in which the interaction between high-energy electrons and their corresponding antimatter, positrons, occurs. This process leads to the production of more energized particles that ultimately cause gamma-ray bursts. These discharges are extremely fast, faster than lightning itself, and despite the large amount of energy involved, they emit little light. Aircraft crossing near storms may receive large doses of radiation, although conclusive results have not yet been obtained.

Colours and Wavelengths

Along the way, the discharge superheats gases in the atmosphere and ionizes them (the temperature can be as much as five times that of the surface of the sun, or 30,000K). A conductive plasma is formed, causing the sudden emission of observable light. The color of that ray depends on several factors: the current density, the distance from the observer to the ray, and the presence of different particles in the atmosphere. In general, the perceived color of lightning is white in dry air, yellow in the presence of a large amount of dust, red in the presence of rain, and blue in the presence of hail.

The perception of the white color of lightning is also linked to the set of wavelengths of the different elements present in electrified air. The presence in the atmosphere of oxygen and nitrogen contribute to wavelengths corresponding to green (508 to 525 nm); to yellow-orange (599 nm) for oxygen; and blue (420 to 463 nm) and red (685 nm) for nitrogen.

Radio parasites

Electrical discharge is not limited to visible wavelengths. It is reflected in a broad domain of electromagnetic radiation that includes radio waves. As these emissions are random, they are referred to as "atmospheric parasites". The waves created propagate white noise that is superimposed on telecommunication signals, resembling to a creak to a listener. These parasites range from low frequencies to the UHF bands.

Schumann Resonances

Between the Earth's surface and the ionosphere, at an altitude of a few tens of kilometers, a cavity is formed inside which electromagnetic radiation of extremely low frequency or ELF (on the order of a few hertz) are trapped. As a result, the rays circle the Earth several times until they dissipate. In this range of frequencies, lightning produces radiation, which is why they are the main sources for the maintenance of this phenomenon called “Schumann resonances”. The superposition of the radiations emitted at any time and the resulting resonances produce radiation peaks that can be measured. Schumann resonance monitoring is an important method for monitoring storm-related electrical activity on the planet and can therefore be used in global climate analysis.

Transient light phenomena

In the Earth's high atmosphere, above the storm clouds, some particular emissions are produced, with different characteristics, which are collectively called transient light phenomena. Although they extend for tens of kilometers in the stratosphere and mesosphere, it is practically impossible to observe them with the naked eye, mainly due to their low luminosity. However, cameras installed on planes, satellites or even on the ground, but aimed at storms near the horizon, are capable of proving the existence of these phenomena. Its origin is attributed to the excitation of electricity by the variation of the electric field, in particular during the occurrence of cloud-to-ground lightning.

Among the most notable transients are spectra, which appear immediately above large lightning bolts during a thunderstorm, usually displaying reddish colors and cylindrical shapes resembling tentacles. The blue jets, in turn, appear at the top of the large storm clouds and propagate in a vertical direction up to about fifty kilometers in height. Both have a maximum duration of a few milliseconds. Finally, elves (for ELVES, an acronym for Emission of Light and Very low-frequency perturbations from Electromagnetic pulse Sources) are disk-shaped and last a few milliseconds. Its origin may be due to the propagation of an electromagnetic pulse generated at the time of the discharges in the cloud below.

Distribution

Frequency of lightning strikes

Thanks to satellite observations, it is possible to estimate the distribution of lightning throughout the world and verify that it is not evenly distributed. The frequency of lightning is about 44 (±5) times per second, or nearly 1.4 billion flashes per year, with the average duration of 0.2 seconds being made up of a much shorter number of flashes (strikes) of about 60. to 70 microseconds. Many factors affect the frequency, distribution, power, and physical properties of a typical lightning strike in a particular region: terrain altitude, latitude, prevailing wind currents, relative humidity, and proximity to bodies of light. hot and cold water. This occurs both from the mixing of warmer and colder air masses, and from differences in moisture concentrations, and generally occurs at the boundaries between them. The flow of warm ocean currents across drier land masses, such as the Gulf Stream, partly explains the high frequency of lightning strikes in the southeastern United States. Because large bodies of water lack the topographic variation that would give rise to atmospheric mixing, lightning strikes are noticeably less frequent in the world's oceans than on land. The north and south poles have limited coverage from thunderstorms and therefore happen to be the areas with the fewest lightning strikes.

Because humans are terrestrial and most of their possessions are on Earth, where lightning can damage or destroy them, cloud-to-ground lightning is the most studied and best understood of the three types, although intracloud and intercloud lightning are the most common types of lightning (cloud-to-ground lightning accounts for only 25% of all lightning strikes in the world; to some extent, the proportion also varies seasonally in the mid-latitudes). The relative unpredictability of lightning limits a full explanation of how or why it occurs, even after hundreds of years of scientific investigation. Approximately 70% of lightning strikes occur over land in the tropics where atmospheric convection is greatest. Of these rays, more than 90% are distributed over the emerged lands. Instrument data shows that most lightning strikes occur in tropical and subtropical regions, primarily in central Africa, southern and southeastern Asia, central South America, and the United States. The Congo Basin experiences a large number of lightning strikes in several places, especially in Rwanda, where the density of lightning strikes exceeds 80 cases per square kilometer per year, the highest in the world. The particular place where lightning occurs most frequently is near the small village of Kifuka in the eastern mountains of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the elevation is around 975 m. On average, this region receives 158 downloads/km²/year.. Lake Maracaibo, in Venezuela, has an average of 297 days a year with activity of lightning strikes, an effect recognized as Catatumbo lightning. Other hot spots with lightning strikes are Singapore and Lightning Alley in central Florida. High buildings tend to receive more discharges. For example, the Empire State Building in New York is struck twenty times a year, of which more than half are ground-cloud discharges. The Christ the Redeemer statue in the city of Rio de Janeiro receives an average of six lightning strikes throughout the year. In the North and South polar regions, by contrast, lightning is virtually non-existent. Because the concentrated charge within the cloud must exceed the insulating properties of air, and this increases proportionally with the distance between the cloud and the ground, the ratio of cloud-to-ground impacts (versus intracloud and intercloud) increases when the cloud it is closer to the ground. In the tropics, where the freezing level is generally higher in the atmosphere, only 10% of lightning is CG. At the latitude of Norway (around 60°N), where the freezing altitude is lower, 50% of the lightning strikes are cloud-to-ground. Lightning is generally produced by cumulonimbus clouds, which have their beams typically 1 -2 km from the ground and reaching a height of up to 15 km.

The occurrence of lightning is directly related to convective systems that, at the height of their activity, can produce more than one lightning strike per second. Storms with mesoscale convective complexes, such as tropical cyclones and hurricanes, reach extreme levels of lightning, peaking at more than one cloud-to-ground lightning strike per second. The formation of supercell storms also has a strong relationship with the appearance of positive lightning, with more than thirty occurrences per hour. The relationship between the discharge rate in a supercell thunderstorm and the formation of tornadoes is still unclear. It is also of note that cloud-to-ground lightning can occur exactly below where the cloud shows its maximum altitude, although that relationship has not yet been confirmed for all types of storms, especially those that occur over the ocean. Although lightning is always associated with thunderstorms, and thunderstorms produce rain, the direct relationship between the two phenomena is unknown. In tropical regions, electrical activity is mainly concentrated during the summer months.

Global warming may be causing an increase in lightning strikes around the world. However, the predictions differ between a 5 and 40% increase in the current incidence for each degree Celsius of average increase in atmospheric temperature.

A mathematical model developed by Marcia Baker, Hugh Christian and John Latham allows to estimate the frequency of rays, represented by the letter f{displaystyle f}. According to the model, this is proportional to radar reflectivity Z{displaystyle Z} and the amplitude of the upward movement R{displaystyle R} and also depends on the concentration of ice crystals and ice grains in the cloud. In some cases, the frequency of rays is also proportional to the power of a high number of the speed of the upward movements of the air w{displaystyle w}. The power considered is generally six, i.e. w6{displaystyle w^{6}According to another model, valid for tropical storms, the frequency of rays is proportional to the power of five of the depth of the cold front. The depth of the cold front, which represents the difference between the altitude of the summit of the tropical storm and the point where it is at 0 °C, is in turn proportional to the charge rate and static electricity stored in the convective clouds.

Records

On June 25, 2020, the World Meteorological Organization announced the recording of two lightning records: the longest in distance traveled and the longest in duration, called "megalightnings." The first, in the southern Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, traveled 709 km in a horizontal line, cutting through the northern state on October 31, 2018, more than double the previous record, registered in the state of Oklahoma, in the United States, with 321 km (duration of 5.7s). The longest-duration lightning strike, 16.73 seconds, occurred in Argentina, from a discharge that began in the north of the country on March 4, 2019, which was also more than double the previous record of 7.74 seconds, recorded in Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, France, on 30 August 2012.

Roy Sullivan, a ranger at Shenandoah National Park, holds the record for the number of lightning strikes on a man. Between 1942 and 1977, Sullivan was struck by lightning seven times and survived each time.

Detection and monitoring

The oldest ray analysis technique, used since 1870, is spectroscopy, which consists of breaking down light at different frequencies. This method made it possible to determine the temperature inside a lightning bolt, as well as the density of the electrons in the ionized channel., in addition to its location, its intensity and its shape. Devices capable of directly measuring the incident electric current are generally installed in environments where the incidence of lightning is high, particularly in tall buildings and on mountain tops. The use of cameras allowed the systematic analysis of the stages of an electric discharge. Since lightning has a very short duration, high-speed cameras are essential to detect the time intervals in which charges break the dielectric strength of the air and transfer electrical charges between two regions, especially after comparing the images with the variation. of the electromagnetic field. On tall structures, such as buildings and communication towers, sensors are installed to allow a direct assessment of the amount of loads passing through them during a storm. To monitor emissions over a large area, strategically installed sensor networks have been created to accurately detect the location of the electromagnetic waves emanating from the discharges. However, only with the launch of satellites capable of counting all the discharges on a global scale, it was possible to obtain the true dimension of the electrical activity of the planet.

Devices shipped into clouds provide important data about the load distribution of a cloud. Weather balloons, small rockets and properly equipped aircraft are deployed deliberately in thunderstorms and are hit dozens of times by discharges.

There are also detection systems on the ground. The field mill is an instrument for measuring the static electric field. In meteorology, this instrument allows, thanks to the analysis of the electrostatic field above it, to indicate the presence of an electrically charged cloud that indicates the imminence of lightning. There are also networks of receiving antennas that receive a radio signal generated by the download. Each of these antennas measures the intensity of the lightning and its direction. By triangulating the directions taken from all the antennas, it is possible to deduce the position of the discharge.

Mobile systems with a directional antenna can infer the direction and intensity of the lightning strike, as well as its distance, by analyzing the frequency and amplitude attenuation of the signal. Artificial satellites in geostationary orbit can also measure the lightning produced by electrical storms that sweeps the viewing area looking for flashes of light. Among others, the GOES and Meteosat series of satellites are located approximately 36,000 km from Earth. At that distance, the thickness of the atmosphere can be neglected and the position in latitude and longitude can be deduced directly.

Lightning detector networks are used by meteorological services such as the Canadian Weather Service, Météo-France and the US National Weather Service to monitor storms and warn populations. Other private users and Governments also use them, including in particular forest fire prevention services, electricity transmission services, such as Hydro-Québec, and explosives factories.

Dangers and protections

Lightning often strikes the ground, so unprotected infrastructure is prone to lightning damage. The magnitude of the damage caused depends to a large extent on the characteristics of the place where the lightning strikes, in particular its electrical conductivity, but also on the intensity of the electrical current and the duration of the discharge. The sound waves generated by lightning usually cause relatively minor damage, such as breaking glass. When an object is struck, the electrical current increases its temperature enormously, making combustible materials a fire hazard.

For men

There is no reliable data on the number of lightning-related fatalities worldwide, as many countries do not account for such accidents. However, the risk zone is between the tropics, where approximately four billion people live. In Brazil, 81 people died from electric shocks in 2011, including a quarter in the north of the country. According to INPE researchers, the number of deaths is directly related to the lack of education of the population regarding lightning strikes. In the South East region, for example, the number of fatalities has decreased, even with the increase in the incidence of lightning strikes. In the country, most of those affected are in the countryside, are engaged in agricultural activities and use metal objects such as hoes and machetes. The second main cause is the proximity of metallic vehicles and the use of motorcycles or bicycles during a storm.

In the event of a storm, the best form of personal protection is to seek shelter. Enclosed houses and buildings, especially those equipped with electrical shock protection systems, are the safest. Metal vehicles, such as cars and buses, provide reasonable protection, but their windows should be closed and contact with metal items should be avoided. It is recommended to avoid standing near isolated trees, metal towers, metal posts and fences to reduce the chances of being struck by lightning. It is strongly recommended, in risky situations, not to stay in fields, pools, lakes and in the ocean. Inside buildings, it is advisable to avoid the use of any equipment whose conductive surface extends to the exterior areas, such as electrical equipment and water pipes.

Lightning can injure people in several ways: by direct discharge through the body, by the current caused by a nearby discharge, or by contact with a conductive object struck by lightning. Mild symptoms of lightning strike include mental confusion, temporary deafness and blindness, and muscle aches. In such cases, full recovery is usual. In cases of moderate damage, victims may suffer mental disorders, motor impairments, or first and second degree burns. Recovery is possible, but sequelae such as mental confusion, psychomotor difficulties, and chronic pain are likely to persist. Finally, the serious damage caused by electric shocks causes, among other things, cardiac arrest, brain damage, severe burns and permanent deafness. The patient presents, most of the time, irreversible sequelae that mainly affect the nervous system. On average, one in five people struck by lightning dies as a result. Reddish Lichtenberg figures may also appear on the skin of lightning victims, with fern-like patterns that can persist for hours or days. They are sometimes called lightning flowers, and are thought to be caused by the rupture of capillaries under the skin by the passage of high electrical current.

For aviation

The risks in aviation are minor, but not non-existent. Aircraft react to lightning in the same way as a Faraday cage (current flows only through the fuselage) and when an aircraft is struck by lightning it usually enters a sharp point on the aircraft, such as the nose, and exits through the tail. It may happen that the cockpit of the aircraft burns or melts at the points of impact of lightning, but this damage does not present a risk to the passengers of the aircraft and it may even happen that the shock does not occur. sit. Gliders, being smaller than traditional aircraft, can be destroyed mid-flight by lightning.

The parts most at risk are the aircraft's onboard electronics and fuel tanks. The protection of the latter became evident after Pan Am Flight 214, which crashed in 1963 after a lightning strike will create a spark in the fuel tank. The tanks and electronics are secured by grounding secured by heatsinks at the wingtip. Lightning can also confuse airplane pilots. In fact, during Loganair Flight 6780, after the aircraft was struck by lightning, the pilots ignored the previously activated control modes, thinking that the discharge had damaged the electronics. In fact, the aircraft suffered no damage and the pilots spent the rest of the flight compensating for the effects of the still functional autopilot.

For electrical networks

High-voltage lines of the electrical grid are vulnerable elements and there have been many cases of blackouts, the most notable being the New York blackout of 1977 and the power blackout of Brazil and Paraguay of 2009. A discharge over a line transmits high voltage spikes over long distances, causing significant damage to electrical devices and creating risks for users. However, most equipment damage comes from the effects of electromagnetic induction, in which the discharge, passing through an electrical conductor near a transmission cable, induces spike currents and voltages. The electrostatic induction of the flow of charges upon contact with lightning causes sparks and voltage spikes that can be dangerous depending on the circumstances. Underground cables are also prone to unwanted currents. The purpose of the protection equipment is to redirect these currents to earth. The surge arrester is one of the most used equipment. It consists of a metal rod connected to the ground that conducts the lightning safely to it.

Lightning Energy Recovery

The use of lightning energy has been attempted since the late 1980s. In a single flash, an electrical energy of approximately 280 kWh. This corresponds to approximately 1 GJ, or the energy of approximately 31 liters of gasoline. However, less than a tenth of this energy reaches the ground, and this is sporadically in terms of space and time. It has been proposed to use the energy of lightning to produce hydrogen from water, rather than using rapidly heated water. struck by lightning to produce electricity or to capture a safe fraction of the energy by nearby inductors.

In the summer of 2007, a renewable energy company, Alternate Energy Holdings, tested a method of harnessing lightning power. They bought the system design from Steve LeRoy, an inventor from Illinois, who claimed that a small artificial lightning bolt could light a 60 watt light bulb for 20 minutes. The method involves a tower to capture the large amount of energy and a very large capacitor to store it. According to Donald Gillispie, CEO of Alternate Energy Holdings, “We haven't been able to make it work, […] however, given enough time and money, we could probably expand the model […]. It's not black magic, it's just math and science, and it could become a reality."

According to Martin A. Uman, co-director of the University of Florida Lightning Research Laboratory and a leading lightning scientist, little energy reaches the ground and dozens of "lightning towers" would be needed, comparable to those of Alternate Energy Holdings to power five 100-watt light bulbs for one year. Asked by The New York Times about it, he said that the amount of energy in a thunderstorm was comparable to that of an atomic bomb explosion, but at the same time the attempt to capture the energy of the face of the earth was "hopeless". In addition to the difficulty of storing so much energy quickly, another major challenge was predicting when and where storms would occur; even during a storm it is very difficult to predict where exactly lightning will strike.

In culture

Etymology and usage

The word "lightning" comes from Vulgar Latin Latin: fulgura, Latin: Classical Latin fulmen, meaning 'lightning';.

The expression "lightning never strikes [in the same place] twice" is akin to "a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity," meaning something generally considered unlikely. Lightning occurs more and more frequently in specific areas. Since various factors alter the probability of strikes occurring in a given location, repeated lightning strikes have a very low (but not impossible) probability. Similarly, "lightning from nowhere" refers to something totally unexpected, and "a person struck by lightning" is an imaginative or comedic metaphor for someone experiencing a sudden, shocking, once-in-a-lifetime revelation, similar to an epiphany or enlightenment.

In French and Italian, the expression used to express "love at first sight" is coup de foudre and colpo di fulmine, respectively, which literally translated mean & #39;lightning strike. Some European languages have a separate word for lightning that strikes the ground (as opposed to lightning in general); it is often a cognate of the English word 'rays'. Lightning is often synonymous with speed, hence the expression "at the speed of lightning." Many movie or comic book characters bear lightning-related names or logos to indicate their speed, such as Flash McQueen ("Lightning McQueen", in English) or various superheroes from Marvel Comics and DC Comics publishers.

Mythology

Ancient peoples created many mythological stories to explain the appearance of lightning. In Ancient Egyptian religion, the god Typhon casts lightning bolts on the earth. In Mesopotamia, a document dating from 2300 B.C. C. shows a goddess on the back of a winged creature holding a handful of rays in each hand. She is also in front of the god who controls the weather; he creates thunder with a whip. Lightning is also the mark of the goddess of Chinese mythology Tien Mu, who is one of the five dignitaries of the "Ministry of Storms", commanded by Tsu Law, the god of thunder. In India, the Vedas describe how Indra, the son of Paradise and Earth, carried thunder on his biga. He is considered the god of rain and lightning and the king of the Devas. The Shinto god Raijin, god of lightning and thunder, is depicted as a demon who beats a drum to create lightning.

About 700 B.C. C., the Greeks began to use the symbols of lightning inspired by the Middle East in their artistic manifestations, attributing them mainly to Zeus, the supreme god of their mythology. An ancient story tells that when Zeus was at war against Cronos and the Titans, he freed his brothers Hades and Poseidon along with the Cyclops. In turn, the Cyclops gave Zeus the lightning bolt as a weapon and it became their symbol. In ancient Greece, when lightning appeared in the sky, it was seen as a sign of disapproval from Zeus. The same interpretation was made in ancient Rome with respect to Jupiter. In Rome, it was believed that laurel branches were "immunized" against the action of lightning, so the emperor Tiberius used these branches to protect himself during storms.

In Old Norse religion, lightning was believed to be produced by the magical hammer Mjöllnir belonging to the god Thor. Perun, god of thunder and lightning, is the supreme god of the Slavic pantheon, and Pērkons/Perkūnas, god of Baltic thunder, is one of the most important deities in his pantheon. In Finnish mythology, Ukko (the Old Man) is the god of thunder, the sky and the weather and the Finnish word for thunder is ukkonen.).

In the Inca religion, Illapa is the god of lightning, thunder, lightning, rain and war. Despite the fact that the main faculty of his deity was lightning and its other elements, Illapa had absolute control of the weather. Due to his aforementioned powers, Illapa was considered the third most important god within the Inca pantheon. He was only surpassed by Wiracocha and Inti. Illapa is represented as an imposing man dressed in brilliant gold and precious stones who lived in the upper world. Illapa carried a warak'a and a golden maqana with which he produces the rays. Another representation that was given to Illapa was that of a warrior formed by stars in the celestial world. Illapa manifested itself in the earthly world in the form of a puma or hawk.

In many other cultures, lightning has also been seen as part of a deity or a deity itself, such as the Aztec god Tlaloc or the god K in Mayan religion.

The Buryats, a people who lived near Lake Baikal in southern Siberia, believed that their god produced lightning by throwing stones from the sky. Some indigenous tribes in North America and Africa hold the belief that lightning is produced by a magical "thunder bird", which throws clouds towards the Earth. In the traditional religion of African Bantu tribes such as the Baganda and Banyoro from Uganda, lightning is a sign of the wrath of the gods. The Baganda specifically attribute the lightning phenomenon to the god Kiwanuka, one of the gods among the Lubaale, part of the main trio of gods of the sea or lakes. Kiwanuka starts forest fires, pummeling trees and other tall buildings, and a series of shrines are established in the hills, mountains, and plains to stay in his favor. Lightning is also known to be invoked upon one's enemies by uttering certain chants, prayers, and making sacrifices.

In Judaism, when seeing lightning, one must recite the blessing "...he who does acts of creation." The Talmud refers to the Hebrew word for heaven (Shamaim) as being built of fire and water (Esh Umaim), since the sky is the source of unexplained mixture of "fire" and water that come together, during rain storms. This is mentioned in several sentences, Psalm 29, and discussed in Kabbalah writings.

In Islam, the Qur'an says: “He it is Who shows you lightning, fear and hope, and lifts up the clouds. The thunder sings the praise of him and (also) the angels for fear of Him. He throws the thunder and strikes whoever He wants ». (Quran 13.12-13) and "Have you not seen how God makes the clouds move gently, then joins them together, then makes them into a pile, and then you see the rain coming out..." (Quran 24.43). The previous verse, after mentioning clouds and rain, speaks of hail and lightning: «...and He sends hail from the mountains (clouds) in heaven, and He strikes with it whomever He wills, and drives them away. who wants."

In Christianity, the second coming of Jesus is compared to lightning. (Matthew 24:27, Luke 17:24)

Ceraunoscopy is divination by observing lightning or hearing thunder. It is a type of aeromancy.

In the arts

The lightning bolt was a commonly used motif in Art Deco design, especially the zig-zag design of the late 1920s.

Some photographers, known as storm chasers, have specialized in lightning clichés. A museum entirely dedicated to lightning operated between 1996 and 2012 in the heart of the Volcanoes d'Auvergne regional nature park]. The Lightning Field is a work by the artist Walter De Maria created in 1977, a piece of land art found in New Mexico, United States, and consists of several steel poles for that can be struck by lightning.

Other representations

Lightning bolts are also used in the logos of various brands and associations. Thus, Opel and the European squatter movement.

Some political parties use lightning as a symbol of power, such as the People's Action Party of Singapore, the British Union of Fascists during the 1930s, and the United States' Rights Party in the United States during the 1950s. The Schutzstaffel (SS), the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, used the Sig rune in their logo symbolizing lightning. The German word Blitzkrieg, which means 'lightning war', was an important offensive strategy of the Third Reich during World War II, which consisted of using a powerful armed force to accelerate fighting.. Hard rock band AC/DC also use lightning in their logo. The name of Australia's most famous thoroughbred horse, Phar Lap, derives from the common Zhuang and Thai word for lightning.

The lightning bolt in heraldry is shown as a zigzag with blunt ends. This symbol generally represents power and speed.

Lightning is used to represent the instantaneous communication capabilities of electric telegraphs and radios. The lightning bolt is a common insignia for military communications units around the world. A lightning bolt is also the NATO symbol for a signal asset.

The symbol for electrical hazards is usually lightning. This is recognized by several standards. The Unicode symbol for lightning is "☇" (U+2607).

Alien Rays

Atmospheric electrical discharges are not exclusive to Earth. On several other planets of the Solar System, the existence of lightning of variable intensity has already been confirmed. From these observations it can be deduced that the probability of occurrence of electrical discharges is directly associated with the presence of water in the atmosphere, although it is not the only cause.

On Venus, discharges were suspected due to its thick atmosphere, which was confirmed by the Venus Express probe shipment. Direct signs of electrical discharges have already been detected on Mars. They are possibly caused by the great sand storms that occur on the planet. According to the researchers, Martian electrical activity has important implications because it modifies the composition of the atmosphere, which affects habitability and the preparations for human exploration.

At Jupiter, several missions have made it possible to observe electrical discharges in the equatorial and polar regions. Storms are caused there by convection, just like on Earth. Gases, including water vapor, rise from the depths of the planet, and small particles, when they freeze, rub against each other, thus generating an electrostatic charge that is discharged in the form of lightning. Since Jupiter's storms are much larger and more intense than those on Earth, lightning is much more powerful. The intensity is up to ten times greater than any lightning strike already recorded on our planet. On Saturn, lightning is much less common. However, the appearance of large storm systems causes the appearance of discharges that exceed ten thousand times the energy of terrestrial lightning. On the contrary, on Titan, one of its natural satellites, no electrical discharge has been recorded to date despite a thick and active atmosphere.

Contenido relacionado

Richard L.M. Synge

Sorting algorithm

Large-scale structure of the universe