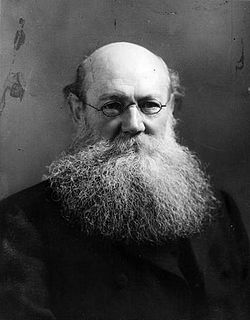

Pyotr Kropotkin

Prince (kniaz) Pyotr Alekséyevich Kropotkin, sometimes also known in Spanish as Pedro Kropotkin (Russian: Пётр Алексеевич Кропоткин; Moscow, December 9, 1842 - Dmitrov, February 8, 1921) was a Russian geographer, zoologist, and naturalist, as well as a political and economic theorist, writer, and thinker. He is considered one of the leading theoreticians of the anarchist movement, within which he was one of the founders of the school of anarcho-communism, and developed the theory of mutual support.

Born into an aristocratic landed family, he attended military school and later served as an officer in Siberia, where he participated in several geological expeditions. He was imprisoned for his activism in 1874 and managed to escape two years later. He spent the next 41 years in exile in Switzerland, France (where he was imprisoned for nearly four years), and England. He returned to Russia after the February Revolution in 1917, but was disappointed by the Bolshevik form of state socialism.

Kropotkin was an advocate of a decentralized communist society, free from central government and based on voluntary associations of autonomous communities and worker-run businesses. He wrote many books, pamphlets and articles, the most prominent being The Conquest of Bread and Fields, Factories and Workshops ; and the main scientific offering of him, Mutual Support . He also contributed to the article on anarchism in the 1911 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica and left an unfinished work on anarchist ethical philosophy.

Life

Kropotkin was born in Moscow on December 9, 1842, into a noble family. His father, Prince Alexei Petrovich Kropotkin, owned large estates in three provinces, and had about 1,200 serfs. Through his father's line his lineage was traced back to the Rurik; his mother, Yekaterina Nikolaevna Sulimá, was the daughter of a Russian general.

By order of Tsar Nicholas I, at the age of twelve he entered the Corps of Pages in St. Petersburg, Russia's most select military academy, which supplied the empire with its elite advisers and officials. Although Kropotkin detested the military discipline of the school, his academic training was intensive, receiving a rationalist and liberal education, with a strong emphasis on the sciences.

Explorer and Geographer

After completing his training, he served in the Russian Army from 1862 to 1867. During this period, he was commissioned on an expedition to Siberia as part of his military service. Kropotkin decided to leave for that destination - being able to choose a more comfortable one - to get away from the life of the capital's court, which was unpleasant and oppressive to him. He left for his post at Irkutsk on June 24, 1862, and was appointed aide-de-camp to General Kúkel; finally they settled in the village of Chitá, the regional capital.

The five years I spent in Siberia were very instructive to me regarding human character and life. I came into contact with men of all conditions, the best and the worst; those who were at the top of society and those who vegetated in their very background; that is, the vagabonds and the so-called cobbled criminals. I had plenty of occasions to observe the habits and customs of the peasants in their daily work, and even more, to appreciate how little the official administration could do in their favor, even when they were encouraged by the best intentions.P. Kropotkin; Memories of a Revolutionary.

His main task was to make an assessment of the cruel Siberian prison system for its reform, which impressed him deeply by revealing the shortcomings of the state bureaucracy and administrative corruption, as well as allowing him to observe the first forms of direct and autonomous cooperation between peasants and hunters. In Siberia he met the Russian poet Mikhail Larionovich Mikhailov, who had been sentenced to forced labor for his revolutionary ideas, who introduced him to anarchist ideas, recommending that he read Proudhon. These years in Siberia were decisive for the Kropotkin's subsequent ideological evolution:

Even though I did not then forge my observations in terms similar to those used by militant parties, I can now say that I lost in Siberia all the faith that could have previously had in the discipline of the State, thus preparing the ground to become anarchist.P. Kropotkin; Memories of a Revolutionary.

Between 1864 and 1866, he made several explorations into the unexplored territory of Manchuria. The last expedition was the most scientifically fruitful, covering the mountainous region of northern Siberia between the Lena and Amur rivers. This company provided invaluable scientific knowledge: it helped to better understand the geographical structure of the Siberian region; the discovery of fossil remains contributed to the elaboration of his later glacial theories; he enriched knowledge about the Siberian fauna, providing Kropotkin with data on mutual support (or intraspecific cooperation) and altruism in animal societies; and finally, the route from Chita and the Lake Baikal region to the northern tundra was discovered.

An insurrection by Polish prisoners in Siberia and its cruel repression by the tsarist authorities caused Piotr Kropotkin and his brother, Alexander, to decide to abandon military service. He returned to St. Petersburg in 1867, entered the University, and submitted to the Russian Geographical Society a report on his Vitim expedition, which was published and earned him a gold medal. He was appointed secretary of the Physical Geography section of the Russian Geographical Society. He explored the Finnish and Swedish glaciers on behalf of the aforementioned group from 1871 to 1873. His most important work at this time was the study of the orographic structure of Asia, where he refuted the hypotheses, rather conjectures, based on the alpine model proposed. by Alexander von Humboldt. Although other researchers later discovered more complex structures, the general lines of the approach devised by Kropotkin have remained valid to this day.

Another work of great importance was the report he wrote on the results of his expedition to Finland. In 1874 he gave a lecture in which he expounded his theory, according to which the ice sheet of the glaciation had reached the center of Europe; an idea that went against the conventional wisdom of the time. His proposal generated a controversy, which ended with its subsequent acceptance by the scientific community.

Finally, Kropotkin's third major contribution to the theory of geographic science was his hypothesis about the desiccation of Eurasia as a consequence of the retreat of the glaciation of the preceding era. All these ideas were conceived when he had not yet turned 30, which presupposed a great future as a researcher. The prestige of his geographical work was so considerable that he was proposed as president of the Physical Geography section of the Russian Geographical Society, but Kropotkin did not accept the appointment, because his interest had turned to revolutionary activities:

In the autumn of 1871, I was occupied in Finland, walking slowly to the coast, along the recently built railroad, carefully observing the places where first the unequivocal samples of the primitive sea extension should appear, which followed the glacial period, I received a telegram of the sweaty corporation, in which I was told: "The Council begs you to accept the position of secretary of the Society." At the same time, the outgoing secretary strongly begged me to welcome the proposal.My hopes had been realized; but at the same time, other ideas and other aspirations had invaded my thinking. After meditating carefully on what I should answer, I telegraphed: "Thank you very much; but I cannot accept."P. Kropotkin, Memories of a Revolutionary

Revolutionary Thoughts

While conducting these investigations, he also devoted himself to studying the writings of leading political theorists and began to sympathize with the plight of peasants. His own observations, his direct experience and his intimate contact with the misery and poverty of the Russian and Finnish peasantry, during his scientific work as an explorer, were the causes that prompted Kropotkin to abandon scientific activity.:

But what right did I have to these enjoyments of an elevated order, when everything around me was nothing but misery and struggle for a sad bite of bread, when it was little that I spent to live in that world of pleasant emotions, there was a need to remove it from the mouth of those who cultivated wheat and had not enough bread for their children? From someone's mouth it must be taken forcibly, since the added production of humanity remains so limited... That's why I responded negatively to the Geographic Society.P. Kropotkin, Memories of a Revolutionary

The inheritance received on his father's death gave him access to copious financial resources, which allowed him to undertake a three-month trip to Western Europe. In February 1872, he left Saint Petersburg for Zurich (Switzerland) to see first-hand the situation of the European labor movement, where he made contact with the group of Russian exiles who were strongly influenced by Bakunin's ideas. Among these were his relative Sophia Nikolaevna Lavrova, Nadezhda Smetskaya, and Mikhail Sazhin (a disciple of Bakunin better known as Armand Ross). In Geneva he became a member of the First International. First of all, he visited and contacted the Marxist sectors, especially the Russian group led by Nikolai Utin. But he did not approve of the type of socialism or the political style promoted in the First International. After five weeks of meeting the Marxist sector, very upset by the opportunistic behavior of its leaders, he decided to meet the groups of the Bakuninist tendency. The anarchist Nikolai Zhukovsky recommended that he leave Geneva and travel to Jura, where the movement was strongest.. Kropotkin studied the most radicalized program of the Jura Federation in Neuchâtel and spent a long time in the company of its most prominent members, definitively adopting the anarchist vision. There he visited James Guillaume —a companion, friend and later biographer of Bakunin—, with whom befriended. At the beginning of May he was already back in Russia. Once in Saint Petersburg, he resumed his geographical research and took an active part as a revolutionary propagandist linked to the Tchaikovsky Circle, invited by the geographer Dimitri Klements.

Arrest and escape

Meanwhile, Kropotkin continued his research work in Finland and his collaborations with the Geographical Society. In Saint Petersburg, he attended the evening meetings of the Tchaikovsky Circle disguised as a peasant and under the assumed name of Borodin, by which time many of his companions had been detained by the Tsarist police.

During the two years I have been talking, many arrests were made in both St. Petersburg and the provinces. We did not spend a month without experiencing any loss, or we knew that certain members of this or that provincial group had disappeared. By the end of 1873, arrests became more and more frequent. In November, one of our main centers, located in an extreme neighborhood of the capital, was invaded by the police. We lost Peróvskaia and three more friends, having to suspend all our relations with the workers of this arrabal. We founded a new meeting point outside still, but soon we had to leave it. The police removed the vigilance, and the presence of a student in the neighborhoods of the workers was at the point warned, circulating spies among the workers, to whom they did not lose sight. Dimitri, Klementz, Serguéi and I, with our tsars and our look of peasants, we went unnoticed, and we continued to frequent the land guarded by the enemy; but they, whose names had acquired great notoriety in those neighborhoods, were subject to all the investigations; and if they had been found casually in one of the night records at a friend's house, in the act the arrests.P. Kropotkin, Memories of a Revolutionary

In late 1873, the day after declining the chairmanship of the Geographical Society, Kropotkin was arrested by the police.

The night went unnoticed. I took a look at my papers, destroyed everything I could commit to someone, fixed my effects and set out to leave (...) and I went down quickly, leaving the house. At the door there was only one point car; I rode on it, and the driver took me to the Nevsky Prospekt. At first no one persecuted us, and I considered myself safe; but soon I observed that there was another carriage to run after ours, and having had to moderate his march the horse that led us, he took the lead. In it I saw with surprise one of the two weavers who had been arrested, accompanied by another person. He showed me with his hand, as if I had anything to tell me, and I ordered the coach to stop. Maybe—I thought—it was released and I have something important to communicate. But as soon as we stopped, the one accompanying the weaver—was a policeman— cried out, "Mr. Borodin, Prince Kropotkin, you are under arrest!" He signaled the guards, who abound so much in the main streets of St.Petersburg, and at the same time he jumped into my car and showed me a role with the seal of the capital police, saying at the same time: "I have a command to lead you to the general governor to give an explanation."P. Kropotkin, Memories of a Revolutionary

Transferred to the offices of the secret political police, the Third Section, he was interrogated for a few days. His arrest caused a sensation in St. Petersburg, in addition to the irritation of the emperor, since Kropotkin had long been his personal adjutant. He was imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress in a solitary, dark and damp cell. The notables of the Geographical Society, his friends and, especially, his brother Aleksandr intervened on his behalf to allow him to continue his geographical research, so he could access books, paper and pencils. At the beginning of 1875, his brother was arrested by the tsarist regime for writing a letter to Piotr Lavrov. His brother's arrest and the dismantling of the revolutionary circles—some 2,000 arrests were made—caused a strong psychological collapse in Kropotkin.. There was also a physical collapse caused by scurvy.

In March 1876 he was transferred to the St. Petersburg prison, where living conditions were even more unsanitary than in the fortress, although there were many more facilities for receiving visitors and breaking isolation. But his physical deterioration worsened, endangering his life, so the doctors ordered his transfer to the hospital next to the St. Petersburg Military Prison. The change to an airy, illuminated and clean environment, with a better diet, favored the recovery of his health. Meanwhile, his friends began to hatch plans for his escape from prison. After various preparations, agreeing on a system of signals with the outside, Kropotkin escaped by running through the prison yard where he went to practice his daily exercises, when the gate was opened to give way to the carts of the firewood suppliers. Pursued by the guards, he got into a waiting car and got lost in the crowd.

I saw with terror that the carriage was occupied by a man dressed in plainclothes and with a military hat, who sat without turning his head back to me. My first impression was that I had been sold. The comrades told me in their last letter: "Once on the street, don't give yourselves up; you will not lack friends who defend you in case of need." I did not want to jump into the car, if I was occupied by an enemy; but as I approached him, I noticed that the individual had blonds very similar to those of one of my best friends, who, although it did not belong to our circle, professed me true friendship, to which I corresponded, and on more than one occasion I could appreciate its admirable value, and to what extent their forces became bruised in the moments of danger. Is it possible—I said—to be him? And I was about to pronounce his name, when, holding on time, I touched the palms, without failing to run, to draw his attention. Then he turned to me and I knew who he was. "Go up, come up soon!" he shouted with a terrible voice, and then, heading to the carrior to revolve in his hand, he added: "To the gallop, to the gallop, or to leap the lid of the brains!" The horse, which was an excellent animal, bought expressly for the case, came out in the act galloping. A crowd of voices resonated behind our back, shouting, "Stop them! Stop them!" while my friend helped me put on an elegant coat and a pin.P. Kropotkin. Memories of a revolutionary.

After temporarily taking refuge in a house, he changed clothes and was taken to a barbershop, where his thick beard was shaved off. Then they set off for a busy St. Petersburg boulevard and dined in full view of everyone in a trendy restaurant, eventually hiding out in a small town on the outskirts. Meanwhile, the security forces searched the houses of his friends, without finding any clues. Dressed as a military officer, Kropotkin headed for the small port of Vaasa, on the Gulf of Bothnia, embarking for Sweden and continuing on to Norway. From there he took a British ship to the port of Hull, England.

The Long Exile

In early August 1876, Kropotkin landed in Hull, under the assumed name 'Aleksei Lavashov'. He settled in Edinburgh, but soon moved to London, where he had more means of earning a living. He began to collaborate with the publications The Time and the prestigious Nature , befriending the magazine's deputy editor, James Scott Keltie. At the same time, he resumed epistolary contact with James Guillaume, a resident of Switzerland, who contacted him with the Bakuninist Paul Robin, who became famous as a sexual reformer, and who promoted birth control and the elimination of prostitution. Kropotkin and Robin had debates and discussions on social issues, revealing a puritanical facet in the thinking of the former Russian prince.

After a short period in England, he settled in Switzerland, arriving in Neuchâtel in December 1876, where he joined the Jura Federation. There he met Carlo Cafiero and Errico Malatesta, the two most prominent members of the Italian section of the International. Determined to settle on the continent, he made a brief trip to England to settle labor issues with the magazine Nature, leaving on January 23 for Ostend and from there to Verviers (Belgium), to try to organize the movement local, but the defection of his friend Paul Brousse led Kropotkin to continue on to Geneva. There he met his old friend, Dimitri Klemetz, and contacted the famous anarchist geographer Eliseo Reclus in Vevey. Together with Brousse, and with the intention of clandestinely influencing other regions from Switzerland, he launched a relatively successful anarchist newspaper in French (L'Avant Garde) and another in German (Arbeiterzeitung), which flopped and stopped coming out a few months later. Kropotkin went to Verviers, in Belgium, to participate in the last congress of the Bakuninist section of the First International, where he acted as a delegate of the Russians in exile and carried out the task of writing the minutes. Due to rumors that he would be arrested he had to leave the congress, embarking from Antwerp to London.

Next, he traveled to France, contacting Andrea Costa, continuing the studies on the French Revolution that he had begun in London. Kropotkin's clandestine activities drew police attention in early 1878, for which he had to return to Geneva at the end of April. Shortly after he visited Spain, to learn about the situation of the movement, a visit that made a strong impression on him when he met a mass anarchist movement, returning to Geneva in August. the noticeable decline of the Jura Federation. On October 8, 1878, he married the young Russian émigré Sofia Ananiev. On December 10, the Swiss authorities closed L'Avant Garde, and then briefly detained Brousse. They started a new newspaper to follow the previous one, and on February 22 Le Révolté appeared, which due to a lack of participants was written almost entirely by Kropotkin. The newspaper was a success, and by April 1879 it had 550 subscribers, which enabled them to buy their own printing press on credit, founding the Imprimerie Jurassienne.

Theoretical and propagandist

From the pages of Le Révolté, Kropotkin presented the first formulations of anarcho-communism, his main contribution to anarchist ideology. The first article on the subject appeared on December 1 and was entitled The Anarchist Idea from the Point of View of its Practical Realization. He affirmed there that the revolution should be based on the federations of local communes and independent groups, evolving society from a collectivist stage of appropriation of the means of production by the communes, towards communism. During 1880, invited by Eliseo Reclus to collaborate in his Universal Geography, Piotr and Sophia moved to Clarens.

Here, with the contest of my wife, with whom I used to discuss all the events and the works performed, and that I exercised a severe literary criticism of the latter, it was where I produced the best I did for the Révolté, among which is the appeal. To the youngso much acceptance found everywhere. In a word, in this place I laid the foundations and brought the general lines of everything I wrote later. In Clarens, in addition to the deal with Eliseo Reclus and Lefrançais, which I have always cultivated since, found me in intimate relations with the workers, and although I was working a lot in the geography I was still given to contribute more than ordinary to anarchist propaganda.P. Kropotkin; Memories of a revolutionary.

In March 1881, his friend Stepniak told him the news of the assassination of Tsar Alexander II by members of the Naródnaya Volya group. The repression of the revolutionary movement, with the execution of his former Tchaikovsky Circle comrade, Sofia Peróvskaya, outraged Kropotkin, who printed a pamphlet The Truth About Executions in Russia and was a speaker at events protest. The Geneva police questioned him but ultimately decided not to arrest him. On July 10 he left for Paris and then for London, to attend as a delegate to the International Revolutionary Socialist Congress. Due to Kropotkin's poverty, his friend and classmate, Varlaam Nikolaevich Cherkesov, took up a collection to pay for his trip. In a letter to Malatesta, Kropotkin explained his financial difficulties:

I turned him and everything else usually takes me a week, so I have two weeks left for a month in which I have to win 150 to 200 francs for us two, 50 francs for Robert, another 40 for the Russians, 30 for correspondence, 10 to 15 for paper, etc; in total more than 350 francs.P. Kropotkin

Kropotkin participated in the congress in London, but ended up disappointed by the chaotic tone of the discussions and because in the end the issue for which it had been called was not dealt with: the formation of a new International. He stayed in England for a month and returned to Switzerland. Shortly after his return, he was expelled by the Swiss government due to pressure from the Russian Empire. He left Geneva on August 30 and settled in the small French town of Thonon, on the other side of Lake Geneva. The writing of Le Révolté was left in charge of Herzig and Dumartheray, although Kropotkin would continue to collaborate from abroad. They stayed there for two months until Sofia finished her high school studies in Geneva.

In November 1881 he traveled with his wife to England, giving some conferences on his way to Paris, where he contacted Jean Grave. In England he did not have many contacts with anarchists, with the exception of Malatesta, Cafiero and Eliseo Reclus, when they passed through the island. During 1882 he became friends with the English Marxists Ernest Belfort Bax and H. M. Hyndman; the latter introduced him to James Knowles, editor of The Nineteenth Century , a publication with which he would collaborate for three decades. He continued to write for Nature , The Times and The Fortnightly Review , as well as for the Encyclopedia Britannica. In Le Révolté he published two important articles: Law and Authority and Revolutionary Government . During his stay in England he became very involved with the situation in Russia, and exposed it in workers' clubs, in some rallies that he organized together with Tchaikovsky; then they exposed the anarchist ideology. Although the attendance was scarce, this situation changed when he visited the miners' circles in Scotland, where his exhibitions attracted crowds of workers.

The depressing and listless atmosphere of London prompted the couple to return to France, where the anarchist movement was flourishing and active, arriving in Thonon on October 26. There they gave accommodation to a young brother of Sofía, dying from tuberculosis. The revolutionary activities in Lyon, where there were some 3,000 active anarchists, the disorders caused by the crisis in the silk industry and some attempts at violence, were the excuse to arrest Kropotkin, who had nothing to do with the riots, along with sixty anarchists.. On December 21, 1882, Kropotkin was arrested by the police, hours after the death of his young brother-in-law. During the funeral, Reclus and other anarchists mobilized the peasants of the area, as a form of protest against the arrests.

The French government wanted to make that one of those great processes that made a strong impression in the country; but there was no means of envolving the anarchists imprisoned in the cause of the explosions, since it would have been necessary to conclude by bringing them to a jury that would probably have absolved us, and consequently, the political Machiavellian was adopted to pursue us for having belonged to the International Workers' Association. There is a law in France, voted immediately after the fall of the Commune, whereby anyone can be brought before an investigating judge, for having belonged to that society. The maximum penalty is five years, and the government always has the assurance that the ordinary court will be pleased.P. Kropotkin, Memories of a Revolutionary

Prison in France

He was accused of belonging to the International, and sentenced to five years in prison and a fine of 1,000 francs for his anarchist activities; it was the most severe sentence of all. The independent press, including even the moderate Journal des Economistes, protested against the convictions, criticizing the magistrates for convicting them without grounds. Anarchists, especially Bernard, Gautier and Kropotkin, took advantage of the trial to publicize their ideas by making fiery speeches.

He was transferred from Lyon to Clairvaux prison, in the old Saint Bernard Abbey, where he was given political prisoner status. During this period he continued to write for Universal Geography and the Encyclopedia Britannica, in addition to continuing his contributions to The Nineteenth Century, highlighting the article What Geography ought to be. The conditions of detention this time were not so suffered as when he was a prisoner in Russia, since the authorities allowed them to grow vegetables, play bowling and work in a bookbinding workshop. Kropotkin took advantage of the time to teach languages, mathematics, physics and cosmography to the other inmates. They could write and receive letters, under a regime of censorship. They could receive books and magazines, but not newspapers, much less of a socialist tendency.

Kropokin received from Paris the concern of the French Academy of Sciences, which offered to send him books for his research; Solidarity was also heard from England, drafting a petition in his favor, signed by 15 university professors, the directors of the British Museum, the Royal Society of Mines, the Royal Geographical Society, the Encyclopedia Britannica, and nine English newspapers, in addition to personalities like William Morris, Patrick Geddes and Alfred Russel Wallace. The petition was presented to the French Minister of Justice by the writer Victor Hugo, who rejected the petition. Towards the end of 1883 Kropotkin contracted malaria, an endemic disease in the region, compromising his health for a few months. Meanwhile, Reclus gathered the articles from Kropotkin for Le Révolté in a volume that was published in Paris in November 1885, entitled Words of a Rebel.

The demands for freedom put so much pressure on the French government that Prime Minister Freycinet was forced to declare that "diplomatic reasons prevent the release of Kropotkin," generating a major public reaction by admitting the demands of the Tsar in the domestic policy of France. The French government had no choice but to pardon the detainees and release them on January 15, 1886. Kropotkin and Sophia, financially bankrupt, moved to Paris, where they were able to obtain more adequate means of subsistence. To prevent a possible deportation to Russia by the French government, Kropokin decided to settle in England, not without pronouncing on February 28, 1886, on the eve of his departure, the speech Anarchism and its place in socialist evolution in front of several thousand people.

His experiences as a prisoner in Russia and France led Kropotkin to reject all forms of imprisonment as a form of social and moral recovery of the detainees. Later these impressions would be turned into a text published in England in March 1887, In Russian and French prisons. The first edition of this book was bought by agents of the Russian government to prevent its dissemination, managing to destroy most of the copies. It was finally republished years later.

...I have been able to convince myself that, in terms of its effects on the prisoner and its results for society in general, the best reformed prisons — whether they are cellular or not — are so bad, or even worse, than the dirty old prisons. They do not improve the prisoner; on the contrary, in the vast and overwhelming majority of cases, they exert on them the most regrettable effects. The thief, the swindler and the rascal who have spent a few years in a prison, leave him more willing than ever to continue along the same path, finding himself better prepared for it, having learned to do better, being more in hiding against society and finding a more solid justification of his rebellion against their laws and customs, which is why they have, necessaryly and inevitably, to fall deeper into the motto of antisocial acts than they have before.P. Kropotkin; Memories of a Revolutionary

The Years of Exile in England

Kropotkin and Sofia arrived in England in March 1886, where they stayed for 3 decades, leading a completely different and peaceful life, dedicated to scientific research and theoretical and ideological elaboration. His health was also greatly affected by the years in prison, affected by the English climate, which caused him chronic bronchitis. He settled in the London suburbs, and took up relatively sedentary habits, compared to his permanent mobility and agitation of the previous two decades.

One of his first activities was to found an editorial group for an anarchist newspaper, made up of Charlotte Wilson, Dr. Burns Gibson, as well as Kropotkin and Sofia, among others. The group was called Freedom (Freedom) and was dedicated to propaganda tasks, editing a newspaper and organizing conferences. Initially the group published their writings in Henry Seymour's newspaper, The Anarchist. Soon Kropotkin's intellectual authority made itself felt over the thought of the Tuckerian Seymour, and his newspaper declared his adherence to anarchist communism. Around this same time she became friends with William Morris. In April she moved into a cheap, sparsely furnished house in the Harrow area, on the outskirts of London. He continued to collaborate with various publications: The Ninteenth Century, Freiheit (by Johann Most), La Révolte (successor to Le Révolté), Nature and The Times.

The Freedom group split from The Anarchist after a dispute with Seymour, and in October 1886 the first issue of Freedom came out. It consisted of a 4-page spread written mostly by Kropotkin and Wilson, which was printed until 1888 in William Morris's Socialist League workshop. Meanwhile, Kropotkin's personal life was shaken by the news of the suicide of his brother Alexander in Siberia on August 6, who was his last family tie to Russia. The rise of socialist movements in England aroused the interest of the public towards anarchism, and Kropotkin became an active lecturer, visiting almost all the great cities of England and Scotland. On his visit to Edinburgh he became friends with Patrick Geddes, whom he would strongly influence in his thinking.

On April 15, 1887, their only daughter was born, whom they named Alejandra, in memory of her brother. At the end of that year he was very involved and concerned about the death sentences of those accused of the Haymarket attack in the United States. Kropotkin participated in the campaign for the release of anarchist prisoners and on October 14 he spoke at a large event in London, along with personalities such as William Morris, George Bernard Shaw, Henry George and Stepniak, although the defendants were finally executed on October 11. November. On November 13, he participated in a demonstration called by William Morris in favor of free speech in Trafalgar Square, which ended in serious riots. The Freedom group began to grow in membership and gain influence in the English socialist movement, joining many anti-parliamentarian members of W. Morris's Socialist League (who accepted Kropotkin's views, although he never declared himself an anarchist). The parliamentary faction of Eleanor Marx would finally split from this league in 1888. However, relations between the Freedom group and the anti-parliamentary Socialist League also deteriorated, marking a distance.

Writer, scientist and theorist.

From 1890 Kropotkin's activities as an agitator were less and less and his facet as thinker, intellectual and scientist began to strongly predominate. He wrote for many anarchist publications such as Temps Noveaux (with which he contributed free of charge) and other journalists such as the English The Speaker and The Forum or the American ones The Atlantic Monthly, The North American Review and The Outlook. He delivered dozens of lectures, highlighting those in cities such as Glasgow, Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, Manchester, Darlington, Leicester, Plymouth, Bristol and Walsall. His themes were so diverse that, in addition to anarchist theory, he dealt with literature, Russian politics, industrial organization, the prison system, naturalism, and the first expositions on his theory of mutual aid.

When Huxley, wanting to fight against socialism, published in 1888 The Nineteenth Centuryyour atrocious article Struggle for Existence ManifestoI decided to understandably present my objections to his way of understanding the fight, the same among the animals as among men, materials that I have accumulated for six years. I spoke of the particular to my friends; but I found that the interpretation of struggle for existence in the sense of the cry of war: Woe to the defeated! elevated to the height of a mandate of nature revealed by science, was so deeply rooted in this country, that it had become little less than in dogma.P. Kropotkin, Memories of a Revolutionary

From 1888 Kropotkin began writing his sociological work, writing three articles in The Nineteenth Century (“The Collapse of Our Industrial System;” “The Future Kingdom of Plenty;” and, “The industrial city of the future”), which would form the basis of the book Fields, factories and workshops, which he would publish later. Around this time he expounded in conferences his ideas on free distribution, voluntary work and the abolition of the salary system, based on the principle: "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need".

Throughout 1889 he wrote articles for Le Revolté and The Nineteenth Century on the French Revolution and its consequences, and in March 1890 he published the essay Intellectual work and manual work. Starting in September 1890, he published in The Nineteenth Century the first essays in response to Thomas Henry Huxley, which would eventually be brought together in his most prestigious scientific work: Mutual Aid: A Factor in Evolution. In 1891 he would write "La moral anarquista" and during 1892 he began to regularly write popular science articles for this same newspaper, exploring topics as diverse as geology, biology, physics and chemistry; The conquest of bread was also published in France, with a preface by Eliseo Reclus. By this time Kropotkin's reputation was growing, gaining great respect and success as a writer among the general public, in addition to academic recognition that materialized in frequent invitations to give lectures on scientific topics at the British Association, the University of London and the Teacher's Guild. In 1894 the Contemporary Review dedicated a laudatory article to him entitled "Our Most Distinguished Political Refugee".

During 1892 the Kropotkins moved to Woodhurst Road, Acton, but in 1894 they changed residence again, settling in a country house in Bromley, Kent. There he cultivated an orchard, had a workshop where he made his own furniture and an office whose walls were covered to the ceiling with books, according to the description of Rudolf Rocker, who visited him in 1896. In his residence he received visits from characters from all over the world such as Louise Michel, Fernando Tarrida del Mármol, Emma Goldman, Georg Brandes, among others.

The English anarchist movement began to become isolated in the face of the rise of parliamentary socialism; in 1895 the Freedom group, the Commonweal group and the Socialist League merged, with Alfred Marsh taking over as editor-in-chief, replacing Charlotte Wilson. Kropotkin – who was regarded by the general public as more of a savant scholar who, like an anarchist, continued to collaborate with the newspaper but without participating in propaganda, agitation or activism activities, devoting himself almost exclusively to intellectual activity. During the International Socialist Congress in London in 1896, the anarchists were prevented from participating by the parliamentarians, establishing a definitive split in the socialist movement. After protesting vigorously, the anarchists held a separate congress, although Kropotkin, somewhat in poor health, did not actively participate. New Year's Eve 1896 brought news that deeply affected Kropotkin: the deaths of his friends William Morris and Stepniak..

In 1897 he participated in the campaigns against the Spanish government, accused of torturing prisoners in Montjuich (Barcelona), but his health worsened and Sofía herself replaced him as lecturer, something that would become common from there on forward. That year he traveled to North America through the English Society for the Patronage of Science, which was holding a meeting in Toronto, Canada. In the United States he gave three lectures on mutual aid at the Lowell Institute in Boston, and another in New York. In the latter city he met with Johann Most, Benjamin Tucker and the socialist leader Daniel de Leon. In Pittsburgh he tried to visit Alexander Berkman who was in prison, but was not allowed. He also arranged to publish his Memoirs of a Revolutionary in installments in the Atlantic Monthly, which would later be published in book form in 1899. At the same time, he worked on updating and deepening the articles that would constitute the definitive edition of Fields, factories and workshops, also published that year. During the Boer War Kropotkin declared himself against and denounced the crimes of the English army, despite the fact that he could lead to his expulsion from the country.

He returned to the United States in 1901, visited Chicago, and lectured at major universities and at the Lowell Institute in Boston, where he discussed Russian literature, later published as a book in Ideals and realities of Russian literature. In New York he spoke at the Political Education League , at the Cooper Union before 5000 people and twice at a Fifth Avenue venue. He also gave speeches at Harvard and at Wellesley College. In addition, he attended various meetings and events organized by his anarchist friends, which were always well attended and lively. He returned to England in May and devoted himself fully to his theoretical work, completing the last articles of Mutual Aid, which would come to light in 1902.

His health ailments, especially his bronchial conditions, practically prevented him from returning to public life. In 1903 and 1904 he expounded his geological theory at the Geographical Society. In 1904 he published The Ethical Necessity of the Present Age and in 1905 The Morality of Nature . But that year he suffered a heart attack after a Decembrist tribute ceremony that nearly killed him. The Russian Revolution of 1905 refocused Kropotkin on the affairs of his native country. But in July he received the news of the death of his friend Eliseo Reclus; Kropotkin wrote articles in his memory for the Geographical Journal and for Freedom . In the autumn of 1907 he moved to a house in High Gate, where he finished his pending theoretical work, publishing in 1909 The Great French Revolution, The Terror in Russia and between 1910 and 1915 a series of articles in The Nineteenth Century on ethics and mutual aid, evolutionism, and biological heredity, taking a neo-Lamarckian side and criticizing August Weismann's ideas about germ plasm.

The European War and the Russian Revolution

In the last years of the XIX century the Russian anarchist movement had begun a certain flowering, which consequently brought an increase in the activity of émigré groups in Switzerland, France and England. In 1903 in Geneva appeared Jleb i volia (Bread and Freedom), which illegally introduced, came to influence Russia. Kropotkin and Cherkesov supported him by writing unsigned articles. Although Kropotkin's influence was notorious in theory, he was not so in other tactical questions and concrete political practice. His opposition to terrorism (that is, to assaults as a form of economic financing), contrasted with the practices of many small anarchist groups that operated inside Russia, destabilizing the tsarist regime.

He advocated expropriation, so that the free people would go to the stores and take the food and clothing they needed, always rationalizing. For the house it would act in the same way. Rents would be abolished, empty houses would be taken over by families living on the street. Those who had free rooms could be taken by people who needed them.

Declared that all men and women have the right to social welfare. She formulated ideas such as working five hours a day, having the rest of the free time to participate in playful tasks of individual interest. She would start contributing to society at the age of 25 and stop at 45.

He also demonstrated how countless associations function without state authority, such as the Red Cross or the English Lifeboat Associations. Moreover, the evolution of all these associations was dizzying, notorious and praised by all. The state, far from being the defender, is the oppressor and the cause of all the ills of the people.

It also showed a new and revolutionary idea. He told us about the organizing spirit of the town. Well, like the people, far from being a mass of savages guided by their common sense, capable of bringing "the new order" in the absence of any authority.

Kropotkin favored anarcho-syndicalism, the mass movement and participation in the soviets (as long as they did not become an authority body). Tactical discussions led Russian anarchists to hold two conferences in London in December 1904 and October 1906, and to publish a paper entitled The Russian Revolution and Anarchism in 1907. In these papers he had a strong influence. witness Kropotkin's thought, influenced by the revolutionary events of 1905. From then on Kropotkin began to think about returning to Russia to participate in the fight against autocracy.

His health continued to decline and in the autumn of 1911 he returned to his residence, establishing himself in Kemp Town, Brighton, his last home in England. For health reasons, for some years Kropotkin spent the winters abroad, not to suffer the weather. In these trips he visited Paris and the region of Brittany (France), Ascona, Bordighera and Rapallo (Italy) and Locarno (Switzerland), whose climate relieved his chronic bronchitis. In 1912 he left the International Congress of Eugenesia in London, where he exposed critical points of view towards the sterilization of people defended by some scientists. That year he participated in the campaign to prevent the deportation of Errico Malatesta to Italy, influencing the Liberal Cabinet Minister John Burns to suspend that measure. In December 1912, when he was 70 years old, he received emotive tributes and congratulations; in one of them that was held at the Palace Theatre in London, George Bernard Shaw, George Lansbury and Josiah Wedgwood spoke, among others.

After the 1905 revolution, anarchism in Russia experienced dizzying growth, with dozens of groups springing up all over the country. Kropotkin's works began to be published legally or illegally; His influence was found mainly among communist anarchists and anarcho-syndicalists. The émigré newspaper in which Kropotkin participated was dissolved and he was replaced by Listkí Jleb i volia , a task in which he collaborated with Alexander Schapiro and Maria Goldsmith. But in June 1907 he had to abandon his publication. He dedicated his energies to translating into Russian and editing a large part of his work, among which the edition of The Great French Revolution, completed in 1914, stands out. Kropokin also collaborated with the newspaper of émigré anarchists Rabochi Mir and in some issues of Jleb i volia, which reappeared briefly in 1910 in Paris.

During the years prior to World War I, breaking with the traditional anti-war anarchists, he sided with republican France against Bismarck's German Empire, which he considered the greatest danger, since he thought it was necessary to oppose Germany's extremely militaristic policy to generate a geopolitical counterbalance. At the start of the conflict, there was a breach between Kropotkin, Jean Grave and the anarchists who supported intervention in the war, with the international anarchist movement, which earned him strong criticism and the break with many of his old friends such as Dumartheray, Herzig and Luigi Bertoni. This attitude led him to a dispute with the members of Freedom, who published a letter by Malatesta devastatingly critical of warmongering from Kropotkin, a letter that represented the majority opinion of the anarchist movement.

After a violent argument with Thomas Keell, editor of Freedom, Kropotkin, Cherkesov, Sofia, and other pro-Allied anarchists parted company with the editorial group they were founders of. They expressed their rejection of the war and their disagreement with Kropotkin, who was supported by Jean Grave, James Guillaume, Paul Reclus, Carlos Malato, Christiaan Cornelissen; they signed a warmongering declaration known as the Manifesto of the Sixteen, and edited their own newspaper, La Bataille Syndicaliste. This manifesto was also answered by another manifesto opposing the war, supported by Malatesta, Shapiro, Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Thomas Keell and Rudolf Rocker, among others. Armand and Sebastian Faure.

Kropotkin and his group were virtually isolated not only within the anarchist movement, but also within the socialist movement in general. Kropotkin's position was used by Lenin to qualify him as a petty bourgeois and jingoist, and thus be able to attack the anarchists, the vast majority of whom were opposed to the war. Kropotkin lost contact with his old anarchist friends and secluded himself in his residence, until the first news about the fall of Tsarism arrived in March 1917.

Return to Russia and death

After the February Revolution, Kropotkin decided to return, excited by the turn of events. In the middle of 1917 he embarked incognito in Aberdeen bound for Bergen (Norway), but despite the secrecy he was received by a demonstration of workers and students. He crossed Sweden and Finland entering Russia after 41 years. Throughout the trip he received displays of support and affection for each town he passed. He arrived in Petrograd by railway at two in the morning, being greeted at the station by a military regiment, a band playing La Marseillaise , and a welcoming rally of 70,000 people.

This period was characterized by a frenetic participation in events, speeches and meetings, which seriously affected his deteriorating health. But his relationship with the bulk of the anarchist movement was not mended, as Kropotkin continued to insist that participation in the war would ensure the gains of the revolution; which "led him to equivocal situations and companies." The vast majority of anarchists did not support the war, which is why they maintained occasional relations with the Mensheviks, and other warmongering constitutionalist parties far from the revolutionary sector. Kerensky offered him a government post, a hefty monthly pension, and residence in the Winter Palace, but Kropotkin gracefully refused, though he did not refuse to offer his advice informally.

In August he left frenetic Petrograd and settled in Moscow, shortly thereafter participating in the All-Party State Conference as a speaker, where he was critical of Bolshevik policies, and in favor of a continuation of the war and the constitution of a federal republic. These reformist and moderate demonstrations were used by the Bolsheviks to discredit Kropotkin and strike back at the anarchists. The October Revolution put an end to the Kerensky government, with the Bolsheviks assuming power. The end of the war and the radicalization of the mass movement put an end to the ideological confusion that had gripped Kropotkin since his support for the Entente, and he took up his anarchist principles. He went to work in the Federalist League, a group of scholars of sociological problems that promoted federalism and decentralization, provided statistical data and studies to the public, but in mid-1918 it was suppressed by the Bolshevik authorities. Although Kropotkin was not personally affected by the repression (as they considered him harmless), the Bolsheviks began their repression not only against the Menshevik and Social Revolutionary opponents, but also against anarchist groups, organizations and newspapers, which had supported the movement. of masses in the October Revolution. This situation and the end of the war brought him closer to the Russian anarchists, with whom he restored his good relations, having dealings with Grigori Maksimov, Volin and Alexander Shapiro.

In the spring of 1918 Kropotkin received a visit from Nestor Makhno, peasant leader of the Ukrainian anarchists. In Dmitrov he was in charge of reorganizing the local museum, and devoted himself to finishing his Ethics (which would eventually remain unfinished), which had to interrupt his work for periods due to health problems. Kropotkin, despite his clash with the Bolsheviks, further rejected Western Allied intervention in Russian affairs. In early May 1919 he met Lenin in Moscow, with Kropotkin making a defense of the cooperatives that the Bolsheviks attacked, and criticizing the Bolsheviks' coercive methods and bureaucracy, although the general tone of the interview was cordial. He would later write to Lenin 3 times, but his requests and criticisms were never answered.

Bolshevik methods made Kropotkin harden his critical vision. This attitude has been witnessed by the visitors Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman, Alexander Shapiro, Ángel Pestaña and Agustín Souchy Bauer and by the letters that Kropotkin wrote to Georg Brandes and Alexander Atabekian. He wrote in June 1920 a "Letter to the Workers of the Western World"; where he exposed his anarchist conceptions and his criticism of the Revolution lucidly. In 1920 he wrote a harsh letter to Lenin reproaching him for the practice of threatening to kill prisoners of war to protect himself from his adversaries.

The news has appeared in the newspapers. Izvestia and Pravda that makes known the decision of the Soviet government to take as hostage some members of the groups of Sávinkov and Cherkov of the Social Democratic Party, of the Tactical Nationalist Center of the White Guards, and of Wrangel's officers, so that, in the event that an attempted murder against 108 soviets leaders is committed, such hostages are "extermined without mercy". Is there really no one near you who remembers your comrades and persuades them that such measures represent a return to the worst period of the Middle Ages and the religious wars, and is totally disappointing of people who have put themselves at the expense of creating society in line with the communist principles? Anyone who loves the future of communism can't be thrown into such measures......I think they should take into account that the future of communism is more precious than their own lives. And I would be glad that with your reflections, you give up this kind of action. With all these very serious shortcomings, the October revolution has brought enormous progress. It has shown that the social revolution is not impossible, which the people of Western Europe are already talking about starting to think, and that despite its flaws it is bringing some progress towards equality. Why then hit the revolution by pushing it to a path that leads it to its destruction, especially by defects that are not inherent in socialism or communism, but represent the survival of the old order and the old destructive effects of the unrestricted authority?P. Kropotkin

Kropotkin met again with Lenin, where he explained his views. From November his health began to deteriorate, and on December 23, 1920 he wrote his last letter to the Dutch anarchist P. de Reyger. In January he began to suffer from pneumonia, and despite medical care, he passed away at 3 a.m. on February 8, 1921, in Dmitrov.

Crowd funeral

The Bolshevik government offered an official funeral but the anarchist family and friends refused the offer. Russian anarchist groups formed a funeral commission to organize the ceremony, including Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman and Sasha Kropotkin. The local authorities barely allowed the publication of two pamphlets in his memory that had to go through prior censorship, so the anarchists reopened a printing press closed by the Cheka and published the pamphlets without prior censorship.

Meanwhile, hundreds of workers, students, peasants, officials and soldiers passed by the small house to say goodbye to the old revolutionary. Schools remained closed as a sign of mourning and children threw pine branches at the procession carrying Kropotkin's body. The coffin was taken to the railway station, and from there by train to Moscow. A crowd received the coffin and accompanied it to the Palacio del Trabajo. The anarchists pressured the government to provisionally release the detained anarchists and allow them to attend the celebration. Kamenev promised to release the detainees in exchange for the anarchists not turning the ceremony into a demonstration of repudiation of the government. In the middle of the act, only seven of the detained anarchists arrived, among whom were Aarón Baron and Grigori Maksimov.

The crowd of about 100,000 people accompanied the coffin the 8 kilometers to the Novodevichy Cemetery. They were followed by an orchestra playing Tchaikovsky's Pathetic Symphony. Hundreds of flags of political parties, scientific societies, unions and student organizations waved among the attendees. The black flags of the anarchists were also flying. The Tolstoy Museum also flew the black flag, and as protesters passed through Butyrka Prison, political prisoners extended their arms out of the barred windows to wave. Once in the cemetery, the orators were pronouncing their tributes; The last to speak was Aarón Barón, one of the provisionally released anarchist prisoners, who boldly protested against the Bolshevik government, prisons and torture against the opposition revolutionaries. Kropotkin's funeral was the last mass demonstration of Russian anarchism during Bolshevik rule.

Thought

Political

Until now, at the bases of anarchism we found the collectivization of the means of production, managed by workers' societies. We also find a salary according to what each one has done and the disappearance of the State and the government. Ideas arrived thanks to the contributions of Proudhon, Guillaume, Bakunin...

Even so, Kropotkin's libertarian communism was not exempt from some divergences from Proudhon's and Bakun's theses. Kropotkin based his thinking around three axes:

- How to organize production and consumption in a free society?: By collectivizing the means of production and the goods obtained, together with a rationalization of the economy and the creation of the self-sufficient commune (the commune suppresses the rural-city differences, creates an industrial decentralization and also suppresses the division of labour). In addition, contrary to capitalism, it does not govern the principle of maximum individual benefit, since it governs a more just and equal principle: "to each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs". Sustained everything in mutual support.

- Mutual support: In mutual support lies a wider interpretation in contrast to Darwinian evolutionism: Kropotkin demonstrates that cooperation and mutual assistance are common and essential practices in human nature. If solidarity for greed is renounced, it falls into social hierarchy and despotism.

- Moral and ethical conception: Only a moral based on freedom, solidarity and justice. In any case, science must be the guide to ethical and not supernatural foundations. Research into social structures must produce knowledge of human needs, a basis for the development of a free society.

Naturalist

In his role as a naturalist, he raised the importance of cooperation as a key factor in evolution parallel to competition. His most famous work, Mutual Aid, written from his experiences on scientific expeditions during his stay in Siberia, criticizes the ideas of Thomas Henry Huxley and Herbert Spencer (father of social Darwinism) who based natural selection in the struggle between individuals. Originally, the processes on which species based their intraspecific and interspecific interactions had been mainly related to two important concepts: "struggle for existence" and "altruism." Both terms were transcendental in the Darwinian conception of evolution. However, the first of them was for many the one that contributed more elements to explain the evolution of the species. Kropotkin, in order to refute the struggle for life as the central axis in evolution, carried out a series of studies in Siberia from 1862 to 1867 and observed that the species in that part of northern Asia, far from displaying a fierce struggle for survival, showed a behavior altruistic that he would define as «mutual support». In this way, altruism between the species was for him what would provide them with success in the struggle for existence.

His works were written in both English and French, initially becoming popular in other languages such as Spanish, currently there are copies in multiple languages.

Work

| Year | Original title | Title in Spanish | Editor/city |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1873 | Dolzhnyi-li my zaniat'sia rassmotreniem ideala budushchego stroia? | Should we consider the ideal of a future system? | Reproduced in Byloe, no. 17 (1921) |

| 1873 | Pugachev ili bunt 1773 goda | Geneva | |

| 1876 | A propos de la question d'Orient | On the question of the East | Bulletin de la Fédération Jurassienne de l'Association Internationale des Travailleurs. Geneva |

| 1876 | Research on the Ice age | Research on the glacial era | Notices of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society |

| 1877 | Nouvelles de l'extérieur: Russie | News from abroad: Russia | Bulletin de la Fédération Jurassienne. Geneva |

| 1877 | Les Trades Unions | Trade unions | Bulletin de la Fédération Jurassienne. Geneva |

| 1877 | Affaires d'Amérique | Americas Affairs | Bulletin de la Fédération Jurassienne. Geneva |

| 1877 | Bulletin international | International bulletin | L'Avant-Garde |

| 1877 | Le Vorwärts et le peuple russe | The Forward and the Russian People | Bulletin de la Fédération Jurassienne. Geneva |

| 1879 | Idée anarchiste au point de vue de sa réalisation pratique | Anarchist idea from the point of view of its practical realization | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1879 | Le Procès de Solovieff | The Solovieff process | Geneva |

| 1879 | The Situation | The situation | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1879 | La Décomposition des États | The breakdown of States | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1880 | La Commune de Paris | The Paris Commune | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1880 | L'Année 1879 | The year 1879 | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1880 | Le Gouvernement représentatif | The representative government | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1880 | Les Pendaisons en Russie | Executions in Russia | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1880 | The Commune | The Commune | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1880 | Aux Jeunes Gens | To the young | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1880 | The Question agraire | The agrarian question | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1880 | Les Élections | Elections | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1881 | L'Année 1880 | The year 1880 | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1881 | Les Ennemis du peuple | The enemies of the people | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1881 | La Commune de Paris | Paris commune | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1881 | The Situation in Russie | The situation in Russia | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1881 | The South Vérité les exécutions en Russie | The Truth About Executions in Russia | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1881 | L'Espirit de Révolté | The Spirit of Rebellion | I turned him around. Geneva (Ed. cast: Revolutionary Brochures, R. N. Baldwin, comp.) |

| 1881 | Tous socialistes | All Socialists | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1881 | L'Ordre | The order | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1881 | Les Minorités révolutionnaires | Revolutionary Minorities | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1881 | L'Organisation ouvrière | The Working Organization | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1882 | The Russian Revolutionary Party | The Russian Revolutionary Party | The Newcastle Chronicle/Fortnightly Review |

| 1882 | L'Expropriation | Expropriation | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1882 | La Guerre. | War | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1882 | Les Droits politiques | Political rights | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1882 | Théorie et pratique | Theory and practice | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1882 | L'Anniversaire du 18 mars | The anniversary of 18 March | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1882 | La Loi de l'autorité | Law of authority | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1882 | Le Gouvernement pendant la révolution | The government during the revolution | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1882 | Les Préludes de la révolution | The Preludes of Revolution | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1882 | The Situation in France | The situation in France | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1883 | Russian Prisons | Russian prisons | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1883 | The Fortress Prison of St Petersburg | St. Petersburg fortress prison | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1883 | Outcast Russia | Marginal Russia | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1884 | Exile in Siberia | Exile in Siberia | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1885 | Finland: a Rising Nationality | Finland: an emerging nationality | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1885 | Paroles d'un Révolté. | Words of a rebel | ed. Elisée Reclus. Paris; Flammarion. Montreal; Black Rose Books. New York (1992) |

| 1885 | What Geography Ought to Be | What the geography must be. | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1886 | The Place of Anarchism in Socialistic Evolution. | The Place of Anarchism in Socialist Evolution | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1886 | L'Expropriation | Expropriation | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1886 | Anarchy in Socialist Evolution | Anarchy in socialist evolution | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1886 | Comment on s'enrichit | As enriched | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1886 | La Pratique de l'expropriation | The practice of expropriation | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1886 | La Guerre sociale | The Social War | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1886 | Les Ateliers nationaux | National workshops | I turned him around. Geneva |

| 1887 | In Russian and French Prisons | Prisons | Ward and Downey. London |

| 1887 | The Coming Anarchy | The anarchy to come | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1887 | The Scientific Basis of Anarchy | The scientific bases of anarchy | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1888 | The Industrial Village of the Future | The industrial city of the future | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1888 | Le Salariat | The wager | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1889 | Le centenaire de la révolution | The centenary of the revolution | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1889 | Ce que c'est qu'une grève | What a strike is. | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1890 | Brain Work and Manual Work | Intellectual work and manual work | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1890 | La morale anarchiste au point de vue de sa réalisation pratique | Anarchist morality of the point of view of its practical realization | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1890 | Le Mouvement ouvrier en Angleterre | The Workers' Movement in England | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1890 | Le Premier Mai | The first of May | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1891 | La Morale anarchiste | Anarchist morality | Brochure. Paris |

| 1891 | Anarchist-Communism: Its Basis and Principles | Anarchist communism: its foundation and its principles | Brochure. London (Ed. cast: Revolutionary Brochures, R. N. Baldwin, comp.) |

| 1891 | Les Grèves anglaises | English strikes | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1891 | L'Entente | The Entente | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1891 | Étude sur la Révolution | Study on Revolution | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1891 | Message to delegates at the meeting of British and French Trade Unionists | Message to delegates at the meeting of British and French trade unionists | Freedom. London |

| 1891 | La Mort de la nouvelle Internationale | The Death of the New International | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1892 | La Conquête du Pain | The conquest of bread | Paris |

| 1892 | Affaire de Chambles | The Chambles affair | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1892 | Le Terrorisme | Terrorism | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1892 | Explication | Explanation | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1892 | The Spirit of Revolt | The Spirit of Rebellion | Commonweal |

| 1893 | On the Teaching of Physiography | About physiography teaching | Geographic Journal, vol. 2, p. 350-359. London |

| 1893 | L'agriculture | Agriculture | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1893 | Speech on Anarchism at Grafton Hall | Speech at Grafton Hill on Anarchism | Freedom |

| 1893 | Les Principes dans la révolution | The Principles of Revolution | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1893 | A Siècle d'attente | A century of waiting | Paris |

| 1894 | Les Temps nouveaux | New times | Paris |

| 1895 | The Commune of Paris | Paris commune | Freedom Pamphlets, no. 2, London: W. Reeves |

| 1895 | The Present Condition in Russia | Current conditions in Russia | The Nineteenth Century. V. 38, pp. 519-35. London |

| 1896 | L'anarchie: sa philosophie, are idéal. | Anarchism: its philosophy and its ideal | Libr. Sociale. Paris (Ed. cast: Revolutionary Brochures, R. N. Baldwin, comp.) |

| 1896 | L'Anarchie dans L'Evolution socialiste | Anarchy in socialist evolution | La Révolte. Paris |

| 1896 | An Appeal to the Young | Call for young people | W. Reeves. London |

| 1897 | La Grande Grève des Docks (with John Burns) | The big strike of the docks | Bibliothèque des Temps nouveaux. Paris |

| 1897 | L'Etat: son rôle historique | The state and its historical role | Les Temps Nouveaux. Paris (Hay ed. castellana) |

| 1897 | JSTOR The population of Russia | The population of Russia | The Geographical Journal, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 196-202. London |

| 1898 | JSTOR The old beds of the Amu-Daria | The ancient channels of Amu-Daria | The Geographical Journal, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 306-310. London |

| 1898 | Anarchist morality | Anarchist mortality | Free Society. San Francisco |

| 1898 | Some of the Resources of Canada | Some of Canada’s resources | The Nineteenth Century. March, pp. 494-514. London |

| 1899 | Cesarisme | Cesarism | Les Temps Nouveaux. Paris |

| 1899 | Fields, Factories and Workshops | Fields, factories and workshops | Hutchinson. London |

| 1899 | Memoirs of a Revolutionist | Memories of a Revolutionary | Houghton, Mifflin. New York |

| 1900 | Communisme et anarchie | Communism and Anarchy | Les Temps Nouveaux. Paris |

| 1901 | L'Organisation de la vindicte appellée Justice | The organization of revenge nicknamed Justice | Paris |

| 1901 | Modern Science and Anarchism | Modern science and anarchism | London. Ed in Russian; in English in 1903. (Ed. cast: Revolutionary Brochures, R. N. Baldwin, comp.) |

| 1901 | The Development of Trade Unionism | The Development of Trade Unionism | London |

| 1902 | Mutual Aid | Mutual support | Heinemann. London |

| 1902 | Revolving Zapiski | London | |

| 1903 | On Spherical Maps and Reliefs: Discussion. | Discussion with Mr. Mackinder; Mr. Ravenstein; Dr. Herbertson; Mr. Andrews; Cobden Sanderson and Elisée Reclus. | The Geographical Journal, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp. 294-299, JSTOR |

| 1904 | The desiccation of Eur-Asia | The drying of Eurasia | Geographical Journal, 23, 722-741 |

| 1904 | Baron Toll | The Toll Baron | The Geographical Journal, Vol. 23, No. 6, pp. 770-772, JSTOR |

| 1904 | The ethical needs of the present day | The ethical needs of the present | The Nineteenth Century LVI (330), pp. 207-26. London |

| 1904 | Comment fut fondé Le Révolté | How Le Révolté was founded | Les Temps Nouveaux. Paris |

| 1904 | Maxim Gorky | Maximum Gorki | The Independent, Vol. 57, No. 2924, pp. 1378-1371. New York; W. S. Benedict. |

| 1905 | Ideals and realities in Russian literature | Idales and Realities in Russian Literature | Boston: McClure, Philips and Co., 1919; New York: A. A. Knopf, 1915 |

| 1905 | The Constitutional Agitation in Russia | Constitutionalist agitation in Russia | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1905 | Bakunin | Jleb I volia | |

| 1905 | The Revolution in Russia | Revolution in Russia | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1906 | Nashe otnoshenie kret'ianskim i rabochim soiuzam | Jleb i volia. London | |

| 1909 | The Terror in Russia | Terror in Russia | Methuen. London |

| 1909 | The Great French Revolution, 1789-1793 | The Great French Revolution | London (Hay ed. castellana. Ed Projection, Buenos Aires, 1977) |

| 1910 | Anarchism | Anarchism | The Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th edition (Ed. cast: Revolutionary Brochures, R. N. Baldwin, comp.) |

| 1910 | Insurrection et révolution | Insurrection and revolution | Les Temps Nouveaux. Paris |

| 1913 | La Croisade la science de M. Bergson | The crusade in M. Bergson's science | Les Temps Nouveaux. Paris |

| 1913 | The Coming War | Next war | The Nineteenth Century. London |

| 1914 | L'action anarchiste dans la révolution | Anarchist action in the revolution | Paris |

| 1916 | La Nouvelle Internationale | The new International | Paris |

| 1916 | War! | War! | William Reeves. London |

| s/d | Law and authority; an anarchist essay | Law and authority; an anarchist essay | William Reeves. London |

| 1919 | Direct Action of Environment and Evolution | Direct action of the environment and evolution | The Nineteenth Century, V. 85, pp. 70-89. London |

| 1920 | The Wage System | The wage system | Freedom Pamphlets |

| 1921 | Ideal v revoliutsii | Ideal in the revolution | Byloe n°17 |

| 1922 | Etika | Ethics | Petrograd-Moscow; Truda Golos |

| 1923 | Chto delat'? | What to do? | Rabochii put'; no. 5. Berlin |

| 1924 | Ethics: Origin and Development | Ethics: its origin and evolution. | George G. Harrap & Co., Ltd. London |

List of publications

Various publications of the time published numerous articles and letters from Kropotkin. Among these are:

The Times, Nature, Daily Chronicle, The Nineteenth Century, Forthnightly Review, The Atlantic Monthly, La Revue Scientifique, The Geographical Journal, Freedom, Le Révolté , Temps Nouveaux, L'Avant Garde, Commonweal, Jleb i volia, L'Intransigeant, Litski Jleb i volia, Voice of Labour, Newcastle Daily News, Arbeiterfreund , Land and Freedom, Bataille Syndicaliste, The Speaker, Le Soir and Ecole Renouvé (Brussels), The Protest, Probuzhdenie (Detroit), Golos Truda, Dielo Truda and Independent (New York), Politiken (Copenhagen), The Alarm, El Productor (Barcelona), Avant Courier (Oregon), La Revista Blanca (Madrid).

Bibliography about Pyotr Kropotkin

- Alpharo Blanco Àlex (2012) Concepts of the ethics of Kropotkin Aldarull Edicions Barcelona ISBN 978-84-938538-9-1

- Berneri, Camillo. (1943). Peter Kropotkin, his federalist ideas. London; Freedom Press.

- Borovi, A. A. (ed.) (1923). Dnevnik P. A. Kropótkina. Moscow-Petrograd: Gosizdat.

- Breitbart, Myrna Margulies (1981). "Petr Kropotkin, The Anarchist Geographer." Geographay, Ideology and Social Concern. D. R. Stoddart (ed). Totowa, NJ: Barnes and Noble Books, pp. 134-153.

- Breitbart, Myrna (1981). Geography, Ideology and Social Concern. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Cahm, C. (1989). Kropotkin and the Rise of Revolutionary Anarchism 1872-1886. Cambridge; Cambridge University Press.

- Cleaver, H. (1994). "Kropotkin, Self-valorization and the Crisis of Marxism." Anarchist Studies. Vol. 2, Number 2. pp. 119-136.

- Cappelletti, Angel. Kropotkin's Thought: Science, Ethics and AnarchyMadrid, Zero, 1978.

- Diaz, Carlos. Three biographies: Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin. Journals for Dialogue, 1973 ISBN 84-229-7038-4, 9788422970385

- Dugger, W.M. (1984). "Veblen and Kropotkin on Human Evolution," Journal of Economic Issues, XVIII, pp. 971-85.

- Ferretti, F. (2010). “The correspondence between Elisée Reclus and Pëtr Kropotkin as a source for the history of geography”, Journal of Historical Geography.

- Galois, B. (1976). "Ideology and the idea of Nature: The Case of Peter Kropotkin." Antipode. V. 8, pp. 1-16.

- Girdner, E. (1992). review: Kropotkin and the Rise of Revolutionary Anarchism 1872-1886 by Caroline Cahm. Social Anarchism. No. 17, pp. 60-64.

- Alvaro Girón. "Kropotkin between Lamarck and Darwin: the impossible synthesis", Asclepio-Vol. LV-1-2003.

- Alvaro Girón. “Introduction”, in P. Kropotkin, The Natural Selection and Mutual Support, Madrid, 2009.

- Gonzalez-Blanco, Edmundo. The Anarchism Exposed by Kropotkin, General Library and Graphic Arts Agency, 1931.

- Goodman, Paul. "Kropotkin at this moment." Dissent Nov-Dec. 1968, p.519-522.

- Gould, S.J. (1988). "Kropotkin was no Crackpot." Natural History, v97. pp. 12-21.

- Harney, Stefano (2002). "Fragment on Kropotkin and Giuliani." Social Text. v. 20, n. 3, pp. 9-20.

- Holloway, W. (1942). "What Kropotkin means to me." Centennial Expressions, pp. 34-35. New York.

- Ishill, Joseph, editor (1924). [3] Peter Kropotkin: the Rebel, Thinker and Humanitarian. Berkeley Heights, N.J.; Free Spirit Press.

- Ivanova, T.K., Markin, V.A. (2008). “Pëtr Aleksejevic Kropotkin and his monograph Researches on the Glacial Period (1876)”, London Geological Society, Special Publications 301, pp. 117-128.

- Kearns, Gerry (2004). "The political pivot of geography." The Geographical JournalVol. 170, No. 4, December, pp. 337-346.

- Keltie, J. S. (1921). "Obituarry for Peter Alexeivich Kropotkin." The Geographical Journal. V. 57, pp. 316-9.

- Knowles, Rob (2003). "Kropotkin And Reclus: Geographers, Evolution, and 'Mutual Aid'," in John Laurent (ed.) Evolutionary Economics and Human NatureAldershot, Edward Elgar.

- Maíz, Jordi (coord.) (2021). Kropotkin. One hundred years later. Madrid: Fundación de Estudios Libertarios Anselmo Lorenzo. 408 pp. ISBN = 978-84-123507-1-5

- McCulloch, Caroline (1984). "The Problem of Fellowship in Communitarian Theory: William Morris and Peter Kropotkin." Political Studies. XXXII, pp. 437-450.

- Metcalf, Wm. (1987). "Anarchy and bureaucracy within the alternative lifestyle movement: or Weber vs Kropotkin at Nimbin."Social Alternatives. V.6, No.4. November 1987: 47-51.

- Miller, M.A. (1976), Kropotkin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Miller, D. (1983). "Kropotkin." Government and Opposition. 18, pp. 319-38.

- Morris, Brian (2002). "Kropotkin's Ethical Naturalism." Democracy " Nature ". Vol. 8, No. 3, 423-437.

- Morris, Brian. Kropotkin: the Politics of Community, Humanity Press, 2004.

- Morris, Brian. The Anarchist Geographer: an Introduction to the Life of Peter KropotkinGenge Press, 200.

- Morris, Brian. Basic Kropotkin: Kropotkin and the History of Anarchism, Anarchist Communist Editions pamphlet no.17. The Anarchist Federation, October 2008.

- Muiña, Ana. Kropotkin, the bright winter sun, Introduction to "Russian literature, ideals and reality". Piotr Kropotkin. Madrid. The deaf flashlight. 2014.

- Osofsky, S. (1979). Peter Kropotkin. Boston: Twayne Publishers.

- Padovian, Dario (1999). "Social Morals and Ethics of Nature: From Peter Kropotkin to Murray Bookchin." Democracy " Nature ". Vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 485-500.

- Perry, Richard J. Radcliffe-Brown and Kropotkin: the heritage of anarchism in British Social Anthropology. Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers 51/52 (1974), 61-65.

- Robinson, V. (1908). Comrade Kropotkin. New York.

- Stoddart, D. R. (1976). "Kropotkin, Reclus, and 'relevant' geography." Bulletin of Environmental Education. V. 58, p. 21.

- Smith, M. (1989). "Kropotkin and technical education: an anarchist voice." in For Anarchism: History, Theory, and PracticeGoodway D., ed. London and New York; Routledge. pp. 217-234.