Quipu

The quipu (the name is derived from the Quechua word khipu, which means knot, tie, lacing) was an information storage instrument consisting of woolen ropes or cotton of different colors, provided with knots, used by Andean civilizations. Although it is known that it was used as a system of accounting and storage of epic tales of the deceased Incas, certain authors have proposed that it could also have been used as a graphic writing system, a hypothesis supported among others by the engineer William Burns Glynn. These instruments were in the possession of quipucamayoc specialists (khipu kamayuq), administrators of the Inca Empire, who were the only ones qualified to decipher these enigmatic tools and authorized to state their content.

Quipus have been found from the Huaca of the University of San Marcos, to the Cerro del Oro, corresponding to the Wari culture. Currently, around 750 quipus are preserved in museums, most of them from the colonial era.

The quipus were known by the chroniclers, who spoke carefully about them and used the information they contained, interpreted and provided by the khipu kamayuqkuna, specialized in their management. According to José de Acosta (1590):

There are quipus memorials or logs made of branches, in which various knots and different colors mean different things. It is amazing what they achieved in this way, because how much books can tell of stories, and laws, and ceremonies and business accounts, all that add up the quipus so punctually, they admire.

The use of quipus continued during the Viceroyalty of Peru after the conquest of the Inca Empire, declining in use due to literacy and the deterioration of traditional Inca institutions.

Structure

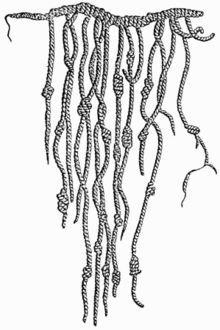

The quipu consists of a main rope, without knots, from which other generally knotted ropes depend and of different colors, shapes and sizes, the colors are identified as sectors and the knots the quantity —called hanging ropes. There may be ropes without knots, as well as ropes that do not come off the main one but rather the secondary ones (secondary ropes). Contemporary specialists think that the colors and perhaps the braiding of the ropes indicate the objects, while the knots would refer to quantities, including the number zero. Among the known quipus there is a great variety of size and complexity, ranging from the very simple to those with more than a thousand strings.

Marcia and Robert Ascher of the University of Michigan analyzed several hundred quipus, finding that most of their information is numerical. Each group of knots is one digit, and there are three main types of knots:

- Simple, knot of a return (represented by s in the Ascher system;

- Longconsisting of a knot with one or more extra laps (represented by a L in the Ascher system;

- In the form of 8(represented by E in the Ascher system).

In Ascher's system a fourth type of knot, in the shape of an eight with an extra turn, is represented by EE. A number is represented by a sequence of groups of nodes in decimal base.

- The powers of ten are shown a position along the chain and that position is aligned between the successive chapters.

- The digits in the decimal positions and for the higher powers are represented by simple knot groups (for example, 40 is four simple knots in a row in the ten position).

- The digits in the unit positions are represented by long knots (e.g. 4 is a knot with 4 turns). Because of the way the knots are tied, digit 1 cannot be shown this way and is represented in that position by an eight-shaped figure.

- The zero is represented by the absence of a knot in the appropriate position. (represented by one X in the Ascher system)

- Because the digit of the units is shown in a distinctive form, it is clear where a number ends. A chapter in a quipu therefore can contain several numbers.

Examples in the Ascher system:

- Number 731 would be represented by 7s, 3s, E;

- Number 804 would be represented by 8s, X, 4L;

- Number 107 followed by number 51 would be represented by 1s, X, 7L, 5s, E.

This reading can be confirmed by a fortunate fact: quipus regularly contain sums in a systematic way. For example, a string can contain the sum of the following strings and this relationship is repeated throughout the quipu. Sometimes there are sums of sums too.

Some of the data is not numbers, but what the Aschers call number labels. They are made up of digits, but the resulting number appears to be used as a code, such as the ones we use to identify people, places, or things. With the context of the individual quipus unknown, it is difficult to guess what these codes mean. Other aspects of the quipu could have communicated information as well, for example: color coding, relative placement of strings, spacing and structure of strings and secondary strings.

Colors

| Colors: | Sector |

|---|---|

| Pardo: | Government |

| Carmesi: | Inca |

| Morado: | Curaca |

| Green: | Conquest |

| Red: | Guerrero |

| Black: | Time |

| Yellow: | Gold |

| White: | Silver |

| Celeste: | Respect |

| Blue: | Water |

Types of rope

Different types of rope were used, each one had at least two strands:

- PrimaryThe thickest, from which all the others come directly or indirectly.

- Pendant stringsThe ones hanging from the main down.

- Senior positionsThe ones that link to the main, directed upward. One of its utilities was to group hanging strings. Another, often used, was to represent the sum of the numbers expressed in the hanging strings.

- Final pendantIts end in the form of a loop is attached and tight to the end of the main rope. This rope doesn't appear in all the quipus.

- Secondary or auxiliary curvesJoin another one that's linked to the main one. They could in turn unite another auxiliary rope. He tied himself to the middle of the rope he preceded.

Use

It is known of its accounting use, census and harvest records. and its usefulness as a system of linguistic representation and memory of history, songs and poems as well as for counting cattle is investigated. Ancient Inca recording and communication instrument, which consisted of a long rope, from which 48 secondary ropes hung and several others attached to the previous ones. The knots that were made in the ropes represented the units, the tens and the hundreds; and the lack of knots, the zero. A sample of quipu (VA 42527, Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin), previously studied by Gary Urton, shows an unusual quadrant division. Associating the Statistical Data Analysis with the experimental investigation of said sample, in a study published by Alberto Sáez - Rodríguez the coordinates corresponding to a 2-dimensional star map were obtained, which indicates the exact position of the brightest stars in the cluster of the Pleiades. Knowing that at least 6 of the cluster stars are visible to the naked eye, point 7 could correspond to the coordinates of the planet Venus, which passes in front of the Pleiades every 8 years. This would prove that the Incas already knew how to handle rectangular (Cartesian) coordinates.

Accounting

Its use as a numbering system is the best known form. In this case, the secondary strings each represent a number. The knots indicate the figures according to their order: the units are at a greater distance from the main cord. Pablo Macera says that the quipu was the matrix element of the Inca culture and that political control was partly due to the fact that through them they could carry out an estimate of the towns they controlled. For counting, they also relied on the use of the yupana or Inca abacus, whose existence is known by chroniclers, but not its specific handling, although today it has been adapted as a pedagogical instrument, for teaching mathematics in intercultural projects in Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador and the Dominican Republic.

Possible writing

In the Andes, writing with characters on a surface was not known, as it is understood in the West, but the quipus seem to have been an effective mnemonic tool in the administrative tasks of the Inca civilization and that they could also have been used to remember events that happened.

Several authors have considered them an information coding system comparable to writing since it is possible to achieve more than 8 million combinations thanks to the diversity of rope colors, distance between ropes, positions and types of possible knots. It is not known how the textual content could have been encoded beyond some simple sequences. There are some remote Andean towns that mention having "writings" on the quipus of their locality.

According to the Jesuit José de Acosta in 1590, referring to the quipus, he wrote: "They are quipos, some memorials or records made of branches, in which different knots and different colors mean different things. It is incredible what they achieved in this way, because as much as books can say about stories, and laws, and ceremonies and business accounts, all of this is supplied by the teams so punctually that it admires"

William Burns Glynn states that the quipus were books with an alphanumeric writing where the numbers symbolized in each knot represent a consonant of the Quechua language and, in turn, have an equivalence with the colors of the ropes and with the geometric drawings used in textile borders and in pottery, with which they also become texts of Inca writing.

For Robert and Marcia Ascher, writing in quipus was based on cross-categorization arrangements, that is, organized sets of numerical data corresponding to categories, which could represent quantities of objects, serve as labels, or simply formalize information. According to Felipe Guamán Poma, the Kapakkuna or quipus with lists of rulers included in the same order a summary of their character traits, the name of the Colla (main wife), the years who ruled and his main actions.

On August 12, 2005, Science magazine included the report Khipu Accounting in Ancient Peru by anthropologist Gary Urton and mathematician Carrie J. Brenzine, according to which a non-numerical element in a quipu had been deciphered for the first time: a sequence of 3 knots in the shape of an 8 at the beginning of a quipu that could mean a place name for the town of Puruchuco.

Although 85% of the quipus that are available to experts show the pattern of the accounting quipus, 15% follow other arrangements and it is assumed that they can be used to decipher the writing codes. To look for an & #34;Rosetta quipu" In order to decipher it, the information from the chroniclers was used, according to which the Spaniards looked for quipucamayoc so that they could read quipus, while an interpreter translated into Spanish and a scribe copied the Inca accounts and memoirs. At least one example of this transcription had to be found. Gary Urton found a document that records the taxes paid by the inhabitants of a community in the Santa Valley.

The mathematician Manuel Medrano, then a student at Harvard, bought 6 quipus from the Santa Valley organized into 132 divisions from an Italian collector, which coincide with the 132 names that appear in the document found by Urton. The values of the knots in the first cords of the groups of six add up to the same as the tribute of the document and it is estimated on this basis that the qipus and the revision document correspond to the same administrative procedure. The fastening knots of the first ropes of the groups of six ropes vary in a binary way, that is to say tied in "verso" or "obverse". It is argued that this construction feature divides the censused tributaries into halves; therefore, these qipus correspond to the social organization of the community referred to in the document. It is suggested that the names of the tributaries could be listed with color codes on the qipus.

History

The oldest quipu found so far was found in 2005, among the remains of the city of Caral and dates from approximately 2500 BC. C., makes it evident that the use of the quipu has a great antiquity. It is also known that they were widely used by the Huari, eight hundred years before the Incas. The quipus huari did not have knots, but ropes of different colors hanging from the main one at different points.

They were used by the Inca Empire to record the population of each of the ethnic groups that provided their labor through the mita and the production stored in the colcas (qullqa) for which every deposit had its resident khipukamayuq.

In the "Reports" From Viceroy Martín Enríquez de Almansa, the use of the quipu as a code of the Inca Laws is documented. So the Inca judges "resorted to the help of posters that were available on the kippah and... others, that were available on various multi-colored boards, from which they understood what was the guilt of each criminal". The jurist Juan de Matienso wrote in 1567 that "the disputes that the indigenous people fought with the caciques or noble persons, civil and criminal, were registered in the qipu tukuiriku. According to Garcilaso de la vega

The Spanish destroyed painted tablets and quipus containing the laws and codes of Inca law, during the conquest of the Inca Empire and the city of Cuzco in particular."Messages were sent to determine whether the right justice had been done, so that the junior judges were not negligent in administering it, and if they did not administer it, they were severely punished... The way of transmitting such messages to the Inca and its [people] from its supreme council were knots tied with strings of different colors, so they explained, as in numbers, by knots of this and such color they spoke of crimes that were punished, and certain strings of different colors with which the thickest strings were intercepted spoke of the punishments that were carried out and the laws that were applied. And so they understood each other, because they had no lyrics. "

The chronicler Pedro Cieza de León, after locating the origin of the quipus in the narrators in charge of memorizing and recounting the events during the government of each Inca, points out that in each provincial capital there was a qipukamayuq in charge of all the accounts, including the relative ones According to the importance of the deposit, some of these accountants could have belonged to the lineage of the Inca.

The Spanish conquistadores did not quickly suppress the use of quipus. After the Spanish conquest, the use of quipus was initially encouraged, both by the colonial administration and by the church. Between 1570 and 1581, Viceroy Francisco de Toledo incorporated the quipu into the administrative system of the Viceroyalty, although he ordered written copies of what they contained to be made on paper. They were frequently used in Catholic worship to memorize prayers and to remember sins in confession. In 1583, the Third Limense Council prohibited its use to keep indigenous memories, rites and customs and ordered the Indians to remove the quipus that dealt with these issues, but at the same time ordered that the indigenous people write down their sins in quipus to be able to confess them. Despite the ban, the communities continued to use quipus. In 1602, the mayor of Xauxa ordered the burning of a quipu because it contained the history of the communities of the Mantaro valley. In 1622 the parish priest of Andahuaylillas, Juan Pérez Bocanegra, wrote a text on the confessional quipu in his Ritual form , which describes how the indigenous people went to confession with quipus that recorded their sins. Quipus were used for at least 150 years after the Conquest and carbon 14 tests have revealed that most surviving quipus date from colonial times.

Post-conquest quipu narratives were characterized by attenuated clauses and enumerated lists focused on chronology and tribute, which constituted a flattening of the expressive capacity of quipus after the Spanish conquest.

Currently, the meaning of the nearly 700 surviving quipus is still being investigated, including those found during the 20th century in tombs of all kinds, which serves to expand knowledge about ancient Peru.

Current location of the surviving quipus

According to the KHuipu Database Project led by Harvard University professor Gary Urton and his colleague Carrie Brezine, 751 quipus have been reported to exist today. They are found in Europe, North America, and South America. Most are in museums outside of their original countries, but some reside in Peru in the care of descendants of the Incas. The largest collection is in the Berlin Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin, Germany, with 298 quipus. The next largest collection in Europe is that of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Munich, also in Germany. In Peru there are 35 quipus in the Pachacamac Museum and another 35 in the National Museum of Archeology, Anthropology and History of Peru, both in Lima, the Mallqui Center in Leimebamba has 32 quipus. The Temple Radicati Museum in Lima has 26, the Ica Museum has 25, and the Puruchuco Museum in Ate has 23. The quipus found in private collections have not been counted in the database and their number is unknown. A prominent private collection is in Rapaz, Peru, and was recently investigated by University of Wisconsin-Madison professor Frank Salomon. The Department of Anthropology and Archeology of the University of California at Santa Barbara and the Museum of Andean Sanctuaries of Peru - Arequipa also have a quipu respectively.

The quipus of Tupicocha and Rapaz

Currently the communities of Rapaz, in the highlands of the Lima region - Peru, keep quipus that they use as a sign of authority within their communities. These quipus are stored in a house called "Kha Wayi" and are a fundamental piece for ancestral rites such as the "Caccahuay". The Tupicocha quipus were included by the National Institute of Culture of Peru within an ethnographic record called the Qhapaq Ñan Program.

Contenido relacionado

Lautaro Lodge

Kingdom of Navarre

Mayan codices

![Ejemplos de nudos de quipus.[6]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/91/Endacht.jpg/120px-Endacht.jpg)