Rationalism (architecture)

Rationalism, also called the International Style or Modern Movement, was an architectural style that developed around the world between 1925 and 1965, approximately. It is usually considered the main architectural trend of the first half of the XX century. It was a movement of wide international scope, which developed throughout Europe, the United States and many countries in the rest of the world. Among his outstanding figures are: Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Jacobus Johannes Pieter Oud, Richard Neutra, Rudolf Schindler, Philip Johnson, Alvar Aalto, Eliel and Eero Saarinen, Erik Gunnar Asplund, Josep Lluís Sert, Louis Kahn, Pier Luigi Nervi, Gio Ponti, Kenzō Tange, Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer.

This movement does not have a homogeneous designation in all countries. In Spanish, the term "rationalism" is more often used, although in other countries —especially in the Anglo-Saxon world— this term is usually limited to the Italian sphere, to the rationalism practiced by the Gruppo 7 and the M.I.A.R. In contrast, in these other countries the term "International Style" (in English: International style) is more frequently used, which originates from the exhibition organized by Henry- Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1932 and in the book published by both The International Style: Architecture since 1922. A synonymous term is "Modern Movement" (in English: Modern Movement), from the book Pioneers of Modern Movement from William Morris to Walter Gropius (1936), by Nikolaus Pevsner. The latter has a broader meaning and would include, in addition to rationalism or International Style, the avant-garde movements of the first two decades of the XX century. , such as expressionism, cubism, futurism, neoplasticism and constructivism, sometimes considered generically as "pre-rationalism" or "pro-rationalism".

This current sought an architecture based on reason, with simple and functional lines, based on simple geometric shapes and materials of an industrial order (steel, concrete, glass), while renouncing excessive ornamentation and giving great importance to the design, which was equally simple and functional. Rationalist architecture had a close relationship with technological advances and industrial production, especially due to the staunch defense of said relationship advocated by Walter Gropius since the founding of the Bauhaus in 1919. He also advocated the use of prefabricated elements and removable modules. Its formal language was based on a geometry of simple lines, such as the cube, the cone, the cylinder and the sphere, and it defended the use of a free plan and façade and the projection of the building from the inside out. One of its main premises was functionalism, a theory that postulated the subordination of architectural language to its function, without considering its aesthetic aspect or any other secondary premise.

As indicated by its name «Modern Movement», it was a style committed to the values of modernity, in parallel to the so-called «artistic avant-garde» that was developing at that time in plastic arts. It was a movement concerned with the improvement of society, with influencing the improvement of people's lives, through an innovative language that meant a break with tradition in search of a new way of building, of a new way of interpreting the relationship of the human being with his environment and to look for new solutions that would solve the problem of the increase of the population in the big cities. To do this, he used not only theoretical contributions, new ways of conceiving spaces and using design as a tool to combine functionality and aesthetics, but also technical and industrial advances, the use of new techniques and new materials..

In addition to architecture, this movement was interested in urban planning and design. He also promoted architectural theory and the organization of congresses and conferences for the dissemination of the new movement, which materialized in the constitution in 1928 of the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM), as well as its executive body, the International Committee for the Resolution of Contemporary Architecture Problems (CIRPAC).

Terminology

First of all, it is convenient to analyze the terminology applied to this movement. Except for small nuances, in general it can be considered that rationalism, the International Style and the Modern Movement are synonymous concepts. As its etymology indicates, rationalism comes from reason and has its origin in the claim of the new architecture to rationalize the construction processes. Rationalism was heir to the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, the culmination of a long process of application in architecture of the new mechanization processes initiated with the industrial era. This process evolved in parallel to social advances, with a certain utopian component of applying the values of architecture and urbanism to the improvement of society: industrialization, used in a "rational" way, would serve, according to the theorists of the movement, to solve social injustices and create an urban environment that optimally encompasses the majority of the population. Some historians point to the origin of the term in this phrase by Erwin Piscator:

The new architecture should no longer influence the spectator by merely sentimental means, should not speculate more about its emotive availability, but should turn, in a totally conscious way, to its reason.Erwin Piscator, Das politische TheaterBerlin, 1929.

The term «International Style» (in English: International style) comes from the exhibition Modern Architecture - International Exhibition organized by Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 1932 and in the book published by both The International Style: Architecture since 1922. Despite its ambiguity, the term made a fortune and is the most widely used in the Anglo-Saxon sphere to designate the most orthodox phase of rationalism. For Hitchcock and Johnson, the International Style encompassed the most symptomatic productions of both rationalism and neoplasticism, characterized by a rational language based on industrial production. Sometimes the term rationalism is circumscribed to Europe, while the International style would describe it globally. Another term used in this context is "internationalism", from the book Internationale Architektur by Walter Gropius (1925).

The term «Modern Movement» (in English: Modern Movement) comes from the book Pioneers of Modern Movement from William Morris to Walter Gropius (1936), by Nikolaus Pevsner, and would be more inclusive, since it would bring together rationalism with expressionism, cubism, futurism, neoplasticism and constructivism, considered generically as a "pre-rationalism" (or "pro-rationalism"). The author's intention was to point out the convergence of various stylistic currents towards a new way of conceiving architecture during the first decades of the XX century. According to Pevsner, “it is essential to understand the Modern Movement as a synthesis of the Morris movement (Arts & Crafts), the development of steel construction and art nouveau”. It is interesting to note that as early as 1902 the architect Otto Wagner had used the same term in the preface to his book Moderne Architektur. However, in recent times some historians have criticized some of Pevsner's formulations, especially regarding the alleged loss of historical roots in modern architects, noting for example that Le Corbusier was largely inspired by classical Greco-Roman architecture and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe by the work of neoclassical architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Another of the premises put in doubt has been that of a common supranational style, against which a wide divergence of national-based criteria has been pointed out in each of the countries where the movement developed, although on numerous occasions they converged on criteria common. Thus, in contrast to the initial postulates of Pevsner and Siegfried Giedion, from the 1970s various historians criticized the concept of the Modern Movement, such as Reyner Banham, Bruno Zevi or Manfredo Tafuri, while Charles Jencks went on to speak of "modern movements". in the plural.

It should be noted that in some countries, especially in the Anglo-Saxon sphere, the term «modernism» is used as a synonym for the Modern Movement. However, in Spanish that term is used for the artistic style developed between the end of the XIX century and the beginning of the xx also known as art nouveau in France, Modern Style in the UK, Jugendstil > in Germany, Sezession in Austria, Nieuwe Kunst in the Netherlands or Liberty in Italy.

Finally, it should be noted that the Modern Movement is not the same concept as modern architecture, which is the architecture of modernity, a cultural process that began with the Enlightenment in the XVIII based on science and progress, linked to philosophical positivism. It therefore includes the centuries xix, xx and xxi, that is, up to the present day, because although since the 1980s postmodern art has questioned the validity of modernity, historians disagree, and there are even experts —such as Valeriano Bozal— who point out that postmodernity is just one more phase of modernity, precisely the one in which it reflects on itself.

History

The origins of rationalism are diffuse and come from a slow evolution from the middle of the XIX century until the 1920s, in that a new generation of architects, critics and architecture scholars began to realize that the achievements of that time shared some common stylistic traits and a modern and dynamic program for the construction and urban processes. In the genesis of rationalism are the technological advances that led to the architecture of glass and iron in the second half of the XIX century, the Arts & Crafts, the construction of the first skyscrapers promoted by the Chicago School, the formulation of functionalist theory by Louis Sullivan, some postulates of modernist architecture —especially the Viennese Sezession— and the work of various individual architects —in especially Frank Lloyd Wright—until leading to the avant-garde currents of the early XX century, which are usually considered as pre-rationalism.

It must also be considered as the driving force behind the new architecture in the transition between the 19th century and xx the technological changes produced in the so-called Second Industrial Revolution, such as the invention of reinforced concrete (1854), the Bessemer process for making steel (1856), the invention of the dynamo to generate electricity as driving force (1869), the telephone (1876), Galileo Ferraris's experiments on the rotating magnetic field that allow the remote transport of hydraulic energy (1883), the electric light bulb (1879), the internal combustion engine (1885), etc. All these factors helped the construction industry and launched architecture into a new way of building with multiple possibilities.

A first determining factor in the appearance of rationalism was the opening in 1919 of the Bauhaus, a school of architecture, art and design directed by Walter Gropius that advocated a functionalist style of simple lines and based on industrial production. During the years after the end of the First World War, several architects who promoted rationalist premises in their works began to stand out, such as Gropius himself, Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, considered the greatest exponents of this movement, who helped to its international diffusion. Little by little, the new style spread thanks to competitions, congresses and exhibitions: in 1922, the competition for the new headquarters of the Chicago Tribune revealed proposals by Gropius, Adolf Meyer, Max Taut and Hans Scharoun; in 1925, Le Corbusier built for the Exposition of Decorative Arts and Modern Industries in Paris the pavilion of L & # 39; Esprit Nouveau , in which he exposed his new urban planning theories; in 1927, the exclusion of Le Corbusier from the competition for the headquarters of the League of Nations in Geneva caused a great scandal, a fact that had repercussions in giving him more fame; Also in 1927, Mies van der Rohe organized an architecture exhibition dedicated to housing (Die Wohnung) in Stuttgart, which promoted the construction of thirty-two houses —the Weißenhofsiedlung development—, including buildings and single-family homes., which was a major milestone for the new style: the internationality of the project led Professor Paul Schmitthenner to state that "we are reaching the international style formula of the century XX». Other exhibitions in which rationalist architects participated were: the International Exhibition of Barcelona (1929); the Hall of Decorating Artists of the Grand Palais in Paris (1930); and the Baauausstellung (Construction Fair) in Berlin (1931).

The biggest event that led to the officialization of rationalism was the founding in 1928 in La Sarraz (Switzerland) of the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM), an international association of architects in charge of holding congresses to debate the new principles of architecture and help its international diffusion.

Another major event that helped spread the new style was the Modern Architecture - International Exhibition exhibition, organized by Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson at the MoMA in New York in 1932, of which also gave rise to the book published by both, The International Style: Architecture since 1922, which contributed the term International Style to designate the movement. These authors focused more on the formal aspects that united the various manifestations of this movement than on its theoretical and even utopian premises. They pointed out as the main characteristics of this style the rejection of historicist eclecticism, the use of materials such as steel, glass and concrete, the use of the open plan and the "conception of architecture as volume rather than mass".

Rationalism spread rapidly throughout Europe and took root especially in Germany, France, the Netherlands, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Switzerland, the United Kingdom —thanks especially to German architects who fled Nazism—, Italy and Spain. In the 1930s, rationalism had a new dissemination center in the United States, where numerous European architects exiled because of German Nazism, Italian Fascism and Soviet Communism arrived. However, in that decade the movement entered a phase of certain doubts and criticism of his excessive formalism and his cold mechanism, far removed from human needs. Le Corbusier himself distanced himself from his initial purism and began to consider the machine as a tool and not an end in itself. Despite everything, rationalism continued to be the hegemonic style at the international level until practically the 1960s.

After World War II the movement began to decline, but it continued to be built in a rationalist style until the 1960s and even 1970s, in coexistence with other new styles that were emerging. In fact, in the postwar period the urgency of Reconstructing the cities devastated in the conflict contributed to the survival of the style, since in the face of the search for new styles, an already consolidated one was preferred. This occurred in parallel to the definitive universalization of the rationalist language, since its greatest diffusion in those years occurred in emerging countries such as Brazil, India, Mexico and Venezuela. This globalization of the movement led to its diversification, since it had to adapt to the different construction traditions of countries with very diverse cultures, as well as to different climatic, economic, and social conditions. Even in the United States, the International Style gradually became regionalized, as demonstrated by the substitution in numerous cases of the skeletons of steel for wood, influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian houses.

The spread of internationalism after the war was mainly carried out by the International Union of Architects (Union Internationale des Architectes, UIA), founded by the Frenchman Pierre Vago in collaboration with the Englishman Patrick Abercrombie, the Italian Saverio Muratori, the Portuguese Carlos João Chambers Ramos and the Russian Viacheslav Popov; Vago was its general secretary between 1948 and 1968. The first congress was held in Paris in 1948 and since then every three years in a different country. Another source of dissemination was the Architectural Review magazine, as well as institutions such as Harvard University, the Ulm Bauhaus and the Architectural Association School of Architecture in the United Kingdom, and other newly created ones such as the Middle East Technical Ankara University and the Asian Institute of Technology in Bangkok.

However, after the world war, the International Style gradually became a method of systematic construction and lost some of its initial essence and its utopian component of an art at the service of society. Confidence in the new technologies, in art as an educational instrument for the people, in a universal aesthetic that entailed a universal ethic, were gradually diluted, and the movement was reduced to a regulated style, which left no room for innovation. nor individual creation, for subjectivity or the relationship with nature. His stylistic evolution was towards a certain eclecticism —according to Jürgen Joedicke— or mannerism —according to Josep Maria Sostres—, with two possible ways of realization: “mechanical imitation and impersonal of great examples» (Sostres) or regionalist contextualization, such as that practiced by Scandinavian neoempiricism, British brutalism, Italian neorealism and neoliberty or the Barcelona School in Spain.

The beginning of the end of this movement was staged in the IX CIAM congress, in which a group of dissident architects organized themselves into the so-called Team X, which advocated an evolution towards a more realistic and socially useful style, which it materialized in a new style called brutalism. This group accused CIAM of having sponsored the International Style by imposing «mechanical concepts of order», without taking into account the emotional needs of the human being or the territorial specificities of the various countries in which the style was developed. Philip Johnson himself confessed in 1996 that "our so-called modern architecture was too old, icy and flat".

Although the end of rationalism as a style can be placed in the first five years of the 1960s, it should be noted that until the 1970s and early 1980s this style was still built —in a more or less orthodox way— in many parts of the world, especially in emerging countries that had arrived with some delay to modernity. The decolonization process that began in Africa and Asia after the Second World War led to the construction boom in these new countries, which needed new infrastructures and government buildings, and which adopted the International Style as a way of equating the construction of a new state with a modern image. and progressive. In many cases, this architecture turned out to be stereotyped and out of context, with a certain appearance of transplanting Western typologies to countries with different cultural traditions, without taking into account the social, geographical and economic conditions of these countries.

CIAM

The International Congress of Modern Architecture (in French: Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne) was founded in La Sarraz (Switzerland) in 1928 to foster interrelation between architects and urban planners from all over the world in order to exchange ideas and compare the styles and techniques used in different parts of the world. Originally, the meeting was motivated as a reply to the postponement of the Modern Movement in the competition for the headquarters of the League of Nations in Geneva, against which the architects of the new movement wanted to offer a common front. CIAM's founders included Le Corbusier, and Siegfried Giedion was its first secretary until 1956. CIAM's executive body was instituted CIRPAC, the International Committee for the Resolution of Problems in Contemporary Architecture (French: Comité International pour la Résolution des Problèmes de l'Architecture Contemporaine). In 1959 its definitive dissolution took place; by then the congress had more than thirty affiliated countries and some three thousand members.

Four phases are usually pointed out in the history of CIAM: the founding cycle of congresses (1928-1933), the crisis caused by Nazism and the series of emigrations of numerous architects (1934-1945), the refounding and expansion of the congress (1945-1953) and the process of agony of the movement motivated by the protest process of the youngest architects (1953-1959).

In their first meeting, Le Corbusier was in charge of drafting the agenda to be discussed, which included the following topics: modern technology and its consequences; standardization; the economy; the urban; youth education; realization: architecture and the state. A statement was drafted which argued that "in order to benefit a country, architecture must be intimately related to the general economy. The true performance will be the result of rationalization and normalization, and sufficient production to fully satisfy human demands." Three functions were also identified as primary objectives of urban planning: living, working, entertaining.

In 1929 the second congress met in Frankfurt (Germany), focused on the question of «minimum housing». CIAM III took place in 1930 in Brussels (Belgium), on the "rational urbanization" of space. The fourth congress, dedicated to the "functional city", was to be held in Moscow, but for political reasons it was finally held in Athens (Greece) in 1933, aboard the yacht Patris II; in it the so-called Athens Charter was agreed upon. In 1937, CIAM V was held in Paris (France), under the premise of "housing and leisure". World War II paralyzed the congresses and fostered the rise of the American group; Josep Lluís Sert, exiled in that country, published in 1943 the book Can Our Cities Survive? , where he collected the postulates of CIAM and became the reference work of rationalism in the Anglo-Saxon sphere. After the war CIAM expanded to Asia, Africa and Latin America, and the Le Corbusier-Gropius-Giedion trio began to lose influence. In 1947 CIAM VI took place in Bridgwater (England), focused on the reconstruction of cities devastated by war. CIAM VII took place in Bergamo (Italy) in 1949, on architecture as art. In 1951, CIAM VIII was housed in Hoddesdon (England) and dealt with the center of the city, with a first split between orthodox and renovating positions due to the approach of new concepts such as the symbolic dimension and the human scale. CIAM IX took place in 1953 in Aix-en-Provence (France) and focused again on generational disputes and the founding of Team X by Jaap Bakema, Georges Candilis, Aldo Van Eyck and Alison and Peter Smithson.. In 1956 CIAM X was held in Dubrovnik (Yugoslavia), focused on the Habitat Charter as an alternative to the Athens Charter. In 1957 the national groups were dissolved and Jaap Bakema was elected General Secretary. The last congress, CIAM XI, took place in 1959 in Otterlo (The Netherlands) and meant the dissolution of CIAM.

The 1932 MoMA Exhibition

The exhibition Modern Architecture - International Exhibition was held at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York from February 9 to March 23, 1932. It subsequently toured the United States for six years. Its curators were the critic Henry-Russell Hitchcock and the architect Philip Johnson, who chose the most representative works of the new style in Europe and the United States —with the only exception outside these continents of the building of the electricity laboratory of the ministry of Public Works in Tokyo, by Mamoru Yamada. The selection criteria were basically aesthetic, which is why they left aside the more programmatic aspects of the new architecture, especially its social and economic dimensions, a fact for which Hitchcock and Johnson's proposal was criticized. According to the curators, the works included in the new trend had to meet a series of parameters, such as the absence of ornamentation, the composition in terms of volume and not mass, modular regularity and not axial symmetry. As for architects, they left out the work of the movement's pioneers, such as Peter Behrens, Auguste Perret, Adolf Loos, Antonio Sant'Elia and Frank Lloyd Wright, and established Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, as paradigms of the new movement. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Jacobus Johannes Pieter Oud, Gerrit Rietveld and Richard Neutra.

The work of sixty-seven architects was exhibited. Most of the projects on display came from Germany, followed by the United States. By architects, the majority were projects by Gropius, Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe. The selection was made by the curators themselves, whether they were projects that were familiar with both or one of them, with few exceptions from recommendations from other people they trusted, such as Richard Neutra, who recommended Mamoru Yamada's Tokyo electrical laboratory, or Bruno Taut., who advised the Moscow electrophysical laboratory, Ivan Nikolayev and Anatoli Fisenko.

With the same premises as the exhibition, Hitchcock and Johnson published the same year the book The International Style: Architecture since 1922, which gave its name to the movement in the Anglo-Saxon world. In the book they analyzed the work of seventy-two architects from fifteen countries, with the premise that they represented a new international architectural style. In the foreword, MoMA director Alfred Barr noted that the authors had shown that "today there is a modern style as original, consistent, logical and international as any of the past".

In 1951, Hitchcock made the following retrospective analysis of the parameters used for exposure:

Too few in number and too narrow, I would say in 1951 that they are the principles that we so firmly stated in 1932. Today it would add a third principle: the articulation of the structure and omit the reference to the decoration, which constitutes a more than formal aesthetic issue. The concept of regularity is too negative to explain the best contemporary design, although I cannot find a phrase that explains globally the most positive qualities of modern design.

Philip Johnson also revised the parameters of the exhibition in the 1960s and pointed out as the main characteristics of the International Style the structural honesty, the repetitive modular rhythms, the flat ceilings, the clarity expressed by the glass surfaces, the box as a container and the absence of decoration.

General characteristics

Rationalism was a heterogeneous movement with both geographical and chronological origins difficult to pin down. It could be said that it was rather a confluence of different styles that converged on common characteristics, which became more clearly evident after the First World War. Its general characteristics were forged little by little in the work and contributions of all the movements and architects that are considered precedents of this style. When these characteristics were more thoroughly analyzed, it was possible to determine that the majority of the creations of this new style were based on several main points: use of a functionalist language, use of simple geometric shapes and regular structures, a tendency towards a vertical-horizontal arrangement, resignation to the ornamentation and use of industrial-type materials (concrete, steel, glass). Despite this, it is difficult to speak of a homogeneous style and, in fact, many rationalist architects affirmed that they did not have a style, but that theirs was "a purely rational form of design".

The ideological postulates of rationalism were based on progress and modernity, with a firm commitment to industrial and mechanized production, as well as a rational organization of work. With a tendency towards a progressive and egalitarian political ideology, they wanted to develop a new constructive language that would serve to renew society, which was especially reflected in their interest in urban planning and social housing. Thus, it could be said that the foundations of rationalism are found in the "reconciliation between technological progress and social commitment", according to Jeremy Melvin.

One of the main premises of the Modern Movement was functionalism, the subordination of architectural language to its function, leaving aside any aesthetic or accessory consideration for the main objective of construction: "form follows function", according to Louis Sullivan's words. Thus, any constructive form must be a reflection of the use for which it has been conceived. According to this theory, even the construction elements —such as beams and pillars— must be left in sight, since they are part of the formal design according to which a structure is planned. For this, industrial production and technological advances must contribute, which are tools made available to the architect to optimize his constructive work.

In the heart of industrial society and the capitalist economy, the rationalist architect was required to achieve maximum functionality and optimization of resources, to elaborate the best designs with the most economical industrial criteria; he had to consider all the components of life in society, for which he had to take responsibility "from the spoon to the city", as they used to say at the time. In general, most rationalist architects had social concerns and considered it a duty of the State to guarantee minimum living conditions (Existenzminimum) to the population. In rationalism, all the constituent elements of the architectural work were subordinated to function, so function and style are equated.

Among the main stylistic features of rationalism are: rectilinear and orthogonal forms, composition in volume rather than mass, uniform and visible structures, absence of axial symmetry, the use of pilitis as support of the structure, flat roofs, empty central patios, open plan indoors, use of overhangs —especially on balconies and terraces—, facades without decorations, white walls and rectangular windows, linked in an elongated band running along the plane of the facade. The use —especially in skyscrapers— of the curtain wall (curtain wall), a type of self-supporting glazed façade, independent of the resistant structure of the building, generally built by repeating a pattern, is also characteristic. modulated prefabricated element, which is usually composed of an extruded aluminum frame and a glass panel. Another commonly used element is the brise soleil, a type of sun protection for windows and balconies, as a blind or lattice, which can be made of various materials, from wood to the concrete commonly used by Le Corbusier. It should be noted that rationalist architecture received a certain influence from nautical design, and even Le Corbusier added numerous photographs of ships and ocean liners in his book Vers une Architecture (1923).

The main aesthetic factor of the new style was the absence of applied decoration, conceived as a way of eliminating superficiality. The new premise was simplicity, based mainly on industrial materials, a structural order based on regularity versus angularity and a harmony based on proportion and geometry, and a design centered on a skeleton of columns (concrete pillars or metal) instead of a mass structure, with a smooth and seamless surface, made of smooth materials —preferably metal and glass—, with windows that do not interrupt the perfection of the façade, preferably with light metal frames, and a Chromatism focused on the natural color of the material. They also considered relevant the choice of the place to be built and its relationship with the environment, within which the external walls of the building —such as terraces and pergolas— are considered extensions of it, as well as the walls and paths of the gardens, whose rectilinear planimetry contrasted with the work of nature. On the other hand, within the ornamental aspect, they considered the inclusion in the building of paintings and sculptures as independent elements that should not degenerate into simple decoration, but should embellish independently. In this sense, Hitchcock and Johnson pointed out abstract wall paintings as the ideal complement to modern architecture.

Rationalist architecture —especially design— maintained close contacts and influences with the rest of the arts, especially painting, and within this the vanguards such as neoplasticism, suprematism and constructivism, all of them with an abstract trend, from which they took some of their designs and the preference for primary colors, as well as experimentation with various materials and a design based on basic and proportionate forms. Some of the painters who most influenced the movement were professors at the Bauhaus or had contacts with this institution, such as El Lissitzky, Theo van Doesburg, Wassily Kandinski, Paul Klee, Johannes Itten and László Moholy-Nagy.

Theory and criticism

Rationalism was nourished by an extensive theoretical corpus prepared by some of its most prominent representatives, such as Gropius and Le Corbusier. In 1925, Gropius published Internationale Architektur, where he related his work to that of other architects such as Le Corbusier, Oud and Wright, noting that they all shared a functional vision of architecture, with a logical conception of architecture. work and an economic planning of optimization of money, materials, time and space. He also noted that "the uniformity of appearance of modern buildings, born of world travel and technology, overcomes the natural boundaries that continue to isolate individuals and peoples, creating a bridge between all cultural regions."

Le Corbusier published several books on art and architecture, such as Vers une Architecture (1923), L'Art Décoratif d'Aujourd'hui (1926) and Urbanisme (1925), in addition to publishing the magazine L'Esprit Nouveau (1920-1925) with Amédée Ozenfant. In his 1923 book he presented his theoretical principles in a series of texts with a somewhat provocative tone, with the aim of opening "unseeing eyes" towards modern architecture. He uses a concise style, with short and simple sentences, to establish clear premises that serve as a guide for the architect, with poetic similes and abundant graphic material. The content focuses on the aesthetic reform of architecture produced since the mid-XIX century, as well as concepts such as functionalism and industrial design; he speaks of the hygienic and moral qualities of architecture, which he symbolizes in an ocean liner: "a pure, clean, clear, neat and healthy architecture." However, he believes that the styles are "a lie", although he recognizes the artistic nature of architecture, since beyond the simple rational function the architect configures an aesthetic to the building. Regarding his treatise on urban planning, he analyzes it from a functional perspective, in which the city is a work tool, and defends some general lines based on order and linearity, which will be specified in the Charter of Athens (1943).

Critics and art historians such as Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Siegfried Giedion and Nikolaus Pevsner also contributed to the movement's theoretical corpus. Hitchcock made his first contribution to the International Style in an article in the magazine Hound and Horn in 1928, which was followed by the book Modern Architecture, Romanticism and Reintegration (1929), where he stated that the new style was "a distinct branch of modern architecture influenced by cubist and neoplastic painting." But his most relevant work was The International Style: Architecture since 1922 , prepared with Philip Johnson for the 1932 MoMA exhibition. In it they established the defining parameters of the movement, noting that:

Today a modern style has been born... This contemporary style, which exists worldwide, is unitary and inclusive... The concept of style as a potential development framework has emerged from the recognition of underlying principles... In enunciating the general principles of contemporary style, as in analyzing its structural origin and its modification due to function, it is difficult to avoid a certain appearance of dogmatism. Against those who claim that a new architectural style is something impossible or undesirable, it is necessary to insist on the coherence of the results obtained within the spectrum of possibilities so far explored. And it is that the International Style already exists at the present time; it is not simply something that the future may depart from us. Architecture is always a set of real monuments, not an imprecise theoretical body.

The book about the exhibition contains a short text and abundant illustrations. It was written entirely by Hitchcock, since Johnson's participation consisted only in its correction. His thesis focuses on the verification of a new architectural style contemporary to the date of the exhibition, with Gropius, Oud, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Rietveld and Mendelsohn as main representatives. He establishes the beginnings of this style after the First World War and points to architects such as Peter Behrens, Otto Wagner, Auguste Perret and Frank Lloyd Wright as precedents, whom he describes as "semi-modern".

Giedion presented his ideas preferably in Space, Time and Architecture. The Growth of a New Tradition (1941), which marked the historical image of modern architecture in Europe and the United States. It is a compendium of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures that he gave at Harvard University between 1938 and 1939. Giedion's main goal was to integrate modern architecture into art history, as well as establish its theoretical bases in a scientific context. He pointed to modern art and architecture as interdependent units and considered the opposition between science and art to be over. Just as Hitchcock established the aesthetic principles of rationalism, Giedion also sought to establish the structural principles of it, analyzing the formal qualities of the movement to find the underlying ideas. He points to the birth of modern architecture in industrialization and advances in engineering, and as pioneers to Victor Horta, Hendrik Petrus Berlage, Otto Wagner, Auguste Perret, and the Chicago School. He recognizes a fundamental role for Frank Lloyd Wright, but reserves the role of "heroes" of modern architecture for Gropius and Le Corbusier - Mies van der Rohe did not cite him until a reissue in 1954 -. Giedion's work was the basic manual of modern architecture until practically the 1980s and marked the conscience of two generations of architects.

Pevsner was a German historian and critic based in the UK from 1935. In Pioneers of the Modern Movement (1936, later titled The Sources of Modern Architecture and Design), introduced the term "Modern Movement", which he considered the "proper" style for the 20th century, a style functional that responds to the new needs of the masses. Pevsner advocated a strict, anonymous, impersonal internationalism that leaves "less room for self-expression" and that adapts to the new "basic social conditions." Throughout his literary production, he elaborated a history of global, social and cultural architecture, detached from personalities and focused on the notion of style, with the intention of differentiating "true styles" from "transitory fashions".

Other books on the modern Movement were: Internationale neue baukunst by Ludwig Hilberseimer (1926), Die Baukunst der neuesten Zeit by Gustav Adolf Platz (1927), Moderne Architektur und Tradition by Peter Meyer (1928), Die neue Baukunst in Europa und Amerika by Bruno Taut (1929), Les tendances de l'architecture contemporaine by Myron Malkiel-Jirmounsky (1930), The New World Architecture by Sheldon Cheney (1930), La nuova architettura by Fillia (pen name of Luigi Colombo, 1931), Gli elementi dell'architettura razionale by Alberto Sartoris (1932), etc. It is also worth noting the magazines that spread the new style, such as Die Form, Das neue Frankfurt, L'architecture d'aujourd'hui , The Beautiful House, Moderne Bauformen, Wasmuth Monatshefte für Baukunst und Städtebau and The Architectural Review.

The first voices critical of the Modern Movement arose from brutalism in the 1950s and developed in the 1960s with the work of historians and critics such as Reyner Banham and Manfredo Tafuri. Banham was a student of Giedion and Pevsner and, with a view to his doctoral thesis, was invited by the latter to analyze the Modern Movement from where he had left it, of the pioneers who laid the foundations of this style between the end of the century XIX and early xx. Banham carried out this exercise (Theorie and Design in the First Machine Age, 1960), but he did it from a critical, demystifying perspective; Comparing modern theories with practical achievements to check if they actually met the premises, he nevertheless showed that in most cases the supposed functionalism defended by rationalist architecture was instead translated into a certain formalism. Faced with this, he advocated a "second age" dominated by the machine and mass consumption, and became the main defender of the style heir to rationalism: brutalism. Tafuri, a disciple of Giulio Carlo Argan and influenced by Marxism, structuralism, semiology and psychoanalysis, conceived architecture as a part of the history of work, of production mechanisms. In Teorie e storia dell'architettura (1968) he criticizes the optimism typical of avant-garde architecture and offers a more pessimistic vision, in which architecture is an ambiguous and changing process, “a perpetual contestation of the present». Also in Progetto e utopia (1973) he again criticizes modern architecture and points out the need to “destroy the powerful and ineffective myths that still fascinate architects”.

Background

The architecture of the early 20th century was born with a willingness to break with the past, especially as opposed to the historicism that practiced since the middle of the XIX century, an academic style based on classical premises and on the reinterpretation of styles from the past: neo-Romanesque, neo-Gothic, neo-baroque, etc. An early influence of the new movement was that of modernism—known as art nouveau in France, Modern Style in the UK, Jugendstil in Germany, or Jugendstil in Germany. i>Sezession in Austria—, a style that sought to renew the architectural language and that provided some of the initial premises of the Modern Movement, although its excessive decorativeness was rejected by the rationalists. The artistic avant-gardes prior to the First World War, such as expressionism and futurism, were nourished from this style, movements that have sometimes been described as pre-rationalism. After the world war ended and until the mid-1920s, movements such as neoplasticism (De Stijl), the expressionism of the New Objectivity or constructivism evolved from those initial premises towards a greater formalism that already pointed to the International style, which was forged in the Bauhaus School and in the foundation in 1928 of CIAM (International Congress of Modern Architecture).

First of all, it should be noted as an immediate antecedent of rationalism the new architecture practiced in the XIX century based on advances technologies fostered by the Industrial Revolution, which were reflected in various typologies such as architecture in iron or glass and iron. It should be borne in mind that the new industrial era brought with it new problems and approaches in the construction and urban areas, since technical, economic and social progress led to the appearance of new needs such as railway stations, bridges and viaducts for new media. of transport, changes in cities due to population increases that demanded new infrastructures and a whole series of new needs that architecture and engineering had to face. These needs led to a faster and cheaper type of construction, with more daring solutions and far from academic architecture. A good example were the cast iron constructions, developed by architects and engineers such as Hector Horeau, Henri Labrouste, William Fairbairn and James Bogardus. A dynamic factor of this new type of architecture were the trade fairs known as Universal Expositions, which due to their ephemeral nature fostered a type of construction of modular forms using prefabricated elements. The first, the Great London Exhibition of 1851, was notable for Joseph Paxton's The Crystal Palace building, made of glass with a metal structure. The paradigm of this type of construction was the Eiffel Tower, built by the engineer Gustave Eiffel for the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1889.

Throughout the XIX century, a new way of conceiving design and construction was developed based strictly on the reason and scientific criteria, which subordinated the shape of the building to its function: functionalism, also called “architectural or structural rationalism”. For this new generation of architects, their main tool was applied mathematics and their fundamental objective was the calculation of the lines of force in the structure of a building. Among its main representatives are: Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, Henri Labrouste, Gottfried Semper, Augustus Pugin, Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Anatole de Baudot and Hendrik Petrus Berlage.

Another influence on modern architecture was William Morris and the Arts & Crafts (Arts and Crafts), emerged in the United Kingdom around 1860 and lasted until 1910. This current defended a revaluation of craft work and advocated a return to traditional forms of manufacturing; it stipulated that art should be as useful as it is beautiful, with an ideal of beauty based on purity and simplicity. The greatest architectural exponent of this movement was the Red House, Morris's own house, built in 1859 by Philip Webb in Bexley Heath (Kent), made of red brick with a fluid design, without prominent facades, using traditional techniques; Morris designed the garden and the decoration was carried out by Morris, Webb and the Pre-Raphaelite artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, in an ensemble that was classified as a "complete work of art". Other architects of this movement such as Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo and Charles Francis Annesley Voysey finished laying its programmatic foundations: design subject to function, prevalence of vernacular styles and native materials, freedom of style and integration of the building into the landscape.

Another of the precedents of rationalism was the so-called Chicago School, developed in the US city of Chicago between 1875 and 1900, and which stood out for being the promoter of a new type of building: the skyscraper. At that time, the city was growing at a dizzying rate thanks to its thriving economy, so the buildings had to be fast, which is why architects adopted iron engineering techniques. On the other hand, the speculative process of building land made it necessary to build at a height to make the investment profitable —a fact fostered by the invention of the elevator in 1853—. Thus, a series of large buildings in the functional style appeared, built by architects such as William Le Baron Jenney, Daniel Burnham, John Wellborn Root, William Holabird, Martin Roche, Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan. The latter coined the famous phrase "form follows to function", the main aphorism of functionalism.

The Austrian Sezession, the local variant of modernism, also initiated a path towards rationalism —especially Germanic—. Although international modernism was a renovating movement and opposed to academic historicism, which was committed to integral design and the use of new materials and technologies, its excessive decorativeness distanced it from the postulates of rationalism; however, the Austrian variant —like the Scottish one represented by the Glasgow School— had a more geometric and rectilinear component that did influence the appearance of Germanic rationalism. Its first exponent was Otto Wagner, professor at the Academy of Vienna who instilled in his students modernity as a starting point for artistic creation, and who was interested in the use of new materials and urban planning approaches in line with the new times, as can be seen in his reform of the Karlsplatz in Vienna or his project of metropolitan with overpasses and stations of modern design. Joseph Maria Olbrich (Vienna Sezession building, 1898) and Josef Hoffmann (Stoclet Palace in Brussels, 1905-1911) followed in their footsteps. In 1903, Hoffmann and Koloman Moser founded the Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese Workshops), a close association to the Arts & Crafts which aimed to bring the industry closer to the world of applied arts.

In the field of urbanism, the theories of Ebenezer Howard and his idea of the garden-city were essential for the rationalist proposals, a type of urban entity of residential areas separated by large green areas and connected by large radial avenues, with a center neuralgic that would bring together the buildings for administration, finance, services, education, health, culture and other sectors.

Lastly, it is worth remembering the work of various architects who, in reaction to the excessive decorativeness of art nouveau, developed in the first decade of the century XX a more sober style based on classical shapes but without falling into the stagnant language of academic neoclassicism, but with modern solutions that largely pointed to rationalism. This style is sometimes defined as "modern classicism" or "primitive rationalism" and its greatest representatives were: Tony Garnier, Auguste Perret, Adolf Loos and Peter Behrens. The first was an architect and urban planner, the first to propose a global model of industrial city (Une Cité Industrielle, 1917) in which life and technique are combined, with an in-depth study of urban functions and the adaptation of each element to its function. Most of his works are in Lyon: market and slaughterhouse (1908-1924), Grange Blanche Hospital (1911-1927), Municipal Stadium (1913-1918), United States neighborhood (1920-1935). Perret stood out for his use of concrete both as a constructive and expressive element, generally with large stained glass windows in the spaces between and with a complete absence of ornamentation: house on Rue Franklin in Paris (1903), garage on Rue Ponthieu (1905), church of Notre- Dame de Le Raincy (1922-1923). Loos received the initial influence of Otto Wagner's secessionism, but moved away from it due to his fear of confining himself to a style of marked guidelines and excessive originality, in search of a greater simplicity far from any ornamentation. He took from the Arts & amp; Crafts his commitment to craftsmanship and a more human component in the construction process. His works include: the apartment building on the Michaelerplatz in Vienna (1909-1911) and the Steiner (1910) and Scheu (1912), also in Vienna. Behrens opted for an architecture with simple, austere and functional lines, with the use of new materials and technologies, with a certain influence from William Morris. Director of the General Electricity Company AEG of Berlin, he built for it a series of factories and buildings where he anticipated many of the structural solutions of rationalism, among which the turbine hall (1909) stands out.

Pre-rationalism

Expressionism

Expressionism was a cultural movement that emerged in Germany at the beginning of the XX century, which was reflected in a large number of fields: plastic arts, architecture, literature, music, cinema, theater, dance, photography, etc. Expressionist architecture developed mainly in Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Denmark. It was characterized by the use of new materials, sometimes caused by the use of biomorphic forms or by the expansion of possibilities offered by the mass production of construction materials such as brick, steel or glass. Many Expressionist architects fought in World War I, and their experience, combined with the political and social changes brought about by the German Revolution of 1918, led to utopian perspectives and a romantic socialist program. Strongly experimental in nature, the expressionists' works stand out for their monumentality, the use of brick and the subjective composition, which gives their works a certain air of eccentricity. The main expressionist architects were: Bruno Taut, Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn, Hans Poelzig, Hermann Finsterlin, Fritz Höger and Hans Scharoun.

Expressionist architecture developed in Germany in various groups, such as Deutscher Werkbund, Arbeitsrat für Kunst, Novembergruppe and Der Ring ; Also noteworthy in the Netherlands is the Amsterdam School. The Deutscher Werkbund (German Labor Federation) was founded in Munich in 1907 by Hermann Muthesius, Friedrich Naumann and Karl Schmidt, and later included figures such as Walter Gropius, Bruno Taut, Hans Poelzig, Theodor Fischer, Wilhelm Kreis, Richard Riemerschmid, and Bruno Paul. Heir to the Jugendstil and the Sezession, and inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement, its objective was the integration of architecture, industry and crafts into through professional work, education and advertising, as well as introducing architectural design into modernity and giving it an industrial character. The main characteristics of the movement were the use of new materials such as glass and steel, the importance of industrial design and decorative functionalism. This group was the one that organized an exhibition in Stuttgart in 1927 for which they built a large housing colony, the Weißenhofsiedlung, designed by Mies van der Rohe and buildings built by Gropius, Behrens, Poelzig, Taut and others, together with architects from outside Germany such as J.J.P. Oud, Le Corbusier and Victor Bourgeois. This exhibition was one of the starting points of the new architectural style that was beginning to emerge.

Parallel to the German Deutscher Werkbund, between 1915 and 1930 a notable expressionist architectural school developed in Amsterdam (Netherlands). Influenced by modernism -mainly Henry Van de Velde- and by Hendrik Petrus Berlage, they were inspired by natural forms, with imaginatively designed buildings where the use of brick and concrete predominates. Its main members were Michel de Klerk, Piet Kramer and Johan van der Mey, who worked together countless times, contributing greatly to the urban development of Amsterdam, with an organic style inspired by traditional Dutch architecture, in which the wavy surfaces.

The Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Council of Art Workers) was founded in 1918 in Berlin by the architect Bruno Taut and the critic Adolf Behne. Emerged after the end of the First World War, its objective was the creation of a group of artists that could influence the new German government, with a view to the regeneration of national architecture, with a clear utopian component. His works stand out for the use of glass and steel, as well as for the imaginative forms charged with intense mysticism. They immediately recruited members from the Deutscher Werkbund, such as Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn, Otto Bartning and Ludwig Hilberseimer. After the events of January 1919 related to the Spartacus League, the group renounced its political aims and dedicated itself to organizing exhibitions. Taut resigned as president and was replaced by Gropius, although the group was finally dissolved in 1921. Linked to this was the group Novembergruppe, which emerged in 1918 and was active until 1933, with the aim of using art and architecture to improve the world. Walter Gropius, Hugo Häring, Erich Mendelsohn and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe were in their ranks.

The Der Ring (The Circle) group was founded in Berlin in 1923 by Bruno Taut, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Peter Behrens, Erich Mendelsohn, Otto Bartning, Hugo Häring and several other architects, to which Walter Gropius, Ludwig Hilberseimer, Hans Scharoun, Ernst May, Hans and Wassili Luckhardt, Adolf Meyer, Martin Wagner, etc., were soon added. His goal was, as in previous movements, to renew the architecture of his time, with special emphasis on social and urban aspects, as well as research into new materials and construction techniques. Between 1926 and 1930 they carried out notable work in the construction of social housing in Berlin, with houses that stand out for their use of natural light and their location in green areas, among which the Hufeisensiedlung (Cologne of the Horseshoe, 1925-1930), by Taut and Wagner. Der Ring disappeared in 1933 after the rise of Nazism.

The last phase of German expressionism was the so-called Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), a mostly pictorial movement that had a translation to architecture based on a rational and objective conception of it, as well as in the architect's social commitment. This movement materialized in the Neues Bauen (New Construction) association, which included Bruno Taut, Erich Mendelsohn and Hans Poelzig.

Cubism

Cubism (1907-1914) was an artistic movement based on the distortion of reality through the destruction of spatial perspective of Renaissance origin and, instead, the organization of space according to a geometric pattern and vision objects simultaneously. Although it occurred essentially in plastic arts, it had some manifestation in the field of architecture, especially in Czechoslovakia. Its main representative was Josef Gočár, who after a few beginnings influenced by the work of Josef Hoffmann, in 1911 joined the Group of Fine Artists (Skupina Výtvarných Umělců) and began working in the Cubist style, as denoted in the house of the Black Madonna in Prague (1911–1912) and the thermal establishment of Lázně Bohdaneč (1912-1913).), where he combines classical and modern forms with pyramidal cubism. After the First World War and the independence of Czechoslovakia, he began with Pavel Janák the search for a national Czech architectural style, which was reflected in the so-called "rondocubism", which incorporates rounded and multicolored shapes from the bohemian-moravian vernacular decoration, as evidence his Legion Bank in Prague (1921-1922). From 1923 his style evolved towards a functionalism of neoplastic influence.

Other representatives were: Pavel Janák (Jakubec villa in Jičín, 1911-1912; Drechsel villa in Pelhřimov, 1912-1913; Pardubice crematorium, 1921-1923; Adria palace in Prague, 1922-1925); Josef Chochol (Kovařovic villa in Prague, 1912-1913; Bayer and Hodek residential buildings in Prague, 1913-1914);

Futurism

Futurism (1909-1930) was an Italian artistic movement that exalted the values of technical and industrial progress of the XX century, which highlighted aspects of reality such as movement, speed and the simultaneity of action. Although it occurred especially in plastic arts, it also had some approach in architecture, although the utopian nature of its formulations prevented its material realization in many cases. The figure of Antonio Sant'Elia stood out, who in 1914 presented his model of a futuristic city, characterized by tall skyscrapers, streets at different levels and new types of buildings, such as stations and power plants. In 1914 he signed the Manifesto of Futurist Architecture, where he proclaimed that architecture "must be preserved as art, that is, as a synthesis, as an expression". Sant'Elia was joined by the architect Mario Chiattone and together they exhibited drawings of their dream city of the future, the Città nuova (new city). Died in 1916, Sant'Elia could not carry out his projects, but his theoretical work influenced the construction of the FIAT workshops of Giacomo Mattè-Trucco in Turin (1915-1921), with flat concrete roofs where the cars ran over the workshops.

Neoplasticism (De Stijl)

Neoplasticism (1917-1932), also known by the Dutch name De Stijl (“the style”), was also an interdisciplinary movement that excelled in painting with figures such as Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg, with an abstract style, while in architecture a style marked by geometric compositions and objective and innovative solutions developed, greatly influenced by the work of Hendrik Petrus Berlage. They are works that stand out for their smooth surfaces and their breakdown into planes, vertical and horizontal lines, with the use of color as an element that emphasizes the structure, generally primary and flat colors. Some of their stylistic hallmarks, such as flat ceilings, smooth walls and free and flexible interior spaces were later characteristic of the International Style.

The most paradigmatic work of this style was the Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht (1924), by Gerrit Rietveld and Truus Schröder, whose structural solutions largely indicated the main characteristics of the International Style: asymmetrical composition, geometric shapes without relief, flat roofs with overhangs at the corners, absence of ornamentation, longitudinal windows and a preference for the color white. This new way of understanding architecture was translated into transparent volumes, without load-bearing walls or monumental openings, which gave the buildings an appearance of spaciousness and incorporeality that would be the most attractive image of rationalism. Within a three-dimensional grid, the volumetric composition is based on translations and superimpositions of planes, with a fluid sequence of spaces that favors the multiplicity of functions.

A variant of Neo-Plasticism was Elementarism, a movement founded in 1924 by Theo van Doesburg. Faced with the primary colors and right angles promoted by De Stijl, Van Doesburg introduced greater dynamism through diagonals and rotations, described by this artist as "counter-compositions", which meant a break with Piet Mondrian. Although it began in painting, this style was also transferred to architecture, in which the constructivist and Bauhausian influence was denoted. Van Doesburg intended to make a synthesis between the arts and facilitate a practical application of artistic creation in everyday life. In 1924, Van Doesburg and Cornelis van Eesteren published Towards a Collective Construction, in which they declared that "painting, without architectural construction, has no raison d'etre." They developed their aesthetics in the Elementarism Manifesto (1926), in which they defended the contrasting of the diagonal in paintings and sculptures with the vertical-horizontal linearity of architecture, as they put into practice in the decoration of the Café L'Aubette in Strasbourg (1928-1929), made by Van Doesburg in collaboration with Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp.

Constructivism

Constructivism (1914-1930) was a movement that emerged in revolutionary Russia, a politically committed style that sought through art to transform society by reflecting on pure artistic forms conceived from aspects such as space and time, which generated in plastic arts a series of works of abstract style, with a tendency to geometrization. In its architectural aspect, it initiated a program linked to the revolution that sought a functional architecture that would satisfy the real needs of the population. Constructivism coincided with neoplasticism in the search for an art of collective utility based on objective aesthetic principles. The end of the movement came in 1932 with the suppression of artistic groups carried out by the Stalinist dictatorship.

Halfway between architecture and sculpture is the Monument to the Third International by Vladimir Tatlin (1919-1920), of which he only made the model. It would have consisted of a 395-meter-tall structure, with a stepped spiral shape that symbolized the progress of socialism, with floors that would rotate at different time intervals: daily, monthly, and yearly. According to Tatlin, the monument represented the "union of purely artistic forms (painting, sculpture and architecture) for a utilitarian purpose".

Like this one, many other projects of the time were not carried out due to the precariousness of the country's political situation, such as the largely utopian postulates of El Lissitzky, which brought together some of the premises of constructivism, neoplasticism and the Bauhaus. Among them are his Proun spaces, which anticipated the environments of later installation art, or his «cloudstriban» buildings (1925), horizontal skyscrapers supported by large tower-shaped pillars.

The most practical achievements were carried out by two associations: ASNOVA (Association of New Architects), created in 1923 under the premise of finding universal solutions for architecture, detached from form-function or form-social context relationships, and fundamentally represented by Konstantin Mélnikov, author of the Moscow Workers' Club (1925-1927) and of the Russian pavilion at the 1925 Paris Exhibition of Decorative Arts, and by Nikolai Ladovsky, author of the Lenin Institute in Moscow (1927); and the OSA (Union of Contemporary Architects), founded in 1925 with the aim of uniting artistic and political avant-garde and creating a productive and utilitarian art, represented by the brothers Aleksandr, Leonid and Víktor Vesnín (Moscow Palace of Labor, Pravda in Leningrad, Lenin Institute in Moscow) and by Iván Nikolayev. It is also worth noting in the promotion of Russian constructivism the work of Vjutemás (acronym for Higher Education Workshops of Art and Technology), a state art and technical school located in Moscow that fostered the avant-garde in art and architecture.

In the field of urbanism, the essential concern was housing, which resulted in the «communal house» projects, such as those developed by Moiséi Guínzburg (Narkomfin Collective House in Moscow, 1929). In 1929, the ARU (Union of Urban Planners Architects) was founded, within which two urban tendencies developed: that of the "urban planners", advocates of restructuring traditional cities; and that of the "desurbanistas", who promoted the creation of longitudinal settlements inspired by Arturo Soria's Ciudad Lineal.

Organism: Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright was an American architect, pioneer of organic architecture and founder of the Prairie School movement. In his work, certain coincidences with rationalism can be perceived, such as the use of terraces and perpendicular forms, but from an organic approach, that is, adapted to nature: the architectural forms merge with the natural ones in an integrated and harmonious whole, as in his famous Kaufmann house, better known as House of the waterfall (in English Fallingwater, 1936-1939).

Wright initially worked in the studio of Louis Sullivan for six years and inherited from his teacher the idea that American architecture should be renewed. Even so, he thought that the basis of this renewal was in the traditional North American way of life and in the integration of man with nature achieved by the pioneers of the American West. Thus, Wright's constructive ideal was the single-family house with horizontal spaces, wide ceilings and a perfect interrelationship with the environment, as in the Cascade House, which forms part of the surrounding landscape. He thus created the typology of prairie houses (houses on the prairie), of which he built quite a few for businessmen and magnates, as well as his own residence, Taliesin West, in Scottsdale, Arizona (1938).

For Wright, architecture should encompass both the construction itself and its adaptation to its environment; according to his words: "an architecture that develops from the inside out, in harmony with the conditions of its being", as well as that "in organic architecture, then, the building as one thing, its furniture as another, and its position and its environment as another one". Wright adopted from the English movement Arts & Crafts the idea of “total design”, for which reason in his works he designed both the exterior and the interior of the houses, with a type of furniture that was equally organically conceived. Other prominent Prairie School architects included William Gray Purcell and George Grant Elmslie.

Rationalism

The Bauhaus

The Bauhaus School is usually considered the first exponent of a fully mature rationalism. The Staatliche Bauhaus (State Building House) was born in 1919, when the architect Walter Gropius took over the direction of the Weimar School of Arts and Crafts, which he reoriented towards a multidisciplinary study program that attended both architecture and design and decorative arts: students at the school learned theories of form and design, as well as stone, wood, metal, clay, glass, weaving and painting workshops. The Bauhaus moved to Dessau in 1925 and to Berlin in 1932. Gropius was succeeded by Hannes Meyer in 1928 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1930. The school was closed by the center's management in 1933 due to harassment system to which they were subjected by the Nazi authorities.

The Bauhaus teaching program was based on the correlation between all creative processes, with the aim of unifying art and design. According to Gropius, "the ultimate goal of the Bauhaus is the collective work of art, in which there are no barriers between the structural arts and the decorative arts." Thus, architects, artists and craftsmen would work together in the construction of the "building of the future". At first, the Bauhaus was influenced by the Viennese Sezession and the Wiener Werkstätte, as well as by William Morris and the Arts movement. & Crafts, by Peter Behrens and Henry Van de Velde, as well as the expressionism that was fashionable in Germany at the time. However, from 1922 the influence of the Dutch De Stijl group was noted and the school became more austere and functionalist, and more oriented towards industrial design. Again according to Gropius, "we want an architecture adapted to our world of machines, radios, and fast-engined cars, an architecture whose function is clearly identifiable by the relationship of its forms."

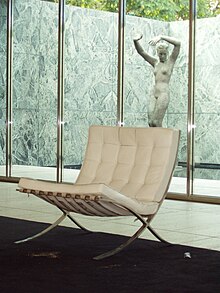

Four phases can be distinguished in the history of this school: the first (1919-1924) corresponds to his stay in Weimar and the architectural formulations that are proposed are still of survival of the expressionist style, with a certain utopian component; With hardly any material achievements, the most relevant project sketched at this stage is Gropius's project for the headquarters of the Chicago Tribune (1922, not carried out), as well as that of an International Philosophical Center in Erlangen (1923-1924), also not carried out. The second stage (1925-1930) began with the move to Dessau, where the school's headquarters building was built, the work of Gropius. The line of the school is already fully rationalist, with a clear commitment to design and industrial production. The main architectural characteristics of these years are the geometric planimetry, the orthogonal layout, the use of glass curtain walls and horizontal windows, as can be seen in the projects of "large-scale construction houses" (1924), the houses of teachers (1925-1926) or the Törten Colony in Dessau (1926). During the direction of Hannes Meyer (1928-1930) there was a greater link with the political left and an architecture at the service of the needs of the population was opted for, more practical and far from pure forms, which denotes the influence of constructivism Russian. Meyer's main works were the project for the Palace of the League of Nations in Geneva (1926-1927) and the School of Trade Unions in Berlin (1928-1930). After Mies van der Rohe (1930-1933) took over the leadership, the school moved towards a conception of architecture more focused on structural issues, with some influence from the Dutch group De Stijl and the Russian architect and artist El Lissitzky. Among Mies's works in these years, the following stand out: the German Pavilion for the Barcelona International Exposition (1929), the Tugendhat house in Brno (1930) and the Lemcke house in Berlin (1932).

In 1923, the Bauhaus organized an exhibition entitled Art and Technology: A New Unity, which featured Georg Muche's Experimental House or Haus am Horn and Adolf Meyer, a prototype of a mass-produced functional house built in steel and concrete, completely decorated with objects and furniture designed by Marcel Breuer. In 1927 the department of architecture was established, until then non-existent despite the multidisciplinary approach of the school., headed by Hannes Meyer and, in 1928, an urban planning department, headed by Ludwig Hilberseimer.

Probably the most outstanding architectural achievement of this school is the Bauhaus building in Dessau, designed by Gropius in 1925. He created it with strict criteria of functionality, which is why it became an icon of rationalist architecture. The building consisted of two bodies, one rectangular with classrooms and laboratories and the other L-shaped with an auditorium, stage, kitchen and dining room, five stories high that housed rooms for students, bathrooms and a gym. Both buildings were connected by a two-story high bridge, which housed the administration offices. He mainly used concrete and glass as materials, with profuse use of curtain walls.

France

As seen in the background, the pioneers of a pre-rationalism in France were Tony Garnier and Auguste Perret. The general lines of later French rationalism were based on most of the premises of the International Style, although with less interest in functionality than in German rationalism. In 1929 the Union des Artistes Modernes (UAM) was founded, where in addition to painters and sculptors involved architects such as Robert Mallet-Stevens, Charlotte Perriand, René Herbst, Pierre Chareau and Pierre Barbe; in 1931 Le Corbusier, Gropius, Victor Bourgeois and Willem Marinus Dudok joined; in 1932, André Lurçat and Alberto Sartoris. This association promoted various exhibitions and, in 1934, published the manifesto Pour l'art moderne, cadre de la vie contemporaine, which defended modern architecture. On the other hand, in 1930 the magazine Architecture d'aujourd'hui was founded, directed by André Bloc, which served as an organ for the dissemination of the new architecture.

Le Corbusier

The main referent of French rationalist architecture was Le Corbusier, the pseudonym of Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris. Although Swiss by birth, he settled in Paris in 1917 (at the age of thirty) and became a French national in 1930. He was an engraver, designer, painter, sculptor and writer, although, paradoxically, the person who most influenced architecture in the XX did not qualify as an architect. He was influenced early by Tony Garnier and Auguste Perret, as evidenced by his use of the reinforced concrete. Le Corbusier represents a classicist rationalism, which has its roots in Greco-Roman architecture; as he affirmed, his only teacher had been history. For him, «architecture is the wise, correct and magnificent game of volumes assembled under light. Cubes, cones, spheres, cylinders or pyramids are the great primary shapes that light reveals well. It is the essential condition of the plastic arts”.

Among his first formulations is the Maison Domino (1914), a typical house conceived as an elementary housing cell to be mass-produced and that would allow the layout of free plans, formed by a concrete structure supported on six cantilever beam uprights. A more evolved variant would be the Maison Citrohan (1920), a habitable unit designed —in his words— “like a bus or the cabin of a ship », and that would serve as a minimum cell to build blocks of flats that he would call immeuble-villas («city-buildings»), as he materialized in his villa Besnus de Vaucresson in 1922.

In the beginning he was linked to purism, a variant of synthetic cubism led together with Jeanneret by Amédée Ozenfant. They admired the beauty and purity of machines, which was their main inspiration along with mathematics, with a desire to integrate architecture, painting and design, concepts that they developed in the magazine L'Esprit Nouveau (1920-1925) and in the book Vers une architecture (1923), as well as in the L'Esprit Nouveau pavilion for the Decorative Arts Exhibition of Paris in 1925. In 1922 he teamed up with his cousin, the engineer Pierre Jeanneret, with whom he opened a studio in Paris and, from 1927, he collaborated with Charlotte Perriand on furniture design.

Just as Mies van der Rohe preferred steel and glass and Le Corbusier used reinforced concrete, both nevertheless achieved free and open structural solutions, which would be the main stylistic hallmark of their work. Another of its characteristics would be the use of pilotis, some concrete pillars that allowed the building to be supported on an empty space, which accentuated the sensation of volume as opposed to that of mass. In 1926 he published his Five points for a new architecture, in which he recounted his main architectural proposals: the ground floor on pilotis, the free plan, the free façade, the longitudinal window (fenêtre en longueur) and the terrace-garden., which he first developed in the villas Jeanneret and La Roche in Paris (1923). He applied all these principles in the villa Stein in Garches (1927) and, especially, in the villa Savoye in Poissy (1928-1930), one one of the most accomplished examples of rationalist architecture, made up of a square-shaped floor raised from the ground by a se rie de pilotis, with an open floor plan, elongated horizontal windows and a flat roof on which there is a terrace-garden; it has no façade, no front or back, but is an unfathomable whole from a single point of view. In 1927 he built a version of his Maison Citrohan for the Weißenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart, for which he also built another double-dwelling building. In these years he also drew up the unrealized projects for the Palace of the League of Nations in Geneva (1927), the World Museum for the Mundaneum in Geneva (1929) and the Palace of the Soviets in Moscow (1931). Between 1929 and In 1933 he built the Cité de Refuge in Paris for the Salvation Army, a building inspired by nautical design and, between 1931 and 1933, the Swiss Pavilion for the International University City of Paris.