Qing Dynasty

The dynasty Qing (pronounced 'ching' /tɕʰíŋ/; Chinese: 清朝 W-G Ch'ing Ch'ao, PY Qīng Cháo), officially Great Qing (Chinese: 大清; Dà Qīng), or State of the Great Qing (Manchu: ᡩᠠᡳᠴᡳᠩ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ Daicing Gurun), also called the Qing Empire or Manchu Dynasty, was the last Chinese imperial dynasty, ruling the present country from 1644 to 1912. It was preceded by the Ming dynasty and succeeded by the Republic of China.The multicultural Qing empire lasted nearly three centuries and formed the territorial basis for the state modern chinese.

The dynasty was founded by the Yurchen clan of Aisin-Gioro in Manchuria, where in the early 17th century they established a multi-ethnic state with capital at Mukden. In 1644, taking advantage of the collapse of the Ming dynasty as a result of Li Zicheng's revolt, the Manchu general Dorgon crossed the Great Wall with Chinese help and invaded China, capturing Beijing in 1645. Dorgon proclaimed his nephew Shunzhi emperor of China, thus began the rule of the Qing over all of China. The dynasty consolidated its control over China rapidly, reaching its peak during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (r.1735-1796), after which it began a gradual decline.

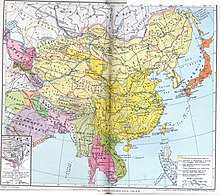

During the reign of the first Qing emperors, China experienced a period of internal stability and unprecedented demographic, territorial and economic growth. Qianlong's conquests expanded the Qing empire into Central Asia, doubling its size. The population rose from about 130 million to about 400 million, but taxes and government revenues, set at very low levels, stagnated, which by the turn of the century XIX led to a fiscal crisis. Territorial and population growth, affected by the government's lack of fiscal resources, overburdened the government's ability to effectively control China's vast territory. Corruption became endemic; successive rebellions tested the legitimacy of the government, and the ruling elites were unable to respond effectively to the increasing changes in the world landscape, where the western powers increasingly demanded the commercial opening of China.

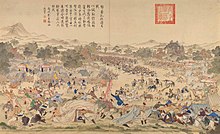

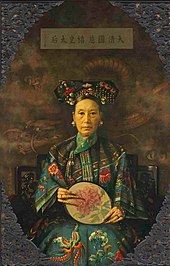

After the First Opium War (1839-1842), Western powers imposed unequal treaties, free trade, extraterritoriality, and foreign-controlled ports. The Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) and the Dungan Revolt (1862-1877) in Central Asia killed some 20 million people, most of them in war-induced famines. After the Second Opium War (1856-1860), the Western powers forced China to partially reform, and helped the Qing government to pacify its internal rebellions. Despite these disasters, in the Tongzhi Restoration of the 1860s, Han elites rallied in defense of the Confucian order and the Qing rulers. The initial gains of the Self-Strengthening Movement were lost in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1895, in which the Qing lost their influence over Korea and possession of Taiwan. The Qing tried to reorganize their military, but the ambitious Hundred Days' Reform of 1898 was defeated in a coup by Empress Dowager Cixi, leader of the conservative faction of the government. When the struggle for concessions by foreign powers triggered the Boxer Rebellion, the foreign powers intervened militarily in China again; Cixi declared war on them, which led to their defeat and the flight of the imperial court to Xi'an.

After signing the Boxer Protocol in 1900, the Qing imperial government initiated unprecedented fiscal and administrative reforms, including elections, a new legal code, and the abolition of the millennial examination system. Sun Yat-sen and other revolutionaries competed with reformist monarchists like Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao to transform the Qing Empire into a modern nation. After the death of Cixi and the Guangxu Emperor in 1908, the conservative faction at court tried to obstruct the reforms. The Wuchang uprising on October 11, 1911 led to the Xinhai Revolution. The last emperor, Puyi, abdicated on February 12, 1912, ending the Empire and ending more than 2,000 years of Chinese imperial tradition.

Names

Nurhaci declared himself the "brilliant Khan" of the Jin state (literally "gold"; known in Chinese historiography as the "Later Jin") in honor of both the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty of the XII-XIII as his clan Aisin-Gioro (Aisin is Manchu for Chinese 金 (jīn, "gold")). His son Hong Taiji renamed the dynasty Great Qing in 1636. There are conflicting explanations as to the meaning of Qīng (literally, "clear"). or "pure"). The name may have been selected in reaction to the Ming dynasty name (明), which consists of the Chinese characters for "sun" (日) and "moon" (月), both associated with the fire element of the Chinese zodiac system. The character Qīng (清) is made up of “water” (氵) and “blue” (青), both associated with the element of water. This association would justify the Qing conquest as the defeat of fire by water. The water images of the new name may also have had Buddhist connotations of insight and enlightenment and connections to the Bodhisattva Manjusri. The Manchu name daicing, which sounds like a phonetic representation of Dà Qīng or Dai Ching, may in fact be derived from a Mongolian word ᠳᠠᠢᠢᠴᠢᠨ дайчин meaning "warrior". Daicing gurun may have meant 'warrior state', a play on words only intelligible to Manchus and Mongols. By the latter part of the dynasty, however, even the Manchus themselves had forgotten this possible meaning.

After conquering "China of their own", the Manchus identified their state as "China" (中國, Zhōngguó; "Middle Kingdom"), and referred to it as Dulimbai Gurun in Manchu (Dulimbai means "central" or "middle", gurun means "nation" or "state"). The emperors equated the lands of the Qing state (including present-day northeast China, Xinjiang, Mongolia, Tibet, and other areas) as "China" in the Chinese and Manchu languages, defining China as a multi-ethnic state and rejecting the idea that "China" only meant Han areas. The Qing emperors proclaimed that both Han and non-Han peoples were part of "China." They used "China" and "Qing" to refer to their status in official documents, international treaties (as the Qing was known internationally as "China" or "Chinese Empire") and foreign affairs, and the "Chinese language" (in Manchu: Dulimbai gurun i bithe) included Chinese, Manchu and Mongolian, and "Chinese people" (中國之人 Zhōngguó zhī rén; Manchu: Dulimbai gurun i niyalma) referred to all the subjects of the empire. In the Chinese versions of their treatises and world maps, the Qing government used "Qing" and "China" interchangeably.

History

Nurhaci and the formation of the Manchu state

The Qing dynasty was founded not by the Han Chinese, who make up the majority of the Chinese population, but by a sedentary farming people known as the Jurchen, a Tungusic people who lived in the region that now includes the Chinese provinces of Jilin and Heilongjiang. The Manchus are sometimes mistaken for a nomadic people, but they were not.

What would become the Manchu state was founded by Nurhaci, the chief of a minor Jurchen tribe, the Aisin Gioro, in Jianzhou at the turn of the century XVII. Nurhaci may have spent time in a Chinese household in his youth, becoming fluent in Chinese and Mongolian, and reading the Chinese novels Romance of the Three Kingdoms and At the Water's Edge. Originally a vassal of the Ming emperors, Nurhaci embarked on an intertribal feud in 1582 that turned into a campaign to unify nearby tribes. By 1616, he had sufficiently consolidated Jianzhou to be able to proclaim himself Khan of the Great Jin in reference to the earlier Jurchen dynasty. By the end of the 16th century, Nurhaci, originally a Ming Dynasty vassal, began to organize the 'Eight Banners,' military and social units that included Yurchen, Han Chinese, and Mongol elements. Nurhaci formed the Yurchen clans into a unified entity, which he renamed the Manchus.

When the Jurchens were reorganized by Nurhaci into the Eight Banners, many Manchu clans were artificially created as a group of unrelated people who founded a new Manchu clan (mukun) using a name of geographical origin. as a place name for their hala (clan name). Irregularities about the origin of the Jurchen and Manchu clan led the Qing to try to document and systematize the creation of histories for the Manchu clans, including the fabrication of a comprehensive legend about the origin of the Aisin Gioro clan by taking northeast mythology.

Moving his court from Jianzhou to Liaodong gave Nurhaci access to more resources; it also brought him into close contact with the Khorchin Mongol domains on the Mongolian plains. Although by this time the once united Mongol nation had long since fragmented into individual and hostile tribes, these tribes still posed a serious security threat to the Ming borders. Nurhaci's policy towards the Khorchin was to seek their friendship and cooperation against the Ming, securing their western border from a powerful potential enemy.

Furthermore, the Khorchin proved a useful ally in warfare, lending the Jurchen their expertise as cavalry archers. To secure this new alliance, Nurhaci initiated a policy of intermarriage between the Jurchen and Khorchin nobility, while those who resisted were met with military action. This is a typical example of Nurhaci's initiatives that eventually became the official policy of the Qing government. During most of the Qing period, the Mongols gave military assistance to the Manchus.

Some other important contributions of Nurhaci include ordering the creation of a Manchu script, based on the Mongolian script, after the earlier Jurchen script was forgotten (it had been derived from Khitan and Chinese). Nurhaci also created the civil and military administrative system that eventually became the Eight Banners, the defining element of Manchu identity and the basis for transforming the loosely woven Jurchen tribes into a nation.

Two years later, Nurhaci announced the "Seven Wrongs" and he openly renounced the suzerainty of the Ming overlordship to complete the unification of those Jurchen tribes still allied with the Ming emperor. After a series of successful battles, he moved his capital from Hetu Ala to successively larger captured Ming cities in Liaodong: first Liaoyang in 1621, then Shenyang (Mukden) in 1625.

In 1636, his son Hung Taiji began driving Ming forces out of Liaodong and declared a new dynasty, the Qing. In 1644, peasant rebels led by Li Zicheng conquered the Ming capital, Beijing. Instead of serving them, the Ming general Wu Sangui made an alliance with the Manchus and opened Shanhai Pass to the Eight Banner Armies led by Prince Regent Dorgon, who defeated the rebels and seized the capital. The resistance of the southern Ming and the rebellion of the three feudatories led by Wu Sangui extended the conquest of China proper for almost four decades and was not completed until 1683 under the Kangxi Emperor (1661-1722). The Qianlong Emperor's Ten Great Campaigns from the 1750s to the 1790s extended Qing control to all of Central Asia. The early rulers kept their Manchu customs, and although their title was emperor, they used the khan of the Mongols and were patrons of Tibetan Buddhism. They ruled using Confucian styles and bureaucratic government institutions and withheld imperial examinations to recruit Han Chinese to work under or alongside the Manchus. They also adapted the ideals of the tax system when dealing with neighboring territories.

There were too few ethnic Manchus to conquer China on their own, so they gained strength by defeating and absorbing the Mongols. More importantly, they added Han Chinese to the Eight Banners. The Manchu had to create a "Jiu Han jun" complete (Old Han Army) due to the large number of Han soldiers that were absorbed into the Eight Banners by capture and desertion. The Ming artillery was responsible for many victories against the Manchus, so the Manchus established an artillery corps made up of Han soldiers in 1641, and the swelling of Han Chinese numbers on the Eight Banners led in 1642 to the creation of all the Han soldiers. Eight Han banners. Armies of defected Ming Han Chinese conquered southern China for the Qing.

The Han people were instrumental in the Qing conquest of China. Han Chinese generals who defected to the Manchus often received women from the Aisin Gioro imperial family in marriage, while ordinary soldiers who surrendered often received non-royal Manchu women as wives. i> (Manchu) married Han Chinese in Liaodong. Manchu princesses Aisin Gioro also married the sons of Han Chinese officials.

Reign of Hong Taiji

Nurhaci's unbroken series of military successes ended in January 1626 when he was defeated by Yuan Chonghuan while besieging Ningyuan. He died a few months later and was succeeded by his eighth son, Hong Taiji, who emerged after a brief political struggle between other contenders to be the new Khan. Although Hong Taiji was an experienced leader and the commander of two banners at the time of his succession, his reign did not start well on the military front. The Jurchens suffered another defeat in 1627 at the hands of Yuan Chonghuan. As before, this defeat was due, in part, to the Ming's newly acquired Portuguese cannons.

To correct the technological and numerical disparity, Hong Taiji in 1634 created his own artillery corps, the ujen cooha (Chinese: 重軍, romanized: zhòngjūn) from among his existing Han troops who fired their own cannons in the European design with the help of Chinese metallurgical defectors. One of the defining events of Hong Taiji's reign was the official adoption of the name "Manchu" for the united Jurchen people in November 1635. In 1635, the Manchu Mongol allies were fully incorporated into a separate banner hierarchy under direct command. of the Manchus. Hong Taiji conquered the territory north of Shanhai Pass by the Ming Dynasty and Ligdan Khan in Inner Mongolia. In April 1636, the Mongol nobility of Inner Mongolia, the Manchu nobility, and the Han mandarins kept the Kurultai in Shenyang and recommended the Jin khan later to be the emperor of the great Qing empire. One of the Yuan dynasty jade seals has also been dedicated to the emperor (Bogd Setsen Khan) by the nobility. When it was said that the Yuan dynasty imperial seal was presented to him after the defeat of the last Great Khan of the Mongols, Hong Taiji renamed his state from "Great Jin" to "Great Qing" and elevated his position from Khan to Emperor, suggesting imperial ambitions beyond unifying Manchu territories. Hong Taiji then proceeded in 1636 to invade Korea again.

The name change from Jurchen to Manchu was done to hide the fact that the ancestors of the Manchus, the Jianzhou Jurchen, were ruled by the Chinese. The Qing dynasty carefully concealed the original editions of the Qing Taizu Wu Huangdi Shilu and Manzhou Shilu Tu (Taizu Shilu Tu) in the Qing palace, banned from public view because they showed the Manchu family Aisin Gioro had was ruled by the Ming dynasty and followed many Manchu customs that seemed "uncivilized" in the rear eyes. In the Ming period, Joseon Koreans referred to the Jurchen inhabited lands north of the Korean Peninsula, above the Yalu and Tumen rivers to form part of Ming China, as the & #34;top country" (sangguk) which they called Ming China. The Qing deliberately excluded references and information showing the Jurchens (Manchus) as subservient to the Ming dynasty, from the History of the Ming > to hide his former subservient relationship with the Ming. The True Ming Records were not used to obtain yurchen content during the Ming rule in Ming History because of this.

After the second Manchu invasion of Korea, Joseon Korea was forced to hand over several of its royal princesses as concubines to the Qing Manchu regent, Prince Dorgon. In 1650, Dorgon married the Korean princess Uisun.

This was followed by the creation of the first two Han flags in 1637 (increasing to eight in 1642). Together, these military reforms enabled Hong Taiji to soundly defeat Ming forces in a series of battles from 1640 to 1642 for Songshan and Jinzhou territories. This final victory resulted in the surrender of many of the Ming dynasty's most battle-hardened troops, the death of Yuan Chonghuan at the hands of the Chongzhen Emperor (who thought Yuan had betrayed him), and the complete and permanent withdrawal of the rest. of Ming forces north of the Great Wall.

Meanwhile, Hong Taiji established a rudimentary bureaucratic system based on the Ming model. He established six executive-level boards or ministries in 1631 to oversee finances, personnel, rites, military forces, punishments, and public works. However, these administrative bodies had very little weight initially and it was not until the eve of completing the conquest ten years later that they fulfilled their government functions.

Hong Taiji's bureaucracy numbered many Han Chinese, including many newly handed over Ming officials. Continued Manchu dominance was ensured by an ethnic quota for top bureaucratic appointments. Hong Taiji's reign also saw a fundamental change in policy towards his Han Chinese subjects. Nurhaci had treated the Han in Liaodong differently depending on how much grain they had. Due to a Han revolt in Liaodong in 1623, Nurhaci, who had previously granted concessions to the Han's conquered territories in Liaodong, turned against them and ordered that they should no longer be trusted. He enacted discriminatory policies and assassinations against them, while also ordering that the Han, who assimilated into the Jurchen (in Jilin) before 1619, be treated equally as the Jurchen were, and not as the conquered Han in Liaodong..

Hong Taiji recognized that the Manchus needed to appeal to the Han Chinese, explaining to the reluctant Manchus why he had to treat Ming defector General Hong Chengchou leniently. Hong Taiji inducted them into the 'nation' #3. 4; from yurchen as full (if not first-class) citizens, forced to provide military service. By 1648, less than a sixth of the flag-bearers were of Manchu descent. This policy shift not only increased Hong Taiji's manpower and reduced his military reliance on flags not under his personal control, but also he encouraged other Ming dynasty Chinese subjects to surrender and accept Jurchen rule when they were defeated militarily. Through these and other measures, Hong Taiji was able to centralize power in the office of the Khan, which ultimately prevented the Jurchen federation from splintering after his death.

Demand Heaven's Mandate

Hong Taiji died suddenly in September 1643. As the Jurchen had traditionally "chosen" to its leader through a council of nobles, the Qing state had no clear system of succession. The main contenders for power were Hong Taiji's eldest son Hooge and Hong Taiji's half-brother Dorgon. A compromise installed Hong Taiji's five-year-old son Fulin as the Shunzhi Emperor, with Dorgon as regent and de facto leader of the Manchu nation.

Meanwhile, Ming government officials fought each other, fiscal collapse, and a series of peasant rebellions. They were unable to capitalize on the dispute over the Manchu succession and the presence of a minor as emperor. In April 1644, the capital Beijing was sacked by a coalition of rebel forces led by Li Zicheng, a former minor Ming official, who established a short-lived Shun dynasty. The last Ming ruler, the Chongzhen Emperor, committed suicide when the city fell to rebels, marking the official end of the dynasty.

Next, Li Zicheng led a collection of rebel forces of some 200,000 to confront Wu Sangui, the commanding general of the Ming garrison at Shanhai Pass, a key Great Wall pass fifty miles to the northeast. from Beijing, who defended the capital. Wu Sangui, caught between a rebel army twice his size and an enemy he had fought for years, cast his lot with the strange but familiar Manchus. Wu Sangui may have been influenced by Li Zicheng's mistreatment of wealthy and cultured officials, including Li's own family; it was said that Li took Wu Chen Yuanyuan's concubine for himself. Wu and Dorgon allied to avenge the death of the Chongzhen Emperor. Together, the two former enemies met and defeated Li Zicheng's rebel forces in battle on May 27, 1644.

New Allied armies captured Beijing on June 6. The Shunzhi Emperor was invested as the "Son of Heaven" on October 30. The Manchus, who had positioned themselves as the Ming Emperor's political heirs by defeating Li Zicheng, completed the symbolic transition by holding a formal funeral for the Chongzhen Emperor. However, conquering the rest of China took another seventeen years fighting Ming loyalists, pretenders, and rebels. The last Ming claimant, Prince Gui, sought refuge with the King of Burma, Pindale Min, but was turned over to a Qing expeditionary army commanded by Wu Sangui, who took him back to Yunnan province and executed him in early 1662..

The Qing had shrewdly taken advantage of the Ming civilian government's discrimination against the military and encouraged the Ming military to defect by spreading the message that the Manchus valued their skills. Flags composed of Han Chinese who defected before 1644 they were classified among the Eight Banners, giving them social and legal privileges as well as being acculturated to Manchu traditions. Han defectors so swelled the ranks of the Eight Banners that ethnic Manchus became a minority: only 16% in 1648, with Han banners dominating 75% and Mongol banners doing the rest. Gunpowder weapons such as muskets and artillery were manned by the Chinese banners. Typically, Han Chinese defector troops were deployed as the vanguard, while the Manchu banners acted as reserve or rear-guard forces and were used primarily for quick attacks with maximum impact., in order to minimize losses to ethnic Manchus.

This multi-ethnic force conquered China for the Qing. The three Liaodong officials of the Han banners who played key roles in the conquest of southern China were Shang Kexi, Geng Zhongming, and Kong Youde, who ruled southern China autonomously as viceroys for the Qing after the conquest. Han Chinese banners made up the majority of governors in the early Qing, and they ruled and administered China after the conquest, stabilizing Qing rule. Han banners dominated the post of governor-general at the time of the Shunzhi and Kangxi emperors, and also the post of governor, largely excluding ordinary Han civilians from these posts.

To promote ethnic harmony, a 1648 decree allowed Han Chinese civilian men to marry Banner Manchu women with the permission of the Board of Revenue if they were registered daughters of civil servants or commoners, or with the permission of the captain from their flag company if they were unregistered commoners. Later in the dynasty, policies allowing intermarriage were removed.

The southern cadet branch of the descendants of Confucius who held the title of Wujing boshi (Doctor of the Five Classics) and the 65th generation offspring in the northern branch who held the title of Duke Yansheng had their titles confirmed by the Shunzhi Emperor at the Qing entry into Beijing on October 31. The title of Duke of Kong was retained in subsequent reigns.

The first seven years of the Shunzhi Emperor's reign were dominated by Prince Regent Dorgon. Due to his own political insecurity, Dorgon followed Hong Taiji's example by ruling in the emperor's name at the expense of rival Manchu princes, many of whom he demoted or imprisoned on one pretext or another. Although the period of his regency was relatively short, precedent and Dorgon's example cast a long shadow over the dynasty.

First, the Manchus had entered the "south wall" for Dorgon decisively responded to Wu Sangui's appeal. Then, after capturing Beijing, rather than sack the city as the rebels had done, Dorgon insisted, over the protests of other Manchu princes, on making it the dynastic capital and on reappointing most of the Ming officials. The choice of Beijing as the capital had not been a direct decision, as no major Chinese dynasty had directly taken over the capital from its immediate predecessor. Keeping the Ming capital and bureaucracy intact helped quickly stabilize the regime and hastened the conquest of the rest of the country. Dorgon then dramatically reduced the influence of the eunuchs, a major force in the Ming bureaucracy, and ordered Manchu women not to bind their feet in the Chinese style.

However, not all of Dorgon's policies were equally popular or as easy to implement. The controversial edict of July 1645 (the 'hair-cutting order') forced adult Han Chinese men to shave the front of their heads and comb the remaining hair into the tail hairstyle worn by the Han Chinese. Manchus, on pain of death. The popular description of the order was: "To keep the hair, the head is lost; to keep his head, he cuts his hair". For the Manchus, this policy was a test of loyalty and an aid in distinguishing between friend and foe. For the Han Chinese, however, it was a humiliating reminder of Qing authority that challenged traditional Confucian values. The Classic of Filial Piety (Xiaojing ) held that & # 34; a person's body and hair, which are gifts from his parents, should not be damaged & # 34;. Under the Ming dynasty, adult men did not cut their hair, but instead wore it in the form of a top knot. The order sparked strong resistance to Qing rule in Jiangnan and a massacre of Han Chinese. It was Han Chinese defectors who carried out massacres against people who refused to wear the tail. Li Chengdong, a Han Chinese general who had served the Ming but surrendered to the Qing, ordered his Han troops to carry out three separate massacres in the city of Jiading in one month, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths. By the end of the third massacre, barely one person was left alive in this city. Jiangyin also held out against some 10,000 Qing Han Chinese soldiers for 83 days. When the city wall was finally breached on October 9, 1645, the Qing Han Chinese army led by the Han Ming defector Liu Liangzuo (劉良佐), who was ordered to "fill the city with corpses before sheathing their swords", they massacred the entire population, killing between 74,000 and 100,000 people. The tail was the only aspect of Manchu culture that the Qing forced on the common Han population. The Qing required people serving as officials to wear official Qing clothing, but allowed unofficial Han civilians to continue to wear Hanfu (Han clothing).

The Han Chinese were not opposed to wearing the tail braid on the back of the head, as they traditionally wore all hair long, but they were fiercely opposed to shaving the forehead, so the Qing government focused exclusively on in forcing people to shave their foreheads instead of wearing the braid. Han rebels in the first half of the Qing who opposed the Qing hairstyle wore the braid but defied orders to shave their foreheads. One person was executed for refusing to shave the front, but had voluntarily braided the back of his hair. Only later did Westernized revolutionaries, influenced by Western hairstyles, begin to view the braid as being pulled back and advocated the adoption of short-haired Western hairstyles. The Han rebelled against the Qing as the Taiping even retained their tail braids. on the back, but the symbol of their rebellion against the Qing was the growth of hair on the front of the head, which caused the Qing government to consider shaving the front of the head as the main sign of loyalty to the Qing instead wore the back braid which did not violate Han customs and was not opposed by the Han. Koxinga insulted and criticized the Qing hairstyle, referring to the fly-like shave. Koxinga and his men objected to shave when the Qing demanded that they shave in exchange for recognizing Koxinga as a fiefdom. The Qing demanded that Zheng Jing and his men in Taiwan shave in order to receive recognition as a fiefdom. His men and Prince Ming Zhu Shugui fiercely opposed shaving.

On December 31, 1650, Dorgon died suddenly during a hunting expedition, marking the official start of the Shunzhi Emperor's personal rule. Because the emperor was only 12 years old at the time, most decisions were made on his behalf by his mother, Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang, who turned out to be a skilled political operator.

Though his support had been essential to Shunzhi's rise, Dorgon had centralized enough power in his hands to become a direct threat to the throne. So much so that on his death he was awarded the extraordinary posthumous title of Emperor Yi (in traditional Chinese, 義皇帝), the only instance in Qing history in which a "prince of the blood" Manchu (Traditional Chinese, 親王) was so honored. Two months into Shunzhi's personal rule, however, Dorgon was not only stripped of his titles, but his corpse was dug up and mutilated to atone for multiple "crimes," one of which was hounding to death. to Shunzhi's older brother, Hooge. More importantly, Dorgon's symbolic fall from grace also led to the purge of his family and associates at court, thus returning power to the person of the emperor. After a promising start, Shunzhi's reign was cut short by his untimely death in 1661 at the age of 24 from smallpox. He was succeeded by his third son, Xuanye, who reigned as the Kangxi Emperor.

The Manchus sent Han banners to fight Koxinga Ming loyalists in Fujian. They drove people out of coastal areas to deprive Koxinga Ming loyalists of resources. This led to a misunderstanding that the Manchus were 'afraid of water'. The Han carried out fighting and killing, casting doubt on the claim that fear of water led to coastal evacuation and ban on maritime activities. Although one poem refers to soldiers carrying out massacres in Fujian as & 'Barbarians', both the Green Banner Army and the Han banners were involved and carried out the worst slaughter. 400,000 Green Banner Army soldiers were used against the Three Feudatories in addition to the 200,000 banners.

Kangxi and the Consolidation

The sixty-one-year reign of the Kangxi Emperor was the longest of any Chinese emperor. Kangxi's reign is also celebrated as the beginning of an era known as the "High Qing," during which the dynasty reached the zenith of its social, economic, and military power. Kangxi's long reign began when he was eight years old after the untimely demise of his father. To prevent a repeat of Dorgon's dictatorial monopoly on power during his regency, the Shunzhi Emperor, on his deathbed, hastily appointed four cabinet ministers to rule in his young son's name. The four ministers—Sonin, Ebilun, Suksaha, and Oboi—were chosen for their long service, but also to counteract the influences of others. Most importantly, the four were not closely related to the imperial family and had no claim to the throne. However, as time passed, through chance and machination, Tunesmith, the youngest of the four, achieved such political dominance as to be a potential threat. Although Tunesmith's loyalty was never an issue, his personal arrogance and his political conservatism brought him into increasing conflict with the young emperor. In 1669, Kangxi trickily disarmed and imprisoned Oboi, a significant victory for a fifteen-year-old emperor over a shrewd politician and experienced commander.

Early Manchu rulers established two foundations of legitimacy that help explain the stability of their dynasty. The first was the bureaucratic institutions and neo-Confucian culture they adopted from previous dynasties. The Manchu rulers and the learned official elites of the Han Chinese gradually came to terms. The examination system offered a path for Han Chinese to become civil servants. Imperial patronage of the Kangxi Dictionary demonstrated respect for Confucian learning, while the Holy Edict of 1670 effectively extolled Confucian family values. However, his attempts to discourage Chinese women from binding their feet were unsuccessful.

The second main source of stability was the Central Asian aspect of their Manchu identity, which allowed them to appeal to the Mongol, Tibetan and Uyghur constituents. The forms of Qing legitimization were different for the Chinese, Mongolian, and Tibetan peoples. This contradicted the traditional Chinese worldview that required the acculturation of 'barbarians'. The Qing emperors, by contrast, tried to avoid this with regard to the Mongols and Tibetans. The Qing used the title Emperor (Huangdi) in Chinese, while among the Mongols the Qing monarch was called Bogda kan (wise khan) and Gong Ma in Tibet. The Qianlong Emperor propagated the image of himself as a wise Buddhist ruler, a patron of Tibetan Buddhism. In the Manchu language, the Qing monarch was alternately referred to as Huwangdi (Emperor) or Kan with no special distinction between the two usages. The Kangxi Emperor also welcomed his court Jesuit missionaries, who had first come to China under the Ming. Missionaries, including Tomás Pereira, Martino Martini, Johann Adam Schall von Bell, Ferdinand Verbiest, and Antoine Thomas, held important positions as military weapons experts, mathematicians, cartographers, astronomers, and advisers to the emperor. However, the trust relationship was lost in the later Chinese rites controversy.

Controlling the Mandate of Heaven, however, was a daunting task. The vastness of China's territory meant there were only enough flag troops to garrison key cities that formed the backbone of a defense network that relied heavily on dedicated Ming soldiers. In addition, three surrendered Ming generals were noted for their contributions to the establishment of the Qing dynasty, ennobled as feudal princes (藩王), and given governorships over vast territories in southern China. The head of these was Wu Sangui, who received the provinces of Yunnan and Guizhou, while the generals Shang Kexi and Geng Jingzhong received the provinces of Guangdong and Fujian, respectively.

Over the years, the three feudal lords and their vast territories became increasingly autonomous. Finally, in 1673, Shang Kexi applied to Kangxi for permission to retire to his hometown in Liaodong Province and nominated his son as his successor. The young emperor granted his removal, but denied the inheritance of the manor from him. In reaction, the other two generals decided to request their own retreats to test Kangxi's resolve, thinking that he would not risk offending them. The move failed when the young emperor called his bluff by agreeing to his orders and ordering the three fiefs returned to the crown.

Faced with the stripping of his powers, Wu Sangui, later joined by Geng Zhongming and Shang Kexi's son Shang Zhixin, felt they had no choice but to rebel. The resulting revolt of the three feudatories lasted eight years. Wu ultimately tried in vain to fire the embers of southern China's Ming loyalty by restoring Ming customs, but later declared himself emperor of a new dynasty instead of restoring the Ming. At the peak of the rebels' fortunes, they extended their control as far north as the Yangtze River, almost establishing a divided China. Wu then hesitated to go further north, unable to coordinate strategy with his allies, and Kangxi was able to unify his forces for a counterattack led by a new generation of Manchu generals. By 1681, the Qing government had established control over devastated southern China that took several decades to recover.

Manchu generals and bannermen were initially embarrassed by the better performance of the Han Chinese Green Banner Army. Consequently, Kangxi assigned the generals Sun Sike, Wang Jinbao, and Zhao Liangdong to crush the rebels, as he thought the Han Chinese were superior to the bannermen in fighting other Han people. Similarly, in the northwest of China against Wang Fuchen, the Qing used Green Banner Army soldiers and Han Chinese generals as the main military forces. This choice was due to the rocky terrain, which favored infantry troops over cavalry, a desire to keep banners in reserve, and again, a belief that Han troops were better at fighting other Han people. These Han generals achieved victory over the rebels. Also due to the mountainous terrain, Sichuan and southern Shaanxi were retaken by the Green Banner Army in 1680, with the Manchus involved only in logistics and supplies. 400,000 Army soldiers Green Banner Army and 150,000 Bannermen served on the Qing side during the war. During the revolt, the Qing mobilized 213 Han Chinese Banner companies and 527 Mongolian and Manchu Banner companies. 400,000 Green Banner Army soldiers were used against the Three Feudatories plus 200,000 banners.

The Qing forces were crushed by the Wu from 1673 to 1674. The Qing had the support of most Han Chinese soldiers and the Han elite against the Three Feudatories, as they refused to join Wu Sangui in the revolt, while the Eight Banners and Manchu officers fared poorly against Wu Sangui, so the Qing responded by using a massive army of over 900,000 Han Chinese (non-banners) instead of the Eight Banners, to fight and crush the Three Feudatories. Wu Sangui's forces were crushed by the Army of the Green Banner, made up of defected Ming soldiers.

To extend and consolidate the dynasty's control in Central Asia, the Kangxi Emperor personally led a series of military campaigns against the Dzungars in Outer Mongolia. The Kangxi Emperor was able to successfully drive the invading forces of Galdan Boshugtu Khan (1644-1697) out of these regions, which were later incorporated into the empire. Galdan was eventually assassinated at the start of the Zungaro-Qing Wars (1687-1757), after which China seized control of all of Mongolia, Sinkiang, and Tibet. In 1683, Qing forces received the surrender of Formosa (Taiwan) from Zheng Keshuang, Koxinga's grandson, who had conquered Taiwan from Dutch colonists as a base against the Qing. Zheng Keshuang was bestowed the title of "Duke Haicheng" (海澄公) and he was included in the han banner of the Red Banner of Eight Banners when he moved to Beijing. Several Ming princes had accompanied Koxinga to Taiwan in 1661–1662, including Prince of Ningjing Zhu Shugui and Prince Zhu Honghuan (朱弘桓), son of Zhu Yihai, where they lived in the Kingdom of Tungning. The Qing sent the 17 Ming princes still living in Taiwan in 1683 to mainland China where they spent the rest of their lives in exile, as their lives were spared execution. Winning Taiwan freed Kangxi forces for a series of battles over Albazin, the eastern outpost of the tsarate of Russia. Former Zheng soldiers in Taiwan, such as the rattan shield troops, were also included in the Eight Banners and used by the Qing against the Russian Cossacks at Albazin. The 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk was China's first formal treaty with a European power, and it held the peaceful frontier for the better part of two centuries. After Galdan's death, his followers, like followers of Tibetan Buddhism, tried to control the election of the next Dalai Lama. Kangxi sent two armies to Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, and installed a Dalai Lama who was sympathetic to the Qing.

The Yongzheng and Qianlong Emperors

The reigns of Yongzheng (r. 1723-1735) and his son, the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735-1796), marked the height of the Qing dynasty. During this period, the Qing Empire ruled over 13 million square kilometers of territory. However, as historian Jonathan Spence puts it, the empire at the end of Qianlong's reign was "like the sun at noon." Amid "many glories," he writes, "signs of decline, and even collapse, were becoming evident".

After the Kangxi Emperor's death in the winter of 1722, his fourth son, Prince Yong (雍親王), became the Yongzheng Emperor. In the last years of Kangxi's reign, Yongzheng and his brothers had fought, and there were rumors that he had usurped the throne; most rumors held that Yongzheng's brother Yingzhen (Kangxi's fourteenth son) was the Kangxi Emperor's true successor, and that Yongzheng and his confidante Keduo Long had altered Kangxi's will on the night Kangxi died, although there had been little evidence of these charges. In fact, his father had confided in him sensitive political issues and discussed state policy with him. When Yongzheng came to power at the age of 45, he felt a sense of urgency about the problems that had accumulated in his father's later years, and he did not need instructions on how to wield power. In the words of a recent historian, he was "stern, suspicious and jealous, but extremely capable and resourceful" and, in the words of another, turned out to be an "early modern state-maker of the first order".

Yongzheng acted quickly. First, he promoted Confucian orthodoxy and reversed what he saw as his father's laxity, cracking down on non-orthodox sects and beheading an anti-Manchu writer his father had pardoned. In 1723 he outlawed Christianity and expelled Christian missionaries, although some were allowed to remain in the capital, he then moved to control the government. He expanded his father's palace memorial system, which brought frank and detailed reports on local conditions directly to the throne without being intercepted by bureaucracy, and created a small Grand Council of personal advisers, which eventually became the cabinet de facto of the emperor for the rest of the dynasty. He shrewdly rose to key positions with Manchu and Han Chinese officials who depended on his patronage. As he began to realize that the financial crisis was even greater than he had thought, Yongzheng rejected his father's lenient approach to local landed elites and organized a campaign to enforce the collection of the land tax.. The increased revenue would be used for "money to feed honesty" among local officials and for local irrigation, schools, roads and charities. Although these reforms were effective in the north, in the south, and in the lower Yangzi valley, where Kangxi had courted elites, there were established networks of officials and landlords. Yongzheng sent experienced Manchu commissioners to penetrate the thickets of falsified land records and coded account books, but they were met with trickery, passivity, and even violence. The fiscal crisis persisted.

Yongzheng also inherited diplomatic and strategic problems. An all-Manchu team drafted the Treaty of Kyakhta (1727) to consolidate diplomatic understanding with Russia. In exchange for territory and trading rights, the Qing would have a free hand to deal with the situation in Mongolia. Yongzheng then turned to that situation, where the Dzungars threatened a resurgence, and to the southwest, where local Miao chieftains resisted Qing expansion. These campaigns depleted the treasury but established the emperor's control over military finances.

The Yongzheng Emperor died in 1735. His 24-year-old son, Prince Bao (寶親王), became the Qianlong Emperor. Qianlong personally led military campaigns near Xinjiang and Mongolia, crushing revolts and uprisings in Sichuan and parts of southern China while expanding control over Tibet.

The Qianlong Emperor launched several ambitious cultural projects, including the compilation of Siku Quanshu, or the Complete Repository of the Four Branches of Literature. With a total of more than 3,400 books, 79,000 chapters and 36,304 volumes, the Siku Quanshu is the largest collection of books in Chinese history. However, Qianlong used the Literary Inquisition to silence the opposition. The accusation of the individuals began with the emperor's own interpretation of the true meaning of the corresponding words. If the emperor decided that these were contemptuous or cynical towards the dynasty, he would start the persecution. The literary inquisition began with isolated cases at the time of Shunzhi and Kangxi, but became a pattern under the Qianlong government, during which there were 53 cases of literary persecution.

Underneath foreign prosperity and imperial confidence, the last years of Qianlong's reign were marked by rampant corruption and neglect. Heshen, the emperor's handsome young favorite, took advantage of the emperor's leniency to become one of the most corrupt officials in the dynasty's history. Qianlong's son, the Jiaqing Emperor (r. 1796–1820), eventually forced Heshen to commit suicide.

China also began to suffer from increasing overpopulation during this period. Population growth stagnated during the first half of the 17th century century due to civil wars and epidemics, but prosperity and internal stability gradually reversed this trend. The introduction of new crops from the Americas, such as potatoes and peanuts, also allowed for better food supplies, such that the total population of China during the century XVIII increased from 100 million to 300 million people. All available farmland was soon exhausted, forcing peasants to work ever smaller and more intensively farmed plots. The Qianlong Emperor once lamented the state of the country, commenting, "The population continues to grow, but the land does not." The only remaining part of the empire that had arable farmland was Manchuria, where the provinces of Jilin and Heilongjiang had been walled off as a Manchu homeland. The emperor first decreed that Han Chinese civilians were prohibited from settling. The Qing prohibited Mongols from crossing the borders of their banners, even on other Mongol banners, and from crossing into Neidi (the 18 Han Chinese provinces) and entering he imposed serious punishments on them if they did so to keep the Mongols divided among themselves to benefit the Qing. Mongol pilgrims who wanted to leave their flag borders for religious reasons such as pilgrimage had to apply for passports to give them permission.

Select groups of Han Chinese Bannermen were transferred en masse to Manchu Banners by the Qing, changing their ethnicity from Han Chinese to Manchu. The Han Chinese bannermen of Tai Nikan (台尼堪, Chinese lookout post) and Fusi Nikan (抚顺尼堪, Chinese Fushun) were moved to the Manchu banners in 1740 by order of the Qing Emperor Qianlong. It was between 1618 and 1629. when the Han Chinese of Liaodong, who later became the Fushun Nikan and Tai Nikan, defected to the Jurchen (Manchus). These Manchu clans of Han Chinese origin continue to use their original Han surnames and are marked as Han in origin. the Qing lists of Manchu clans.

Despite officially banning Han Chinese from settling Manchu and Mongol lands, in the 18th century The Qing decided to settle Han refugees from northern China suffering from famine, flood, and drought in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia. The Chinese then reached Manchuria, both illegally and legally, over the Great Wall and Willow Stockade. Because the Manchu landowners wanted the Han Chinese to rent their land and grow grain, most Han Chinese immigrants were not evicted. During the 18th century, the Han Chinese cultivated 500,000 hectares of privately owned land in Manchuria and 203,583 hectares of land that they were part of courier stations, noble estates, and banner lands. In Manchurian garrisons and towns, Han Chinese made up 80% of the population.

In 1796, the White Lotus Society openly rebelled against the Qing government. The White Lotus Rebellion continued for eight years, until 1804, and marked a turning point in the history of the Qing dynasty.

Rebellion, riots and external pressure

At the beginning of the dynasty, the Chinese empire remained the hegemonic power in East Asia. Although there was no formal ministry of foreign affairs, the Lifan Yuan was responsible for relations with the Mongols and Tibetans in Central Asia, while the tax system, a loose set of institutions and customs borrowed from the Ming dynasty, theoretically governed the Relations with the East and Southeast Asian countries. The Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689) stabilized relations with tsarist Russia

The weakening of the Qing dynasty began to show symptoms in the late Qianlong reign and early 19th century century, which expressed itself in the form of internal conflicts and external pressures. Thereafter, the dynasty had to deal with numerous problems, including corruption at all levels of the bureaucracy. The rapid increase in population in the mid-18th century put pressure on the land, causing China to grapple with the problem that the demand for food was greater than the arable land.

In Gansu province, conflicts with Muslims were common during the 18th century and XIX. These conflicts were partly motivated by the characteristics of this province, which until today has a hostile climate and poor communication routes. Although the Han settlers characterized the Muslims as being very united, in reality they used to have constant differences between them and used to concentrate in separate areas. In 1781, Muslim groups split between the Jahriyya Sufis and the Khafiyya Sufis, although both groups were NaqshbandiSufi suborders. This conflict led to a Muslim rebellion known as the Jahriyya revolt. The Qing dynasty in China crushed this revolt with the help of Khafiyya Sufi Muslims.

In 1814, the Eight Trigrams uprising broke out in Zhili, Shandong, and Henan provinces, initiated by the Tianli sect, an offshoot of the White Lotus Sect.[citation needed]

In addition to the internal problems facing the Qing dynasty, external pressures were added with the expansion of European empires from the 18th century . Colonial maritime powers gradually expanded throughout the world, as European states developed economies based on maritime trade. The dynasty was faced with newly developed concepts of the international system and state-to-state relations. European trading posts expanded to territorial control in nearby India and on the islands that are now Indonesia. The Qing response, successful for a time, was to establish the Canton System in 1756, which restricted maritime trade to that city (modern-day Guangzhou) and granted monopoly trading rights to private Chinese merchants. The British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company had received similar monopoly rights from their governments.

In 1793, the British East India Company, with the support of the British government, sent a delegation to China under Lord George Macartney to open up free trade and establish relations on an equal footing. The imperial court saw trade as a secondary interest, while the British saw maritime trade as the key to their economy. The Qianlong Emperor told Macartney "the kings of the myriad nations come by land and sea with all manner of precious things" and "consequently there is nothing that we lack".

Demand in Europe for Chinese products such as silk, tea and ceramics could only be met if European companies channeled their limited supplies of silver to China. In the late 1700s, the governments of Great Britain and France were deeply concerned about the imbalance of trade and the drain on silver. To meet the growing Chinese demand for opium, the British East India Company greatly expanded its production in Bengal. Since China's economy was essentially self-sufficient, the country had little need to import goods or raw materials from Europeans, so the usual form of payment was through silver. The Daoguang Emperor, concerned both about the flow of silver and the damage opium smoking was causing his subjects, ordered Lin Zexu to end the opium trade. Lin confiscated the opium stocks without compensation in 1839, prompting Britain to send a military expedition the following year.

The First Opium War revealed the antiquated state of the Chinese military. The Qing navy, made up entirely of wooden sailing junks, was severely outmatched by the modern tactics and firepower of the British Royal Navy. British soldiers, using advanced muskets and artillery, easily outmatched and outmatched the Qing forces in land battles. The surrender of the Qing in 1842 marked a decisive and humiliating blow to China. The Treaty of Nanjing, the first of the "unequal treaties," demanded war reparations, forced China to open the Treaty Ports of Canton, Amoy, Fuchow, Ningpo, and Shanghai to Western trade and missionaries, and cede Hong Kong Island to Great Britain. It revealed weaknesses in the Qing government and sparked rebellions against the regime. In 1842, the Qing dynasty waged war with the Sikh Kingdom (India's last independent kingdom), resulting in a negotiated peace and a return to the status quo ante bellum.

The Taiping Rebellion in the mid-19th century was the first major instance of anti-Manchu sentiment. Amid widespread social unrest and worsening famine, the rebellion not only posed the gravest threat to the Qing rulers, it has also been called the "bloodiest civil war of all time"; during its fourteen-year course between 1850 and 1864, between 20 and 30 million people died. Hong Xiuquan, an unsuccessful civil service candidate, in 1851 launched an uprising in Guizhou Province and established the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom with his own Hong as king Hong announced that he had visions from God and that he was the brother of Jesus Christ. Slavery, concubinage, arranged marriage, opium use, foot binding, judicial torture, and idol worship were prohibited. However, success led to infighting, defections, and corruption. In addition, British and French troops, equipped with modern weapons, had come to the aid of the Qing imperial army. It was not until 1864 that the Qing armies under Zeng Guofan managed to crush the revolt. After the outbreak of this rebellion, there were also revolts by Chinese Muslims and Miao against the Qing dynasty, notably the Miao Rebellion (1854-1873) in Guizhou, the Panthay Rebellion (1856-1873) in Yunnan, and the of the Dungans (1862-1877) in the north-west.

Western powers, largely dissatisfied with the Treaty of Nanjing, lent grudging support to the Qing government during the Taiping and Nian rebellions. China's income fell sharply during the wars as vast areas of farmland were destroyed, millions of lives were lost, and countless armies were raised and equipped to fight the rebels. In 1854 Britain attempted to renegotiate the Treaty of Nanking, inserting clauses allowing British commercial access to Chinese rivers and the creation of a permanent British embassy in Beijing.

In 1856, Qing authorities, searching for a pirate, boarded a ship, the Arrow, which the British claimed had been flying the British flag, an incident that led to World War II. of Opium. In 1858, with no other choice, the Xianfeng Emperor agreed to the Treaty of Tientsin, which contained clauses deeply insulting to the Chinese, such as a requirement that all official Chinese documents be written in English and a condition granting warships British unlimited access to all Chinese navigable rivers.

The ratification of the treaty the following year led to a resumption of hostilities. In 1860, with Anglo-French forces marching on Beijing, the emperor and his court fled the capital for the imperial hunting lodge at Rehe. Once in Beijing, Anglo-French forces looted the Old Summer Palace and, in an act of revenge for the arrest of several Englishmen, burned it down. Prince Gong, a younger half-brother of the emperor, who had been left as his brother's proxy in the capital, was forced to sign the Beijing Convention. The humiliated emperor died the following year at Rehe.

Strengthening and frustrating reforms

However, the dynasty recovered. Chinese generals and officials such as Zuo Zongtang led the suppression of the rebellions and got behind the Manchus. When the Tongzhi Emperor came to the throne at the age of five in 1861, these officials rallied around him in what was called the Tongzhi Restoration. His goal was to adopt Western military technology to preserve Confucian values. Zeng Guofan, in alliance with Prince Gong, sponsored the rise of younger officials such as Li Hongzhang, who put the dynasty back on its feet financially and instituted the Self-Empowerment Movement. The reformers then proceeded with institutional reforms, including China's first unified ministry of foreign affairs, the Zongli Yamen; allow foreign diplomats to reside in the capital; establishment of the Imperial Maritime Customs Service; the formation of modernized armies, such as the Beiyang army, as well as a navy; and the purchase of armament factories from the Europeans.

The dynasty gradually lost control of outlying territories. In exchange for promises of support against the British and French, the Russian Empire seized large tracts of territory in the northeast in 1860. The period of cooperation between the reformers and the European powers ended with the Tientsin Massacre of 1870, which was incited by the murder of French nuns provoked by the belligerence of local French diplomats. Beginning with the Cochinchina War in 1858, France expanded control of Indochina. By 1883, France was in full control of the region and had reached the Chinese border. The Sino-French War began with a surprise attack by the French against the South China fleet at Fuzhou. After that, the Chinese declared war on the French. A French invasion of Taiwan was stopped, and the French were defeated ashore at Tonkin at the Battle of Bang Bo. However, Japan threatened to enter the war against China because of the Gapsin Coup and China decided to end the war with negotiations. The war ended in 1885 with the Treaty of Tientsin (1885) and Chinese recognition of the French protectorate in Vietnam.

In 1884, pro-Japanese Koreans in Seoul led the Gapsin Coup. Tensions between China and Japan rose after China intervened to suppress the uprising. Japanese Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi and Li Hongzhang signed the Convention of Tientsin, an agreement to withdraw troops simultaneously, but the First Sino-Japanese War of 1895 was a military humiliation. The Treaty of Shimonoseki recognized the independence of Korea and ceded Taiwan and Pescadores to Japan. The terms could have been harsher, but when a Japanese citizen attacked and injured Li Hongzhang, an international outcry shamed the Japanese into checking them out. The original agreement stipulated the cession of the Liaodong Peninsula to Japan, but Russia, with its own designs on the territory, along with Germany and France, in the Triple Intervention, successfully pressured the Japanese to abandon the peninsula.

These years saw an evolution in Empress Dowager Cixi's (Wade–Giles: Tz'u-Hsi) involvement in state affairs. She entered the imperial palace in the 1850s as a concubine of the Xianfeng Emperor (r. 1850-1861) and came to power in 1861 after her five-year-old son, the Tongzhi Emperor ascended the throne. She, Empress Dowager Ci'an (who had been the Empress of Xianfeng) and Prince Gong (son of the Daoguang Emperor), staged a coup that overthrew several regents for the boy emperor. Between 1861 and 1873, she and Ci'an served as regents, choosing the regnal title "Tongzhi" (ruling together). After the emperor's death in 1875, Cixi's nephew the Guangxu Emperor seized the throne, in violation of the dynastic custom of the new emperor being of the next generation, and began another regency. In the spring of 1881, Ci'an died suddenly, aged just forty-three, leaving Cixi as sole regent.

From 1889, when Guangxu began to rule in its own right, until 1898, the empress dowager lived in semi-retirement, spending most of the year in the Summer Palace. On November 1, 1897, two German Catholic missionaries were assassinated in the southern part of Shandong province (the Juye incident). Germany used the killings as a pretext for a naval occupation of Jiaozhou Bay. The occupation provoked a "struggle for concessions" in 1898, which included the German lease of Jiazhou Bay, the Russian takeover of Liaodong, and the British lease of the New Territories of Hong Kong.

In the wake of these external defeats, the Guangxu Emperor initiated the Hundred Days' Reform of 1898. Newer and more radical advisers such as Kang Youwei were given positions of influence. The emperor issued a series of edicts, and plans were made to reorganize the bureaucracy, restructure the school system, and appoint new officials. The opposition from the bureaucracy was immediate and intense. Although she had been involved in the initial reforms, the Empress Dowager intervened to suspend them, arresting and executing several reformers and assuming day-to-day control of politics. However, many of the plans were kept in place and the objectives of the reform were implemented.

Widespread drought in North China, combined with the imperialist designs of the European powers and the instability of the Qing government, created conditions that led to the rise of the Straight and Harmonious Fists, or "Boxers." In 1900, local groups of Boxers proclaiming their support for the Qing dynasty murdered foreign missionaries and large numbers of Chinese Christians, then gathered in Beijing to lay siege to the Branch Quarter, starting the Boxer Rebellion. A coalition of European, Japanese, and Russian armies (the Eight-Nation Alliance) entered China without prior diplomatic notice, let alone permission. Cixi declared war on all of these nations, only to lose control of Beijing after a short but hard-fought campaign. Cixi fled to Xi'an. The victorious allies drew up dozens of demands on the Qing government, including compensation for its expenses in the invasion of China and the execution of complicit officials.

Decline, Puyi, revolution and end of Imperial China

At the beginning of the 20th century, mass civil disorder had begun in China and was steadily growing. To overcome such problems, Empress Dowager Cixi issued an imperial edict in 1901 calling for reform proposals from the Governor-Generals and Governors and ushered in the era of the dynasty's "New Policies", also known as the "Late Reform of Qing». The edict paved the way for the most far-reaching reforms in terms of their social consequences, including the creation of a national education system and the abolition of the imperial examinations in 1905.

The Guangxu Emperor died on November 14, 1908, and Cixi died the next day. It was rumored that either she or Yuan Shikai ordered trusted eunuchs to poison the Guangxu Emperor, and an autopsy carried out nearly a century later confirmed the lethal levels of arsenic in his corpse. Puyi, the eldest son of Zaifeng, Prince Chun and nephew of the Childless Guangxu Emperor, he was appointed successor at the age of two, leaving Zaifeng with the regency. This was followed by the removal of General Yuan Shikai from his former positions of power.

In April 1911, Zaifeng created a cabinet that included two deputy prime ministers. However, this cabinet was also known by contemporaries as "The Royal Cabinet" because among the thirteen members of the cabinet, five were members of the imperial family or relatives of Aisin Gioro. This brought a wide range of negative opinions from senior officials. like Zhang Zhidong. The Wuchang uprising of October 10, 1911 was a success that led to the Xinhai Revolution; by November 14, all 15 provinces had rejected Qing rule. This led to the creation of a new central government, the ROC, in Nanjing with Sun Yat-sen as its provisional head. Many provinces soon began to "break away" of Qing control. Seeing a hopeless situation, the Qing government brought Yuan Shikai back to military power. He seized control of his Beiyang army to crush the revolution in Wuhan at the Battle of Yangxia. After taking over as prime minister and creating his own cabinet, Yuan Shikai went so far as to call for Zaifeng's removal from the regency. This removal then followed with Empress Dowager Longyu's instructions. Yuan Shikai was now a dictator: the ruler of China and the Manchu dynasty had lost all power; he formally abdicated in early 1912.

Premier Yuan Shikai and his Beiyang commanders decided that going to war would be unreasonable and costly. Similarly, Sun Yat-sen wanted a republican constitutional reform, for the benefit of China's economy and people. With Empress Dowager Longyu's permission, Yuan Shikai began negotiations with Sun Yat-sen, who decided that his goal had been achieved by forming a republic and that he could therefore allow Yuan to take over as president of the republic. Republic of China.

On February 12, 1912, after rounds of negotiations, Longyu issued an imperial edict that caused the boy emperor Puyi to abdicate. This ended over 2,000 years of Imperial China and began a prolonged period of instability from warlord factionalism. Disorganized political and economic systems combined with widespread criticism of Chinese culture led to questions and doubts about the future. Some Qing supporters organized as the Royalist Party and tried to use militant activism and outright rebellion to restore the monarchy, but to no avail. In July 1917, there was an unsuccessful attempt to restore the Qing dynasty led by Zhang Xun, which was quickly reversed by the republican troops. In the 1930s, the Empire of Japan invaded Northeast China and founded Manchukuo in 1932, with Puyi as its emperor. After the Soviet Union invaded, Manchukuo fell in 1945.

Government

The early Qing emperors adopted the bureaucratic structures and institutions of the previous Ming dynasty, but divided rule between the Han Chinese and the Manchus, with some positions also given to the Mongols. Like earlier dynasties, the Qing they recruited officials through the imperial examination system, until the system was abolished in 1905. The Qing divided positions into civilian and military positions, each with nine grades or ranks, each subdivided into "a" and "b" categories..

Civilian appointments ranged from assistant to the emperor or Grand Secretary in the Forbidden City (highest) to prefectural tax collector, jail warden, deputy police commissioner, or tax examiner. Military appointments ranged from being a Field Marshal or Chamberlain of the Imperial Bodyguard to Sergeant Third Class, Corporal, or Private First or Second Class.

Central government agencies

The formal structure of the Qing government centered on the Emperor as the absolute ruler, who presided over six Boards (Ministries), each headed by two presidents and assisted by four vice presidents. In contrast to the Ming system, however, Qing ethnic policy dictated that appointments be divided between Manchu nobles and Han officials who had passed the highest levels of state examinations. The Grand Secretariat, which had been an important policy-making body under the Ming, lost its importance during the Qing dynasty and became an imperial chancellery. Institutions that had been inherited from the Ming formed the core of the Qing Outer Court, which handled routine matters and was located in the southern part of the Forbidden City.

In order not to let routine administration take over the governance of the empire, the Qing emperors ensured that all important matters were decided in the Inner Court, which was dominated by the imperial family and Manchu nobility and which It was located in the northern part of the Forbidden City. The central institution of the inner court was the Grand Council. It arose in the 1720s under the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor as a body tasked with managing the Qing military campaigns against the Mongols, but it soon took over other military and administrative tasks and served to centralize authority under the crown. Councilors served as a kind of private council for the emperor.

The six ministries and their respective areas of responsibility were as follows:

Civilian Appointments Board

- The administration of staff of all civil servants, including assessment, promotion and dismissal. He was also in charge of the "list of honors".

Board of Revenues

- The literal translation of the Chinese word Hu. (index) is "home". For much of Qing's history, the government's main source of revenue came from land ownership taxes supplemented by official monopolies on salt, which was an essential element of the home, and tea. Thus, in the predominantly agrarian Qing dynasty, the “home” was the basis of imperial finance. The department was responsible for revenue collection and government financial management.

Board of Rites

- This board was responsible for all matters related to the court protocol. It organized the periodic cult of the ancestors and several gods by the emperor, managed relations with the tax nations and supervised the national civil examination system.

War Board

- Unlike its predecessor Ming, who had total control over all military matters, the Qing War Board had very limited powers. First, the eight flags were under the direct control of the emperor and the hereditary princes Manchus and Mongols, leaving the ministry only with authority over the Army of the green banner. Moreover, the functions of the ministry were purely administrative. The campaigns and movements of troops were monitored and led by the emperor, first through the Manchu ruling council and then through the Great Council.

Board of Punishments

- The Board of Punishment handled all legal matters, including the supervision of several courts of justice and prisons. Qing's legal framework was relatively weak compared to today's legal systems, as there was no separation from the executive and legislative branches of government. The legal system could be inconsistent and sometimes arbitrary, because the emperor governed by decree and had the last word in all judicial results. The emperors could (and did) revoke the trials of the lower courts from time to time. The impartiality of treatment was also a problem under the control system practiced by the Manchu government over most Chinese have. To counter these deficiencies and keep the population online, the Qing government maintained a very harsh penal code for the population have, but it was no more severe than previous Chinese dynasties.

Works Board

- The Labor Board managed all government construction projects, including palaces, temples and waterways repair and flood canals. He was also in charge of coins.

Since the early Qing, the central government was characterized by a dual appointment system whereby each position in the central government had one Manchu and one Han Chinese assigned to it. The Han Chinese appointee was required to do the substantive work and the Manchus to ensure Han loyalty to the Qing government.

In addition to the six boards, there was an exclusive Lifan Yuan of the Qing government. This institution was established to oversee the administration of Tibet and the Mongolian lands. As the empire expanded, it took administrative responsibility for all ethnic minority groups living in and around the empire, including early contacts with Russia, then considered a tributary nation. The office had the status of a full ministry and was headed by officials of equal rank. However, the appointees were at first restricted to ethnic Manchu and Mongolian candidates only, until they were later opened to Han Chinese as well.

Although the Board of Rites and Lifan Yuan performed some tasks of an overseas office, they did not become a professional foreign service. It was not until 1861, a year after losing the Second Opium War to the Anglo-French coalition, that the Qing government bowed to foreign pressure and created a proper foreign affairs office known as the Zongli Yamen. Originally, the office was intended to be temporary, and was staffed by seconded officials from the Grand Council. However, as dealings with foreigners became increasingly complicated and frequent, the office grew in size and importance, aided by revenue from customs duties under its direct jurisdiction.

There was also another government institution called the Imperial Household Department, which was unique to the Qing dynasty. It was established before the fall of the Ming, but matured only after 1661, after the death of the Shunzhi Emperor and the accession of his son, the Kangxi Emperor. The department's original purpose was to manage the internal affairs of the imperial family and the inner palace activities (in whose tasks he largely replaced eunuchs), but also played an important role in Qing relations with Tibet and Mongolia, in commercial activities. (jade, ginseng, salt, furs, etc.), ran textile factories in the Jiangnan region, and even published books. Relationships with salt Superintendents and salt merchants, such as those in Yangzhou, were particularly lucrative, especially because they were direct and did not go through absorbing layers of bureaucracy. The department was manned by booi, or "bond servants", of the Upper Three Banners. By the 19th century, managed the activities of at least 56 sub-agencies.

Administrative division

Qing China reached its greatest extent during the 18th century, when it ruled China proper (eighteen provinces), thus such as the areas of present-day Northeast China, Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Tibet, with an approximate size of 13 million km². Originally there were 18 provinces, all of them in China proper, but later this number was increased to 22, with Manchuria and Xinjiang divided or made provinces. Taiwan, originally part of Fujian Province, became its own province in the 19th century, but was ceded to the Empire of Japan after the First Sino-Japanese War at the turn of the century. In addition, many neighboring countries, such as Korea (Joseon dynasty) or Vietnam frequently paid homage to China during much of this period. The Katoor dynasty of Afghanistan also paid homage to the Qing dynasty of China until the mid-19th century. During the Qing dynasty, the Chinese claimed sovereignty over the Taghdumbash Pamirs in southwestern Tajik Autonomous County of Tashkurgan but allowed the Mir of Hunza to administer the region in exchange for tribute. Until 1937 the inhabitants paid homage to the Mir of Hunza, who exercised control over the pastures. The Kokand Khanate was forced to present itself as a protectorate and pay homage to the Qing dynasty in China between 1774 and 1798.

- North and South Circuits of Tian Shan (later became the province of Xinjiang): sometimes the small and semi-autonomous Kanatos Kumul and Turfan are placed in an "Eastern Circle".

- Mongolia Exterior – Khalkha, Hovd, Hövsgöl, Tannu Urianha.

- Mongolia Interior – 6 leagues (Jirim, Josotu, Juu Uda, Shilingol, Ulaan Chab, Ihe Juu)

- Other Mongolian leagues – Alshaa khoshuu, Ejine khoshuu, Ili khoshuu (in Xinjiang), Köke Nuur; directly governed areas: Dariganga (special region designated as the Emperor's pasture), Guihua Tümed, Chakhar, Hulunbuir.

- Tibet (Ü-Tsang and western Kham, approximately the surface of the present Tibetan autonomous region)

- Manchuria (North of China, then became provinces)

- Eighteen provinces (China)

- Additional provinces at the end of Qing dynasty

Territorial administration

The Qing organization of provinces was based on the fifteen administrative units established by the Ming dynasty, which later became eighteen provinces by dividing, for example, Huguang into Hubei and Hunan provinces. The provincial bureaucracy continued the Yuan and Ming practice of three parallel lines, civil, military, and censorship or surveillance. Each province was administered by a governor (巡撫, xunfu) and a provincial military commander (提督, tidu). Below the province were prefectures (府, fu) operating under a prefect (知府, zhīfǔ), followed by sub-prefectures under a sub-prefect. The lowest unit was the county, supervised by a county magistrate. The eighteen provinces are also known as "proper China." The position of viceroy or governor-general (總督, zongdu) was the highest rank in the provincial administration. There were eight regional viceroys in China proper, each usually taking charge of two or three provinces. The Viceroy of Zhili, who is responsible for the area around the capital, Beijing, is often considered the most honorable and powerful viceroy among the eight.

- Virrey de Zhili – by Zhili

- Virrey of Shaan-Gan – by Shaanxi and Gansu

- Virrey de Liangjiang – by Jiangsu, Jiangxi and Anhui

- Virrey de Huguang – by Hubei and Hunan

- Virrey de Sichuan – by Sichuan

- Virrey de Min-Zhe – by Fujian, Taiwan and Zhejiang

- Virrey de Liangguang – by Guangdong and Guangxi

- Virrey de Yun-Gui – by Yunnan and Guizhou

By the middle of the 18th century, the Qing had brought outer regions such as Inner and Outer Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang. Imperial commissioners and garrisons were sent to Mongolia and Tibet to oversee their affairs. These territories were also under the supervision of a central government institution called the Lifan Yuan. Qinghai was also placed under the direct control of the Qing court. Xinjiang, also known as Chinese Turkestan, was subdivided into the northern and southern regions of the Tian Shan Mountains, also known today as Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin respectively, but the post of Ili General was established in 1762 to exercise military jurisdiction. and unified administrative authority over both regions Dzungaria was fully opened to Han migration by the Qianlong Emperor from the very beginning. Han migrants were initially prohibited from settling permanently in the Tarim Basin, but the ban was lifted after Jahangir Khoja's invasion in the 1820s. Similarly, Manchuria was also ruled by military generals until its division. in provinces, although some areas of Xinjiang and northeast China were lost to the Russian Empire in the mid-19th century. Manchuria was originally separated from China proper by the interior of the Willow Palisade, a ditch and embankment planted with willow trees intended to restrict Han Chinese movement, as the area was off limits to Han Chinese civilians until the government began to colonize the area, especially from the 1860s. (Elliott, 2000)