Pyrenees

The Pyrenees or the Pyrenees is a mountain system located in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula, which forms the natural border between Andorra, Spain and France. It extends in an east-west direction along 491 km approximately, from Cape Creus in the Mediterranean Sea to its junction with the Cantabrian Mountains, where it has established the Pamplona fault as its conventional geological limit, there being no geographical interruption between both formations. In its central part it is about 150 km wide.

On the northern slope, the Pyrenees stretch across the French regions of New Aquitaine and Occitania. On the southern slope by the Spanish autonomous communities of the Basque Country, Navarra, Aragon and Catalonia. The micro-State of Andorra is nestled in the mountains.

These mountains are home to peaks over 3,000 meters above sea level, such as Aneto (3,404 m), Posets (3,375 m), Monte Perdido (3,355 m), Pico Maldito (3,350 m), Pico Espadas (3,332 m), the Vignemale (3,298 m), the Balaitus (3,144 m) and the Pica d'Estats (3,143 m), small glaciers, lakes and cirques of glacial origin, and numerous valleys and canyons.

Toponymy

Called in Spanish the «Pyrenees», they are also referred to as the «Pyrenees», which would be what their inhabitants would prefer to call when referring to a part or region of these. In other languages of the area there are various endotoponyms to name this mountain range: "Pyrénées" in French, "Pirineus" or "Pirineu" in Catalan, "Pirenèus" in Occitan, "Pireneus" or "Perinés" in Aragonese and "Pirinioak", "Bortuak" or "Auñamendiak" in Basque.

In ordinary language, the word «Pyrenees» is applied to the set of high Spanish-French border mountain ranges. The expression "Central Pyrenees" is used to refer to the geographical area of the Pyrenees mountain range that extends approximately, according to different works, between the peaks of Somport, in the western part, and the Maladeta massif, in the eastern part.

Etymology

The word Pyrenees comes from the mythological daughter of Bébrice, Pirene. According to the Greeks, the Pyrenees were named after her from Pirene, a young woman from the region that Hercules took with him on one of her journeys and when she died, she accumulated stones to seal her grave.

The Small Dictionary of Basque and Pyrenean Mythology by Olivier de Marliave (Alejandría Ed.), states the following:

Pyrene: The daughter of Bébrix, legendary king of the Sardinian, would be at the origin of the mountain range of the Pyrenees. Pirene was seduced by Hercules, who went through the Sardinian to do his tenth work. The half-god abandoned the girl, who, despite everything, wanted to follow her in love. But she was attacked and eaten by wild animals. Hercules, alerted by the screams of Pirene, returned on his steps, but found no more than a lifeless body. As a tribute to this proof of love, Hercules returned her home and built an immense mausoleum by tuning up to the infinite rocks that formed a series of mountains, to which Pyrenees called. The people of Ariege place the tomb of Pirene in the cave of Lombrives (Ussat), where concretions of stalagmites form a sort of colossal tomb.Small Dictionary of Basque and Pirenaica Mythology de Olivier de Marliave

According to another legend, Pirene gave birth to a snake before she died, and her body was placed on a bonfire. The incineration fire spread to the mountain, to the point that the towns of Ampurdán where Greek merchants lived called the Pyrenees (from the Greek pyr, pyros, 'fire'). ') to those massifs covered in flames.

Another version says that it is an ancestral place-name, of Iberian or Basque origin. According to this language, the mountain range was named Ilene os, which means "mountains of the Moon", since Ilene is the Moon.[citation needed ]

Another of the most accepted theories is that the name comes from a fire (fire in Greek is pyros) reported by Strabo and Diodorus Siculus, caused by some shepherds plowing their land of crops. It was said that even the gold and silver veins were smelted at the subsoil level.

Geography

The Pyrenees form a rectilinear chain with a total length of 430 kilometers from the Mediterranean (Cap of Creus) to the Cantabrian (Jaizkibel). The western limit can be arbitrary since the Pyrenees gradually merge with the Basque Mountains, which in turn have their continuity in the Cantabrian mountain range (the Pyrenean-Cantabrian axis reaches 1000 km of mountainous continuity). The simplest geographical definition of the Pyrenees is its character as an isthmus between the Mediterranean and the closest point in the Bay of Biscay, continuing further in the Basque-Cantabrian chain.

The main elevations are in its central part, although slightly unbalanced towards the east, the side towards which it descends more sharply (still 50 km from the Mediterranean coast rises the Canigó, with 2785 m of altitude). Towards this same side there are cuts in the trenches of the Segre and Tet rivers. To the west, the axis of the mountain range descends gently to link up with the moderate-altitude mountain ranges of the Basque Country, although with more abrupt erosions. The maximum width of the mountain range is 150 km in its central part, of which one third It corresponds to the northern sector, primarily French, where the peaks have a more abrupt descent, and two thirds belong to the southern area. This width is also reduced at the extremes: it reaches between 25 and 30 km on the Navarrese side and about 10 on the Catalan side.

In the structure of the mountain range, the axial Pyrenees can be distinguished, which is the fundamental nucleus of the mountain system and supposes a directrix axis of the same. It extends longitudinally through a band of Paleozoic materials, remains of an ancient Hercynian massif that has disappeared. Its highest peak is the Aneto peak (3,404 m) and the Canigó (2,765 m) and Posets (3,375 m) peaks stand out, among many others.

The second constitutive element is the pre-Pyrenees, which is attached to the flanks of the axial Pyrenees. It is made up of several lines of mountains with a more modern geological structure. Its peaks frequently exceed 2,000 meters of altitude.

In its southern part, it is broken down into two: interior and exterior mountain ranges (the peaks of Leyre (1,371 m), Loarre (1,864 m), Pic de Guara (2,077 m) and Montsec (1,693 m) stand out.), which are separated by a longitudinal depression, called the Middle Pre-Pyrenees Depression (Pamplona basin, the Berdún channel and the Tremp basin). The mountains and valleys of this area are characterized by having lower altitudes than those of the central sector, since few peaks in the Pre-Pyrenees exceed 2,000 meters of altitude.

On the northern slope, the Pyrenees span the French departments of Pyrénées-Atlantiques (New Aquitaine), Hautes-Pyrénées, Haute-Garonne, Ariège and Pyrénées-Orientales (Occitania). On the southern slope, the Pyrenees are included in the Spanish provinces of Guipúzcoa (Basque Country), Navarra, Huesca and Zaragoza (Aragon), Lérida and Gerona (Catalonia). The small country of Andorra is located in the mountains.

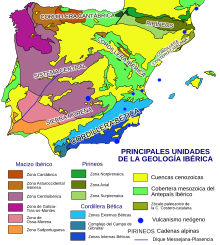

Geology

The Pyrenees are older than the Alps: their sediments were first deposited in coastal basins during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras. Between 100 and 150 million years ago, during the Early Cretaceous period, the Bay of Biscay unfurled, pushing present-day Spain against France and applying intense compressive pressure to large layers of sedimentary rock. The intense pressure and uplift of the earth's crust first affected the eastern part and moved progressively to the entire chain, culminating in the Eocene Epoch.

The eastern part of the Pyrenees consists mainly of granite rocks and gneiss, while in the western part the granite peaks are flanked by layers of limestone. The massive and unused character of the range comes from its abundance of granite, which is particularly resistant to erosion as well as weak glacial development.

The upper parts of the Pyrenees contain low-relief surfaces that form a peneplain. This peneplain originated no earlier than in Late Miocene times. Presumably formed aloft as extensive sedimentation raised the local base level considerably.

The most pronounced geological characteristics are the asymmetry of the slopes in the transverse direction and also in the longitudinal direction; that is to say, its slope is much more accentuated on the French slope than on the Spanish one, and it descends gently towards the west and more abruptly towards the east.

Formed during the Cenozoic Era on the occasion of the great Alpine-Himalayan folding, from a structural point of view the Pyrenees are clearly different from the Alps, since while the landslide sheets play a decisive role in these, the Pyrenees can be classified as together as an autochthonous folding mountain range.

Glaciers

Because the glaciation of the Quaternary Era affected the Pyrenees more decisively than the other Spanish mountain ranges, there are traces of glacial modeling from the Canigó to the Adi peak. Most of the current lakes are of glacial origin. Today the Pyrenees only have cirque glaciers or glaciers with small tongues above 2,700 meters: Aneto, Balaitus, Vignemale, Monte Perdido and Maladeta on the Spanish side and Ossue or Troumouse on the French side.

Spikes

According to the work of Juan Buyse, accepted as an official list by the International Union of Mountaineering Associations (UIAA), 11 zones are established in the Pyrenees mountain range that correspond to the large massifs where the 212 three thousand are distributed, that is, the peaks that exceed 3000 altitude above sea level. Of these summits, 129 are considered major and 83 are secondary.

Rivers

This mountain range is the cradle of important rivers:

- On the French side, the rivers Adur, Garona, Levelle, Tec, Têt, Aglí and Aude.

- On the Spanish side, the rivers Bidasoa, Aragon-Subordán, Aragon, Gállego, Ara, Cinca, Ésera, Isábena, Noguera Ribagorzana, Noguera Pallaresa, Valira, Segre, Ter, Llobregat, Muga and Fluviá.

Flora and fauna

Flora

The flora of the Pyrenees includes around 4,500 species, of which 160 are endemic, such as the king's crown (Saxifraga longifolia), the Pyrenean columbine (Aquilegia pyrenaica) and white thistle (Eryngium bourgatii). As for the trees, the black pine (Pinus uncinata) and the Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) stand out at high altitude (subalpine level), the beech ( Fagus sylvatica) and common fir (Abies alba) at mid-mountain level. Holm oaks, oaks and chestnut trees grow at low level and in the foothills.

The Mediterranean influence makes the eastern and southern Pyrenees, sunnier, have a different floristic composition from the rest of the mountain range. The west-east orientation of the mountain system means that a large number of species that were present in the north of this region during the Tertiary era have disappeared due to the cold of the last great ice age.

The climate determines the flora of the Pyrenees. In the Atlantic Pyrenees, that is to say the north and the extreme west, there are green meadows alternating with oak forests in the valley and at the foot of the mountains, and beech and pine forests in the middle of the mountains. The upper limit of the mountain is located between 2,000 and 2,500 m (pines), being relieved by subalpine moors (erica, rhododendron) above 2,500 to 3,000 m, as there are only stones and small glaciers. The Irati forest (in the north of Navarra) should be highlighted, considered the largest beech forest in Europe and the largest forest mass in the Pyrenees.

The mid-mountain on the southern slope, the driest, has typical Mediterranean vegetation: garrigue, green beech forests, black pines and Scots pines. The highest valleys stand out for their meadows, beech, fir and Scots pines. In the highest part there would not be much difference with that of the northern slope, were it not for the predominance of limestone soils that prevail over the climate and lower the vegetal limit. In the extreme east, the torrential rains of the Mediterranean, combined with the summer drought, give rise to large beech and holm oak groves.

The icon par excellence of the Pyrenean flora has always been the Edelweiss or snow flower, which we find in the Aragonese limestone Pyrenees such as the Añisclo and Pineta canyon, or in the highlands of the Ordesa valley, and which is protected in Spain. It is very rare in the Catalan Pyrenees.

Wildlife

The Pyrenees is a unique place for the contemplation of several animal species due to the steepness of the terrain, which until now has prevented human overcrowding, a factor that poses a danger to biodiversity despite the bureaucratic problems for its correct management through through centuries. Among the almost 200 animal species that survive in the mountain range, the presence of the mythical brown bear (Ursus arctos arctos) stands out above all, which, even persecuted and fleeced, seems to recover very slowly from its decline. In 2019, a population of 52 specimens was estimated.

Among mammals, the chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica) stands out, which went from being on the brink of extinction at the beginning of the century XIX, up to the current 45,000 specimens, a story equally repeated in the case of the deer or the roe deer, spread throughout the scrubland, as well as the ubiquitous wild boar. The same is not the case with the bucardo or mountain goat of the Pyrenees, which became extinct in the year 2000 due to the neglect and abandonment of the authorities. Marmots abound and are frequently seen among the alpine grasslands. Much more difficult to see is the Pyrenean desman, a small and strange nocturnal insectivore endemic to this mountain range and some areas of the Central system. Also noteworthy is the presence of stoats, squirrels and hedgehogs. In total there are about 42 species of mammals in the Pyrenees. Since 2014, the ibex has been reintroduced in the French Pyrenees, specifically in the Ariège and in the Pyrenees National Park, from individuals from the Sierra de Guadarrama.

Among birds, the bearded vulture is very remarkable. Extinct in almost all of Europe, it is in the Pyrenees where the species has found its last refuge, currently expanding and providing specimens for breeding and recovery projects in the Alps. It is believed that 90-95 pairs and 500-600 bearded vultures roam the Pyrenees. The great predator of the Pyrenean air is the golden eagle, followed by a mix of nocturnal and diurnal species such as honey bees, red or black kites, hawks, kestrels, eagle owls or the extremely rare boreal owl that went from being considered extinct to offering a population of around 80 couples; as well as necrophagous birds, such as the griffon vulture, the Egyptian vulture and the expanding newcomer black vulture.

In the forest, the capercaillie, clearly in danger of extinction and greatly affected by mass tourism, seems to be in decline when speaking of the Spanish side (four males in Navarra, 75 in Aragon and about 450 in Catalonia), and very well preserved in the French area (around 3500 males). Along with it, some 120 species of small birds, including the black woodpecker, woodpecker, white-backed bill, wryneck and wallcreeper. In the high mountains lives one of the most appreciated Pyrenean species, the white partridge or alpine ptarmigan. The 700 pairs of this prodigious and elusive animal show that it is still one of the last untouched regions of Western Europe.

The Pyrenees has abundant populations of reptiles and amphibians, among which the asp viper, the Pyrenean newt, the salamander and the grass frog stand out. There are several types of snakes, including the bastard snake, the viperine snake and the European smooth snake.

Human beings have practiced grazing in the Pyrenees since Neolithic times. In Bisaurri (province of Huesca) remains of goat transhumance from the 5th millennium before our era have been found.

Climate

The climate of the Pyrenees is mountainous, with higher rainfall and lower temperatures than the surrounding territories. It also forms the climatic border between the predominant oceanic climate in the northwest and the Mediterranean climate in the southeast (with continental nuances to the south).

There is a decrease in rainfall from west to east and from north to south, with the pre-Pyrenean valleys of western Catalonia being the driest areas of the mountain range. In the central Pyrenees, rainfall moderates with regular rates (1,000 to 1,500 mm/year in the middle mountains, locally 2,000 mm in the highest peaks of the western Pyrenees) and the temperature range increases (at 1,200 m: 0 °C in January, 14 °C in July). Right at the eastern end, rainfall increases again due to its proximity to the Mediterranean, which, although infrequently, sometimes generates levante. The cross-border region located between Canigó and Olot is especially prone to receive intense rainfall (1,000 to 1,500 mm/year), although during the summer the drought is very present.

The oceanic influence from the northwest, coming from the Cantabrian Sea, is intense in the Navarrese Pyrenees, with cumulus rainfall of 1,500 to 2,500 mm/year with relatively mild winters and cool summers (averages of +1 °C in January and +13 °C in July at 1200 m altitude). This influence extends to four fifths of the range on the northern slopes (as far as Aude), and yet it penetrates little on the southern slopes.

On the southern slope, the rainfall regime is essentially fed by disturbances from the southwest of Atlantic origin, which suffer a continental influence during their journey through the peninsula and are reactivated upon contact with the Pyrenean relief. Rainfall is less frequent but often more intense than on the northern slope, which explains the high number of hours of sunshine despite having similar rainfall records (1,000 to 1,500 mm/year), except for the arid foothills (in around 500 mm/year). The temperate oceanic air is rejected by the high mountains, where winters are relatively cold and summers are mild (at 1,200 m: 0 °C in January, +15 °C in July).

Climate change in the Pyrenees

Current climate change in the Pyrenees is perceived in the form of an increase in the average annual temperature and a change in the rainfall regime.

Throughout the Quaternary period there have been evidences of variations in temperature, with various cycles of glaciation-deglaciation. However, since 1850 temperature variations have been at an unprecedented rate. These are related, in large part, to climate change and global warming, caused above all by the excessive human activity of emission of greenhouse gases resulting from the burning of fossil fuels.

In the joint analysis on a Pyrenean scale carried out by the Pyrenean Observatory of Climate Change (OPCC-CTP) in the OPCC-POCTEFA EFA 235/11 project, it is concluded that in the last decades (1959-2010) the temperature has has seen an increase of 1.3ºC, with a trend of 0.2 ºC per decade. This increase in temperature is the most prominent in the entire Catalan territory.

Future projections of temperature for the Pyrenees region show a progressive increase in both maximum and minimum temperatures throughout the 21st century. Depending on the emissions scenario considered, this increase will be greater (more emissive scenario) or less (less emissive).

Regarding the rainfall regime, climate models do not predict a significant decrease in the total annual amount, with records of around 2.5% decrease in rainfall per decade, but seasonal changes are expected, with longer episodes of drought and low water levels, as well as an increase in extreme weather events, with more frequent torrential rains, hail and severe storms.

The changes described in the average annual temperature and in the rainfall regime trigger changes to the entire mountain range. An example is the disappearance of more than 50% of the Pyrenean glaciers in the last 35 years and the high state of retreat of the rest, which, in turn, has implications for the ecosystem and the water cycle.

Geological risks associated with climate change

An increase in the frequency of landslides is expected in the Pyrenees area as a response to a weakening of the terrain due to subsidence or landslides caused by:

- Loss of volume to melt the permafrost result of rising temperatures. The presence of permafrost in the Pyrenees is limited above 2000m along the entire mountain range: it is possible to find it at the summits of Tossa d’Alp, Sierra del Cadí, Cotiella and Tendereña; and it is likely to find it in the highest sectors of the main mountain ranges of the Puigrós to the summits of the Sierra de Collarada. In the highest massifs and with greater extensions on the 2700 m is where the probability of finding permafrost is higher (Argualas-Infierno, Panticosa, Vignemale, Monte Perdido, La Munia, Punta Suelza, Bachimala, Perdiguero, Posets, Maladeta, Besiberri, Colomers, Puguera, Pica d'Estats). However, in all these sectors, there is no inhabited population and infrastructures are very limited. In the north-west side of the Vignemale massif, there has been an increase in subsidence phenomena in recent years, attributed to permafrost defrosting phenomena.

- Raw level rise in episodes of intense precipitation.

- Decrease in mechanical resistance of materials as a result of increase in forest fires (resulted from temperature rise and increased drought periods).

In addition, a greater number and magnitude of wet snow avalanches is also observed and expected.

Environmental risks associated with climate change

The environmental risks related to climate change in the Pyrenees mountain range are the following:

- Decrease in the annual average contributions of the Pyrenean rivers due to increased drought periods and thus increased evaporation, as well as the shorter duration of the snow mantle. This is also influenced by changes in soil and plant cover uses, which increase evapotranspiration, as well as climatic causes.

- Changes in the monthly river regime: increase in the flow rate during winter (due to the decline in winter snow accumulation), advance and decrease in spring dehydration flows, and decrease in flow rates in summer and autumn (due to increased frequency and intensity of droughts).

- Decrease in the amount of groundwater product of changes in the recharge and discharge of aquifers.

- Decrease in water quality due to a lower dilution effect of pollutants because there is less water.

- Decrease 20 per cent thickness of the snow mantle by an average increase of 1oC, as well as 25 days less than annual duration of the mantle.

- Reduction up to 78% of the accumulation of snow below 1500 m in the last quarter of the 21st century.

Leisure

This mountain range has large spaces conditioned for leisure, offering great possibilities due to its beauty and climate. The facilities for practicing skiing are those that require the most extensive space and have profoundly modified the use of land in the high mountains. Below are the ski resorts in the Pyrenees.

- In the Spanish part

Candanchú, Astún, Formigal, Panticosa-Los Lagos, Cerler, Boí Taüll, Baqueira Beret, Port Ainé, Port del Comte, Espot Esquí, Tavascan, La Molina, Masella, Vall de Núria, Vallter 2000, Rasos de Peguera.

- In Andorra

Ordino Arcalis, Pal Arinsal, Pas de la Casa-Grau Roig, Soldeu el Tarter, La Rabassa.

- In the French part

La Pierre-st Martin, Artouste, Gourette, Luz Ardiden, Cauterets, Hautacam, Bareges, Gavarnie-Gèdre, La Mongie, Piau Engaly, Saint Lary, Val Louron, Peyragudes, Luchon Superbagneres, Porte Puimorens, Ax-les- Thermes, Font-Romeu, Les Angles, Puyvalador, Formiguères, Puigmal 2600, Cambré d'Aze, Guzet, Les Mont d'Olmes, Ascou-Pailheres, Mijanes-Donezan.

Pyrenees climbers

Some scientists and mountaineers who have excelled in the study of these mountains are:

- Louis François Ramond de Carbonnières. Naturalist (1755-1827)

- Franz Schrader. Geographer (Burdeos, 1844-Paris, 1924)

- Henry Russell. Count Russell-Killough (Toulouse, 1834-Biarritz, 1909)

- Lucien Briet. Writer, photographer and explorer (Paris, 1860 - Charly-sur-Marne, 1921)

- Pedro Montserrat Recoder. Botanics (Mataró, 1918-2017)

- Albert de Franqueville. Botanics (?)

Contenido relacionado

Tachira State

Port Royal

Hectare