Quiché Department

El Quiché is one of the twenty-two departments that make up Guatemala, it is located in the northwestern region of the Republic of Guatemala. Its capital is Santa Cruz del Quiché.

Shortly after the conquest of Guatemala, the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes region was part of the Tezulutlán region (Spanish: "war zone") where numerous indigenous people entrenched themselves to resist the Spanish conquest. When the Spaniards and indigenous Tlaxcaltecas and Cholultecas invaded Guatemala in the 1520s, the region of Sacapulas and other indigenous Ixil and Uspantek villages resisted the conquest for several years thanks to their location in the Cuchumatanes mountain range and the ferocity of their warriors; After several years of defeating Spanish conquest attempts, they were finally defeated in December 1530, and the surviving warriors were branded as slaves in punishment for their prolonged resistance.

The department itself was created from the original departments of Totonicapán/Huehuetenango and Sololá/Suchitepéquez that had been created in 1825, a few years after the Independence of Central America. The de facto provisional government of Miguel García Granados On August 12, 1872, he considered it appropriate to create the new department to achieve better administration of the region.

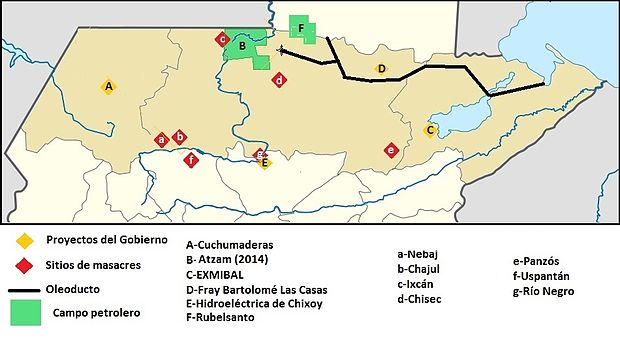

Since 1970 it belongs to the Northern Transversal Strip and during the civil war that the country experienced between 1960 and 1996 it was the scene of bloody combats and scorched earth policies, mainly in the oil area of Ixcán, especially after 1972, with the entry into the territory of the Guerrilla Army of the Poor. It borders Mexico to the north; to the south with the departments of Chimaltenango and Sololá; to the east with the departments of Alta Verapaz and Baja Verapaz; and to the west with the departments of Totonicapán and Huehuetenango.

History

Spanish conquest

In the ten years after the fall of Zaculeu, the Spanish tried to invade the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes to conquer the Chuj and Q'anjob'al peoples and to search for gold, silver and other riches; However, the remoteness and difficulty of the terrain made its conquest difficult.

After the Spanish conquered the western part of the Cuchumatanes mountain range, the Ixils and Uspantecos (uspantek) managed to evade them; These towns were allies and in 1529 the Uspantec warriors were harassing the Spanish forces trying to foment rebellion among the Quiché. Gaspar Arias, magistrate of Guatemala, entered the eastern Cuchumatanes with an infantry of sixty Spanish soldiers and three hundred indigenous allied warriors and by early September he had managed to temporarily impose Spanish authority in the area occupied by the modern towns of Chajul and Nebaj. Then, as he marched east toward Uspantán, Arias received notice that the acting governor of Guatemala, Francisco de Orduña, had removed him as magistrate and he had to return to Guatemala, leaving the inexperienced Pedro de Olmos in command. Olmos launched a disastrous frontal assault on the city, where the Spanish were ambushed from the rear by more than two thousand Uspantec warriors; The survivors who managed to escape returned, harassed, to the Spanish garrison in Q'umarkaj.

A year later, Francisco de Castellanos led a new military expedition against the Ixils and Uspantecos, with eight corporals, thirty-two mounted men, forty Spanish soldiers on foot and hundreds of indigenous allied warriors; On the highest slopes of the Cuchumatanes, in the area occupied by the modern municipality of Sacapulas, they faced almost five thousand Ixil warriors from Nebaj and nearby settlements. The Spanish forces besieged the city and their indigenous allies managed to scale the walls, penetrate the fortress and set it on fire; the survivors were marked as slaves to punish them for their resistance. The inhabitants of Chajul, upon learning this, immediately surrendered and The Spanish continued towards Uspantán where there were ten thousand warriors, coming from the area occupied by the modern municipalities of Cotzal, Cunén, Sacapulas and Verapaz; The deployment of the Spanish cavalry and the use of firearms decided the battle in favor of the Spanish who occupied Uspantán and again marked all the surviving warriors as slaves. The towns in the surrounding area also surrendered and in December 1530 the conquest of the Cuchumatanes ended. The Ixil people were then divided into four towns, thus forming Nebaj, Cotzal, Chajul, and Ilom.[citation required]

According to Brother Francisco Ximénez, O.P. (century XVII-XVIII< /span>), the word quiché or k'iche' means 'forest, jungle, many trees'. It is made up of the voices ki: 'how many'; che: 'trees', which also produced the Quiché word kechelau, which means 'forest'. Currently there are new studies of these roots, which literally are: k'i "many" (which is different from how many, according to Ximénez) and che' "tree".

The territory was inhabited by the great Quiche Kingdom, whose capital and main city, Gumarcaj (Utatlán), was located near the current departmental capital.

The indigenous chronicles indicate that when the population grew there was a need to settle new populations in the place called Chi-Quix-Ché.

Capitulations of Tezulutlán

In November 1536, the friar Bartolomé de las Casas, O.P. He settled in Santiago de Guatemala. Months later, Bishop Juan Garcés, who was a friend of his, invited him to move to Tlascala. Later, he moved again to Guatemala. On May 2, 1537, he obtained from the licensed governor Don Alfonso de Maldonado a written commitment ratified on July 6, 1539 by the Viceroy of Mexico Don Antonio de Mendoza, that the natives of Tuzulutlán, when they were conquered, would not be given in encomienda but who would be vassals of the Crown. Las Casas, along with other friars such as Pedro de Angulo and Rodrigo de Ladrada, sought out four Christian Indians and taught them Christian songs where basic issues of the Gospel were explained. Later he led a delegation that brought small gifts to the Indians (scissors, bells, combs, mirrors, glass bead necklaces...) and impressed the chief, who decided to convert to Christianity and be a preacher to his vassals. The chief was baptized with the name of Juan. The natives consented to the construction of a church but another chief named Cobán burned the church. Juan, with 60 men, accompanied by Las Casas and Pedro de Angulo, went to speak with the Indians of Cobán and convinced them of their good intentions.

Las Casas, Brother Luis de Cancer, Brother Rodrigo de Ladrada and Brother Pedro de Angulo, O.P. They took part in the reduction and pacification project, but it was Luis de Cancer who was received by the chief of Sacapulas and managed to perform the first baptisms of the inhabitants. The chief "Don Juan" took the initiative to marry one of his daughters to a principal from the town of Cobán under the Catholic religion.

Las Casas and Angulo founded the town of Rabinal, and Cobán was the head of Catholic doctrine. After two years of effort, the reduction system began to have relative success, as the indigenous people moved to more accessible lands and towns were founded in the Spanish style. The name "Land of War" was replaced by "Vera Paz" (true peace), a name that became official in 1547.

Colonial era

During the colonial period, Quiché was part of the provinces of Totonicapán or Huehuetenango and Sololá or Atitlán.

It has been theorized that the first version of the Popol Vuh was a work written around the year 1550 by an indigenous person who, after learning to write with Latin characters, captured and wrote down the oral recitation of a old man. But this hypothetical author "never reveals the source of his written work and instead invites the reader to believe what he wants from the first recto folio," which Friar Francisco Ximénez, O.P., used. to translate the book. If such a document existed, this version would have remained hidden until the period 1701-1703, when Ximénez became a doctrinal priest of Santo Tomás Chicicastenango (Chuilá).

Ximénez transcribed and translated the text in parallel columns of K'iche' and Spanish and later he made a prose version that occupies the first forty chapters of the first volume of his History of the province of Santo Vicente de Chiapa and Guatemala that he began writing in 1715. Ximénez's works remained archived in the Convent of Santo Domingo until 1830, when they were transferred to the School of Sciences of Guatemala after the expulsion of the Dominicans from the states of the Central American Federation. In 1854 they were found by the Austrian Karl Scherzer, who in 1857 published the first Ximénez carving in Vienna under the primitive title The stories of the origin of the Indians of this province of Guatemala. For his part, the Abbé Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg stole the original writing from the university, took it to Europe and translated it into French. In 1861 he published a volume under the title Popol Vuh, le livre sacré et les mythes de l'antiquité américaine. It was he, then, who coined the name Popol Vuh.

Later studies demonstrated that Father Ximénez did not faithfully translate the content of the K'iche' book and that he modified the text to facilitate his preaching task. However, other archaeological investigations have found evidence of the gods mentioned in the Popol Vuh in different Mayan cities and monuments.

Doctrines of the Dominicans

The Spanish crown focused on the catechization of the indigenous people; The congregations founded by royal missionaries in the New World were called "Indian doctrines" or simply "doctrines." Originally, the friars had only a temporary mission: to teach the Catholic faith to the indigenous people, later giving way to secular parishes. like those established in Spain; To this end, the friars must have taught the gospels and the Spanish language to the natives. When the indigenous people were catechized and spoke Spanish, they could begin to live in parishes and contribute with the tithe, as the peninsulars did.

But this plan was never carried out, mainly because the crown lost control of the regular orders as soon as their members embarked for America. On the other hand, protected by their apostolic privileges to help the conversion of the indigenous people, the missionaries only attended to the authority of their priors and provincials, and not to that of the Spanish authorities or those of the bishops. The provincials of the orders, in turn, were only accountable to the leaders of their order and not to the crown; Once they had established a doctrine, they protected their interests in it, even against the interests of the king and in this way the doctrines became Indian towns that remained established for the entire rest of the colony.

The doctrines were founded at the discretion of the friars, as they had complete freedom to establish communities to catechize the indigenous people, with the hope that these would eventually pass under the jurisdiction of a secular parish that would be paid the tithe; In reality, what happened was that the doctrines grew without control and never came under the control of parishes; They were formed around a capital where the friars had their permanent monastery and from said capital they went out to catechize or visit the villages and hamlets that belonged to the doctrine, and which were known as annexes, visitations or visiting towns.

The collective administration by the group of friars was the most important characteristic of the doctrines since it guaranteed the continuation of the community system in the event of the death of one of the leaders.

In 1638, the Dominicans separated their great doctrines - which represented considerable economic income - into groups centered on their six convents: The convents were in: the city of Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala, Amatitlán, Verapaz, Sonsonate, San Salvador and Sacapulas. Specifically in Sacapulas, the doctrine covered the towns of Sacapulas, Cunén, Nebaj, Santa Cruz del Quiché, San Andrés Sajcabajá, Zacualpa and Chichicastenango.

In 1754, by virtue of a Royal Decree part of the Bourbon Reforms, all the curates of the regular orders were transferred to the secular clergy.

In 1765, the Bourbon reforms of the Spanish Crown were published, which sought to recover royal power over the colonies and increase tax collection. With these reforms, tobacconists were created to control the production of intoxicating beverages, tobacco, gunpowder, cards and the cockpit. The royal estate auctioned the tobacco shop annually and a private individual bought it, thus becoming the owner of the monopoly on a certain product. That same year, four subdelegations of the Royal Treasury were created in San Salvador, Ciudad Real, Comayagua and León and the political-administrative structure of the Captaincy General of Guatemala changed to fifteen provinces:

In addition to this administrative redistribution, the Spanish crown established a policy aimed at reducing the power of the Catholic Church, which until that moment was practically absolute over the Spanish vassals. This policy of diminishing the power of the church was based on the Enlightenment

After the independence of Central America

Article 2 of Decree 63 of the Constituent Assembly of the State of Guatemala, promulgated on October 27, 1825, granted the title and name of town to the capital.

Creation of the department

The area that includes the modern department of Quiché was distributed until 1872 between the departments of Sololá/Suchitepéquez and Totonicapán/Huehuetenango; After the Liberal Reform of 1871, the provisional de facto president Miguel García Granados decided to create the department of Quiché to improve the territorial administration of the Republic; The text of the decree is the following:

Government of Manuel Estrada Cabrera

During the government of Mr. Manuel Estrada Cabrera, the political and military head of the department was General Fidel Echeverría Flores.

By government agreement of November 26, 1924, Santa Cruz del Quiché was elevated to the category of city.

Northern Transversal Strip

After the overthrow of President Jacobo Árbenz in 1954, the Economic Planning Council (CNPE) was created, which began to use free market strategies, advised by the World Bank and the International Cooperation Administration (ICA) of the government of the United States. The CNPE and the ICA created the General Directorate of Agrarian Affairs (DGAA) which was in charge of dismantling the effects of Decree 900 of the government of Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. The DGAA was in charge of the geographical area that It bordered the departmental limit of Petén and the borders of Belize, Honduras and Mexico, and which over time would be called the Northern Transversal Strip (FTN).

The first colonizing project in the FTN was that of Sebol-Chinajá, in Alta Verapaz. Sebol, at that time, was considered a strategic point and a waterway through the Cancuén River, which connected with Petén to the Usumacinta River on the border with Mexico and the only road that existed was the dirt road built by President Lázaro Chacón. in 1928. In 1958, during the government of General Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) financed infrastructure projects in Sebol. In 1960, the then captain of the Guatemalan Army Fernando Romeo Lucas García inherited the Saquixquib farms. and Punta de Boloncó northeast of Sebol, Alta Verapaz, with an area of 15 caballerías each. In 1963 he bought the "San Fernando" El Palmar de Sejux farm with an area of 8 caballerías, and finally bought the "Sepur" farm, near "San Fernando", with an area of 18 caballerías. During these years he was a deputy in the Guatemalan Congress and lobbied to promote investment in that area of the country.

In those years, the importance of the region was in livestock farming, the exploitation of precious wood for export and archaeological wealth. Timber contracts were given to transnational companies, such as the Murphy Pacific Corporation of California, which invested 30 million dollars for the colonization of southern Petén and Alta Verapaz, and formed Compañía Impulsadora del Norte, S.A. The colonization of the area was done through a process by which land in inhospitable areas of the FTN was granted to farmers.

In 1962, the DGAA became the National Institute of Agrarian Transformation (INTA), by decree 1551 that created the Agrarian Transformation law. In 1964, INTA defined the geography of the FTN as the northern part of the departments of Huehuetenango, Quiché, Alta Verapaz and Izabal and that same year priests of the Maryknoll order and the Order of the Sacred Heart began the first colonization process, together with INTA, taking residents of Huehuetenango to the Ixcán sector in Quiché.

"The establishment of agrarian development zones in the area covered is declared of public interest and national urgency, within the municipalities: Santa Ana Huista, San Antonio Huista, Nentón, Jacaltenango, San Mateo Ixcatán, and Santa Cruz Barillas in Huehuetenango; Chajul and San Miguel Uspantán in Quiché; Cobán, Chisecón, San Pedro Carchá, Lanquínapa » —Decree 60-70, article 1.o |

The Northern Transversal Strip was officially created during the government of General Carlos Arana Osorio in 1970, through Decree 60-70 in the Congress of the Republic, for the establishment of agrarian development. High Guatemalan officials — including the president Fernando Romeo Lucas García and former president Kjell Eugenio Laugerud García—then became large landowners and investors taking advantage of the policies of relocating peasants, access to privileged information, expansion of public credit and large development projects; In fact, the Guatemalan officers formed the Army Bank, and diversified their pension funds.

Since 1974, crude oil had been exploited commercially in the vicinity of the FTN following the discoveries made by the oil companies Basic Resources and Shenandoah Oil, which operated jointly in the Rubelsanto oil field, Alta Verapaz. In 1976, when Laugerud García came to visit the Mayalán cooperative in the Ixcán sector, Quiché, which had been formed just ten 12 years before, he said: "Mayalán is located at the top of the gold," suggesting that the Transversal Strip del Norte would no longer be dedicated to agriculture or the cooperative movement, but would be used for strategic objectives of exploitation of natural resources. After that presidential visit, both oil companies carried out explorations in Xalbal lands, very close to Mayalán in Ixcán, where they drilled the "San Lucas" well with unsuccessful results. These explorations, which paved the way for future oil experiments in Ixcán, and the rest of the FTN, were also the main reason for the construction of the dirt road that runs through the Strip. Shenandoah Oil, the National Institute of Agrarian Transformation (INTA) and the Army Engineer Battalion coordinated to build that corridor between 1975 and 1979, which ultimately allowed powerful politicians, military personnel and businessmen of the time to take over many of the areas. of the lands where the timber wealth and oil potential lay.

The presence of the Guerrilla Army of the Poor in Quiché, especially in the oil region of Ixcán, caused the civil war to intensify in the area and the projects were not carried out. The region was partially abandoned until 2008, when construction of the highway along the strip began.

After the overthrow of Lucas García on March 23, 1982, a military triumvirate led by General Efraín Ríos Montt came to power, along with colonels Horacio Maldonado Shaad and Francisco Gordillo. On June 2, 1982, international journalists conducted an interview with Ríos Montt, who said the following regarding the government of Lucas García and the Northern Transversal Strip:

|

Guatemalan Civil War

In Nebaj the Guerrilla Army of the Poor acted, which justified the attacks on the infrastructure it committed by arguing that, on the one hand, they affected the economic interests of the State and the productive sectors, and on the other, that they violated the Army: «Destroy infrastructure with the concept of saying we are going to destroy the country's infrastructure, to damage the country, not that. I always had an explanation... in relation to the war we were experiencing and in relation to the tactical moment that why were we going to blow up this bridge, yes we were going to blow it up so that the Army would not pass through and so that it would not continue with its barbarity... to cut off their advance and retreat... But what is from Nentón to the north, the road was closed [end 81 start 82], the Army did not enter, no authority entered, the telegraphy poles that were in place were cut. "They were the means of communication that existed apart from the road." "By cutting off the power that reached the (Army) barracks, the power of the entire population was cut off, creating discontent among the people. Later, these sabotages became generalized to cause a total lack of control throughout the country and prepare conditions to move into an almost pre-insurrection period.

| Date | Responsible | Objective | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 July 1981 | EGP | Chichicastenango Municipality, Quiché | They partially burned the facilities through an arson bomb; then prevented the entry of the relief elements. |

| 13 November 1981 | EGP | Municipality of Zacualpa, Quiché | Destruction of the municipal headquarters. |

| 16 November 1981 | EGP | Electrical installations of INDE in Santa Cruz del Quiché | He left all the surrounding municipalities without electricity. |

| 16 December 1981 | EGP | Municipalities, post offices and police station in Tecpán, Chimaltenango | Destroying the facilities and killing of six people; they also painted in the town and sabotaged the inter-American road. |

| 18 December 1981 | EGP | The Treasure Bridge in Quiché | Total destruction of the bridge, cutting access to the Army. |

| 21 December 1981 | EGP | Municipality and post offices and telegraphs of Cunén, Quiché | They burned civil registration documents and then municipal facilities. |

| 19 January 1982 | EGP | Facilities of the National Electronics Institute (INDE) in Villa Nueva and Escuintla | Electrical supply was interrupted in twenty-two departments of the Republic. |

| 19 January 1982 | EGP | INDE Electric Power Plant in Santa Cruz del Quiché | A bomb destroyed the power plant, leaving all the surrounding municipalities without supply. |

| 27 January 1982 | EGP | Bridges that communicate the towns of San Miguel Uspantán, Nebaj and Chajul in Quiché | Total destruction of the two bridges, cutting access to the Army. |

To counteract the rise of the guerrilla offensive after the triumph of the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua in 1979, the government of Lucas García began the Scorched Land offensive in the region where the Guerrilla Army of the Poor operated, in the area from Chajul, Nebaj and Ixcán in Quiché, an oil-rich region of the Northern Transversal Belt; As part of this offensive, there were intense attacks on civilian populations that resulted in massacres that were recorded by the REHMI report and the reports of the Commission for Historical Clarification. For the description of massacre, the REHMI report defined collective murders associated with community destruction; The majority of the massacres recorded by the REHMI report correspond to the Department of Quiché; They are followed by Alta Verapaz (63), Huehuetenango (42), Baja Verapaz (16), Petén (10) and Chimaltenango (9), but they also appear in other departments. Data on the forces responsible reveal the importance of massacres as part of counterinsurgency policy. After October 1981 there are more testimonies of massacres and they are characterized by a more indiscriminate pattern, which suggests that after that date the massacres were more important, were planned with greater premeditation and carried out a more global destruction of the communities, in congruence with the great offensive developed by the Army from Chimaltenango towards large areas of the Altiplano. One in six massacres took place on an important day for the community; Whether on a market day, a holiday, or religious meetings, the attacks on designated days tried to take advantage of the population concentration to carry out their actions in a more massive way and in some cases they had a clear symbolic meaning. This aspect, together with the concentration of the population, and the control of the situation shown by the Army, shows that the attacks were planned.

Along with the burning and destruction of houses, torture, mass atrocities and the capture of the population appeared in more than half of the attacks. Burials in mass graves, often dug by the victims themselves, are also described in an important part of the testimonies; These clandestine burials in mass graves were often used as a way to hide evidence of the murders. On other occasions the massacres occurred within the framework of large-scale operations with a large deployment of military forces and support from aviation that bombed those areas. At least one in nine communities analyzed suffered bombings associated with massacres, either in the days before or after the bombing. After the attack, people most often fled (40%) as a way to defend their lives, whether to the mountains, into exile, or to another community; one in six villages that suffered massacres was completely devastated.

Burning of the Spanish embassy in Guatemala City

In January 1980, a group of peasants - among whom was Vicente Menchú - traveled to Guatemala City to present through legal channels a list of petitions against the abuses and murders that the Guatemalan Army was committing. in Quiché.

Documentary film Not one alive.

|

On January 31, 1980, the group of farmers arrived at the Central Campus of the University of San Carlos of Guatemala, where students from the same university advised them to make their precarious situation public. When the country's newspapers did not dare to publish their demands for fear of serious reprisals, and after all legal avenues to be heard were exhausted, the group decided to take over the facilities of the Spanish Embassy and use said takeover as a parade. of their demands taking advantage of the diplomatic inviolability of the premises. The reaction of the government of General Fernando Romeo Lucas García was energetic: the police surrounded the embassy facilities and after several hours of siege, the situation ended with the fire of the room in which all the people inside had taken refuge. of the embassy, including all its staff and prestigious Guatemalan legal professionals, who were in a meeting with the ambassador that day to arrange a law conference. After the event, the only two survivors were ambassador Máximo Cajal López and Gregorio Iujá Yoná, who was saved because he was under everyone who was inside the room, although at midnight he was kidnapped from the hospital and tortured to death..

Operation Sofia

From July 8 to August 20, 1982, already during the head of state of General Efraín Ríos Montt, the Guatemalan army implemented the Operation Sofia plan. The military intelligence report indicated that after the strong offensive launched against the insurgency In the last quarter of 1981, the guerrillas had been defeated and had not achieved their objective of reaching power in March 1982; But, in January 1982 the guerrilla had begun a political-military offensive to overcome the crisis that the Army offensive had represented. The intelligence report also states that the guerrilla offensive had increased in the region of Nebaj, in El Quiché due to the international aid that the insurgents had received from abroad and that two new fronts had been formed, the Fronterizo and the Afghanistan, which had approximately 30 combatants each, and were conveniently equipped with weapons and first aid equipment. As for the civilians who lived in the area, the intelligence report indicates that all the inhabitants of the region had been made aware by the guerrilla, they were hiding from the army in caves far from their towns and did not provide the information required of them..

The "Operation Sofia" plan document includes telegrams from the Army Broadcasting Service, which mentions that civilians were evacuated from the area, and requests that those captured be returned to their normal lives:

- 22 July: "Today, 1100 hours, Salquil 87-12, eighteen elderly people, twelve children, requested support for that superiority effect control subsistence and reinstatement to their normal life."

- July 24: "1500 hours were evacuated from conflictive area ten families were threatened by subversion, including five men, ten women, seventeen girls, fifteen children, one newborn. Families are pending for evacuation."

- July 25: "Increase number of evacuated eight men, thirteen women, seventeen children, a newborn."

- July 26: "Number of evacuees has been twenty men, twenty-seven women, six boys, twenty-five girls, a newborn."

Also, in the document there are examples of pamphlets from the army and the guerrilla, which were part of the psychological war that was being carried out and for which the Guatemalan army requested the General Staff for a small radio transmitter and the implementation of a psychological operations team, since the vast majority of the local population was very convinced of the guerrilla doctrine, was illiterate, and knew very little Spanish:

- Example of military pamphlet:

"People of Nebaj, it is time to meditate, it is time to think, to order our thinking, the experience of the past has to guide us to the future of Nebaj; we must think of our people, here our children live and this is also where our grandparents, our ancestors rest. The army does not repress and kill as they have made us believe, we must not be afraid of them. Let's get close to them and we'll see that they're not the way they've made us believe those bad men who are in the hidden mountain. No one comes to buy our fabrics for fear of the way, it is the subversives who have brought us this suffering, before we were happy with how little we had, now we have nothing and if we continue this way we will not get grains, or vegetables, we have to help the army to end these subversive people who are called guerrillas. We must help the army with the truth, the army is full of people like us, mostly peasants who sacrifice for our homeland, for the freedom of Guatemala. People of Nebaj, subversives do not believe in God; you do believe in God, we must fix our churches that are the stronghold of our Christian faith." "The Ixil brothers who help these gangs of scavengers are deceived by false promises, let us help our brothers get them out of these organizations that will only bring death to them and their families. We must bear in mind that these subversive people will never succeed, for we are convinced that this struggle will only bring us death and poverty. The army is better trained and trained, but with that of God and we will end these bandits. Trusted people, organize it to save Nebaj. It is not possible for a few bandits to symbolize terror and mistrust; only organized will we defend Nebaj, we are already tired of so much violence. Violence they brought to us themselves that they call themselves guerrillas. It's time to pay them with their own medicine. Help the army that in this way will help your people. |

- Example of guerrilla pamphlet:

"Self-defense is all those measures that the organized population has to put into practice to defend itself from the enemy, to suffer the least number of casualties and damage when it attacks, to prevent its economy (seasons, crops, trade, etc.) from suffering great losses, so that its revolutionary and combative morals do not break, in order to beat the enemy even if it is launched attacking the population. In the last offensive that the enemy launched on our front in the months of January, February, March of the present year it was seen that the populations that did not put into practice the measures of Self-Defense in a correct and revolutionary way suffered a lot of loss of life: men, women, elders, children, hasa pregnant women, many of them were burned inside their ranches, fired with machetes, tortured them and many women raped them. These painful losses were largely due to the fact that these companions did not understand or know the true murderous intent of the enemy; they were confident that they would be forgiven for their lives by not fleeing when they approached. The main shortcomings and errors that were seen in the recent enemy offensive on the population, of the Self-Defense measures are as follows:

|

Both pamphlets are aimed at educating the residents of the region, but both show a strong lack of knowledge of the population to which they are addressed: on the one hand, the language used in the guerrilla pamphlet is extremely sophisticated, showing that those who wrote it They wrote were people of high academic standing fighting for a Marxist ideal, but without the ability to express the same ideas in simple and direct language that could be easily understood by illiterate rural communities. On the other hand, the army's language is much more accessible to the residents, but it is not convincing due to the news that circulated in the area due to the army's actions. In both cases, an indigenous interpretation of the events is missing: there is no reference to the beliefs of the Ixils, much less written in their native language that would convey the messages effectively.

Then, the army report on the results of Operation Sofia of August 19, 1982, indicates that it "was successful both in the military aspect and in that of psychological operations. During the entire operation, pressure was maintained on the enemy, there were no casualties due to combat or administrative, having managed to cut the logistical support bases in the area, having managed to destroy 10 large mailboxes and deactivate thirty-three during the reported period. traps, fifteen underground dwellings all of which were destroyed. In population control operations, it was possible to remove great support from the guerrilla, managing to evacuate one hundred and twenty-two people to the municipality of Nebaj, who remained under the control of the Military Detachment of said municipality. The First Company of paratroopers formed a detachment in the Salquil Village in order to gather the residents of the different cantons in this village, reporting having gathered and controlled seven hundred and thirty-seven people, who are receiving help and security from the Gumarkaj Task Force. On August 5, two hundred and forty-six people from Salquil and its surroundings presented themselves to the military authorities of the municipality of Aguacatán, requesting protection.

Population Communities in Resistance

In the period 1981-82, in which more than four hundred towns and villages were razed and thousands of Guatemalans murdered, the reaction of the survivors trapped between two fires was to flee, or put themselves under the control of the Army and forced to participate in the Civil Self-Defense Patrols (PAC) or relocated to the "model villages", where they were concentrated. Some fifty thousand totally dispossessed people escaped to jungle areas of the department of Quiché, spending those years hidden from the outside world and outside of government control.

A decade later, approximately half were still there, although the Army offensives between Amachel and Sumal between 1987 and 1989 forced some five thousand people to leave there. Later, others established themselves outside the CPR, north of Uspantán. In mid-1992, there were about seventeen thousand inhabitants of the CPR of the Sierra and about six thousand in Ixcán, or an approximate total of twenty-three thousand people.

Ethnically, the CPR of Ixcán were mostly K'iche' while in the communities of the Sierra they were mostly Ixil, the rest being Chajuleños, Cotzaleños and K'iche's, as well as Ladinos. The communities visited highlighted the equal coexistence of their members of all origins.

During 1992 and 1993, numerous national and international observers visited the CPRs both in the Sierra and in Ixcan, indicating that "they were unarmed civilians living in great poverty and that they could barely survive by planting corn, beans, and raising farm animals." —Christian Tomuschat Independent Expert for Guatemala of the United Nations |

In January 1994, the CPR of Ixcán made public their intention to settle peacefully as of February 2 in their previous locations between the Ixcán and Xalbal rivers on lands of the Ixcán Grande Cooperative, whose members are mostly members of the CPR, and invited the IACHR to verify their situation with regard to human rights. On March 9 and 10, 1994, the CPR were Quiché were visited by members of the Ibero-American Commission on Human Rights (IDEH); The communities visited were Santiaguito, San Luis, San Francisco, Los Altos and La Esperanza (Ixcán) and the CPRs in Cabá and Santa Clara (Sierra). The Commission also visited nearby towns in Centro Veracruz (Ixcán) and Asunción del Copón (Sierra), as well as "workers" of some of the CPR and met with military patrols operating in those territories. On these trips the Delegation was also able to observe other towns in the area, as well as the barracks abandoned by the Army in Tercer and Cuarto Pueblo.

Lost Communities

The lost communities were isolated spontaneous settlements, which were outside the CPR system but close to them in practically isolated areas of El Quiché and Alta Verapaz, and which were in terrible survival conditions. These populations consciously decided to relocate to remote areas not considered insurgency and develop their lives outside the reach of armed groups, patrols and the Army, developing a subsistence economy, and avoiding attracting public attention. Some of the families that comprise it were part of the CPR in the past and have decided to relocate outside the conflict zone. These isolated communities were located in the Uspantán area, where there were between sixty and ninety communities of this type with a population that varied between thirty to fifty families each.

Geography

Hydrography

The department of Quiché is bathed by many rivers. Among the main ones, the Chixoy River or Negro River stands out, which runs through the municipalities of Sacapulas, Cunén, San Andrés Sajcabajá, Uspantán and Canillá, and has the Chixoy hydroelectric dam; the Blanco River and the Pajarito (in Sacapulas); the Azul River and the Los Encuentros River (in Uspantán); the Sibacá and Cacabaj rivers (in Chinique); and the Rio Grande or Motagua in Chiché.

There are also the Lemoa and La Estancia lagoons (in Santa Cruz del Quiché), and the San Antonio lagoon (in San Antonio Ilotenango).

Orography

The geographical configuration of Quiché is quite varied. Its altitudes range between 2310 and 1196 m s. n. m.; Consequently, its climates are very variable, with cold and temperate predominating, although there are some areas with a warm climate. However, there are heights of up to 3000 m s. n. m. in a system of mountain ranges that crosses the department from west to east.

This department is crossed by three different orographic systems: the Chamá mountain range (to the north), the Cuchumatanes mountain range (to the center) and the Chuacús mountain range (to the southeast), which determines the different climates, which manifest themselves from the cold temperate ones to the warmest ones.

It also has other important mountains, which are: those of Joyabaj (in the municipality of the same name); and that of La Cumbre and that of Chuxán (in San Bartolomé Jocotenango).

Among the hills are Poquijil (in Chichicastenango), Pocbalam (in San Bartolomé Jocotenango), Pachum (in Joyabaj) and Los Achiotes (in San Andrés Sajcabajá).

Zones of plant life

In the department of Quiché there are seven zones of plant life, according to the classification proposed by Holdridge in 1978:

- bs-S: subtropical dry forest

- bh-S (t): tempered subtropical forest

- bh-S (c): warm subtropical humid forest

- bo-S: subtropical rainforest

- bmh-S (c): very humid warm subtropical forest

- bh - MB: wet mountain forest under subtropical

- bmh-MB: very humid subtropical mountain forest

Communication routes

The department of Quiché is interconnected, through national route No. 15, which in the village of Los Encuentros, municipality of Sololá, connects with the Inter-American Highway CA-1; Route No. 15 that starts from Los Encuentros, crosses Chichicastenango, Santa Cruz del Quiché, San Pedro Jocopilas, Sacapulas and Cunén and reaches Chajul. Just as Highway 7W, which originates in the department of Alta Verapaz, crosses Quiché approximately from east to west and ends in the department of Huehuetenango.

It also has several departmental and municipal roads that link its municipalities to each other, although most of them are in poor condition or unpaved.

Geology

Types of soil that stand out in the department of Quiché:

- JKfs: Jurassic-cretaceic, formation All Saints, Jurassic Superior-neocomian (red pipes), includes the formation San Ricardo.

- Qa: Quaternary Floods

- Tsp: upper oligocene-pliocene tertiary, predominantly continental: includes formations Cayo, Armas, Caribbean, Hereria, Bacalar and White Maris.

- Pe: paleocene-eocene, marine sediments.

- PC: pearmic, Chochal formation (carbonates).

- Kts: Cretaceous-terciario, Sepur formation, Spanish-American. Predominantly marine cystic sediments. It includes formations Toledo, Reforma y Cambio and Veraoaz group.

- Ksd: Cretaceous, neo-Caomian-campanian carbonates, includes Coban, Ixcoy, Campur, Sierra Madre and Yojaa group formations.

- Qp: quaternary, fillings and thick covers of pumice ash of diverse origin.

- Tv: tertiary, undivided volcanic rocks. Predominantly mio-pilocene. It includes tobas, lava coladas, lahárico material and volcanic sediments.

- I: Plutonic undivided rocks, Includes preperimeric-age diorite granites. Cretaceous and tertiary.

- TT: ultrabasic rocks of unknown age, predominantly serpetinite. Pre-Maestrichtian part.

- Pzm: paleozoic, metamorphic rocks without dividing. Philites, chlorophic and diorite schisms and prepermal, cretaceous and tertiary granites.

Current land use

In the department of Quiché, due to its climate, types of soil and the topography of the land, its inhabitants plant a great diversity of annual, permanent or semi-permanent crops, including cereals, vegetables, fruit trees, coffee, cane. sugar, etc. Furthermore, due to the qualities that the department has, some of its inhabitants raise various types of livestock.

The existence of forests, whether natural, integrated management, mixed, etc., composed of various tree, shrub or creeping species give the department a special touch in its ecosystem and environment, turning it with that natural grace into one of the typical places to be inhabited by not only national, but also foreign visitors. It is in this way that the reader can form an idea of how in this department the use of land is sometimes used intensively and other times passively.

Productive capacity of the land

To show what productive capacity of land is available in this department, in Guatemala according to the US Department of Agriculture, there are 8 classification classes of productive capacity of the land, based on the effects combined climate and permanent soil characteristics. Of these 8 agrological classes, I, II, III and IV are suitable for agricultural crops with specific cultural practices of use and management; classes V, VI, and VII can be dedicated to perennial crops, specifically natural or planted forests; while class VIII is considered suitable only for national parks, recreation and for the protection of soil and wildlife.

In Quiché, five of the eight indicated agrological classes are represented, with classes VII, IV and VI predominating.

Customs and traditions

Their religious ceremonies are generally presided over by Mayan priests, who are specialized people hired by the neighbors to serve as intermediaries before the beings from beyond (God, Jesus Christ, the saints, the World God, the spirits of the ancestors, etc.) through a symbolic payment. These ceremonies are carried out both inside and outside the church, and even in the mountains in special places called "quemaderos." In these ceremonies they bring offerings such as incense, copal, pom, liquor (guaro), candles and other things. We also have the Canilla fair Among the customs and traditions of Canillá we have the Titular fair from December 7 to 13 in honor of the Virgin of Concepción, dates on which Religious, Sports, Cultural and Social activities take place. Such as: Jaripeo, the horse races, the Livestock Fair, the zarabanda dance, costume dance (invitation for both men and women), burning of bulls, without distinguishing a particular costume that is characteristic of men or women. women; Carnival Day, this activity takes place on the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday, which takes place in schools, February 14, Day of Love and Friendship, Holy Week, processions are held on the Fridays before Holy Week, there are crosses, it is customary delight in typical food such as: dried fish wrapped in egg, curtidos, torrejas, bread with honey and chicken broth. But in the Chijoj village, during Holy Week, the fair of this town is celebrated, developing its social, cultural, sports and religious activities, Mother's Day, May 10, it is worth mentioning that this celebration is a very important holiday in each and every one of the 30 rural communities that make up the municipality of Canillá, communities that have a school for which they celebrate with marimbas, meals, bombs, rockets, serenades, September 15 celebration of the national holidays in which various activities are carried out such as: The torch will be brought to the departmental capital towards Canillá as a symbol of freedom, a civic parade, a baited stick or animal, soccer and basketball games, and cultural activities. Celebration of San Lucas Day (livestock farmer's day) this activity takes place on October 18 for which different events take place such as: Jaripeo, livestock farmer's dance, Saints' Day, it is customary to go to clean and decorate the mausoleums of the municipal cemetery. On the second of November, it is customary to take food to the cemetery such as: Creole chicken in miltomate sauce, cooked Güisquil, squash and jocotes in honey, Christmas, New Year's and Social Dances.

Folk Dances

Quiché has two important dance centers. One is in Santa Cruz del Quiché, its head, and the other is Joyabaj. In Santa Cruz the main dance is that of La Culebra, in Chichicastenango that of the Torito, and in Joyabaj that of the Palo Volador, called by its inhabitants as Palo de los Voladores. In their other municipalities they also perform the dances of El Venado, Tantuques, El Torito, Mexicanos, La Conquista and Convites.

Demography

Population of Quiché according to municipality

| N. | Municipality | Population Census 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chichicastenango | 141.567 |

| 2 | Ixcan | 99.470 |

| 3 | Joyabaj | 82,369 |

| 4 | Santa Cruz del Quiché | 78.279 |

| 5 | Nebaj | 72.686 |

| 6 | Uspanstan | 65,872 |

| 7 | Sacapulas | 52.620 |

| 8 | Chajul | 46.658 |

| 9 | How | 41,455 |

| 10 | Chicaman | 39.731 |

| 11 | Zacualpa | 32.750 |

| 12 | San Pedro Jocopilas | 31.950 |

| 13 | San Juan Cotzal | 31,532 |

| 14 | Chiché | 29.646 |

| 15 | San Antonio Ilotenango | 25.590 |

| 16 | San Andrés Sajcabajá | 24,981 |

| 17 | San Bartolomé Jocotenango | 13,568 |

| 18 | Canillá | 12,172 |

| 19 | Chinique | 11,382 |

| 20 | Pachalum | 8.839 |

| 21 | Patzité | 6,144 |

| - | 949,261 |

Development

The human development report published in 2022, The speed of change, a territorial view of human development 2002 – 2019, where the change and progress that has occurred in the country between 2002 was observed and 2019. The Department of El Quiche is ranked twenty-first among the 22 departments of Guatemala. Being one of the departments with the greatest growth between 2002 and 2018, going from 0.433 to 0.564. Quiche has 12 municipalities with Medium HDI and 9 with Low HDI. Pachalum has the highest HDI with 0.661 and the lowest is San Pedro Jocopilas with 0.507.

| N. | Municipality | IDH 2018 | IDH 2002 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pachalum | 0.661 | 0.5533 |

| 2 | Santa Cruz del Quiché | 0.638 | 0,543 |

| 3 | Chinique | 0,613 | 0.496 |

| 4 | Nebaj | 0.6612 | 0.475 |

| 5 | How | 0,592 | 0.444 |

| 6 | Ixcan | 0.578 | 0.451 |

| 7 | San Juan Cotzal | 0.5577 | 0.429 |

| 8 | Chichicastenango | 0.576 | 0.442 |

| 9 | Canillá | 0.574 | 0.449 |

| 10 | Sacapulas | 0.5564 | 0.437 |

| 11 | Patzité | 0.558 | 0.437 |

| 12 | Uspanstan | 0.552 | 0.418 |

| 13 | Chiché | 0.548 | 0.427 |

| 14 | San Antonio Ilotenango | 0,542 | 0,401 |

| 15 | Chicaman | 0.541 | 0,404 |

| 16 | Chajul | 0.537 | 0,404 |

| 17 | San Andrés Sajcabajá | 0.530 | 0.381 |

| 18 | Zacualpa | 0.527 | 0.410 |

| 19 | Joyabaj | 0.515 | 0,392 |

| 20 | San Bartolomé Jocotenango | 0,513 | 0.354 |

| 21 | San Pedro Jocopilas | 0.507 | 0.376 |

| - | 0.5564 | 0,433 |

| N. | Municipality | IDH According to Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Education | Level of Life | ||

| 1 | Pachalum | 0.888 | 0.5501 | 0.649 |

| 2 | Santa Cruz del Quiché | 0,804 | 0,407 | 0,594 |

| 3 | Chinique | 0.815 | 0.466 | 0.606 |

| 4 | Nebaj | 0.835 | 0.465 | 0.591 |

| 5 | How | 0,803 | 0,452 | 0.570 |

| 6 | Ixcan | 0.735 | 0.444 | 0,593 |

| 7 | San Juan Cotzal | 0,800 | 0.428 | 0.562 |

| 8 | Chichicastenango | 0.846 | 0.384 | 0.589 |

| 9 | Canillá | 0.777 | 0.409 | 0,594 |

| 10 | Sacapulas | 0.806 | 0.386 | 0.576 |

| 11 | Patzité | 0.761 | 0,400 | 0.570 |

| 12 | Uspanstan | 0.771 | 0.390 | 0.558 |

| 13 | Chiché | 0.774 | 0.366 | 0.580 |

| 14 | San Antonio Ilotenango | 0.799 | 0.352 | 0.568 |

| 15 | Chicaman | 0.742 | 0.384 | 0.555 |

| 16 | Chajul | 0.763 | 0.366 | 0.555 |

| 17 | San Andrés Sajcabajá | 0.759 | 0.356 | 0.552 |

| 18 | Zacualpa | 0.785 | 0.331 | 0.5564 |

| 19 | Joyabaj | 0.796 | 0.308 | 0.557 |

| 20 | San Bartolomé Jocotenango | 0.771 | 0.320 | 0.546 |

| 21 | San Pedro Jocopilas | 0.724 | 0.332 | 0.544 |

| - | 0.788 | 0,392 | 0.574 | |

Population living in the department according to HDI

| N. | Municipality | IDH 2018 | Population | According to Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pachalum | 0.661 | 8.839 | 622.017 |

| 2 | Santa Cruz del Quiché | 0.638 | 78.279 | |

| 3 | Chinique | 0,613 | 11,382 | |

| 4 | Nebaj | 0.6612 | 72.686 | |

| 5 | How | 0,592 | 41,455 | |

| 6 | Ixcan | 0.578 | 99.470 | |

| 7 | San Juan Cotzal | 0.5577 | 31,532 | |

| 8 | Chichicastenango | 0.576 | 141.567 | |

| 9 | Canillá | 0.574 | 12,172 | |

| 10 | Sacapulas | 0.5564 | 52.620 | |

| 11 | Patzité | 0.558 | 6,144 | |

| 12 | Uspanstan | 0.552 | 65,872 | |

| 13 | Chiché | 0.548 | 29.646 | 327.243 |

| 14 | San Antonio Ilotenango | 0,542 | 25.590 | |

| 15 | Chicaman | 0.541 | 39.731 | |

| 16 | Chajul | 0.537 | 46.658 | |

| 17 | San Andrés Sajcabajá | 0.530 | 24,981 | |

| 18 | Zacualpa | 0.527 | 32.750 | |

| 19 | Joyabaj | 0.515 | 82,369 | |

| 20 | San Bartolomé Jocotenango | 0,513 | 13,568 | |

| 21 | San Pedro Jocopilas | 0.507 | 31.950 | |

| - | 0.5564 | |||

Language

Quiché is one of the most populated departments in the nation and is the territory that - along with Huehuetenango - has the most languages. The Uspantec language is spoken in the municipality of Uspantán, Ixil in Nebaj, Chajul and San Juan Cotzal, Sacapulteco in Sacapulas, Kekchí in the northern part of the department, while Kiché is spoken in the southern part.

Although Spanish is the official language of the Republic of Guatemala and the department, a large part of the population uses it as a second language for commerce and tourism. Even some inhabitants do not have extensive knowledge of the aforementioned language, because they did not have access to primary education.

Economy

Agricultural production

Agriculture is one of the main areas in the life of its inhabitants, since the variety of climates, combined with the large number of rivers that run through its territory, contribute to its production being varied and abundant, its main ones being items: corn, wheat, beans, potatoes, beans, peas and on a smaller scale coffee, sugar cane, rice and tobacco. There are also large forests where precious woods abound. We can also find the most valuable products in this department.

Livestock production

In almost all municipalities there is raising of cattle, horses, sheep and goats, especially in the municipalities of Santa Cruz Quiché, Nebaj, San Juan Cotzal, Chajul and Uspantán. Sheep cattle are found mainly in areas with colder climates.

Industrial production

Something very important that needs to be highlighted is the production of the best-known Black Salt, gem or stone salt, which the indigenous people of Sacapulas extract from the mines. It is known that its subsoil is rich in minerals, with known mines of iron, silver, marble, lead, etc.

Artisanal production

Quiché is one of the most important departments in terms of its artisanal production. The production of traditional cotton and wool fabrics stands out. The cotton ones, woven by women on backstrap looms; and the wool ones, by men on foot looms, although the small pieces such as backpacks, bags and caps, are woven by hand, with a needle.

Another important craft is the production of high-quality palm hats. Women make braids at any time, at home or on the roads when they go to the market. These braids are delivered to the workshops where the hats are sewn. They also make musical instruments, rocketry, traditional ceramics, leather goods, basketry, rigging, wooden furniture and carving of masks.

Poverty

In the department of Quiché (100% of its population) there is 74.7% in poverty or 41.8% in extreme poverty according to UNDP 2014 data. [1]

Tourist and archaeological centers

The municipality of Chichicastenango has been for years one of the most important towns on the tourist circuit of Guatemala, as it is where tourists can admire in all its meaning the religious faith of the native peoples descended from the ancient Mayans.

In Santa Cruz del Quiché there are the Chocoyá and Pachitac spas, while the Agua Tibia and El Chorro rivers pass through Chinique, and in Nebaj, the Las Violetas river. Also in Nebaj are the El Boquerón and Las Clavelinas viewpoints.[citation required]

4 km from Santa Cruz del Quiché is Gumarcaaj, which was the ancient capital of the Quiché Kingdom. It has a museum of pre-Hispanic art and a visitor center. The ruins of the Mayan city of Xutixtiox are located near Sacapulas.

La Laguna de Lemoa, located in the village of the same name, was declared suitable for the sport of fishing. The Pascual Abaj hill - in honor of Pascual Abaj - is a site of pre-Hispanic celebrations.

At the cinema

- The film Gerardi, the movie, produced by the Office of Human Rights of the Archbishop of Guatemala and Moralejas films and starring Jimmy Morales describes the most difficult moments of the Guatemalan Civil War in the department of Quiché, when the villages are being attacked and rooted and the Catholic church is being intimidated and forced to take sides. Monsignor Gerardi was a bishop in that department, and different locations were used to film the film.

Geographical location

| North: Chiapas, state of Mexico | Northeast: Peten, Guatemala department | |

| West: Huehuetenango, department of Guatemala |  | This: Alta Verapaz, department of Guatemala |

| South: Sololá, department of Guatemala |

Contenido relacionado

Annex: Municipalities of the province of Huesca

Length

Valdunciel Causeway