Quetzalcoatlus

Quetzalcoatlus, named after the Aztec deity Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, is an extinct genus of pterodactyloid pterosaurs from the Late Cretaceous in North America (Maastrichtian, about 68 years ago). -66 million years), and one of the largest known flying animals of all time. It was a member of the azhdarchids, a family of advanced toothless pterosaurs with rigid, unusually long necks.

Description

Cranial material (from an as yet unnamed minor species) shows that Quetzalcoatlus had a very sharp and sharp beak, contrary to the first reconstructions that showed a blunt snout, based on the inadvertent inclusion of material from the jaw of another species of pterosaur, possibly a tapejarid or a form related to Tupuxuara. A cranial crest was present but its exact shape and size are still unknown.

Size

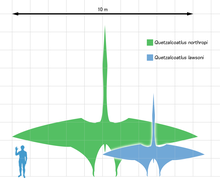

When it was discovered, scientists estimated that the largest Quetzalcoatlus fossils came from an individual with a wingspan as large as about 15.9 meters, choosing the average of three extrapolations of the proportions of others pterosaurs that gave estimates of 11, 15.5 and 21 meters, respectively. In 1981, later studies lowered those measurements to 11-12 meters. More recent estimates based on greater knowledge of the proportions of azhdarchids place their wingspan at 10-11 meters.

Mass estimates for giant azhdarchids are extremely problematic because there are no species that share a similar size or body shape, and consequently published results vary widely. While some studies have yielded extremely low numbers For the weight of Quetzalcoatlus, as much as just 70 kilograms for a 10-meter individual, most estimates published in the 2000s have been higher, tending toward 200 - 250 kilograms.

Discovery and species

The first fossils of Quetzalcoatlus were discovered in Texas, in the Javelina formation in Big Bend National Park (dated to about 68 million years ago in the Maastrichtian) in 1971 by a student graduate of geology from the Jackson School of Geosciences at the University of Texas at Austin, Douglas A. Lawson. The specimen consisted of a partial wing (in pterosaurs they are composed of the arm and the elongated fourth finger), from an individual later estimated to have a wingspan of about 10 meters. Lawson discovered a second site of the same age, near forty kilometers from the first, where between 1972 and 1974 he and Professor Wann Langston Jr. of the Texas Memorial Museum unearthed three fragmentary skeletons of much smaller individuals. Lawson announced the find in a 1975 article in the journal Science. That same year, in a subsequent letter in the same publication, he made the original large specimen, TMM 41450-3, the holotype of a new genus and species, Quetzalcoatlus northropi. The genre refers to the Mexica deity Quetzalcoatl, represented as a feathered snake. The species name honors John Knudsen Northrop, the founder of the Northrop Corporation, who was interested in tailless flying-wing aeronautical designs similar to Quetzalcoatlus. At first it was assumed that the lesser specimens were juveniles or subadult forms of the older type. Later, when more remains were found, it was considered that they could be from a separate species. This possible second Texas species was provisionally named Quetzalcoatlus sp. by Alexander Kellner and Langston in 1996, indicating that its status was too uncertain to give it a full species name. The specimens are more complete than the holotype ofQ. northropi, and include four partial skulls, although they are much less massive, with an estimated wingspan of 5.5 meters.

The holotype specimen of Q. northropihas yet to be described. Mark Witton and colleagues in 2010 have deemed the remains indistinguishable from its Romanian contemporary Hatzegopteryx. IfQ. northropi is complete enough to be distinguished from other pterosaurs (or would otherwise be a nomen dubium), Hatzegopteryx may represent the same animal. It is likely that large pterosaurs such asQ. northropi may have had wide transcontinental geographic ranges, making their presence in both North America and Europe unsurprising. Mark Witton et al. noted that the cranial material of Hatzegopteryx > and Q. sp. They differ too much to be considered the same animal, which would make it probable that if Q. sp., is not identical to Quetzalcoatlus northropi, it then represents a different genus.

A cervical vertebra from an azhdarchid, discovered in 2002 in the Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation, may also belong to Quetzalcoatlus. The specimen (BMR P2002.2) was accidentally recovered when it was included in a plaster-covered block prepared to transport part of a tyrannosaurid specimen. Despite this association with the remains of a large carnivorous dinosaur, the vertebra shows no evidence of having been chewed by the dinosaur. The bone comes from an individual azhdarchid pterosaur with an estimated wingspan between 5 to 5.5 meters.

Paleobiology

Quetzalcoatlus was abundant in Texas during the Lanciano in a fauna dominated by Alamosaurus. The Alamosaurus-Quetzalcoatlus association i> probably represents semiarid interior plains. Quetzalcoatlus had precursors in North America and its apparent emergence and expansion may represent the extension of its preferred habitat rather than an immigration event, as some experts have suggested.

Food

There have been several different ideas proposed about the lifestyle of Quetzalcoatlus. Because the area of the fossil site was four hundred kilometers from the nearest coast of the time and there were no indications of large rivers or deep lakes near the end of the Cretaceous, Lawson in 1975 rejected a piscivorous lifestyle, suggesting instead that Quetzalcoatlus was a scavenger like the modern marabou, feeding on the carcasses of titanosaur sauropods such as Alamosaurus. Lawson found remains of the giant pterosaur while searching for bones of this dinosaur, which formed an important part of its ecosystem.

In 1996, Thomas Lehman and Langston ruled out the scavenger hypothesis, pointing out that the lower jaw tilted so strongly downward that, even when it closed completely, there was a space of more than five centimeters between it and the upper jaw, very distinct from the hooked beaks of specialized scavengers. They suggested that with its long neck vertebrae and long toothless jaws Quetzalcoatlus fed like modern skimmers, catching fish in flight while riding the waves with its beak. Although this style of fishing became widely accepted, was not subject to rigorous scientific research until 2007, when a study showed that for large pterosaurs there was no viable method of surface fishing because the energy costs would be too high from excessive trawling. In 2008 the Pterosaur researchers Mark Paul Witton and Darren Naish published an examination of possible feeding habits and ecology of azhdarchids. Witton and Naish noted that many azhdarchid remains are found in continental deposits far from the seas or other large bodies of water required for fishing. Additionally, the anatomy of the beak, jaw and neck are different from any animal that catches fish in mid-flight. Therefore, they concluded that azhdarchids were probably terrestrial predators, similar to modern storks, and probably hunted small vertebrates on land or in small streams. Although Quetzalcoatlus, like other pterosaurs, was a quadruped when on land, Quetzalcoatlus and other azhdarchids had limb proportions more similar to those of modern running hoofed mammals than their relatives. minors, implying that they were uniquely adapted to a more terrestrial life.

Flight

The nature of flight in Quetzalcoatlus and other giant azhdarchids is poorly understood. Its method of flight depends largely on its weight, which has been the subject of discussion, with very different masses indicated by different scientists. Some researchers have suggested that these animals employed slow gliding flight, while others have concluded that their flight was fast and dynamic. In 2010, Donald Henderson stated that the mass ofQ. northropihad been underestimated, even in the highest estimates, and was too large to have achieved powered flight. Henderson noted that it may have been a flightless pterosaur.

Paul MacCready carried out an aerodynamics experiment to examine the flight of Quetzalcoatlus in 1986. He built a model of a flying machine or ornithopter with a simple computer serving as an autopilot. The model flew successfully with a combination of gliding and flapping of the wings; however, the model was half the size of the real animal and was based on the old weight estimate of about 80 kilograms, much less than the more modern ones. estimates of about 200 kg.

Classification

Below is a cladogram showing the phylogenetic position of Quetzalcoatlus within Neoazhdarchia according to Andres and Myers (2013).

| Neoazhdarchia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In popular culture

Quetzalcoatlus has been depicted in documentaries, both in cinemas and on television, since the 1980s. The Smithsonian planned to build a working model of Q. northropi which was the subject of the 1986 IMAX documentary On the Wing, shown at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. It has also appeared on television shows such as Walking with Dinosaurs from the BBC in 1999 and Clash of the Dinosaurs from Dangerous Ltd. in 2009. The latter program featured features invented by the producers to accentuate the entertainment, including showing Quetzalcoatlus with the ability to use ultraviolet vision to locate dinosaur urine marks when hunting in the air. It also appeared in the 2011 documentary March of the Dinosaurs, where It was erroneously depicted as a clawless bipedal scavenger, and in the 2009 miniseries Animal Armageddon, where it was correctly reconstructed with pycnofibers (hair-like filaments that covered pterosaurs).

In June 2010, several life-size models of Q. northropiwere displayed on the South Bank in London as the centerpiece of the Royal Society's 350th anniversary exhibition. The models, which include individuals both on the ground and flying with wingspans of 11 meters, were intended to help create interest in science among the public. The models were created by scientists from the University of Portsmouth, including David Martill, Bob Loveridge and Mark Witton, and engineers Bob and Jack Rushton from Griffon Hoverwork. The exhibition presented to the public the most accurate models of pterosaurs ever constructed, taking into account anatomical and footprint evidence based on skeletal and footprint fossils of related pterosaurs.

In modern technological designs

In 1985, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and AeroVironment used Quetzalcoatlus northropi as the basis of an experimental ornithopter UAV. They produced a half-scale model weighing 40kg, with a wingspan of 18 metres. Coincidentally, Douglas A. Lawson, who discoveredQ. northropiin Texas in 1971, named it after John "Jack" Northrop, a famous developer of tailless aircraft in the 1940s. The replica ofQ. northropiincorporated a flight control system or autopilot which processed pilot commands and sensor information, implementing several feedback circuits, and sent command signals to its various servo drives. It is exhibited at the National Air and Space Museum.

Contenido relacionado

Leopardus wiedii

Cobra

Carcharocles megalodon

Thunnus

Pusa sibirica